|

National Park Service

Administrative History: Expansion of the National Park Service in the 1930s |

|

|

Chapter Six: The National Park Service, 1933-1939 Introduction For Arno Cammerer, something of the scope of the increased responsibilities that had devolved upon his agency on August 10, 1933, became clear in a letter of Frank T. Gartside, acting superintendent of the National Capital Parks. Responding to a verbal request, Gartside listed the duties which had formerly belonged to the Director of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital that were transferred to Cammerer's new office:

The increased responsibilities that accrued to his office as a result of reorganization, involvement in emergency programs, and new initiatives in history and recreation exacted a heavy price from Arno Cammerer. As early as 1935 his friends were beginning to worry about him. "You must conserve yourself Cam," Horace Albright wrote on July 14, "Should you lose your health, they will take your job and that will be the end of the Mather group in National Park Service activity." [2] When he resigned in 1940, Cammerer wrote that while he had made an excellent recovery from a "complete [physical] collapse!" he had suffered the previous year, he was not able to withstand the continued strain of his office. [3] Within a year, Cammerer, who accepted the position of Regional Director, Region I, following his resignation as director, was dead, the victim of a second coronary. The new responsibilities that devolved on the director's office with the transfer of the office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the National Capital were a reflection of the new responsibilities that came to his agency in the reorganization of 1933. These new responsibilities, moreover, multiplied with the growing involvement in New Deal recovery efforts and the new initiatives in history and recreation. Park Service administrators faced a dual problem after 1933. They had to cope with new, and often unfamiliar, issues raised by the new programs. At the same time, they had to find a way to reconcile traditional values and principles with an agency that was suddenly much larger and complex. The way in which they approached both brought about significant changes in the organizational framework of their agency. It provides a case study of the federal bureaucracy during the New Deal. A. Growth of the National Park Service The Roosevelt administration quite obviously hoped that reorganization of the executive branch would result in a savings to the government through a reduction of personnel. By early October 1933, however, it was becoming evident that as far as administration of the parks was concerned, that goal would not be easily reached. On October 3, Arno Cammerer wrote that the Director of the Bureau of the Budget had expressed "extreme disappointment" that consolidation and reorganization of the various parks and monuments had resulted in the elimination of only 97 of 4,055 positions. [4] Cammerer, whose title was now Director of the Office of National Parks, Buildings, and Reservations, continued that the "old National Park Service" had been able to make a further reduction by eliminating all positions that were unfilled because of a reduction in appropriations, and called upon the heads of other offices in his agency to make similar efforts. [5] Any reduction in the agency's personnel would soon prove transitory, however. Just two years later, Cammerer reported that "supervision of work under the emergency programs resulted in a heavy strain on all park supervisory personnel, both in the Washington office and the field." [6] The growth of the Service that resulted from the reorganization of 1933, participation in New Deal emergency programs, and new initiatives in history and recreation was so great that many Park Service employees feared that the character of the Service itself would be irretrievably lost. [7] Before the reorganization of 1933, the National Park Service was a small, tightly-knit organization whose members often referred to themselves as the "Mather Family." Although there is considerable discrepancy in the sources regarding the exact number of personnel, the most complete records available indicate that some 700 permanent and 373 temporary employees were on the rolls on October 1933, the date Executive Order 6166 became effective. [8] The Washington office and various field offices of that office employed 147 people (142 and 5 temporary). Four hundred and seventy-six permanent and 331 temporary employees were located in the National Parks and 51 more were assigned to the national monuments (thirty-seven permanent and ten temporary). [9] The immediate impact of Executive Order 6166, in terms of size, was the increase of 4,209 employees into what was to become known as the Office of National Parks, Buildings, and Reservations. [10] The largest number of new employees was the 3,047 permanent and 304 temporary appointees of the Buildings Branch. A total of 629 people were employed in the National Capital Parks and 139 more were assigned to the various sites transferred from the War and Agriculture departments:

Two years later, on November 30, 1935, the number of employees had more than doubled to 13,361. Of those categories listed on the August 10, 1933, report, the Branch of Buildings showed the largest increase--from 3,441 to 4,220. [12] The number of people engaged in what would be considered to be more traditional Park Service activities than building maintenance--and that is taken to include employees at areas formerly administered by the War and Agriculture departments--actually declined from 1,840 to 1,625. The latter figure, which includes both permanent and temporary employees, most probably reflects the normal reduction in temporary personnel in the national parks following the end of the travel season. The large increase in personnel in the agency between 1933 and 1935 was a reflection, actually, of the Service's growing importance in the New Deal recovery programs. More than half of the employees on the roles on November 1935--7,480--were engaged directly in recovery programs. They were paid, moreover, out of emergency, not regular appropriations. [13] According to Director Cammerer, the number of employees reached a peak of 13,900 in 1937. [14] By 1939, however, reflecting both the transfer of responsibility for maintenance of public buildings and winding down of emergency programs, the number of employees dropped to 6,612. Some 2,976 employees were still involved in administrative and supervisory capacities in the CCC. The number of people assigned to all National Park Service offices was 3,636. This represented a three-fold increase in 15 six years. [15] Not only did the number of employees of the National Park Service increase dramatically after 1933, but it is also possible to discern more clearly the increasing specialization, or professionalization of the Service during that time. Clearly, professionalization of the National Park Service cannot be traced solely to the 1930s, as both Mather and Albright had strived to that end. But while professionals of one kind or another may have always been a part of the make-up of the Service, the movement toward professionalization certainly gained a new impetus during that decade. [16] The growth of professions that came after 1933 was, in large part, the product of a combination of New Deal recovery efforts and the entry of the National Park Service into the field of historic preservation. The depression created a large pool of unemployed historians, archeologists, architects, and museum curators. The new National Park Service initiatives in history, along with what seemed like unlimited funds, allowed people like Verne Chatelain and Charles Peterson to create programs that provided such jobs. "From 1933 onward," observes Charles B. Hosmer, "the National Park Service was the principal employer of the professionals who dedicated their careers to historic preservation." [17] Most of these professionals began their work as temporary historical foremen or historical technicians in the CCC. Later they found permanent Civil Service jobs with the National Park Service. Some of them would, in time, come to occupy positions of authority in the Service. [18] In 1931, for example, there were only two historians, as such, in the National Park Service. [19] In June 1933, Dr. Chatelain hired graduate students from the University of Minnesota to be historical foremen in the CCC camps. [20] Just two years later, one of these young historians,Ronald F. Lee, was Historian for the State Park Division of the National Park Service. Lee's description of his job indicates something of the growth of the Service's history program and impact on the history profession:

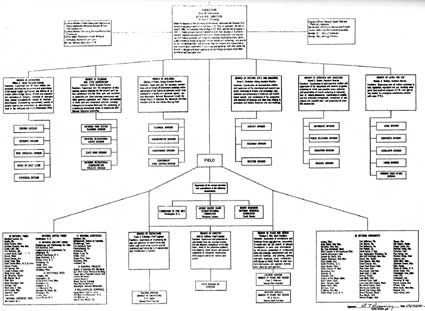

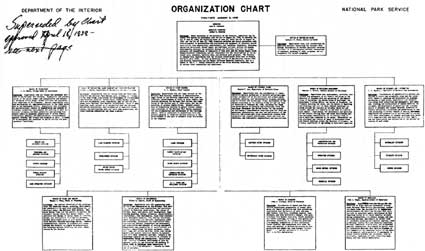

The growth of the historical profession in the Service is only an example of the growth of specialization after 1933. With the development of the Historic American Buildings Survey and the dramatic increase in museums in the system, other examples would be as dramatic. B. Reorganization--The Washington Office In 1930, after he became director, Horace Albright instituted the first major reorganization of the National Park Service. [22] The new organizational structure reflected Albright's stated intention to depersonalize decision making at the director's level, and to provide for the delegation of authority in a way that Stephen Mather had never been able to do. [23] In 1931 the new organization, which is shown below, consisted of the director's office and four major branches at the Washington level. Each branch was headed by an assistant director. Arthur E. Demaray's Branch of Operations was responsible for all fiscal and personnel functions. Demaray exercised supervision over the Chief Clerks Division and Auditors of Park Operator's Accounts Division. [24] Assistant Director George A. Moskey's Branch of Use, Law, and Regulation oversaw all matters relating to legislation, contracts, permits, development of the system, etc. [25] Conrad L. Wirth's Branch of Lands was charged with responsibility over all land matters, except those relating to the law. [26] Dr. Harold Bryant, as head of Research and Education, supervised and coordinated all educational (interpretation) and research matters in the Service. Isabelle F. Story, as chief of the Division of Public Relations and Ansel Hall, Chief of the Field Division of Education and Forestry, reported directly to Dr. Bryant. [27] Rounding out the organization were the field offices, all of which reported to the director: superintendents of the national parks, superintendents of national monuments, custodians of national monuments, Engineering Division, and Landscape Architectural Division. [28]

The additional responsibilities that came to the Service through the reorganization of 1933, involvement in recovery programs, new initiatives in history and recreation all resulted in changes in the structure of the organization. By 1939 the organization was considerably more complex, little resembling the one described above. Transfer of the Office of Public Buildings and Public Parks of the nation's capital under Executive Order 6166, for example, necessitated the creation of a Branch of Public Buildings, with a Division of Space Control. [29] By December 1934, additionally, a new Branch of Forestry, which was actually pulled out of Ansel Hall's old field division of Education and Forestry, supervised emergency activities. [30] Conrad Wirth's Branch of Planning had been expanded to include a Division of Investigation of Proposed Parks and Monuments; Maps, Plans and Drafting Division; The State Park Division (ECW program); Submarginal Land Division; and The National Recreation Survey Division. [31] Other indications of the expanded program of the Service were a Parkway Right-of-Way Division in Moskey's Branch of Lands and Use and Historical Naturalist and Wildlife Division in Dr. Bryant's Branch of Research and Education. [32] Finally, Branches of Engineering and Plans and Design each had an Eastern Division and Plans and Design had a Western Division as well. [33] Passage of the Historic Sites Act in August 1935 led to the creation of a new Branch of Historic Sites and Buildings under the supervision of Acting Assistant Director Verne E. Chatelain. [34] The functions of the new branch, which had Eastern and Western divisions as well as a research division were

At the same time, the Branch of Planning became the Branch of Planning and State Cooperation. The functions of this expanded branch were the supervision over the compilation of data covering advance planning for the National Park System, "coordination with the State Park and Recreational Authorities and State Planning Commissions and other agencies; supervision over Federal participation in State park and recreational activities; and the conducting of a continuing recreational survey in cooperation with the National Resources Committee." [36]

By the end of the decade, as reflected in the organization charts of the Washington office, the National Park Service was a much larger and a considerably more complex organization than it had been in 1933. [37] There were now ten branches instead of four: Operations (J. R. White, Acting); Recreation and Land Planning (Conrad L. Wirth); Office of Chief Counsel (G. A. Moskey); Historic Sites (Ronald F. Lee); Buildings Management (Charles A. Peters); Research and Information (Carl F. Russell); Plans and Design (Thomas C. Vint); Branch of Engineering (Oliver G. Taylor); Forestry (John D. Coffman); and Memorials (John L. Nagle). [38] Not only were there more branches, but the functions had increased in scope and complexity. In 1933, for example, the function of the Branch of Operations was

In 1939, the board included five divisions--Budget and Accounts, Personnel and Records, Safety, Public Utility Division, and Park Operations. [40] The functions of the enlarged branch were:

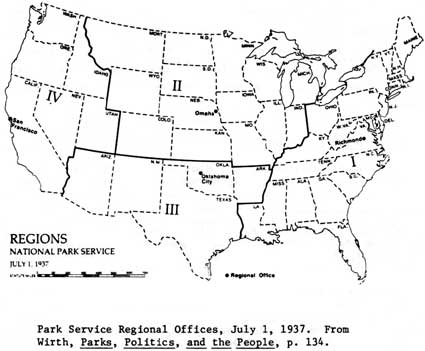

C. Regionalization None of the organizational changes made in response to the expansion of the park system in the 1930s would have greater long-term ramifications for administration of the Park Service than the establishment of regional offices in 1937. The creation of a new level of administration between the Washington office and the field was not, it must be made clear, a new idea. Park Service officials long had been concerned over the difficulty of effectively supervising and coordinating a widely-scattered system of parks and monuments from Washington, D.C. [41] During the 1920s the Service had established field offices in Yellowstone National Park, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Denver, Portland, and Berkeley. [42] These offices performed specific functions--landscape architecture, sanitation, engineering, and education (interpretation) for example--and did not exercise any general administrative or supervisory control over parks and monuments. A more immediate example of regionalization was the system developed to administer the Civilian Conservation Corps described on pages 77-96. In fact, because such a large number of NPS employees were involved directly in ECW, Director Cammerer stated in 1936 that the Service was already 70 percent regionalized. [43] At a 1934 park superintendent's conference, held while preliminary discussions regarding regionalization were underway in the Washington office, it became clear that many people in the field as well as in the Washington office believed that the problem of communication was becoming critical as the Park System expanded. Reacting to a suggestion that the Park Service adopt a regional system roughly similar to that already employed by the Forest Service, Frank Pinkley, Superintendent of the Southwest Monuments, indicated that he had become increasingly concerned with the separation between the Washington office and the field, and that of "at least twenty different superintendents" with whom he had discussed the matter, all were of the same opinion. [44] Speaking for superintendents of the new historical areas, B. Floyd Flickinger of Colonial seconded Pinkley's observations, and indicated that he believed that the greater coordination that would come from regionalization was especially critical for the historical areas. [45] None of the superintendents spoke out against regionalization at the conference Yet, while those superintendents from cultural areas were enthusiastic over the possibility of regionalization of the Service, many of the superintendents from the natural areas were less so. While agreeing that "anyone in the field for years past must have realized we would have to come to some form of regionalization," John R. White of Sequoia National Park cautioned:

Actually, White continued, a more economical solution to the problem of communication than regionalization might be simply to have the superintendents travel to Washington more often. [47] The plan advanced before the superintendents in 1934 would have established as many as five regions determined by classification of areas. Two regions would have incorporated cultural areas--one the Southwestern monuments, the other the military parks and monuments. [48] The scenic parks and monuments would have been divided among as many as three regions. [49] The chief executive for each region would be responsible for overseeing that the policies and principles enunciated by the Washington office were implemented by field personnel. To facilitate communication between the Washington office and regions, one of the regional directors would be required to be in Washington at all times. [50] Because of funding problems, it was believed that at least for the short run, the regional director would be a "qualified superintendent." Seemingly, the superintendent who served as regional director would not be relieved of his duties in the park. Little was done, apparently, to follow up the discussions held in 1934. It was not until January 26, 1936, that Director Cammerer appointed a committee headed by Assistant Director Hillory A. Tolson to study the question of regionalization and submit a plan. [51] In mid-February, the committee forwarded to Cammerer a plan of "a simple organization that can be manned and administered from trained personnel and money now available." [52] The regional system proposed would, the committee said, bring the director and his assistants back into a more intimate touch with the field. It would allow greater supervision of the field, while preserving the autonomy and individuality of the parks. Administrative decisions could be made in the field rather than in Washington, and because the proposal would strengthen the influence of professional branches, those decisions would be based on the best technical advice. The system would, finally, provide greater channels of promotion from park to park, parks to region, and regions to Washington. Because promotion opportunities would occur in the various branches, an individual could advance within his profession, and not be necessarily diverted into administration [53]. The memorandum discussed above did not spell out the make-up of regions. That came several days later. The proposed system was based on a combination of unit classification and geography similar to that suggested to the superintendents in 1934. [54] Region 1, with Chief Historian Verne E. Chatelain as the recommended regional director, would include all historical and military parks, monuments, battlefield sites, and miscellaneous memorials east of the Mississippi River. [55] Region 2, the second region established primarily on a classification of areas would have been headed by Frank Pinkley, Superintendent of the Southwestern monuments. Pinkley's region would have included the southwestern monuments as well as Mesa Verde and Carlsbad Cavern national parks, and Petrified Forest, Wheeler, and Great Sand Dunes national monuments. The remaining three regions would have been headed by superintendents of large natural parks--C.G. Thompson of Yosemite (No. 3), Superintendent O.A. Tomlinson of Mount Rainier (No. 4), and Roger Toll of Yellowstone (No. 5). [56] The primary division was geographical and the regions would have included both natural and cultural areas:

It was believed that eight existing and projected parks--Acadia, Great Smoky Mountains, Platt, Hot Springs, Isle Royale (projected), Mammoth Cave (projected), and Everglades (projected) could function as they did for the present, although it was recommended that when Mammoth Cave and Everglades were established they would be coupled with Great Smoky Mountains, Platt, and Hot Springs into Region 6. On March 14, Acting Director Arthur Demaray, forwarded a memorandum that described in detail the responsibilities of the proposed regional offices. Duties and responsibilities would certainly change over time, he said, but the following were representative of the work that it was proposed to transfer:

The Service would go slowly with regionalization, Demaray concluded, and would enlarge the authority of the regional directors only when such action was justified by experience. [59] Secretary Ickes answered Cammerer's request on March 25. Reflecting his well-known antipathy for bureaucracies, Ickes wrote that he was reluctant to agree to the creation of offices outside Washington "because it would be only a question of time until a bureaucratic field force would become established to the detriment of the Washington office." While he recognized that Washington officials had to be "fully informed of administrative problems and actions," he did not believe that creation of regional offices would contribute to that end. [60] Rather, he believed that the appointment of district supervisors in the Washington office would be more effective, and instructed Cammerer to revise the proposal accordingly. Ickes was not the only one to express reservations regarding regionalization. A flurry of letters to the secretary, which Cammerer believed was inspired by the National Parks Association, all indicated a concern that the grouping of historical and natural areas would be to the detriment of the latter. [61] Within the Service many "old-line superintendents object to the concept as an unwarranted intrusion on their ability to communicate directly with the Washington Office, and many rank and file personnel saw it as a barrier to career advancement." [62] Director Cammerer believed that much of the opposition to regionalization from both groups would be dissipated by appointing "old-time" Park Service men to head the various regions. [63] While opposition to regionalization did not immediately disappear, Cammerer and his deputies were able to blunt the efforts of it, and convince Secretary Ickes. On January 21, 1937, more than two years since regionalization was first discussed at the Annual Superintendent's Conference, Secretary Ickes initialed his approval of a regional system that would be implemented after the end of the fiscal year. [64] Accordingly, on August 7, 1937, Director Cammerer issued a memorandum that implemented regionalization of the National Park Service. The plan approved by Secretary Ickes established four geographic regions:

Interestingly, of the first four regional directors only one, Thomas Allen, Jr. (Region II), had been a superintendent of a natural park, although Carl P. Russell (Region I) and Frank Kitteridge (Region IV) had considerable National Park Service experience. [66] Herbert Maier, who was named acting director of Region III, had been in charge of the Service's CCC and emergency activities of Region III (CCC). In addition, the associate regional director would be the current CCC regional officer. [67] The implementing memorandum made it clear that the Washington office intended to proceed cautiously with regionalization, and subsequent memorandums issued throughout the rest of the decade amplified, refined, or in some cases altered functions of the regional offices. [68] Nevertheless, the outlines of the organization that would administer the National Park Service in the future were drawn, and it reflected Secretary Ickes concern that the field offices not rival the Washington office:

Establishment of regional administrative units was an experiment. Within a short time it proved its effectiveness to both Washington officials and field personnel. In his annual report of 1938, Director Cammerer wrote:

The following year, while calling for establishment of one additional region, the park superintendents resolved:

D. Retrospect Park Service officials grappled in the 1930s with a whole range of issues that rose from a great expansion of the park system, new and unfamiliar programs, and a massive infusion of emergency funds. Coincidentally, they faced the problem of maintaining traditional values and principles in an organization that was suddenly both larger and more complex. As they did so, they found themselves subject to considerable criticism, some of it from unaccustomed sources. On one hand, Park Service administrators were criticized for the perceived failure to properly integrate the new historical areas into the Park System. Many of the strongest critics were those within the Service who were involved in the new areas. Edward A. Hummel, who came into the Service as an assistant historian doing ECW work in the Omaha office, remembered that the historical areas remained the "step-children" of the Service throughout the decade. The reason for this, he said, was that administrators simply had no interest in those areas. Indeed, he concluded, the National Park Service was two separate organizations in the 1930s. [72] Roy E. Appleman, another historian who came into the Service under the ECW program in the 1930s, wrote that while the system generally worked well during that decade, the background of NPS administrators (forestry, "ranger-type," etc.) prevented them from recognizing that new and different policies and procedures were needed for the historical areas. [73] Historians were not the only ones concerned. In 1940 Regional Director (Region I) Minor R. Tillotson, a man whose Park Service background was in the natural parks in the West, agreed. Speaking before the Historical Technicians Conference in 1940, Tillotson stated his opinion that "the National Park Service has thus far, to a great degree, failed in its task relating to the historic areas under its administration, not so much in their selection and development as in the interpretation of them to the public." [74] While historians and others argued that the Service did not adequately integrate the new areas into the system, others, and many old friends of the Park Service were among them, charged that the Service had strayed too far from its traditional course. Even in the days of Stephen Mather the Park Service had suffered criticism from those who believed that the National Parks should consist of great unspoiled temples of beauty. By the mid-1930s these "purists," as Donald Swain calls them, were in full cry against what they considered to be excessive construction and development in the parks, an over-zealous concern for tourism and the increases that it brought, and the heightened concern for recreation. [75] Most important, however, was what these critics considered to be a shift of interest from protecting the great scenic areas in the West. In February 1936, for example, Robert Sterling Yard, editor of The National Parks Bulletin, published an article entitled "Losing Our Primeval System in Vast Expansion." [76] While the general tone of Yard's article was less strident than was the title, he nevertheless wrote that the expansion of the system and new directions taken by the National Park Service had ended the long intimate relationship between the National Park Service that existed in "upbuilding of the primitive system and defense of standards." The next year, James A. Foote, representing the National Audubon Society, published an open letter to Secretary Ickes in which he charged that:

In 1936, four staunch friends of the National Park Service--the Sierra Club, Wilderness Society, National Parks Association, and Audubon Society--united in calling for a reorganization that would create a "National Primeval Park System":

Park Service officials were sensitive to these criticisms, particularly to those of their erstwhile friends. Again and again, from the mid-thirties onward, they stepped forward to defend themselves. George Wright, NPS Chief of Planning, for example, denied in a speech before the Council Meeting of the American Planning and Civic Association that the expansion of the system had resulted in lowered standards:

"Let the friends of our national parks leave it to the National Park Service to safeguard itself against intrusion of trash areas," he concluded, and "devote their energies instead to completing the park system while there is still time to do it." Speaking before the same group at a later date, Associate Director Arthur E. Demaray addressed the issue of overdevelopment in the parks. Demaray admitted that the park administrators faced "tough problems" as they made the parks available for the use of the people while at the same time carrying out Congress' mandate "that they leave the parks 'unimpaired for the benefit of future generations."' An examination of the record, he argued, would show that the Service had succeeded, and that through "greater efficiency in planning, construction, and administration, the facilities and accommodations provided have been implements of conservation, and that nature is actually less disturbed in the parks today than it was in 1917." "In the face of widespread misunderstanding and criticism," he concluded, the National Park Service remained "one of the most forceful and honest agencies of conservation in the Federal Government." [80] Actually, however, Park Service officials need not have been so defensive about their actions in the 1930s. For, despite surface appearances, the inclusion of War and Agriculture department areas in 1933, development and construction in the parks under the emergency programs, the publicity campaigns and increased tourism that it brought, and growth of historic preservation programs did not represent a break with past traditions as many thought. Rather, save for the duties involved in building maintenance, what happened to the National Park Service in the 1930s was a logical extension of the traditions established by Stephen Mather and Horace Albright. In fact the directorship of Arno Cammerer, who was replaced by the first man who did not serve under Stephen Mather, was a culmination of that earlier tradition. [81] The 1930s, then, witnessed the full bloom of policies established earlier. As such it had been the most exciting and creative in the Service's history. By the end of the decade Service officials were ready to retrench. Part of this had to do with outside events--the winding down of emergency programs and steadily declining funds and outbreak of war in Europe which drew attention elsewhere. Beyond events, however, was a general feeling among Park Service officials that it was time to pull back, to consolidate gains and to become, as former director Albright indicated, a land administration bureau, whose focus was on the national parks. [82] The declaration of war in December 1941 certainly brought the period to an end. The effort to deal with issues raised in the 1930s would have to wait. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

unrau-williss/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 29-Feb-2016