100 Years of Federal Forestry

Agriculture Information Bulletin No. 402

|

|

|

|

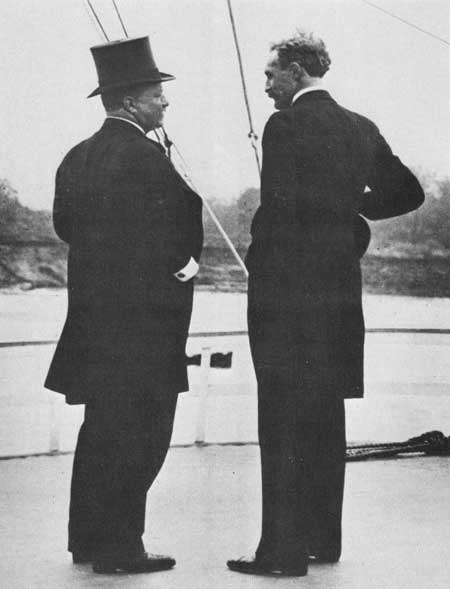

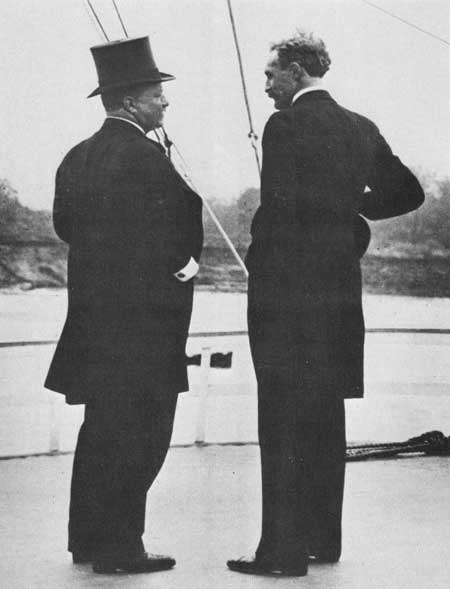

President Theodore Roosevelt and Chief Forester Gifford

Pinchot on the river steamer MISSISSIPPI. They made this trip

with the Inland Waterways Commission down the Mississippi River

in October 1907, to awaken interest in the development of our

inland waterways. (F—523656)

|

"Forestry is the preservation

of forests by wise use . . . forestry means making the forests useful

not only to the Settler, the rancher, the miner, the men who live in the

neighborhood, but indirectly to the men who may live hundreds of miles

off down the course of some great river which has had its rise among the

forest bearing mountains."

President Theodore Roosevelt

The Early Years Of The Forest Service, 1905-1916

Highlights

The early years of the Forest Service were a period

of pioneering in practical field forestry in the United States.

"Conservation" began to be practiced and the term became widely known.

Webster defines conservation "especially" as "planned management of a

natural resource to prevent exploitation, destruction, or neglect."

Broad popular support of resource conservation encouraged dramatic

forestry progress in the early years, stimulated by Pinchot and his

small but able and dedicated staff. The close warm relationship and

respect between President Theodore Roosevelt and the Nation's Chief

Forester Gifford Pinchot fostered the development of resource

conservation. Congress helped by passing favorable legislation.

A new era in forestry began in 1905 as Congress

transferred the Forest Reserves from the Department of the Interior to

the Department of Agriculture. The Bureau of Forestry became known as

the Forest Service, the first of many Federal agencies to adopt the

designation of "Service." two years later, to emphasize that the forests

were for use, the name Forest Reserve was changed to National Forest.

Administration was decentralized to take maximum advantage of local

judgment.

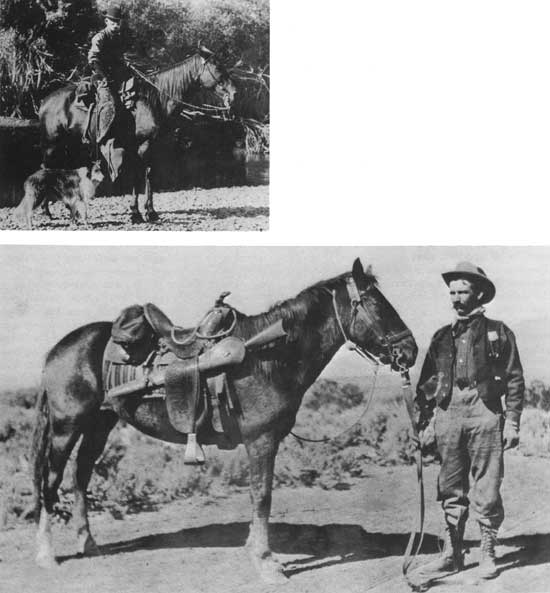

The early day forest rangers, riding horseback over

mountain trails, were essentially custodians of the forests, protecting

them against fire, game poachers, timber and grazing trespassers, and

exploiters.

To provide use of the public forests, rangers issued

permits for grazing of domestic livestock and made the first sales of

mature timber and other forest products. As money came in, Congress

decreed that part of the receipts should go to the States for schools

and roads in the counties where the grazing and cutting took place.

Other receipts were set aside for roads and trails within the National

Forests.

Research, essential to progress in any field,

received more attention as new field locations became available. The

first forest experiment station was established in Arizona in 1908, soon

to be followed by other research units in Colorado, Idaho, Washington,

California, and Utah. In 1910, the Forest Service established the Forest

Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin, in cooperation with the State

University. It was to become world famous for its scientific study and

development of wood products and their uses.

Cooperation with State forestry departments in fire

protection was established by law in 1911. This was the forerunner of

what were to become longtime relationships and cooperative efforts

between the Forest Service and State foresters, the third principal part

of the Forest Service entity, alongside National Forest administration

and research.

The Weeks Act of 1911 authorized the purchase, as

National Forests, of private lands—cutover, burned over, and farmed

out—mostly east of the Great Plains, where there was little public

domain left. (National Forests in Alabama, Arkansas, Michigan,

Minnesota, and Florida had their origin as public domain areas, but

additions were made by purchase.) The first National Forest to be

created from private lands was the Pisgah in the mountains of North

Carolina. Its nucleus was the Biltmore Forest, once managed by Pinchot,

and site of a forestry school since 1898.

1905-1916

|

|

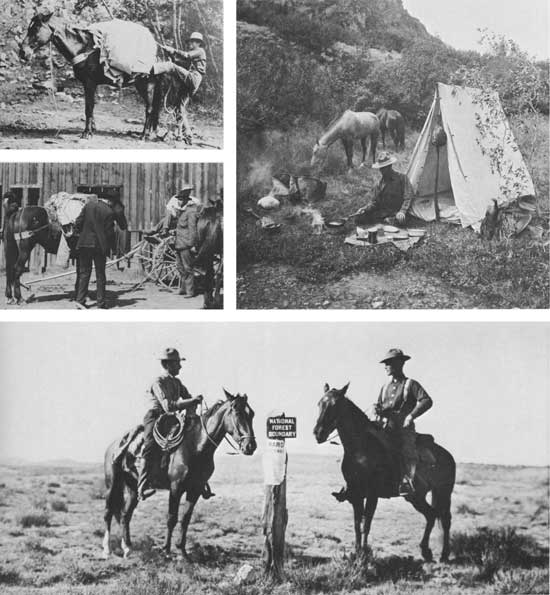

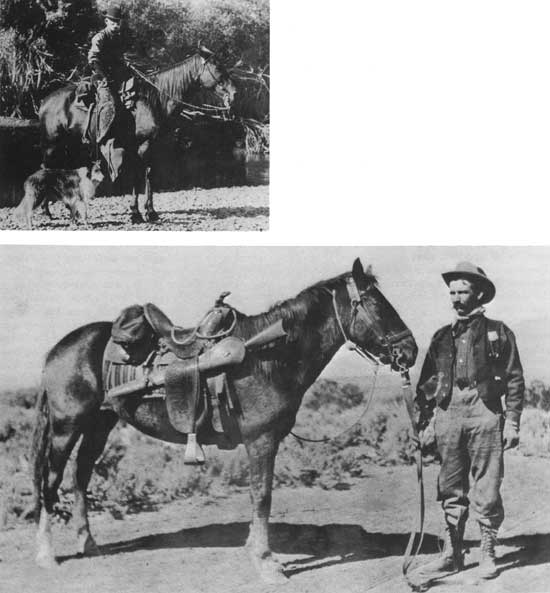

The early forest rangers and forest supervisors were outdoorsmen,

used to trail life, many of the former cowboys, trappers, and

woodsmen. As pioneer custodians of the forest resources, they

showed loyalty and devotion to public service that have endured

through the years. Their principal job was to keep the newly

created Forest Service free from fire, poachers, and timer and

ranger trespassers. 1 (top). Forest Ranger J. C. Wells, Stanislaus

Forest Reserve (now National Forest), California, in 1905. (F—33283) 2 (bottom).

Forest Ranger Jim Sizer, Apache National Forest, Arizona, in about 1910. (F—460531)

|

|

|

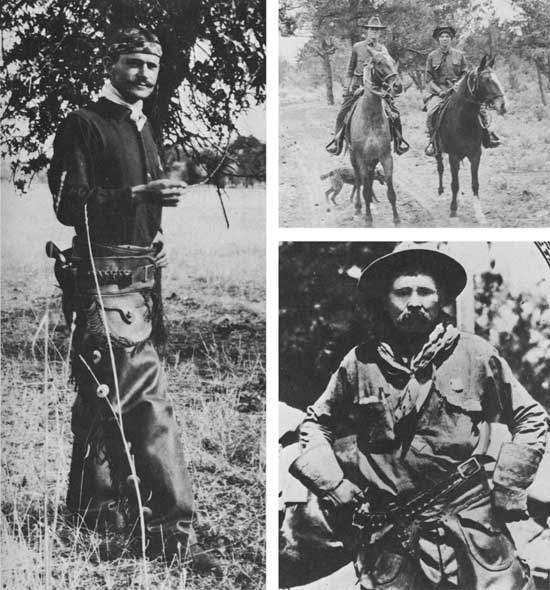

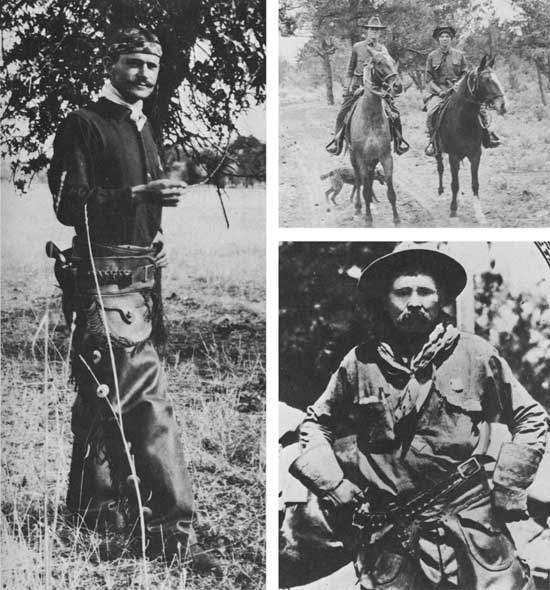

1 (left). Forest Supervisor Harold Greene rode with his wife in

the Tusayan (now Kaibab) National Forest, Arizona, in April 1914. (Harold Greene)

2 (top right). Forest Assistant W. H. B. Kent, Huachuca Forest

Reserve (now Coronado National Forest), Arizona, in 1905. (F—422214)

3 (bottom right). Forest Ranger "Fritz" Sethe, Columbia (now

Gifford Pinchot) National Forest, Washington, in 190. (F—514641)

|

|

|

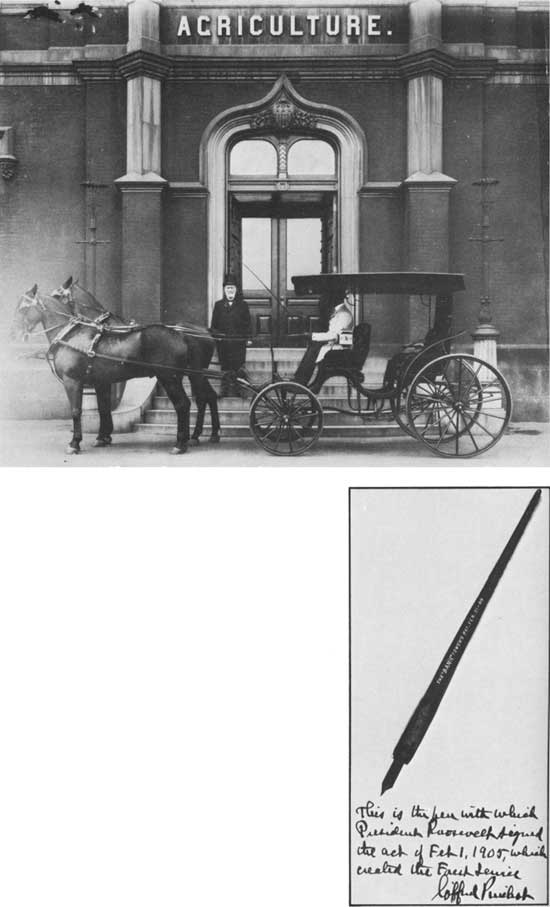

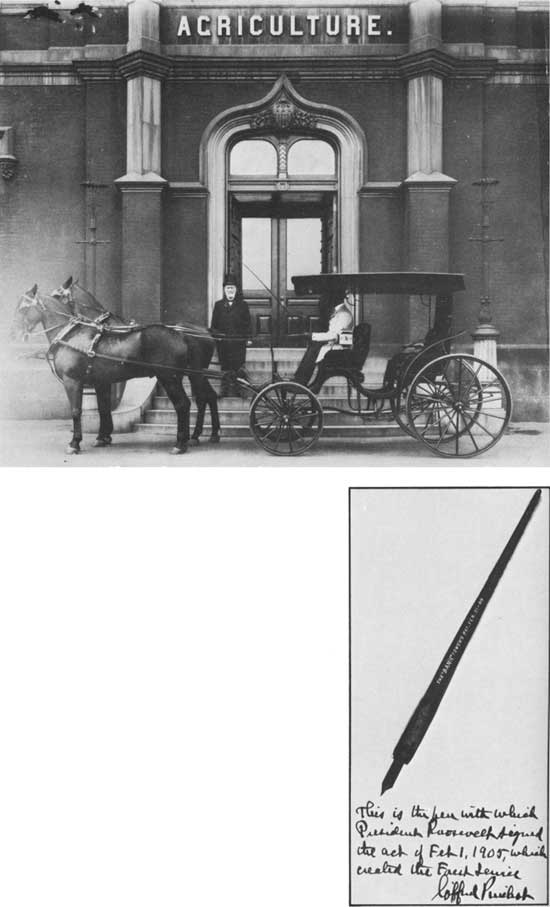

1 (top). Secretary of Agriculture James T. Wilson. (F—523669)

2 (bottom). Pen used by President Theodore Roosevelt to sign

the Act that transferred the Forest Reserves to the Department of

Agriculture and led to the transformation of the Bureau of Forestry into

the Forest Service. (F—305150)

|

Sidelights (1905-1916)

The American Forest Congress in January 1905,

sponsored by the American Forestry Association with the aid of many

other groups, set the stage for unification of all federal forestry work

within the Department of Agriculture. Congress acted 3 weeks later to

transfer the Forest Reserves from the Department of the Interior,

thereby creating the Forest Service.

In 1908, President Roosevelt held a Conference of

Governors to consider the Nation's forestry problems. Out of this

historic gathering came the first inventory of our natural

resources.

More than 148 million acres were added to the

National Forests during Theodore Roosevelt's presidency, 1901-1909.

A hero emerged from the worst of the 1910 forest

fires. He was Ranger Edward Pulaski, who saved all but 6 of his trapped

crew of 45 firefighters by leading them to an old mine tunnel.

"In the administration of the forest reserves it must

be clearly borne in mind that all land is to be devoted to its most

productive use of the permanent good of the whole people, and not for

the temporary benefit of individuals or companies. . . .

". . . where conflicting interests must be reconciled

the question will always be decided from the standpoint of the greatest

good of the greatest number in the long run."

James Wilson

Secretary of Agriculture

(These lines taken from a letter dated February 1,

1905, from the Secretary of Agriculture to Gifford Pinchot, Chief

Forester, set down the guides and charter of the new forest agency on

the date of the transfer of the Forest Reserves to the Department of

Agriculture.)

|

|

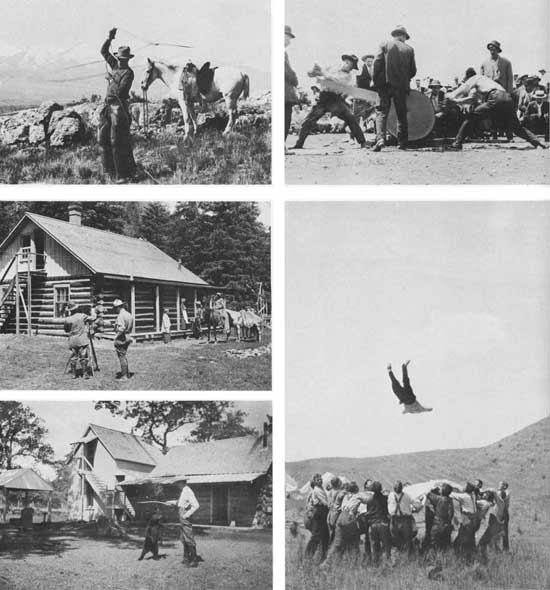

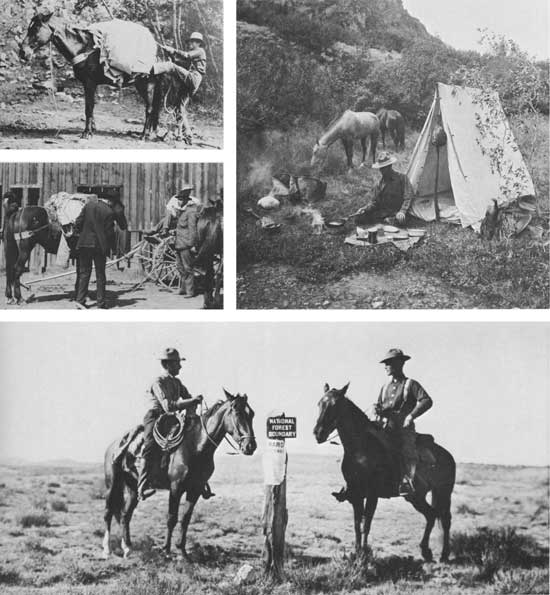

1 (top left) & 2 (middle left). Forest Ranger examinations

in the early years were practical and rigorous. Candidates had

to know how to throw a diamond hitch and pack a horse, show their

mounts, and ride. (Harold Greene, F—71225) 3 (top right). Long days and overnights were an

accepted part of the job, as this lone ranger attests. This was

in 1914 on the Wasatch National Forest, Utah. (F—21043A) 4 (bottom). Most jobs

in the field called for travel by horseback. This was the way the

original boundaries were marked on the San Isabel National Forest,

Colorado, in 1911. (F—00367A)

|

1905-1916

|

|

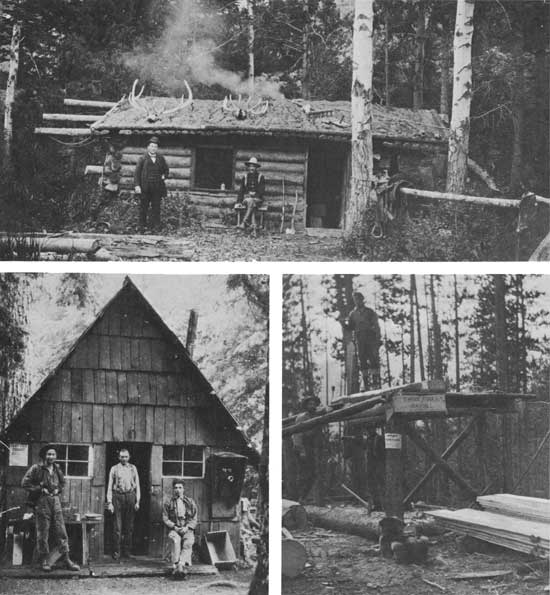

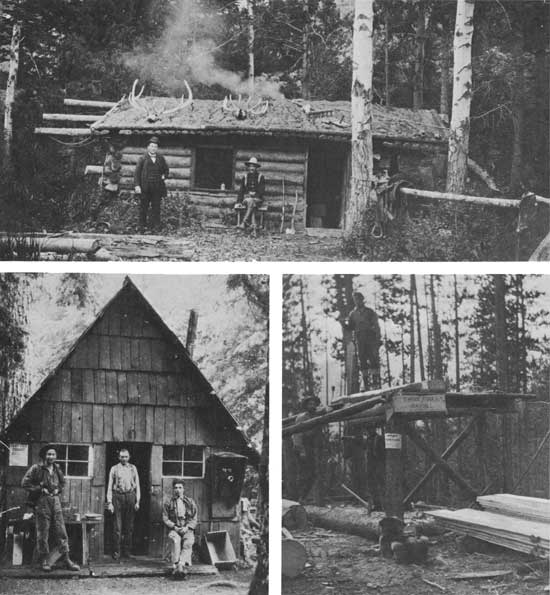

The first Forest Service homes and stations were rustic affairs:

cabins and houses adapted to the outdoor environment and rugged

way-of-life. 1 (top). Ranger Station on the Shoshone National

Forest, Wyoming, built about 1905. It may be the first one built

by the Forest Service. (Forest Service, Region 2, 7300) 2 (bottom left). This was an administrative

center within the Columbia (now Gifford Pinchot) National Forest,

Washington, in 1910. (F—514644) 3 (bottom right). Homegrown, whipsawn

lumber helped build Ranger Stations on the Flathead National

Forest, Montana, in 1908. (F—203047)

|

|

|

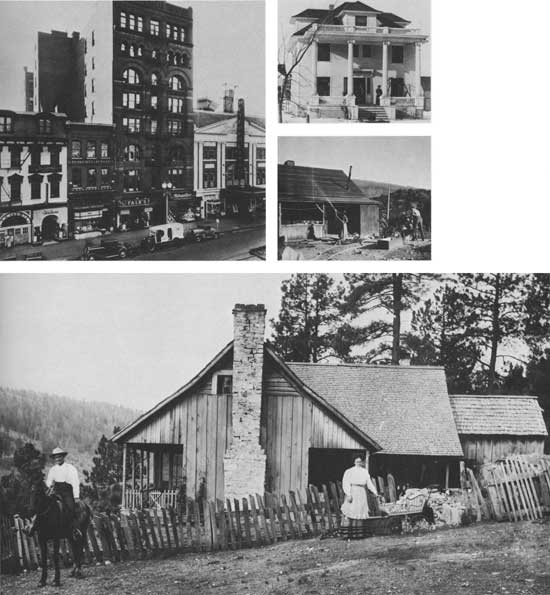

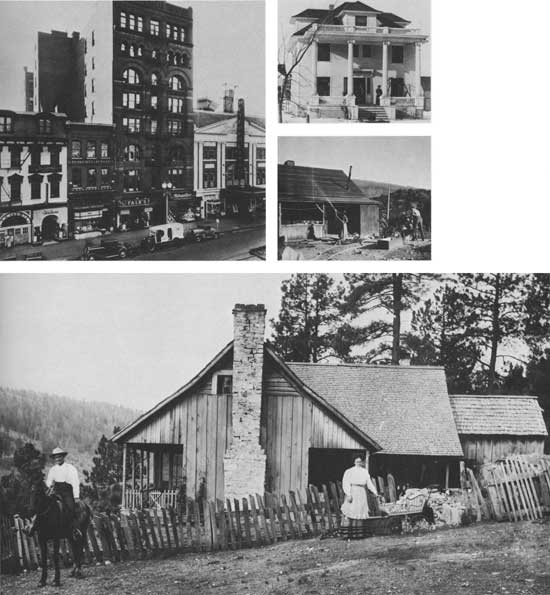

1 (top left). Meanwhile, back in Washington, D.C., Forest Service

headquarters occupied prominent downtown space for more than a

quarter of a century. (F—403371) 2 (top right). This was the first home of

the Forest Products Laboratory (Madison, Wisconsin), destined for

leadership in the field of research in wood utilization. (Forest Products

Laboratory, M 120 172) 3 (middle

right). The Forest Service Ranger's family was prepared in case of

fire at this Ranger Station on the Cibola National Forest, New

Mexico (July 1911). (F—02322A) 4 (bottom). The good life! This was the

Ranger Station in Aquachiquita Canyon, Lincoln National Forest,

New Mexico, in 1908. (F—53108)

|

|

|

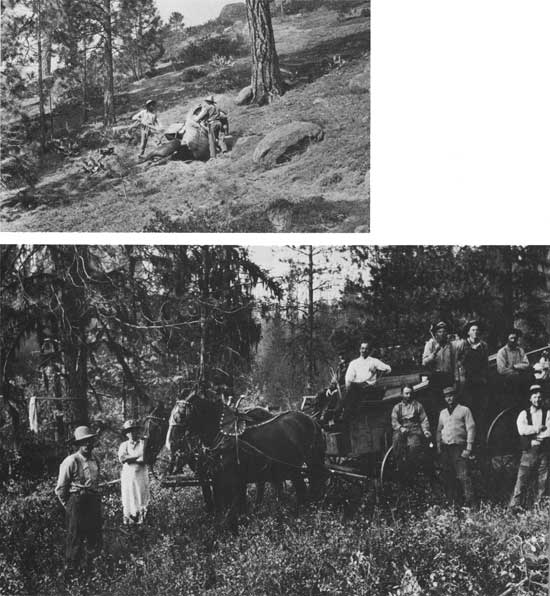

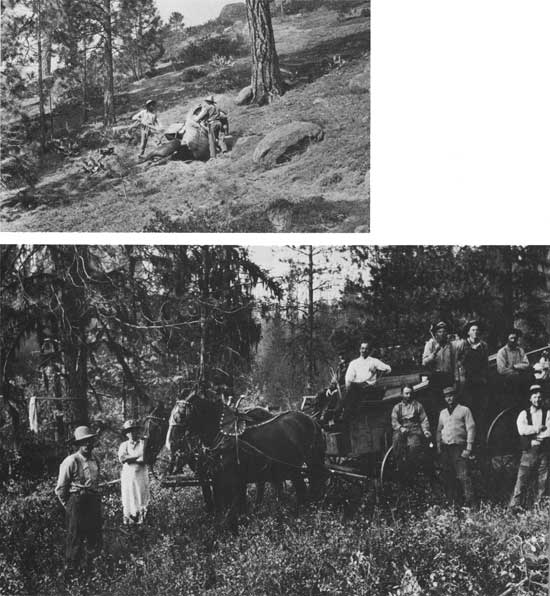

1 (top). Oops! Traffic mishap on the Eldorado National Forest,

California, one summer day in 1914. (F—18462A) 2 (bottom). First load over

a new road carried office equipment for the Priest River Experiment

Station in the Kaniksu National Forest, Idaho (1911). White-shirted

Raphael Zon, on wagon seat, was a Forest Service Research pioneer and,

for many years, an Experiment Station Director. (The Priest River

Station was transferred to Missoula, Montana, in 1916 and Priest

River became an experimental forest.) (F—2265A)

|

|

|

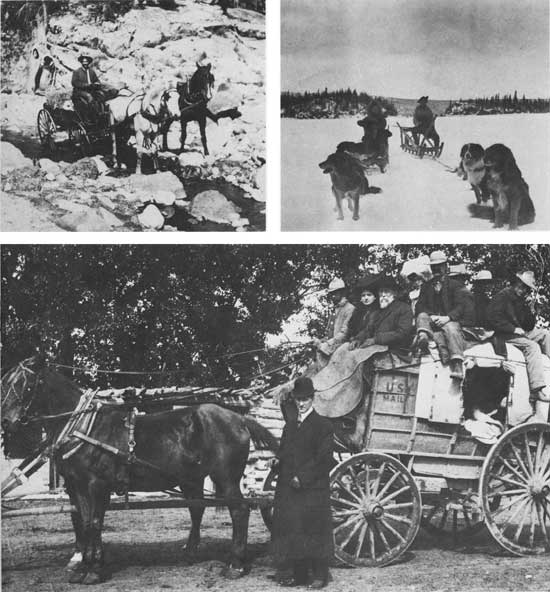

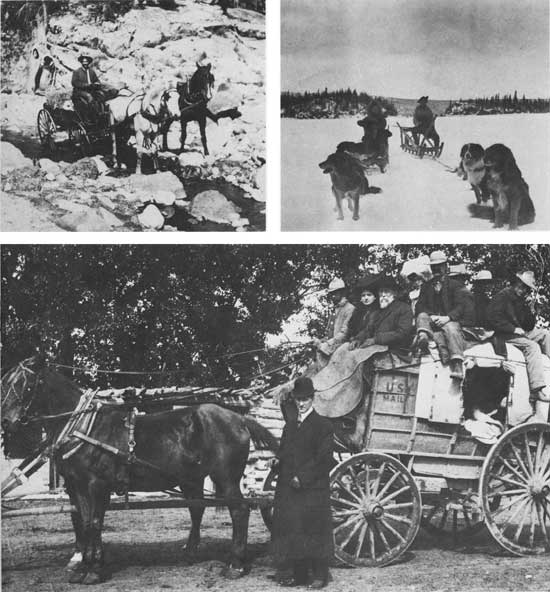

1 (top left). Believe it or not, this creek bed was the easiest

route to travel into the back country of the Crook (now Tonto)

National Forest, Arizona, in 1910. (Harold Greene) 2 (top right). Dog sledding

was the best mode of winter travel on the Chugach National

Forest, Alaska, in 1914. (F—18653A) 3 (bottom). A popular travel vehicle

of the early 1900's, this old stage coach often carried 16 passengers

and baggage 54 miles over the Bitterroot Mountains from Red

Rock, Montana, to Salmon, Idaho. (F—84341)

|

|

|

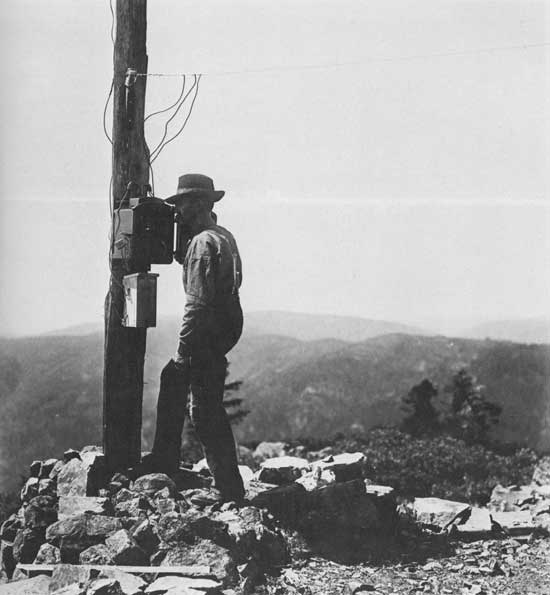

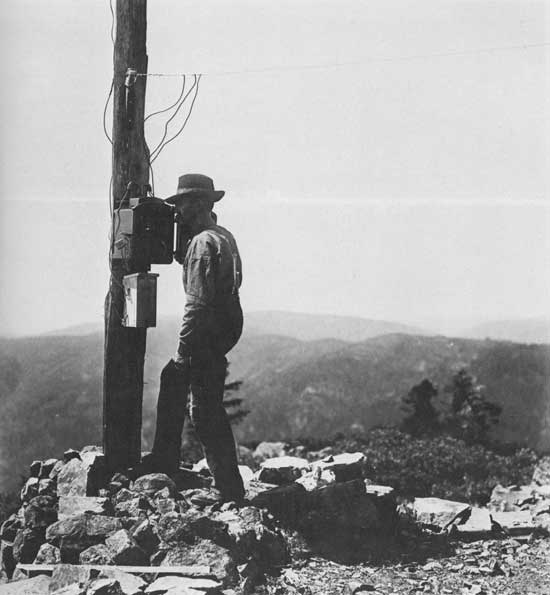

1. Forest officers on patrol used either a small portable telephone

that could be hooked into a temporary field line or permanent call

boxes to maintain contact with Ranger Station headquarters. (F—21039A)

|

|

|

1. Until portable radios were developed in the 1920's and 1930's, the

single wire telephone line (grounded) was the principal means of

communication with the men working in the National Forests. (F—18020A)

|

|

|

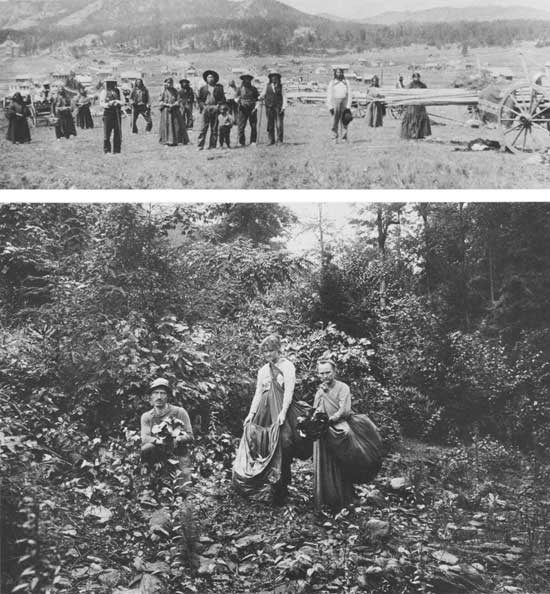

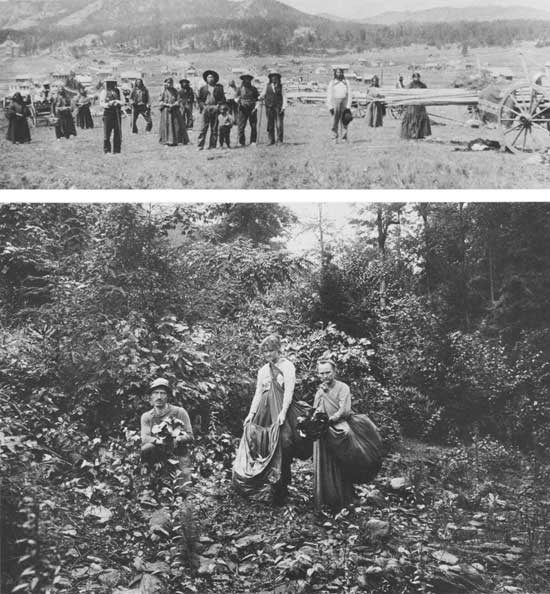

Through the years, Forest Service people have worked with and for all

kinds of people to so manage, protect, and develop the public forest

and range properly that all are properly served—people and natural

resources alike. The principle of "greatest good" has governed the

conservation movement in America. 1 (top). Local residents used timber

from the Black Hills National Forest, South Dakota, on a free-use basis

in 1913. Today free-use is largely limited to firewood from the National

Forests. (F—15626A) 2 (bottom). In 1913 a North Carolina mountain family depended

on the Pisgah National Forest to produce galax, useful in making wreaths

and other floral decorations. (F—15482A)

|

|

|

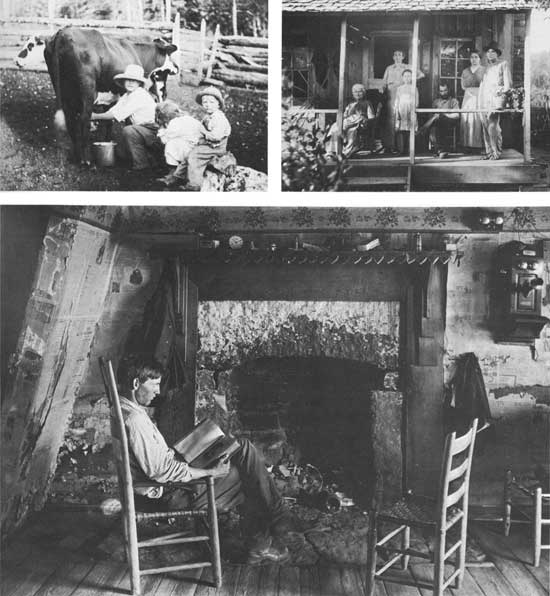

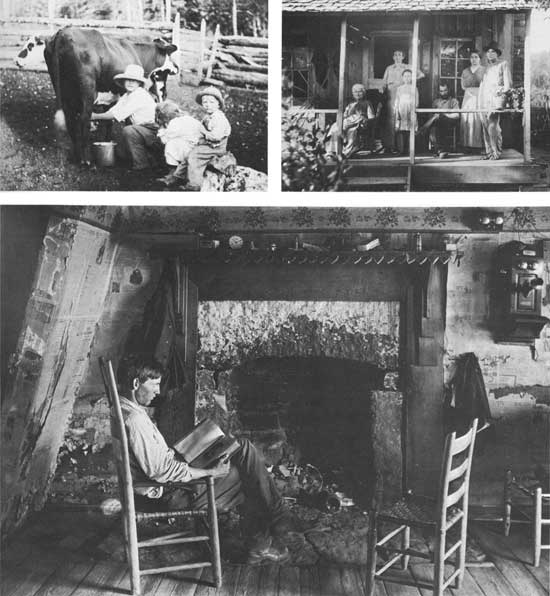

1 (top left). A daily chore at a homestead within the boundaries

of the Manti-LaSal National Forest, Utah, in 1912. (F—14762A) 2 (top right).

These were hardy homesteaders in the Ozark National Forest,

Arkansas, in 1914. (F—18090A) 3 (bottom). Shades of "Honest Abe" in a 1914

Ozark homesteader's cabin. (F—18929A)

|

"Without natural resources life itself is impossible. From birth to

death, natural resources, transformed for human use, feed, clothe,

shelter, and transport us. Upon them we depend for every material

necessity, comfort, convenience, and protection in our lives. Without

abundant natural resources prosperity is out of reach.

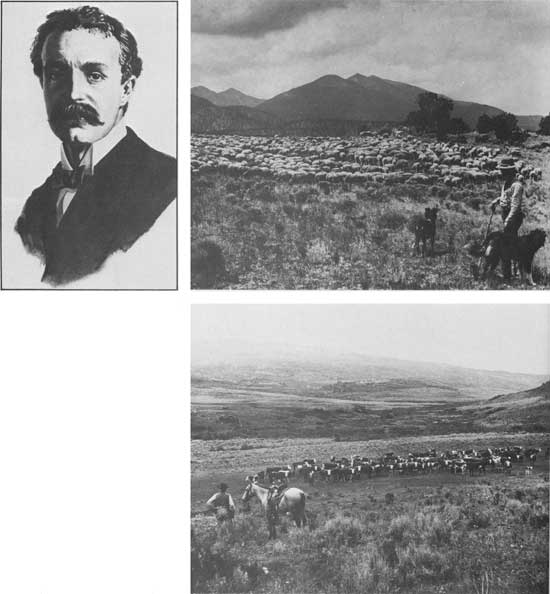

Gifford Pinchot (1898-1910)

|

|

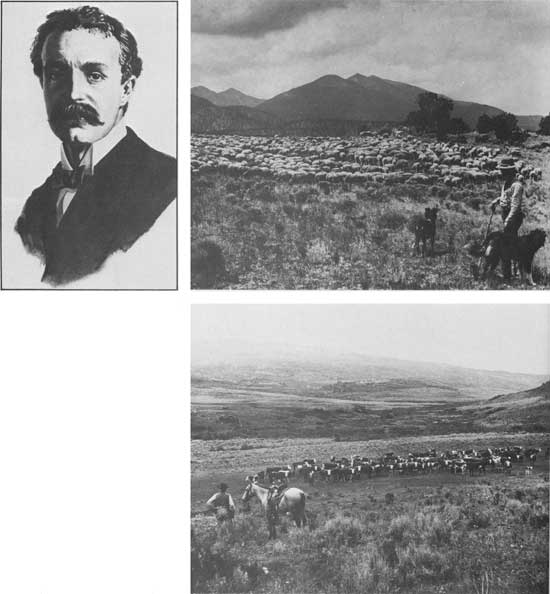

1 (top left). Gifford Pinchot, Chief Forester, 1898-1910. (Drawing by

Rudolph Wendelin) 2 (top

right). Sheep grazing on the Kaibab National Forest, Arizona (1914). (F—19424A)

3 (bottom right). Cattle grazing on the Grand Mesa National Forest,

Colorado (1912). (F—54237)

|

|

|

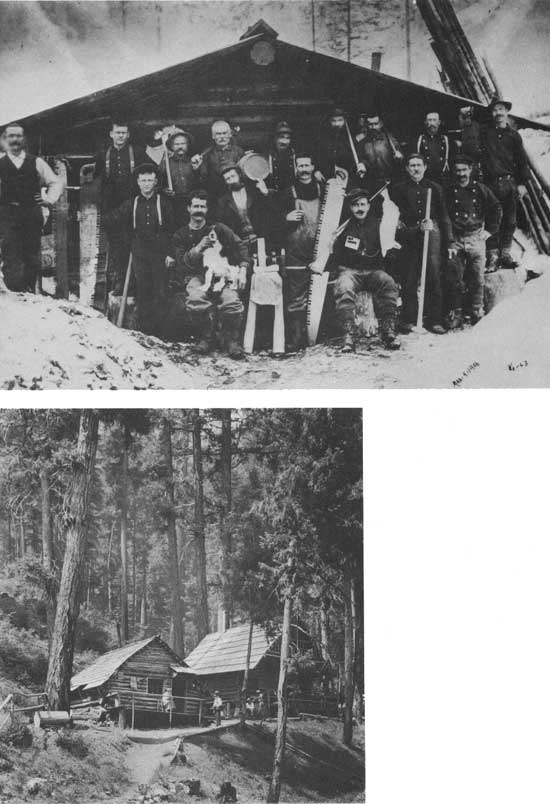

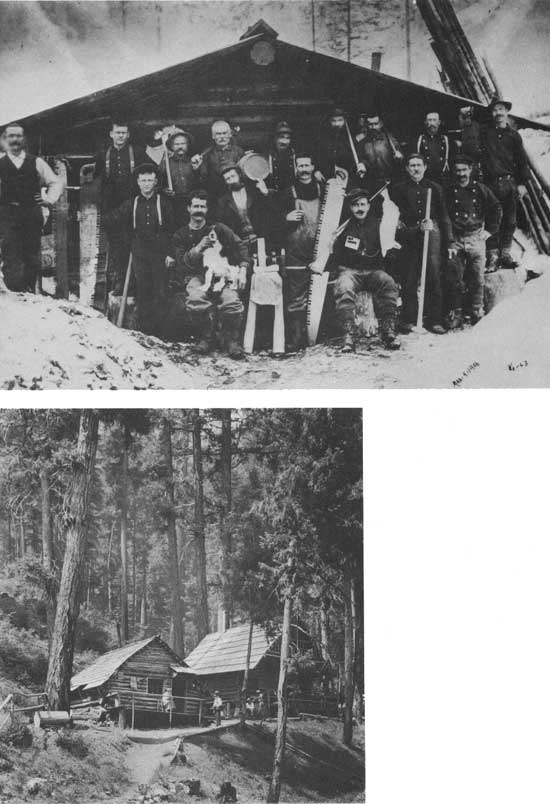

1 (top). Montana lumberjacks in 1906. (F—523661) 2 (bottom). Summer home sites

were made available, under special use permit, in the Shasta National

Forest, California, in 1914. (F—19422A)

|

|

|

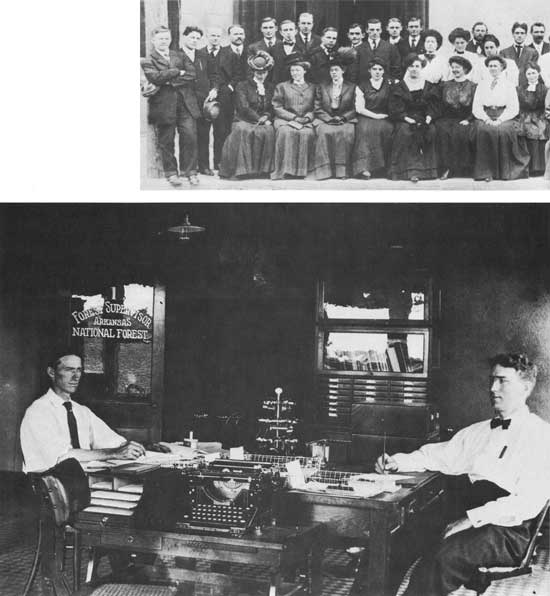

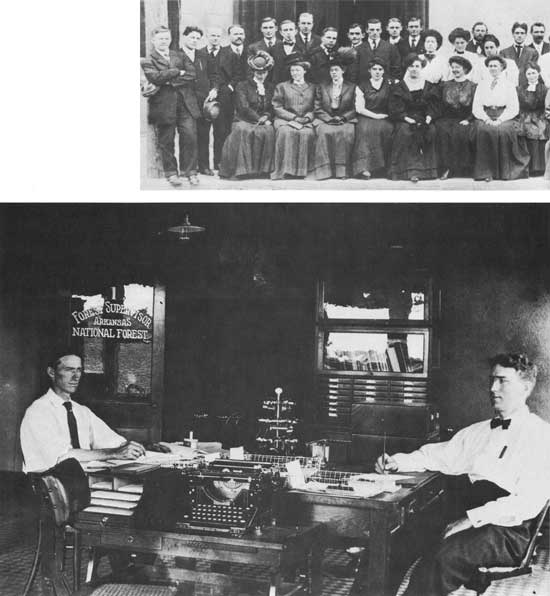

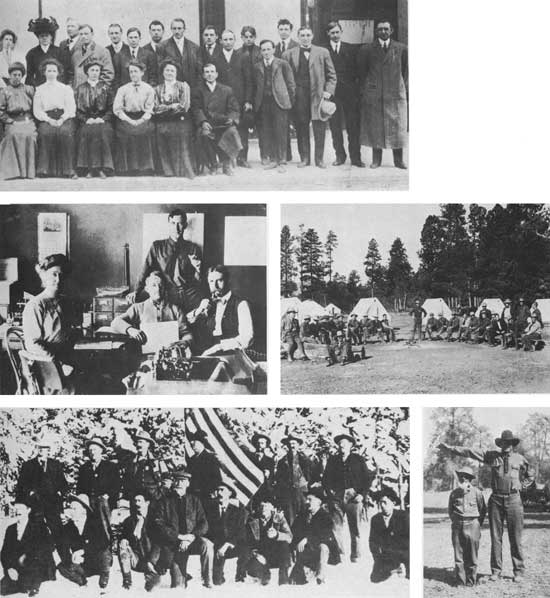

With the passing years, supervisory staffs and office work were

to expand as responsibilities were added. From the earliest days,

meetings were necessary to exchange views and experiences. 1 (top,

continued on next image). The District 3 (now Region 3) staff in

Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1908. (F—242690) 2 (bottom). Forest Supervisor

Samuel J. Record (right) in his office in Mena, Arkansas, September

1908. He was Supervisor of the Arkansas National Forest, now the

Ouachita National Forest. (F—76568)

|

|

|

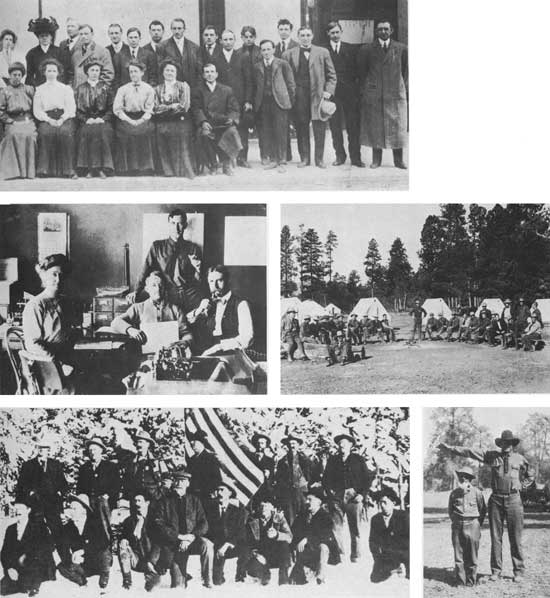

(top, continued from image above). 1 (middle left). Miss Finch, Clerk, Deputy

Supervisor L. E. Cooper, and Rangers Stell and Brown (sitting)

in the Supervisor's Office, Uncompahgre National Forest, Colorado,

in 1911. (Forest Service, Region 2) 2 (middle right). Ranger training meeting on the Coconino

National Forest, Arizona, at Fort Valley in October 1909. (F—90923) 3 (bottom

left). The first Ranger meeting on the Bighorn National Forest,

Wyoming, at Woodrock in November 1907. (Forest Service, Region 2) 4 (bottom right). Time out at a

Forest Service meeting on the Gila National Forest, New Mexico,

in October 1912. (F—14686A)

|

|

|

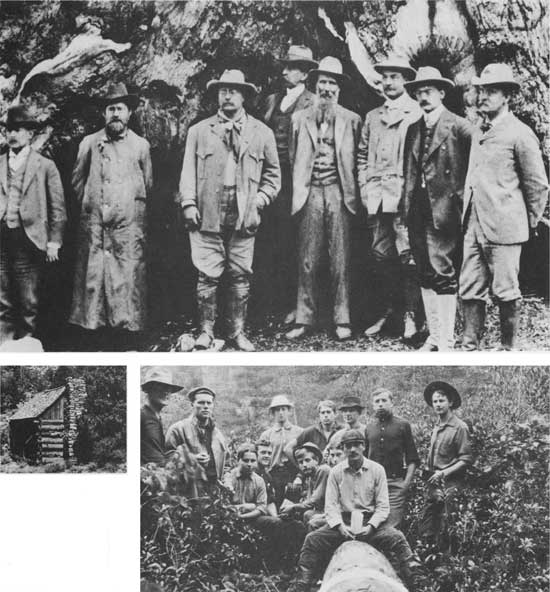

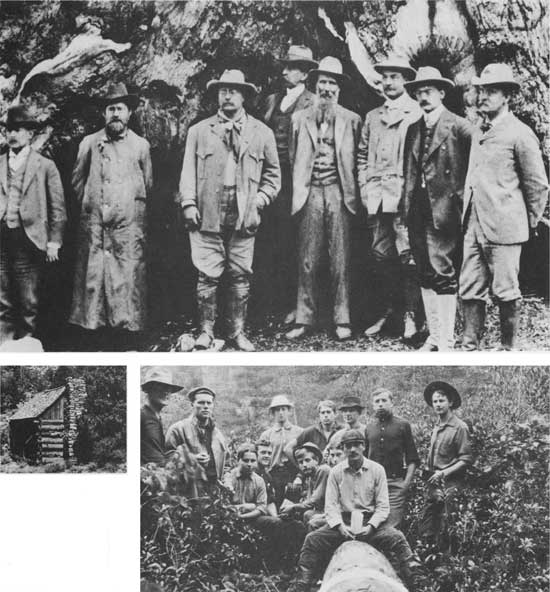

1 (top). A gathering of conservationists in the early 1900's included

President Theodore Roosevelt, Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot (back),

and Naturalist John Muir (fourth from right). The occasion was a field

trip in California. (F—517195) 2 (bottom left). President Theodore Roosevelt once

slept in this old cabin in Nail Canyon, Kaibab National Forest, Arizona. (F—444010)

3 (bottom right). Dr. Carl A. Schenck's Biltmore Forest School. Class

of 1905, in the Pink Beds section of what is now the Pisgah National

Forest, North Carolina. (F—238885)

|

|

|

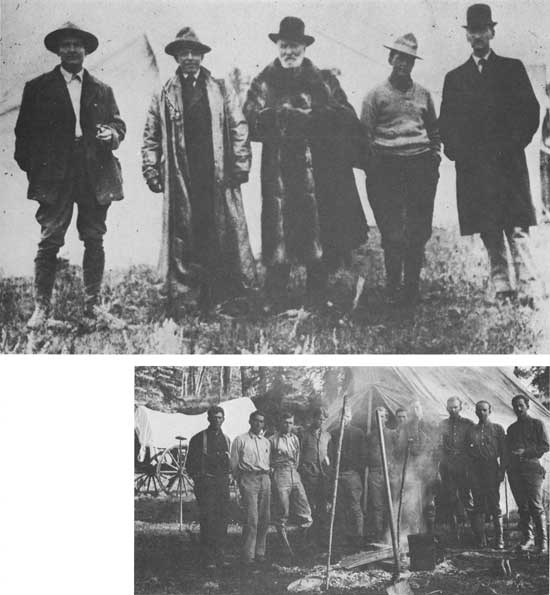

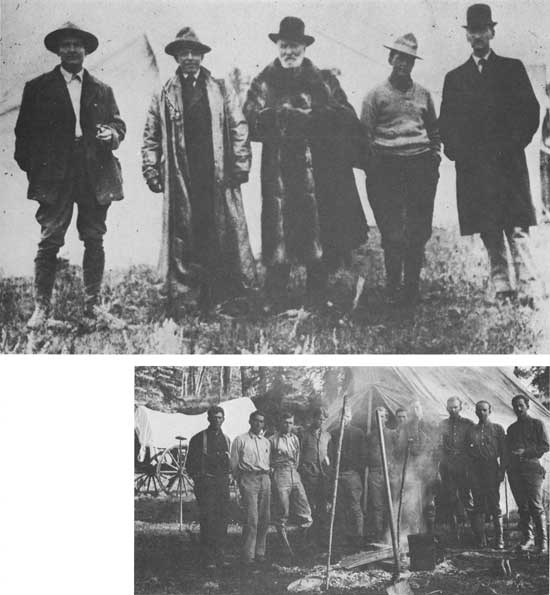

1 (top). A 1912 field trip in the Harney (now part of the Black Hills

National Forest, South Dakota), included, from left to right, Capt. J.

A. Adams, Chief Forester Henry S. Graves, Secretary of Agriculture

James T. Wilson, Roy Smith, and an unidentified man. (F—18515A) 2 (bottom).

A research reconnaissance crew in camp at the Fort Valley Experiment

Station, Coconino National Forest, Arizona, in 1910. (F—93717)

|

|

|

1 (top). Loading a train with ponderosa pine logs at a railroad landing

near Belmont, Arizona, in 1911. (Harold Greene) 2 (bottom). "Big Wheel," 9 feet in diameter,

were used to bring the logs to be loaded. (Harold Greene)

|

|

|

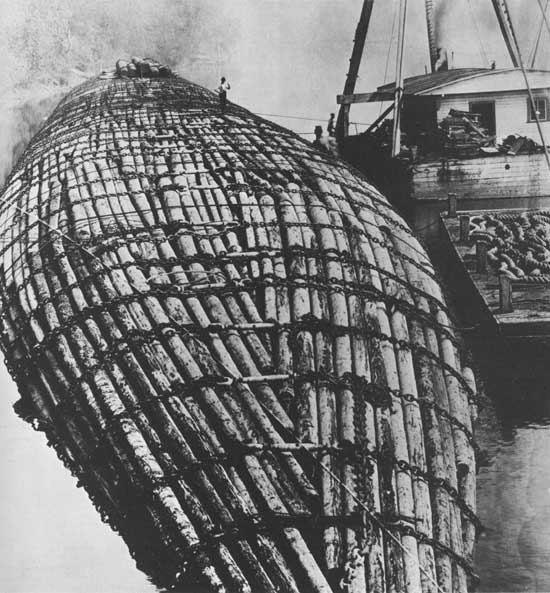

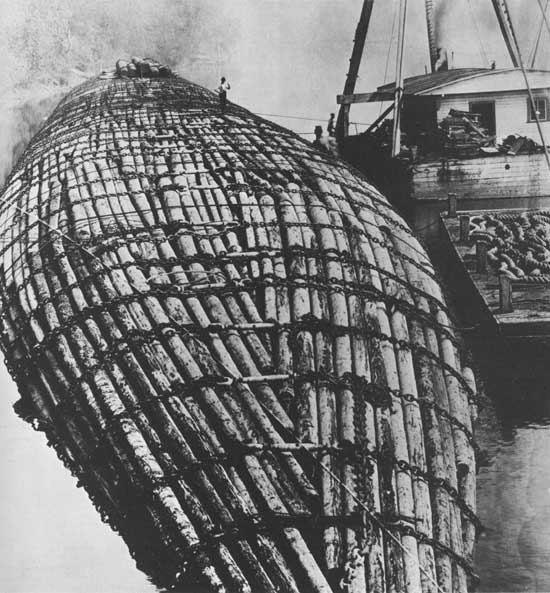

1. En route to the mill. Such log rafts were not unusual in Washington

in 1910. (F—25756)

|

|

|

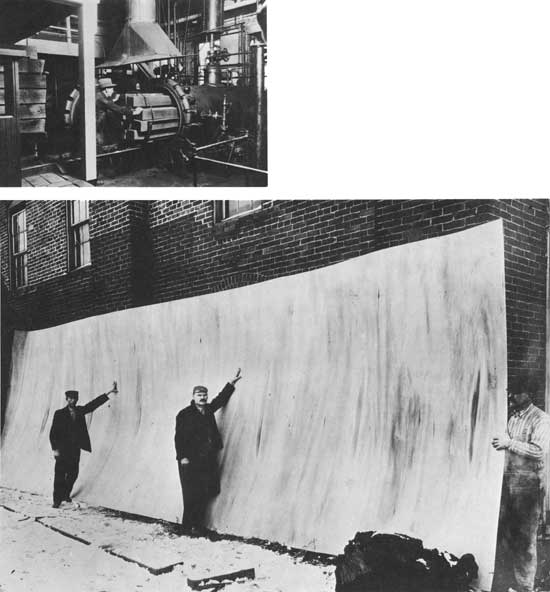

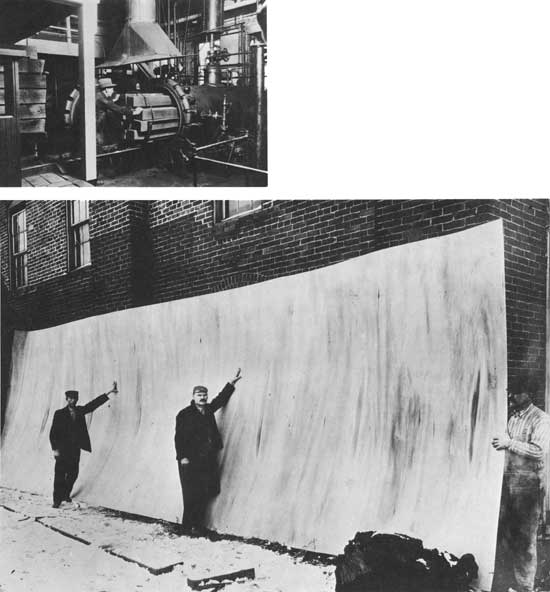

1 (top). Studies in methods of preserving wood occupied scientists at the

Forest Products Laboratory, which opened in 1910 in Madison, Wisconsin. (F—165834)

2 (bottom). Yellow poplar plywood sheet made in 1913. (F—17173A)

|

|

|

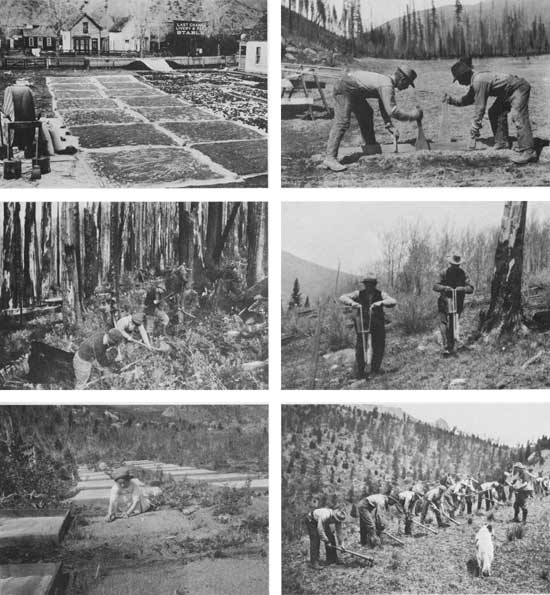

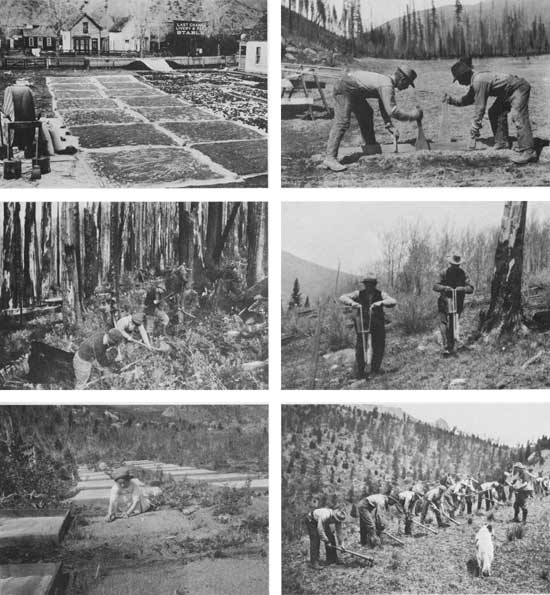

From its very beginning, the Forest Service has given consideration to replanting

cutover and burned-over areas. Much of the land within the newly proclaimed and

purchased National Forests were sorely in need of reforestation. 1 (top left).

Seed collected from ponderosa pine cones were thoroughly dried before planting in the

nursery or afield in the Uncompahgre National Forest, Colorado, in 1912. (Forest Service,

Region 2) 2 (middle

left). New trees were planted to replace the burned ones on the Mount Hood

National Forest, Oregon, in 1913. (F—17219A) 3 (bottom left). Research has long supported

Forest Service management. As early as 1912 studies in nursery practices were

conducted at the Manitou Peak Experimental Area, Pike National Forest, Colorado. (F—11923A)

4 (top right). Seedlings were transplanted in the Savenac Nursery, Lolo

National Forest, Montana, in 1912. (F—11148A) 5 (middle right). The cornplanting method of

putting Douglas-fir seed into the Colorado soil was used in 1911. (F—00860A) 6 (bottom

right). Crews worked to replenish the land on the Pike National Forest,

Colorado, in 1913. (F—17689A)

|

|

|

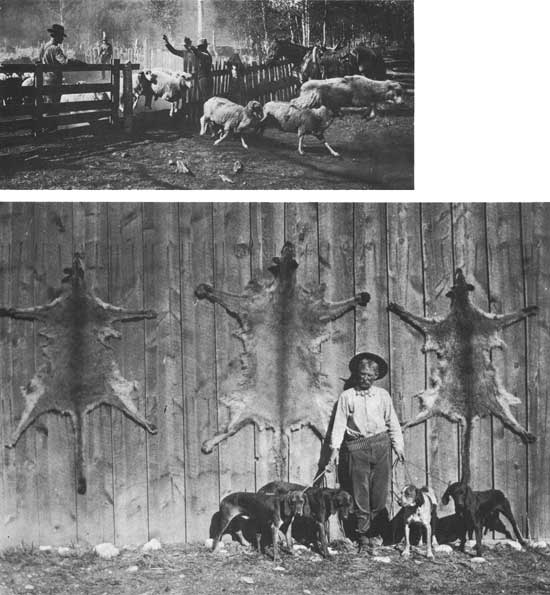

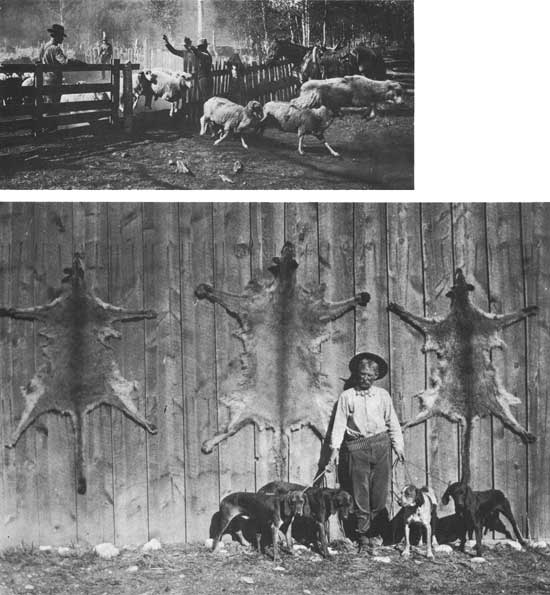

1 (top). On the Wasatch National Forest in Utah, in 1914, this was one way that

sheep heading into the open range were counted. (F—21582A) 2 (bottom). Trapper Jim Owens

was well known for his predator control activities on the Kaibab National Forest,

Arizona, in the early 1900's. This later led to severe overpopulation of deer

and to their widespread starvation. Increasing knowledge of natural processes

showed predator control to be misguided; the practice was halted except as a

solution to a specific problem in a specific area. (F—11168A)

|

|

|

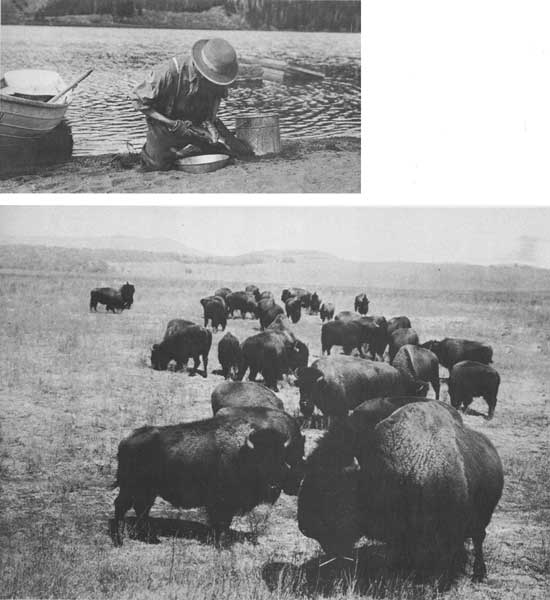

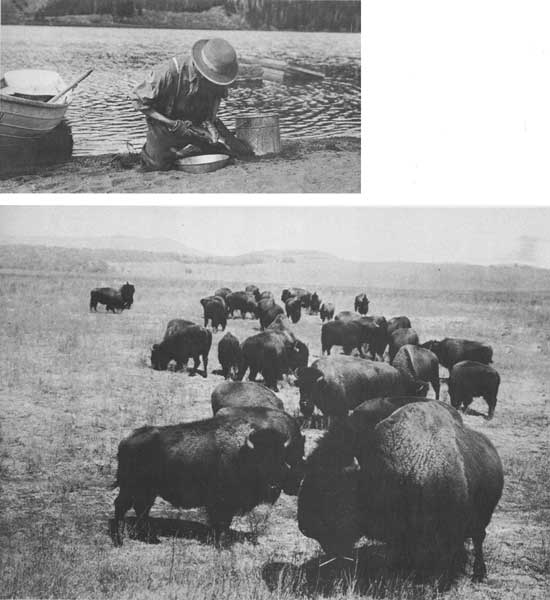

1 (top). On the Pike National Forest, Colorado, in 1911, a technician

fertilized trout eggs by "stripping" the male fish. (F—581A) 2 (bottom). In 1913,

the Forest Service was concerned with maintaining one of the last

then-remaining buffalo herds. This herd was established on the old

Wichita National Forest, Oklahoma, in 1907. This Forest became a

National Wildlife Refuge in 1936. By then Texas Longhorn cattle had

been added to the area. (F—17757A)

|

|

|

1. A Sunday drive among the giant Redwoods in the Six Rivers National

Forest, California, was a popular diversion in 1913. (F—18023A)

|

|

|

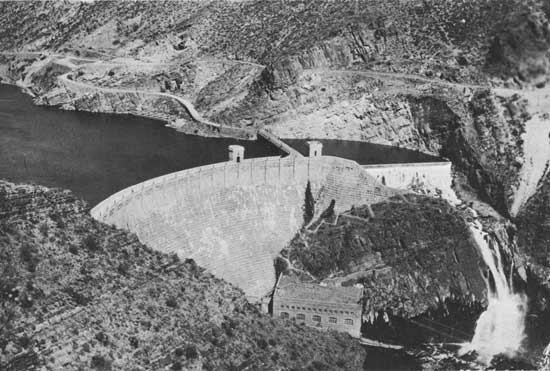

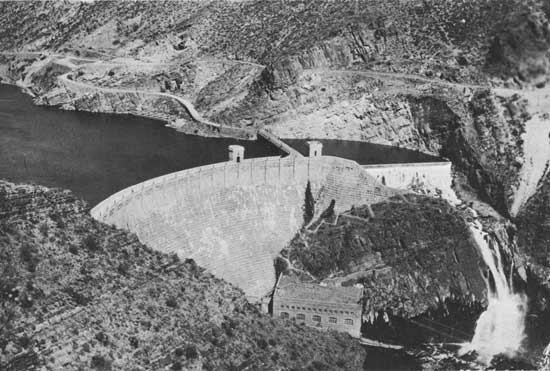

Water—one of the major natural resources—has always figured

heavily in Forest Service planning and administration. 1. This is a

1915 view of the Roosevelt Dam and Power Station (Bureau of Reclamation)

in the Tonto National Forest, Arizona. (F—29846A)

|

|

|

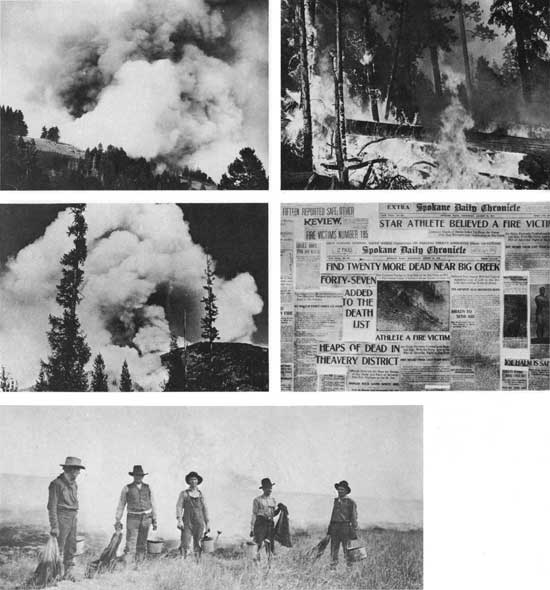

1. Forest fires resulting from lightning storms and from human carelessness

have hampered good forestry since the beginning of America's forestry effort.

In 1910, particularly, fires raged causing great damage and loss of life in

Idaho, Washington, and Montana. (F—479683)

|

|

|

1. Early morning view of an Idaho fire. (F—480830)

|

|

|

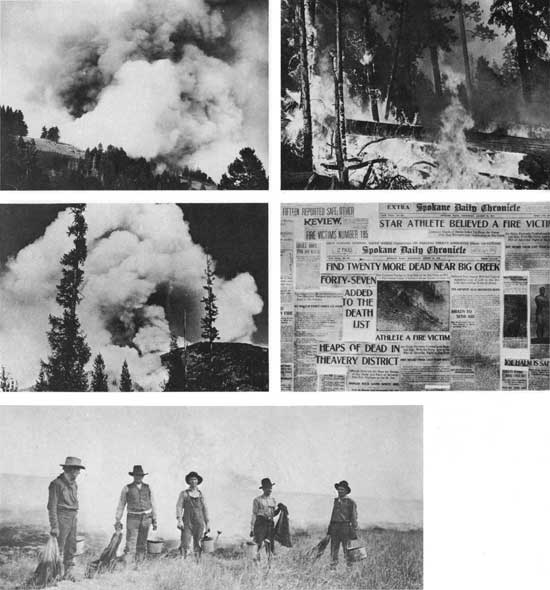

1 (top left). The Northwest had a rough time with fires in 1910. In the

Wallowa National Forest, Oregon, the Sleepy Ridge fire roared out of control

for a while and left in its wake destruction and ugliness. (F—185751) 2 (middle left).

Smoke column rises from a fire on Montana. (F—399997) 3 (top right). Forest fire in

Oregon. (F—468960) 4 (middle right). Copy of newspaper articles chronicling the 1910

fires in Montana. These fires claimed large numbers of victims and millions

of dollars in losses. (F—246027) 5 (bottom). The men were tough, their equipment crude,

as they fought fire in the old Wichita National Forest, Oklahoma, in 1912.

(The Forest is now a National Wildlife Refuge.) (F—12751A)

|

|

|

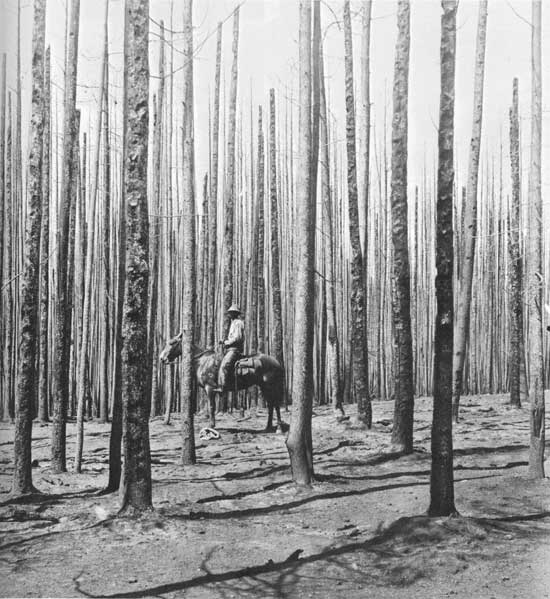

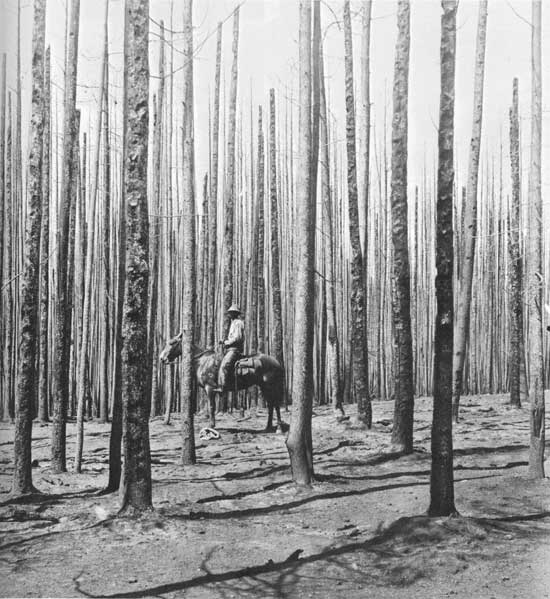

1. Surveying the damage caused by the 1910 Sleepy Ridge fire on the Wallowa

National Forest, Oregon. (F—185752)

|

|

|

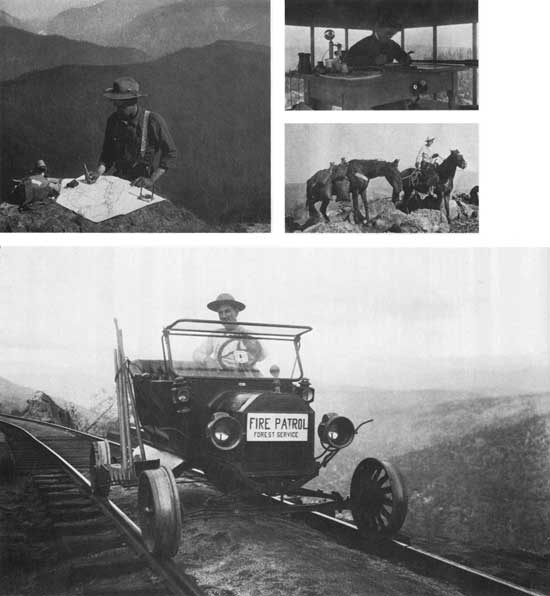

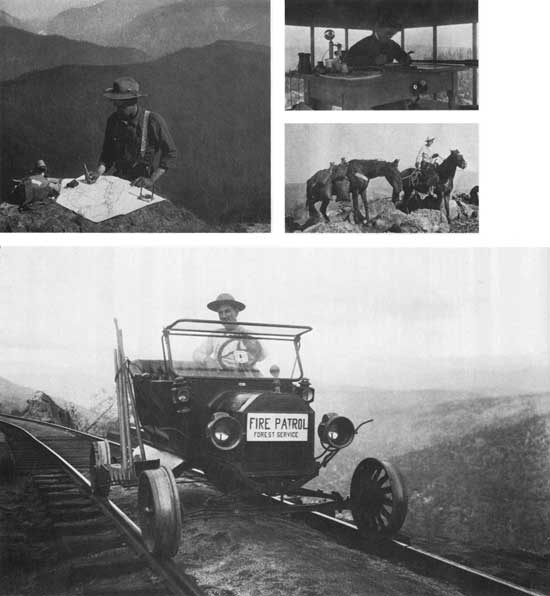

1 (top left). Forest Ranger Griffin used map and compass, a natural overlook,

and a rock "desk" to figure the distance to a smoke just sighted in the Cabinet

National Forest, Montana, 1909. The Cabinet was divided among the Kaniksu,

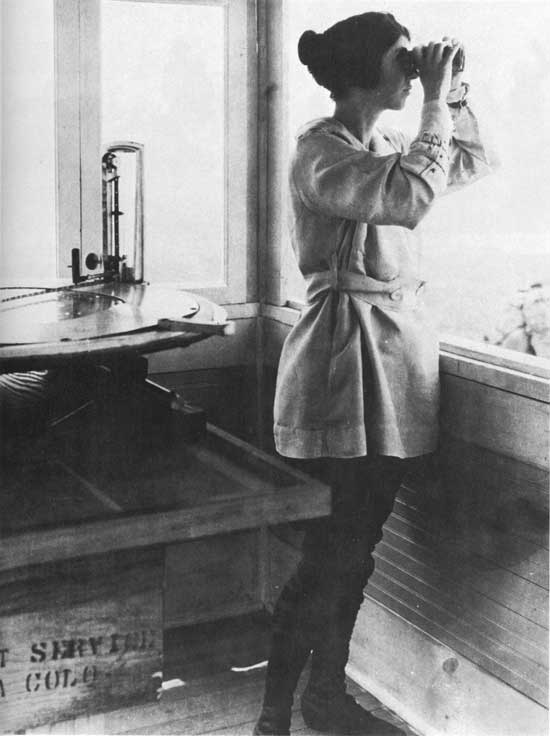

Kootenai, and Lolo National Forests in 1954. (F—59299) 2 & 3 (top right). Harriet

Kelley was her name. In the summer of 1915 she could have been reached at a

lookout tower on the Tahoe National Forest, California, or on the trail

leading up to the tower, hauling water. (F—26755A, F—26756A) 4 (bottom). Ranger Jordan took his patrol

job sitting down with customary Forest Service ingenuity, Sierra National

Forest, California, March 1914. (F—18263A)

|

|

|

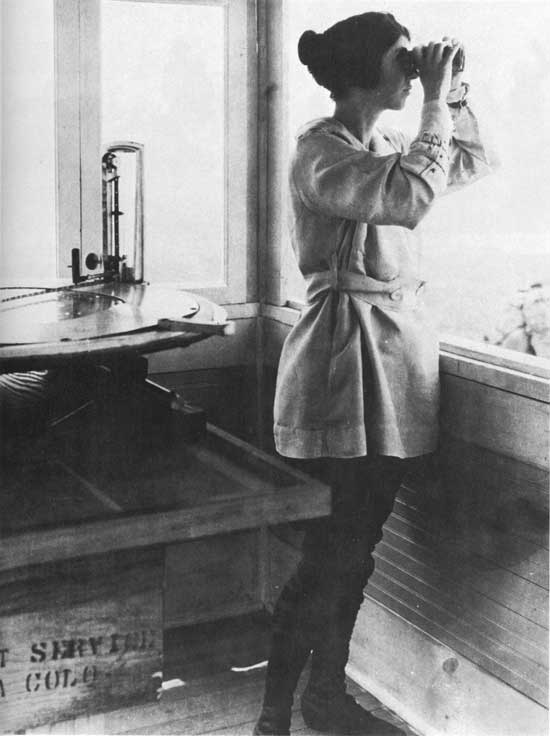

1. Lookouts were conscientious and devoted to duty and the lonely assignment.

Helen Dowe's station in 1919 was the Devil's Head Fire Lookout, Pike National

Forest, Colorado. (F—42829A)

|

|

|

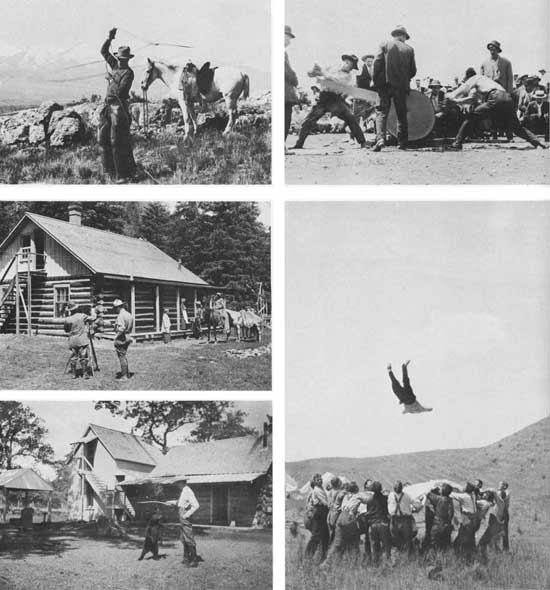

"All work and no play . . ." Well, you know the rest. After all the hard

work, under difficult conditions, Forest Service people found ways to relax

and have fun. 1 (top left). Forest Ranger relaxing on the San Isabel National

Forest, Colorado, 1912. (F—12894A) 2 (middle left). Some say almost every Forest Officer

was born with a camera in his hand. There was much they could photograph in

1914 in New Mexico on the Santa Fe National Forest. (F—19440A) 3 (bottom left). This was

long before Smokey Bear. Supervisor's office, old Wichita National Forest

(now Wichita Mountains National Wildlife Refuge), Oklahoma, 1912. (F—12752A) 4 (top

right). Fourth of July celebration in Williams, Arizona, 1911. The winners:

foresters of the Tusayan (now Kaibab) National Forest. Their time was 3.2

seconds! (Harold Greene) 5 (bottom right). "Up, up, and away!" Planting camp, Nebraska National

Forest, 1914. This is the Nation's only totally planted National Forest,

occupying formerly unforested areas. (F—22227A)

|

|

|

1. Quiet moment at a fire overlook on the Shasta National Forest, California, 1914. (F—19473A)

|

aib-402/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 12-May-2008

|