100 Years of Federal Forestry

Agriculture Information Bulletin No. 402

|

|

|

|

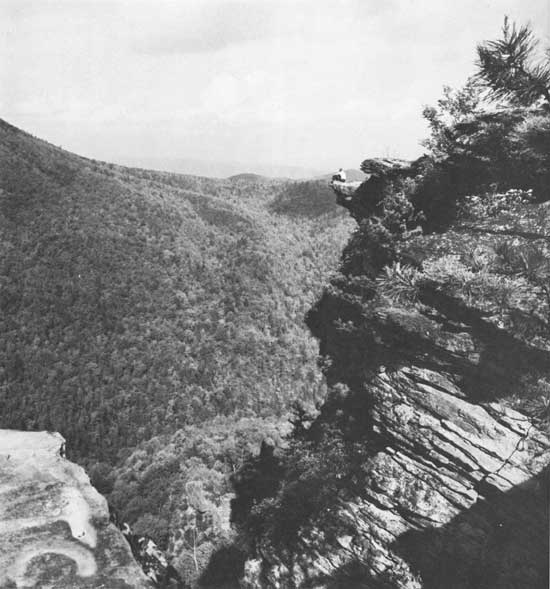

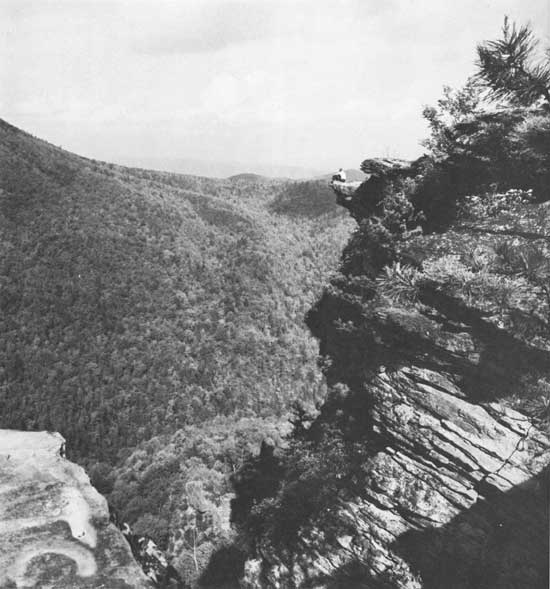

1. Linville Gorge from Wiseman's View in the Pisgah National

Forest, North Carolina. (F—514676)

|

Growing Up, 1917-1945

Highlights

World War I and World War II, during their course and

in their aftermath, set into motion actions and produced events that

were to profoundly affect American forestry and the operations of the

Forest Service. Sentiment among foresters and the general public for

some control over excessive cutting and fire damage on private

timberlands increased after World War I, and the debate over Federal or

State control or a combination of both raged for many years. The former

Forest Service Chief, Gifford Pinchot, led the forces favoring strong

federal controls over private harvesting methods. His successor, Henry

Graves, favored action by the States under federal guidance.

William Greeley, who became Chief in 1920, developed

the landmark Clarke-McNary Act of 1924. This Act greatly expanded

Federal-State cooperation in fire control and reforestation on State and

private forest lands, including cooperation in growing and distributing

tree seedlings. It broadened the authority of the Federal Government to

purchase private forest lands for National Forests. It provided for

studies of forest taxation intended to encourage private forestry, and

for cooperative educational work in farm forestry with farmers. However,

it left out controversial provisions for Federal regulations over

cutting practices on private lands.

State forestry developed rapidly under the impetus of

both the earlier Weeks Law of 1911 and the Clarke-McNary Act. States

began to revise their timberland tax policies, to regulate private

timber cutting, and to set aside State forests. Timber producers

gradually improved their harvesting practices, and formed more fire

protection associations. The American Forestry Association carried on a

grass-roots educational campaign against wildfire in the South. The

Forest Service greatly expanded its lookout system and began aerial fire

patrols. Many more National Forests were set up in the East, Midwest,

and South. Oregon became the first State to regulate private timber

cutting (1941), soon followed by Maryland, Massachusetts, and Minnesota

(all in 1943), and California and Washington (both in 1945).

A comprehensive program of forest research was put

into effect with the McSweeney-McNary Act of 1928, and the first

complete forest survey was conducted during the 1930's. More regional

Federal forest experiment stations were established to pursue all phases

of forest and range land research, including studies in timber, range,

wildlife habitat and watershed management, and in fire, economics, and

utilization of wood products.

The 1677-page Copeland Report of the Forest Service

offered in 1933 a comprehensive plan for more intensive management of

all forest lands, more public forests, and more regulation of private

forests.

The Civilian Conservation Corps program began in 1933.

It helped to relieve the economic distress of the Depression years and

brought vast improvements to the Nation's natural resources. During the

9-year life of the CCC, 2 million men planted over 2 billion trees in 8

years, fought fires, cleared trails, built campgrounds, and improved

public recreation facilities.

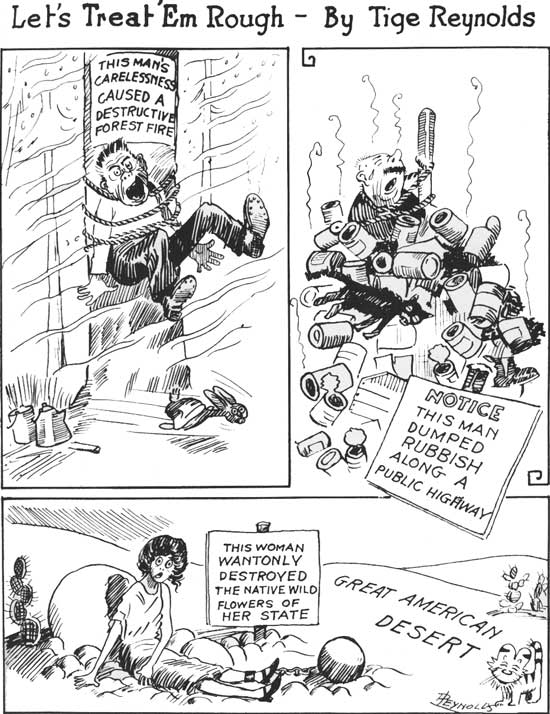

In 1945 the Forest Service's famous Smokey Bear

symbol appeared. The Cooperative Forest Fire Prevention Campaign was

organized earlier during World War II when it became vitally important

to the war effort to protect the Nation's supply of lumber. It was

decided that if people could be reminded to be careful with fire, some

forest fires would be prevented. Smokey Bear was born our of the need of

the campaign for a symbol. Smokey soon became familiar to every adult

and child in America and has been phenomenally successful in preventing

fires caused by human carelessness.

The Forest Service grew up in the period between 1917

and 1945, meeting the challenges of America's rapidly growing needs and

demands. The men and women of the Forest Service were now managing and

developing the precious natural resources in their charge.

1917-1945

|

|

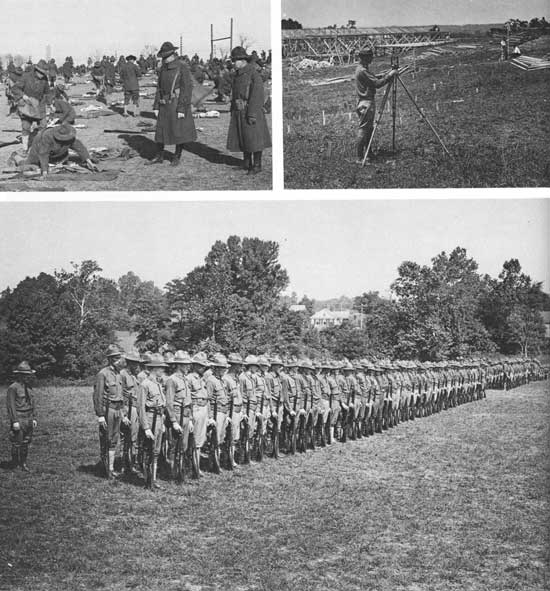

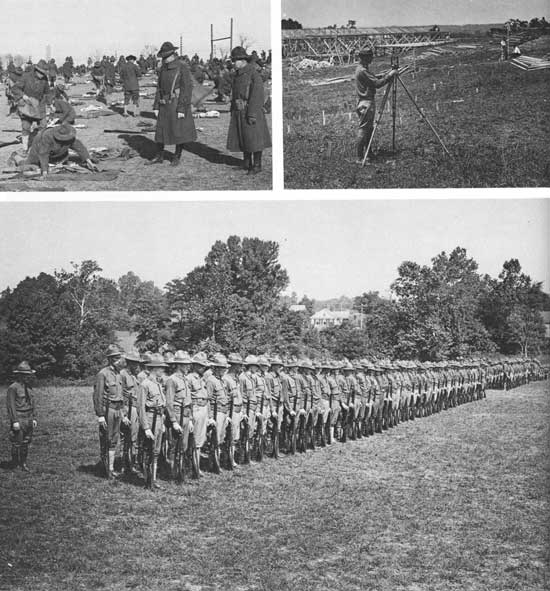

During World War I, many Forest Service men traded their

forest green uniforms for olive drab, as members of the 10th Engineers

(Forestry Battalion), U.S. Army (later merged with the 20th Engineers).

They served at home and abroad in many forestry, engineering, and allied

fields. 1 (top left), 2 (top right), & 3 (bottom). In early 1917, the

Army's Forestry Battalion went into training and was headquartered at

American University in Washington, D.C. (F—35340A, F—34833A,

F—34827A)

|

|

|

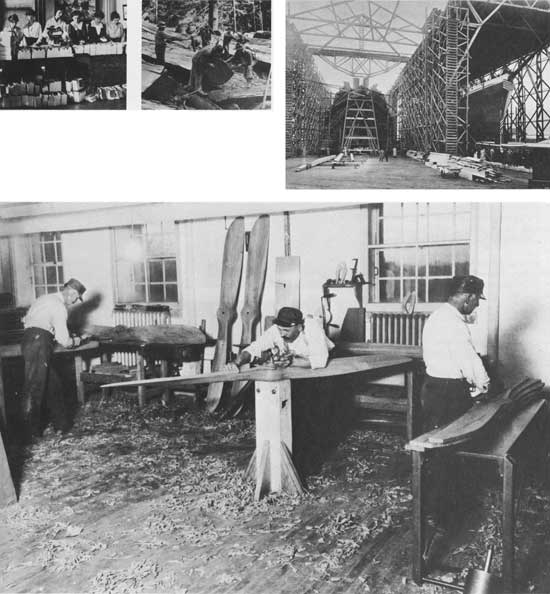

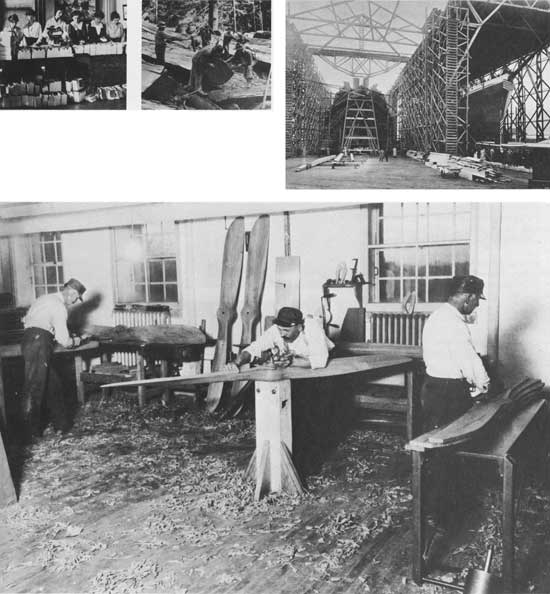

1 (top left). At home, Forest Service women packed

Christmas boxes in 1918 for the men of the Forestry Battalion. (U.S. Forest Service

No. 95—G—33003A, in the National Archives) World War I

created a great need for wood. Some 1918 wartime scenes includes: 2 (top center).

A spruce logging operation in the State of Washington. (F—37959A) 3 (top right). Shipbuilding

in Portland, Oregon. (F—37955A) 4 (bottom). The Forest Products Laboratory was called into

action in 1918 to design wooden propellors for fighter airplanes. (Forest Products Laboratory,

M 141 56F)

|

|

|

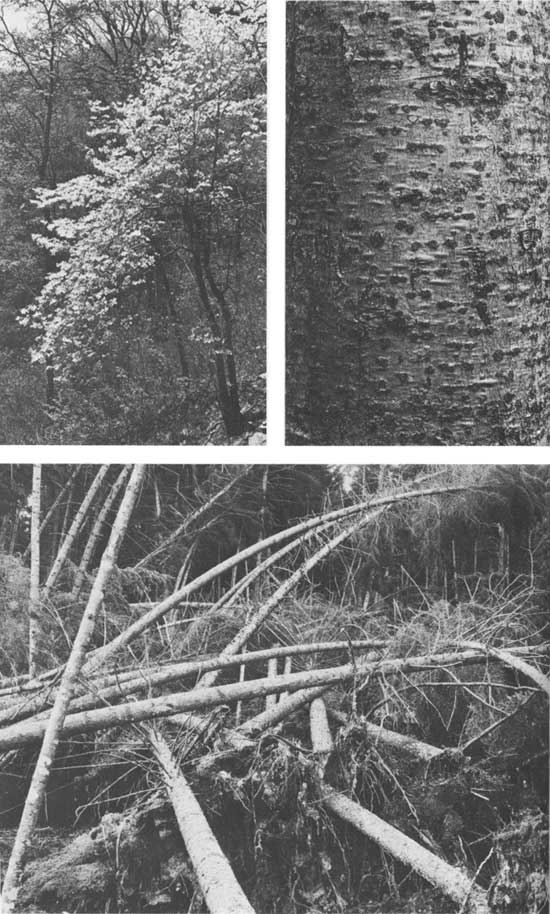

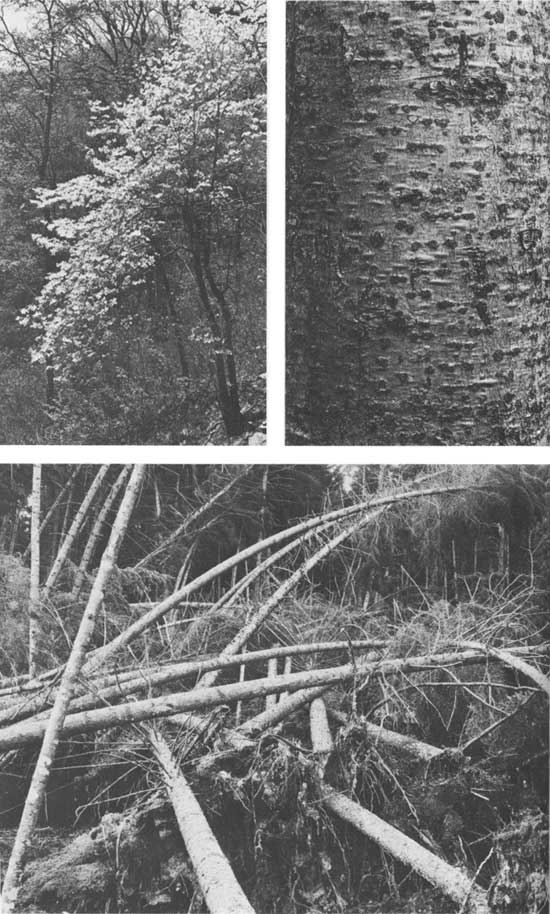

Then as now, what one saw in the National Forests was as varied as the

number of National Forests. 1 (top left). Flowering dogwood in bloom in Macon

County, North Carolina, in April 1941. (F—411278) 2 (top right). The trunk and bark of an

Alpine fir in western Montana, September 1935. (F—308964) 3 (bottom). Damaged by the

September 1938 hurricane, this 65-year-old spruce stand was on the Gale

River Experimental Forest in the White Mountain National Forest, New

Hampshire. (F—369672)

|

Sidelights (1917-1945)

The Forest Service and the War Department joined

forces in 1920 when Army pilots began to patrol the California forests,

spotting fires while still small. Such cooperation led to massive aerial

mapping programs and later to the Forest Service's smokejumping

activities. During World War II, among many special duties, the Forest

Service opened up logging of Sitka spruce in Alaska for fighter

aircraft, coordinated supplies of forest products nationwide, and

helped farmers in California grow guayule plants for rubber.

The State Foresters formed an association in 1920 to

further cooperation among States and with the Forest Service.

In 1921 a National Forest district was set up in

Alaska and two forest experiment stations were opened in the South.

The Forest Service, in 1927, undertook the unusual

job of rescuing the famous Texas Longhorn cattle breed from possible

extinction.

Millions of trees were blown down as the Great New

England Hurricane of September 1938 swept over the Northeast. The Forest

Service was called in to head the salvage operations and worked closely

with the State forestry agencies in the giant task of keeping fire out

of the blown-down timber. In 3 years the Northeastern Timber Salvage

Administration was able to save 700 million board feet of timber for

market.

Under legislation of 1936 and later, the Forest

Service began working with the Soil Conservation Service and other

Federal agencies on flood control and river basin plans and programs to

conserve soil and water resources.

In 1944 an international forestry organization under

the United Nations was started in a committee headed by former Chief

Henry S. Graves. It had been proposed by Gifford Pinchot who enlisted

the strong support of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Forest

Service still provides leadership for the United States forestry

delegation to this unit of the Food and Agriculture Organization.

". . . the public for its own protection

should prohibit destructive cutting by law."

Henry S. Graves (1910-1920)

(Shortly after World War I, Col. Graves, who

succeeded Gifford Pinchot, began to press for public regulation

of timber cutting on private land. Many lumbermen were allowing

their devastated, logged, and burned-over lands to revert to the

counties for unpaid taxes. Few operators, at that time, were

managing their lands to produce continuous crops of timber, called

"sustained yield." However, Graves resigned early in 1920, and his

successor, William Greeley, pursued a program of voluntary cooperation

instead of regulation.)

1917-1945

|

|

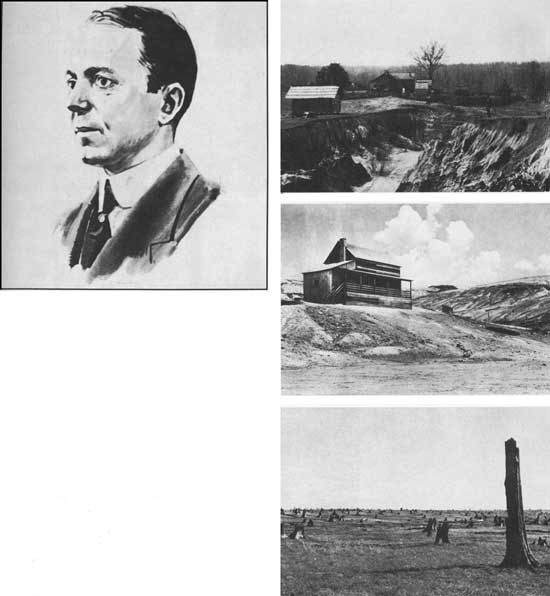

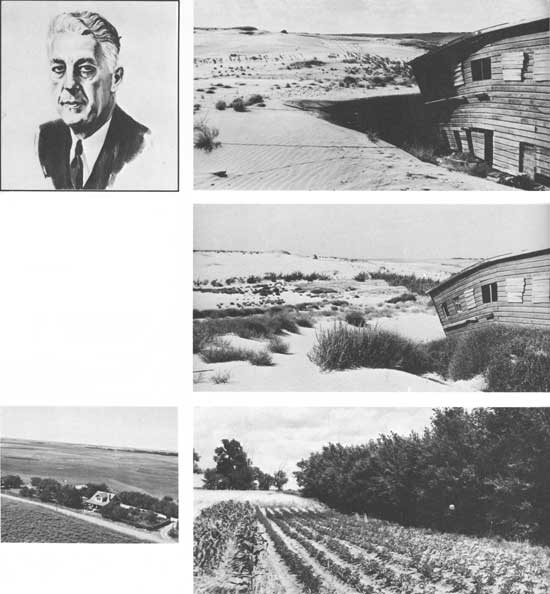

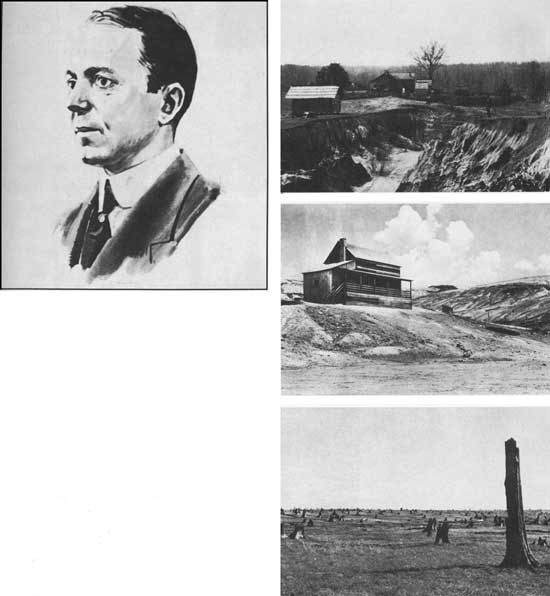

1 (top left). Henry S. Graves, Chief of the Forest Service,

1910-1920. (Drawing by Rudolph Wendelin) Widespread overcutting and disastrous fires

running wild, unharnessed smelter fumes, improper land use generally—they

all took their toll. The Forest Service, through its public forest management,

research, and cooperative forestry activities, became involved. As part of its

statutory responsibilities, it was, and has remained, involved in a nationwide

effort to bring such lands back to productivity and stability. 2 (top right).

Gully undermining a homestead in Mississippi in 1919. (F—40118A) 3 (middle right).

Erosion on a treeless homesite in the Copper Basin Area of Tennessee in 1931. (F—268126)

4 (bottom right). Improperly cutover areas in northern Michigan. (F—467858)

|

"The national forests are no longer primeval solitudes

remote from the economic life of developing regions, or barely touched by the

skirmish line of settlement. To a very large degree the wilderness has been

pressed back. Farms have multiplied, roads have been built, frontier hamlets

have grown into villages and towns, industries have found foothold and

expanded. Although the forests are still in an early stage of economic development,

their resources are important factors in present prosperity."

William B. Greeley (1920-1928)

|

|

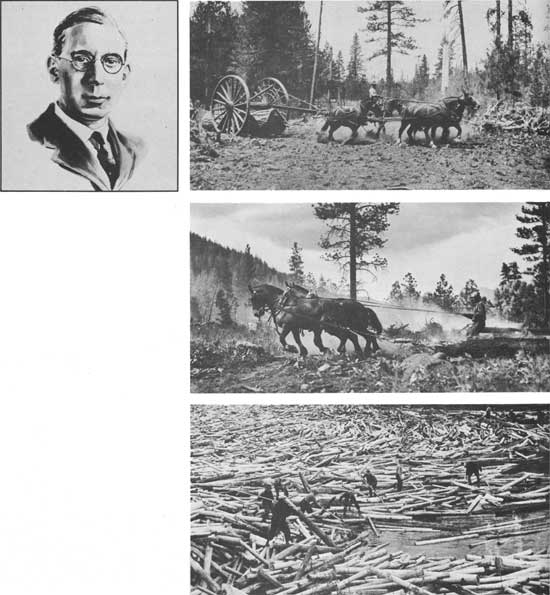

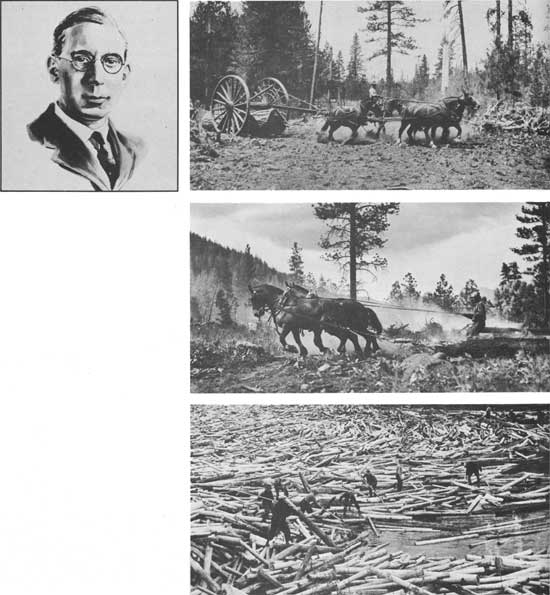

1 (top left). Col. William B. Greeley, Chief of Forest Service, 1920-1928.

(Drawing by Rudolph Wendelin) 2 (top right). Big Wheel logging, Lassen National

Forest, California, 1918. (F—38500A) 3 (middle right). Skidding, Okanogan National Forest,

Washington. (F—401952) 4 (bottom right). Breaking the jam. The Spring of 1937 saw this

last big log drive on the Little Fork River, Koochiching County, Minnesota. (F—418293)

|

|

|

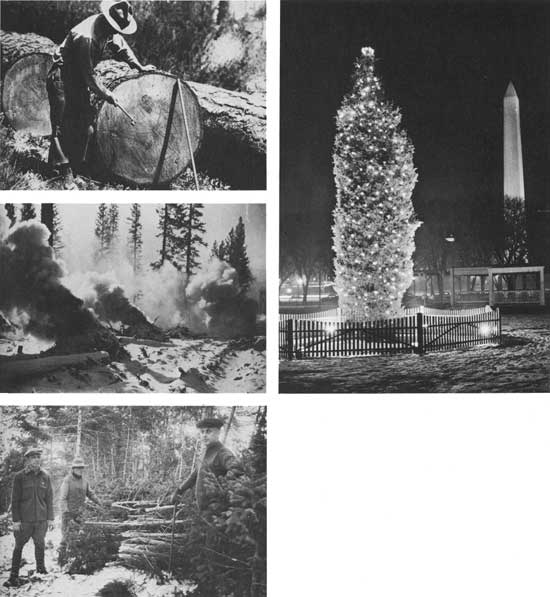

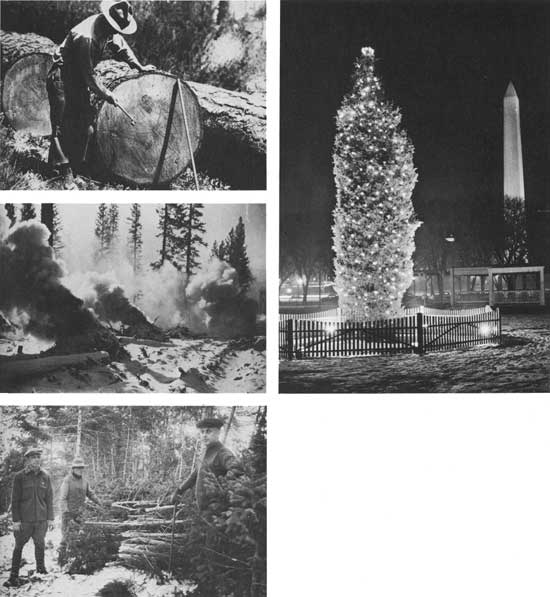

1 (top left). Following a prescribed procedure, the

Forest Ranger or his timber sale assistant cruised the sale area

(estimating in board feet the amount of timber to be sold), marked the

trees to be cut, and supervised the sale operation to prevent

unnecessary damage to the remaining trees and to the soil and to prevent

other irregularities. As a final official act, after scaling, he

stamped the "U. S." with his marking hammer or axe on each log before it

left the National Forest. (Payette National Forest, Idaho, 1925).

(F—199349) 2 (middle left). Through the years foresters

have burned the logging slash after large timber sale operations in the

West, when weather conditions were favorable, to reduce the fire hazard

and aid reforestation. This snow burn took place on the Stanislaus

National Forest, California, in 1924. (F—185048) 3 (bottom

left). One of the forest's most precious gifts—the Christmas tree.

Special areas in many National Forests have for years been designated

for the production and sale of Christmas trees, as here on the Pike

National Forest, Colorado, 1924. (F—401952) 4 (right). Until

a permanent, living tree was selected for such use in 1974, the National

Christmas Tree in Washington, D.C., often came from one of the National

Forests (December 1939). (F—397898)

|

|

|

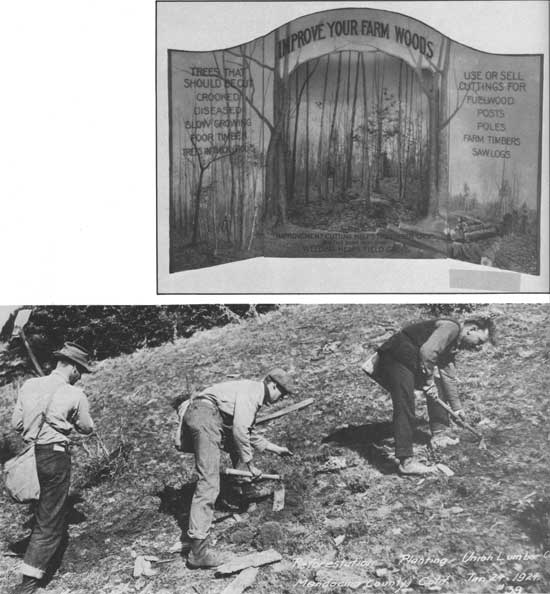

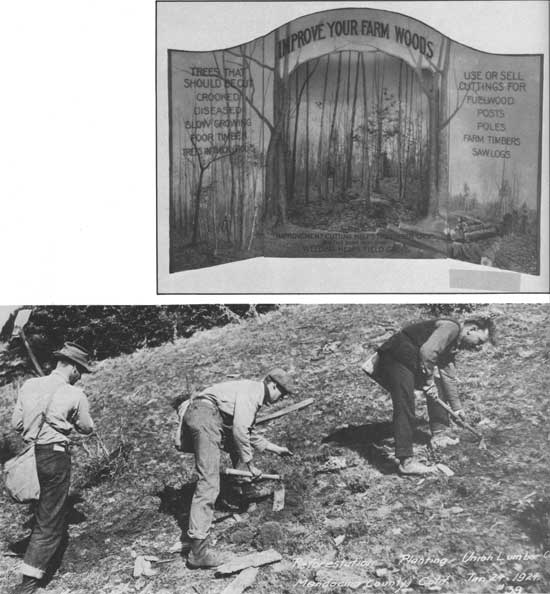

The Clarke-McNary Act (1924) greatly improved forestry practices

on State and private lands, especially fire protection and reforestation. 1 (top).

Promoting good farm forestry, 1930. (F—248795) 2 (bottom). Lumber company reforestation

effort in California in 1924. (F—208823)

|

|

|

1. Trees were tamped into the transplant beds like this in

1927 on the Monogahela National Forest, West Virginia. (F—219007)

|

"Our fundamental concern is to have forestry fit into

the place that belongs to it, in the national scheme of sound land use."

Robert Y. Stuart (1928-1933)

|

|

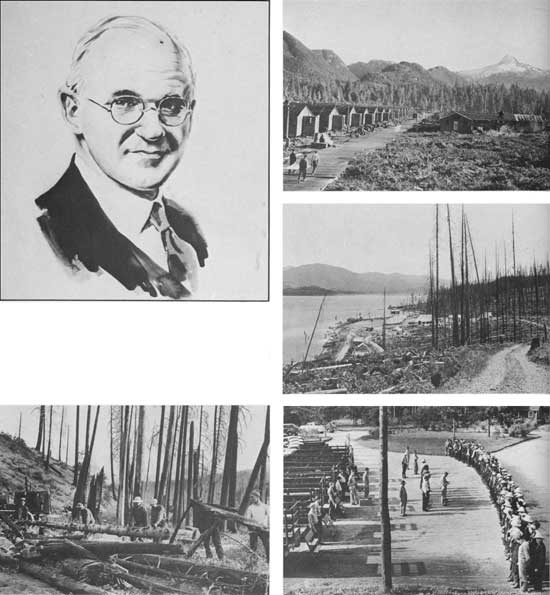

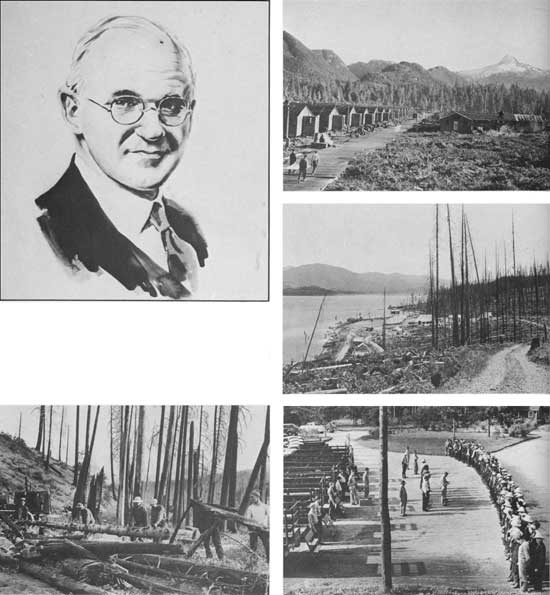

1 (top left). Robert Y. Stuart, Chief of the Forest

Service, 1928-1933. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) began in 1933

and, for 9 years, gave needed employment to hundreds of thousand of idle

young men, aided on the recovery of the national economy, and served

conservation and the cause of practical forestry in tremendous measure.

Participating were the Departments of Labor, War, Agriculture, and

Interior, as well as many State forestry agencies. (Drawing by

Rudolph Wendelin) 2 (bottom left). Clearing land for planting pine

seedlings was one of the CCC activities on the Klamath National Forest,

California. (F—285358) 3 (top right). The camps were

self-contained communities. The contributions to the natural resource

areas made by the men living and working in these camps were

many—in Alaska (then a territory). (F—412947) 4 (middle

right). Idaho (view shows snags that were being felled as a hazard

reduction measure.) (F—278070) 5 (bottom right). Minnesota,

and many other States. (F—401002)

|

|

|

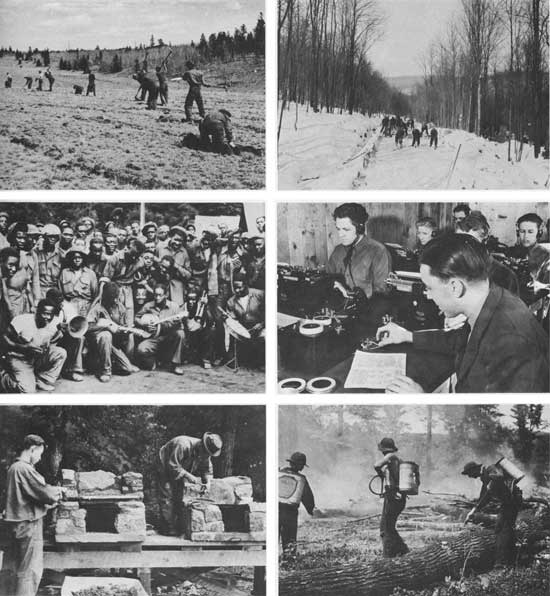

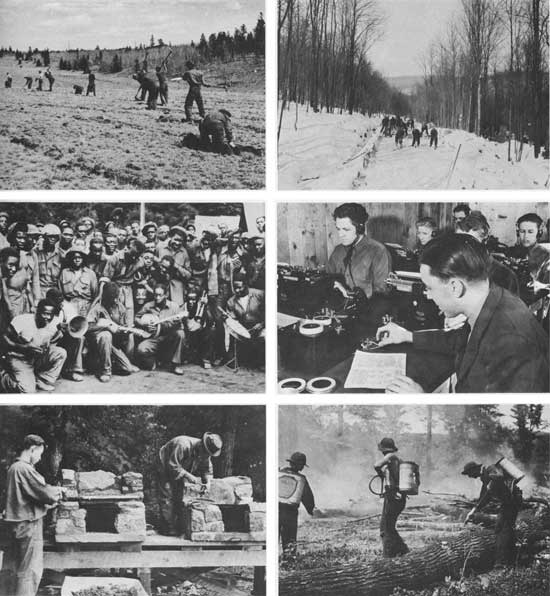

It has been estimated that the CCC men performed over

150 different kinds of work. The tasks varied with the type of

landownership (whether park or forest, National or State, for example)

and with the purposes for which the land and its resources were being

managed and/or protected. 1 (top left). CCC enrollees worked hard

planting ponderosa pine on the Cochetopa National Forest (now part of

Gunnison, Rio Grande, and Pike-San Isabel National Forest, Colorado).

(F—393450) 2 (middle left). And CCC men found time for

recreation after the day's jobs were through. These men found time for

recreation after the day's jobs were through. These men in a

Pennsylvania camp had their own jazz band. (F—278561) 3

(bottom left). They built portable stoves for picnic areas in the

Siskiyou National Forest in Oregon. (F—409167) 4 (top

right). They put down a stone base for a road in Pennsylvania.

(F—317172) 5 (middle right). They learned Morse code in

Utah. (F—407301) 6 (bottom right). And mopped up a fire in

the Ozark National Forest in Arkansas. (F—371158)

|

|

|

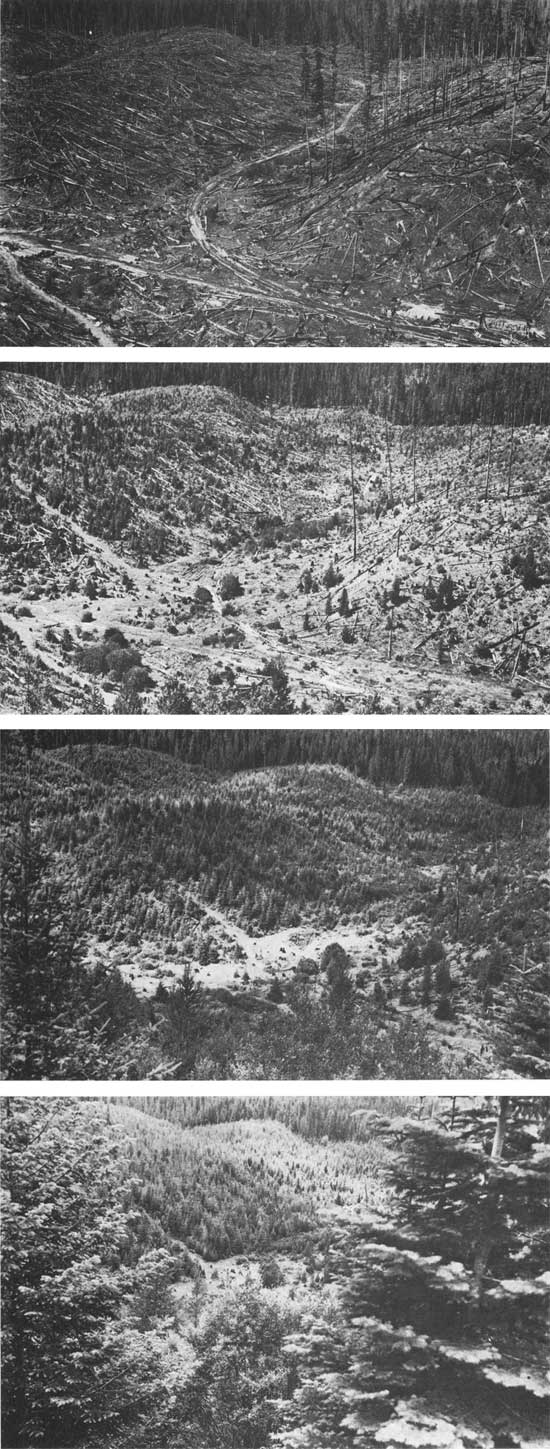

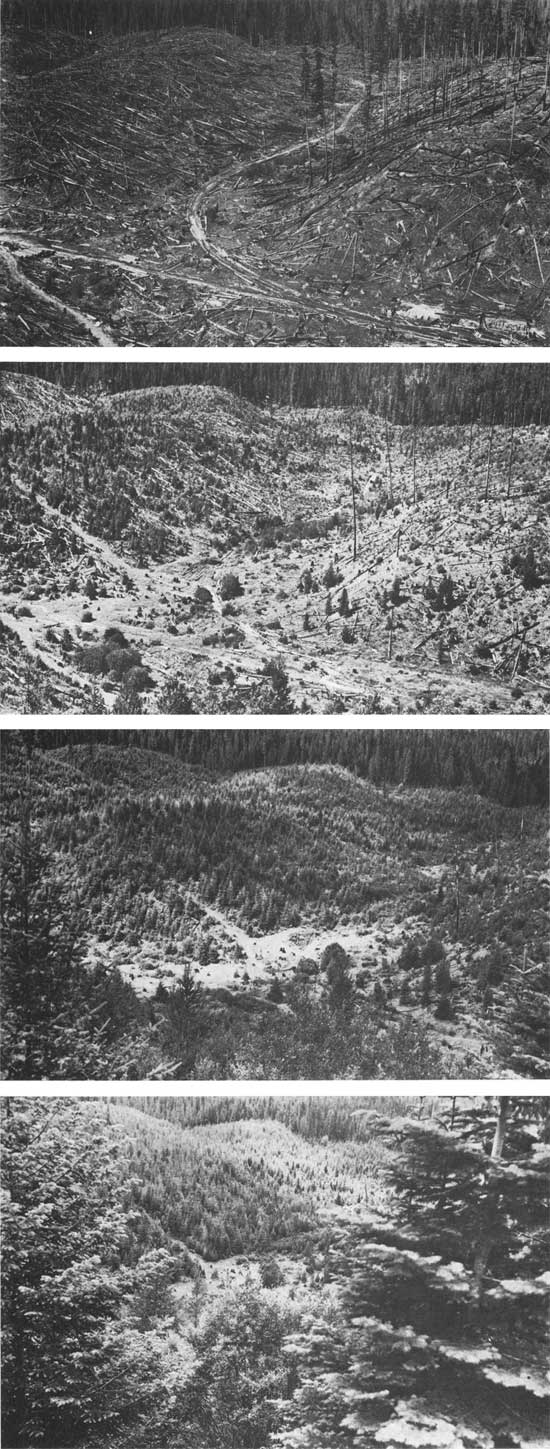

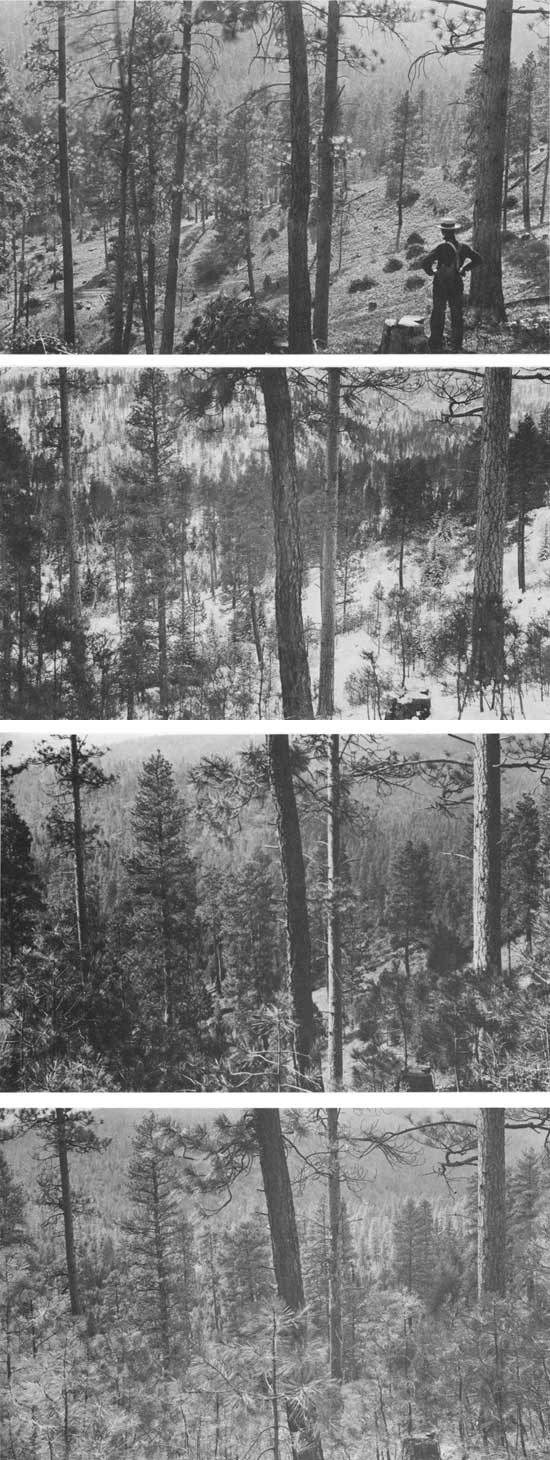

The most popular conception of the CCC was related to

its work in reforestation. The following photo sequence illustrates the

effectiveness of that particular phase of the CCC's contribution to

American forestry—the planting of trees. These photos also

illustrate that, with the proper attention, care, and protection,

forests can and do come back! (Area shown is within the former St. Joe

National Forest, now part of the Idaho Panhandle National Forests,

Idaho.) 1 (top). Logged in the early 1930's, acquired by the Forest

Service in 1938, and planted with western white pine trees by the CCC in

1939 and 1940 (1938 photo). (F—365171) 2 (2nd from top). Six

years later, the young trees are doing fine (1944).

(F—431541) 3 (2nd from bottom). After 11 years (1949).

(F—456363) 4 (bottom). After 16 years (1954).

(F—476579)

|

|

|

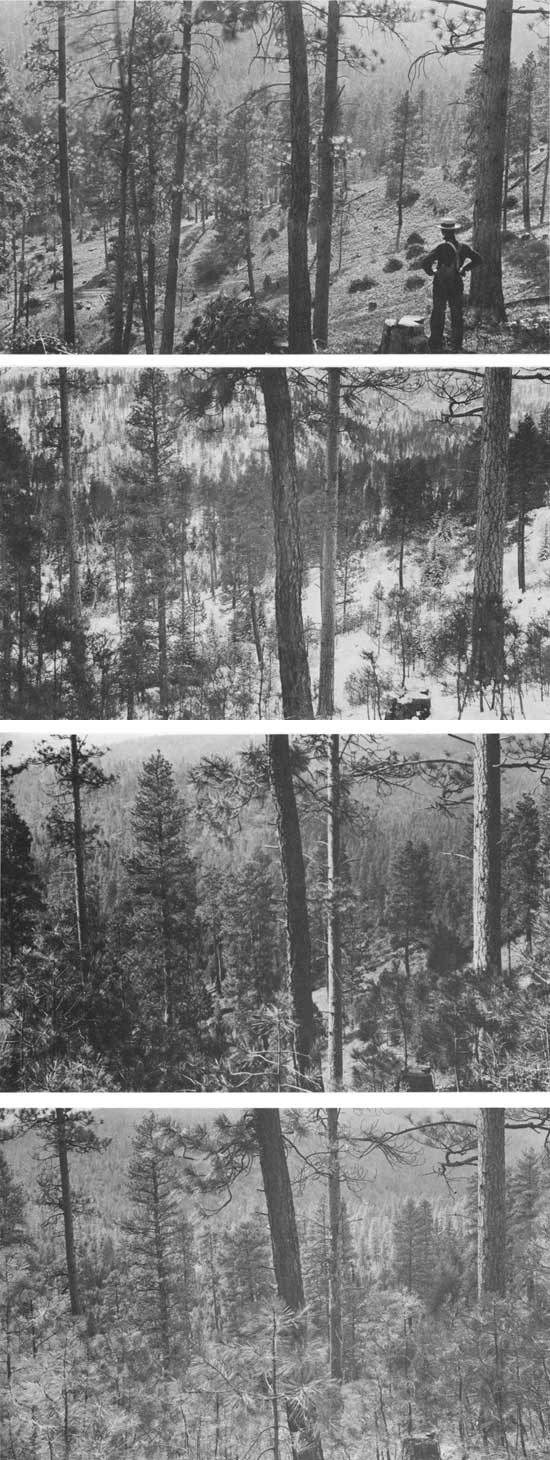

The leaving of seed trees is an alternative to planting

in reforestation work. This series of photos shows how seed trees

insured a future stand of timber on a cutover area on the Bitterroot

National Forest, Montana. 1 (top). Note the brush piled up for burning

in this cutover area (1909). (F—86475) 2 (2nd from top).

Reproduction on the area after 16 years (1925). (F—204813)

3 (2nd from bottom). And in 1927. (F—221277) 4 (bottom). And

the young timber in 1937. (F—354396)

|

"Civilizations have waxed and waned with their material

resources; dwindling means of livelihood have set rolling great tidal waves of

migration and have been a prolific cause of domestic disorder, class uprising,

and international war; but never before have the people of a great country still

rich in the foundations of prosperity sought to forestall future disaster by

applying a national policy of conservation—of which planned land use is the

central core."

Ferdinand A. Silcox (1933-1939)

|

|

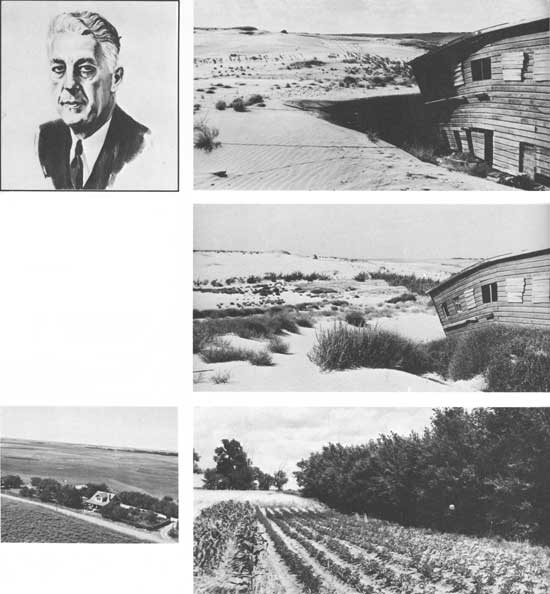

1 (top left). Ferdinand A. Silcox, Chief of the Forest

Service, 1933-1939. (Drawing by Rudolph Wendelin) The Prairie

States Forestry (Shelterbelt) Project, started by the Forest Service in

1935, proved to be an outstanding government-individual cooperative

effort of continuing effectiveness. 2 (bottom left). For Kansas farm

homes such as this one, extensive tree planting built a fine protective

barrier against the hot winds of the prairie. (F—404367) 3

(top right) & 4 (middle right). In one severe blow-sand area south

of Neligh, Nebraska, 52,000 cottonwood trees were planted in the spring

of 1938. (F—369779, F—386847) 5 (bottom right). In 8

years one Nebraska shelterbelt grew 35 feet high, affording prime

protection for the corn and potatoes on the north side of the belt.

(F—430576)

|

|

|

1. Shelterbelts planted in the spring of 1939 protected farms against

damaging north and west winds. In just 2 years the protection helped

this Kansas field produce an excellent crop of wheat (August 1941). (F—408931)

|

|

|

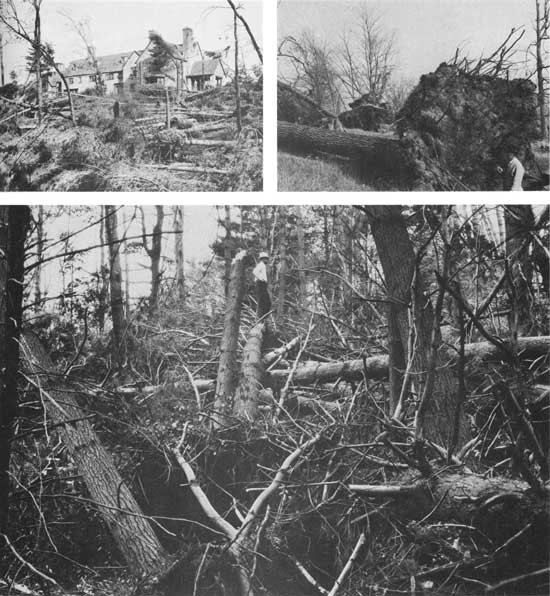

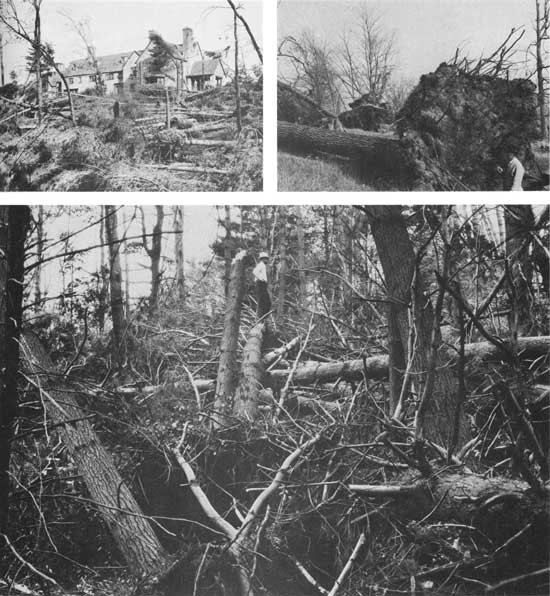

The Great New England Hurricane of September 1938 left a mark on the land,

not easily erased nor quickly restored. 1. The small lettering read:

"Please do not injure trees or other plants or scatter rubbish."

(Public picnic area near Petersham, Massachusetts.) (F—369798)

|

|

|

1 (top left). Totally destroyed were the large pine trees which once

shaded this lovely home near Petersham, Massachusetts. (F—373543) 2 (top right).

Following the hurricane, this maple orchard near Peacham, Vermont,

held little hope for high yields of maple syrup in 1939 and immediately

beyond. (F—369824) 3 (bottom). Farm woodlot owner in New Hampshire inspecting his

damaged timber to asses his loss. (F—373545)

|

|

|

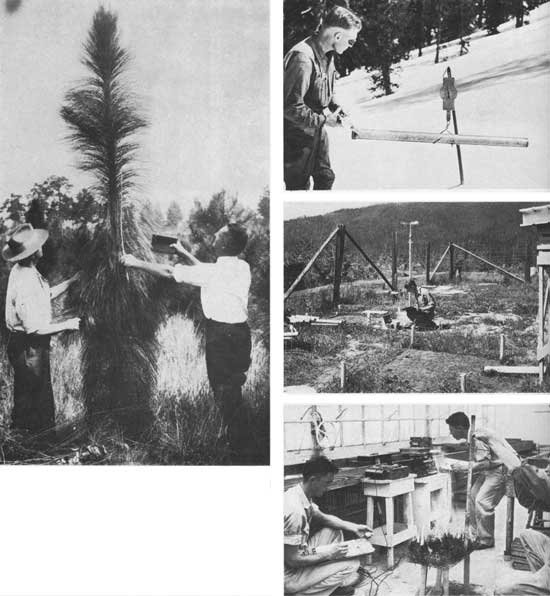

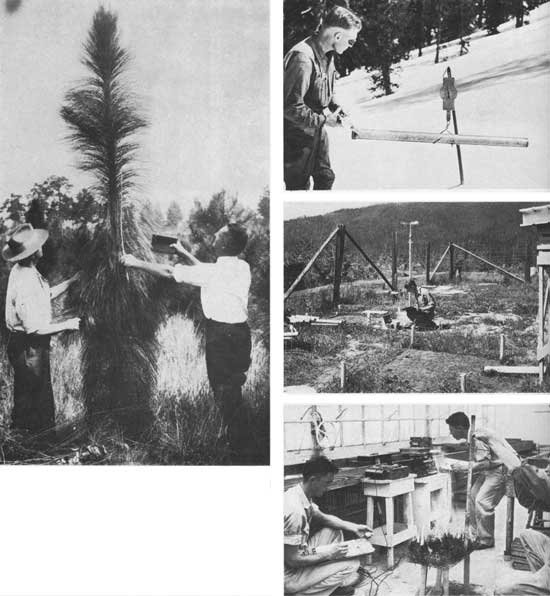

Forest Service research activities in field and laboratory began

a gradual transformation from generally basic studies to more

sophisticated experiments in resource management, protection,

and utilization. 1 (left). Discovery of this 7-year-old,

12-foot-high longleaf pine in an old field in South Carolina

in 1927 stimulated research on tree growth. Tree strains with

remarkably fast growth are now growing throughout the South,

as a result of this work. (F—218970) 2 (top right). Snow surveys have always

been an exceedingly important part of research, especially in the

mountain forest areas that are the source of water for the

agricultural and industrial valleys below. In 1930, this

particular project was undertaken by the Intermountain Forest and

Range Experiment Station, headquartered in Ogden, Utah. (F—249517) 3 (middle

right). Flammability of forest fuels (Idaho) (F—309734) and 4 (bottom right).

Fire behavior studies (Mississippi) occupied the scientists in

the 1930's no less than today, and they probably will for a long

time to come. (F—353532)

|

|

|

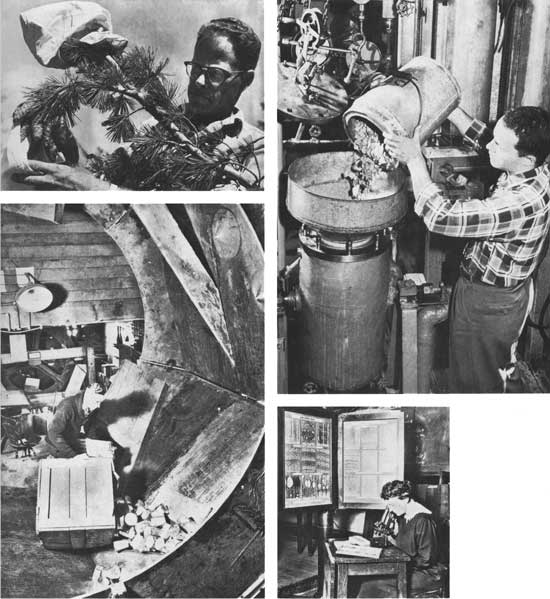

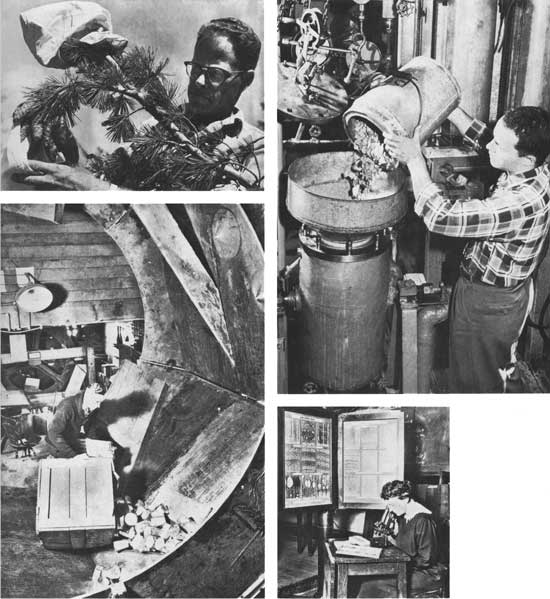

1 (top left). Fast growth is desirable, but good quality is even

more essential. An important study has involved controlled

pollination for improved growth and quality. Here, in 1959,

developing pine cones, following controlled pollination, were

protected from squirrels by canvas sacks. (F—493525) 2 (bottom left).

Box testing in the 1920's and the continuing development of such

testing machines proved helpful in solving World War II crating

and shipping problems. (F—162540) 3 (top right). Working with wood pulp

for better use of available tree species and for improved paper

products have occupied FPL scientists through the years. A

1925-1926 study involved a process especially suited to hardwoods. (Forest

Products Laboratory, M 100 959)

4 (bottom right). Wood species identification at the Forest

Products Laboratory (FPL), Madison, Wisconsin, 1921. (F—164888)

|

". . . scarcity of natural resources and

their control by the few may pave the way through widespread human

misery to despotism and dictatorship; while an abundance of natural

resources, accessbile to people generally, makes for democracy and

freedom.

Earle H. Clapp (1939-1943)

|

|

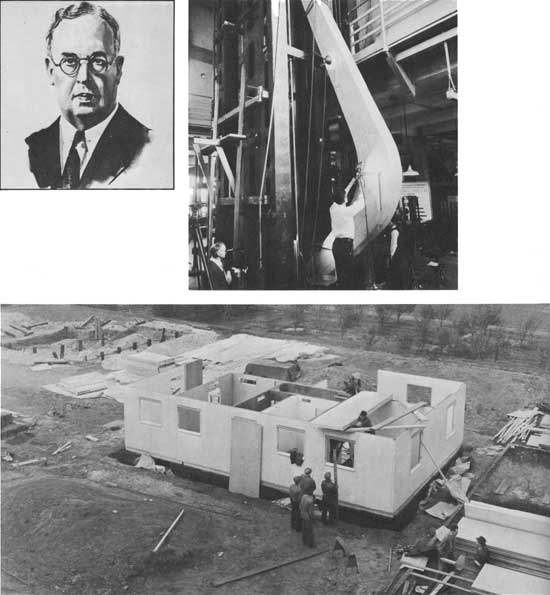

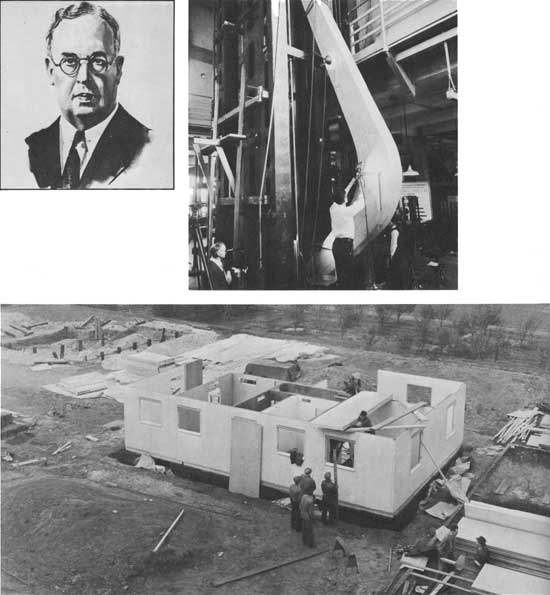

1 (top left). Earle H. Clapp, Chief of the Forest Service, 1939-1943. (Drawing

by Rudolph Wendelin)

2 (bottom). The first all-wood prefabricated house erected on FPL

grounds was built in 1937. (Forest Products Laboratory, M 324 20F) 3 (top right). In the middle 1930's,

FPL researchers developed the earliest glued-laminated arches made

in the United States. The arches had to undergo exhaustive tests

for durability and strength. They soon became widely used commercially. (Forest

Products Laboratory, M 251 88F)

|

|

|

1. In World War II, to make up for enemy-held sources of rubber, the

Forest Service supervised conversion of areas of the Salinas Valley,

California, to grow guayule, a desert shrub, for rubber production. (F—423981)

|

|

|

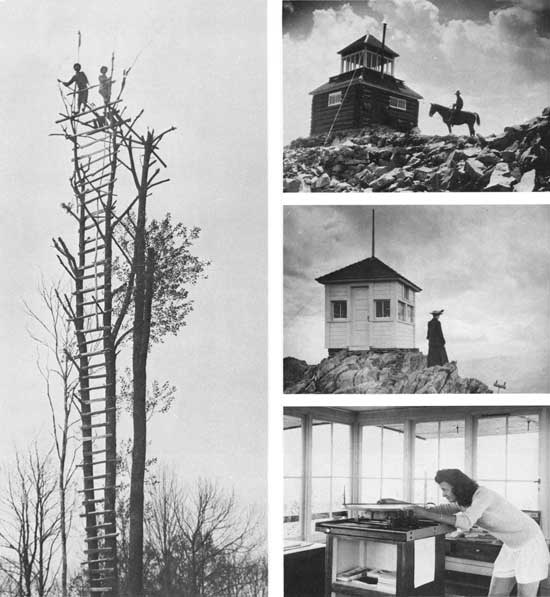

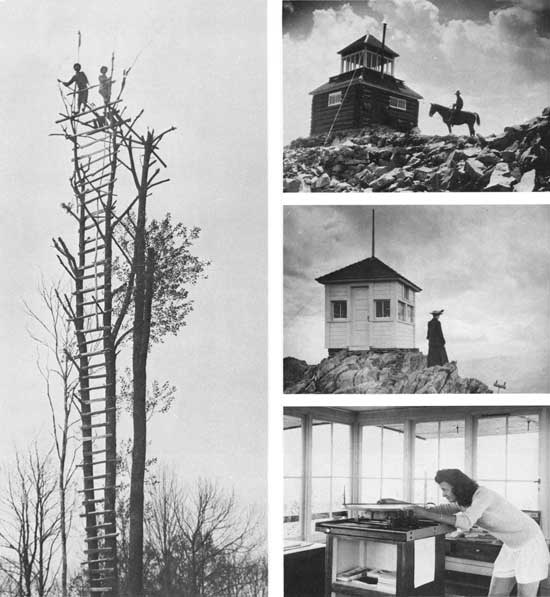

In forest fire detection and the control of wild fires, there was also

dramatic evidence of "growing up." 1 (left). Lookout tree on Turkey

Knob, West Virginia, 1919. (F—40806A) 2 (top right). Fire lookout on Payette National

Forest, Idaho, 1930. (F—253466) 3 (middle right). Twin Sisters Fire Lookout on the

Colorado (now Arapaho-Roosevelt) National Forest, 1917. (F—35806A) 4 (bottom

right). And Spruce Mountain Lookout, Medicine Bow National Forest,

1943. (F—426381)

|

|

|

1 (top left). Almost a quarter of a century passed between the start

of a pony blimp fire patrol of the Angeles National Forest, California,

September 1921. (F—156936) 2 (top right). And fire detection by plane of the

Superior National Forest in Minnesota, September 1945. (F—436422) 3 (bottom).

The 1924 San Gabriel Fire on the Angeles National Forest, California

(Mt. Wilson Observatory in the foreground). (F—194433)

|

|

|

1. Fires in the western forests can be very spectacular and are

tough to control, especially in dry weather. They often make the

headlines. This was the Malibu Fire of 1935 on the Angeles National

Forest, California. (F—342637)

|

|

|

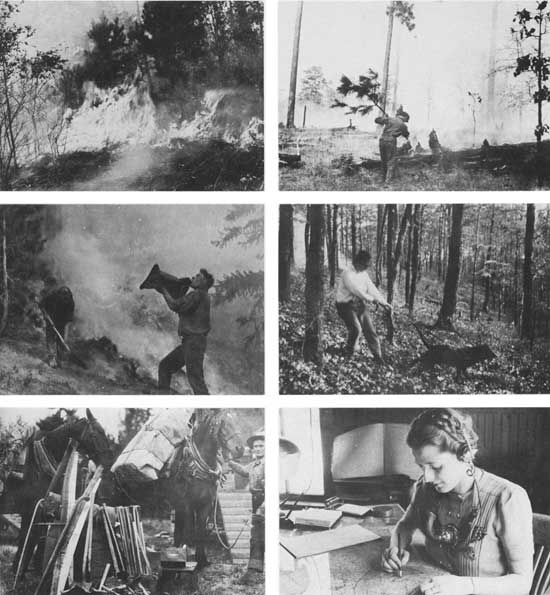

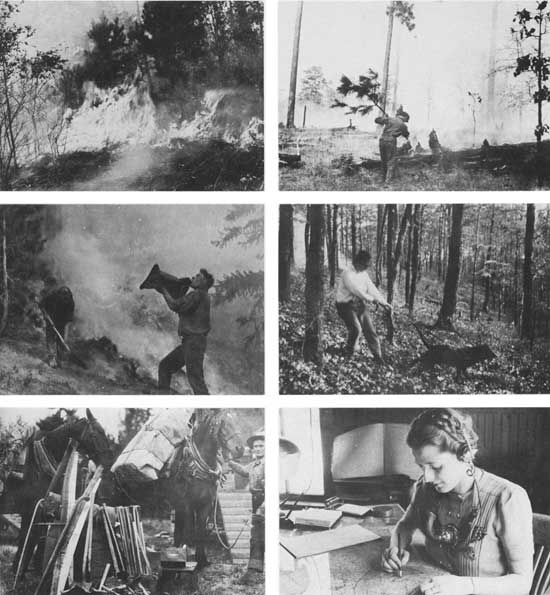

1 (top left). Less dramatic, generally, are the wildfires in our

Eastern and Southern States, but in larger numbers, they have caused

great damage through the years. This fire was in a shortleaf pine

stand in Mississippi, 1933. To light the fire . . . (F—428698) 2 (middle left).

Shovels and a blessed drink of water (Washington 1919). (F—44482A) 3 (bottom

left). Horsepower and axes, saws, shovels, and other equipment

(Montana 1932). (F—266919) 4 (top right). The limb of a tree (Louisiana 1917). (F—36684A)

5 (middle right). A bloodhound to track down the fire-setter

(Arkansas 1930). (F—246334) 6 (bottom right). A cool head, calm manner,

and dispatching skill (Montana 1941). (F—422297)

|

|

|

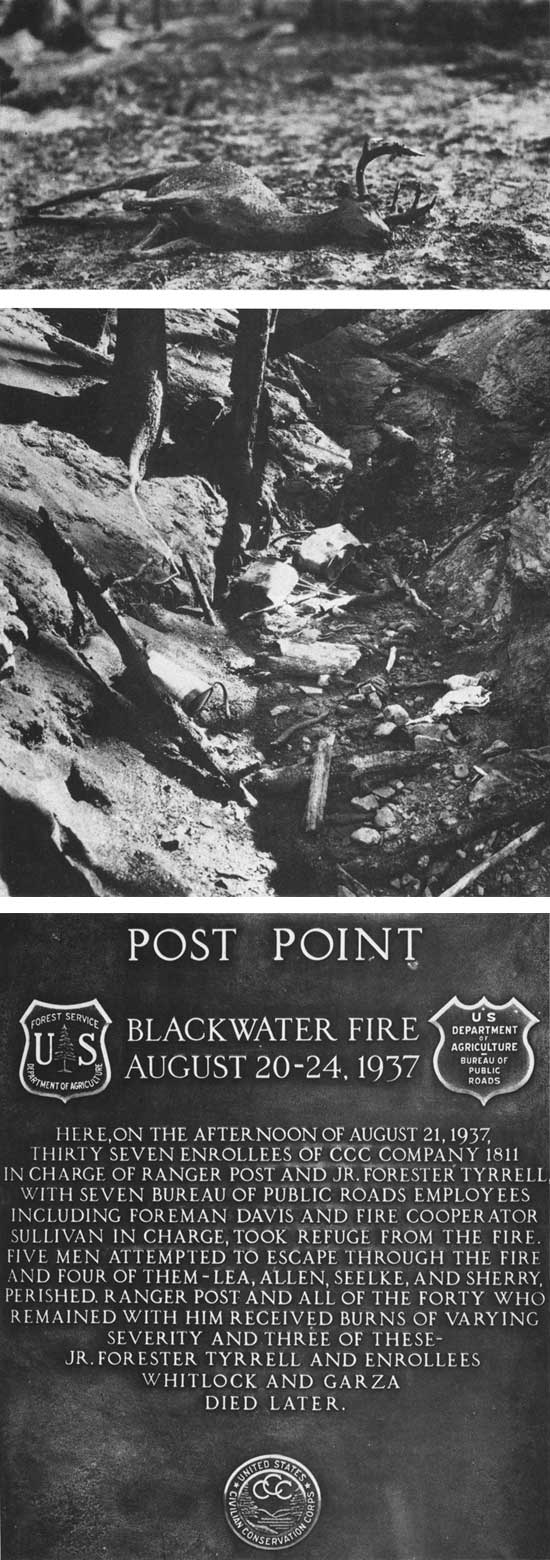

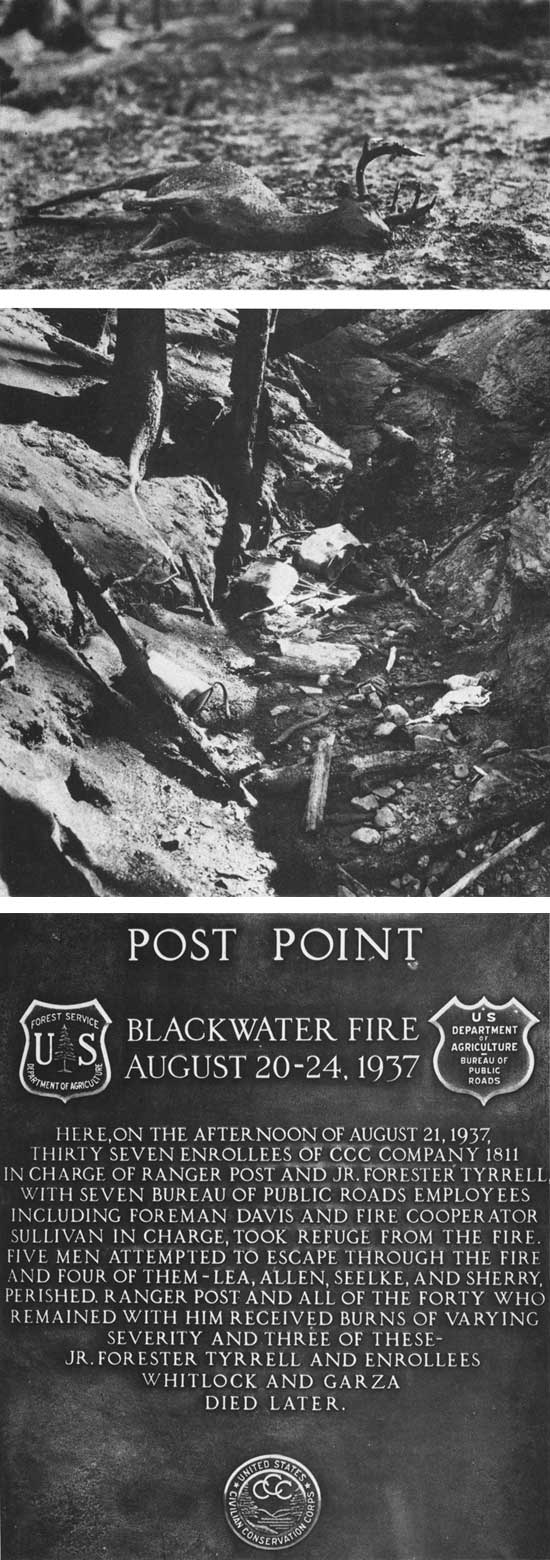

Forest fires can kill more than trees . . . 1 (top). Wildlife. (F—260971)

2 (middle) & 3 (bottom). People, too. Seven men died at this spot during the

Blackwater Fire in the Shoshone National Forest (Wyoming, August

1937). (F—351524, F—424745)

|

|

|

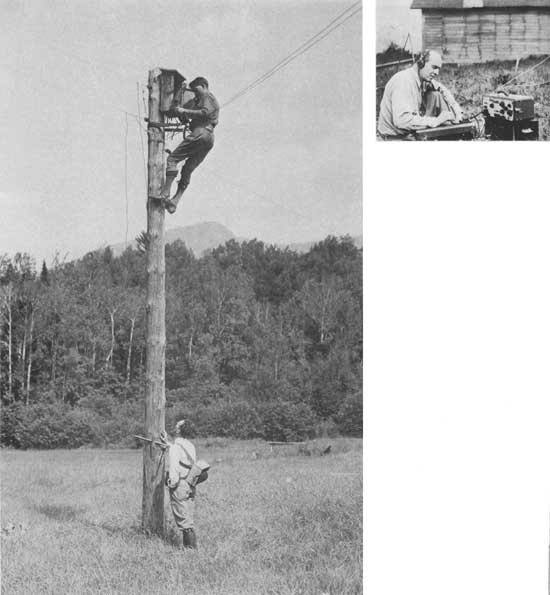

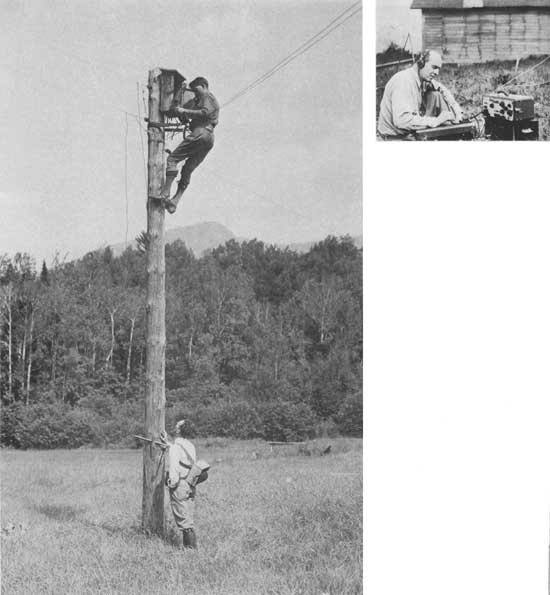

1 (left). The Forest Service had graduated to metallic (two lines)

telephone communication by 1926 on the White Mountain National Forest,

New Hampshire. (F—212185) 2 (top right). Portable radios were in wide use

throughout the Service by the 1930's. (F—249319)

|

|

|

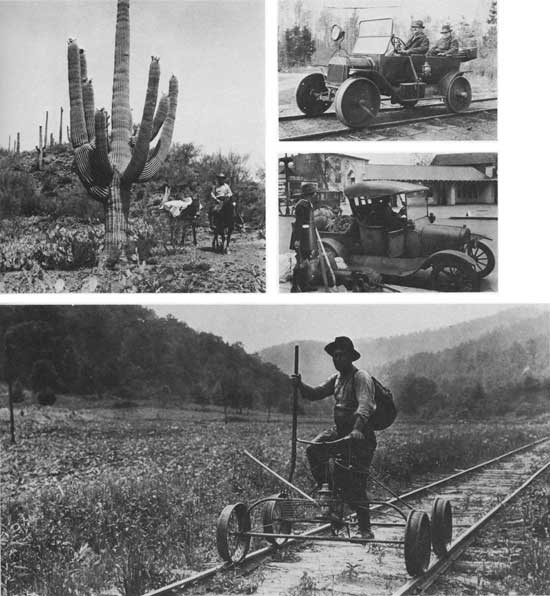

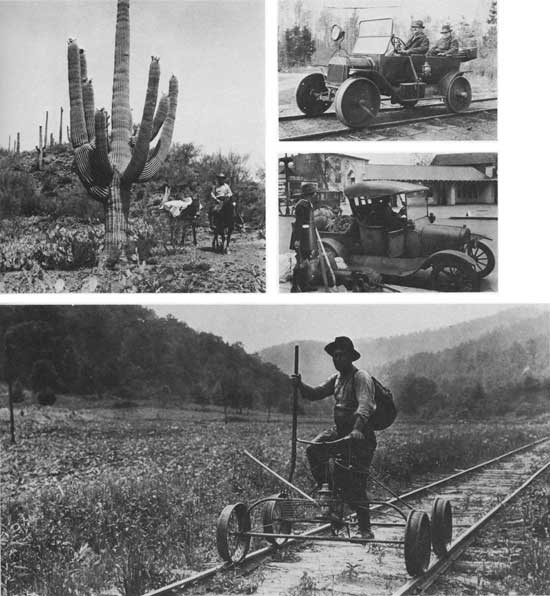

1 (top left). Horse power—Supervisor Kirby used the traditional

pack outfit for his 1939 travels on the Tonto National Forest,

Arizona. (F—380239) 2 (top right). This is how Virginia & Rainy Lake Co.

General Superintendent Gilmore and Forest Service District Two Fire

Protection Officer John McLaren made their way, in 1917, using the

company's logging railroad (Superior National Forest, Minnesota). (F—33749A)

3 (middle right). Helen Dowe didn't spare the equipment as she

started on a 1921 surveying trip into the Montezuma National Forest

(now part of Grand Mesa-Uncompahgre and San Juan National Forests,

Colorado.) (F—153253) 4 (bottom). Leg power—Forest Guard Perry Davis

making his rounds on the Pisgah National Forest (North Carolina

1923). (F—176440)

|

|

|

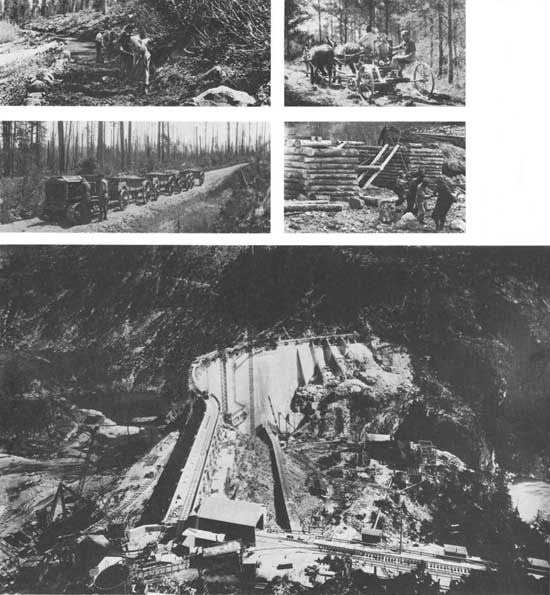

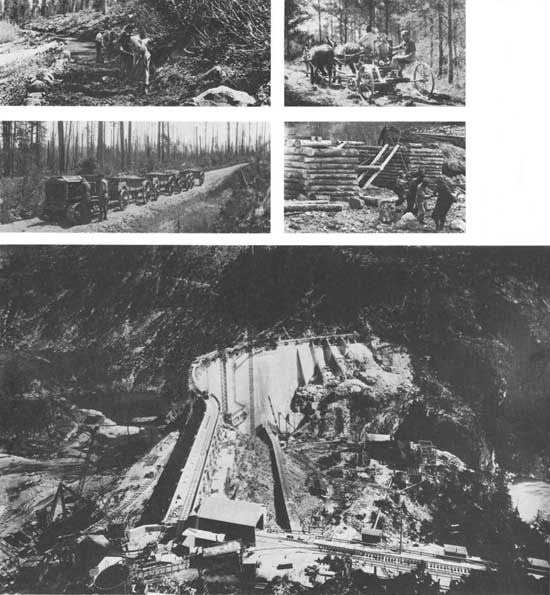

Roadbuilding in the 1920's: 1 (top left). California, 1921. (F—158959) 2 (middle

left). Kaniksu National Forest (now part of the Idaho Panhandle National

Forests), 1921. (F—158593) 3 (top right). Minnesota (now Chippewa) National

Forest, 1922. (F—166802) 4 (middle right). Building a pier for a 3-span bridge

on the Colorado (now Arapaho-Roosevelt) National Forest, 1920. (F—45780A)

5 (bottom). The Diablo Dam on the Skagit River was under construction

in September 1930. Diablo Lake is on the Mt. Baker National Forest,

Washington. (F—249303)

|

|

|

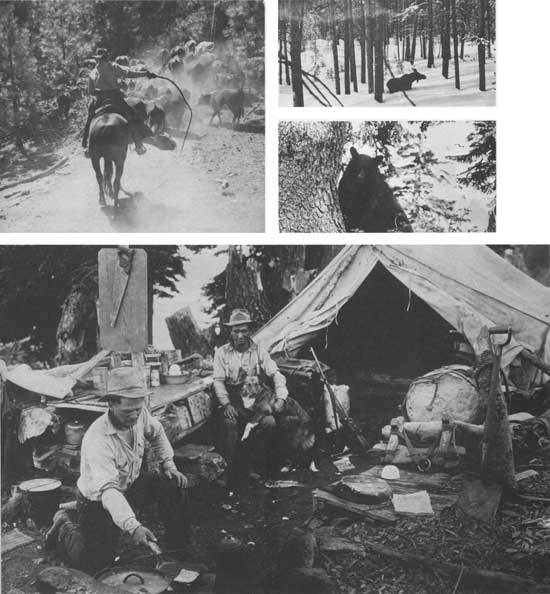

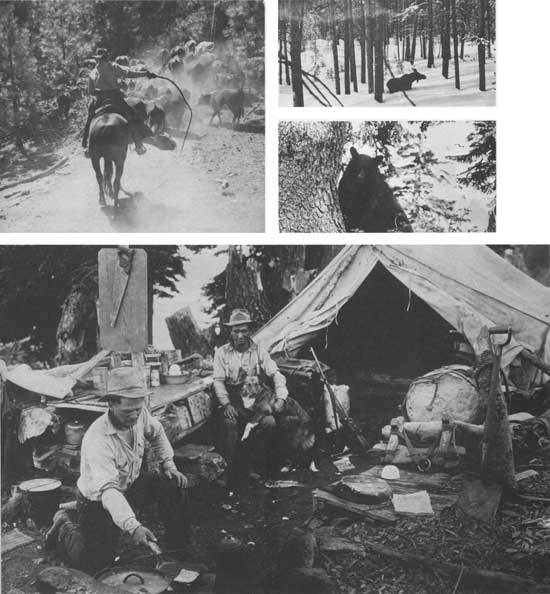

Enough food to go around . . . 1 (top left). After spending the summer

grazing in the National Forest, the cattle were driven back to the ranch

in the fall (Sequoia National Forest, California, 1941). (F—436179) 2 (top right).

After shedding his horns, the bull moose made his way without difficulty

through 3-1/2 feet of snow. (Absaroka National Forest, now part of the

Lewis & Clark and Gallatin National Forests, Montana, March 1923). (F—177158)

3 (middle right). A classic shot of Mr. Black Bear (Mt. Baker National

Forest, Washington, 1929). (F—252335) 4 (bottom). In this sheepherder's camp, the

packer did the cooking (Snoqualmie National Forest, Washington, 1930). (F—252315)

|

|

|

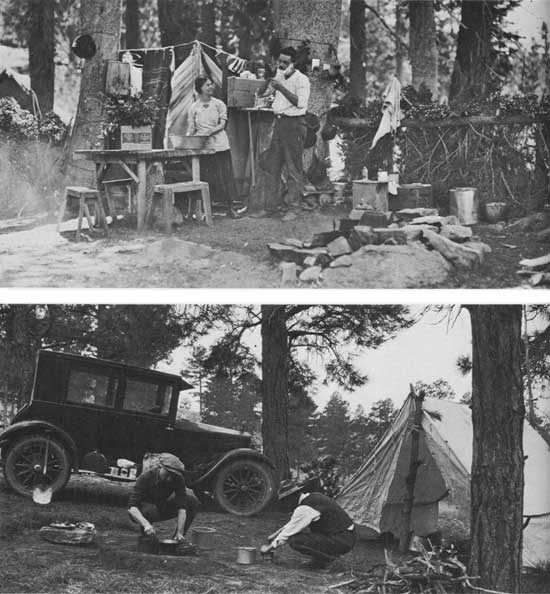

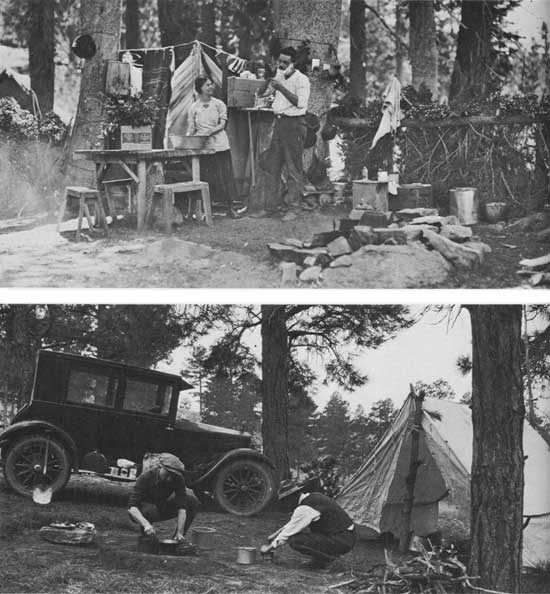

Recreation—camping has always been popular. 1 (top). Cleveland

National Forest, California, 1922. (F—164475) 2 (bottom). Cibola National Forest,

New Mexico, 1924. (F—185858)

|

|

|

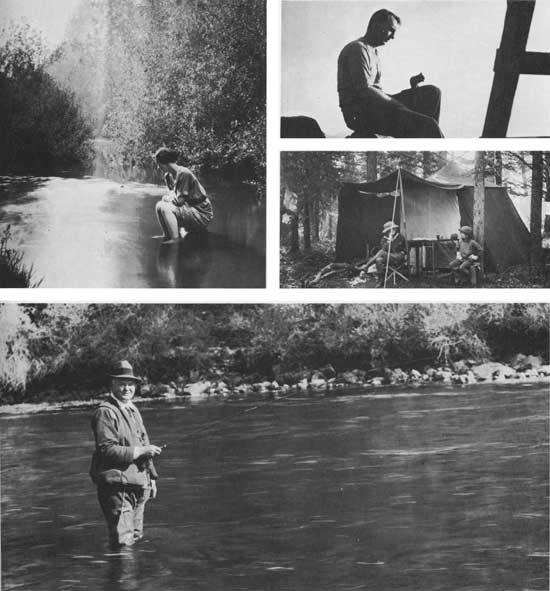

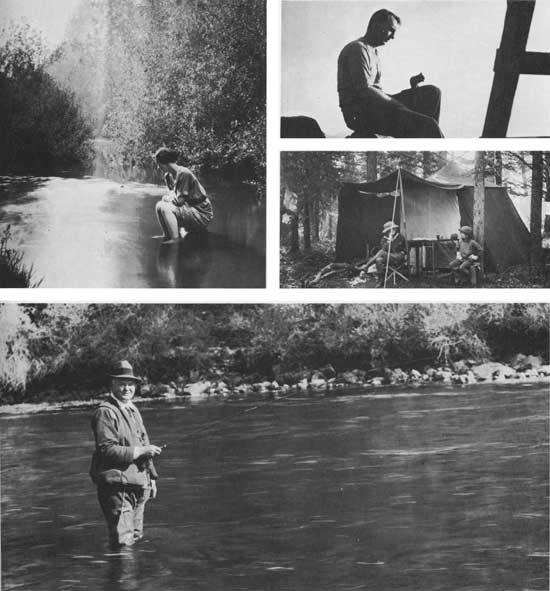

1 (top left). Deschutes National Forest, Oregon, September 1922. (F—174150)

2 (top right). Good friend. Whitman (now Wallowa-Whitman) National

Forest, Oregon, July 1924. (F—188852) 3 (middle right). Pike National Forest,

Colorado, 1923. (F—179895) 4 (bottom). Steelhead trout lured former President

Herbert Hoover to the Klamath National Forest, California, in 1933. (Forest Service No.

95—G—285193, in the National Archives)

|

|

|

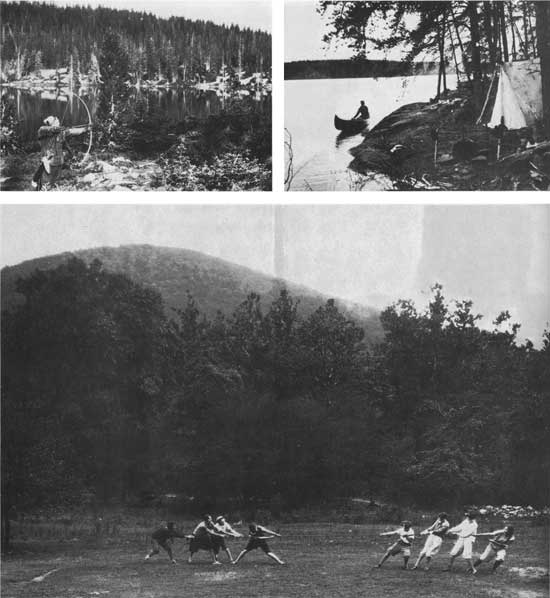

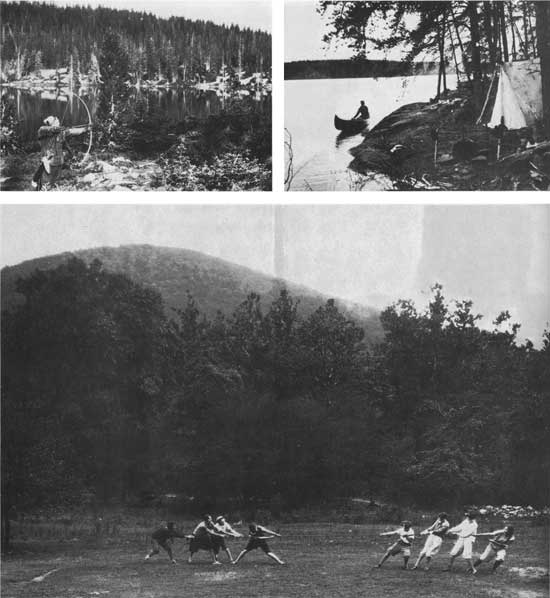

1 (top left). Wasatch National Forest, Utah, 1930. (F—253259) 2 (top right).

Superior National Forest, Minnesota, 1921. (F—152987) 3 (bottom). Shenandoah

(now George Washington) National Forest, 1925. (F—202571)

|

|

|

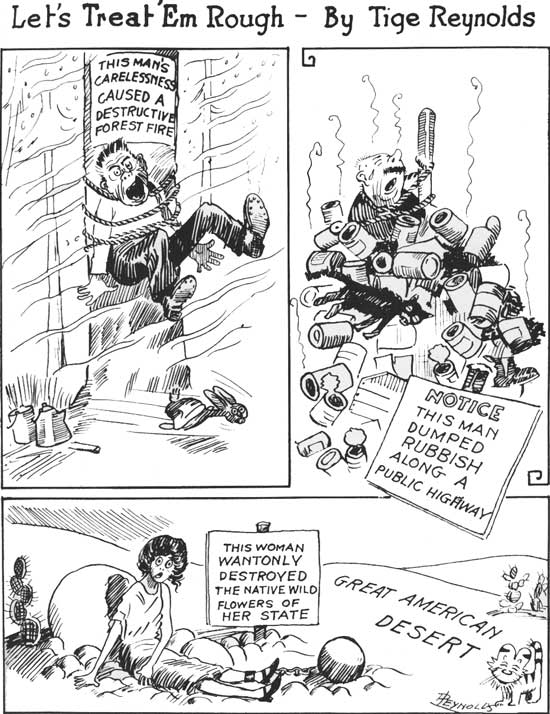

1. From the Tacoma, Washington, Daily Ledger, March 18, 1923. (F—175456)

|

|

|

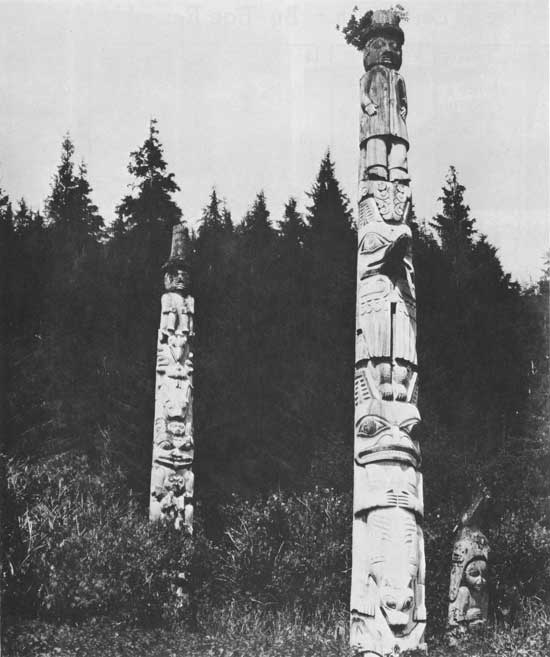

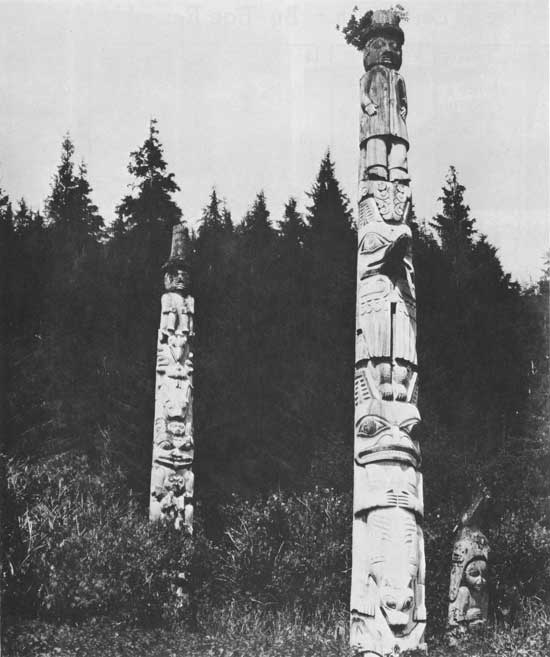

1. Alaska—land of totem poles . . . (F—253912)

|

|

|

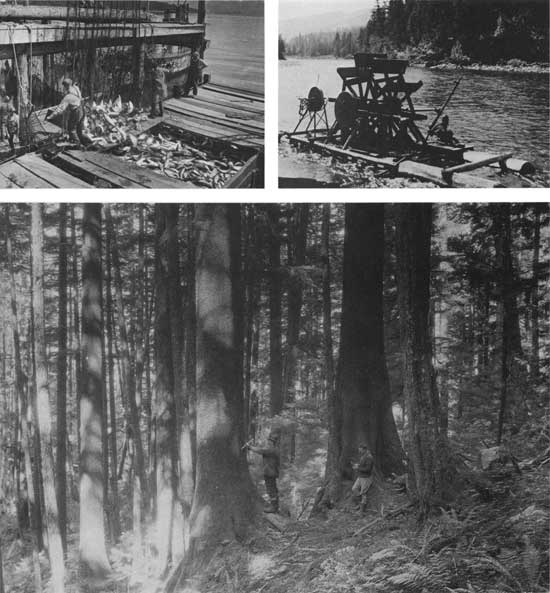

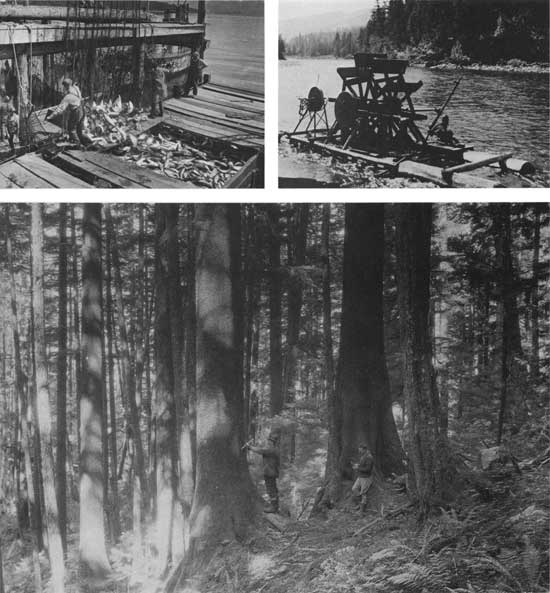

1 (top left). Alaska—land of salmon . . . (F—253239) 2 (bottom). Timber . . .

In 1930, Forest Ranger J. M. Wyckoff and Regional Forester B. F.

Heintzleman. (F—253186) 3 (top right). This ingenious waterwheel was used in

1926 on the Flathead National Forest, Montana, to pump water and operate

a grindstone. (F—213200)

|

|

|

Interesting people, places, and posters . . . 1 (top). Iowa State

University forestry students camped with Professor Jeffers in the

Arapaho National Forest, Colorado, in 1923. (F—179928) 2 (middle left). A hot

time out in the Umpqua National Forest, Oregon, September 1930. (F—251074)

3 (bottom left). Former Chief Forester, Col. William B. Greeley

joined 4-H Club members in a special Washington, D.C., tree planting

project in 1932. (F—265944) 4 (middle right). Young man with a whistle on

a sunny day in 1919, in the village of Kake, Alaska (Tongass

National Forest). (F—179246) 5 (bottom right). At the 1917 National Farm and

Livestock Show in New Orleans, Louisiana. Aviatrix Ruth Law found

the Forest Service exhibit of special interest. (F—36172A)

|

|

|

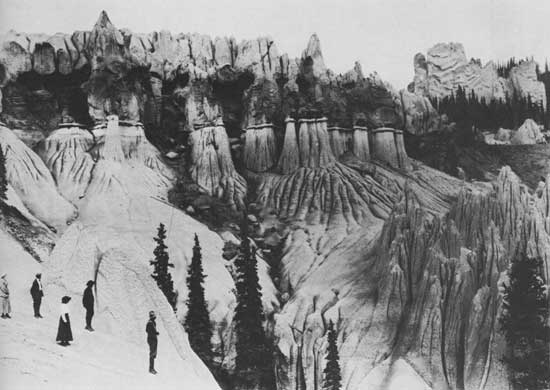

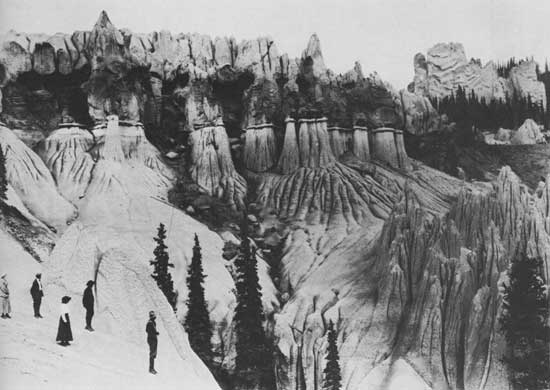

1. Tourists viewing an interesting rock formation in the Rio Grande

National Forest, Colorado, in 1917. (F—95—G—29260A in the

National Archives)

|

|

|

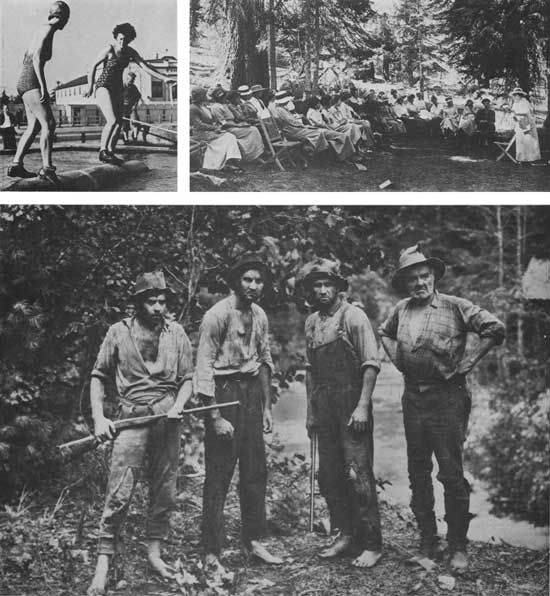

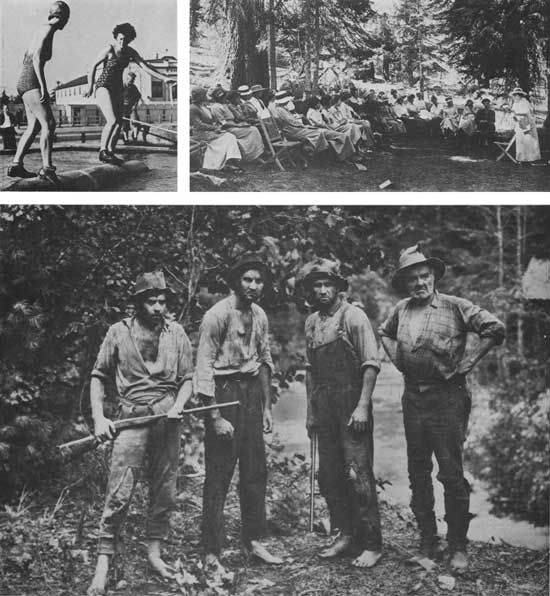

1 (top left). The 1938 Women's Logrolling Championship competition

at Bloomer, Wisconsin. (American Forestry Association) 2 (top right). The Sierra National Forest,

California, served as an outdoor laboratory for students of the

Fresno Normal School in 1923. (F—172730) 3 (bottom). When the Forest Service

photographer "shot" these hardy mountain men in 1922, somewhere on

or close by the Cherokee National Forest in Tennessee, he had no

way of knowing this photograph would turn out to be the alltime

pinup favorite in Forest Service offices. Or did he? (F—518655)

|

|

|

1. Forest resident and staunch cooperator, Chief Little White Cloud

is shown in August 1940 on Star Island in Cass Lake, Minnesota, on

the Chippewa National Forest. (F—401133)

|

|

|

1. In 1926, the Forest Service "Showboat" stopped at Mount Lebanon

School in the Cherokee National Forest (now part of the

Chattahoochee National Forest, Georgia) to show slides and present

forest fire protection materials. The school was within the old Blue

Ridge Ranger District of Forest Ranger Arthur Woody, shown with

arm pointing to oldstyle poster over the door. Ranger Woody,

a colorful individual and a legend in his lifetime and since,

typified many of the early-day forest rangers. They were the Forest

Service's "self made" and dedicated pioneers, guardians of the public

forests, meriting the respect and appreciation of their fellow workers

and forest users alike. (F—204272)

|

|

|

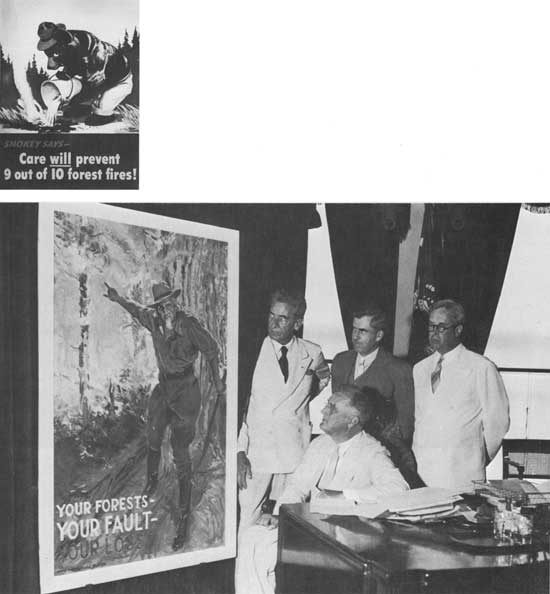

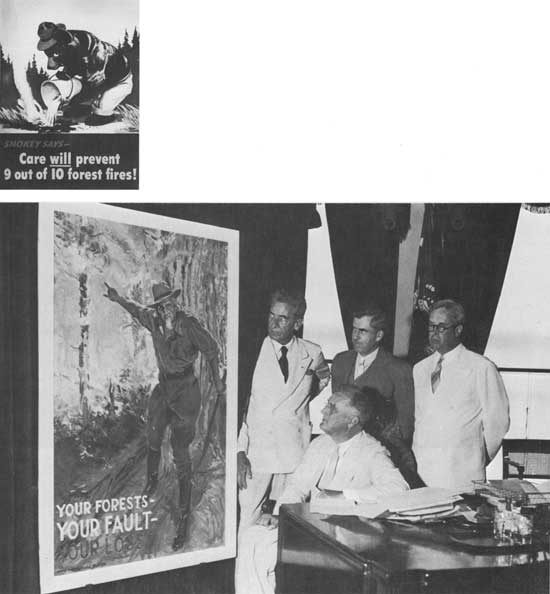

1 (top left). Toward the end of the "growing up" period, Smokey

Bear came into being as the nationwide symbol of forest fire

prevention. This was the first Smokey Bear poster, issued in

1945 as part of a continuing Federal-State cooperative effort with

the sponsorship of the Advertising Council, Inc. Purpose: to

reduce the number of forest and range fires caused by carelessness. (Forest

Service Cooperative Fire Protection)

2 (bottom). Artist James Montgomery Flagg helped the national

forest fire prevention cause with his famous "Uncle Sam" painting

in 1937. With Mr. Flagg (left) and President Franklin D. Roosevelt

(seated), who accepted the original work, were Secretary of

Agriculture Henry A. Wallace and Associate Chief Forester Earle H.

Clapp. (F—356947)

|

aib-402/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 12-May-2008

|