|

National Forests of Wyoming Miscellaneous Circular No. 82 |

|

NATIONAL FORESTS OF WYOMING

SOUTHERN WYOMING

MEDICINE BOW NATIONAL FOREST

In the extreme south, about midway between Nebraska and Utah, is the Medicine Bow National Forest. Long before the Oregon Trail was blazed through Wyoming, "Medicine Bow" was the scene of the red man's annual bow-making festival. From this gathering, according to one legend, comes the name which has attached itself to landmarks for miles around. Here the braves from many quarters came together to cut mountain mahogany, which grows in great abundance along the streams in these hills and was highly prized throughout the region for bowwood. Here the Indian found also a species of pine tree growing in even, dense stands, and growing straight and tall and very trim. Where it was overcrowded it was small—just right for tepee poles. So he called it lodgepole pine. It filled an important place in his domestic economy. To-day the white man cuts from the same forests saw logs and railroad ties—less romantic perhaps but no less important than bows and lodge poles.

Ever Since the region was first settled by the white man Medicine Bow timber products have been in demand throughout southern Wyoming. The rails of the Union Pacific which led to the point where the golden spike marked the final link in our first transcontinental railroad were underlaid with Medicine Bow railroad ties, and to-day, for miles each way from Laramie, the forest headquarters, the tracks are laid on Medicine Bow ties. In addition to supplying employment for many men in the woods, the ties from the Medicine Bow National Forest keep in operation a large treating plant in Laramie. Mine props and timbers from the region are important throughout a wide territory. And while the lumber, railroad ties, and mine timbers from the Medicine Bow Forest are fitting into the general scheme of things miles from their point of origin the national forest itself is untiringly building up, layer by layer, new supplies of wood and providing for those near by, and for many others who visit it every year, the benefit of invigorating coolness and inspiring scenery.

|

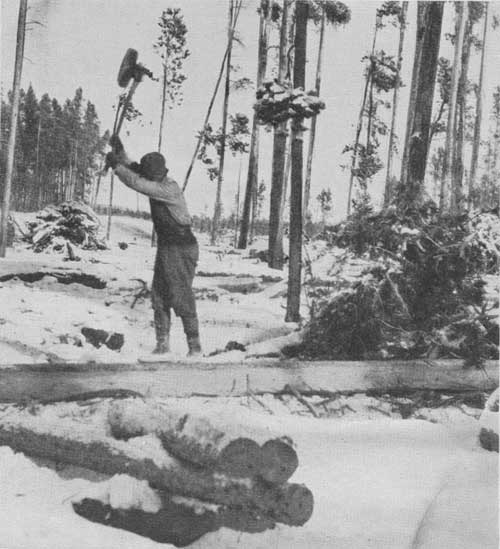

| FIG. 1.—A tie hack hewing a railroad tie in the Medicine Bow National Forest. (F-39695-A) |

Fort Collins, Colo., and Laramie, Medicine Bow, and Saratoga, Wyo., are all entrances to the Medicine Bow National Forest.

Thirty-three miles west of Laramie is the forest boundary, just above the old mining town of Centennial, and 12 miles farther on is the foot of Medicine Bow Peak. From here a foot trail 2-1/2 miles long goes up to the fire lookout station on top. The lookout station gives a commanding view of the whole forest area of over half a million acres, and the lookout guard's knowledge of the surrounding country will help in picking out the important points within view and in understanding the significance of the activities on the forest.

Immediately at the foot of Medicine Bow Peak are signs of old burns, but they are small and are soon lost in the continuous expanse of deep green, unscarred forest, which stretches away in every direction. Below, over to the west, the solid canopy of the forest is broken by a fold that grows constantly deeper and deeper until in the dim distance it flattens out and merges imperceptibly into the surrounding greenness. This fold is North French Creek, thickly timbered all the way to the forest boundary. A little to the left is South French Creek, and around to the south are the many branches of Douglas Creek, the upper courses of which are marked by gentle depressions in the rich green carpet that extends on and on across the line into Colorado as far as the eye can reach. Ties cut on Douglas Creek are floated down to the North Platte River and then down the river to Fort Steele, where they are landed and shipped to Laramie for preservative treatment and distribution. The experienced eye of the lookout guard picks out a hill many miles due south as a point that marks the location of Foxpark, where most of the tie operations are concentrated. Ties are shipped from there to Laramie over the Laramie, North Park & Western Railroad.

Most of the ties produced on the Medicine Bow are hewn out by hand. Because of the small diameter and slight taper of the typical lodgepole pine (see p. 2) ties can be made by merely slabbing two sides of the tree, peeling the rest, and then cutting it into 8-foot lengths. Woods workers skilled in the use of the broadax can hew "faces" which for smoothness might have been planed. And they work with speed too, turning out regularly 25 to 30 ties a day.

In sales of lodgepole pine for ties on the Medicine Bow Forest, trees too large or to rough for tie making are sawed into lumber. In some instances very small portable mills replace the chopper in making ties. This is the case chiefly where the stands are exceedingly scattered or are made up of trees which, because of form, are not suitable for hewing.

East of Medicine Bow Peak lies Laramie, and beyond, across the plains, is a ridge, hazy because of its distance from the lookout tower. It is the Pole Mountain Military Reservation, recently added to the Medicine Bow National Forest for peace-time administration as a forest unit. It is also a Federal game refuge, like Sheep Mountain, between Medicine Bow Peak and Laramie.

After a complete survey of the forest from the vantage point of the lookout tower on Medicine Bow Peak we are not surprised at the statement that the whole stand of timber on the forest is estimated at more than 4,000,000,000 board feet. This is an imposing figure, so imposing that it is not easy to grasp its significance. The lookout guard makes it easier by telling us that this stand of timber is capable of producing more than 2,000,000 railroad ties every year, perpetually, or half again as many as are needed for annual replacements on the Union Pacific Railroad. From this amount of wood, 4,000 modern frame bungalows could be built. It is worth $10,000,000 on the stump.

FIRE PREVENTION

"It will burn, too, if we give it a chance. My job," says the lookout man, "is to see and report smokes that indicate fire. Knowing the country, I can locate them pretty closely—better than if I had to depend on map and fire finder alone. Rangers are always on a hair trigger for fire during the dry season. It is important to know where the mills, camps, and railroad tracks are, in order to avoid false alarms. This is especially worth while, for it takes more time to make a run in the timber than it does in town. A good telephone system insures quick communication, and a large force of volunteer cooperators guarantees protection for nearly every acre. Our cooperators fill a place no salaried organization could fill. Of course they are paid for the time actually spent on fires."

For every ranger district there is a fire-fighting organization, which functions in much the same way as a volunteer fire department in a small town. The details of this organization are fully set forth on the fire-organization chart, posted by the telephone in every ranger station. On the chart is a list of the cooperators; each assigned the rôle for which he is best fitted—foreman, truckman, cook, axman. Each one knows his place, his responsibility, and his rate of pay. In every community there are a few men designated as keyman, who take the responsibility of receiving fire reports in the ranger's absence and of organizing crews and handling fires until relieved by some forest officer. The general public may not realize what the faithful work of these men means, but many a serious disaster has been averted by their timely action. The carelessness of the tourist or camper seems doubly contemptible in comparison with these heroic efforts.

Caches of fire tools are kept at ranger stations, at settlements, and in the conspicuous red boxes along the roads and trails, always ready for use at a moment's notice.

Every member of the forest force spends a great deal of time in perfecting fire-fighting plans and the fire-fighting organization, and in keeping tools and equipment in first-class shape for immediate use. In addition to reducing fire hazard through educational work, they take the initiative in fire-hazard studies and in the construction of fire-prevention improvements, which include a large mileage of telephone lines and trails.

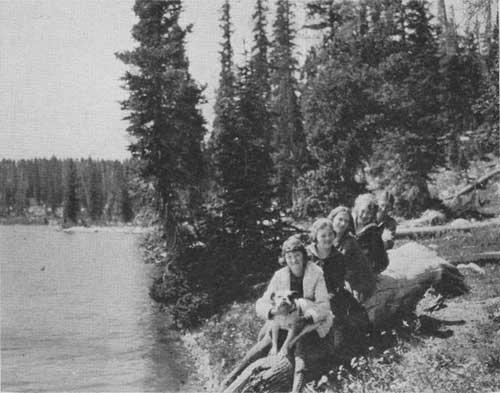

Scattered about the forest are many summer cabins and camps. The cool nights and bright, warm days of summer in the Snowy Range draw many visitors who like to fish and hike and be out-of-doors. The unusual accessibility of this range, together with its resorts and near-by ranches, makes it a popular summer place. During the summer there are also many men in the forest tending herds of cattle and sheep.

Other activities on the Medicine Bow Forest are just as interesting as those here discussed. In fact, all the activities described later in connection with the other forests of the State could also be found on the "Bow." Each of the other forests, however, may best be seen through some line of work which is especially important there, though, of course, it must be remembered that each forest has a variety of resources and uses.

|

| FIG. 2.—Camp Fire Girls at Brooklyn Lake, Medicine Bow National Forest (F-50356-A) |

HAYDEN NATIONAL FOREST

Also in southern Wyoming, across the upper North Platte Valley to the west of the Medicine Bow National Forest, is the Hayden National Forest. The Sierra Madre Mountains of the Hayden are the northernmost extension of the mountainous Continental Divide in Colorado. At the northern boundary of the Hayden Forest, the Sierra Madres slope gently down into the broad, level plain of the Great Divide Basin, where accurate surveying instruments are required to find the exact line between Atlantic and Pacific slopes.

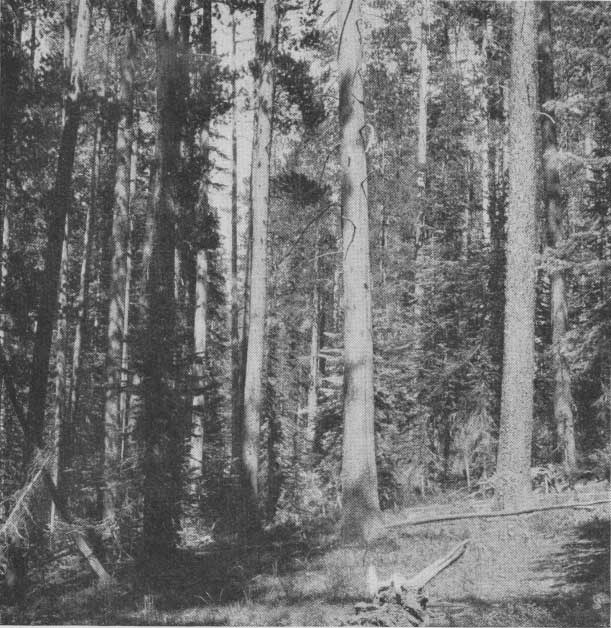

The Hayden covers about 400,000 acres, a little of it in Colorado. There are some fine stands of lodgepole pine and Engelmann spruce in the upper (south) end. A great deal of this region, which makes up the Encampment and Big Creek watersheds, was cut over very heavily for ties and lumber before the establishment of the old Sierra Madre Reserve (as the Hayden was first called), but on much of it a very thrifty second growth which promises rich yields in the future is now coming in. Extensive uncut areas show the quality of the original stands and constitute a resource of impressive proportions. Some really distinctive recreation areas are found here. A part of their distinctiveness consists in the fact that many of their attractive lakes and streams are hidden away and are at the disposal of only the few who like horseback travel and hiking. Battle Lake, however, is accessible to motorists.

From this high, rugged section the forest slopes down gradually toward the west and northwest into a less mountainous type of country. On the map of this part of the forest are shown such towns as Copperton, Rambler, and Battle, which are now only the ghosts of earlier settlements once prosperous and busy, when the discovery of rich copper-ore deposits introduced this region to the world. Most of the Hayden lies in this lower, less rugged country.

|

| FIG. 3.—Timber on north fork of Snake River, Hayden National Forest (F-189141) |

Although administered for future forest development, much of the forest is chiefly valuable at present as watershed protection. It also produces considerable forage. Nearly 7,000 cattle from Snake River and about 100,000 sheep from the desert found grazing grounds here in 1924, on small natural openings in the timber (known locally as parks), open stands, potential timberland denuded by fire before the days of forest administration—unfortunately there is much of this—and large parks and meadows above timber line. Unutilized, this forage, like the timber, would become not only a loss but also a fire menace, especially after it is killed by early autumn frosts. A certain portion of it must be reserved for the support of the wild game which have always made these regions their home—at least during the summer months. The wild game eat comparatively little, however, and leave most of the forage untouched.

GRAZING

By far the greater part of the forage on the Hayden, like that on other national forests, is available for the grazing of livestock. Through this activity a very important local economic need is satisfied. The producing capacity of the western stock industry is increased to the extent to which the forest ranges supplement the hay raised on the ranches for feeding. The use of the national forest grazing grounds during the summer months not only increases producing capacity, but it also enables the rancher to "turn out" and carry his livestock with less personal supervision during the season when his attention is required for the cultivating and harvesting of crops. He may pool his interests with neighboring ranchmen and hire a range rider for the season, or he may alternate with other owners in riding, each owner in turn looking after the combined herd. Topographic barriers tend to discourage drifting. and where they are absent it is often possible to close up small gaps with drift fences.

|

| FIG. 4.—Sheep in good forage on the lower part of Smith Creek, Hayden National Forest (F-179029) |

The successful handling of stock on this and similar remnants of the old open range is a highly specialized line of endeavor and involves uniform ultilization of the forage and the prevention of losses from straying, poison, and storms. The Forest Service is charged with the responsibility of administering the range as a public property, and in order to do this effectively it must carry on research which will enable it to guarantee the permanence of the range and prevent damage to forest reproduction.

The Wyoming National Forests pasture 125,000 head of cattle and horses and 575,000 head of sheep annually during the summer months, supplementing the feed supply of about 1,200 stock growers, most of whom are also local residents and property owners. A preferential system of allotting the range is followed by the Forest Service, whereby the temporary, speculating, or nonresident (Class C) owner must give way to the stockmen who are also local landowners, and whereby the large owner, even though local (Class B) must reduce within certain guaranteed limits for the small owner (Class A) in case the range becomes crowded. Use of the range prior to the establishment of any forest is also the basis for a preference on that range. On the Hayden, however, it was necessary to transfer some of the prior use preferences to near-by forests in Colorado to relieve the range from overcrowding. A regular or preference permit is binding on the Government for 10 years and amounts in reality to a contract. A fee for each head of stock is charged for all animals grazed, except a limited number kept by settlers, prospectors, and travelers for noncommercial purposes.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

circ-82/sec2.htm Last Updated: 29-Feb-2012 |