|

National Forests of Wyoming Miscellaneous Circular No. 82 |

|

NATIONAL FORESTS OF WYOMING

WESTERN WYOMING

Northwest of the Hayden National Forest, across the Red Desert, the Continental Divide again becomes mountainous. In this form it nearly parallels, with its many spurs, the western boundary of the State to the southeast corner of Yellowstone National Park, where it again takes a more westerly course. The entire mountainous region here is covered by national forests; the Wyoming and the Teton on the west side of the mountain range, extending to the south boundary of Yellowstone Park, and the Washakie and the Shoshone on the east side, the latter adjacent to the park along its eastern border.

These national forests have so many characteristics in common that, in many cases, what may be said of one applies to all. It is a vast, rugged region where many of the boundary lines are little more than devices for distributing equably the responsibility of administration. Nevertheless, since these lines are in most cases drawn along bold topographic features which separate major watersheds, each unit has points of especial interest which justify individual description.

Every summer many travelers enter this region in search of "nature" unspoiled. And they are plentifully rewarded, for "nature" is the dominant characteristic of the whole vast expanse. Within the forest boundaries roads are infrequent, and settlements are small and scattered; but outside, in the surrounding valleys, they are numerous enough to offer ample hospitality to the traveler. The higher country is rough and utterly unsettled.

|

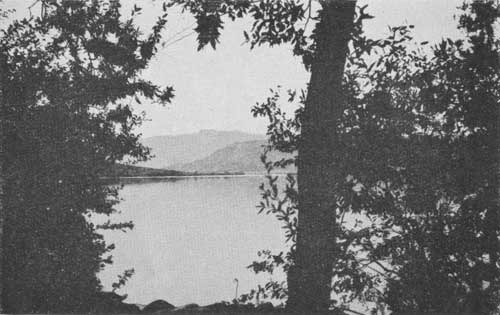

| FIG. 5.—One of the unnamed lakes above Brooks Lake, Washakie National Forest (F-179533) |

WASHAKIE NATIONAL FOREST

The southeastern portion of this great, broken upland is known as Washakie National Forest. It is named after Chief Washakie of the Shoshone Tribe of Indians, who spent his life among its mountains and on the adjacent plains and was ever a friend of the white man. On the map this forest has very much the shape of a reversed question mark in which the "dot" is separated from the hook by a corner of the Shoshone Indian Reservation.

Although this southern section, known as the Lander Division, was practically stripped of its old trees by fires many years ago, when the adjacent plains country was first being settled, it is still covered with forest growth sufficient for watershed protection.

The greater portion of the much larger northern division, drained by many tributaries of Wind River, is well timbered at the lower and middle elevations with lodgepole pine, the predominant timber type in the State, which gives place gradually, as a higher altitude is reached, to Engelmann spruce, alpine fir, and limber pine. Many of the creeks, however, which flow into Wind River from the south drain a rocky region in which the more scattered timber stands are of value chiefly as watershed protection. Such stands are incidentally valuable as shelter for wild life and as a scenic setting for various forms of outdoor activity. Automobile roads penetrate some of the steep-walled valleys of these streams for several miles, but most of the region can be reached only on horseback with well equipped pack outfits. Throughout this portion of the forest, recreation and livestock grazing are both important, but are subordinated, if it is necessary, to watershed protection.

Above the last timber-line outpost are broad mountain meadows and grass lands where bands of sheep graze around the foot of high, rugged mountain peaks that seem to touch the sky. Two of the highest of these, Gannett Peak and Fremont Peak, are on the boundary between the Washakie and the Wyoming National Forests, separating the headwaters of Wind River on the east from those of Green River on the west. In this formidable setting are several glaciers. The largest, in the head of Bull Lake Creek, possesses all the features characteristic of typical glaciers. The glaciers on Dinwoody Creek are nearly as large. Other smaller glaciers are located on Torrey Creek. This region is a veritable paradise for mountain climbers.

|

| FIG. 6.—On one of the Bull Lake camp grounds, Washakie National Forests (F-159220) |

The Wind River Valley, all but the head of which lies outside the forest boundary, separates the northern division into two portions, one of which, the northern portion, has a great deal of merchantable timber. Up through the ranch land in Wind River Valley runs the road from Lander, the terminus of the Chicago & North Western Railroad. Another road, coming from Riverton, joins it a few miles above Fort Washakie. Where the road crosses Wind River, at the mouth of Du Noir Creek, is the beginning of the Teton Game Refuge, in which no hunting is allowed. About 7 miles farther on, the road enters the Washakie National Forest and climbs more rapidly toward Twogwotee Pass in the Continental Divide, which marks the boundary between the Washakie and the Teton National Forests.

Descending into Jackson Hole on the west side of the divide, this highway leads to the southern entrance of Yellowstone National Park.

|

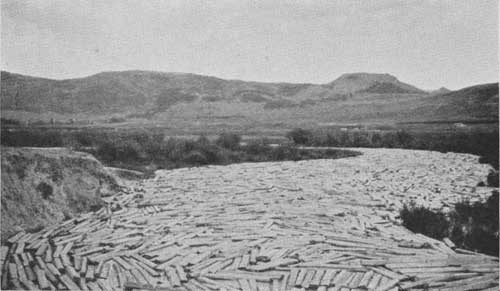

| FIG. 7.—Breaking a log jam on Sheridan Creek, Washakie National Forest (F-32409-A) |

LUMBERING

The notion that the Washakie is merely an impressive wilderness area is soon dispelled on a visit to the large tie operations in this part of the forest. On the upper slopes of the Wind River, 150 miles northwest of Lander, where the forest headquarters are located, is a camp of 200 to 300 woods workers, known as Du Noir. From the surrounding stands of timber are cut annually from 300,000 to 600,000 ties, which are driven down Wind River to Riverton. Here they are treated and afterwards distributed for use along the Chicago & North Western Railroad. This operation removes about 60 to 70 per cent of the volume of trees 10 inches and more in diameter on the area cut over, and cutting is carried on on such a scale as to assure a perpetual yield.

This sale is under the constant supervision of a forest service lumberman and three timber-sale rangers. The trees to be felled are selected and marked, the cutting is directed, utilization and brush disposal are supervised, and the final products are "scaled" and charged against the deposits made by the company, all by these forest officers. This work is not merely lumbering; it is also forestry, as the resource is perpetuated through the husbanding of the crop. The timber is sold on the stump and is handled by labor provided by the purchaser.

An interesting detail in this connection is the commissary of the camp at Du Noir. It is necessary to freight in all supplies, except hay and grain, more than a hundred miles, chiefly from Lander and Riverton. The average annual hauling program includes about 1 ton of food for each of the 200 or more men. The totals for some of the staples are as follows: Hay, 450 tons; oats, 225 tons; potatoes, 75 tons; flour, 50 tons; sugar, 25 tons; milk, 15 tons; canned fruits and vegetables, 30 tons.

Most of these provisions are purchased locally and are supplied by near-by communities. Their purchase is a powerful factor in stimulating business in the surrounding region. The industry which is made possible here and elsewhere by the utilization of resources in the national forests contributes consistently to community prosperity.

FOREST TYPES

Nearly 60 per cent of the timber in the national forests of Wyoming is lodgepole pine. In this forest type the individual tree is strikingly subordinated to the group or community; the characteristics of the type are those of the stand, not those of the tree. In fact, this pine rarely grows singly or in a stand composed chiefly of other species where it might have a chance to assert individual traits. So it is always the lodgepole stand. In Wyoming these stands are expansive and monotonously uniform—usually crowded. From these habits of the type come the form and habits of the tree, slender—rarely over 18 inches in diameter, "breast high," as measured by the forester—comparatively tall—often 90 feet to the tip—and always straight, with a short, light crown. If this tree were to be renamed to-day on the basis of use it would undoubtedly be known as the "crosstie pine," for its trim form makes it ideal for the hewing of railroad ties, as does also its uniform, crowded habit of growth.

|

| FIG. 8.—The 1924 tie drive in the Du Noir boom, Washakie National Forest (F-188298) |

The lodgepole pine belongs, botanically, to the hard-pine group. It has two short light-green needles in a bundle and small, "lop sided," very hard cones. The tenacity with which these cones cling to dead twigs in large numbers makes the tree very easy to identify.

Stands of the spruce-fir type, the most numerous and widely distributed of the subordinate types, contain trees of many ages and sizes and a considerable amount of underbrush. The appearance of such stands is equally characteristic but very different from that of the clean-bolled, even-aged lodgepole stands below them.

In sharp contrast to the lodgepole-pine type, the characteristics of the Engelmann spruce type are those of the individual imparted to the type. For this tree grows as an individual, permitting many other species to grow with it and under its shelter. Its tolerance of competition from outsiders results in great variety in the stand, usually to the complete sacrifice of the order and neatness that characterize stands of lodgepole pine. Alpine fir is a common satellite, incapable of reaching either the size or the age attained by Engelmann spruce.

Both Engelmann spruce and alpine fir may easily be distinguished from the multineedled pines of the State by their short, single needles. The sharp-pointed, stiff, four-sided needles of the Engelmann spruce, however, are very different from the blunt, pliable, flat needles of the alpine fir. There are other easy distinctions between the two—among them, the silvery, shiny bark of the alpine fir and its habit of carrying its cones upright in the very top of the tree. Very often in the fall or winter these cones are nothing but spikes, closely resembling Christmas candles, for, unlike all other conifers, the cones of the true fir trees shed their scales much as deciduous trees shed their leaves.

Engelmann spruce grows up as far as timber line, where, along the mountain tops, it takes the brunt of the endless struggle of forests to carry farther the limit of their conquests against wind and snow—defeated where a gap in the ridge gives the wind the advantage of a sweep, and undaunted where a few hardy individuals have seized a foothold in some partly sheltered nook. The many scars of conflict which these tree frontiersmen bear make them objects of curiosity and universal appeal to the traveler.

Both lodgepole pine and Engelmann spruce are interesting in their adherence to fairly well-defined zones of altitude, the former giving way to the latter between 8,000 and 9,000 feet above sea level.

In addition to the two main forest types there are two others, more restricted in their distribution: Douglas fir and limber pine. Douglas fir occurs in very limited areas in almost pure stands in the upper lodgepole and lower spruce zones, nearly always on moist north slopes. Limber pine is found in even more circumscribed areas. At lower elevations it grows usually on exposed, rocky sites, but toward the upper limits of tree growth it occupies better sites and forms stands of higher quality. In such localities limber pine often makes up a large proportion of the weird timberline forests.

TETON NATIONAL FOREST

HIGHEST USE POLICY

The Teton National Forest is the largest in Wyoming. On account of the wide variety of uses on its different parts, it is a fine example of the Forest Service policy of "highest use." It illustrates admirably the way in which the Forest Service plans the utilization of all resources—each in its own area. For example, there are areas where grazing is prohibited in order that plenty of range may be kept for the elk. There are other areas, each small in itself, where recreation reigns supreme and timber cutting, grazing, and other uses are subordinated to recreation. Still other portions are segregated as summer range for Jackson Hole livestock, and the southern part of the forest contains large stands of lodgepole ine, which offer favorable logging chances. Each of these uses is limited to a more or less definite area. In addition, the whole forest is of very great value as affording watershed protection and furnishing water to the ranches in the Snake River Valley of Idaho.

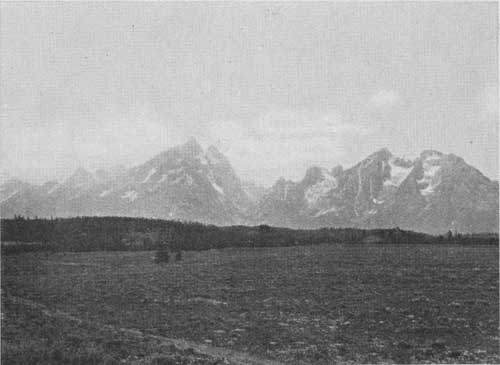

The Teton National Forest encircles Jackson Hole like a lopsided doughnut. It occupies the mountain ranges on both sides of Jackson Hole and extends northward across the valley of the South Fork of the Snake River and around Jackson Lake. Its southern limit is the boundary of the Hoback River drainage. In general the mountains in this circuit are not very high or rough, but they are heavily timbered—chiefly with lodgepole pine. The notable exception is the Teton Peaks, a relatively short range of high, scenic mountains lying on the west side of Jackson Hole. The division between the Teton and Targhee National Forests follows the Continental Divide, of which this range is the backbone. The streams on the eastern slope of Teton Peaks have eaten back on the divide between the mountains so far that at present these peaks are no longer on the main ridge, but lie entirely on the Teton Forest, considerably east of the boundary line. These bold mountains have perpetual snow on their peaks, and their tree growth, even on the lower slopes, is valued less as timber than as watershed protection.

|

| FIG. 9.—Looking into Jackson Hole from the summit of Teton Pass—Coming in from the east (Teton-Targhee line) (F-150318) |

North of Jackson Hole, along the Snake River and its tributaries, is a rolling, typical lodgepole pine country. Practically all the area north of the Buffalo River and Jackson Lake is within the State game preserve. There are also two other game preserves farther south on the Teton Forest. On these areas only a very limited amount of grazing is permitted. West of Jackson Lake and in the vicinity of the Teton Peaks are a number of smaller lakes having an outstanding value for recreation. They are very accessible and exceedingly beautiful, and will be treated by the Forest Service as a recreation area.

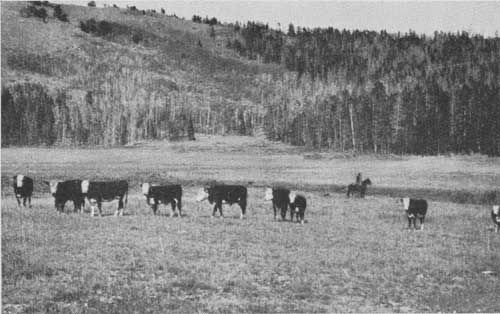

South of the Buffalo River the grazing value increases. Jackson Hole is an old-time cattle country and depends largely on the national forests for summer range. About 20,000 head of sheep also graze in the extreme south end of the forest.

Surveys recently completed on the Hoback River show that a large number of ties can be cut from the timber there. The logical means of utilization is to drive these ties down the Snake River to a shipping point in Idaho.

In general the Hoback River country is not particularly mountainous; the lower part of the stream canyons up, but toward the summit it spreads out into a grassy, open country covered with sagebrush, in which there are a number of scattered ranches. At the head of the Hoback River there is a scarcely perceptible divide between it and the headwaters of the Green River tributary. Far ther north the divide becomes higher and much more mountainous, and the main ridges dividing the various streams that run into Jackson Hole are likewise higher, the Gros Ventre Range in particular; but they are not cut up into spectacular peaks like the Tetons. Jackson Hole itself is probably an old lake bed, in which the Snake River has now entrenched itself to the depth of a hundred feet or so. Because of the coarse, gravelly soil and the high elevation, crops are pretty well limited to hay and cattle. Much of Jackson Hole, especially the northern part, is uncultivated and consists of stony or gravelly flats covered with grass, and, in places, sagebrush.

The small portion of the Targhee National Forest lying in Wyoming is enough like the Teton not to require separate description.

|

| FIG. 10.—The Tetons from the upper part of Jackson Hole—at the extreme right, Mount Moran cut in two—Teton National Forest (F-150319) |

WYOMING NATIONAL FOREST

The Wyoming National Forest includes two areas which for many years were administered as separate forests—the Wyoming and the Bridger. This combination, all of which is now called the Wyoming National Forest, lies like a broken horseshoe around the headwaters of the Green River. The eastern side of the horseshoe extends only up to the top of the Wind River Range, of which the Washakie National Forest occupies the eastern slope. Both the east slope and the west slope of the Salt River Range lie within the boundaries of the west side of the forest. The west slope of this range reaches down to Star Valley and drains into a tributary of the Snake River.

The two mountain ranges making up the two sides of this forest are rather different in appearance. The eastern side of the forest is much like the rugged country in the Washakie, the large ice fields and glaciers so conspicuous on the Washakie extending over onto the Wyoming. The main mountain crest is cut up into little peaks, and slopes off fairly rapidly to the valley of the Green River, a high, open, flat valley covered with sagebrush and scattered ranches, most of which are devoted to hay raising.

|

| FIG. 11.—Cut-over tie-sale area on Cottonwood Creek, Wyoming National Forest (F-192731) |

Near or just within the boundaries of this east side of the forest are a number of lakes which have a good deal of recreational value. The Green River Lakes are famous for their beauty; the others are perhaps less striking but rather more accessible. New Fork Lake, in particular, is much frequented, not only by local people, but by organizations such as the Boy Scouts from as far away as Rock Springs, Kemmerer, and Green River City.

The canyons are rather short and steep in these mountains and the timber units are not particularly valuable, although there is a good deal of lodgepole pine scattered through this forest.

|

| FIG. 12.—New Fork Lake, Wyoming National Forest (F-195128) |

The mountain range which forms the west side of the forest is much broader than that on the east. Greys River, rising well toward the south, drains almost its entire length. Several lesser streams drain from the headwaters of this river southward to the south boundary. This divide is not nearly so high and precipitous as is the main Continental Divide, across Green River Valley, and the tributary streams coming down to the Green River on this side are all bordered by extensive stands of lodgepole pine. The logging situation is good, and a large lumber company is now making a circuit along the eastern slope of this portion of the forest. The Green River working circle, which includes the Wyoming Forest as well as the parts of the Ashley and Wasatch on streams tributary to the Green River, is managed under sustained yield—the ultimate goal of forest management—and produces railroad ties for the Union Pacific Railroad. The broad, plateau-like top of the Salt River Range provides good forage for cattle and sheep. The steep slopes on the west side of the range extending into Star Valley contain bodies of timber which are more scattered than are those on its east side, or in the Greys River region to the north.

|

| FIG. 13.—The boundary of the Wyoming National Forest on the Star Valley side skirts these hills (F-190030) |

There is considerable demand from Afton and the other towns in Star Valley along the Idaho-Wyoming line for timber from Wyoming National Forest. This is a rather fertile, though elevated valley, and is fairly well populated. Dairying has been devoloped there, and a number of successful creameries are in operation. This valley also gets part of its timber and large quantities of firewood from the Caribou National Forest, on the opposite side, in Idaho. Most of the lodgepole pine, however, comes from the Wyoming National Forest.

|

| FIG. 14.—Cattle grazing on a small meadow in Lower Pole Creek range, Wyoming National Forest (F-20479-A) |

SHOSHONE NATIONAL FOREST

The Shoshone was Buffalo Bill's country. Names of places and things all the way from the town of Cody, the forest headquarters, which is named after him, to Pahaska Tepee, his old hunting lodge, 50 miles up the North Fork of the Shoshone River, keep fresh the memory of this famous scout. Hosts of people drive up the park road from Cody, and many spend their summers among the more remote timber stands on the Shoshone National Forest.

The Shoshone National Forest slopes eastward from the Absaroka Range and Yellowstone National Park toward the Big Horn Basin. Five good roads radiating from Cody cross or extend up into the forest at fairly regular intervals, following the main stream courses. The forest is so vast, however—it covers an area of more than a million and a half acres—that these roads give automobile access to only a relatively small portion of the forest. The intervening stretches are broken and rugged, although of no great altitude.

Timber development on this forest has been slow on account of the character of the country and its comparative inaccessibility to markets. But the timber "also serves" by waiting. Within a few years timber products from the Shoshone will undoubtedly be filling their place in local, if not distant markets.

The Shoshone National Forest is also important because of the protection it gives to watersheds. Within its boundaries are the headwaters of the Shoshone River, the Greybull, and Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone River. As a background for the many interesting geological formations in this region the stands on this forest add much to the beauty of the landscape. But far more important is the deterring effect of their spreading roots on the eroding action of wind and flowing water assaulting the steep slopes and the retarding effect of their spreading branches on the melting of snow. At timber line the bizarre witch tree renders this protecting service, constituting what is known as a protection forest. At somewhat lower elevations timber-producing stands protect the mountain slopes. The plan according to which timber sales are cut out on the national forests in no way impairs the effectiveness of the forest cover for watershed protection.

|

| FIG. 15.—Greys River, near the end of the road, in the Wyoming National Forest (F-190095) |

Those using water from the forests want it to be clear and steady in its flow. Both these requirements the forests help to fulfill. By holding the soil in place on the mountain sides they keep the water clear, and by delaying the run-off of spring rains and melting snow they tend to equalize the volume of water available throughout the year. Were it not that the forests act thus as soil binders, erosion might go on unchecked; the water in the streams would be muddy; the reservoirs, pipe lines, and ditches would fill up with silt. Fertile soil would be washed away from the mountain sides, thus depriving them of their forest-producing possibilities, and the silt would cover the more fertile soil in the valleys and curtail or destroy their productivity.

At the confluence of the North and South Forks of the Shoshone River is the large Shoshone Reservoir. The water in this reservoir is backed up by the huge Shoshone Dam built by the United States Reclamation Service. It took five years to complete this engineering achievement. The dam impounds the flow of these two large streams for distribution among the fields of the lower valley, serving in all about 100,000 acres.

Through this and other projects, some as yet only proposed, the rivers of the Shoshone National Forest may eventually irrigate some 200,000 acres of what would otherwise be sagebrush land.

There is more than a million acres of such land in the plains adjacent to the Big Horn and Yellowstone Basins, having favorable soils and potential farm value if water can be made available for irrigation. The importance of preserving the forest cover where it exists and extending it to other nonproductive mountain areas is therefore obvious. The future prosperity and agricultural development of the region are limited only by the amount of water that can be supplied for irrigation by the streams, many of which rise within the Shoshone Forest.

|

| FIG. 16.—A summer home in the Shoshone National Forest, just off the Cody Road, not far from Home Lodge (F-37504-A) |

These streams also provide drinking water for several towns and many ranches, especially those in the western part of the Big Horn Basin. For this use the water must be pure. Therefore, in the management of this and all other national forests where domestic water supplies are involved, other uses of the forest are so adjusted as to insure the water against pollution. This often requires special regulation of grazing, camp sites, summer homes, resorts, and saw-mills.

Anglers delight in these forest streams, in which they find ample opportunity to pit their skill and patience against the wiles of the wary trout. Many of the less accessible streams and lakes offer a sure catch, but others, especially those along the auto roads, have been pretty well "fished out." The problem of keeping the streams stocked is becoming acute on almost every forest.

In an endeavor to keep them stocked, the streams depleted by the hordes of motor fishermen are planted with fry hatched in the State fish hatcheries and the Federal hatcheries at Yellowstone National Park and Bozeman, Mont. By means of cooperation between the Forest Service and many local groups of fishermen, 2,800 acres of fishing lakes and 300 miles of streams in the Shoshone are planted with such fry.

|

|

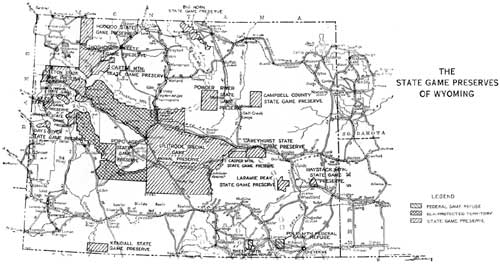

THE STATE GAME PRESERVES OF WYOMING. (click on image for a PDF version) |

GAME PROTECTION

The Forest Service is deeply concerned with the protection of game in this region. This involves not only the protection of the animals themselves but also setting aside for them suitable winter and summer range. Almost any area classified as forest land contains, in its high, inaccessible portions, plenty of summer range for big game. Because of the excessive snow in such places, however, during the winter, nearly all the game has to migrate to lower altitudes, where the precipitation is lighter and the stronger winds help to keep the ground bare. But most of the land at the lower level is also good for ranching and, accordingly, has been preempted for that purpose. This leaves, especially to the elk and deer, the rather desperate choice between death from the hunter's gun in the valley, or starvation in the snowdrifts of the mountains. Of four main game ranges on the Shoshone, only one, the South Fork, requires supplemental winter range. Game protection on the Shoshone varies from game protection on the average forest and deserves special mention only in so far as it is distinguished by this remarkable area of the all-important winter range.

Grazing is regulated in many places or excluded entirely in order to protect the game, especially on Elk Fork and Sweetwater, Horse, and Grizzly Creeks. Several refuges have been designated where no hunting is allowed, even with a license. These have recently been consolidated into two refuges, known as the Hoodoo and the Shoshone, comprising in all more than half a million acres. They are shown on the map on page 14.1 It will be noted that similar refuges are scattered throughout the other national forests also. As a result of these provisions and peculiarly favorable conditions on the Shoshone, an unusual number of different kinds of game live within its boundaries and the number is increasing. There are elk, moose, mountain sheep, antelope, mule deer, and black, brown, and silver-tip bear. Among the fur-bearing animals are beaver, fox, marten, mink, badger, ermine, and otter; among predatory animals, coyote, wolves, lynx or wild cats, and mountain lion. These predatory animals are very destructive to the more valuable game animals and are being reduced in number by systematic killing. It is estimated that during 1925, predatory animals killed over a hundred deer on the Shoshone National Forest, in addition to elk and mountain sheep. As deputy game wardens, forest rangers assist State officers in enforcing the State laws which are designed to preserve the remnants of wild life left from the days of the frontier hunter and the unfenced range.

1The exact boundaries of these refuges are changed frequently and may vary from those shown on the map.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

circ-82/sec3.htm Last Updated: 29-Feb-2012 |