|

A History of the Architecture of the USDA Forest Service

|

|

Chapter 1

Eras

"How many a man has dated a new era in his life from the reading of a book"—Henry David Thoreau's, Walden

1905-1917: From the Ground Up, or the Predesign Phase

When the Forest Service was established in 1905, employees carried out their duties in rented rooms in towns, in abandoned homesteads, and in tents in the field. Resources were so limited that these rangers even had to provide their own horses. The few Government-owned buildings that existed were small, poorly designed by the employees on the ground, and inadequate for conducting day-to-day business. [1] These administrative buildings were largely reflective of the rangers' personal preferences, as well as the materials, tools, and time available to them. Thus, these buildings, which had no apparent stylistic influences on appearance or construction, could be described as "pioneer." The special relationships between the barn, cabin, and corrals were similar to those of typical homestead layouts.

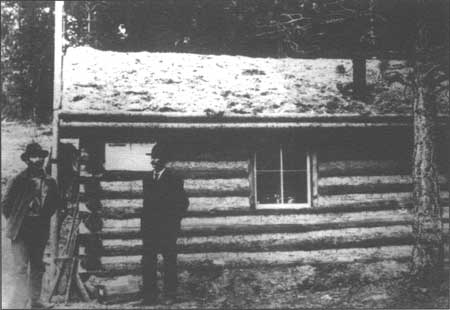

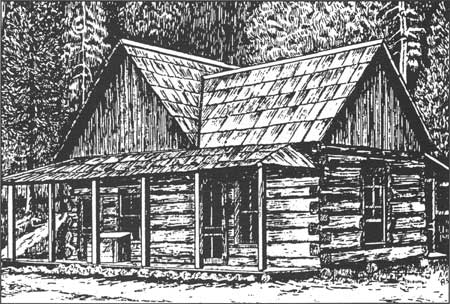

What is believed to be the oldest ranger station in the Forest Service, and certainly in Region 1, is located on the Bitterroot National Forest. Alta Ranger Station, as it is called, was built in 1899 for the Department of the Interior's General Land Office by pioneer forest rangers Nathanial Wilkerson and Henry C. Tuttle, who paid for the materials from personal funds that were never reimbursed. This sturdy 13- x 15-foot one-story log cabin (figure 1-1) served as a ranger station for 5 years. In 1904, it was sold to a private owner. [2]

|

| Figure 1-1. Alta Ranger Station, Bitterroot National Forest, Region 1, built in 1899 |

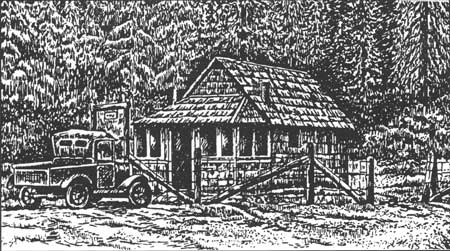

The earliest post-1905 Forest Service building that is still standing is the Wapiti Ranger Station on the Shoshone National Forest in Wyoming. This log-cabin ranger station was originally constructed in 1904 as two buildings: a three-room living quarters and a separate office. The buildings were joined by enclosing the space between them sometime before 1908 (figure 1-2).

|

| Figure 1-2. Wapiti Ranger Station, Shoshone National Forest (1908) |

During the early years, a forest ranger's living conditions were fairly primitive, and expenses and meals were usually paid out of the rangers' own pockets. In 1905, District Ranger Raymond Tyler, assigned to the Lake Tahoe Forest Reserve, submitted the following request:

Living accommodations in the Reserve have always been poor. The cold winter rain and snow of late spring and fall make it unhealthy to live in tents during the season. Our horses shiver in the icy winds and grow poor. If we bought hay we had little or no means of keeping it dry. When snow and bad weather come a ranger is compelled to live at some hotel and stable his horses, which is very expensive and more than I believe the Department expects. Therefore I ask that the Department allow some appropriation and ranger labor to build a house and barn.

Ranger Tyler's pleas for assistance were apparently heard. The following year, a house with three bedrooms, a kitchen, and a large sitting room was erected. The total cost of the house was estimated at $150. This building was perhaps the first Government-owned facility on what is now the Eldorado National Forest. [3]

Rangers such as Raymond Tyler relied heavily on Gifford Pinchot's The Use Book of 1905 for guidance which stated:

Eventually all the rangers who serve the year round will be furnished with comfortable headquarters. It is the intention of the Forest Service to erect the necessary buildings as rapidly as funds will permit. Usually they should be built with logs with shingle or shake roofs. Dwellings should be of sufficient size to afford comfortable living accommodations to the family of the officer. Rangers' cabins should be located where there is enough agriculture land for a small field and suitable pasture for a few head of horses and a cow or two, in order to decrease the often excessive expense for vegetables and food. He will be held responsible for the proper care of the buildings and the grounds surrounding them. It is impossible to insist on proper care of camps if the forest officers themselves do not keep their homes as models of neatness. [4]

Pinchot's instructions were straightforward enough, but a centrally located administration, poor communications, lack of personnel, and misinterpretation of new regulations often resulted in a lack of uniformity in field operations, including plans for improvements. Also, appropriations for improvements were more often based on arbitrary spending limitations established by Congress rather than on need.

Pinchot also established a ranger exam to eliminate undesirable ranger candidates. Applicants were expected, among other things, to be able to handle an axe and were tested on their knowledge of cabin construction. The Washington Division of Engineering was created in 1908, the same year that forest administration was decentralized into eight Districts, each with its own Engineering Division.

The design and feeling incorporated in the earliest administrative buildings placed importance on ideologies as well as function. Gifford Pinchot promoted the agency, its mission, and its policies, and Forest Service architecture played an important role in Pinchot's vision.

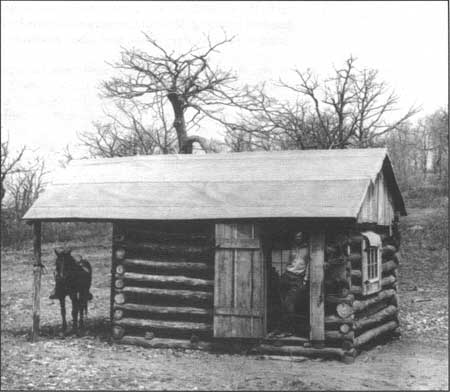

In Colorado, Ranger James Cayton selected the site in a secluded clearing near a spring for his yearlong station (figure 1-3). From his diary written 30 years later:

In September 1909 Forest Ranger Jolly Boone Robinson and I first started the improvements at this station. They consisted of a log barn and a three-room house. Ranger Robinson was given the task to cut and peel green blue spruce trees while I went out to work on my district.

When I returned, I took my bride of just a few days to the station site, where we lived in tents, cooking over a camp fire, then later on an old cook stove. We built the barn first and put the shingle roof on it, then moved into it as there was nearly two foot of snow on the ground and snowing most of the time. We chinked the barn, then dug a hole in the dirt floor, mixed the mud and daubed it on the inside. The barn made quite comfortable living quarters as compared to tents.

We laid up four rounds of logs for the house before we discontinued work for the winter. The next summer with the help of two others we completed laying up the logs for the house, installed partitions, put on the shingle roof and put in the doors and windows.

During that summer season of 1910 my wife and I put the chinking in the house and daubed it with mud. We also built the brick chimney, she being the hod carrier. That summer we moved into the Ranger Station, making it a year around headquarters from then until 1919 when I resigned and we went to California for her health. [5]

|

| Figure 1-3. Cayton Ranger Station, Region 2 (1910) |

Much of the rural architecture before 1900 was constructed with no formal architectural style. Utility, time, and the availability of materials were the principal forces behind their method of construction and appearance. Formal architectural expression and detailing were generally adapted variations of the local vernacular architecture. Depending largely on the availability of milled lumber, houses and offices were wood-frame or log construction.

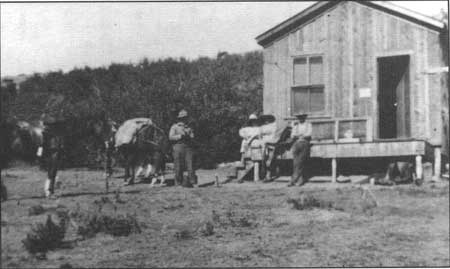

Temporary guard stations were often established at intervals of 1 day's ride on horseback from the established office in town (figure 1-4). These were used for fire patrols and overnight camping. Some were constructed exclusively for a timber sale. Important considerations for site placement included the availability of water, protection from the elements, accessibility to mail delivery, and existing or potential access to telephone lines.

|

| Figure 1-4. Log shack used as a temporary camp near Silers Bald, Wayah Ranger District, Nantahala National Forest, North Carolina (1916) |

After 1907, with creation of district offices (now regional headquarters), supervisors' headquarters, and ranger stations, more emphasis was placed on regional standardization of architecture. Originally, Forest Service architecture was epitomized by the simple log cabin, but that building type was superseded by rustic wood-frame structures of more conventional building techniques. The Forest Service intended to project an image of cleanliness, efficiency, and dedication to the public it served, and a crude log cabin did not fit that image. Exceptions were in the Pacific Northwest and northern Rockies, where log construction continued to be popular and was more economical.

Limited funding forced early forest rangers to prioritize improvement work. Eldorado National Forest Supervisor Kelley reported:

Improvements constructed now are more necessary for the efficient development of the forest and their [the rangers'] work in conjunction with fire plans, but in ranger district management I believe there is one thing a ranger should study out thoroughly and that is what improvements work should be done in the district. In making recommendations for permanent improvements, the prime issue is protection and the relation that the recommended improvement bears to it. We all know that our improvement appropriations are small and we must overlook a few little things and pay more attention to larger projects such as telephone lines, pastures, barns and houses, but I believe telephone lines are the most important. December 1912. [6]

In 1913, improvement appropriations for the California District totaled $60,000 for fiscal year 1914. The following year's allotments were increased by $5,000, but both construction and maintenance were covered by these funds.

Final authorization for new construction required approval from the Washington Office. Standard architectural plans were nonexistent prior to 1917; the development of floor plans, exterior appearance, and materials were left up to the individual ranger, with only a dollar limitation controlling the finished building. Most of the work was done by Forest Service employees using the knowledge, skills, and labor available at the local unit. [7]

On remote forests and sites located away from population centers, rangers designed and built the structures themselves. But there were examples where the buildings were constructed by private contractors due to lack of personnel on each forest and the lack of carpentry skills.

Looking at the remaining examples of these early buildings around the Nation shows certain trends. In the Rocky Mountain areas from Canada to Mexico, there is a predominance of log structures; on the West Coast (California, Oregon, and Washington), the buildings tend to be more wood-frame structures built from milled lumber. East of the Mississippi River, most of the national forest lands were purchased, and many of the Forest Service buildings were existing structures from the farms bought to make up the forests.

During this earliest era of the Forest Service, there were no known architects, private or public, involved in developing building plans or architectural style. Very few of the buildings from this earliest period have been preserved, and those that remain have been added to, remodeled, or changed their function. Most of the information about them comes from historic letters, reports, and oral traditions. Figures 1-5 through 1-9 demonstrate the style typical of this era.

Forest Service Buildings of the 1900's and 1910's

|

| Figure 1-5. Martin Creek Ranger Station, Santa Rosa Ranger District, Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest, Region 4 (Nevada) (1912) |

|

| Figure 1-6. Rangers on the Sierra National Forest construct the Jerseydale Ranger Station in the early 1900's. Dolly and Dick, the Reserve's work horses, assisted. |

|

| Figure 1-7. Supervisor's Office, Bridge Station, Sierra National Forest, Region 5 (1912) |

|

| Figure 1-8. Falls Ranger Station, Region 1 (1911) |

|

| Figure 1-9. Boathouse, Priest Lake Ranger Station, Region 1 (1911) |

Notes

1. Dana E. Supernowicz, Contextual History of Forest Service Administrative Buildings in the Pacific Southwest Region, p. 4.

2. USDA Forest Service, The National Forests of the Northern Region: Living Legacy, p. 230.

4. USDA Forest Service, The Use Book, p. 108.

5. Les Joslin, Uncle Sam's Cabins, pp. 64-67.

1917-1933: From Above

When the Nation entered World War I, many sawmills were closed because of labor and management conflicts, and the cost of lumber and materials increased. Improvements constructed during this period were generally modest in size and features. As of 1917, there was still no record of a Forest Service architect.

In the California Region, Regional Forester Coert DuBois issued an Improvement Circular on May 1, 1917. As DuBois explained:

The designs for buildings included in this Manual cover the field of buildings generally. From time to time, however, to meet special needs, small buildings, the plans and estimates for which are not included in this Manual, will be constructed. Maintenance of buildings already constructed now and then will require carpenter work of various kinds. The following chapter is written with a view of securing better construction and a higher grade of maintenance work by setting forth certain standards of construction and by giving ideas of how to do certain things which, to the inexperienced man, are more or less puzzling. Unless previous authority is secured, the specifications with respect to the dimension of materials for different purposes and the general type of construction shall apply to all common miscellaneous construction and repair work. [1]

The designs for the circular had been developed during the two previous years. They called for standard wood-framed construction in the larger structures with log construction employed for smaller buildings. The buildings were small and inexpensive to erect. The estimated cost for the 1D dwelling (figure 1-10) was $112 in labor plus materials, well within the $650 building spending limitation (see appendix B for plans and a list of materials). The buildings reflect the influence of the Craftsman architecture of the era and were obviously designed with an eye to more than strictly functional requirements. Designs such as dwelling 1D, with its classic, temple-inspired front porch, overhanging eaves, clapboard siding, and gable roof, would be right at home in any working-class neighborhood of the era.

|

| Figure 1-10. The classically inspired 1D dwelling, Region 5 (1917) |

While circumstances at times required the substitution of less finished material for the milled lumber, rusticity does not seem to have been the aim of the designers. If one compares the kind of buildings constructed by the National Park Service with the buildings built by the Forest Service in the 1910's and 1920's, it becomes apparent that the latter were not really all that rustic. In fact, given the mission of the Forest Service, it could be argued that rusticity would have been an inappropriate goal for the designers of the DuBois-era structures to pursue. [2]

In the Region 2 Office of Engineering, James Brownlee, a mechanical engineer, was overseeing the design and construction of administrative improvements based on the Forest Service policy that stated, "Each new improvement [shall be] carefully planned, and all details of construction [shall be] carefully included in each plan." [3] These plans exhibited increasing use of the bungalow style (figure 1-11). Another influence changing the style of the buildings was that a growing number of rangers after World War I were trained in the forestry schools on the East Coast. These men lacked the pioneer construction skills, and many stations were constructed by building contractors. [4]

|

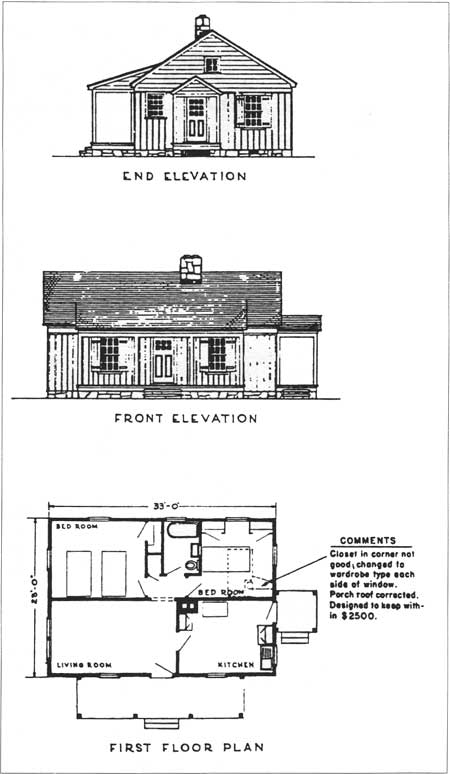

| Figure 1-11. Plans for ranger dwelling. Glade Ranger Station, Region 2 |

The 1928 Forest Service National Manual of Regulations and instructions was the first Service-wide publication to address design policy since the Use Book. It stated that dwellings would be built only when it was impractical to rent living or office space. Office space was to be provided apart from dwellings. The first office designs from the various Regions would appear 3 years later. Garages were for official vehicles only. [5]

A companion to the National Manual, the Construction and Maintenance (C&M) Handbook, was also issued. Included in the C&M Handbook were plans for various types of buildings. These were not mandatory, but were used in many Regions of the Forest Service.

A significant innovation in Region 1 fire control planning was the development of the Ninemile Remount Depot on the Lolo National Forest. The Forest Service had always relied on horses and mules for getting supplies into the backcountry to fight fires, and in the early years the common practice was to hire commercial pack stock when the need arose. The rise in the number of automobiles and trucks in the 1920's, however, had caused a commensurate decline in the number of horses. In 1929, Clyde Fickes recommended that the Forest Service acquire its own reserve of pack stock and saddle horses at some central location, where they could be trucked to any point in the Region at short notice. Fickes had in mind the old remount depots of the U.S. Cavalry, where saddle horses were trained for issue to replace lost mounts. Although Fire Chief Howard Flint and others in the Regional Office opposed this idea, Regional Forester Evan Kelley gave it his approval.

Kelley put Fickes in charge of the remount operation, but he gave it close supervision, too. William Fox, the first professional architect, designed most of the buildings. Many of the facilities and equipment were completely innovative, such as the horse trucks designed specifically for transporting a standard pack string of nine mules and a saddle horse. "Kelley . . . really wanted it to function as planned." writes Fickes. "No one else in the RO wanted to have much to do with it because they were afraid they would get their fingers burned. After we made it prove its worth, then everybody wanted to get into the act." The Ninemile Remount Depot was a complete success; its value increased as the level of activity rose. [6]

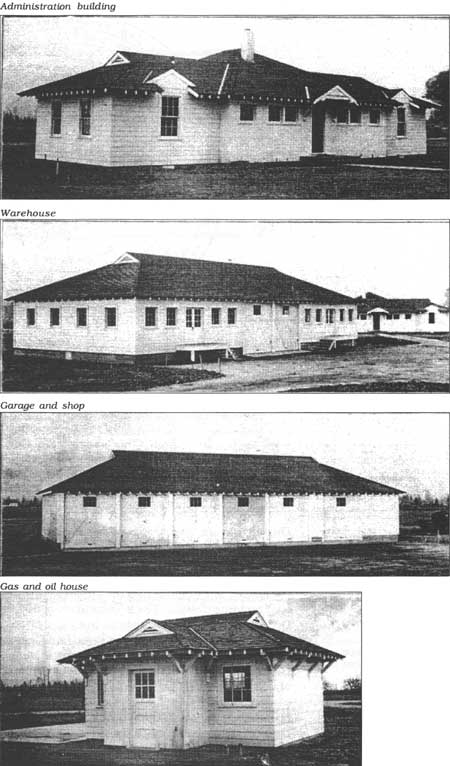

William Fox designed the buildings for Ninemile in the Cape Cod style of architecture. The site plan was devised to look like a Kentucky horse farm, with clean white buildings, corrals, and tree and grass landscaping (figures 1-12 and 1-13). The reasons for selecting this type of architectural style are unclear; however, it appears to have been the personal choice of Fickes and Kelley. [7]

|

| Figure 1-12. Residence, Ninemile Ranger Station, Lolo National Forest (1931) |

|

| Figure 1-13. Office, Ninemile Ranger Station, Lolo National Forest (1931) |

By 1930, Forest Service appropriations shifted to emphasize fire protection structures rather than administrative improvements. In a letter to the forest supervisors. Region 5 Regional Forester S.B. Show stated that, unlike past practices, the Washington Office was now emphatic about not transferring funds from one function to another. As Show pointed out, "The money allotted for protection improvements must be spent on such and no transfers should be made between administrative or protection improvement construction and maintenance projects without approval." [8]

By the 1930's, rangers were required to own their own vehicles rather than horses. Motor vehicles helped stimulate a road construction boom in the 1920's that resulted in increased recreational use and timber and mineral extraction. Rangers used automobiles and trucks to expedite their field work, and their families enjoyed easier access to the supplies and social contact available within nearby communities. This initiated an administrative policy shift that resulted in the consolidation of districts and the replacement of full-time rural ranger stations with seasonal or temporary stations served in the summer by rangers who lived in towns the rest of the year.

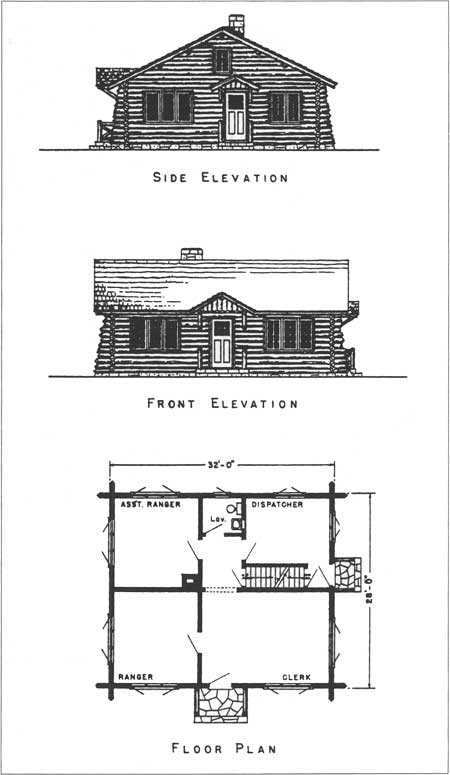

The introduction of designed office space in 1931 and the construction of various other buildings at administrative sites increased the need for site planning. Guard stations may have had only a single one-room cabin, but typically consisted of a two- or three-room dwelling and a small barn. Another innovation at this time was the combination office building that included office, storage, and living quarters when built at remote locations. The architectural appearance of these differed throughout the country depending on the local styles and materials available. Figures 1-14 through 1-17 show some of the styles of this time period.

Forest Service Buildings of the 1920's and 1930's

|

| Figure 1-14. Ranger residence, Cabin Lake Ranger Station, Deschutes National Forest, Region 6 (1923) |

|

| Figure 1-15. Pelki Ranger Station, Region 1 (1925) |

|

| Figure 1-16. Twin Lakes Ranger Station, Region 1 (1924) |

|

| Figure 1-17. Boise Assay Office remodeled as the Supervisor's Office, Boise National Forest, Region 4 (1933) |

In 1932, the Washington Office requested that the Regions develop a careful policy and program before beginning any major Government-owned improvement project, and suggested that the following factors determine the need for such projects:

1. Location.

2. Certainty as to permanence.

3. Adequacy of present plant.

4. Annual rental and other costs of present plant.

5. Chance to rent satisfactory facilities, including chance to get satisfactory facility constructed for rental to the Service.

6. Full and complete cost for site and construction of a permanently satisfactory plant.

7. The $2,500 building limitation required construction of buildings of proper design.

8. Annual maintenance and upkeep cost of such a Government-owned plant.

Public opposition to Forest Service personnel and policy continued during this period. Buildings therefore continued to blend with the local culture, much as they had in the earlier period. The separation of office and residence had practical applications, but may also be reflective of the Forest Service's goal of integrating the rangers into the fabric of the community by physically separating them after hours from their official duties.

Notes

3. Jim Schneck and Ralph Hartley, Administering the National Forests of Colorado, p. 47.

5. Schneck and Hartley, Evaluation of R-1 Forest Service Owned Buildings for Eligibility to National Register of Historic Places, p. 48.

6. Historical Research Associates, p. 58.

1933-1938: Groben Dictates

T.W. Norcross was Chief Engineer of the Forest Service from 1920 until 1947. Sometime around 1933, he hired the first and only Washington Office architect, W. Ellis Groben. Groben was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He was doing residential design when he came to the Forest Service, and he had served briefly as chief architect for the city of Philadelphia. He put his skills as both residential designer and public administrator to work guiding the Forest Service as it continued to create its own style of architecture.

Groben felt that current Forest Service design did not "possess Forest Service identity or adequately express its purposes," so his time with the Forest Service was spent producing concepts for Forest Service buildings. A book of "Acceptable Plans, Forest Service Administrative Buildings" was issued in 1938. Norcross, in his cover letter, stated:

The purpose of this collection of building plans, developed in the respective Regions for various types of buildings, is to make the best ones available for the Forest Service generally. This does not signify that the present collection contains all that are meritorious and acceptable.

However, by reference to this volume, a plan may be found that will suit the purpose, either in whole or in part, thereby frequently obviating the necessity of preparing an entirely new scheme. [1]

In the foreword to this publication, Groben says:

Forest Service areas are not exclusively parks nor recreational in character but, in addition to offering these facilities, they serve highly utilitarian purposes generally, as a result of which it becomes necessary to provide buildings to adequately accommodate and house the personnel and equipment required to properly conduct the varied phases of Forest Service work.

No matter how well buildings may be designed, with but a few exceptions, they seldom enhance the beauty of their natural settings. They are, however, required and necessary to satisfy definite uses which arise to meet human needs, in spite of their encroachment upon Nature's pristine beauty.

For the benefit and assistance of all those concerned, it has been deemed highly desirable to present the best thought in these matters in a convenient manner by assembling this collection of plates to be known as Acceptable Plans, Forest Service Administrative Buildings. [2]

Concerning style, Groben says:

The designs now in vogue are based upon variations of imported styles, foreign in character to a particular Region and not unlike other city or suburban buildings. Accordingly, they fail to possess Forest Service identify or to adequately express its purposes. Consequently, they are subject to adverse criticism, much of which is well founded.

To accomplish the desired results. Regions not fortunate enough to have any traditional architecture must resort to the development of original designs based upon typical regional prototypes, refraining from the use of established styles now recognized as unrepresentative of the ideals and purposes of the Forest Service.

Therefore, the first step in this procedure is to zone the Region for architectural styles, based upon climatic characteristics, vegetation, and forest cover. This has been done very logically by one Region in the following manner:

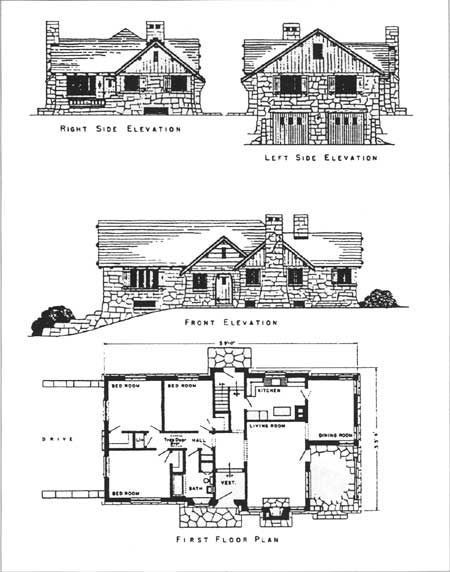

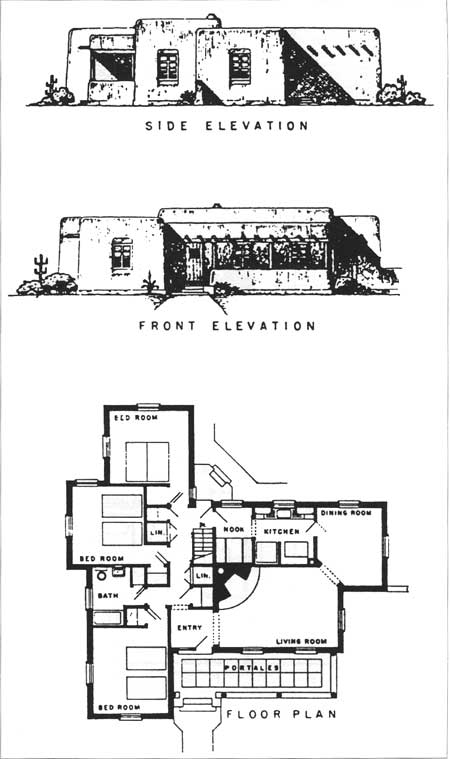

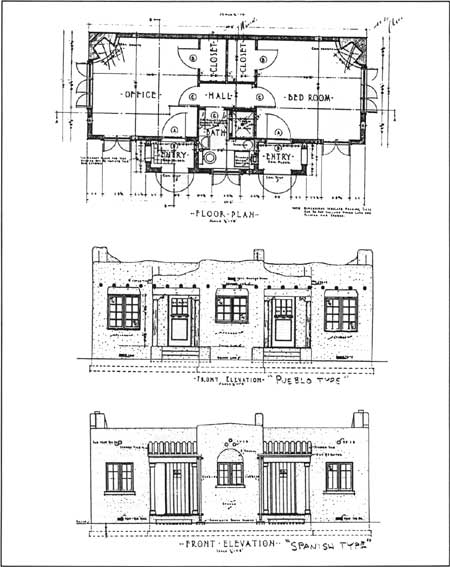

Type of Country Style of Architecture Desert or semidesert Adobe or Pueblo Grassland Ranch-house type Woodland (pine, fir, or spruce) Timber types Alpine Alpine type (stone or stone and rough timbers) These general classifications represent a reasonable subdivision of the Region into localities typified by different natural characteristics and the respective type of design appropriate to each. [3]

The drawings on pages 28 through 32 show examples of Groben's architectural styles.

The preface to "Acceptable Plans" starts with:

In assembling this collection of plans and elevations, known as Acceptable Plans, Forest Service Administrative Buildings, the Division of Engineering has undertaken to select those which embody the recognized principles of scientific, economic planning, which satisfy present day needs as a guide for similar future structures.

In no sense are they to be construed as 'Standard Plans' for the simple reason that, as more fully explained in the subsequent text, no plans can be singled out and designated as a universal standard. The moment a so-called 'Standard Plan' has been prepared to satisfy existing requirements, it immediately becomes subject to further improvement to suit conditions which do not remain fixed or standard but which are continually changing. [4]

Following in the preface, Groben gives a short course on Architecture.

Site Investigation. Once the need for a building in a particular locality has been determined, the next step is the selection of a desirable site, a matter which cannot be successfully accomplished without a thorough knowledge of all the physical conditions concerning it.

To simplify this undertaking, a standard form entitled 'Questionnaire Covering Conditions at Proposed Sites of Forest Service Building Developments' has been prepared to provide a convenient and uniform system of tabulating all the vital statistics necessary for a practical decision. [5]

Comprehensive Planning. While the subject of planning is entirely too extensive to attempt a complete discussion of it here, nevertheless, there are certain recognized fundamentals which should be seriously considered.

He goes on to list nine issues to be covered and then moves on to the type of building plan to be considered:

The success of planning individual buildings depends to a large extent, upon knowledge and experience in determining the type of plan which best fulfills its specific requirements.

For this purpose, one must be familiar with such plan types as the square or 'box' plan, the rectangular plan, the 'T', 'L', 'H', 'U', and other shaped plans, as well as their respective advantages or disadvantages. [6]

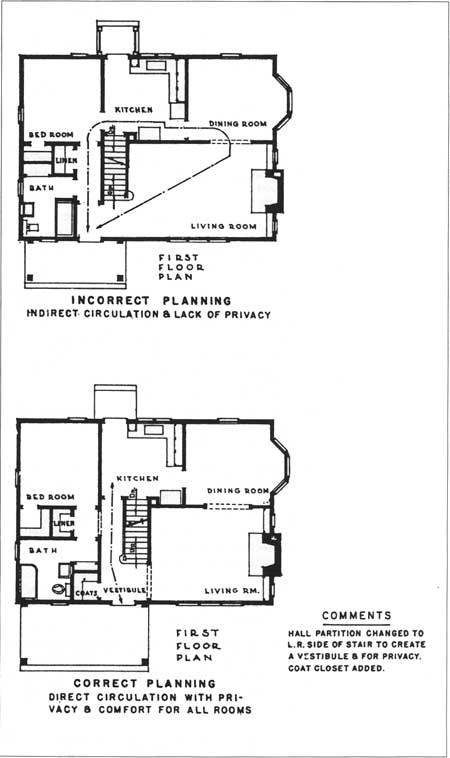

He says the book was assembled for the purpose ". . . of making immediately available a group of typical plans, based on those principles of correct planning in which such fundamentals as ample daylight, cross-ventilation, direct circulation, etc., are paramount and in which the following faults of bad planning do not occur." [7]

He then lists 11 faults common to his observations of past planning. These include dark interior spaces, dangerous stairways, failure to provide a vestibule where weather extremes occur, rooms used as passageways (figure 1-18), rooms having insufficient usable wall space, bedrooms where a bed must be located in a corner next to a wall and moved to make it, linen closets in bathrooms, insufficient closet space, and excessive central hallways, which are uneconomical.

|

| Figure 1-18. Groben provided guidance to helpo architects avoid using rooms as passageways |

From there he moves on to preliminary data, listing facts the designer should obtain prior to starting planning and designing relating to the standard plans in the book.

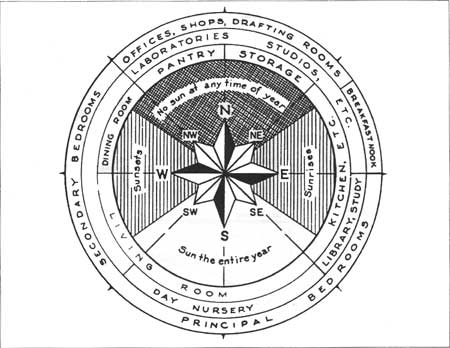

Next he deals with the orientation of the building and rooms in their relation to sun, prevailing winds, type of room involved, climate of the site, and so forth. He specifically talks about location of the kitchen in cold climates; it should be on the north exposure due to its cook stove. This would be the warmest room and in that position would afford the other rooms with protection against cold north winds. He provides a diagram that covers all of the above [8] (figure 1-19).

|

| Figure 1-19. Groben's diagram on building orientation |

Groben then covers the topics of topography, elevation design, service facilities, minor structures, and delineation (drafting of the plans for construction). He states:

Groups of buildings should possess similarity of character and appearance, based upon correct principles of design, whether or not they conform to any particular style. The Sandpoint Ranger Station, Idaho, Region 1 [figure 1-20], is an excellent example of uniformity of style. [9]

|

| Figure 1-20. Sandpoint Ranger Station in Region 1 was praised by Groben for its uniformity of style |

The conclusion of the preface states:

The planning of buildings and their construction, etc., are matters involving not only a thorough technical knowledge but also a broad understanding of social and economic conditions. . . . It is hoped that this collection of plates will be found useful in planning Forest Service structures and that the various Regions may be assisted constructively by having been assembled and presented in this manner. [10]

The preface is 23 pages long and includes several drawings, plans, and charts. The rest of the book covers various types of buildings, with floor plans, styles of elevations, and sketches. Groben felt this 'bible' would provide better architecture for the whole agency.

During this era, design was first to be more influenced by Forest Service philosophy than by national or local stylistic trends. In these designs can be read the architects' struggle to reconcile regional and national Forest Service design policies, current architectural trends, and local building traditions. The Regions had the opportunity to use, modify, and create their own building designs. These sometimes conflicted, as in the anomalous Art Deco or Classic Revival designs, but more often resulted in the more successful blending of philosophy, style, and local tradition promoted by the designs illustrated in "Acceptable Plans, Forest Service Administrative Buildings." Mostly devoid of superfluous ornamentation, it was the richness of texture, sense of craftsmanship, and juxtaposition of shapes and materials that made these buildings aesthetically pleasing. These structures reflect both national and local architectural trends and building philosophies of the Forest Service that include utility, respect for nature, and harmony with the environment.

|

| Figure 1-21. Estes Park Ranger Station, Region 2. |

|

| Figure 1-22. Residence, Huerfano Ranger Station, San Isabel National Forest, Region 2 |

|

| Figure 1-23. Four-room house, Sublimity Forest Community, Region 7 |

|

| Figure 1-24. Building elevation, dwelling no. 1, Pagosa Springs Ranger Station. |

|

| Figure 1-25. Log Ranger Station Office, Region 9 |

Notes

1. USDA Forest Service, Acceptable Plans, Forest Service Administrative Buildings, Cover letter accompanying distribution.

2. USDA Forest Service, Acceptable Plans, Forest Service Administrative Buildings, Foreword.

1934-1946: Civilian Conservation Corps to the End of World War II

Before the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933, the Forest Service operated with limited Government support and financial resources to oversee its vast and untamed domain, then found itself on the verge of unprecedented expansion. The newly elected President put men to work doing environmental conservation on public lands; the Forest Service, which managed a major portion of these lands, presented a perfect vehicle for implementing the goals of the New Deal. Some 250,000 men were put on the Federal payroll, working for the common good.

Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace graphically and succinctly described the state of the Nation's natural resources:

Thoughtlessly we have destroyed or wounded a considerable part of our common wealth in this country. We have ripped open and to some extent devitalized more than half of all the land in the United States. We have slashed down forests and loosed floods upon ourselves. We have torn up grasslands and left the earth to blow away. We have built great reservoirs and power plants and let them be crippled with silt and debris, long before they have been paid for. [1]

What began as an ambitious project soon mushroomed into one of unprecedented scale, as the number of men enrolled in the CCC doubled its size within its first 2 years. More than 3 million men had signed on by 1942; almost half of the total output was administered by the Forest Service, much of it going into construction.

Because the national forests were not parks, they were intended to serve highly utilitarian purposes and not be exclusively recreational. It was necessary to provide buildings adequate to accommodate and house the personnel and equipment required to conduct properly the varied phases of Forest Service work. In accordance with the decentralized organization of the Forest Service, each component became responsible for specific elements of planning and implementation. Ellis Groben had just started in the Washington Office when building designs were needed quickly for the CCC projects (see the previous section in this chapter for more information on Groben's design concepts).

In the Region 1 office, Clyde Fickes was placed in charge of recruiting a staff of architects, landscape architects, and mechanical draftsmen to supervise the improvement program. William Fox, a Butte native and recent graduate of the University of Washington's School of Architecture, was hired as the first architect. During his interview with Fickes for the position, Fickes told Fox he wanted an architectural staff to design all the buildings required by the Forest Service. Fox was skeptical, thinking the job would entail more structural engineering than architecture. Fox eventually headed a staff of six or seven architectural draftsmen.

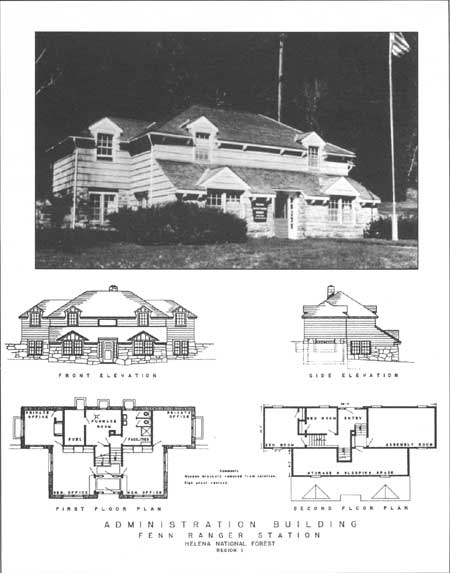

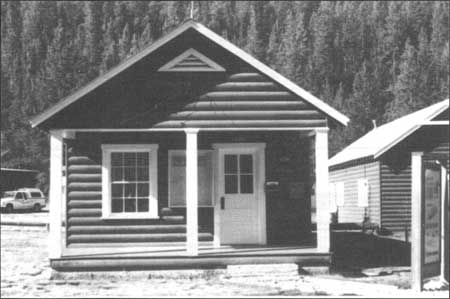

Fox designed the buildings for the Fenn Ranger Station with the "Georgian" appearance (figure 1-26). This complex is located in rural Idaho and administered by the Nezperce National Forest. All of the buildings are wood frame and exhibit combinations of structural and decorative details that give them a "Georgian" look. These include the use of hip roofs and dormers and the decorative door surrounds at the front entries. A rustic appearance is achieved through the use of natural stone facing on the bottom one-third of the buildings and/or the use of wide board siding.

|

| Figure 1-26. Fenn Ranger Station, Nezperce National Forest, Region 1 |

Region 2 hired its first professional architect, S.A. Axtens, in 1936. Although he stayed only 1 year, he was involved in the design of several stations, including the Delores Ranger Station on the San Juan National Forest (figure 1-27). He attempted to follow Groben's statement: "Practical and workable plans lend themselves readily to good elevation design."

|

| Figure 1-27. Delores Ranger Station, San Juan National Forest, Region 2 (1933-1938) |

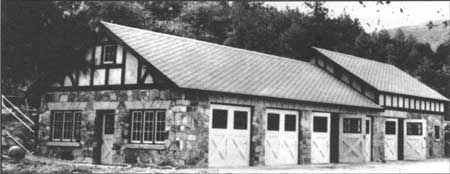

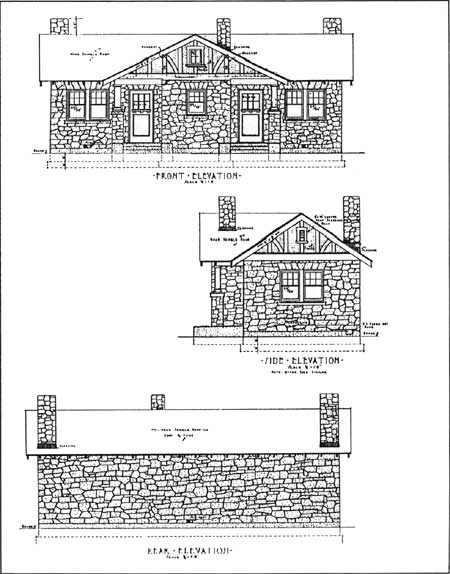

After Axtens left, W. Earle Jackson supervised a staff of 11 architects who produced detailed plans for nearly every building constructed in the Region during this era. Designs included a variety of dwellings, office buildings, garages, and barns, as well as various associated buildings. Supervisor dwellings were constructed near the headquarters in at least 12 of the 14 forests. The Region 2 style was more rustic than any other; it included uncoursed local stone or brick, walls of peeled or shaved logs or wide clapboard siding, and moderately pitched roofs with wood shingles or shakes (figure 1-28). Pueblo-style buildings were built only in the southern half of Colorado where that style was commonly seen.

|

| Figure 1-28. Land's End Shelterhouse, Grand Mesa National Forest, Region 2 (1937) |

Region 2 had ambitious long-range plans for construction of administrative facilities, and this was the first time it had the means to pursue them. [2] Fifty-six CCC camps were in operation in the Region by August 1933.

The designers responded to climatic conditions, especially the deep snows found at higher elevations, by raising the foundations of rustic-style buildings several feet above grade. Simple gable roof forms, strongly reinforced, were meant to cleanly shed heavy snow, which fell away from the building because of the deep overhangs. Many porches had large areas adjacent to and protective roofs over the entries. [3]

The use of wood as a construction material was perhaps the ultimate expression of Forest Service values, and designers took every opportunity to use it. Wood was cheap, readily available, and reflected the pioneer architectural traditions of Rocky Mountain architecture. Rustic style was especially appropriate for the mountains, where wood shakes, native stone, and logs were available.

The rustic tradition made use of modern technologies and covered them with materials that appeared handcrafted and traditional. Rustic design utilized stone veneer over unreinforced poured concrete foundations; milled log cabin siding imitated the appearance of real logs.

Region 2's rustic architecture was highly reflective of the Forest Service philosophies of harmony, utility, and the use of natural materials. Forest Service personnel took great pride in their buildings. Extensive construction records document the extraordinary care taken by rangers in making sure their buildings were as well built as possible. This rustic architecture used a strong horizontal emphasis, complimentary colors, extensive use of wood and stone, and lower overall massing to harmonize with the Rocky Mountain environment. It characterized vernacular building techniques and construction in its axe-cut log crowns and rafters, saddle notching, and unfinished stone while simultaneously utilizing the latest construction technology available. Interiors utilized wood or wood byproducts to every extent possible. [4]

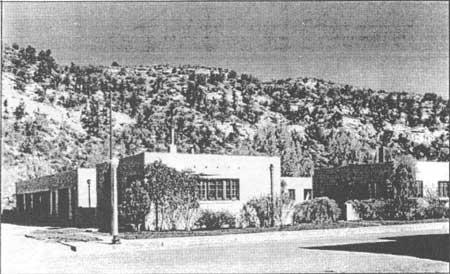

In Region 3, 15 CCC camps were opened. Numerous facilities were constructed on national forest land. Administrative facilities included staff and crew residences, offices, storage buildings and barns, garages, warehouses, and fire lookout towers. A distinctive architectural style identified these new facilities with the Forest Service.

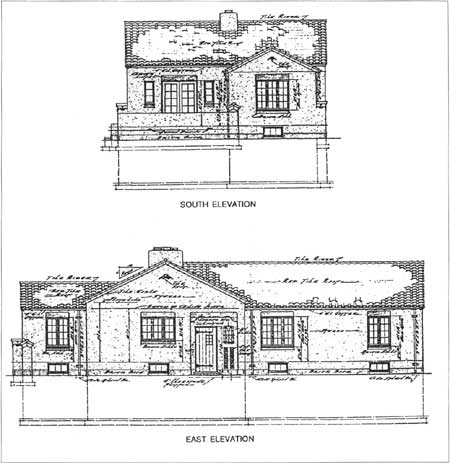

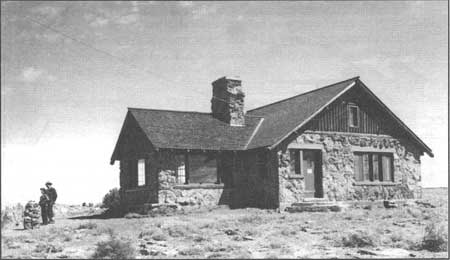

A bungalow type with low pitched gable roofs sheathed with asphalt shingles also became common (figure 1-29). Rafter ends were exposed under wide eaves. Exterior chimneys were prominent. This style was popular for Arizona national forests. A Spanish type with flat roofs with parapeted walls also emerged. Offices and dwellings had narrow, tile-covered shed roofs above entryways and porches. Only a few buildings were built with this style.

|

| Figure 1-29. Crown King Ranger Station Office. Prescott National Forest, Region 3 (1936) |

In New Mexico, buildings were designed using a pueblo style. Also having flat roofs with parapeted walls, the parapets were stepped in a line using a regular pattern. Standard plans used vigas projecting in front and rear. Wood lintels were installed over windows and entrees but not exposed. Construction materials were limited to adobe with stucco veneer.

Region 4 hired its first architect in 1928. George Nichols remained with the Region until 1956. His first significant project was the development and design of a Regional Headquarters, which was funded by Congress in 1931 as part of a Deficiency Bill (a precursor to the CCC program). This project is described in the section on Administrative Buildings.

One focus of construction by the CCC was recreation facilities; these included toilets, bathhouses, campground tables, stoves, and shelters.

Regional Forester S.B. Show authorized the hiring of a private firm of professional architects, Norman Blanchard and Edward J. Maher, to form the Region 5 architectural unit. These were the first professional architects in the Region, and they produced all the buildings constructed until 1938.

In the California Ranger dated June 16, 1933, Chief of Lands L.A. Barrett said that the new architects would bring a renaissance in Forest Service ranger station architecture:

The firm has been engaged for the purpose to create an 'All-American' style. Old World influences are barred and Uncle Sam's new ranger stations will represent only the best of the U.S.A. Not only will the lines of our ranger stations be revamped, but the color scheme will be improved. The green roof will be retained, but the French-battleship gray paint . . . will be changed to a brown stain to blend appropriately with the colors of the forest.

Blanchard and Maher described what their architectural style was to be: a "Mother Lode" style influenced by William Wurster's vernacular building designs, later known as "California Ranch House style."

In 1935, the $2,500 building limitation was in effect. However, no contributed labor was allowed except for the CCC crews, which were used primarily for rough labor such as constructing basements, rough framing, roofing, and building rock walls. Blanchard and Maher noted that:

In order to keep all buildings, large and small, within such a comparative unit cost, methods rather unusual at the time were necessary to effect such economy. [5]

The team developed similar designs for 13 separate categories of buildings: dwellings, lookouts, fire barracks, offices, garages, warehouses, and barns. The first year it was estimated that 450 structures were constructed at elevations from sea level to over 8,000 feet. To overcome the problems of climate variability, a standard structural design was used throughout all buildings, with specific design requirements for severe snow and extreme heat and cold. [6]

Where other areas of the United States were experimenting with prefabrication, Blanchard and Maher decided that this system had little to offer on the West Coast. Rather than prefabrication, they adopted a "ready cut" design. The ready-cut system of building was adapted to home and commercial building construction shortly after 1900. This was similar to the automobile industry's system for mass production. During the 1920's, the growing home market had created a demand for inexpensive housing, in particular for suburban tract housing. The depression of the 1930's only increased the demand for affordable housing and designs such as the ready-cut house.

The ready-cut system used pre-cut lumber rather than preassembled components. It allowed for field innovation and reduced the shipping volume. Builders in California preferred the system to prefab and felt it provided a better more aesthetic finished building.

Wood was the preferred material in California, and administrative buildings were finished with wood both inside and out. The architects explained:

The outside finish was clear, all heart redwood or western cedar. This was installed over building paper and shiplapped diagonal sheathing. On the inside, clear Douglas-fir or ponderosa pine was used to panel the interior. [7]

Region 5's mass ordering and ready-cut materials distribution benefited both the lumber industry and local communities. The majority of the buildings begun in 1933 were completed before winter with the help of the CCC crews. The Regional Engineer wrote:

Reports are all in and tabulated on the status of our ready-cut building and warehouse program as of November 15. By unanimous agreement of reviewing officers, first prize goes to the San Bernardino, with the Stanislaus, Lassen, Mono Modoc and Santa Barbara receiving honorable mention. [California Ranger, December 1933]

Between 1933 and 1936, some 1,200 buildings were constructed in California. In addition to supervisor's headquarters, ranger and guard stations, and experimental station facilities, fire lookouts were erected in large numbers—45 in one contract. [8]

Blanchard and Maher's work for the Forest Service reflects several of the major themes that ran through American architecture of the 1930's. Their use of the ready-cut construction system was one of many experiments with unconventional building techniques, which can be seen as an effort on the part of the architectural community to contribute to solving the Nation's pressing economic problems. Use of what they called the Mother Lode style of building was part of a larger effort on the part of American architects to develop architectural styles that were seen as being appropriate to regional historic and environmental conditions. Even in their use of the Colonial Revival mode, they were responding to the national vogue for that type of design, which in the mid-1930's was the most popular architectural image in the country for domestic design. [9]

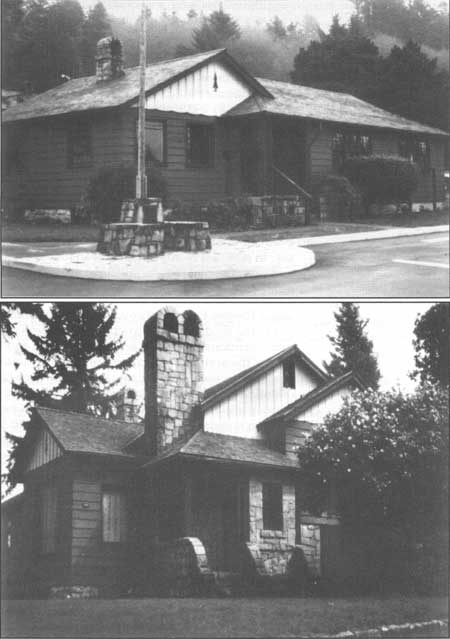

In Region 6, once the forests provided pertinent data regarding site orientation and topography, the Regional Office architect, Tim Turner, was able to design individual buildings that were appropriate, attractive, and practical. Design of elevations was to some extent limited by the use of a restricted number of materials native to the area for exterior construction. Climatic conditions, environment, and economy also imposed certain limitations. The sizes, shapes, and finished surfaces of the various forms of wood used in the exterior walls of frame buildings were the attributes that largely determined their design. Only mass, line, proportion, window and door design, and color remained unrestricted.

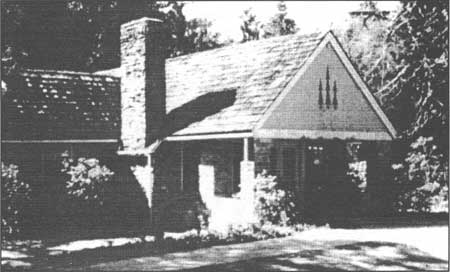

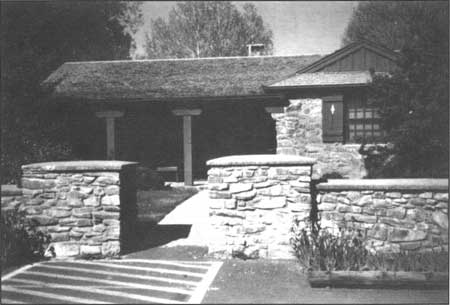

The administrative structures of Region 6 are not highly stylized log and stone buildings reminiscent of pioneer technologies, but are still distinctly rustic (figure 1-30). More refined, they are at the same time decorative and functional. The gable roofs, with pitch appropriate to climatic conditions, were the primary design, with variations such as hipped gables or gabled hips common. Porches, hoods, and dormers repeated the roof shape and trim. Roof materials were wood shingles or split shakes.

|

| Figure 1-30. Gold Beach Ranger Station Office (top) and residence. Siskiyou National Forest, Region 6 (1936). PHOTO BY LES JOSLIN |

Recreation structures were also constructed in Region 6. The Recreation Handbook, as revised in May of 1933, stated:

The Forest Camp should not take on the appearance of a museum or arboretum. Odd and contorted trees may be left, but we find that the average tourist wishes to see straight, healthy and vigorously growing trees and shrubs.

Rustic recreational architecture in the campgrounds developed by the CCC represented entirely new construction in most cases. For the children, some campgrounds afforded playground facilities designed by the Regional Office architects.

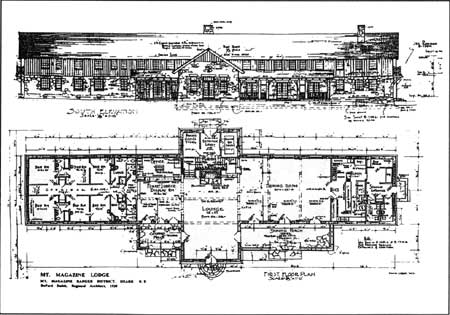

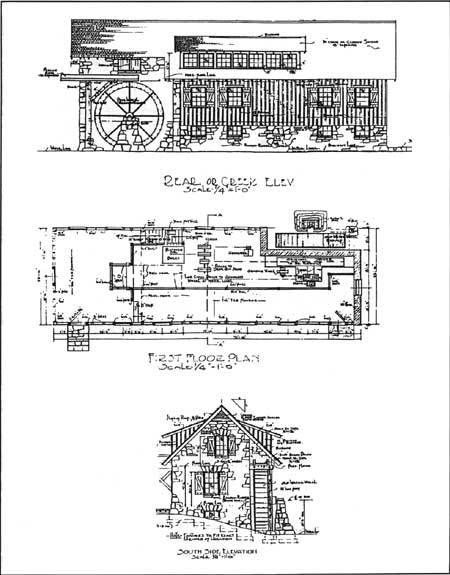

Region 8 hired DeFord Smith as Regional Architect in 1934. Smith was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania in architecture. He was very busy during the CCC era, producing 14 designs in 1934, 43 in 1935, 68 in 1936, 69 in 1937, 75 in 1938, and 64 in 1939. These designs consisted of picnic shelters, toilets, residences, offices, bunkhouses, lodges, and fire towers (see figures 1-37 and 1-38 on pages 46 and 47). He considered his most notable projects as Mt. Magazine Lodge (1939), Wayah Bald Observation Tower (1938) (see figure 2-74 on page 103), and various bridge designs for Puerto Rico.

Also in Region 8, the CCC razed "undesirable structures" such as cabins and outbuildings left by former owners or occupants to prevent their use by squatters. In later years, only a few foundation stones and bases for chimneys remained to mark the site of these former mountain homes.

Among the notable structural achievements in Region 9 was the building of the Chippewa National Forest Headquarters in 1935 (figure 1-31). CCC and WPA craftsmen constructed a Finnish-style notch-and-groove log building. This is considered the largest log building of its kind; it was made of native red pine and finished with other local materials. The 50-foot stone fireplace was constructed with glacial boulders collected from the nearby area. This structure is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

|

| Figure 1-31. Headquarters Building, Chippewa National Forest, Region 9 |

In Region 10, a significant Depression-era project was the Petersburg Ranger Station compound. When first requested in 1935, there was little hope of getting a Federal building for this small town in southeast Alaska. District Ranger J.M. Wyckoff aggressively pursued the project with other officials who needed office space. In the submittal to Congress, the Regional Forester noted, "It would be to our advantage to have a building which would also house the Customs Service Office, as it could during the Ranger's absence give the public information it might require . . ." Emergency Relief Act funds purchased a 50- x 100-foot corner lot for $650. A Colonial Revival style two-story, split-foyer office building and adjoining garage were designed and constructed by locally hired CCC members. Each floor of the wood-framed building was 24 x 28 feet. A semicircular wooden arch marked the entrance of the otherwise plain, square structure. [10]

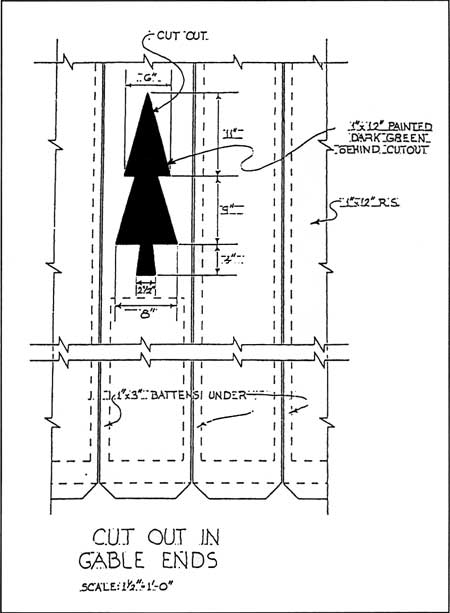

A common element in most of the buildings constructed by the CCC is the "pine tree" logo of the Forest Service and the Civilian Conservation Corps. Nationwide, the pine tree is found in many shapes, sizes, and forms on the buildings of that period. A good example is on the Gallop Ranger Station on the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest in Region 6 (figure 1-32). Because the pine tree symbol appears on structures in all Regions of the Forest Service, it seems certain that a directive suggesting its inclusion in design was issued from the Washington Office. The phenomenon is too widespread to be a regional innovation, and it is limited to Forest Service structures. Pine trees were cut from single boards or formed by silhouettes joined by two boards; sometimes they were cut from one board and applied to another (figure 1-33).

|

| Figure 1-32. Residence, Gallop Ranger Station. Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, Region 6 (1936) |

|

| Figure 1-33. The distinctive pine tree logo was a common element in most of the buildings constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps |

As end products of an important Federal response to the Depression, CCC constructions are associated with events that are significant in the Nation's history. Because they embody the distinctive characteristics of a period and type of construction, the rustic buildings on national forest lands are significant in American architecture; many exhibit excellence of design and possess high artistic values. Figures 1-35 through 1-41 show additional examples of the buildings built during this era.

Forest Service Buildings of the CCC Era

|

| Figure 1-34. Warren Guard Station, Payette National Forest, Region 4 (1934). PHOTO BY LES JOSLIN |

|

| Figure 1-35. Bly Ranger Station Office, Fremont National Forest, Region 6 (1936) |

|

| Figure 1-36. Crown King Ranger Station barn and shop, Prescott National Forest, Region 3 (1936) |

|

| Figure 1-37. Mt. Magazine Lodge, Ozark National Forest, Region 8 (1939) |

|

| Figure 1-38. Blanchard Springs Mill, Ozark National Forest, Region 8 (1938) |

|

| Figure 1-39. Standard ranger office and quarters, Region 3, designed in the Spanish style |

|

| Figure 1-40. Standard ranger office and quarters, Region 3, designed in the bungalow style |

In 1940, Ellis Groben, in Architectural Trends of Future Forest Service Buildings, attacked what he felt was "the inappropriate practice of designing buildings which did not work well in [floor] plan, but were accepted and even praised because their exteriors blended well with the environment." Though not abandoning his stance on the appropriateness of regionally responsive design, Groben called for more creativity in formulating, where appropriate, a style uniquely representative of the Forest Service.

When the declaration of war was issued in late 1941, the CCC crews were quickly inducted into the armed services. The program soon became history as the need for a make-work program diminished and the full focus of the Nation was put toward defeating the Germans and Japanese.

Shortly after the United States entered the war, it became apparent that much more natural rubber would be needed than might be available. Because of the demonstrated ability of the Forest Service to organize and handle emergency procedures, the Forest Service was selected to handle the guayule rubber project in the Southwest. Guayule, resembling sagebrush, was a natural shrub in this area, containing up to 20 percent natural rubber. [11]

A major part of this project was the design and construction of labor camps, and a large number of nurseries were set up to grow the guayule plants from seed to seedlings. Jim Byrne, then Regional Engineer in California, was named chief engineer for the project. He called together architects from Regions 1, 5, 6, and 9. Clyde Fickes from Region 1 was in charge with Harry Coughlan, also from Region 1, Keplar Johnson from Region 5, Gif Gifford from Region 6, and Nels Orne from Region 9 along with many support people who produced the plans and supervised the construction. Until the end of the war, when the project was disbanded, much of the focus of the Forest Service architects was designing and constructing the infrastructure for growing guayule plants. At the end of the war, two rubber extraction plants were operating, and plans were on the table for four more extraction plants. Approximately 6 million pounds of rubber were dispatched to rubber processing plants by the war's end.

At the end of the war, all of the architects named above returned to their previous positions as architects in the Regions. All but Harry Coughlan were Regional Architects. Harry became Regional Architect in Region 1 shortly after the end of the war.

Notes

1. Throop, Utterly Visionary and Chimerical: A Federal Response to the Depression—An Examination of Civilian Conservation Corps Construction on National Forest System Lands in the Pacific Northwest, p. 7.

2. Schneck and Hartley, Administrating the National Forests of Colorado, p. 60.

11. USDA Forest Service, The History of Engineering in the Forest Service, p. 6.

1946-Present: The Modern Period

After the war, there were many changes in the focus and organization of the Forest Service. One was an increase in recreational use of national forest land, which led to a renewed emphasis on facilities construction, including campgrounds, restrooms, boat ramps, and trails. In 1947, 25 percent of the maintenance and improvement dollars were authorized for recreation improvements. The architects who had been working on the guayule project returned to their regional positions and started hiring new, younger graduate architects.

The era of handcrafted construction ended with the disbandment of the CCC. Attention shifted toward postwar plans for expansion. Projects in progress before 1942 were completed, but construction of new improvements had been halted by the war. Shifts in the use of the forests resulted in changes in administrative methods; some permanent ranger stations became "work centers," a new term coined to replace the outdated "guard station," which had acquired the wrong connotation during the war.

Regional Architects

The following paragraphs provide a brief outline of individuals who served as Regional Architects during this period. See Chapter 3, People, for more detailed information on the design styles of contributing architects.

At the start of 1946, Regions 2, 3, 7, and 8 did not have Regional Architects. This void remained in some Regions until the end of the 1950's or later.

In Region 1, Clyde Fickes left the Forest Service before the end of the war, and Harry Coughlan took over the position of Regional Architect. Most of the work just after the war was custodial, bringing the many buildings and stations that had been neglected back to standard and correcting safety hazards. The need for additional staff did not occur until the early 1950's, when Congress enacted legislation to provide improved and additional recreational facilities. Art Anderson was the first professional hired in Region 1 after the war, and he took over as Regional Architect when Coughlan retired in 1965. In 1972, Bob LeCain became Regional Architect and Anderson took over as administrative and planning leader. When LeCain retired in 1985, Dave Dodson took over the position and remained until 1990. Josiah Kim was the Regional Architect from 1990 to 1997.

In Region 2, W. Earle Jackson departed sometime in 1942 and the Regional Architect's position was not filled until Wes Wilkison was hired in 1958. When Wilkison retired in 1981, Dave Faulk became Regional Architect.

Region 3 did not have a Regional Architect of record until George Kirkham was hired in the mid 1960's. George Nichols did building designs for the Region from Ogden during the CCC era. After Kirkham left, Lou Archambault took over the position. Soon after, Hal Miller transferred from Portland to become Regional Architect. In the early 1990's, Kurt Kretvix became Regional Architect.

George Nichols in Region 4 was not part of the guayule project. There are no records during the war years to indicate whether he went into the military or just continued working for the Forest Service. In 1946, he was listed as the Regional Architect. William Turner was hired in 1958 to assist in the design work and took over as Regional Architect when Nichols retired. When Turner retired, Wilden Moffett took over the post of Regional Architect.

Keplar Johnson returned to his position as Regional Architect in Region 5 after the guayule project. Like most American architects, he was increasingly influenced by the modern movement in architecture after World War II. In several of his postwar buildings, Johnson continued the design themes that had marked the Region's building program of the 1930's. But even in these structures, Johnson was influenced by the ideas of the modern movement. Johnson revised many of Blanchard and Maher's plans and designed a number of new plans for specific sites within the Region.

After Johnson's retirement in 1962, Harry Kevich was named Regional Architect. Kevich increased the architectural staff by hiring young architects just out of college. He played a more managerial role and delegated most of the design work to this staff. They developed a more contemporary, modern style building for the California Region. Bob Sandusky became Regional Architect upon Kevich's retirement in 1985.

Tim Turner continued as Regional Architect in Region 6 during the war years, and he continued to work until a heart attack caused an untimely death in 1951. A.P. "Benny" DiBenedetto was hired to replace him from the Army Corps of Engineers. When DiBenedetto took over as Research Architect for the Pacific Northwest Station, Ken Reynolds was named Regional Architect. When Reynolds left, Joe Mastrandrea served as Regional Architect. JoAnn Simpson was Mastrandrea's successor.

Region 8 was without a Regional Architect from 1942, when DeFord Smith departed, until 1968, when William Speer was hired. Because there was no lead architect in Atlanta, Speer went to San Francisco to serve an apprenticeship under Harry Kevich and John Grosvenor. Speer spent a year working in Region 5, doing the designs for Region 8, before returning to Region 8 to continue as Regional Architect.

Nels Orne returned from the guayule project in 1945 and continued as Regional Architect in Region 9, where he worked until his appointment to Branch Chief for Facilities in 1965. His successor was Jim Calvery from Region 5. Upon Calvery's retirement, Dave Dercks was named Regional Architect.

Shortly before World War II, Linn Forrest transferred to Juneau to serve as the first Regional Architect for Region 10. His tenure did not last very long, as he and his son opened a private practice in Juneau in 1952. After Forrest left, George Danner, a technician, provided leadership in the design and maintenance of buildings until his retirement. At this time, there is no professional architect in Region 10.

Projects

In 1952, improvement projects nationwide were focused on rehabilitation, relocation, replacement, or reconstruction of older facilities. The Chiefs message again emphasized the need for prior approval for construction projects to ascertain whether the project was essential to efficient program operation. In the mid-1950's, funding for construction remained low—only $100,000 was available nationwide. The following years were characterized by continued decentralization, specialization, and increasing workloads for rangers and staff. Forest engineers bore the responsibility of overseeing improvement programs on individual forests.

The early 1960's ushered in another era in Forest Service administration that demanded an architectural response. New "make work," educational. and other social economic programs brought accelerated public works, Job Corps, prison labor camps, Youth Conservation Corps, and other programs to the national forests. These work programs provided educational opportunities, vocational training, and practical skills in construction and other forestry activities for young and unemployed people. Congress allocated enormous funding for these and similar programs, which brought the Forest Service a huge influx of design and construction projects (figure 1-41).

|

| Figure 1-41. Trapper Creek Job Corps Center, Bitterroot National Forest, Region 1 (1965) |

In the 1970's, the emphasis turned to clean water. Water pollution abatement brought the Forest Service many millions of dollars to provide modern campgrounds and sewer systems to serve recreational and administrative sites. Since the early 1960's, the architectural staffing in the Regions had grown to be equal to or greater in size than that of the CCC era. About this time, there was a reduction in Job Corps centers in several Regions (California, for example, went from five centers to none). As of this date, there are still six centers in Region 8 as well as centers in Regions 1, 2, and 6.

Forest Service Research relied on the Regions to provide the design and maintenance of the buildings on the experimental forest and station headquarters and laboratories. A.P. "Benny" DiBenedetto was the first professional architect hired on staff to do the designs for the Pacific Northwest Experiment Station in 1961. Bob Sandusky was hired by the Pacific Southwest Station in 1965. The other research stations continued to rely on the Regions or private architectural firms for their building designs. The North Central Station is the only research station that still has an architect on staff.

Beginning in the 1960's, the architectural staffs in the Forest Service took on a more philosophical design approach rather than concentrating on specific styles or themes. Contrary to Groben's dictates of the 1930's, architects produced designs that fused the modern with the vernacular of the past, seeking designs appropriate for the forest environment and comparable with the existing buildings on the sites.

Some of the new, innovative programs and projects like the Job Corps, accelerated public works, the Clean Water Act, and visitor centers have allowed the Regions to hire additional architectural staff. In addition, cooperative work with other agencies has allowed additional use of recently graduated architects.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

EM-7310-8/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 08-Jun-2008