A History of the Architecture of the USDA Forest Service

|

|

Chapter 2

Building Types

"The fate of the architect is the strangest of all. How often he

expends his whole soul, his heart and passion, to produce buildings

into which he himself may never enter."

—Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Elective Affinities

Administrative Buildings

The category of Forest Service buildings with the greatest number and

most diverse types is administrative buildings. These cover all areas of

work and living needs. Lookout towers are part of this group, but will

be covered separately. Administrative buildings include offices,

dwellings, barracks, messhalls, bunkhouses, warehouses, shops, fueling

stations, and nursery buildings. Architectural styles tend to fall into

eras, location within the Nation, and local trends and materials

available. There is more consistency within each site, at least

regarding materials.

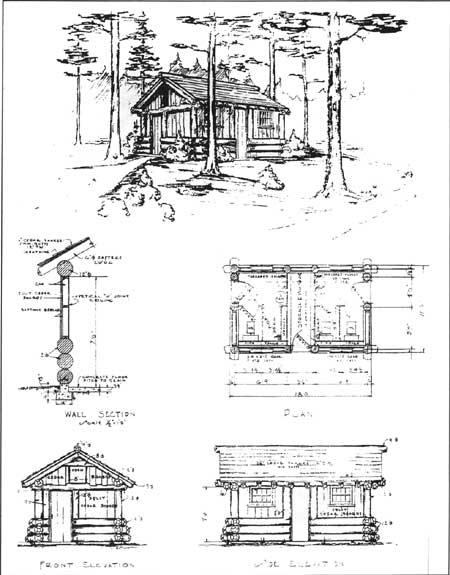

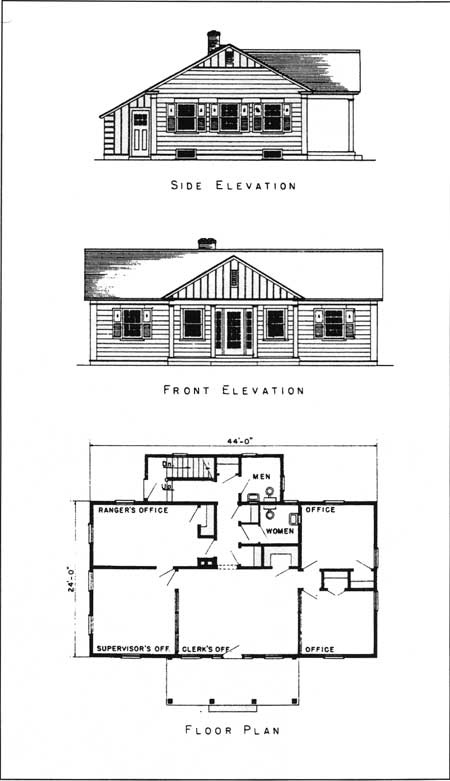

In the earlier eras, the plan layout for buildings was limited by

availability of designers and the buildings' functions. Most of the 1938

"Acceptable Plans" book covered administrative buildings, giving many

floor plans and various elevation styles. As the first Service-wide

compilation of this type, most of the Regions used it only as a starting

point for their designs and did not copy the individual buildings.

There is more continuity within the various Forest Service Regions

throughout the eras than there is between Regions during an era. Traced

to climate, local materials available, and overlap of personnel between

the eras, this can be seen in the regional plans and elevations shown in

the 1938 "Acceptable Plans" book. Another difference between Regions is

the year the first architect was brought on staff.

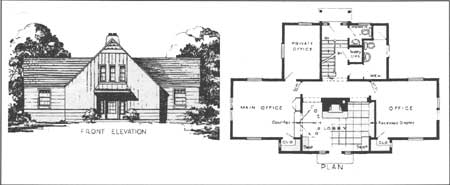

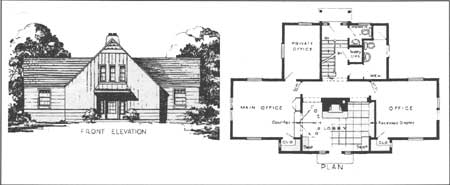

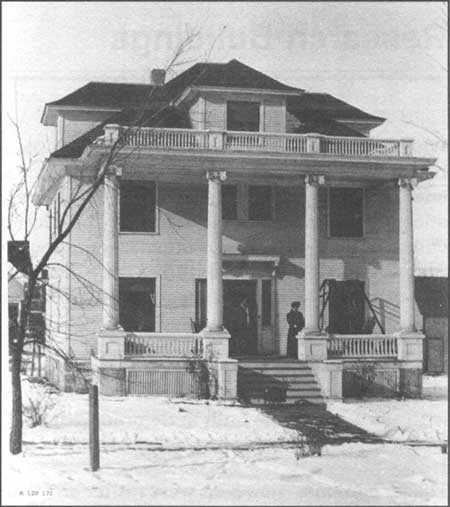

Offices

Through the various eras, the need for and the size of office buildings

has changed tremendously. At the start, Forest Service contact with the

public was limited and a small room rented in the nearest town was

sufficient. It was not until the 1930's that buildings with the primary

use of office space and public contact were required and constructed.

Even then they were one to four rooms located in the nearest town to the

forest land being managed. After World War II until the 1970's, the

largest district offices had only 5 to 15 rooms, but with a better

public contact area. Supervisors' offices during the 1930's and 1940's

were smaller than district offices in the 1980's.

The design and styles of offices follow the regional styles and eras

described in chapter 1. Not until the modern era were the differences

between Regions dependent upon who was the design architect rather than

the direction of the agency. Once the "Acceptable Plans" book went out

of favor and there was no architect in the Washington Office, the

Regions began to establish their own design style (sometimes even within

a Region there were State styles). There was still a predominant use of

wood with pitched rather than flat roofs, but as we approach the present

day, more and more of the materials conform to the regional standards.

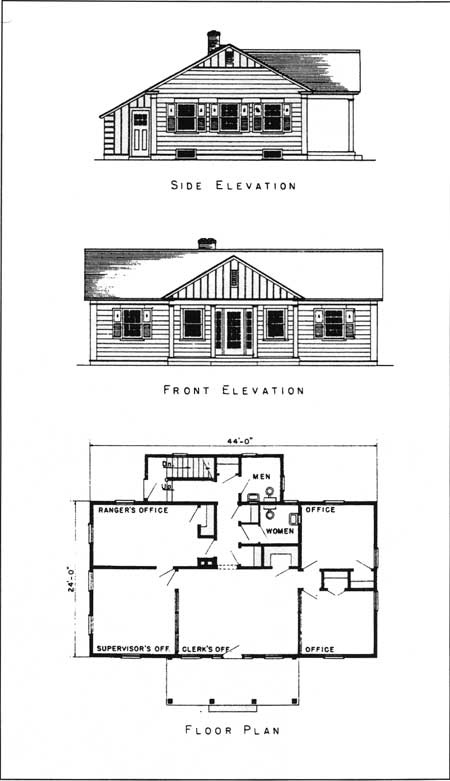

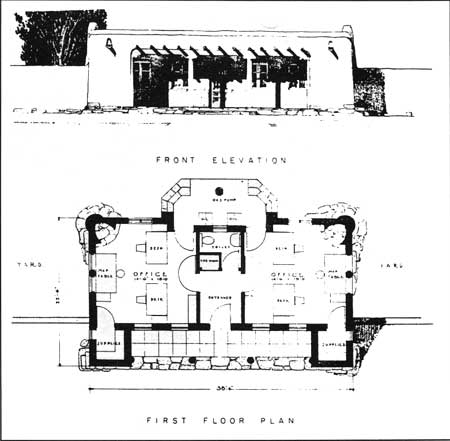

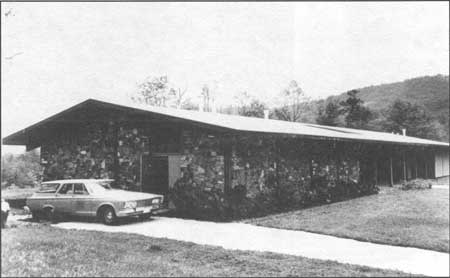

Figures 2-1 and 2-2 and the photos and drawings on pages 68

through 80 show these variations in design and style.

|

|

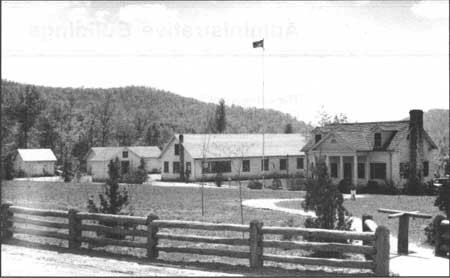

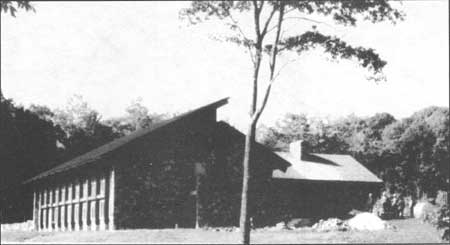

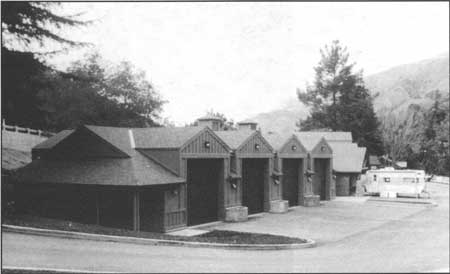

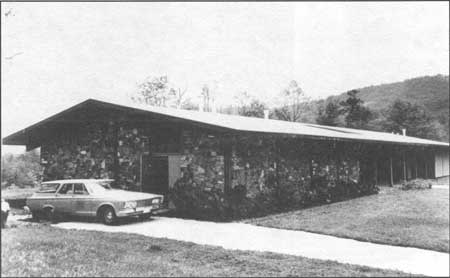

Figure 2-1. Blue Ridge Ranger Station Office and warehouse,

Blairsville, Georgia

|

|

|

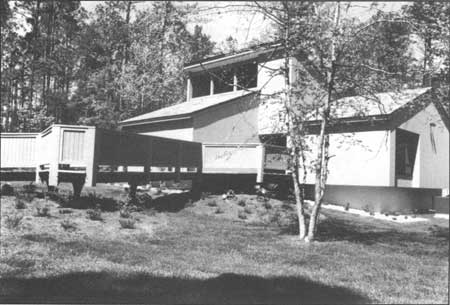

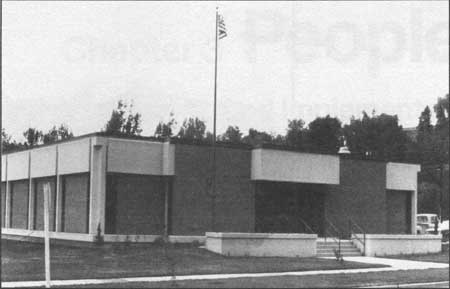

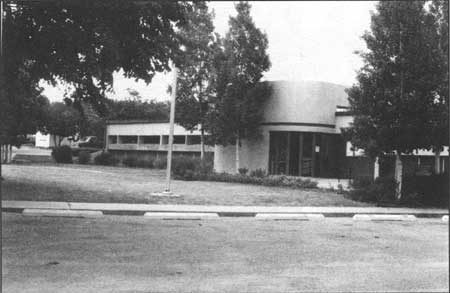

Figure 2-2. Groveland Ranger District Office, Groveland

California, Region 5 (1991)

|

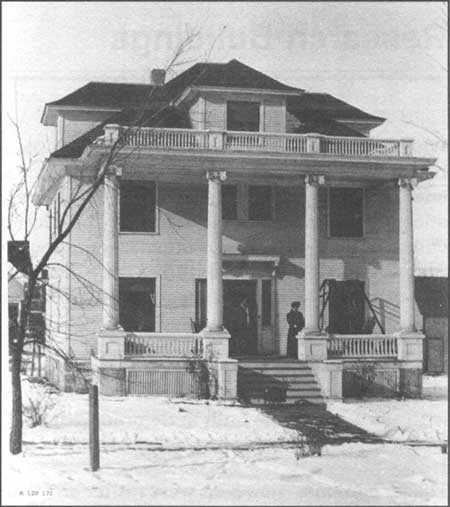

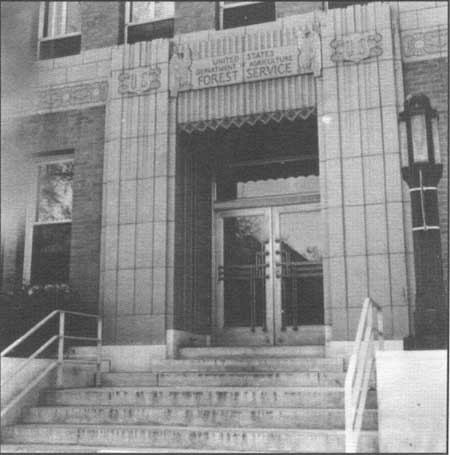

The only Regional Office designed and constructed by the Forest Service

is in Ogden, Utah (figures 2-3 and 2-4). George Nichols, the

newly hired Regional Architect for Region 4, was given the task to

develop plans for a Government-owned structure when the leased office

first occupied in 1909 became inadequate. He presented his concept for a

square four-story building near the center of town to the Regional

Forester in October 1928. After submission upward, Senator Reed Smoot of

Utah came to Ogden. He agreed that the Forest Service should remain in

Ogden and stated that he would support the

new office. He passed this information on to the Treasury Department,

then responsible for Federal buildings. They sent W. Arthur Newman,

District Engineer, Treasury Department Field Force, Office of the

Supervising Architects, San Francisco, California, to Ogden to make a

study of the leased building occupied and the plans developed by

Nichols. Newman went through the entire building with Nichols and the

Regional Forester and agreed with the Forest Service proposal.

|

|

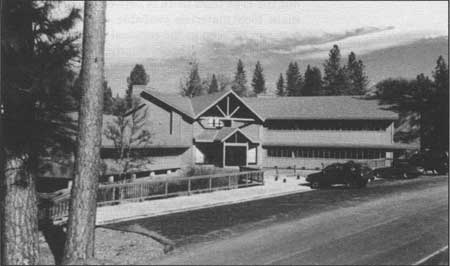

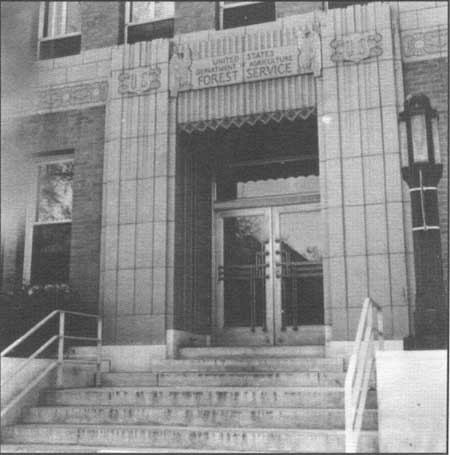

Figure 2-3. Region 4 Office, Ogden, Utah (1933)

|

|

|

Figure 2-4. Entrance detail, Region 4 Office

|

The Second Efficiency Bill, which passed both houses of Congress in

February 1931 and was subsequently signed by the President, included

$300,000 for the building. As with many political issues, along with the

appropriation of dollars came directions from above. In this case a

local architectural firm, Hodgson-McClenahan, was given the

responsibility for preparing the final contract documents, using much of

what Nichols had recommended and documented. The final building was a

brick and terra cotta Art Deco structure, three stories of offices with

a basement and a greenhouse on the roof.

The construction contract was awarded to Murch Brothers of St. Louis for

$229,000. The National Lumbermen's Association wrote a letter objecting

to the design and requesting a greater utilization of wood in the

construction of the building. Several changes were made: wood piling,

wood frames and sashes on the first floor, hardwood floors (oak) for all

offices, wood bases, and wood trims on the first floor.

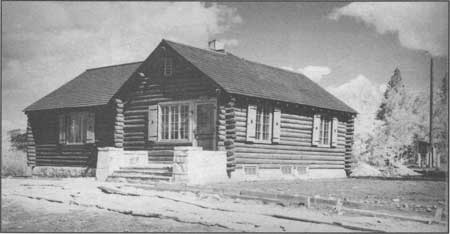

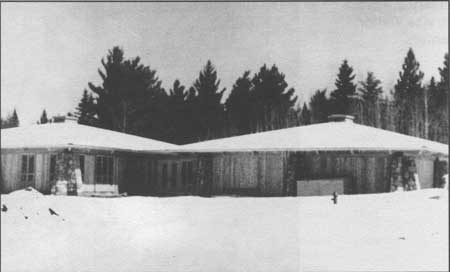

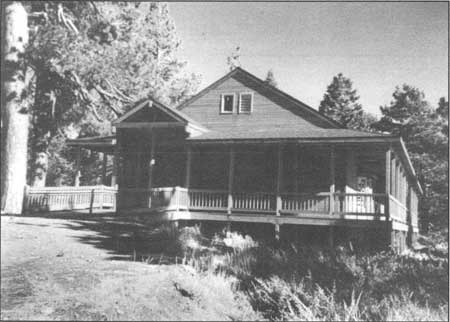

Housing

Provision for housing of Forest Service employees has been a need since

the earliest days. Tents and lean-to's to log cabins were the prevalent

housing during the first era of the agency. Later, when families stayed

with the rangers and offices were set up in town, more sophisticated

dwellings were built on the same compound as the office and warehouse or

storage area or near them on another lot (figure 2-5).

|

|

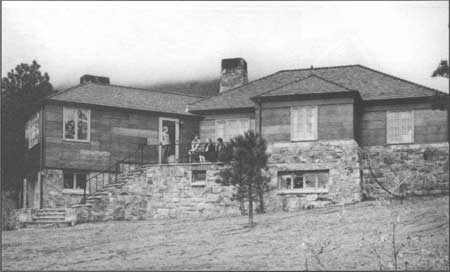

Figure 2-5. Ranger Residence, Pestigo Ranger Station, Nicolet

National Forest, Region 9 (1936)

|

When fire suppression and timber

sales became part of the administration of the National Forests, there

came a need for housing for crews. Early barracks were just residences

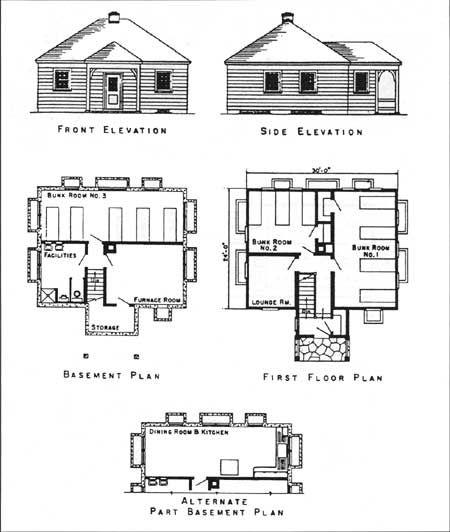

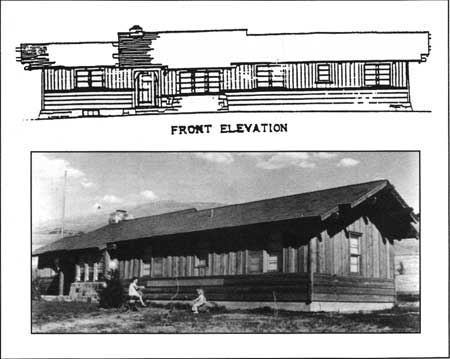

with extra bedrooms and a larger kitchen and dining room. In the 1930's,

crews were larger and totally male, so the housing for crews included

bunk rooms, lounges, large bath facilities, and kitchen and dining areas

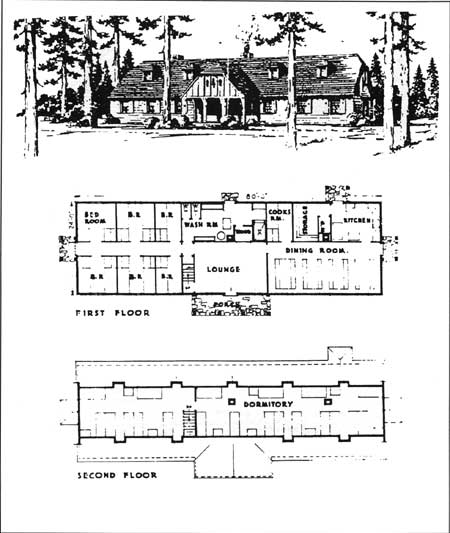

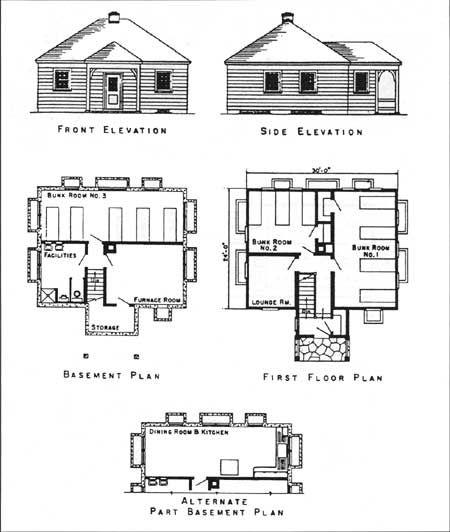

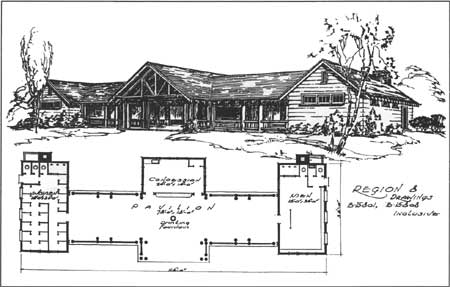

(figures 2-6 and 2-7).

|

|

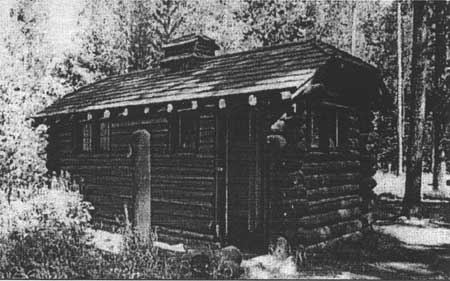

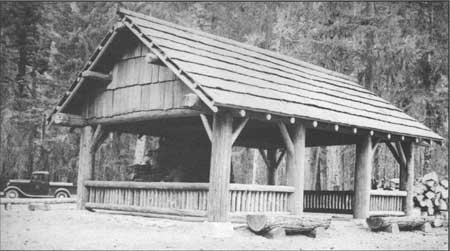

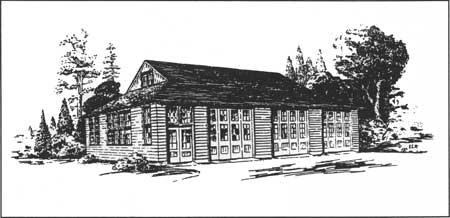

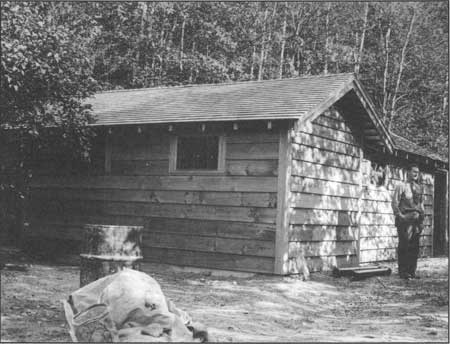

Figure 2-6. Bunk house, Region 1

|

|

|

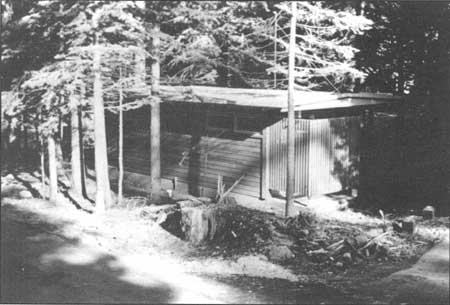

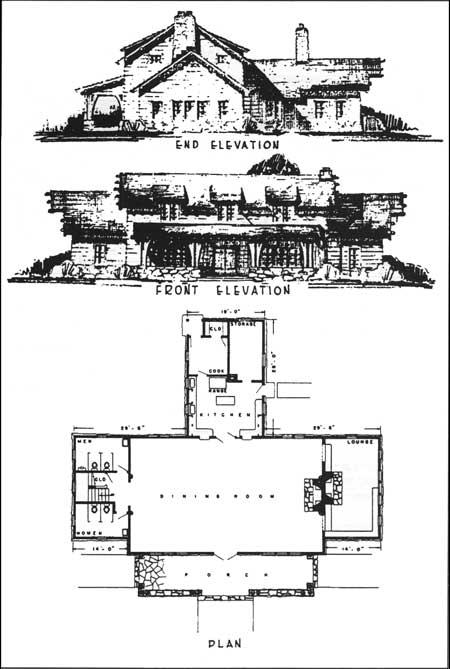

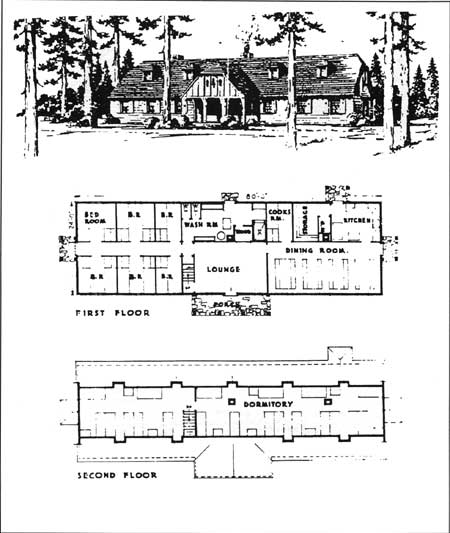

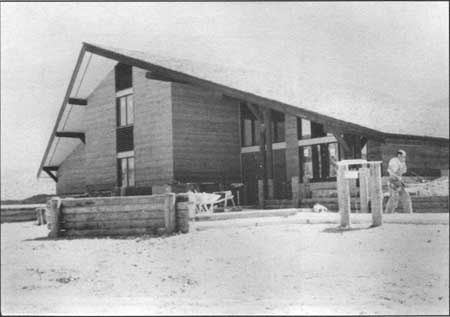

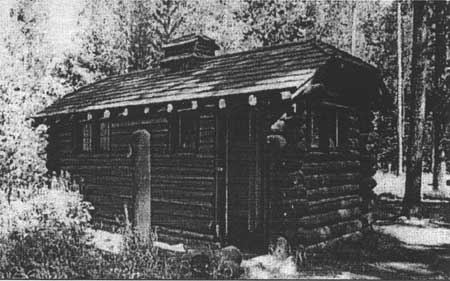

Figure 2-7. Thirty-person crew house, Region 6

|

There was very little change in single-family dwellings and crew

quarters during the next 30 years except for materials and styles based

on the Region. In the 1960's, several changes created different design

approaches. First, the crews became larger and more diversified (fire,

timber, recreation, lands, wildlife, and so forth) and worked in the

field in different seasons. The buildings took on a character of either

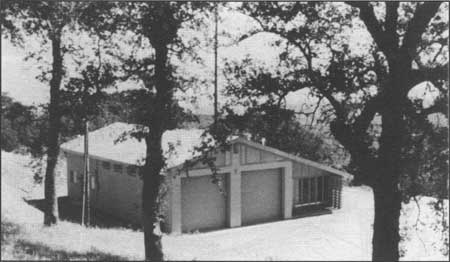

meeting the needs of a special workgroup such as a fire crew (figure

2-8), or the crews were housed in separate smaller buildings (see

figures 2-40 and 2-41 on page 81 for some examples). Another

trend during this phase was the use of trailers as portable camps that

would follow the work. In California, one forest had more than 100 small

trailers that were taken to the field in the spring and stored at lower

elevations during the winter.

|

|

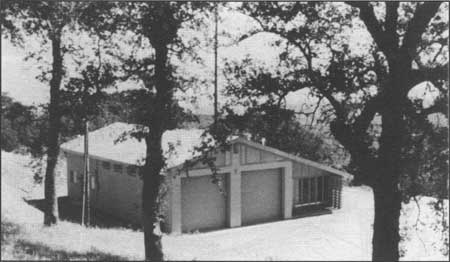

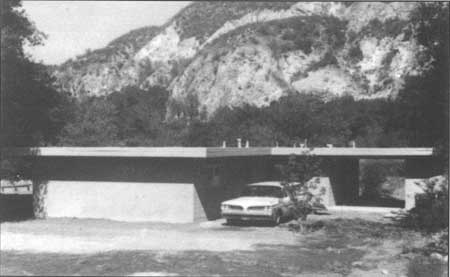

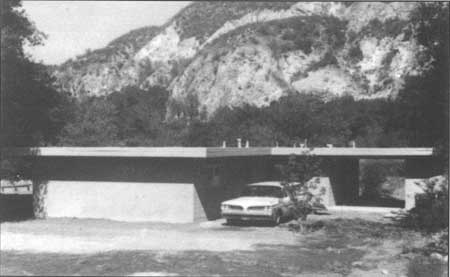

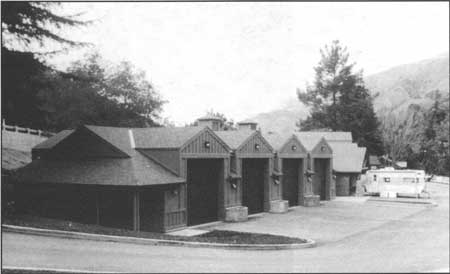

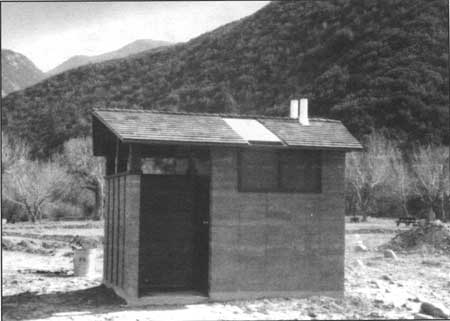

Figure 2-8. White Oaks Fire Station, Los Padres National Forest,

Region 5 (1967)

|

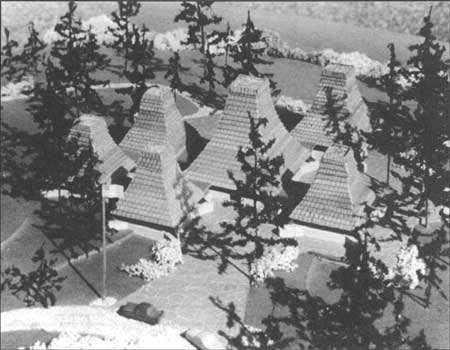

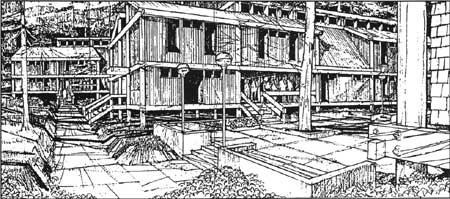

When the Job Corps was founded during the Johnson Administration, the

Forest Service was one of the major players in providing space and work

for this new venture. The first centers were trailers or modular

structures purchased under Department of Labor design standards. Because

there were so many being started at the same time, long delays in

delivery were encountered, so the various Regions went into a crash

design program to construct stick-built structures for the centers. Many

of the trailers did not last very long. Region 5 and the Bureau of

Reclamation in Denver were given the task of

designing replacement buildings for these damaged trailers. A concept

of pole buildings was developed for housing and dining facilities

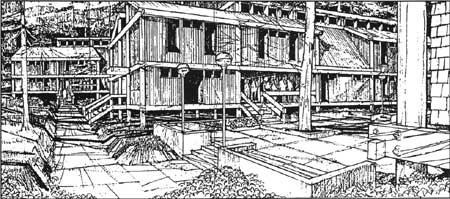

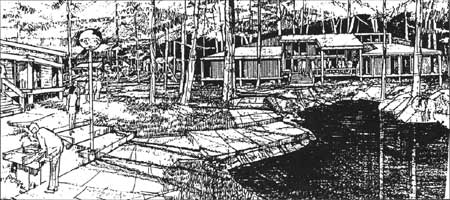

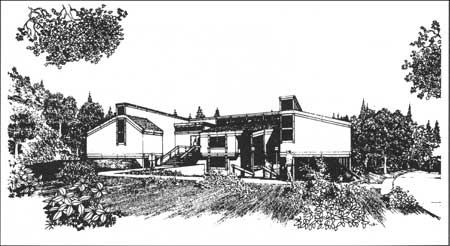

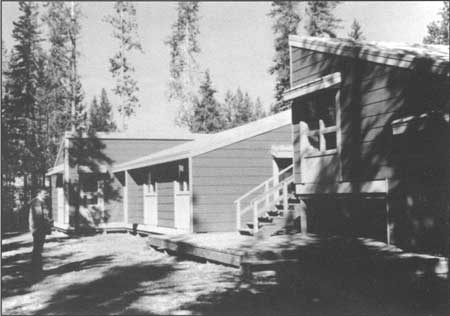

(figures 2-9 and 2-10). The architects in California were

given Certificates of Merit by Chief Ed Cliff for their work (see figure

3—15 on page 216).

|

|

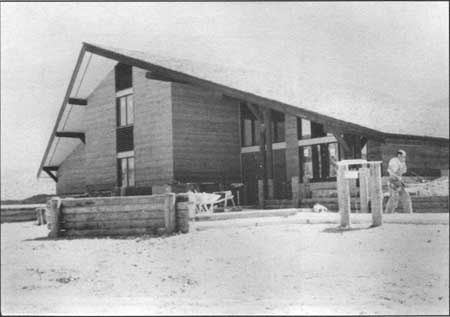

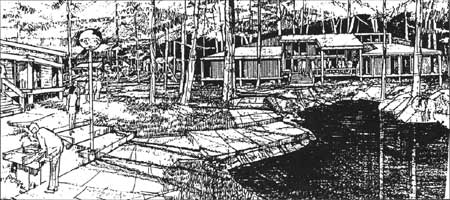

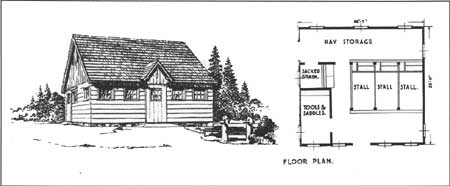

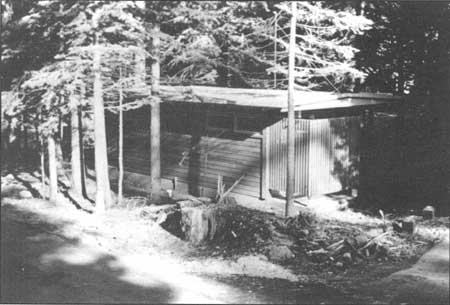

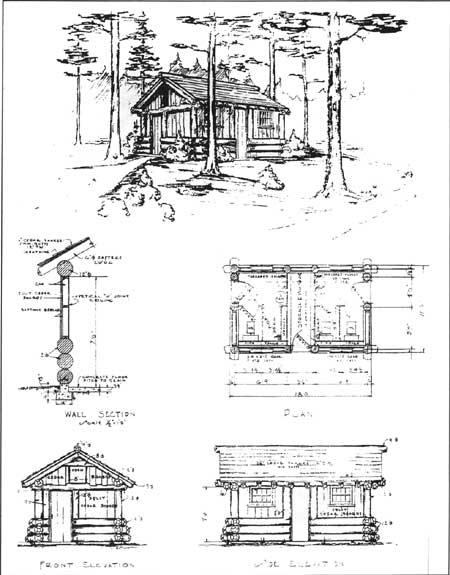

Figure 2-9. Concept for Job Corps dormitories

|

|

|

Figure 2-10. Concept for Job Corps kitchen and messhall

|

Warehouse and Storage Facilities

Few of the Forest Service warehouse and storage facilities are unique to

the agency. As with any organization that provides its own facilities to

cover all administrative activities, many diverse building types are

needed. During most of its history, the Forest Service has owned a fleet

of automobiles and trucks; therefore, the need for autoshops has been a

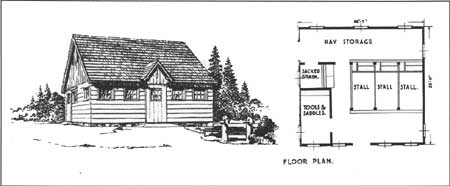

necessity (figure 2-11). Also, since many of the areas administered

are in the mountains, horse and mule barns, including hay storage, have

been needed (figure 2-12). Warehouse and storage buildings have

been needed for firefighting supplies and equipment, recreation,

operation and maintenance, and timber management, as well as for other

specialized forest management activities. Additional examples of

warehouse and storage building designs can be found in Figures 2-56

through 2-60 on pages 89 to 91.

|

|

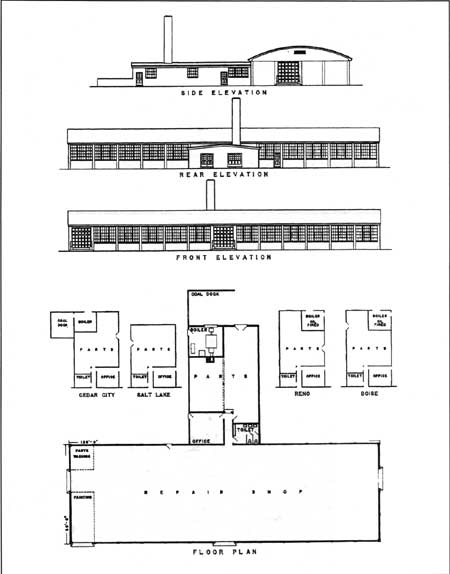

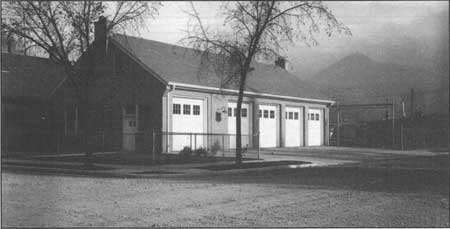

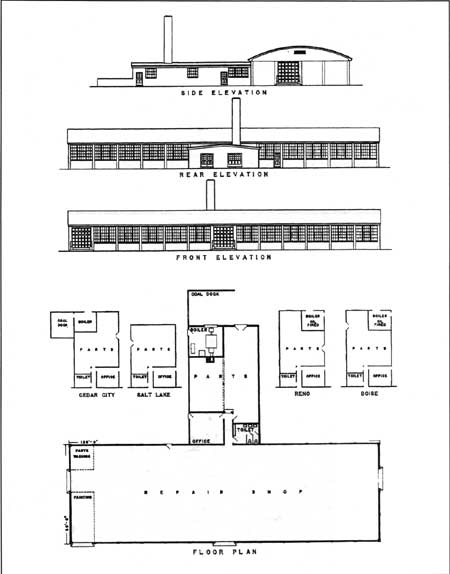

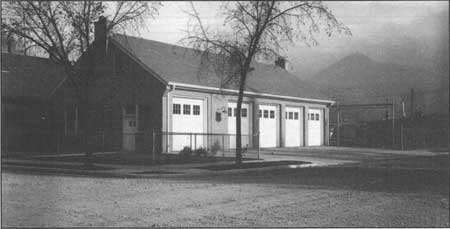

Figure 2-11. CCC Central Repair Shop, Region 6

|

|

|

Figure 2-12. Three-horse barn, Region 6

|

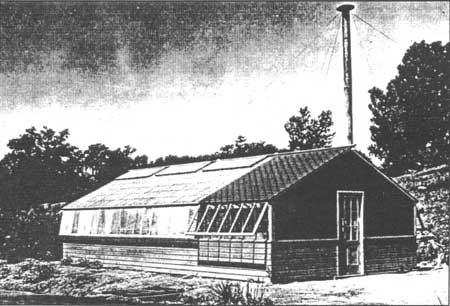

Nursery Buildings

Sometime in the early 1900's, the Forest Service started a tree planting

program to regenerate the forests after tree harvesting and fires

(figure 2-13). The buildings required for these

processes—germination of seeds, packing of seedlings after lifting

from growing beds, storage of seedlings until planting, and so

forth—provided challenges to the designers and architects. Examples

of successful nursery building projects include the administration

building at the Savenac Nursery in Region 1 (figure 2-14). The Savenac

Nursery has operated continuously since it was established in 1909 near

Haugen, Montana.

|

|

Figure 2-13. Western yellow pine beds, McCloud Nursery, Shasta National

Forest, California (1914)

|

|

|

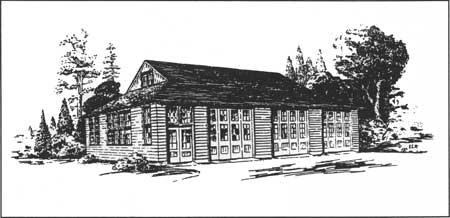

Figure 2-14. Administration Building, Savenac Nursery,

Region 1

|

A tree storage building at the Mt. Shasta Nursery in California designed

in the early 1940's had 12-inch-thick walls filled with redwood bark to

keep the trees in a dormant state from November until planting in April

or May of the next year. Another cold-storage building can be found at

the Placerville Nursery (see figure 2-15). The most recent nursery

complex designed and constructed was in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in the

mid-1980's.

|

|

Figure 2-15. Cold Storage Building, Placerville Nursery,

Region 5 (1980)

|

Gallery of Forest Service

Administrative Buildings

Offices

|

|

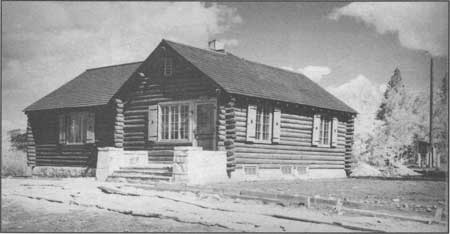

Figure 2-16. Minarets Ranger District Office, Sierra National Forest,

California

|

|

|

Figure 2-17. Brush Creek Office, Grand Mesa National Forest,

Region 2 (1936)

|

|

|

Figure 2-18. Office Building, Region 4

|

|

|

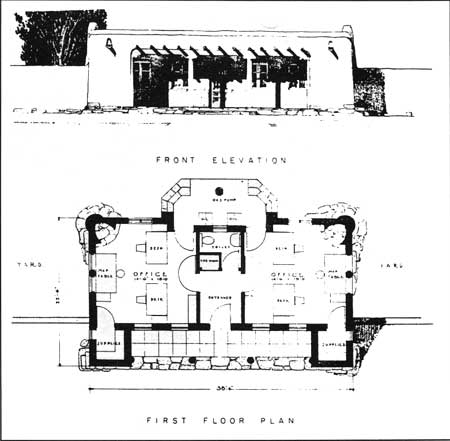

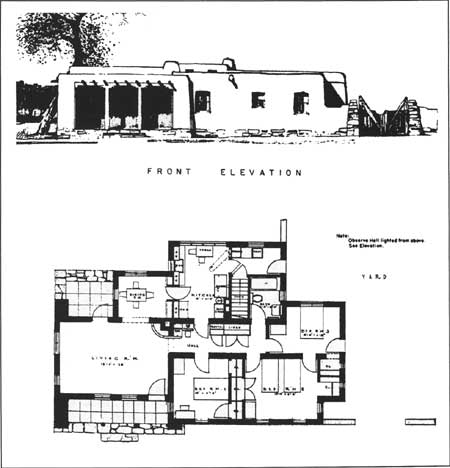

Figure 2-19. Magdalena-Augustine District Office, Cibola National

Forests, Region 3 (1938)

|

|

|

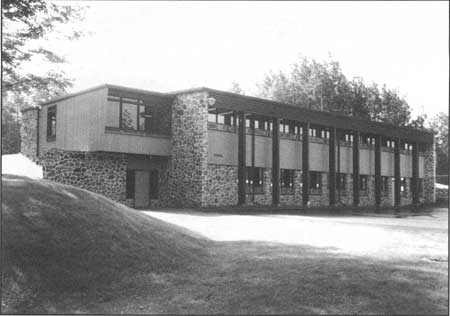

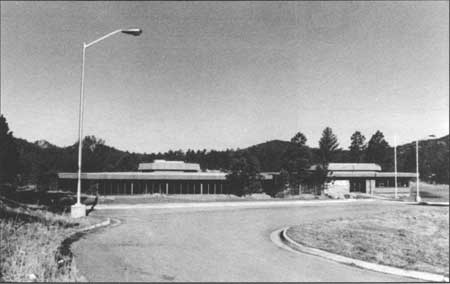

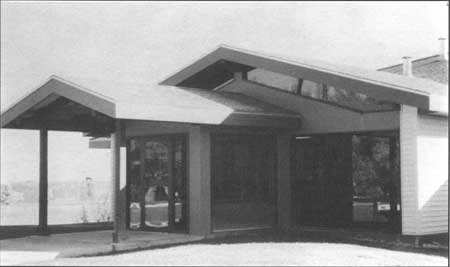

Figure 2-20. Quilcene Office, Olympic National Forest, Region 6 (1968)

|

|

|

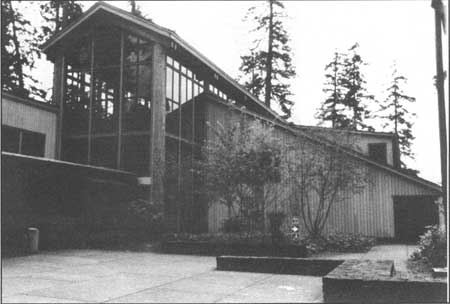

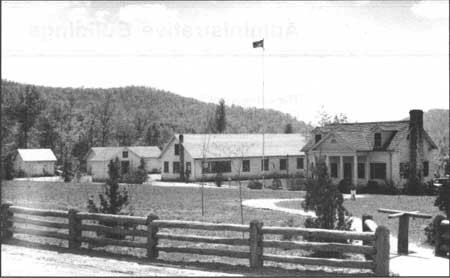

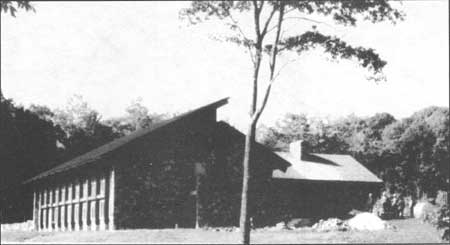

Figure 2-21. Quinault Ranger Station, Olympic National

Forest, Region 6 (1974)

|

|

|

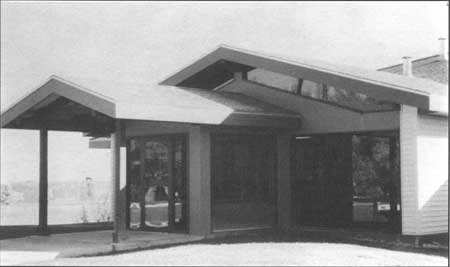

Figure 2-22. Big Sur Multiagency Office, Los Padres

National Forest, Region 5 (1989)

|

|

|

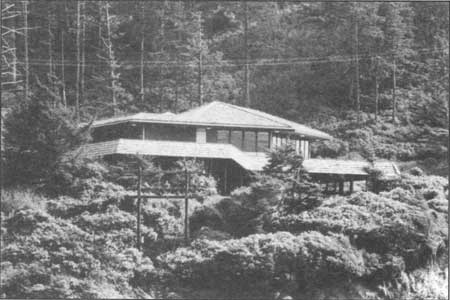

Figure 2-23. Hebo District Office, Siuslaw National

Forest, Region 6 (1972)

|

|

|

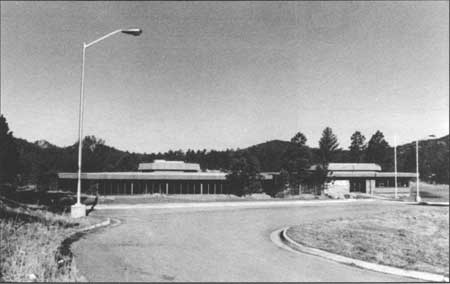

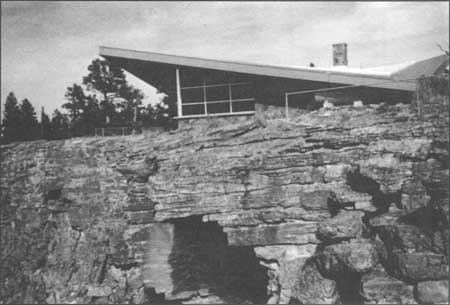

Figure 2-24. Black Hills National Forest Supervisor's Office,

Custer, South Dakota, Region 2 (1980)

|

|

|

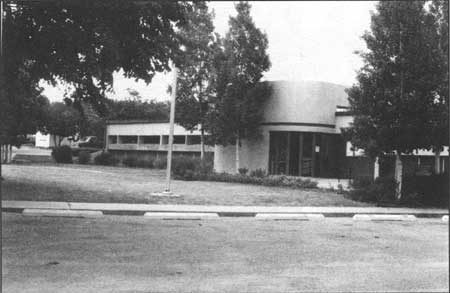

Figure 2-25. Plumas National Forest Supervisor's Office,

Quincy, California, Region 5 (1962)

|

|

|

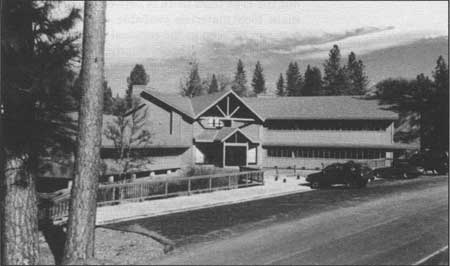

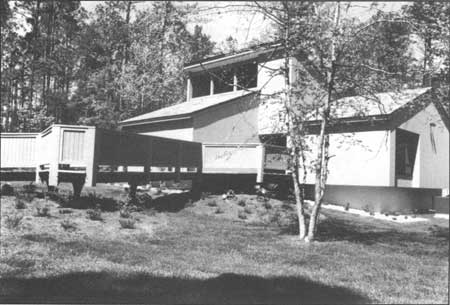

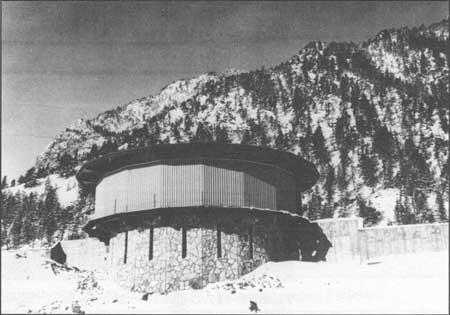

Figure 2-26. Sawtooth National Recreation Area Ranger

Office, Ketchum, Idaho, Region 4 (1978)

|

|

|

Figure 2-27. Pecos Ranger Station, Santa Fe, New Mexico,

Region 3 (1994)

|

|

|

Figure 2-28. Supervisor's Office, Bridger-Teton National

Forest, Region 4 (1966)

|

|

|

Figure 2-29. Mount Roger's Ranger Office, Jefferson

National Forest, Region 8

|

|

|

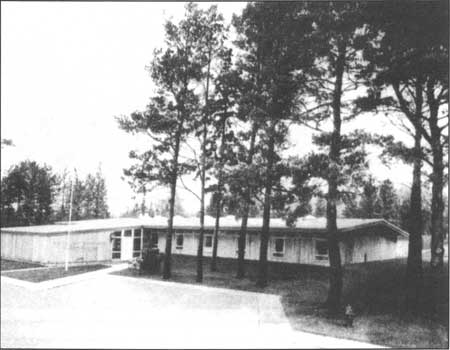

Figure 2-30. Tuskegee Ranger Office, National Forests of

Alabama, Region 8

|

|

|

Figure 2-31. Sanpete District Office, Manti-LaSal National

Forest, Region 4 (1944)

|

|

|

Figure 2-32. Entrance detail, Sanpete District Office, Manti-LaSal

National Forest, Region 4 (1994)

|

|

|

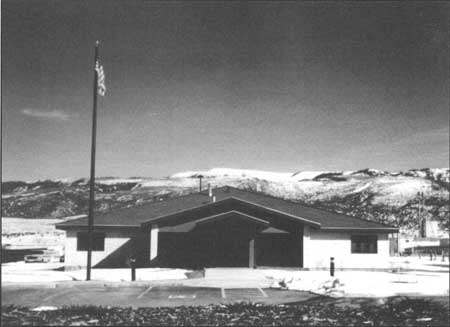

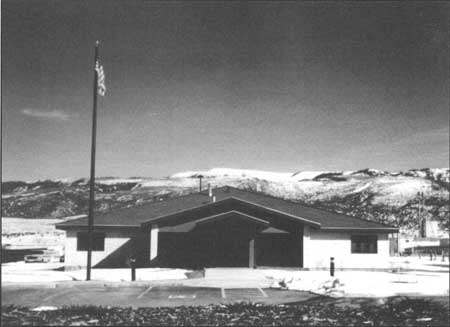

Figure 2-33. Lost River District Office, Challis National Forest,

Region 4 (1983)

|

|

|

Figure 2-34. Wise River Ranger Office, Beaverhead National

Forest, Region 1 (1982)

|

|

|

Figure 2-35. Box Elder Job Corps Center Office, Region

2 (1974)

|

|

|

Figure 2-36. Catalina Ranger Office, Caribbean National

Forest, Region 8 (1980)

|

|

|

Figure 2-37. Saguache Ranger District Office, Rio Grande

National Forest, Region 2 (1985)

|

|

|

Figure 2-38. Bienville Ranger Office, Bienville National

Forest, Mississippi, Region 8 (1980)

|

|

|

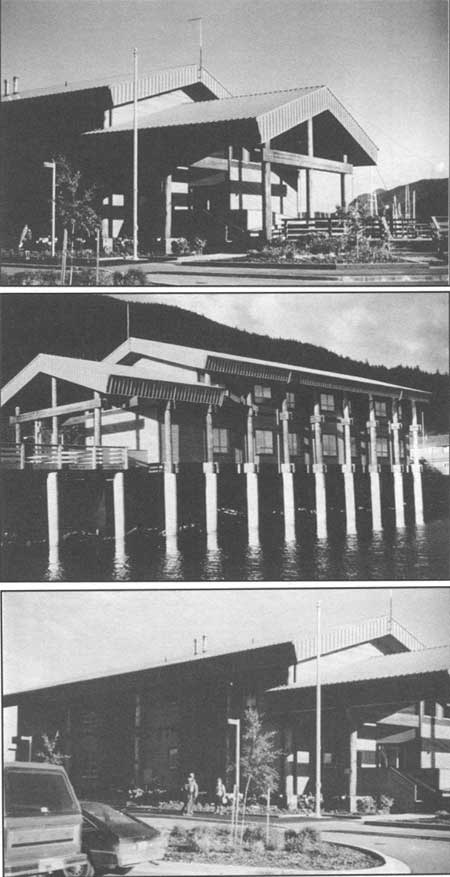

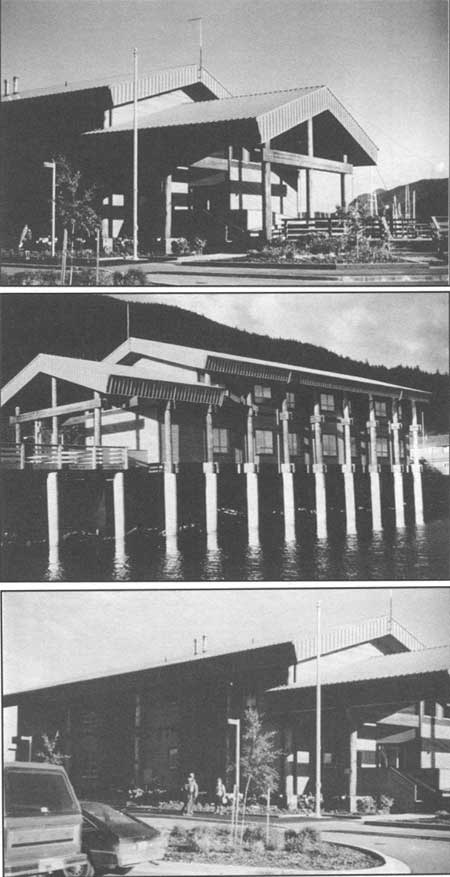

Figure 2-39. Ketchikan Ranger District and Misty Fiords

National Monument Administrative Offices, Ketchikan, Alaska, Region 10

(1986)

|

Gallery of Forest Service

Administrative Buildings

Housing

|

|

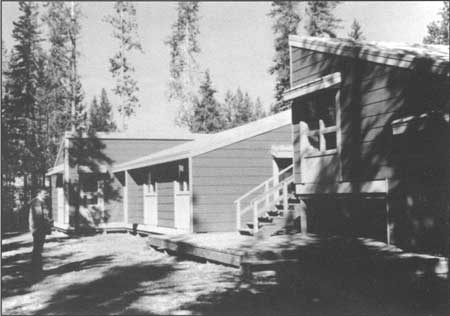

Figure 2-40. Black Rock Crew Quarters, Sequoia National

Forest, Region 5 (1969)

|

|

|

Figure 2-41. Dalton Barracks, Angeles National Forest,

Region 5 (1974)

|

|

|

Figure 2-42. West Yellowstone Barracks, Gallatin National

Forest, Region 1 (1972)

|

|

|

Figure 2-43. Ten-person barracks, Tyrrell Work Center, Bighorn

National Forest, Region 2

|

|

|

Figure 2-44. Philipsburg Ranger Station residence

|

|

|

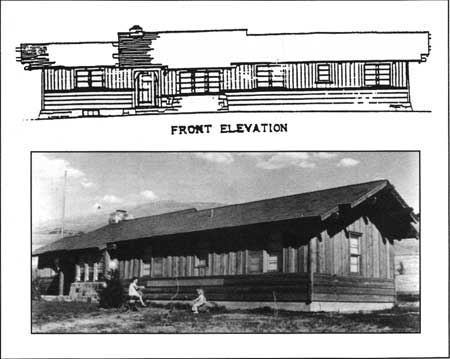

Figure 2-45. Three-room dwelling, Region 4

|

|

|

Figure 2-46. Four-room dwelling, Region 4

|

|

|

Figure 2-47. Residences, Avery Ranger Station, Panhandle

National Forest, Region 1 (1982)

|

|

|

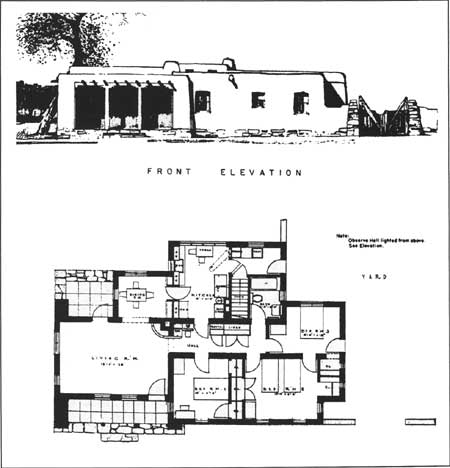

Figure 2-48. Ranger district capitan dwelling, Lincoln National

Forest, Region 3 (1938)

|

|

|

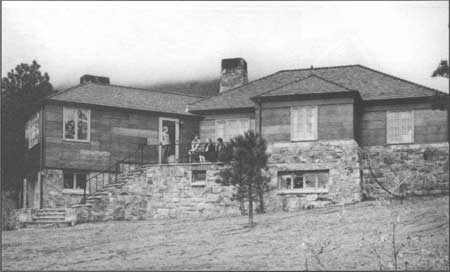

Figure 2-49. Residence, Bailey Ranger Station, Pike National

Forest, Region 2 (1937)

|

|

|

Figure 2-50. Supervisor's residence, Clear Creek Ranger Station,

Arapaho National Forest, Region 2 (1939)

|

|

|

Figure 2-51. Nurseryman's residence, Monument Nursery,

Pike National Forest, Region 2 (1939)

|

|

|

Figure 2-52. Concrete-block residence, Angeles National

Forest, Region 5 (1960)

|

|

|

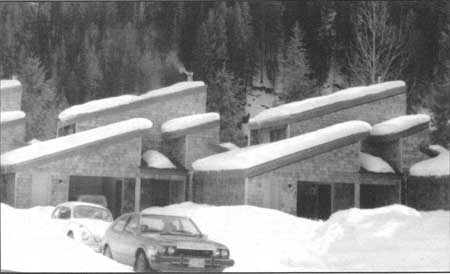

Figure 2-53. Pole building in snow country, Sequoia National

Forest, Region 5 (1970)

|

|

|

Figure 2-54. Dewlling, South Park Ranger District, Pike-San Isabel

National Forest, Region 2 (1975)

|

|

|

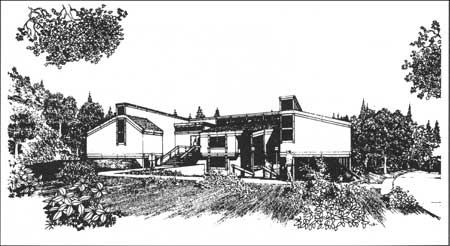

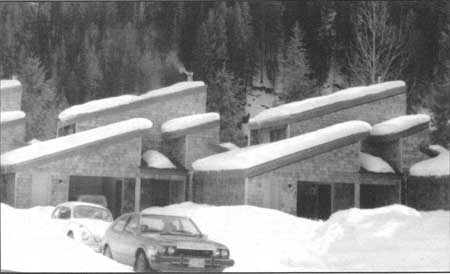

Figure 2-55. Petersburg apartment complex, Tongass-Stikine Area,

Region 10 (1998)

|

Gallery of Forest Service

Administrative Buildings

Warehouse and Storage Facilities

|

|

Figure 2-56. Cochetopa Warehouse, Salida Work Center, San Isabel National

Forest, Region 2 (1938)

|

|

|

Figure 2-57. Warehouse and shop, North Bend Ranger Station, Snoqualmie

National Forest, Region 6 (1937)

|

|

|

Figure 2-58. Shop and barn, Anita Moqui Ranger Station,

Kaibab National Forest, Region 3

|

|

|

Figure 2-59. Big Sur Warehouse, Los Padres National Forest,

Region 5 (1992)

|

|

|

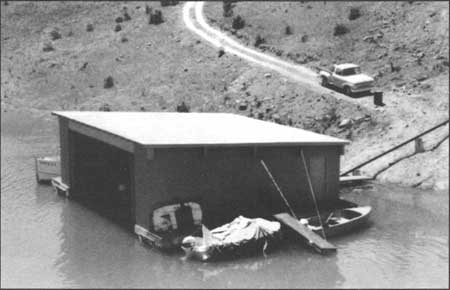

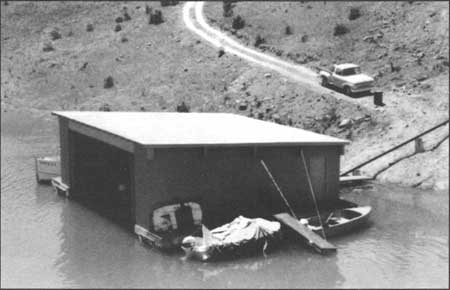

Figure 2-60. Mule Creek Boat Dock and Monorail, Shasta-Trinity

National Forest, Region 5

|

Specialized Fire Suppression Facilities

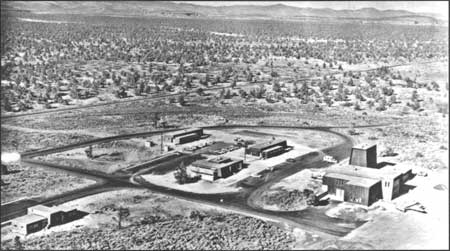

In the late 1950's and early 1960's, a major change came to Forest

Service fire management operations as the airplane became a major player

in fire suppression. Three Regions took the most active role in

providing the new buildings and amenities at airports near small

communities. Region 1 built at Missoula, Montana; Region 5 at Redding,

California, and Region 6 at Redmond, Oregon. Examples of these types of

buildings can be found in Figures 2-61 through 2-63 on pages 92 and

93.

Gallery of Forest Service

Administrative Buildings

Specialized Fire Suppression Facilities

|

|

Figure 2-61. McCall Smokejumper Training Base, Payette

National Forest, Region 4 (1987)

|

|

|

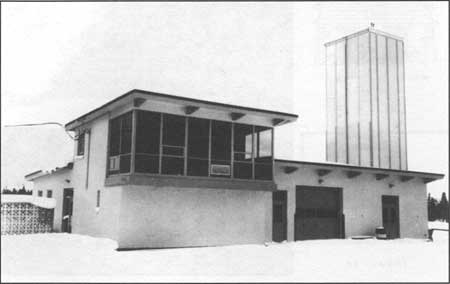

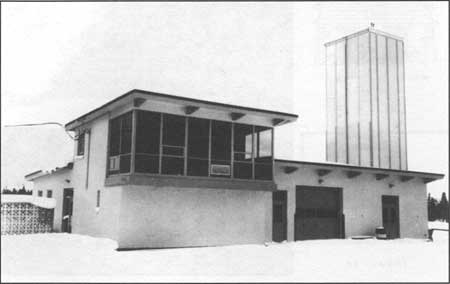

Figure 2-62. West Yellowstone Fire Control Center, Montana,

Region 1 (1965)

|

|

|

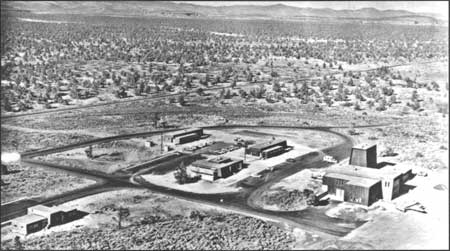

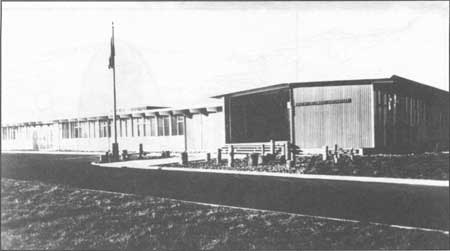

Figure 2-63. Air Center, Redmond, Oregon

|

Lookouts

The Lookout

"Way above the forests, that are in my care.

Watching for the curling smoke—looking everywhere,

Tied onto the world below by a telephone,

High, and sometimes lonesome—living here alone,

Snow peaks on the skyline, woods and rocky ground,

The green of Alpine meadows circle me around,

Waves of mountain ranges like billows of the sea—

Seems like in the whole wide world there's not a soul but me.

Peering thru the drift of smoke, sighting thru the haze.

Blinking at the lightning on the stormy days,

Here to guard the forests from the Red Wolf's tongue

I stay until they take me down, when the fall snows come.

— Robin Adair

California District Newsletter, April 1927 [1]

The detection and control of fires in remote wildlands has posed a

special problem to the Forest Service throughout its history. Federal

Involvement in fire control began with the National Park Service and was

later introduced into the forest reserves. The need for fire detection

and prevention increased as more land was set aside by the Federal

Government and as destructive fires increased.

During the early 1900's, the General Land Office carried out extensive

surveys to properly place monuments to mark forest boundaries. Mapping

was done on each forest, and it was probably during this time that

specific mountaintops were considered for detection locations.

The greatest single motivator for fire protection within the Forest

Service was its Chief, Gifford Pinchot. Part of Pinchot's plan was to

convince the public that the Forest Service mission included fire

detection and prevention. Pinchot and many of his followers believed

that wildland fires should be prevented whenever possible or, if that

failed, that fires be suppressed. Pinchot's vision would shape the

future Forest Service, but lack of funding restricted the development of

fire control until the second and third decades of the 20th

century. [2]

In a paper written in 1910, Henry Graves stated:

The mere fact that a tract is carefully watched makes it safer, because

campers, hunters, and others crossing it are less careless on that

account. By an efficient supervision most of the unnecessary fires can

be prevented, such as those arising from carelessness in clearing land,

leaving campfires, and smoking; from improperly equipped sawmills,

locomotives, donkey engines; etc.

One of the fundamental principles in fire protection is to detect and

attack fires in their incipiency. In an unwatched forest a fire may burn

for a long time and gain great headway before being discovered. In a

forest under proper protection there is some one man or corps of men

responsible for detecting fires and for attacking them before they have

time to do much damage or to develop beyond control.

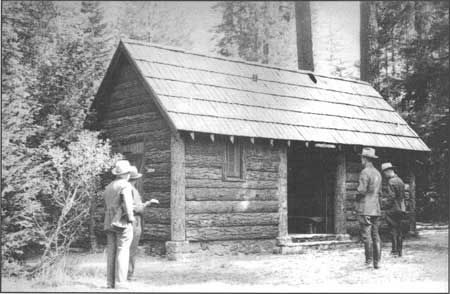

The earliest lookouts were high peaks with an unobstructed view, with

tents as shelters and short mapboard stands for pinpointing the smoke on

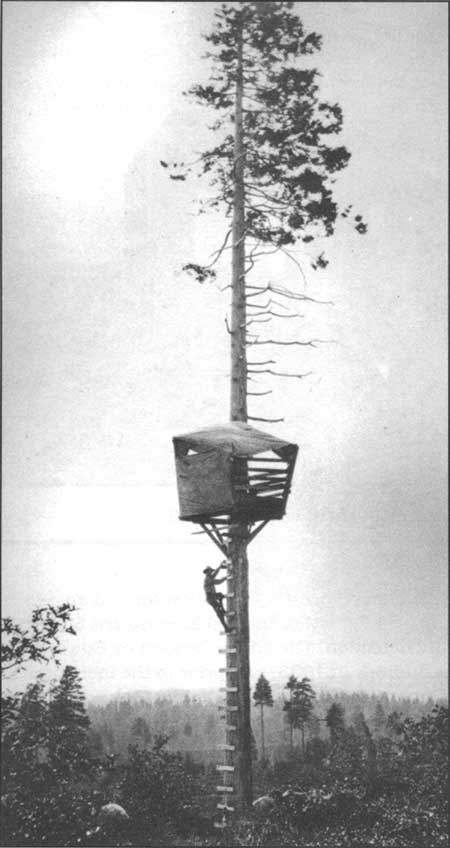

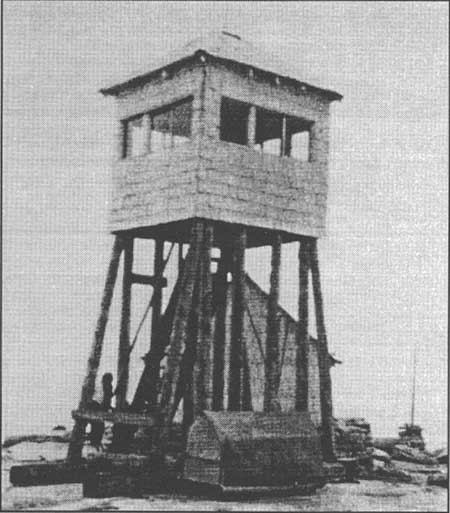

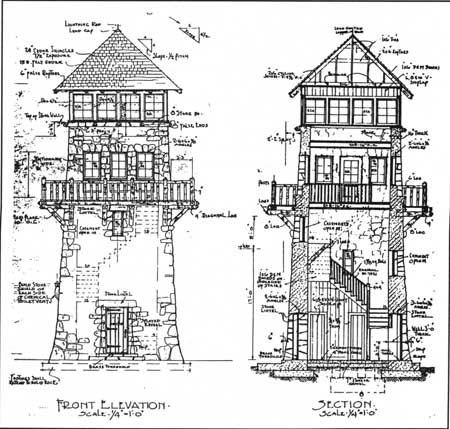

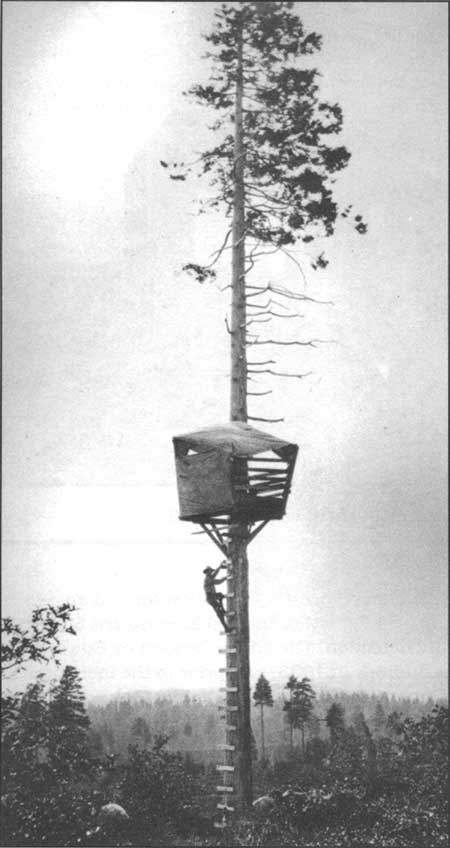

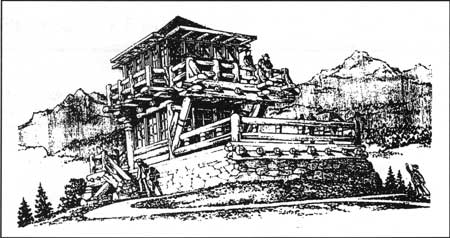

maps. After 1905, tall trees, crude observation-only towers (figure

2-64), platforms, and small log cabins began to be

used. [3]

|

|

Figure 2-64. Lookout tree on Bull Hill, Lassen National Forest,

California (1912)

|

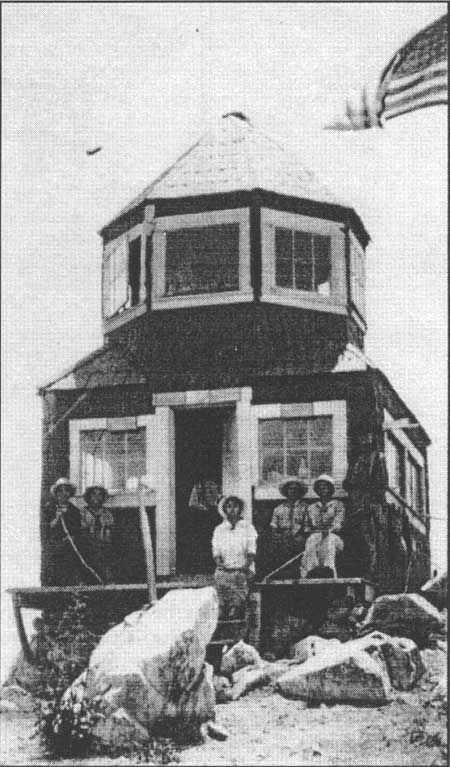

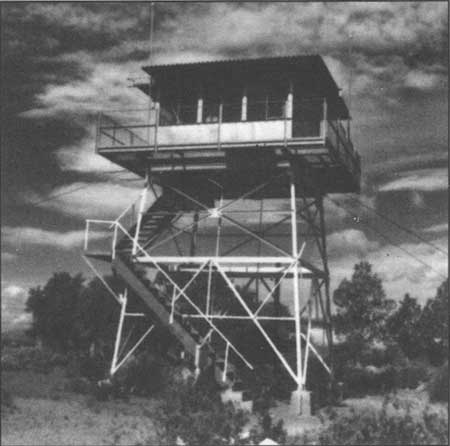

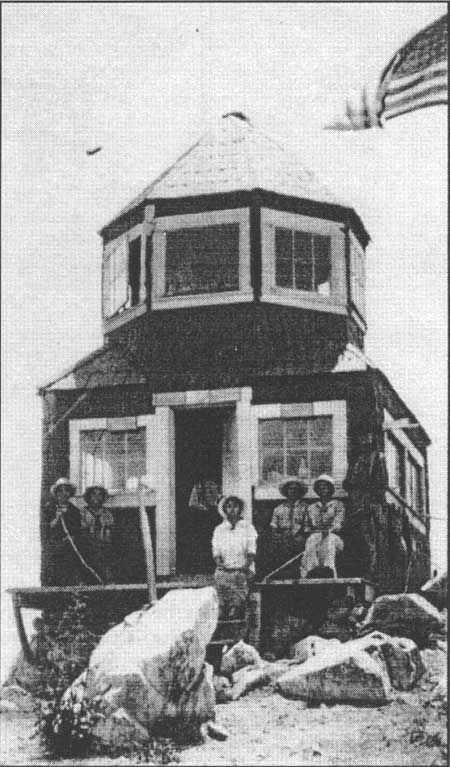

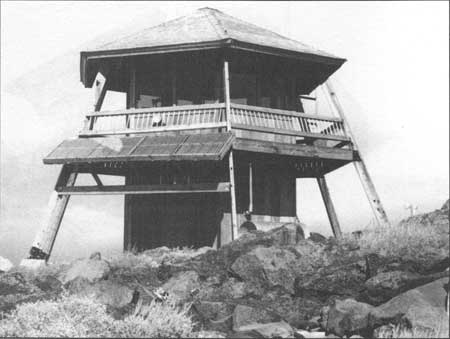

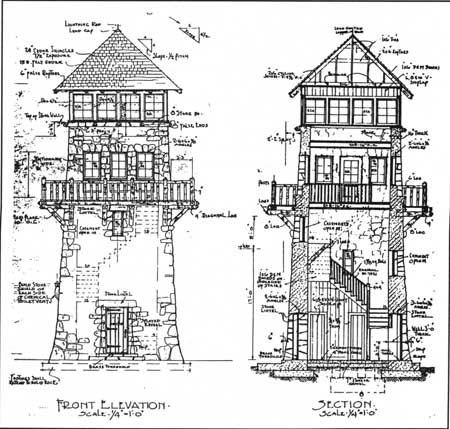

By 1911, cabins and cupolas (figure 2-65) were being constructed on

mountaintops. In 1914, Aeromotor Company observation-only towers with 7-

x 7-foot wood or metal cabs were approved in several Regions. A

commonly built lookout tower design was the timber tower, which was used as

early as 1914. Its design borrowed from similar designs used for years

by the oil industry.

|

|

Figure 2-65. Signal Peak Lookout, Sierra National Forest, Region 5 (1910)

|

In 1914, Coert DuBois in Systematic Fire Protection in the

California Forests wrote:

The lookout man's dwelling, office and workroom should be centered in

one house, on one floor, and in one room. The room can not be less than

12 feet square, and must be so constructed that at any moment of the

day, with the turn of the head, he can see his whole field. He must be

fixed so that while he is cooking, eating, reading, writing, dressing,

washing his clothes, walking about, or sitting down, he can not help but

be in the best position to see. [4]

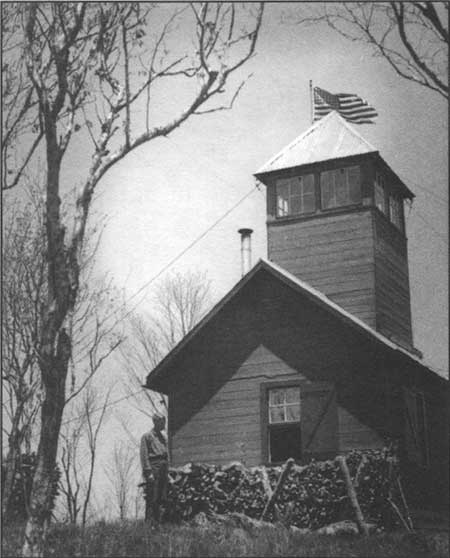

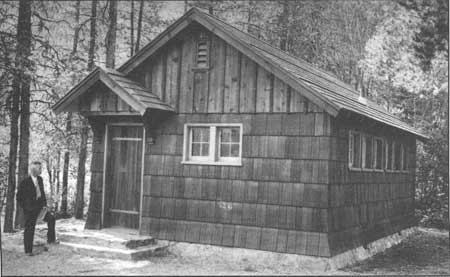

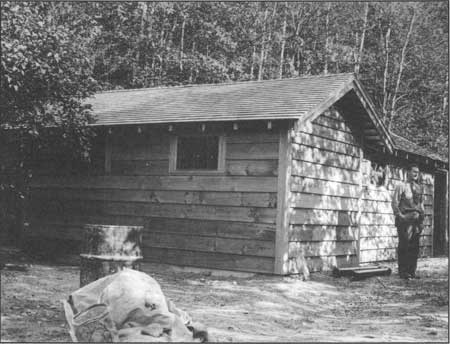

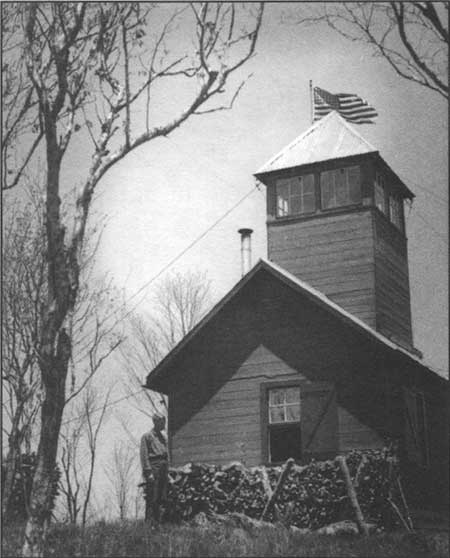

Forests in Region 1 began to experiment with lookout construction as

early as 1915. The first lookout tower in Region 1 was erected in 1916.

It comprised a small cab mounted on a windmill tower. Two of the

earliest lookouts in the Region were built according to the standard

District 6 design. The so-called D-6 lookout was a 12- x 12-foot frame

structure with an observation cupola centrally located on the gable

roof. A third lookout of this vintage was the Cedar Mountain Lookout on

the St. Joe National Forest. This two-story frame structure followed an

improvised plan and is apparently unique. [5]

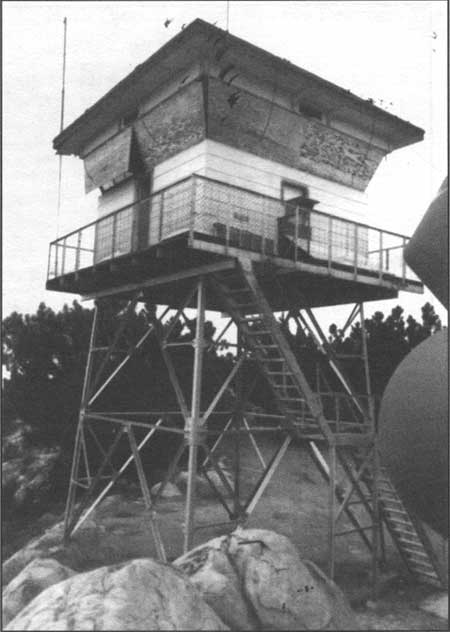

Some lookout points required a tower to obtain a view over the treetops.

This type of structure had to be durable against extreme weather

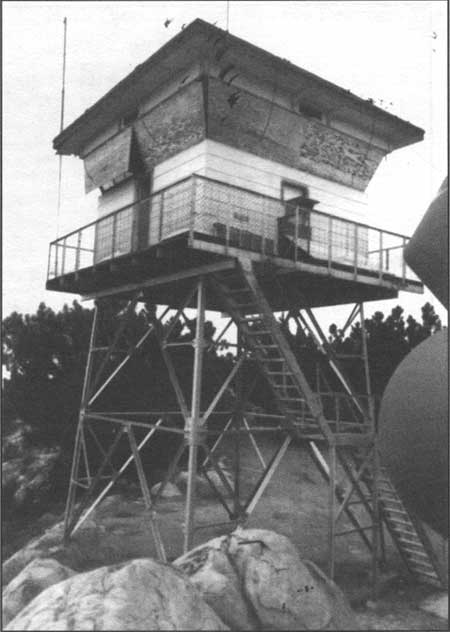

conditions, high winds, and lightning strikes. In the late 1920's, Clyde

Fickes designed a prefabricated lookout cab that was used extensively

throughout Region 1. It was said that the cab did not become rigid until

the windows were installed. [6] Lookout construction in Region 1

received high priority in the 1920's; between 1921 and 1925, 61

structures were completed. Between 1926 and 1930, an additional 130 were

built. By the end of the decade, the total number of occupied points

reached approximately 800. [7]

In the Rocky Mountain Region, despite the acknowledged need for fire

detection facilities, no official funding was allocated for construction

of fire cabins or towers until the early 1910's. As a result, cabins and

towers built during this era were typically constructed by rangers using

scrap materials or materials that could be found on site. Even this,

however, was a step up from the tents that had been previously used to

shelter lookouts. There were few standardized designs in Region 2

through the 1950's. [8]

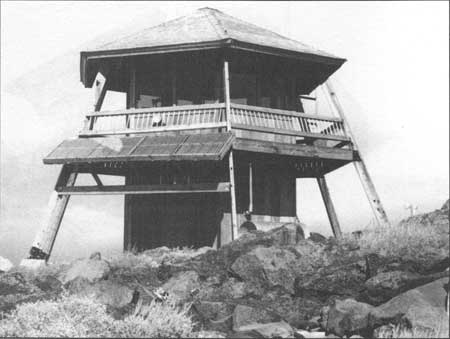

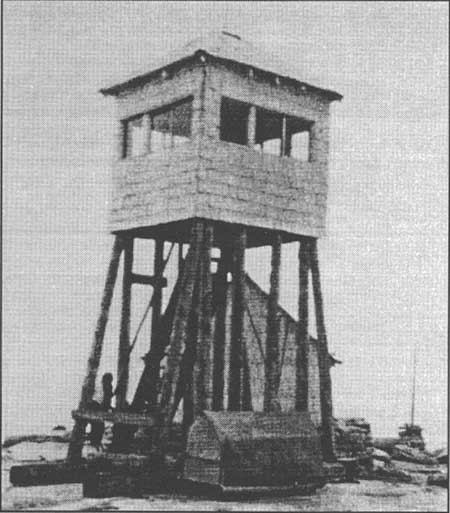

The Leon Peak Lookout on the Grand Mesa National Forest in Region 2

(figure 2-66) is believed to have been constructed in 1911 and 1912 by

Clay Withersteen with the help of Rosco Bloss, a local seasonal Forest

Service employee who was an accomplished carpenter. Bloss was lookout guard in

the summers of 1914 and 1915. All materials were carried up by backpack.

The cupola cabin topology of this lookout consisted principally of a

square log room with a glass observation cupola centered on its

pyramidal roof. [9]

|

|

Figure 2-66. Leon Peak Lookout (photo taken August 1993)

|

In California, the 14- x 14-foot duBois design of 1917 established the

basic floor plan for all live-in cabs built since. The duBois plans

indicate that the cab could be placed on timber towers, but no height

specifications are given. The tower design was of a nonbattered type

similar to railroad water-tank towers. Since then, the live-in

observatory has been the preferred design for California, no doubt a

result of duBois's insistence that the operator should be kept in direct

sight of the seen area at all times; in effect, maximizing the potential

to spot and locate fires—day or night.

In the early 1930's, California Regional Forester S.B. Show formed an

investigative group at the California Forest Range and Experiment

Station to scrutinize every aspect of fire detection. The group, headed

by Edward Kotok, provided a report of its findings in 1933, just prior

to the inception of the Civilian Conservation Corps. The Region

immediately took advantage of the CCC workforce and initiated a massive

program of construction projects, including 250 lookout towers and cabs

built between 1933 and 1942. [10]

The 1937 circular "Planning, Constructing, and Operating

Forest-Fire Lookout system in California" noted:

The lookout house is probably the most distinctive structure used in

forest-fire control. It now represents the product of 20 years of

evolution and reflects many features that have become standard through

long experience by the Forest Service. The details of design vary and

are still in process of change, but the main features now conform

closely to the essentials of a common design [11]

During World War II, the Aircraft Warning Service was established,

operating in 1942 and 1943. Aircraft Warning Service volunteers staffed

selected lookouts 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

After the war, the increase in air pollution limited visibility around

large urban areas. Use of the forests grew, road systems expanded, and

citizen reports of fire began to equal reports by lookouts. Coupled with

the increased aerial surveillance and later satellite surveillance, the

use of the lookout tower correspondingly diminished.

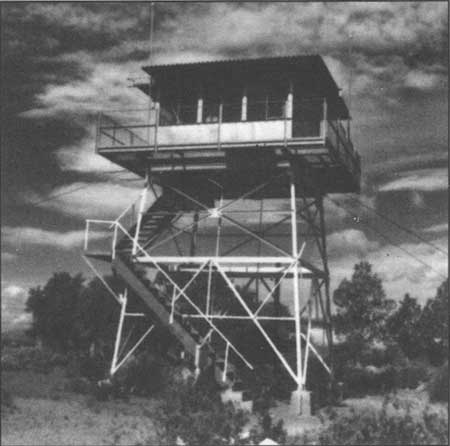

Just after the end of World War II, Keplar Johnson in Region 5 designed

an "experimental lookout" for La Cumbre Peak on the Los Padres National

Forest (figure 2-67). The lookout was innovative, with a steel

frame cab, columns, roof beams, ties, and girders. It also had sloped

windows similar to those on airport control towers. The project was

funded jointly by the Washington Office and Region 5. Compared with

other lookouts, La Cumbre Peak was somewhat expensive, costing $6,500.

With the loss of the CCC and lean budgets after the war, funding for

similar projects was rare.

|

|

Figure 2-67. LaCumbre Peak Lookout, Los Padres National Forest, Region 5 (1945)

|

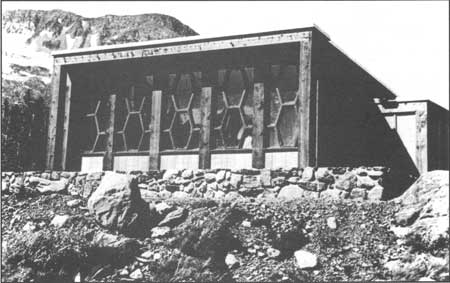

The last new lookout in California was the Antelope Peak Lookout on the

Lassen National Forest (figure 2-68). Built in 1977 with

cooperative funding from NASA, the project tested solar energy

technology. A 1979 Sunset magazine included an article on this

structure: "Sun powers lookout":

"A neat twist to kerosene lamps." That is how one forest ranger

described the new solar system that provides light and power for the

Antelope Peak lookout tower in the Lassen National Forest. The nation's

first to be powered by solar cells has a panoramic view from the top of

timberland and meadows, Mount Shasta, Mount Lassen and cool blue Eagle

Lake. Atop the 7,684-foot peak, the hexagonal tower sits poised like a

rustic spaceship. On its south-facing side are eight panels

that can generate 300 watts at high noon. When sunlight strikes the

silicon wafer cells, they produce enough electricity (stored in 18

batteries) to operate the stations lights, radio, waterpump and

appliances that include a refrigerator and a small television—"all

the comforts of home," as fire lookout Virginia McAllister says.

|

|

Figure 2-68. Antelope Peak Lookout, Plumas National Forest (1974).

This was the last lookout designed in Region 5, a wood tower and cab

built in cooperation with NASA to test solar electric panels. Bob

Sandusky was the designer.

|

The lookouts who spent their time in these remote, isolated forest

environments had to be self-contained people with a sense of humor. A

lookout at the Timber Mountain Lookout on the Colville National Forest

in Region 6, wrote the following poem in 1948:

I like FS biscuits;

think they're mighty fine.

One rolled off the table

and killed a pal of mine.

I like FS coffee;

think it's mighty fine.

Good for cuts and bruises

just like iodine.

I like FS corned beef;

it really is okay.

I fed it to the squirrels;

funerals are today.

Figures 2-69 through 2-74 show additional examples of lookout

design styles in several Regions.

|

|

Figure 2-69. Bald Mountain Lookout. Sierra National Forest, Region 5 (1910)

|

|

|

Figure 2-70. Blue Mountain Lookout, Modoc National Forest, Region 5 (1930)

|

|

|

Figure 2-71. Hayes Lookout, Nantahala National Forest, North

Carolina, a low wooden enclosed structure with a 6- x 6-foot cabin built by the CCC

in 1939.

|

|

|

Figure 2-72. Blue Point Lookout, Cascade Ranger District,

Boise National Forest, Region 4 (1920)

|

|

|

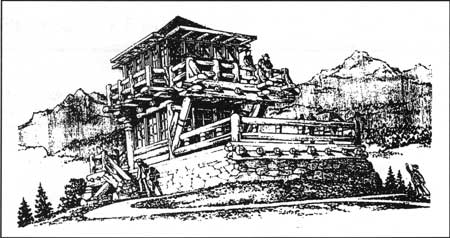

Figure 2-73. Sketch of an early Region 6 lookout.

|

|

|

Figure 2-74. Wayah Bald Observation Tower, North Carolina (1938)

|

Notes

1. Mark Thorton, Fixed Point Fire Detection: The Lookouts, p. 4

2. Ibid., pp. 23-24

3. Ibid., p. 6

4. Ibid., p. 8

5. Historical Research Associates, p. 38.

6. Ibid., p. 8

7. Ibid., p. 38

8. Schneck and Hartley, p. 96

9. Ibid., p. 97

10. Thorton, p. 16

11. Thorton, p. 42

Recreation Buildings

The category of buildings with the second greatest number and diversity

of types is recreation buildings. In a 1940 supplement to the

"Acceptable Plans" book, Groben writes:

All recreation structures should be designed to serve their intended

purpose, be of architectural and engineering soundness, and harmonize

with the forest environment of recreation areas as much as possible,

consistent with utility, good structural design, and reasonable cost of

construction and maintenance.

The very fact that recreation structures should harmonize with the

environment precludes definite standardization of design. Functional

requirements also vary somewhat with locality and are likewise difficult

to standardize in definite pattern. [1]

Foresters became aware of the demand for recreation well before the

creation of the National Park Service in 1916. The 1913 annual report

stated, "Recreation use of the Forest is growing very rapidly,

especially on Forests near cities of considerable size." [2] The

creation of the National Park Service in 1916 touched off an interagency

land struggle that spurred limited Forest Service development of a

variety of recreational sites and buildings, including campgrounds,

trails, shelters, and toilets, as well as encouragement of summer home

sites and structures, throughout the 1920's. Americans visited the

national forests in record numbers, due in part to greater access to

automobiles and the development of roads within the forests. In 1925,

somewhat more than 5 percent of the amount spent on new buildings

supported campground development.

One writer summarized the influence of roads on the growth of

recreational use in the national forests:

Although it was not their original purpose, the 'fire roads' did much to

open the forests to recreational use by hunters and hikers who still

gratefully use them today. The development, especially after World War

II, of four-wheel-drive vehicles such as jeeps made these trails even

more popular. CCC men also built trails for hiking, especially short

ones to spots of particular natural beauty of interest, often providing

bridges and steps for visitors also.

Since road building and automobile ownership were making the forests

accessible for recreation, the Forest Service put some of the CCC boys

to work building campgrounds. A campground might include shelters,

toilet facilities, picnic tables, fireplaces, parking lots, and water

supply systems. . . . Bathhouses were built at some good swimming

areas. [3]

The Forest Service had good reasons for welcoming recreation use of the

forests. One reason was to obtain broad-based political support for the

development of the forests. Public demand for access to the forests

translated into Federal dollars for road construction, which in turn

increased the value of all other natural resources the

forests possessed. Americans were visiting the national forests in

increasing numbers, mainly because automobiles gave them unprecedented

ease of access. But the values that drew them to the forests ran deep.

To the dismay of many, the United States was becoming an urban nation;

the 1920 census revealed that for the first time a majority of U.S.

citizens lived in communities with populations greater than 2,500.

Americans were adjusting rather nervously to a faster pace of life. The

first areas of greatest concentration of summer visitors were on the

Angeles National Forest of southern California, the Mt. Hood National

Forest in northern Oregon, and the Pike and San Isabel National Forests

in central Colorado, all in mountains near cities. [4] Forest

Service management plans for recreation aimed first at preserving

scenery: belts of timber were left uncut along highways, around lakes

and campgrounds, and in settings that were attractive for summer

homes.

Having closed the Columbia River Gorge Park to the development of summer

cabins or private resorts, the Forest Service found itself forced to

assume greater responsibility for the recreational facility development

it had done in other areas of high recreational potential. During the

summer of 1916, the Mt. Hood National Forest developed the Eagle Creek

Campground within the Columbia River Gorge Park. Apparently for the

first time, the Forest Service undertook the construction of a public

campground in the modern sense. Facilities included camp tables, toilets

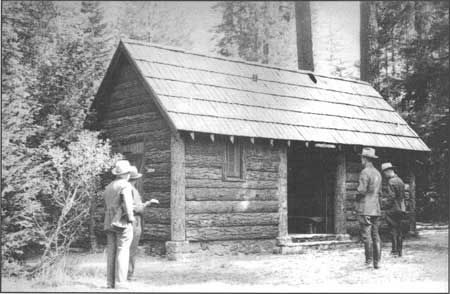

(figure 2-75), a check-in station, and a ranger

station. [5] Ranger Albert Weisendanger and his wife welcomed

many visitors to the campground, which provided a convenient place to

stop along the now historic (but then under construction) Columbia Gorge

Highway.

|

|

Figure 2-75. First substantial toilet building, Mt. Hood National

Forest, Region 6 (1916)

|

Construction of recreational improvements accelerated during the

1930's. CCC enrollees nationwide constructed numerous campground structures.

The next acceleration of recreation development came in 1957 under

the "Operation Outdoors" program, which expanded recreation in the

national forests. Today the national forests are the public's number one

recreational destination point.

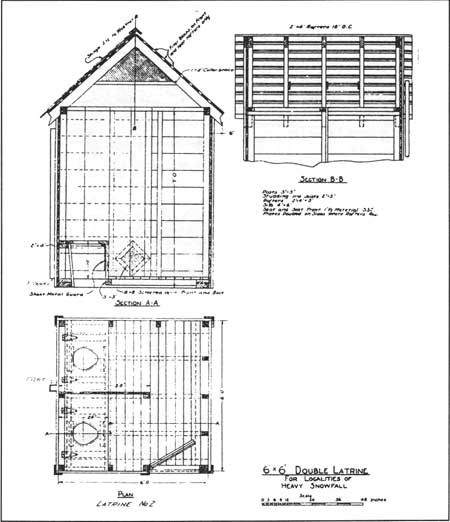

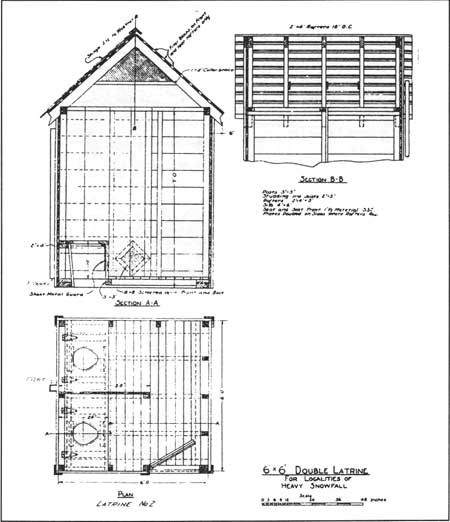

The "Campground Improvement Manual" from Region 5, dated March 1, 1933,

states: "The most important feature on a campground, both from the

viewpoint of the camper and sanitation, is the latrine." [6]

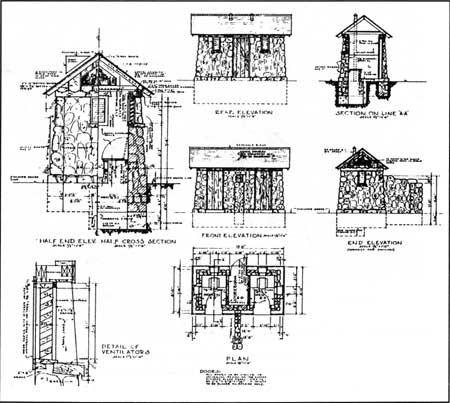

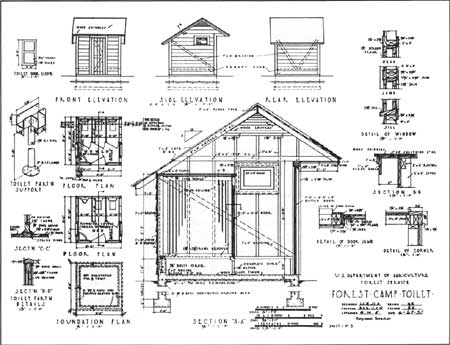

This manual includes six latrine types as regional standards (for

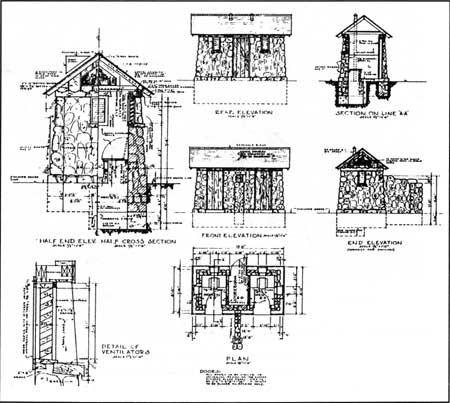

example, figure 2-76 shows the design for localities of heavy

snowfall). These designs were developed over a 10-year period. The

manual includes a bill of materials for all designs. Flush toilets were

rare during this time.

|

|

Figure 2-76. Double latrine design from Region 5

Campground Improvement Manual (1933)

|

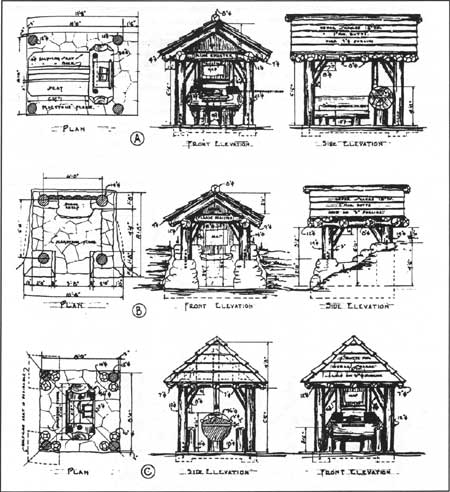

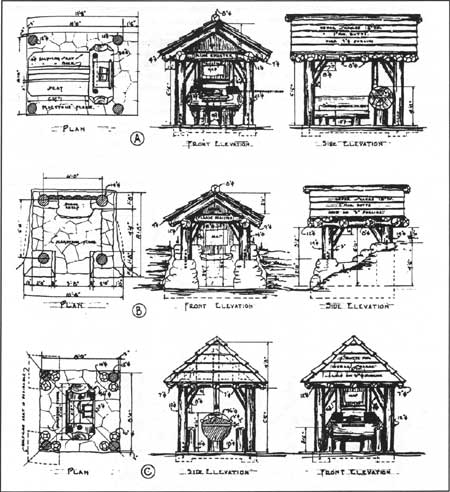

In the Improvements section of the Region 6 Recreation Handbook, dated

February 23, 1935, under Registry Booths, it states: ". . . suggested

types of special registry booths . . . used at class A camps . . . should

be places near natural gathering places." [7] The designs are

quite rustic (figure 2-77).

|

|

Figure 2-77. Design for a registry booth from the Region 6

Recreation Handbook (1935)

|

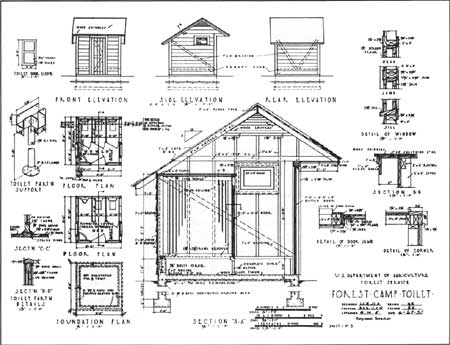

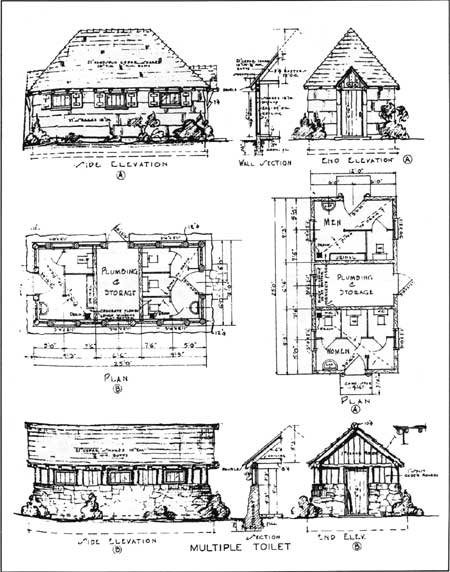

In the Eastern Region's "Handbook of Administration—Recreation,"

dated March 15, 1935, under Forest Camp Facilities, it states: "Comfort

stations will be provided throughout Forest Camps at convenient

locations to accommodate the people in that vicinity. The structures

themselves will be designed to give efficient service for the use and

will be of pleasing proportions and finish" (figure 2-78).

|

|

Figure 2-78. Design for a comfort station from the Eastern

Region's Recreation Handbook (1933)

|

In a foreword to a report in 1936 by consulting landscape architect A.D.

Taylor, Acting Chief of the Forest Service C.M. Granger noted:

. . . that the increasing social use of our National Forests places a

great responsibility on us to preserve the natural aspects of the

forests, and at the same time to provide areas and accompanying

facilities for the many kinds of recreation activities for which so many

millions of people enter the National Forests each year. [8]

In the 1960's, Congress passed a bill funding construction of

campgrounds at new and existing reservoirs and lakes in the Nation;

these had a considerable impact on the Forest Service recreation design

and construction program. This increased funding started a trend toward

campgrounds with larger capacity in the more urban forests.

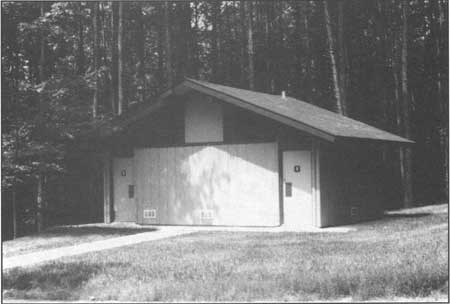

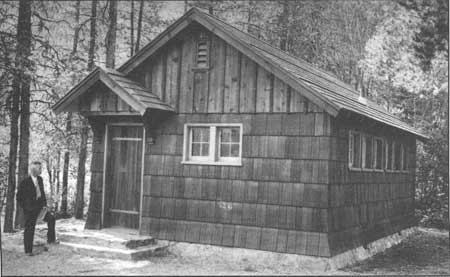

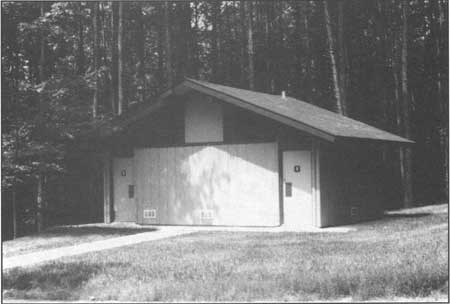

Almost all Regions publish a catalog of standard recreation structures

that is edited at least every 5 years. The most prevalent single type of

building for the recreation public is the toilet structure. These range

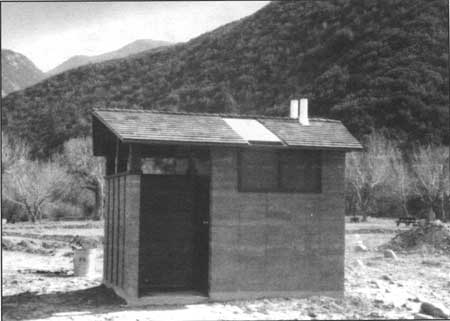

from screened backcountry (wilderness) toilets to one-hole pit toilets

for remote campgrounds to the flush comfort station for urban-type campgrounds. Because

most new architects start out with a toilet design or redesign, there

are as many different designs as there are designers. See figures

2-79 through 2-92 for additional examples of toilet buildings,

including modern vault and flush toilets.

|

|

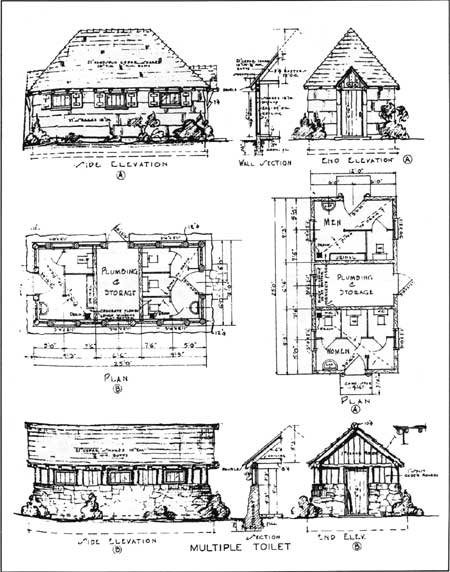

Figure 2-79. Comfort station with separate multiple toilets, Region 6 (1936)

|

Toilet Buildings of the 1930's

|

|

Figure 2-80. Combination toilet and registration building, Rogue River

National Forest, Region 6 (1936)

|

|

|

Figure 2-81. Toilet building and bathhouse, Kaniksu National

Forest, Region 1 (1936)

|

|

|

Figure 2-82. Toilet building, White Mountain National Forest,

Region 7 (1936)

|

|

|

Figure 2-83. Toilet building, Chelan National Forest, Region 6 (1936)

|

|

|

Figure 2-84. Seedhouse Campground toilet, Routt National Forest,

REgion 2 (1935)

|

|

|

Figure 2-85. Region 4 standard two-unit comfort station (1934)

|

Modern Vault Toilets—Designs of the 1960's

|

|

Figure 2-86. Two-hole vault, southern California, Region 5

|

|

|

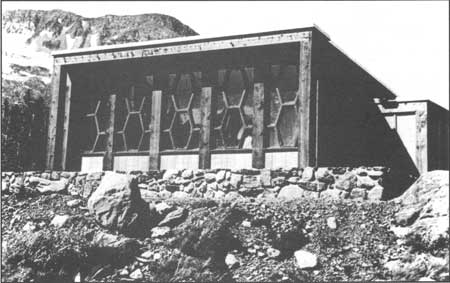

Figure 2-87. Mountaintop vault structure, Region 5

|

Flush Toilets

|

|

Figure 2-88. Flush toilet, San Bernardino National Forest, Region

5 (1960)

|

|

|

Figure 2-89. Flush toilet, Plumas National Forest, Region 5 (1960)

|

|

|

Figure 2-90. Combination flush toilet, Region 6

|

|

|

Figure 2-91. Modern flush toilet, Region 8 (1980)

|

|

|

Figure 2-92. Portage Glacier restroom, Chugach National Forest,

Region 10 (1962)

|

A continuing concern with vault and pit toilet buildings was, and still

is, the venting of the holding tank for the human waste. Odor and

insects have made these structures less attractive to the national

forest recreational visitor. Over the years, the designs of toilet

buildings with holding tanks or pits have employed any number of

inventive solutions; these have included fans, solar heaters, wind

diverters, and other devices to increase the flow of air upward out of

the vault to decrease odors in the building. Briar Cook, a research

engineer at the Forest Service's San Dimas Equipment Development Center

in California, spent the last years of his career attempting to devise a

"sweet smelling toilet." One year he spent many hours down in the tanks

doing an inventory of all items deposited there (his list was several

pages long). His final "gift" to the agency was a series of toilet

buildings with technical innovations to properly vent the vaults to keep

unwanted odors and insects out of the interiors of these buildings.

These were shown to perform well in laboratory tests, but if the

buildings were constructed in the wrong location or orientation in the

field, the venting did not work.

Looking at the styles of the various recreation structures of the Forest

Service shows that the predominate character of these buildings in the

rural areas is rustic—labor intensive with logs, wood shakes or

shingles, rough planks, and stone. In urban areas, the buildings are

more finished, with plywood siding or concrete blocks and flat roofs,

and are more visible to the public. The variety of building types and

design styles can be seen in figures 2-93 through 2-102 on

pages 119 to 124.

Special Structures

|

|

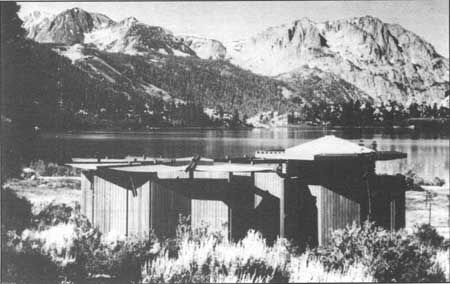

Figure 2-93. Mono Hot Springs bathhouse, Sierra National

Forest, Region 5 (1963)

|

|

|

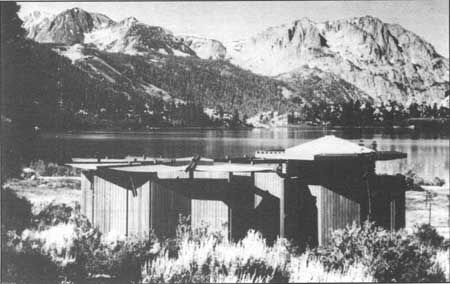

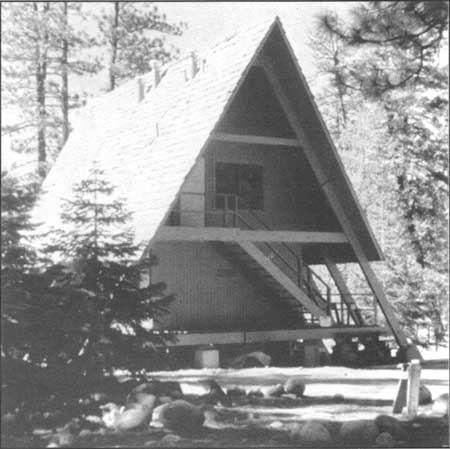

Figure 2-94. Change pavilion, June Lake, Inyo National

Forest, Region 5 (1964)

|

|

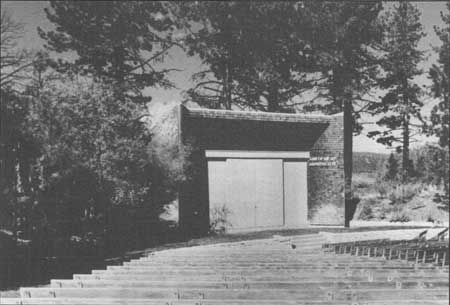

|

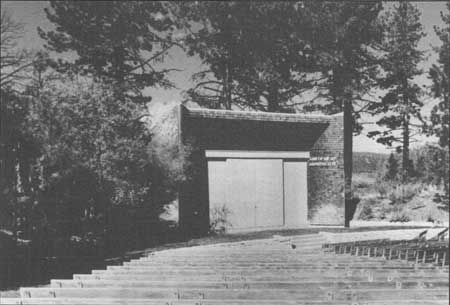

Figure 2-95. Amphitheater with rear-projection building,

Lake Tahoe Visitor Center, Region 5 (1964)

|

|

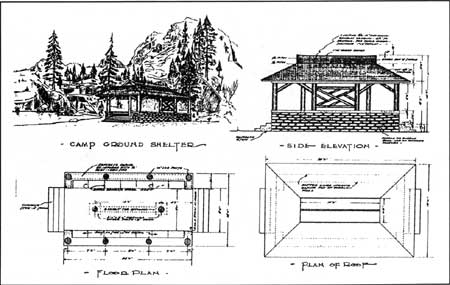

|

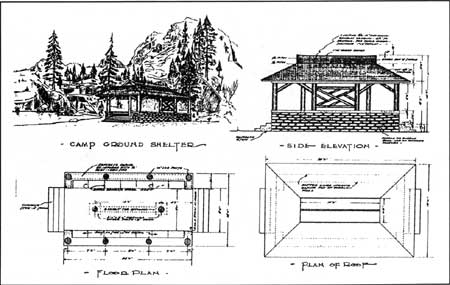

Figure 2-96. Standard Region 4 campground shelter (1934)

|

|

|

Figure 2-97. Picnic shelter, Cibola National Forest, Region 3 (1936)

|

|

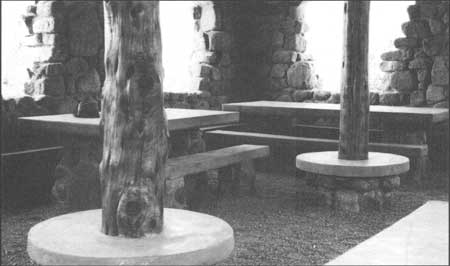

|

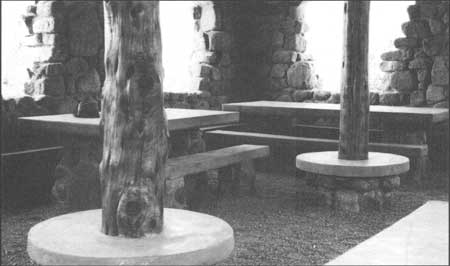

Figure 2-98. Interior detail of picnic shelter, Cibola

National Forest, Region 3 (1936)

|

|

|

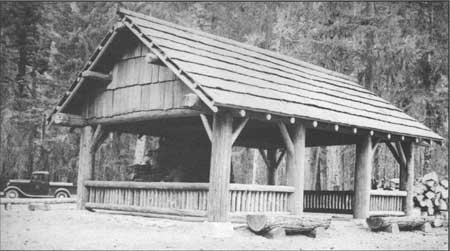

Figure 2-99. Picnic shelter, Snoqualmie National Forest, Region

6 (1936)

|

|

|

Figure 2-100. Picnic shelter, Longdale Recreation Area, George

Washington National Forest, Region 8

|

|

|

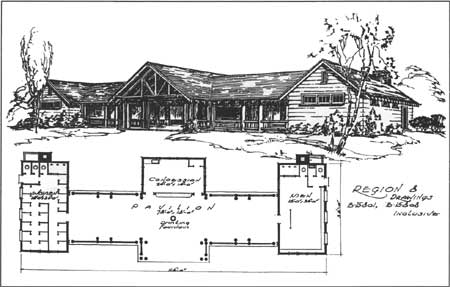

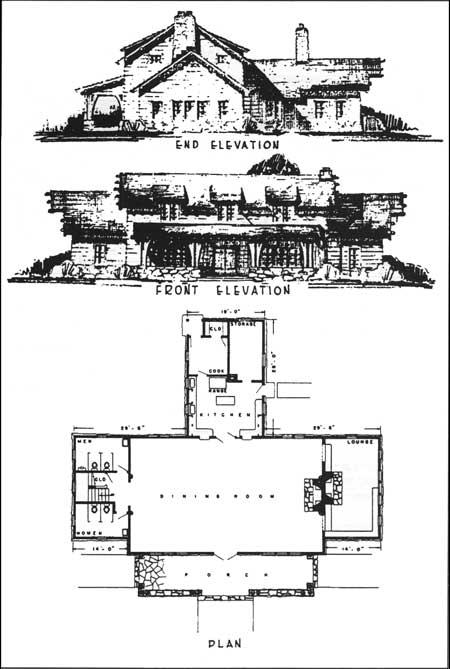

Figure 2-101. Messhall, Organization Camp, Wyoming National Forest, Region 4

|

|

|

Figure 2-102. Bath house and pavilion, Region 8

|

In the early 1990's, recreation became the number one use of the

national forests as well as the greatest money maker for the U.S.

Treasury from receipts. Since the mid 1990's, more and more programs

have focused on the recreational needs within the national forests,

including refurbishing, rebuilding, and adding to the recreational

structures.

Notes

1. USDA Forest Service, "Recreation

Structures," Acceptable Plans, p. 2.

2. USDA Forest Service, "A History of

Outdoor Recreation Development in National Forests, 1891-1942," p.

2.

3. USDA Forest Service, Mountains

and Rangers: A History of Federal Forest Management in the Southern

Appalachians, 1900-91, p. 78.

4. USDA Forest Service, "A History of

Outdoor Recreation," p. 3.

5. Ibid., p. 4.

6. USDA Forest Service, Campground

Improvement Manual, p. 9.

7. USDA Forest Service, Recreation

Plans—North Pacific Region.

8. Taylor, Problems in Landscape

Architecture in the National Forests, Foreword.

Timberline Lodge: A Legacy from the WPA

Hundreds of thousands of visitors come to Timberline Lodge each year,

making it one of the top two tourist attractions in the State of Oregon.

Timberline Lodge stands just above the timberline on the south side of

Mount Hood in the Oregon Cascade Range. A majestic structure in wood and

stone, it was built mostly by Works Progress Administration (WPA) labor

between 1936 and 1938. The lodge is traditional in style and has

similarities with wilderness hotels, but it is unique to the Forest

Service because it was designed by agency architects. It is one of only

two national historic landmark properties in the National Forest System.

The other is Grey Towers in Milford, Pennsylvania—Gifford Pinchot's

ancestral home.

A project application form for a WPA grant for the Timberline project, a

year round recreation center on Mount Hood, was sent to Washington on

September 7, 1935. The initial role of the Forest Service in the

Timberline project was that of sponsor, but in a limited capacity. The

project was guided by the Mount Hood Recreational Association, an

unincorporated group of Portland citizens who were interested in the

development of recreational housing facilities at Timberline on the

slopes of Mount Hood. While stating that the Forest Service would

supervise the development, the Mount Hood Recreational Association

clearly planned to exercise control over the architecture of the

hotel.

|

|

Figure 2-103. Rendering of proposed Timberline Lodge by Linn Forrest (1935)

|

There was no money available to pay for the 6 percent fee a private

architectural firm would charge for the design of the hotel. Forest

Service Headquarters recommended that Gilbert Stanley Underwood be

consulting architect and that the design be done by a team of Forest Service

architects headed by Tim Turner from the Region 6 office. Underwood was

noted for his design of the Ahwanee Hotel in California's Yosemite

National Park and a lodge at Zion National Park and for his work with

the Union Pacific Railroad, including stations in Omaha and Kansas

City. His name appears on some sketches of elevations for Timberline

Lodge, but not on any of the construction drawings.

|

|

Figure 2-104. Tim Turner (center front) poses with Timberline Lodge

workers in 1937

|

The team of Forest Service architects for the Timberline Lodge included

Turner (as leader), Linn Forrest (lead designer for the lodge), Gif

Gifford, and Dean Wright. These were all men who had grown up in the

Northwest and who brought many years of experience with all facets of

architecture, including hotel design, to their positions in the Forest

Service. They were men who were familiar with historic architecture and

yet kept abreast of current developments on both the national and

international levels.

Turner led this team to produce a unique design and details for the only

major recreation development on Forest Service land by the WPA. Turner

was given the task to provide Forest Service inspection of the

construction of the lodge.

The design of the lodge was called "Cascadian" and was thought of as an

American version of European Alpine architecture. E.J. Griffith, in an

interview in 1976, said:

"America has never developed any highland architecture as the Alpine of

Europe. So an attempt was made to establish a distinctive style, which

subsequently was given the name of Cascadian architecture. With steep

sloping roofs, massive and rugged walls to meet the weight of the snows

and force of winds, the design was the development of a pioneer motif .

. ."

The strength of the design of Timberline Lodge is in the head house and

its long, sloping roof (figure 2-105). It is a unique and powerful

structure.

|

|

Figure 2-105. Exterior view of Timberline Lodge. PHOTO BY LAWRENCE HUDETZ

|

Nonetheless, for the time when it was built, the lodge was

traditional rather than innovative in style. The architects of

Timberline Lodge were less influenced by the "modern movements" from the

Bauhaus or Art Deco than by European chateau and alpine architecture.

These traditional styles were the antecedents of Timberline

Lodge. [1]

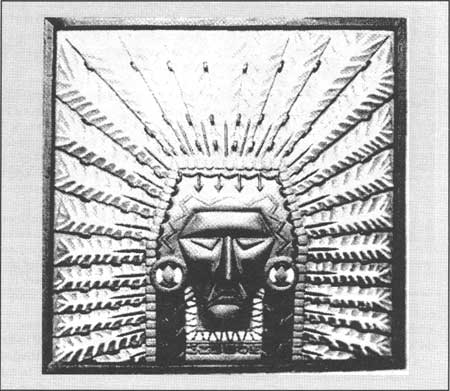

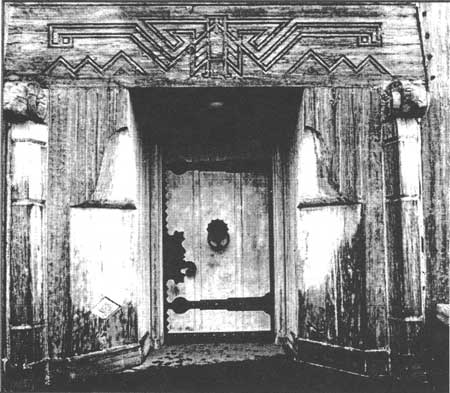

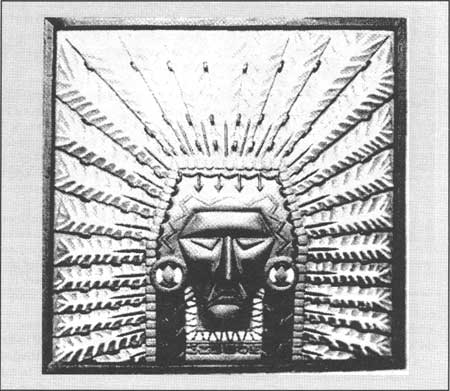

Forrest designed the carved panel of an American Indian chief wearing a

headdress on one of the entrance doors (figure 2-106). The beadwork

at the bottom of the panel between the braids is made up of the initials

of the Forest Service architects, the Regional Engineer, and their

secretary: JF (James Frankland, Regional Engineer), WIT (Tim Turner,

supervising architect) HG (Gif Gifford, architect), DW (Dean Wright,

architect), EDC (Ethel Chaterfield, secretary), and LF (Linn Forrest,

architect). [2]

|

|

Figure 2-106. Carved panel detail from Timberline Lodge door. PHOTO BY LAWRENCE HUDETZ

|

Construction began on June 13, 1936, even though the plans were not

actually approved until July. Ward Gano, a recent engineering graduate

from the University of Washington, was assigned by the Forest Service to

be the resident engineer inspector. The weather was a primary

consideration in this construction project. It was necessary to frame

the building during the summer of 1936. Fortunately, the first snows did

not start until December that year. [3]

The lodge was formally dedicated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

on September 28, 1937. The President called the lodge "a monument to

the skill and faithful performance of workers on the rolls of the Works

Progress Administration."

As the Timberline project neared completion in 1938, the Forest Service

called for bids from hotel companies interested in operating it. Very

few bids materialized, and the Mt. Hood Development Association appealed

to Portland businessmen to form an operating company. The lodge was not

opened to the public until February 4, 1938.

The architects of Timberline Lodge felt that the lodge was designed both

for people who could afford to stay in the individual guest rooms and

also for younger, generally less wealthy skiers, who would stay in the

dormitory. The architects did not anticipate the heavy use of the lodge

by summer visitors, nor could they predict the future boom of skiing

as a popular sport.

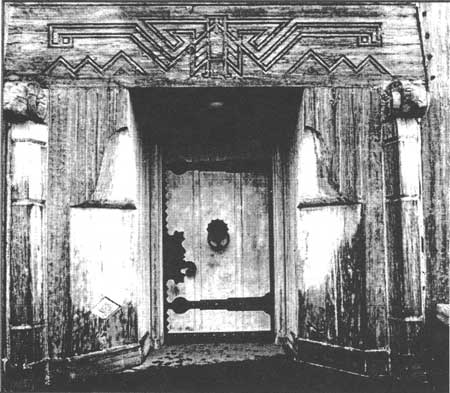

|

|

Figure 2-107. Doorway, Timberline Lodge

|

Notes

1. Griffin and Munro, p. 5.

2. Ibid., p. 79.

3. Ibid., pp. 6-7.

Visitor Centers

Recreation in the national forests has been seen as one of the primary

multiple-use categories since the concept was first articulated by

Gifford Pinchot in the early 1900's. Camping, hiking, hunting, and other

outdoor recreational activities have taken place on national forests

since they were formed.

Although the Park Service developed and implemented the concept of

visitor information centers early in its history, the concept is still

fairly new to the Forest Service. Most visitor contact points have been,

and still are, made in the ranger district headquarters, where the

public receives maps and directions from the clerk in the reception

area. However, facilities designed to offer visitor information services

are a way to help the public not only to enjoy the national forests but

to understand the nature of the resources and their management.

For the design architects, visitor center buildings became a vehicle for

their most creative expressions. Many of these structures were designed

by Forest Service architects. Even when the designs were given to

private architectural firms, the prospectuses and preliminary plans and

styles were dictated by Forest Service architectural staffs. The styles

of the buildings reflected more contemporary architectural elements

than most of the other building types. The structures were built in

areas of the national forests that were unique in their settings and

that attracted a large number of visitors.

Just as the toilet building was the "bane" of the designer, the visitor

center was the "joy." The high point in many a Forest Service

architect's career was the assignment to participate in the development,

design, and production of plans for new visitor centers. The buildings

produced both by Forest Service architects and private firms are a

positive reflection on the agency.

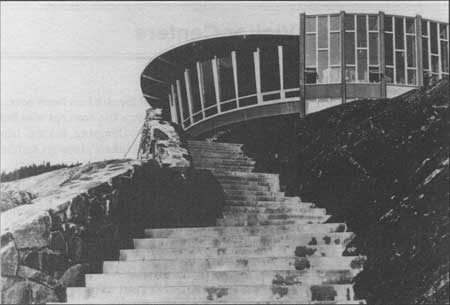

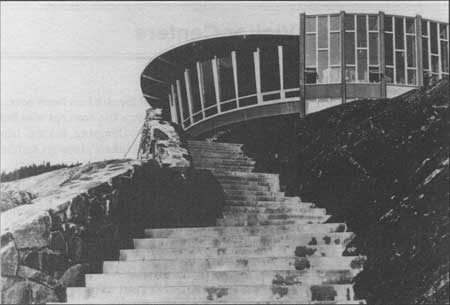

The first building designed and constructed as a visitor information

center was the Mendenhall Glacier Visitor Center, built in 1961 near

Juneau, Alaska. Conceptual ideas and sketch plans were developed by the

Regional Office recreation staff. The proposal and plan for the

observatory arose from a need for a comfort station (public toilet

facility) at this already popular attraction, which for public

convenience included a trail, viewing area, and sign. Linn Forrest

Architects of Anchorage, Alaska, was contracted to prepare the

construction documents. Forrest was one of the architects on the

Timberline Lodge design team during the 1930's. The simple needs of the

first concepts grew to include an observatory with a coffee shop, concessionaire

apartment, office, and storage space (figure 2-108).

|

|

Figure 2-108. The first Forest Service visitor center at Mendenhall

Glacier Juneau, Alaska (1961)

|

In 1991, it was time to bring the building up to the present needs and

codes (especially the Americans with Disabilities Act). During the

years 1995, 1996, and 1997, funding was provided to make the changes

designed by a private architectural firm out of Seattle, Washington.

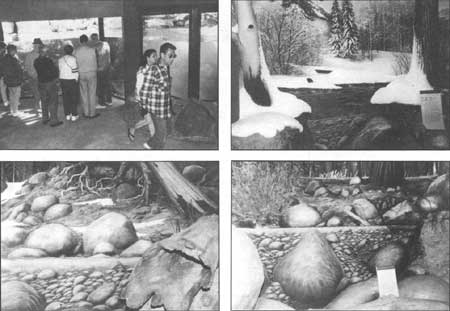

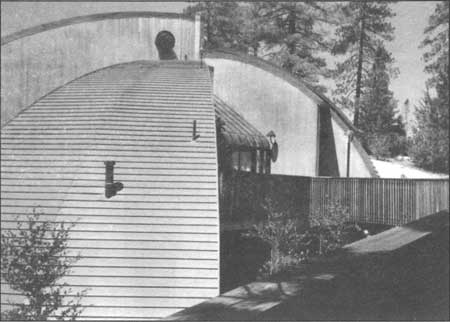

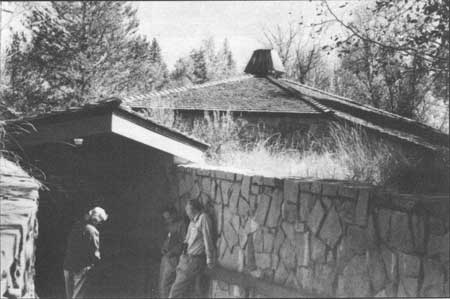

An unusual and challenging example of this building type was the Stream

Profile Chamber at South Lake Tahoe, California (figures 2-109 and

2-110). The architectural design prospectus was completed in September

1964. Richard Modee, a new architect on the Regional Office engineering

staff, was assigned the design of the building and John Grosvenor was

assigned as the liaison between the forest and the Regional Office.

Modee was a graduate student in landscape architecture at the University

of California at Berkeley; he had a B.A. in architecture from the Rhode

Island School of Design.

|

|

Figure 2-109. Stream Profile Chamber, South Lake Tahoe,

California, Region 5

|

|

|

Figure 2-110. Stream Profile Chamber, entrance detail

|

Grosvenor and Modee went up to the proposed building site before the

winter snows began in 1964. The forest had done the surveying and had

staked an approximate location on the ground. The two architects also

met with Bob Morris to discuss the exhibits and how they would affect

the flow of people in the structure. Modee had a rough sketch of the

building showing the viewing windows and the entrance and exit ramps.

Morris had some good suggestions regarding the shape and layout of the

interior space. At the end of the meeting, the three felt they had a

good understanding of the project and proposed to meet again just after

the first of the year.

There were some difficult structural engineering issues. First was how

to keep the structure from floating in the winter, when the water level

in the meadow was close to the surface. Second was how to keep the

moisture out of the underground chamber, both intrusion from underneath

and water flowing down the two ramps. Third was how to span the large

room with a sloping roof.

The architectural engineering firm selected was

Pregnoff and Mathhis of San Francisco, with Ken Mathhis as structural

designer. Mathhis had worked for the Forest Service in bridge design before

going into private practice.

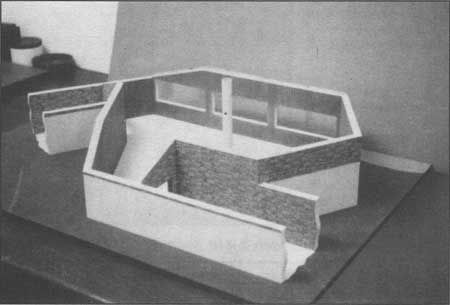

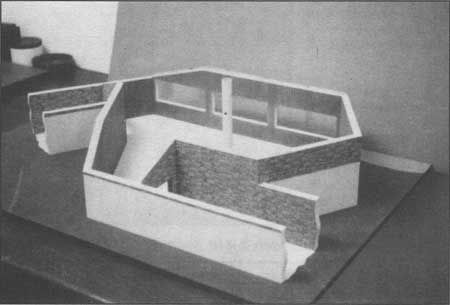

Modee finished the preliminary design sketches and

made a 1/2-inch-scale model (figure 2-111), and Grosvenor

prepared a preliminary cost estimate. In the spring of 1965, Modee,

Grosvenor, and Morris, made a presentation to Forest Supervisor Doug

Leisz and Forest Recreation Officer Ellis Smart. The preliminary

estimate for the building alone was $45,000. Over and

above this would be the trail to the building, the

stream diversion and pool, and the exhibits. Morris had completed the

exhibit prospectus, focusing on public education regarding stream

pollution, life and history of the Kokanee salmon, and resource

management of the Lake Tahoe watershed, including Taylor Creek, the

location of the Stream Chamber.

|

|

Figure 2-111. Scale model of Stream Profile Chamber

|

Leisz and Smart were pleased with what had been developed up to this

point. They made some suggestions to the design team and agreed to

prepare a budget request to the Chief for fiscal year 1966 funding, hoping

for a start of construction in spring 1967. Smart was given the task of

preparing the total estimate and writing up the request for the

structure.

Assuming there would be no problems in getting the funds, Modee started

the final design soon after returning from the meeting. He had a

predesign meeting with Mathhis to go over the structural concerns. The

Eldorado engineering surveyors started right away doing the site survey,

including the water table depth.

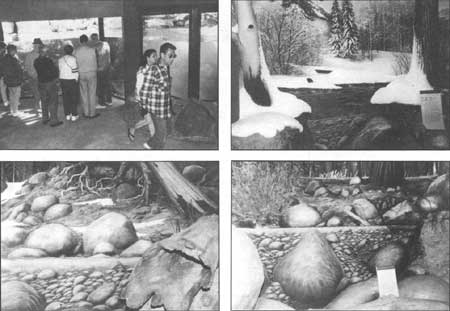

Completed in 1967, for 30 years this building has drawn thousands of

visitors each summer to look through the 30 feet of viewing windows and

see fish swimming in the manmade pool (figure 2-112). In October

1997, a rededication of the building was held after a major remodeling

of the interior (costing $640,000—half of which came from private

donors). The windows had been greatly modified to articulate into the

building and into the pool; one of the ramps had been modified to meet

the latest accessibility standards; and the interior exhibits had been

modernized. More than 3,000 people came the first day to see the changes

(the building had been closed for 2 years).

|

|

Figure 2-112. Interior views of remodeled Stream Profile Chamber

|

Figures 2-113 through 2-138 on pages 137 through 151 show the

range of architectural styles used for the Forest Service visitor

centers throughout the Nation over the years. Table 1 contains a list of

the Forest Service visitor centers.

Table 2-1. National Forest Visitor Centers

| Region/Forest | Name | Built |

|

| 1—Gallatin | Quake Lake | 1966 |

| 1—Clearwater | Lolo Pass |

|

| 1—Flathead | Hungry Horse |

|

| 2-Arapaho/Roosevelt | Idaho Springs | 1964 |

| 2-Black Hills | Pactola | 1969 |

| 2-Nebraska | National Grasslands | 1991 |

| 2-Bighorn | Burgess Junction | 1992 |

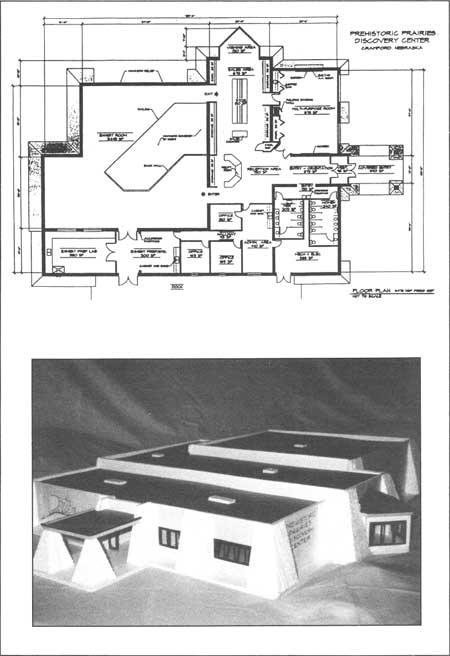

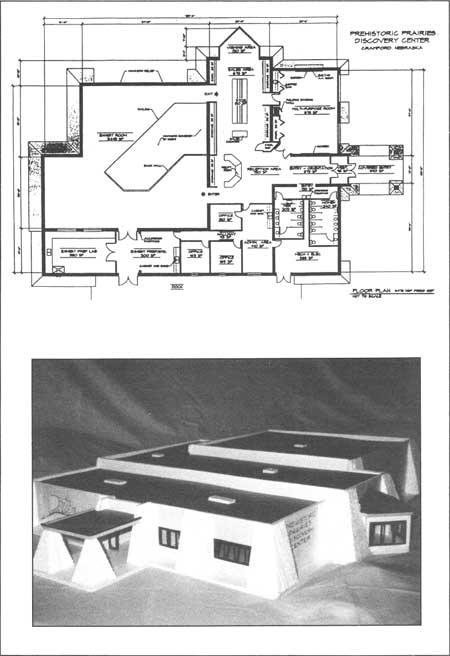

| 2-Nebraska | Prehistoric Prairies | Proposed |

| 3-Coronado | Sabino Canyon | 1963 |

| 3-Gila | Gila Cliff Dwellings | 1967 |

| 3-Apache-Sitgreaves | Big Lake | 1967 |

| 3-Carson | Ghost Ranch | 1970 |

| 3-Coronado | Palisades | 1970 |

| 3-Kaibab | No. Kaibab | 1991 |

| 3-Coronado | Columbine | 1992 |

| 3-Coronado | Portal | 1993 |

| 3-Apache-Sitgreaves | Mogollon | 1993 |

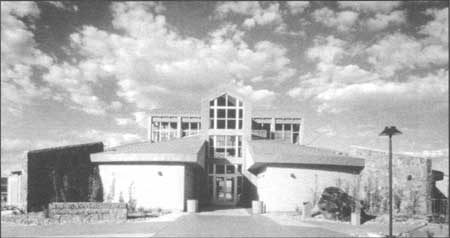

| 3-Tonto | Roosevelt Lake | 1994 |

| 3-Kaibab | Williams Depot | 1994 |

| 3-Lincoln | Sun Spot Solar Observatory | 1997 |

| 4—Sawtooth | Red Fish Lake | 1963 |

| 4—Ashley | Flaming Gorge | 1965 |

| 4—Ashley | Red Canyon | 1966 |

| 4—Sawtooth | Sawtooth NRA | 1977 |

| 4—Uinta | Strawberry | 1983 |

| 4—Briger-Teton | Briger-Teton | 1991 |

| 5—Eldorado | Lake Tahoe | 1964 |

| 5—Shasta-Trinity | Trinity Lake (destroyed by fire) | 1964 |

| 5—Eldorado | Stream Profile Chamber | 1967 |

| 5—Inyo | Mammoth Lakes | 1967 |

| 5—Angeles | Chilao | 1980 |

| 5—Inyo | Mono Lake | 1990 |

| 5—Angeles | Grassy Hollow | 1996 |

| 5—Inyo | Shulman Grove | 1997 |

| 5—San Bernardino | Big Bear | 1997 |

| 5—Sequoia | Lake Isabella | 1997 |

| 6—Siuslaw | Cape Perpetua | 1967 |

| 6—Deschutes | Lava Lands | 1975 |

| 6—Gifford Pinchot | Mount St. Helens (Silver Lake) | 1986 |

| 6—Gifford Pinchot | Mount St. Helens (Coldwater) | 1993 |

| 6—Gifford Pinchot | Mount St. Helens (Johnston Ridge) | 1996 |

| 6—Mt. Hood | Multnomah Falls |

|

| 6—Wallowa-Whitman | Hells Canyon |

|

| 8—Chattahoochee | Brasstown Bald | 1963 |

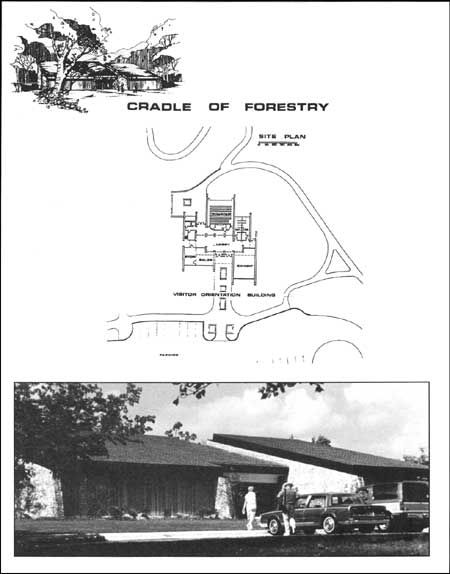

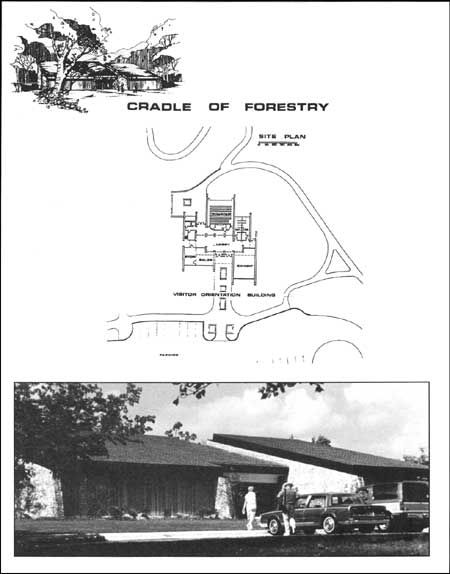

| 8—North Carolina | Cradle of Forestry (destroyed by fire) | 1964 |

| 8—North Carolina | Cradle of Forestry | 1984 |

| 8—Ozark-St. Francis | Blanchard Caverns | 1969 |

| 8—Chattahoochee | Anna Ruby Falls | 1988 |

| 8—Caribbean | El Portal del Yunque | 1996 |

| 8—George Washington | Massanutten |

|

| 8—Jefferson | Mt. Rogers | 1972 |

| 8—Jefferson | Natural Bridge |

|

| 9—Superior | Voyagers | 1963 |

| 9—Monongahela | Cranberry Mtn. | 1963 |

| 9—Ottawa | Watersmeet | 1968 |

| 9—Monongahela | Seneca Rocks | 1972 |

| 10—Tongass-Stikine | Mendenhall Glacier | 1961 |

| 10—Chugach | Portage Glacier | 1986 |

| 10—Tongass-Ketchikan | Ketchikan | 1994 |

|

Gallery of Forest Service Visitor Centers

|

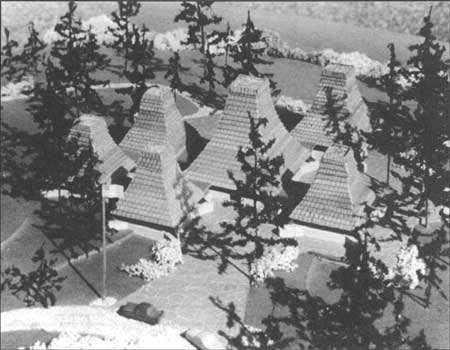

|

Figure 2-113. Conceptual model of Lake Tahoe Visitor

Center, Region 5 (1963)

|

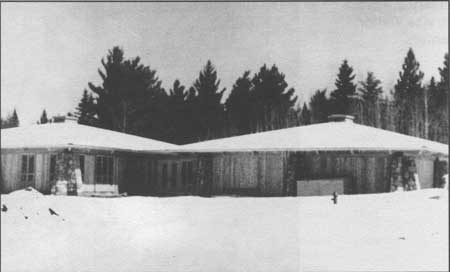

|

|

Figure 2-114. First (and only) building at Lake Tahoe Visitor Center (1964)

|

|

|

Figure 2-115. Ely Visitor Center, Ely, Minnesota, Region 9 (1963)

|

|

|

Figure 2-116. Sabino Canyon, Coronado National Forest, Region 3 (1963)

|

|

|

Figure 2-117. Original Cradle of Forestry, Pisgah National

Forest, Region 8 (1964)

|

|

|

Figure 2-118. Gila Cliff Dwellings Visitor Center, Gila

National Forest, Region 3 (1965)

|

|

|

Figure 2-119. West Yellowstone Visitor Center, Montana,

Region 1 (1966)

|

|

|

Figure 2-120. Red Canyon Overlook Visitor Center, Flaming

Gorge National Recreation Area, Region 4 (1966)

|

|

|

Figure 2-121. Big Lake Visitor Center, Apache National

Forest, Region 3 (1966)

|

|

|

Figure 2-122. Brasstown Bald, highest point in Georgia, Region 8 (1967)

|

|

|

Figure 2-123. Cape Perpetua Visitor Center, Siuslaw National Forest,

Region 6 (1967)

|

|

|

Figure 2-124. Deck and view from Cape Perpetua Visitor Center

|

|

|

Figure 2-125. Pactola Visitor Center, Black Hills National

Forest, Region 2 (1969)

|

|

|

Figure 2-126. Blanchard Cavern Visitor Center, Region 8 (1969)

|

|

|

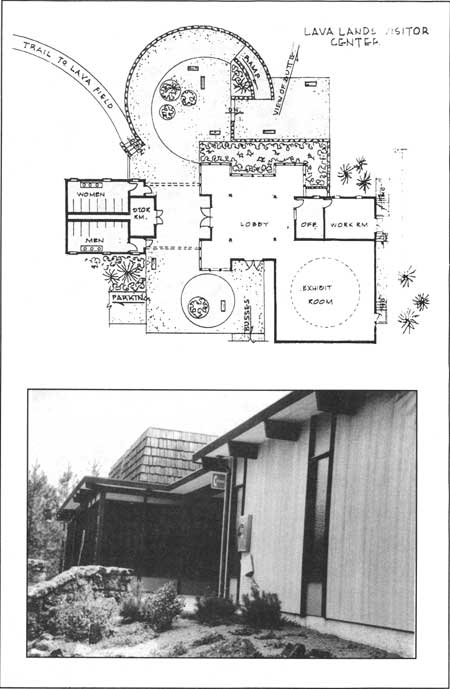

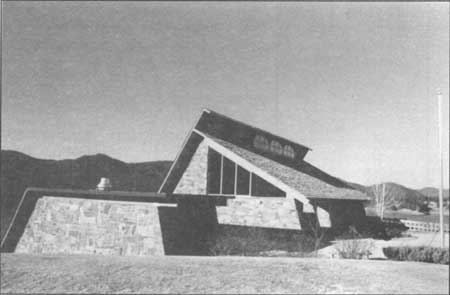

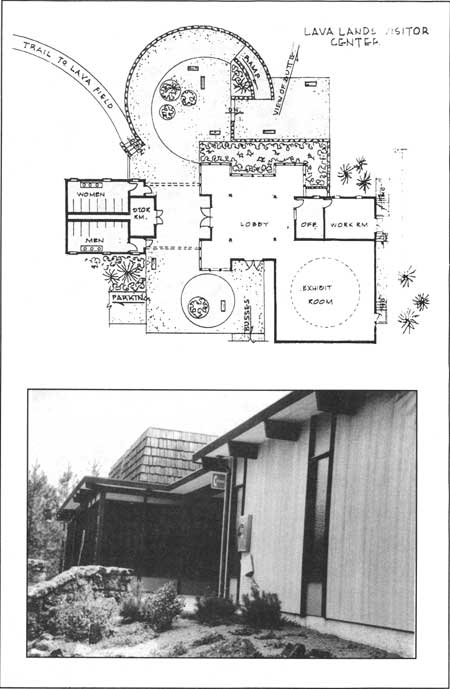

Figure 2-127. Lava Lands Visitor Center, Deschutes National

Forest, Region 6 (1975)

|

|

|

Figure 2-128. Rebuilt Cradle of Forestry Visitor Center,

Pisgah National Forest, Region 8 (1984)

|

|

|

Figure 2-129. Chilao Visitor Center, Angeles National Forest,

Region 5 (1980)

|

|

|

Figure 2-130. Mono Lake Visitor Center, Inyo National

Forest, Region 5 (1990)

|

|

|

Figure 2-131. Mount St. Helens Visitor Center at Silver

Lake, Region 6 (1986)

|

|

|

Figure 2-132. Mount St. Helens Vistor Center at Coldwater

Ridge (1993)

|

|

|

Figure 2-133. North Kaibab Visitor Center, Kaibab National

Forest, Region 3 (1991)

|

|

|

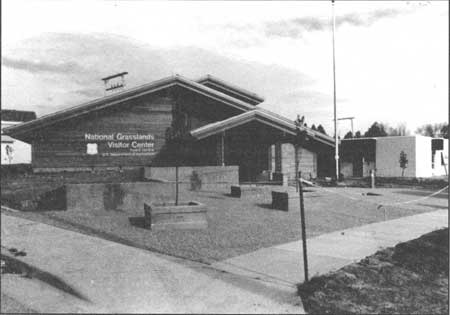

Figure 2-134. National Grasslands Visitor Center,

Wall Administrative Site, Nebraska National Forest, Region 2 (1991)

|

|

|

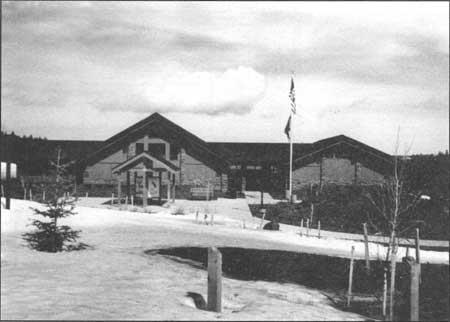

Figure 2-135. Burgess Junction Visitor Center, Bighorn

National Forest, Region 2 (1992)

|

|

|

Figure 2-136. El Portal Visitor Center, Carribean National

Forest, Region 8 (1996)

|

|

|

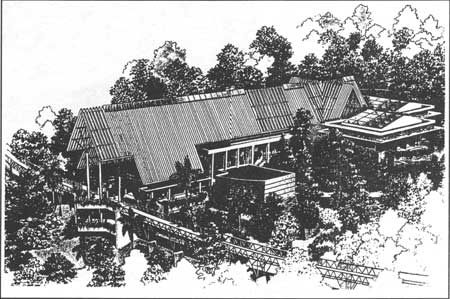

Figure 2-137. Prehistoric Prairies Discovery Center,

Crawford, Nebraska, Region 2 (1998)

|

|

|

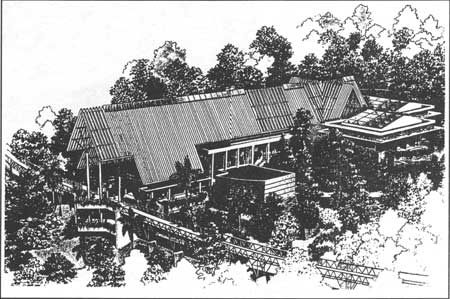

Figure 2-138. Grassy Hollow Visitor Center, Angeles

National Forest, Region 5 (1996)

|

Research Buildings

When the Forest Service was created in 1905, it was recognized that

research was needed to guide the new agency's efforts. European

experience, which provided the best example of forestry at the time, was not

an adequate basis for American forestry because of the different

species, climates, and social and economic conditions prevailing in the

United States. At that time, field studies were conducted throughout the

United States, but all of the investigators were headquartered in

Washington, DC. [1]

A significant change in the research organization occurred in 1908 with

the establishment of a system of forest experiment stations. The first

station was established at Fort Valley on the Coconino National Forest

in Arizona, with similar stations built in Colorado, Idaho, California,

Washington, and Utah. [2]

These "stations," however, were rather small and localized—more

like what were later called "field centers" or "work centers" or even

"experimental forests." In 1915, research in the Forest Service was

consolidated within the newly established Branch of Research. The first

regional forest experiment stations were the Appalachian and Southern

Forest Experiment Stations, which were established in 1921. In 1923, the

Lake States and Northeastern Forest Experiment Stations were

established, followed in 1924 by the Pacific Northwest Station and in

1925 by the Allegheny, Central States, and Northern Rocky Mountain

Stations. The California Station (1926), the Intermountain and

Southwestern Stations (1930), and the Rocky Mountain Station (1935)

completed coverage of the forested regions of the continental United

States.

In 1909, forest products research was centrally located at the

University of Wisconsin at Madison. This Forest Products Laboratory building

(figure 2-139) was built by the University for the Forest Service and was

dedicated in 1910.

|

|

Figure 2-139. Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin: original building

|

Early in its history, the Forest Service established experimental forest

reserves, areas set aside from normal day-to-day operations to study

various ecosystems through scientific controls. The first buildings

were similar to those constructed for the forest management buildings,

using the same style and materials. When the first stations were

created, they were all associated with universities; the buildings were

either college buildings on campus or rented facilities just off

campus.

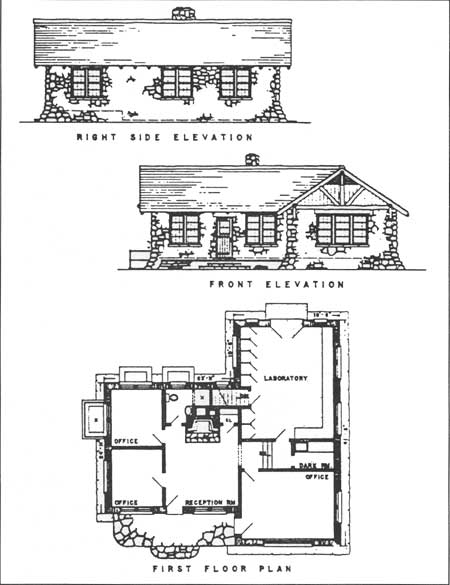

In the 1930's, as with administration buildings, there was a boom in

construction for research. Many of the scientific research facilities were

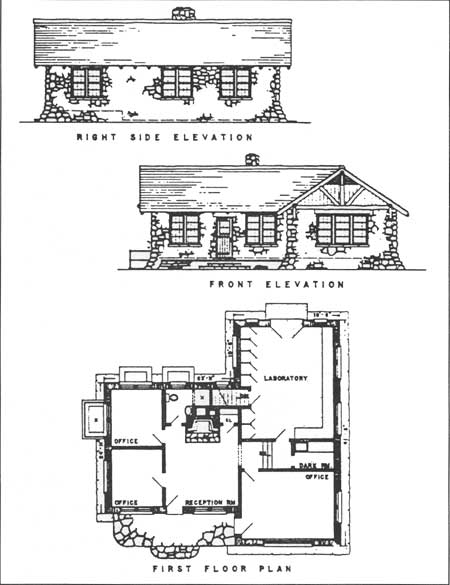

built by the CCC. Groben's 1938 "Acceptable Plans" book included a

research facility (figure 2-140).

|

|

Figure 2-140. Office and laboratory, Irons Fork Experimental Forest,

Mena, Arkansas, Region 8

|

In California, three notable complexes of buildings were constructed, as

was a unique structure at an experimental forest. The complex of

buildings at the Fresno Experimental Range was designed in the regional office to be

constructed of adobe blocks. Experts from Mexico were brought in to

teach the CCC construction crew how to mix, mold, sun dry, and build

with this southwestern construction material. North of Fresno, in

Placerville, the Forest Genetics Laboratory was constructed by the CCC

(figure 2-141). In southern California, the headquarters of the San

Dimas Experimental Forest in Glendora and a lysimeter on the

experimental forest were designed in the Regional Office and

constructed by the CCC.

|

|

Figure 2-141. Office and laboratory, Institute of Forest

Genetics, Pacific Southwest (PSW), Placerville, California (1938)

|

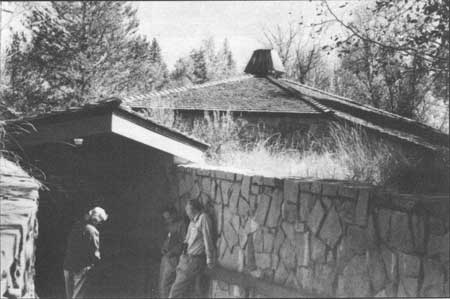

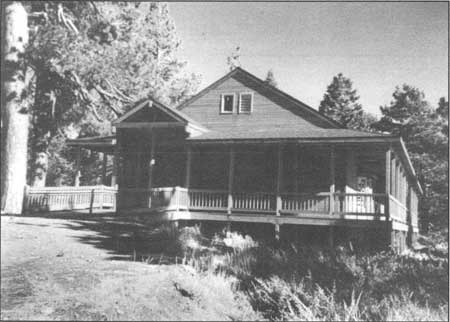

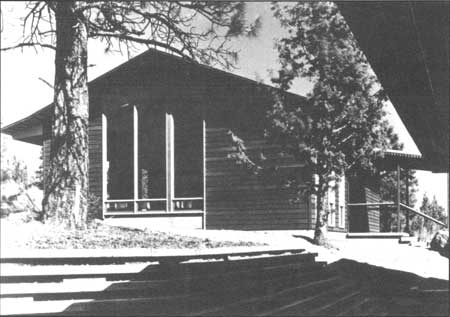

The headquarters building for the Priest River Experimental Forest in

Idaho's Panhandle National Forest (figure 2-142) was constructed in the

late 1930's. The buildings at this complex have been nominated for the

National Register of Historical Buildings. Figures 2-150 and

2-151 on page 162 show examples of other research building styles

of the 1930's.

|

|

Figure 2-142. Priest River Experimental Forest,

Priest River, Idaho (1939)

|

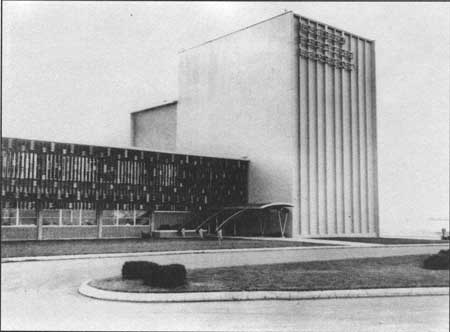

Between 1931 and 1932, a new laboratory building for the Forest Products

Laboratory was designed and constructed on the campus of the University

of Wisconsin. The laboratory was designed by the Chicago architectural

firm of Holabird and Root. Both Holabird and Root were graduates of the

Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris and the firm's background included the

steel framed Rand Tower and the Palmolive Building, early skyscrapers in

the commercial district of Chicago. The firm also designed the Chrysler

Building at the 1939 New York World's Fair.

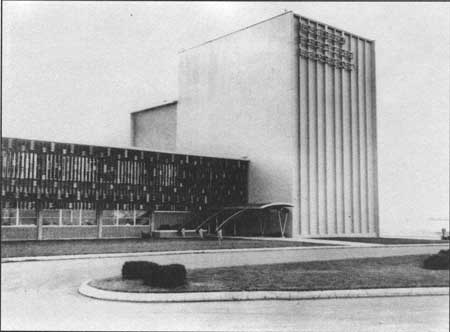

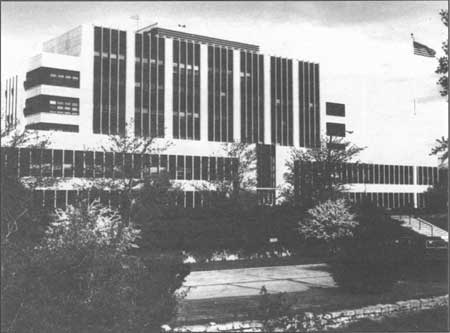

The building (figure 2-143) typifies the American Perpendicular or

Modernistic phase of the Art Deco style as it was applied to commercial

design. The building is detached, with a U-shaped plan. The frame of the

building is steel covered with concrete. The

exterior is faced with smoothly dressed white Indiana limestone blocks.

The windows are massed in groupings of four: one-over-one, double-hung

sashes with flat surrounds. Cypress-wood fins running the height of the

vertical faces flank each window and add a decorative and functional

detail. The fins shade the glass in the windows during the heat of the

day and reduce solar gain. Atop the vertical mass is a set-back

"penthouse" housing the building's mechanical systems. The roof is flat,

with a plain parapet, and there is no cornice decoration. This building

style is unique. The building entrance is from Walnut Street and is

called Gifford Pinchot Drive.

|

|

Figure 2-143. Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin: new

building constructed under WPA program (1932)

|

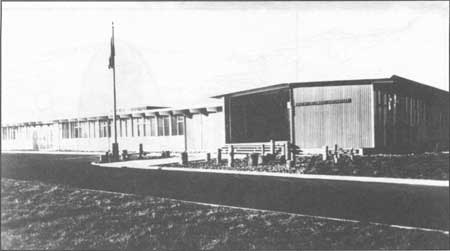

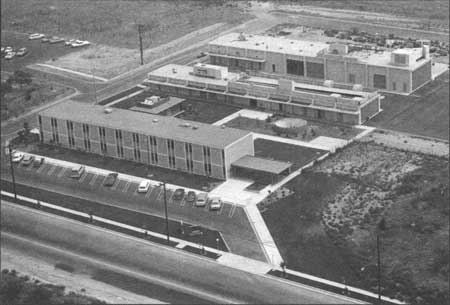

In the postwar years, the Forest Service set up two Engineering

Technology and Development Centers. One was located in Missoula,

Montana, and the other in Arcadia, California. At the outset, the main

function was development of road building and maintenance equipment.

Over the years this was expanded to firefighting, recreation, and

building systems and equipment. In the early 1970's, a new center for

the California group was constructed just outside the city of San Dimas

(figure 2-144).

|

|

Figure 2-144. Equipment Development Center, San Dimas,

California (1970)

|

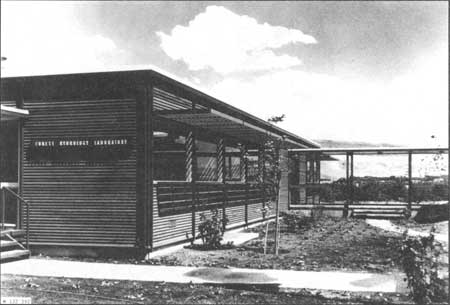

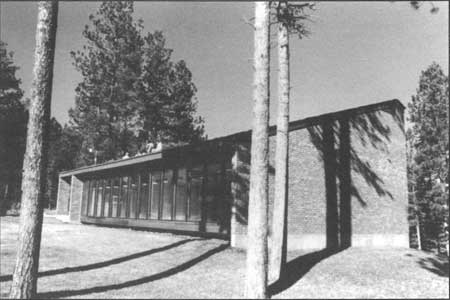

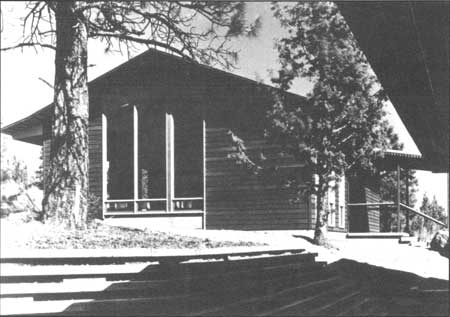

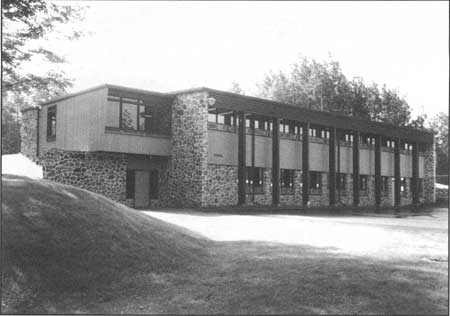

In the early 1960's, Benny DiBenedetto moved from his post as Regional

Architect for Region 6 to become Station Architect for the Pacific

Northwest Experiment Station. DiBenedetto almost immediately began to

design the new laboratory facilities at Bend and Corvalis, Oregon. His

work was so unique that it was published in national architectural

magazines (figures 2-145 and 2-146). Examples of other design

styles of the 1960's through the present can be found on pages 163

through 168.

|

|

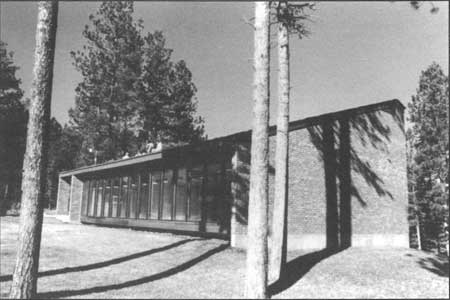

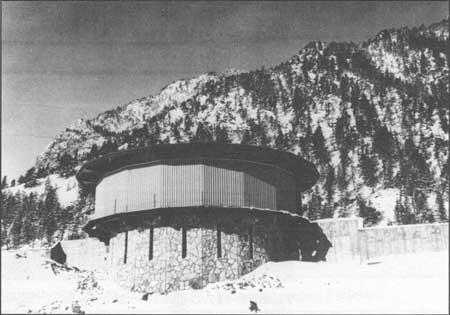

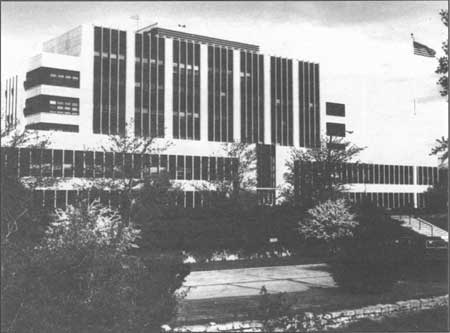

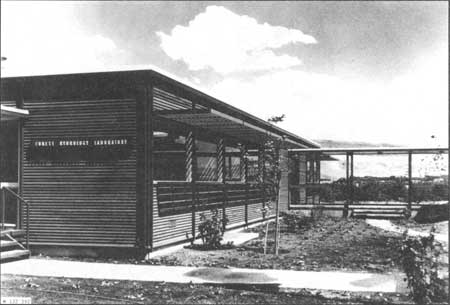

Figure 2-145. Silviculture Research Laboratory,

Bend, Oregon (1963)

|

|

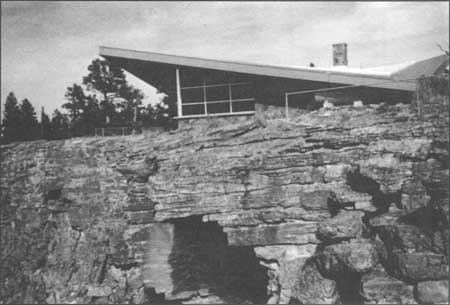

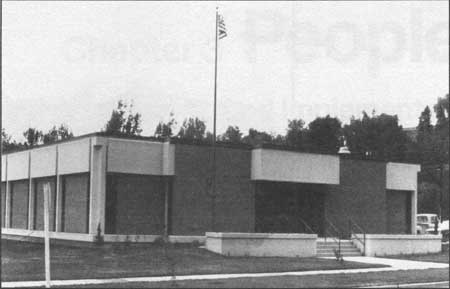

|

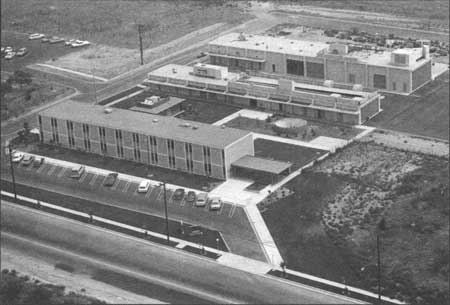

Figure 2-146. Forestry Sciences Laboratory, Corvallis, Oregon

(1963)

|

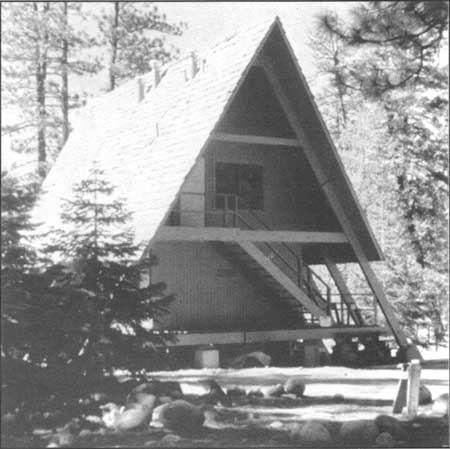

In the mid 1960's, a joint venture by the Southeastern Forest Experiment

Station and the Forest Products Laboratory produced several designs for

low-cost wood homes. The designers were Harold F. Zornig of Athens,

Georgia, and L.O. Anderson of Madison, Wisconsin. The various Regions

constructed several of these as prototypes to be used in public service

announcements. The estimated cost for construction was about one-half

the cost of standard-design tract homes of the time (figures 2-147

through 2-149). The actual construction costs were higher than

estimated.

Notes

1. Herbert C. Story, History of Forest

Science Research, Development of a National Program, p. 8.

2. Ibid., p. 13.

|

|

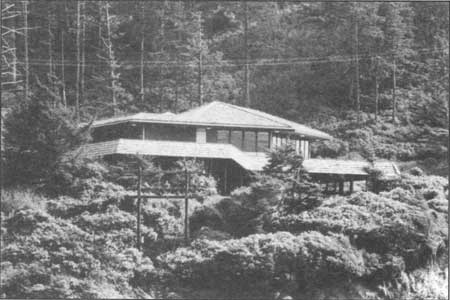

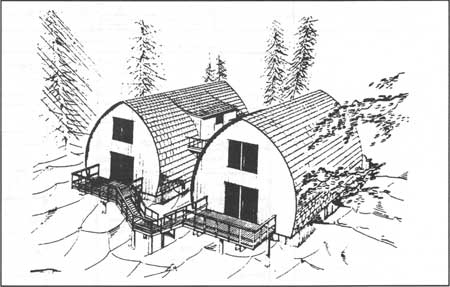

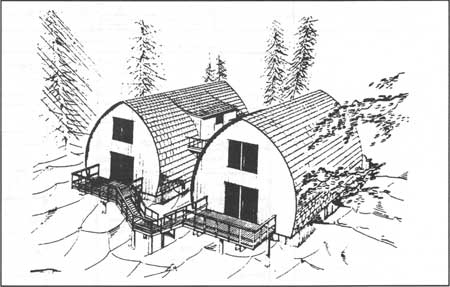

Figure 2-147. A Hillside Duplex of Wood: This interesting

design for a two-family home is intended particularly for sloping sites.

It provides a total of 900 square feet in each of the two units, approximately

half on each of two floors. The design is based on a pole-frame structure

with wood arches that can be built in a simple shop.

|

|

|

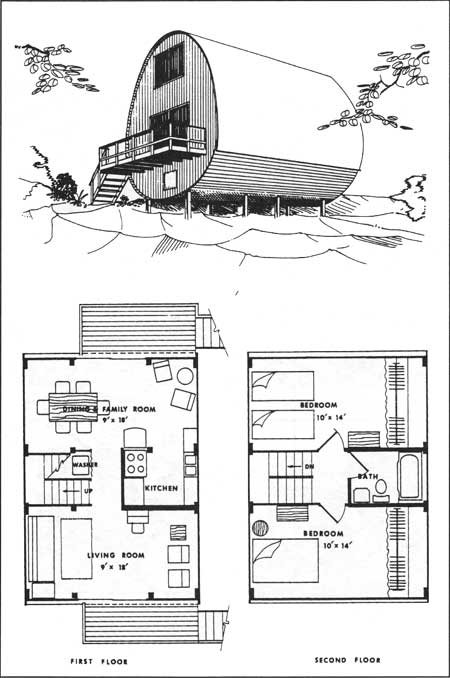

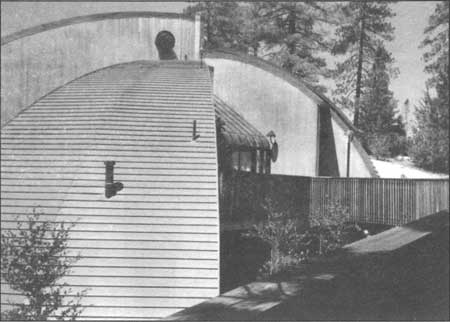

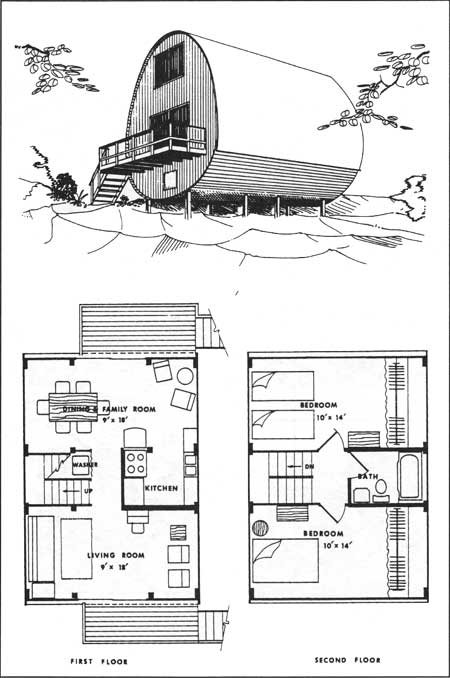

Figure 2-148. Tubular Home of Wood: This unusual home offers

attractive living space within its curved walls. It is intended for sloping

sites in rural areas. This home provides 1,000 square feet of floor area.

|

|

|

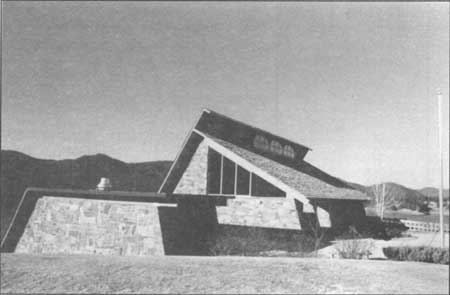

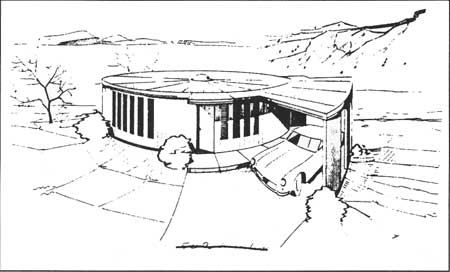

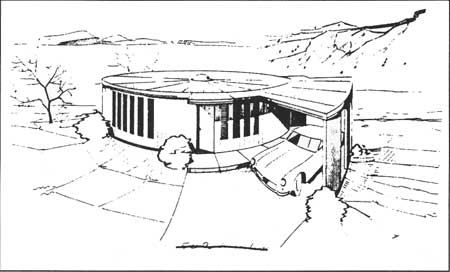

Figure 2-149. A Round House of Wood: This unique design provides a

three-bedroom home with 1,134 square feet of living area. It is designed for a

flat site. A smaller version provides three bedrooms and a total area of 804

square feet.

|

Gallery of Forest Service

Research Buildings

|

|

Figure 2-150. Combined office, laboratory, and bachelor's

quarters, Roscommon, Michigan (1934)

|

|

|

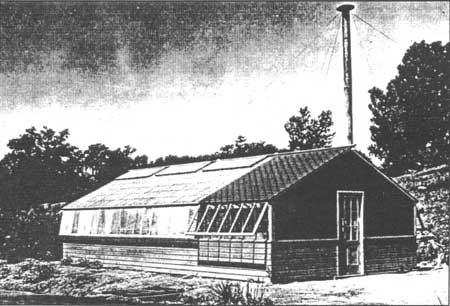

Figure 2-151. Greenhouse, San Juaquin Ranger PSW,

O'Neals, California (1936)

|

|

|

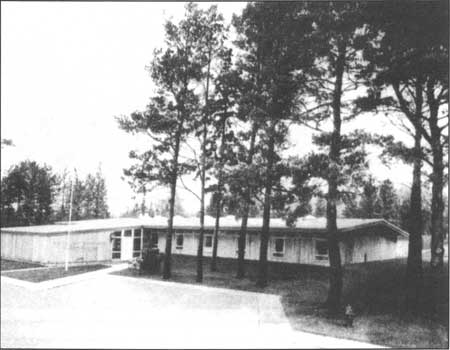

Figure 2-152. Northern Institute of Forest Genetics

Reinlander, Wisconsin (1960)

|

|

|

Figure 2-153. Headwaters Forest Research Center, Grand

Rapids, Minnesota (1960)

|

|

|

Figure 2-154. Northern Forest Fire Laboratory, Missoula,

Montana (1961)

|

|

|

Figure 2-155. Shleterbelt Laboratory, Bottineau, North

Dakota (1962)

|

|

|

Figure 2-156. Forest Hydrology Laboratory, Wenatchee,

Washington (1963)

|

|

|

Figure 2-157. Laboratory, Durham, North Carolina (1963)

|

|

|

Figure 2-158. Moscow Laboratory, Moscow, Idaho (1963)

|

|

|

Figure 2-159. Silviculture Laboratory, Sewanee, Tennessee (1966)

|

|

|

Figure 2-160. Provo Laboratory, Rocky Mountain Station,

Provo, Utah (1969)

|

|

|

Figure 2-161. Redwood Sciences Laboratory, Arcata,

California (1971)

|

|

|

Figure 2-162. Corvallis Laboratory, Corvallis,

Oregon (1978)

|

|

|

Figure 2-163. Fresno Laboratory, Region 5 (1985)

|

EM-7310-8/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 08-Jun-2008

|