|

A History of the Architecture of the USDA Forest Service

|

|

Chapter 3

People: Leaders and Implementers

"The final test of a leader is that he leaves behind him in other men the conviction and will to carry on."—Walter Lippmann, Roosevelt Has Gone

The Forest Service Architects

Current Architects (1999)

|

Rudy Brown Bruce Crockett Daryl Dean Lee Deeds Dave Dercks, Region 9* Ken Duce Dave Faulk, Region 2* Nancy Freeman Dana Henderson Maurice Hoelting Josiah Kim, Washington Office Jane Kipp |

Jeff Klas Kurt Kretvix, Region 3* Keith Lee Gil Levesque Hal Miller Oswaldo Mino Wilden Moffett, Region 4* Thad Schroeder Jo Ann Simpson, Region 6* Kathie Snodgrass William A. Speer, Jr., Region 8* Adele Tsunemori |

Retired Architects (1999)

|

Arthur F. Anderson, Region 1* S.A. Axtens, Region 2* Jim A. Calvery, Region 9* Harry W. Coughlan, Region 1 * Don Critchlow A.P. "Benny" DiBenedetto, FAIA, Region 6* Clyde P. Fickes, Region 1* Bill Fox, Region 1* W. Ellis Groben, Washington Office* John R. Grosvenor, Region 5* Glenn Hacker Alton Hooten, Region 6* W. Earle Jackson, Region 2* Keplar B. Johnson, Region 5* Harry Kevich, Region 5* |

Joe Lazaro Bob LeCain, Region 1* Joe Mastrandrea, Region 6* Allan Mitchell Dick Modee George Nichols, Region 4* Nels Orne, Region 9* A.E. Oviatt (Research) Ken Reynolds, Region 6* Bob Sandusky, Region 5* William Turner, Region 4* Art Ulvestad Wes Wilkison, Region 2* Jim Wilson Harold Zorning (Research) |

*Denotes Regional Architects

|

|

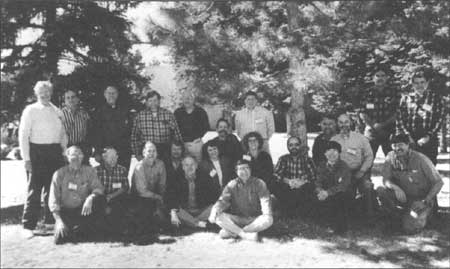

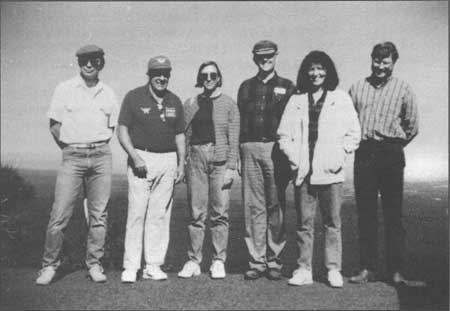

Figure 3-1. Architects' Gathering, Albuquerque, New

Mexico, 1986 Front Row: Thad Schroeder, Region 2; Maurice Hoelting, Region 8; Dave Dercks, Region 9; unidentified (National Park Service); Wilden Moffett, Region 4; Joe Mastrandrea, Region 6; unidentified (National Park Service). Second Row: Bruce Crockett, Region 1; Don Critchlow, Region 8; William A. Speer, Region 8; Jo Ann Simpson, Region 6; Glenn Hacker, Region 1; unidentified (National Park Service); George Lippert, retired Civil Engineer Third Row: Lou Archambault, Region 3; Dave Dodson, Region 1; Hal Miller, Region 6; Jim Wilson, Region 6; John R. Grosvenor, Region 5; Ken Duce, Region 1; Dave Faulk, Region 2; Lee Deeds, Region 1; Bob Sandusky, Region 5; Keith Lee, Region 5. |

Architects Who Left the Forest Service

|

Lou Archenbault, Region 3* Tom Baltzell Albert Biggerstaff Jerome Brewster Bill Bruner Pam Chang Byron Cochran Dave Dodson, Region 1* Ann Dunn Mari Ellingson Ward Ellis Roy Ettinger Dale Farr Linn Argile Forrest, Region 10* Dave Frese Howard Gifford Dave Hall Gunnard Hans (Forest Products Laboratory) Bill Headley Jerry Heyers Bill Hohnstein |

Duane Hoochins Charles Jaka George Kirkham, Region 3* Arthur Longfellow Dick Lundy Mike Madias Tom Morland Harold Nelson Bill Peterson George Raach Neal Sands Deford Smith, Region 8* Cal Spaun Si Stanich Allan Tucker William Irving "Tim" Turner, Region 6* Fred Wagoner Bill Wells R.M. Williams Judy Winfrey Dean Wright Ron Wylie |

*Denotes Regional Architects

Regional Architects

|

Region 1 Region 2 Region 3 Region 4 |

Region 5 Region 6 Region 8 Region 9 Region 10 Washington Office |

*George Nichols served both Region 3 and Region 4 from Ogden.

|

|

Figure 3-2. Architects' Gathering, Denver, Colorado,

1997 Front Row: Dave Faulk, Region 2; Wilden Moffett, Region 4; Thad Schroeder, Region 2; Lee Deeds, Region 2; Maurice Hoelting, Region 8; Nancy Freeman, North Carolina; Randy Warbington, Mechanical Engineer, Region 8; Kathie Snodgrass, Region 1; Ken Duce, Region 1; Josiah Kim, Region 1; Bruce Crockett, Region 1. Second Row: Jim Wilson, Region 6; Jeff Klas, Region 3; John R. Grosvenor, Region 5; Gil Levesque, Region 4; George Lippert, retired Civil Engineer; Kurt Kretvix, Region 3; Daryl Dean, Region 9; Hal Miller, Region 4; Dana Henderson, Region 5; Gary Gibson, Architectural Technician, Region 4; William A. Speer, Region 8. Not in Photo: Keith Lee, Region 5; Jane Kipp, Region 1; Oswaldo Mino, Region 1. Not at Gathering: Jo Ann Simpson, Region 6; Rudy Brown, Region 2; Adele Tsunemori, Region 2. |

The following sections in this chapter are a compilation of memoirs by various past and present Forest Service architects. Their experiences were either written by the architect or by John R. Grosvenor based on interviews he conducted.

Editing in these sections was minimal; however, we made the sections consistent with Government and Forest Service Engineering styles and format. In some instances, spellings of people and places and exact dates could not be verified and can only be left up to the individual architect's recall.

W. Ellis Groben

Washington Office Architect (1933-1953)

Ellis Groben was a product of the East, a native of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He attended the University of Pennsylvania for undergraduate architectural training and then went to the Ecole des Beaux Arts School of Architectural Design in Paris, France, for his postgraduate education.

He entered into apprenticeship training in and around Philadelphia. His early practice was with architectural firms on the east coast. He was hired as Chief Architect for the city of Philadelphia, but a political upset there forced him to seek other employment. After spending some time doing residential design, he was employed by T.W. Norcross, Chief Engineer of the Forest Service, as the national consulting architect. When he arrived he looked the part, with a flowing mustache and goatee.

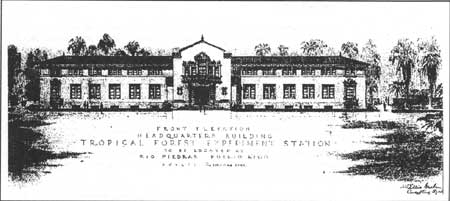

In the early years, Groben produced concepts for Forest Service structures, which were detailed by his draftsman, Ed Hamilton. Groben enjoyed making elaborate renderings of his building concepts; his drawing of the proposed headquarters building for the Tropical Forest Experiment Station in Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico (figure 3-3), hangs in the lobby of the building today. He also spent considerable time relocating his automobile about the streets of southwest Washington, DC, to minimize his violations of the overtime parking ordinance. [1]

|

| Figure 3-3. Rendering of the Tropical Forestry Building, Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico, by Ellis Groben (1939) |

Almost all we know of Groben's architectural philosophy comes from three major documents he signed. The first of these and the most extensive is "Acceptable Plans for Forest Service Buildings," dated 1938. This is a large collection of plans and elevations selected by Groben from all of the various Regions of the Forest Service and other Federal land management agencies. He states in the Preface: "The majority of plans and elevations have been reproduced in their entirety, as prepared by the respective regional offices; others have been slightly modified to correct or improve minor details without changing their general scheme."

The second document, written in 1940, is "Architectural Trend of Future Forest Service Buildings." In the first paragraph, Groben states: "The external design of Forest Service buildings calls for a greater display of imagination and inventive genius than heretofore, in order to give them sufficient individual character to definitely express their purpose and the particular Federal agency to which they belong."

He was upset by the eclectic trends of the architectural profession of this time. He said: "The almost universal practice, now commonly in vogue in a number of Regions, of always employing the conventional urban styles of architecture for Forest Service buildings generally, could be discontinued advantageously for styles which are more expressive of the Forest Service itself, and, at the same time, more appropriate to the diverse conditions, respective locations and particular environments in which they are to be erected." He goes on to say: "No one architectural style can serve universally to adequately represent any particular Federal agency because the country itself is too vast in extent and too varied in character to permit of it with any degree of success. For example, the Colonial style is incongruous in regions where, due to traditional usage, it has been found that the Mexican, Spanish, or Ranch types are appropriate and practical. The contrary is equally true. As in most of his documents, he follows up with plans to explain.

He concludes this document with: "Engineering, Washington Office, welcomes the opportunity of reviewing any sketches which may be submitted for its special consideration, comments and suggestions, etc., in advance of actual construction in order to assist insofar as possible, in improving matters of architectural design.

The last of the three documents, the "Improvement Handbook," focuses on the construction and maintenance of Forest Service buildings. George Nichols, Regional Architect, Region 4, prepared most of the text from reviewing handbooks and bulletins from the various Regions. Groben states in the Preface: "The purpose of this handbook is to make available the methods and standards recognized as good practice in building structural improvements on the national forests to Forest Service engineers, architects, and men engaged in construction."

All three of these documents provided strong leadership to the new architects emerging in all of the Forest Service Regions. As stated in chapter 1, Eras, there is no record of a Forest Service architect prior to the 1930's. Ellis Groben established an effective standard from his position as National Consulting Architect of the agency. Without his voice from Washington, DC, the course of the history of Forest Service architecture could have been as diverse as the many forests in this Nation. Groben put his skills as both designer and public administrator to work guiding the Forest Service as it worked to create its own style of architecture.

In the summer of 1944, Groben made his first visit to a forest west of the Mississippi: he went to Montana on a monitoring trip, meeting with Clyde Fickes. Fickes thought some of his reactions to western conditions and practices were most interesting, and at times very amusing. Groben remarked time and again as they drove through the forests about the amount of dead timber lying on the ground. Groben asked why it wasn't being gathered up and being put to some use. As a student in France and Germany, he had observed how the ground or floor of the forests was kept clean and free of debris. Fickes found it difficult to convince him that we were not overlooking a productive phase of forest management. [2]

Groben had one bad habit that was disliked by the architects in the various Regions. When the architects sent him copies of preliminary plans and sketches for his review and recommendations, he would make his comments and corrections in red pencil on the original documents. These included fully rendered color drawings that were ruined by Groben's additions and comments. This was the way professors in architecture schools in Europe and the United States dealt with their students.

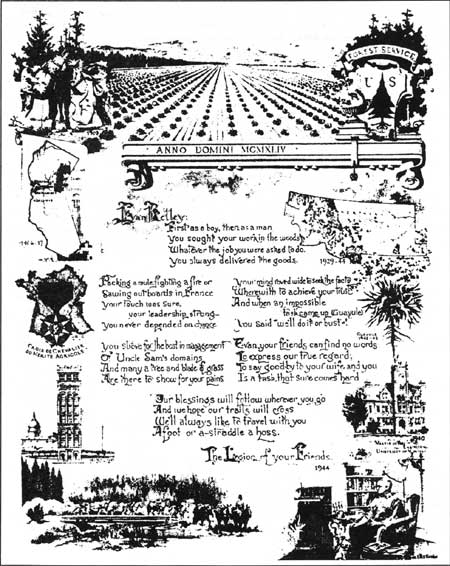

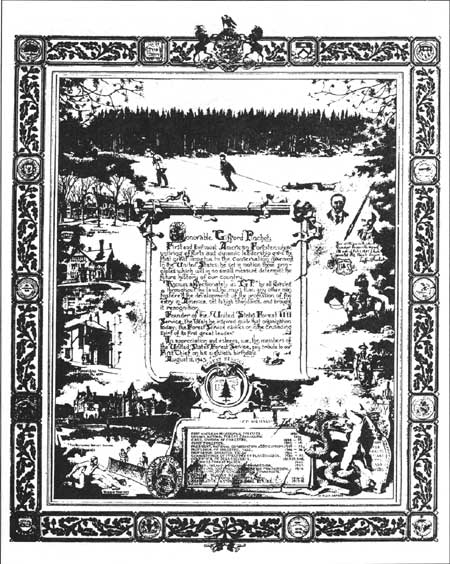

Groben was not only an outstanding architect who designed many public buildings, but he was also an artist of real ability. He prepared plaques for Gifford Pinchot, to commemorate his 80th birthday, and Evan Kelly, upon his retirement. Some of his artwork is illustrated on the following pages (figures 3-4 through 3-6).

|

| Figure 3-4. Drawing by Ellis Groben to commemorate the retirement of Evan Kelley (1944) |

|

| Figure 3-5. Drawing by Ellis Groben to commemorate the 80th birthday of Gifford Pinchot, former Chief of the Forest Service (1945) |

|

| Figure 3-6. Poster drawn by Ellis Groben to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Forest Service (1955) |

Notes

1. USDA Forest Service, The History of Engineering in the Forest Service, p. 362

Clyde P. Fickes

Regional Architect, Region 1 (1929-1944)

Clyde Fickes was born in Nelson, Nebraska, in 1884. He grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, spending summers on a farm in Bedford County with his maternal grandmother. He attended Ohio Northern University, majoring in engineering. After graduation, he went to Kalispell, Montana, where he lived with an uncle.

Fickes was appointed a Forest Guard on July 6, 1907. He furnished a saddle and packhorse and was assigned to work with D.C. Harrison, a topographer, to survey and plat administrative site withdrawals.

For the next 17 years he worked on several forests in Region 1 and was assigned duties in various aspects of forest management. When Clyde transferred to the Madison National Forest, one of his first tasks was to learn how to drive the Government-owned Model T Ford. "On a forest like the Madison," Clyde said, "good transportation was a necessity. Any place one wanted to go was 20 to 40 miles, so it was not a very good saddlehorse chance. Four miles an hour against 40, and a Ford could be driven cross-country on at least half of the forest, especially if the Ford was equipped with a Ruckstell axle"

After Clyde had worked on the Madison for a period of time, the following announcement was posted in the Sheridan Office:

Fickes Family Departs for Sandpoint—C.P. Fickes, of the local Forest Office, who has been transferred to the Pend Oreille National Forest with headquarters at Sandpoint, Idaho, expects to leave today or tomorrow for his new station. Mr. Fickes was transferred to the Madison Forest from the Nezperce on March 5, 1924, and has since that time occupied the position of Assistant Supervisor on the Madison Forest.

"In due time I reported to Forest Supervisor Ernest T. Wolf at the Pend Oreille National Forest in Sandpoint, Idaho, and met Assistant Supervisor L.F. "Duff Jefferson, Forest Assistant George M. DeJarnette, and Chief Clerk Walter W. Schwartz. The office was in a storeroom on the ground-floor level, with a private office partitioned off for the Supervisor. The forest was in need of improvements of all kinds, and my first job was to acquaint myself with what we had and then help to prepare overall plans for future development of the forest. We had a very light fire season in 1927, so I was able to visit all the ranger districts and visit with rangers about their improvement problems. The Port Hill District was allotted money for a lookout house on Smith Peak for which we did not have any construction plans.

"My father was a carpenter and builder, and I virtually grew up among carpenter shop shavings and small building construction. I drew up some detailed plans for a 12- x 12-foot building of frame construction with a 6- x 6-foot cupola, and ordered some lumber and hardware. Frank Casler hauled it up to the Smith Creek Ranger Station. At that time there were only half a dozen or so satisfactory, improved fire lookouts on the Idaho forests of Region 1. At that time the Region did not have any kind of structural plans and specifications for a lookout structure. Region 6, at Portland, Oregon, had a plan for a 12- x 12-foot building with an observation cupola on top, which was developed for that Region by some architectural engineer. The estimated cost of that building was from $1,200 to $2,000 to construct. I had prepared plans for a ready-cut lookout, and the cost of materials was less than $100. When I returned to the office after this chore, I was informed that the Regional Office wanted me to come in on a detail to design a lookout house for the Region. Joe Halm, a draftsman in Engineering, did all the tracing for the ready-cuts.

"Then it was decided that I should become a part of the Regional Office staff in the Office of Operations. In May 1929, I moved my family from Sandpoint to Missoula. I became the person supervising the design and construction of all improvements (trails, telephone lines, buildings, campground layouts, and later radio communications).

"In order to take care of the volume of work generated by the new emergency appropriations and the CCC's, it was necessary to set up an architectural section for the design and planning of major improvements. William J. (Bill) Fox came to us via Butte and the University of Washington at Seattle as a professional architect. Bill eventually supervised a staff of six or seven architectural draftsmen under my general supervision. His first major job was developing the plans for development of the Remount Depot layout.

"Early in my assignment to the Regional Office, it became apparent to me, from my contact with the rangers in the field, that they needed some sort of manual or handbook to which they could refer for information of all sorts on improvement, construction, and maintenance work. I set to work gathering all kinds of illustrations showing how to frame a building wall, how to cut a rafter, what kind of nails to use, how to mix concrete, how to build a brick chimney, what kind of hardware to use and how to order from the dealer, how to build concrete forms, a chapter on log building construction, and the most practical way to string telephone wire and install telephones. This developed into a letter-sized mimeographed volume about 1-1/2 inches thick, which we called the Improvement Handbook. This became the rangers construction and maintenance bible. The manual also contained a section on log building construction, which I eventually developed into the Log Construction Handbook. It was printed by the Bureau of Government Printing and sold over 100,000 copies. Along about 1968, the University of Alaska issued a reprint of my Log Construction Handbook without giving me any credit. Of course, Government publications are not copyrighted.

"In 1936, we were bodily transferred to the Office of Engineering under Fred Theime. We also took over the direct supervision of ranger station construction.

"The winter of 1936-37, I attended, with several others from Region 1, a conference of Forest Service engineers and architects at the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin. The first day we had lunch at the cafeteria: while standing in line, I was introduced to the man next to me. The man in front of him turned around and looked at me and said, 'Are you the Clyde Fickes who was at Ohio Northern University in 1903?' It was Jim Brownlee, Regional Engineer at Denver. He was a graduate of Ohio Northern's Engineering School; he and I had been together in a campus fracas in which engineers, pharmacists, and lawyers took on the rest of the campus in a graduation fracas.

"Ted Norcross, Chief of Engineering in the Washington Office, was there, and he had some concerns over the revision of the Trail Manual and the new Telephone Handbook that were about ready for printing. Since I had made some constructive, not to mention critical, comments and suggestions about the makeup of both of them, he arranged for me to go back to Washington with him and help get the job done, which I did." [1]

Fickes was named by Jim Byrne as the lead engineer for the construction of the facilities for the Guayule Rubber Project in 1942 (where he worked from February until November). Major Kelly, his supervisor, wrote: "Clyde Fickes has quit the project for good. He has done a great service here. All whom he has served may not realize the obstacles under which he worked; however, he made for the project a lot of progress that would not have been achieved had it not been for his practicality and drive."

Fickes returned to the Missoula Regional Office, where he completed his Forest Service career. In June 1944, he was offered a promotion to a job with the Treasury procurement organization with a substantial increase in salary that he could not turn down. He retired from Government service on June 30, 1947.

Notes

1. Excerpts from Clyde P. Fickes, Forest Ranger Emeritus, Recollections, 1972.

William Irving "Tim" Turner

Forest Service Architect (1933-1951)

William Irving Turner, called "Tim," was born in Oregon in 1890 and attended junior high school and high school in Portland. His training in architecture began in the architectural firm of David C. Lewis in Portland, where he worked from August 1912 to July 1916. Turner was also studying during that time in Portland in a "Beaux Arts Atelier" in design. This school was a design studio affiliated with the Society of Beaux Arts Architects that offered Oregon's first formal classes for would-be architects. From May 1917 until May 1919, Turner spent 2 years in the military, stationed in Belgium. After the war, Turner returned to Portland and worked for D.L. Williams, a firm specializing in industrial buildings, and DeYoung and Roald, a firm specializing in church and school design, from January 1922 until March 1925.

In 1925, Turner moved to Los Angeles to work for Schultze & Weaver and supervised the architectural work for the major structures (banks, clubs, hotels, and office buildings) that the firm was building. In 1928, Turner returned to the Northwest and worked for Victor W. Voorhies, an architectural firm in Seattle. One of the major structures designed by Voorhies that Turner worked on was the Vance Building in Seattle in 1929. Turner's next move was to Phoenix, Arizona, where he spent 2 years, from September 1931 until August 1933, as the field representative for E. Heitschmidt, a Los Angeles architectural firm, directing construction work on the Arizona Biltmore Hotel, a million-dollar project of William Wrigley's, designed by Albert Chase McArthur and built by the Arizona Biltmore Corporation.

Turner returned to Oregon in the fall of 1933 because of the Depression's devastating effect on the architectural and building trades. He spent a month working for the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads in Portland as an assistant engineer. He accepted his first temporary appointment as "foreman" (architect) with the Forest Service on December 24, 1933. His services were needed in the Regional Office, for a period not to exceed 3 months, to assist in the construction of a new Forest Service warehouse in Portland. [1]

In 1934, Regional Engineer Jim Frankland set up an architectural section headed by Tim Turner. This unit developed standard plans for offices, warehouses, guard stations, shops, residences, and other buildings in a distinctive "Cascadian" architectural style for construction by CCC work-forces. Turner supervised 8 to 10 architects and draftsmen. [2]

Turner provided leadership to the Architectural Section during the full CCC period and through World War II. Turner died in 1950. One of his most notable designs is the Timberline Lodge (see the section on Timberline Lodge in Chapter 2).

|

| Figure 3-7. Residence building designed by Tim Turner |

Notes

1. Wood, Mount Hood's Timberline Lodge: An Introduction to Its Architects and Architecture, pp. 16-19.

2. USDA Forest Service, History of Engineering, p. 500.

Linn Argile Forrest

Regional Architect, Region 10 (1934-1952)

Linn Forrest was born on August 8, 1905, in Bucyrus, Ohio. He attended Franklin High School in Portland and the University of Oregon. Although he did not complete his degree, his major subject was architecture. In addition to attending school, Forrest supervised construction of the First Baptist Church of Eugene and worked for F. Mason White, architect.

After leaving the University of Oregon in 1927, Forrest worked as chief draftsman for architect Hugh Thompson in Bend, Oregon, until 1928, when he enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to study architectural and structural design. His decision to attend MIT was perhaps influenced by the example of Ellis F. Lawrence, founder and dean of the School of Architecture at the University of Oregon, a desire for an analytical study of the past as the best guide to the future, and for training in the French academic tradition, including Beaux Arts design methods, a training received by Lawrence and by three of Portland's most influential architects: Ion Lewis, William M. Whidden, and Morris H. Whitehouse, all MIT graduates.

After his return to Portland, Forrest worked as architectural draftsman with architect Roi L. Morn until 1929. The types of work there included commercial buildings, residences, theaters, and schools; design of furniture suites, ornamental bronzes, and cast stone; and planning the proposed layout for Morningside Hospital.

Forrest entered the firm of Whitehouse, Stanton & Church in 1929 and was responsible for all phases of architectural work: preliminary sketches, perspective scale, and full-size drawings and supervision in the shops and on the job. The types of work included schools, hospitals, large residences, a U.S. Federal Courthouse building, and commercial buildings.

The quality of Forrest's work must have been thought exceptional among members of the architectural community, for on June 23, 1931, he was awarded the first Ion Lewis Traveling Fellowship. Ion Lewis, FAIA, retired architect of Portland, who with his partner, the late William H. Whidden, was responsible for much of the best work in Portland during the 40 years of their practice as a firm, established the grant in 1930. Forrest was one of three candidates for the award, which was open to Oregon architects between 20 and 30 years of age who were graduates of schools of architecture or had at least 6 years of architectural experience. It was to be an annual award by the University of Oregon, with the Dean of the School of Architecture and two members of the Oregon Chapter of the American Institute of Architects as trustees.

After spending a year traveling in Europe, Forrest returned to Portland in June 1932 at the depth of the Depression. He was eager to share his observations on the periods of architecture he had studied and planned an exhibition of his sketches.

In light of the reality of the economic situation, he noted, "We did anything in those days just to survive" and found work on a relief project for the city of Portland. It was there he met Tim Turner and worked with him in compiling data on underground services in downtown Portland. They also were in charge of a group collecting data and making measured drawings preparatory to redesigning several blocks of buildings facing on a proposed waterfront esplanade. It was during this period that Forrest obtained his Oregon State architect's license.

In June 1934, Forrest was working with the War Department's Bonneville Dam project as a draftsman. He left the Bonneville Dam project in February to take a position with the Forest Service.

In his first Forest Service position, he compiled a handbook of acceptable building designs for Region-wide use. He also designed recreation facilities such as ski resorts, bathing facilities, and related structures. [1]

When Tim Turner, Gif Gifford, and he were assigned to work on the Timberline Lodge project, Forrest was the youngest member. Although the three of them were given a very small space to work in, they discussed things pro and con without argument and worked very well together. Forrest developed floor plans and elevations, including the general layout of the headhouse. Working drawings of the plans and elevations of the lodge were signed "L.A.F." (see figure 2-103 on page 125). [2]

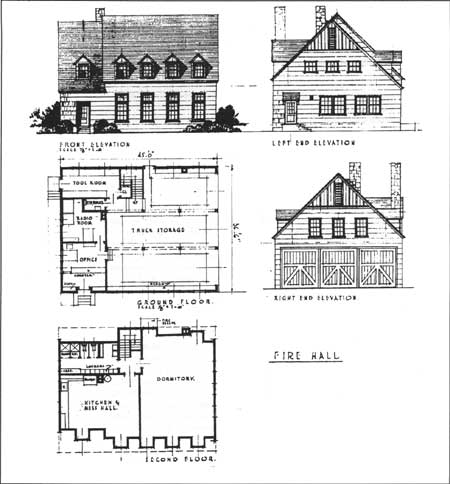

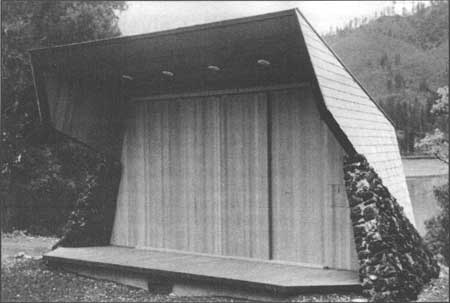

Turner left the office to be the field representative during the construction of the lodge. Gifford and Forrest were left in Portland to design other buildings for the CCC program (figure 3-8 shows one example). Until the CCC program was disbanded in 1942, many administration and recreation buildings were designed and constructed.

|

| Figure 3-8. Firehouse designed by Linn Forrest, Region 6 (1942) |

In 1946, Forrest was transferred to Alaska to become Regional Architect and to develop buildings similar to but smaller than those in Region 6. The Forest Service work was not challenging architecturally, so Forrest left the agency in the late 1940's. [3] In 1952, he opened a private office in Juneau, Alaska. In 1960, his firm, which then included his son, Linn, Jr., was selected to design the visitor center for the Mendenhall Glacier, just outside of Juneau (see figure 2-108 on page 132), and the restroom facility for the Portage Glacier, just outside of Anchorage on the Chugach National Forest.

A.P. DiBenedetto sponsored Forrest's election to the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Architects in 1979 for his design work on Timberline Lodge and the Mendenhall Glacier Visitor Center. Forrest died in June 1987 at the age of 81.

Notes

3. Dick Forrest, "A Tribute to my Father, Linn Argile Forrest," p. 3.

Keplar B. Johnson

Regional Architect Region 5 (1937-1962)

Keplar Johnson was born and raised in northern California. After high school, he attended the University of California at Berkeley, majoring in architecture. He was a classmate of William Wurster and Julia Morgan, and he admired and respected the work of both. After graduation, he worked in various small architectural offices in San Francisco. In 1937, times were extremely hard for private architects and Johnson applied for a newly established Forest Service position in San Francisco. He started working in the Engineering Department located in the Ferry Building at the foot of Market Street. He was a registered architect in the State of California.

Johnson took over the legacy left by the private architects Blanchard and Maher. They had produced many designs for all types of buildings to be constructed by the CCC program in California. The program was still in full swing when Johnson started, and his main tasks were to modify these designs for specific sites throughout California. As the workload increased, he hired two architectural draftsmen to assist in the production work. R.M. Williams and Arthur G. Longfellow both were young graduate architects who also did some design work as well as most of the drafting of the buildings Keplar designed. Art Longfellow moved on to Region 2 in Denver, Colorado, where he produced several designs.

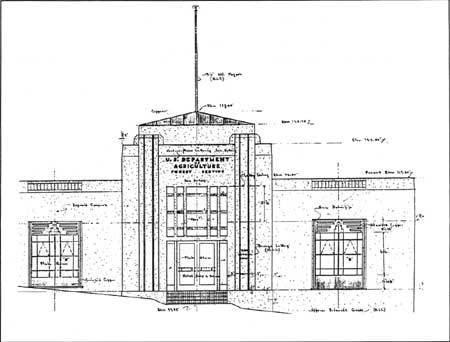

Between 1937 and 1942, the San Francisco design office produced many modifications to the Blanchard and Maher designs as well as new designs for site-specific buildings. One unique design for a supervisor's office in Nevada City had an Art Deco feeling (figure 3-9). Other designs of the period included adobe buildings for a research station just north of Fresno and office and laboratory buildings with a New England character at the Institute of Forest Genetics in Placerville. The CCC program started to decline in 1940 as the war in Europe escalated, and by 1942 no more new construction projects were begun.

|

| Figure 3-9. Design for Tahoe National Forest Supervisor's Office, Region 5 (c. 1937-42) |

In early 1942, Jim Byrne, the Forest Service Regional Engineer in San Francisco, was called by Major Evan Kelley, then Regional Forester in Region 1, to be the head engineer for the guayule rubber project (see page 44). The project headquarters was set up in Salinas, California. Clyde Fickes, Regional Architect from Region 1, was the head of the construction team. Keplar was one of four Forest Service architects called to assist the project in providing the buildings needed for this important war effort. The war in the Pacific ended in August 1945, and the guayule project was abandoned later in that year.

When Johnson returned to San Francisco, he found he had a new supervisor. William Minaker, the Forest Service bridge engineer, had been promoted to Assistant Regional Engineer. Johnson returned to an empty office in the Ferry Building. There were very few construction dollars. His draftsmen had left before the war, and the major emphasis was on reopening buildings and stations that had been closed by the war and maintenance of the buildings that had not had much care during that period. It was not until the early 1950's that things started to change.

Just prior to the attack at Pearl Harbor, the Government had started construction of a new Federal Building near the financial district in San Francisco. Because of the war, all activity ceased and the steel skeleton had stood rusting in the weather. After the war ended, the building was completed and the Forest Service Regional Office was to move there in mid-1946. Johnson was given the task to lay out the space for the employees. He hired a draftsperson, Lydia Thurnburg, to assist. Between them, they interviewed the employees and worked with GSA to prepare for the five-block move.

In early 1950, two new programs came to the California Region. First, the Army Corps of Engineers began to build new reservoirs in central and southern California. Second, a watershed protection and restoration program in the Los Angeles Basin and the Santa Barbara area provided dollars to the Forest Service to build new fire stations. Special funding was also allocated for construction of employee dwellings, barracks, dormitories, and mess halls. The staff of two was no longer able to keep up with the workload. Johnson hired another draftsperson, Beatrice Hadsell, and eventually two young architectural students, Joe Lazaro and Douglas Rodgers. Johnson, being the only registered architect in the office, oversaw all of the design work.

Johnson's designs started taking on a new character because of the southern California semi-desert environment. He started using concrete blocks, flat roofs with large overhangs, and metal windows. These new designs contrasted greatly with the Blanchard and Meher California Ranch theme and his own early 1940 experiments. One reason for the change was economic: there was a dollar limit on buildings set by Congress in a reaction to some Department of Defense construction projects after the war.

Perhaps the most notable of Johnson's work was the design for the new supervisor's office for the Tahoe National Forest, which was completed in November 1945 but never constructed (figure 3-9). In any case, Johnson's designs for the Region's buildings in the period from 1940 to 1960 showed a much greater range in terms of style and material than those of the 1930's. This is in part a result of Johnson being charged primarily with designing site-specific structures as opposed to the mass-produced buildings of the 1930's. It may also be seen as a reflection of the dramatic change in postwar American architecture.

By the middle 1950's, Congress started appropriating funds for new construction over and above the two special programs mentioned above. New buildings were needed on the northern California forests for both management of the land—with a particular emphasis on timber production and harvest for the residential construction of the postwar period—and for recreation use. Johnson realized that he needed additional professional assistance in design and field construction engineering. He advertised for a graduate architect, interviewed several, and selected Harry Kevich as his second in command in 1958.

After Kevich's arrival, Johnson took on two tasks as his personal duties. He did all of the structural design for the buildings designed in the office. As the only registered architect in the office, he checked and signed each drawing. Webb Kennedy had followed Jim Byrne as Regional Engineer and was providing leadership to the Region as it entered a new era of engineering activities.

The Regional Office was growing, and there was not enough space in the new Federal Building on Sansome Street for all the employees. The architectural and bridge sections moved to an office on Market Street. This translated to more space planning for Johnson and constant travel to Sansome Street for meetings. Two more employees joined the architectural staff: Bill Peterson came as a student trainee and John Grosvenor replaced Lydia Thurnburg as a draftsperson. As the timber program increased, so did the need for new buildings, both offices and barracks, as well as many new recreation structures.

Another new project that came up was a new fire air attack base in Redding, California. Two of the major structures, an auto shop and fire cache, were given to a private architectural-engineering firm in Redding. All of the other buildings were to be designed in house. Johnson took charge of moving a large surplus airplane hangar from Hanford, California, to the Redding site. He and Joe Lazaro traveled south to look at and measure the building. The local forest engineering office in Redding worked on the master site plan. Other buildings that were designed for the project included barracks, a messhall, and family residences. This project took most of the office's time for 6 months to complete the architectural contract drawings.

With the conclusion of these new major designs, Johnson started thinking about retiring. He left the Forest Service in 1962.

Arthur F. Anderson

Harry W. Coughlan

Regional Architects, Region 1 (c.1931-1935 and 1956-1978)

by Arthur F. Anderson

I was born in western Montana. Growing up, I came to realize that this was exactly where I wanted to live—in the mountains with their lakes, rivers, forests, and all the creatures sharing that environment. To earn money for college, I found work on summer fire crews. One fire camp operated from a former CCC camp near the Northern Region (Region 1) Remount Depot. In 1941, I started architectural engineering studies at Montana State University in Bozeman. Then World War II erupted. I qualified for a Navy officer training program that took me to the University of Michigan. That program allowed students to continue their education along with Navy training. Following a brief tour with the Navy, I was able to return to Michigan, getting my bachelor's degree in 1949.

Degree in hand, I began working for an architectural firm in my hometown of Kalispell, Montana. With my wife, I began trekking around the State as onsite representative for the firm. The work was on schools, elementary through college. Structures included steel, reinforced concrete, brick, tile, wood frame, and laminated wood. Water systems, plumbing, waste disposal, heating systems, intercoms, and electrical work were all parts of each project. Here I learned about contract construction: drawings, specifications, getting bids, making awards of contracts, and dealing with primary and sub-contractors to get work done in accord with bidding documents.

Projects took me from one Montana town to another until we landed in Missoula. Here I ran a branch office for the Kalispell firm along with overseeing their work for the University of Montana. By this time we had two children with another on the way and were thinking of finding a way to stay put for a while. In the spring of 1956 I passed the exams to become a licensed architect in Montana. Missoula looked good. I became acquainted with other architects and engineers around town, including Harry Coughlan, architect for Region 1. Going into the winter of 1956, it appeared we might have to close the Missoula branch office. Harry had an opening for a GS-9 architect. I decided to apply for that position and see what might happen. Just before Christmas, I learned the Region 1 job was mine if I wanted it. So began my Forest Service career with a really fine gentleman, Harry Coughlan, as my boss.

Harry Coughlan was born in St. Joseph, Missouri, in 1905—the same year the Forest Service became an agency with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Somehow he found his way to the Northwest, went to schools in Idaho, and got a degree in architecture from the University of Idaho in 1929. In the Depression year of 1931, Harry got a job with the Forest Service, got married, and moved to Missoula—though not necessarily in that order.

About the time I began working with Harry Coughlan, there were some 100 or more new recruits coming on board for various jobs on ranger districts, at supervisors' offices, and in the Regional Office. We even had a new lawyer for the Office of the General Counsel and a few Research people. We all attended an orientation session at the Missoula Aerial Fire Depot (the smokejumper center), which had been designed by Region 1 architects and engineers, completed in 1954, and dedicated by President Eisenhower before a crowd of some 30,000 people. Here we learned who was running what in the Forest Service generally and in Region 1 particularly. We learned what was expected of us and who would be our coworkers and clients. Opportunities, needs, money sources (and problems), and other restrictions were brought up. Longlasting friendships began. If I had to look for a negative aspect of this initial meeting, it would be learning that construction contracts were not administered by the designing architects and engineers but by contracting officers who seemed to have a wide variety of backgrounds and concepts of their authority.

Further orientation to the work of Forest Service architects and engineers came from Service-wide meetings. The Forest Products Laboratory in Madison hosted one of these sessions. We learned to use the Lab to get information on the characteristics and proper usage of wood and many other materials. Buckminster Fuller, seer of the future and creator of geodesic domes, talked to us at one Service-wide meeting. Another speaker asked a thought-provoking question: "Is there a substitute for imitation wood?"

Harry Coughlan did a great job of exposing me to the history and tradition of the Forest Service and the Northern Region. There is a log cabin at Alta on the Bitterroot National Forest that was built in 1899 by H.C. Tuttle and Than Wilkerson (see figure 1-1 on page 3). It is now on the National Register of Historic Places as the first U.S. forest ranger station. This station was built for the forest reserves; the Forest Service took over in 1905.

Region 1 has a rich legacy from the CCC days, 1933 to around 1942, when hundreds of unemployed young men learned how to build. They built recreation improvements, fences, roads, trails, telephone lines, lookouts, and other buildings—at their own camps and at some ranger stations. They were under Army supervision for pay and sustenance but under other agencies for many of their work assignments. One huge CCC job, instigated by Regional Forester Evan Kelly, a former U.S. Cavalry Officer, was the Remount Depot, where the Forest Service bred, fed, and trained horses and mules for riding and pack stock. The buildings were designed in Cape Cod style (see figures 1-12 and 1-13 on page 16). Fenn Ranger Station, on the Nezperce National Forest in Idaho (see figure 1-27 on page 35) and Phillipsburg Ranger Station, on the Deerlodge National Forest in Montana (see figure 2-44 on page 83) are other examples of CCC construction in Region 1. All of these facilities are on the National Register of Historic Places. Architect Bill Fox and engineer Clyde Fickes designed the buildings and grounds and guided construction. Fickes was the boss. Harry Coughlan worked with them.

During World War II, Fickes and Coughlan worked in California on the guayule rubber project along with many other Forest Service architects and engineers. When the rubber project ended, Fickes left Region 1. Bill Fox went into private architectural practice. Harry Coughlan stayed with Region 1. He joined the circle of Regional Architects that included Keplar Johnson of Region 5 and Nels Orne of Region 9. Their Washington Office direction came mainly from Tony Dean. Tony seemed to know everything that was going on in all of the Regions and Research Stations all of the time—a most competent, levelheaded, fatherly but no-nonsense engineer.

The "custodial" period for the Forest Service ended as people recovered from World War II and literally swarmed into their woods for recreation and jobs; making use of the resources. We quickly developed "standard" designs for every kind of building needed by district rangers to keep up with pressure from forest users. We had office-warehouses, garage-shops, barracks, cookhouses, lookouts, outhouses, and several kinds of dwellings. Seldom did a "standard" plan fit a given situation without modification. We tried to keep everybody happy and largely succeeded.

One thing that particularly tested our ingenuity was trying to meet limitations placed on dwelling size and cost by the Appropriations Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives. We couldn't exceed 1,200 square feet nor the year's assigned cost limit, guidelines probably reasonable for typical urban situations where there were skilled builders and it wasn't a 2- to 4-hour trip from a ready-mix concrete plant to the building site. Legislative limitations often forced us to do things like leave out basements and scrimp on residents' storage and dining space, which made life tough for housekeepers in the backwoods.

Harry and I needed help and we got some good people from colleges and the private sector. Some of our projects involved contracting with private architects and engineers. We helped Research with their nurseries, research centers, and a fire laboratory. We helped Information and Education with visitor and interpretive centers. We designed restrooms, pumphouses, and related items for recreation sites. We got into design and analysis of fallout shelters. We did Job Corps Centers. In one instance we got a standard plan for a Job Corps Center gym. It was a bit light in the roof snow load design for our Region and we told the Chiefs Office our problem. We got back the terse advice: "Do not make modifications; have the enrollees shovel the snow if it gets too deep."

Speaking of shovels, the primary summer and fall job for nearly every able body in Region 1 was fire—on one or at a staging area where firefighters passed from one fire to another. Given the short building season in the Northern Region, this complicated getting building projects designed and built in many tough fire years.

Two of our Job Corps Centers were housed in buildings we remodeled at radar bases no longer in use. For another one, we contracted for design and installation of prefabricated structures, which were hauled to the site in the same manner as house trailers and then linked together. Sometime after this center closed, we learned that most of the structures had been moved to a summer work center way out in the boondocks, where they were eventually flattened by heavy snow during the off-season.

Prefabricated structures and house trailers often provided quick and easy solutions to building needs. They could be acquired with year-end money and without need for a design. They were obtained as personal property so they didn't appear on fire, administrative, and other building inventories. These kinds of improvements often showed up only when we were called on to help design shelters or storage structures to make up for their deficiencies.

The Bureau of Reclamation made some of their buildings and sites available to other agencies as dams were finished. We in Region 1 could hardly afford to turn them down and so began a parade of mostly dwellings over the highways and backwoods tracks of the Region. At Hungry Horse Dam on the Flathead National Forest, a district took over the whole spread from the Bureau. In another case, administrators of a forest decided to move an office building from a dam site to a remote work center. The building had to be cut into sections for moving. One of the pieces went into a Wild and Scenic River as the mover came around a tight corner in the road. Very quickly a lot of folks got together about the situation. It was some time before the whole office got to the work center. Here again, we often didn't have enough funds to afford basements. However, later on, possibly justified as fallout shelters or by other logic, a few basements were added. Someone remarked, "Well, that way we sure found out where the basement had to go."

With passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964, the Forest Service launched a determined effort to acquire private land and remove all structures from established wilderness areas. This required owners of such properties to come to the bargaining table. I had attended a 2-week session on real estate appraisal in 1963. That course led me to a most interesting and sort of poignant assignment: determining the value of improvements at a wilderness ranch on a national forest. The ranch was originally homesteaded from 1911 to 1947. In 1947 it began to be used mainly for recreation. A landing strip was built. A diversion dam on a nearby stream provided hydraulic power for a generator. A sawmill was installed. Soon there were guest facilities for quite a sizeable party. Up to 1961, improvements were still being added. An appraiser from Recreation and Lands and I headed for the ranch in December 1965. My job was to assign a value to the buildings and related improvements, his was to nail down what the land was worth. We were flown in to a remote Forest Service ranger station landing field. Here we loaded up with food and other gear for a few days' stay at the ranch. We hiked a few miles to the site. The owners were just leaving and showed us around. Hunting season was over, but fortunately the winter had not yet set in on that neck of the woods. As we went about our work and did necessary chores for our meals and night's comfort, we were deeply impressed with the tranquility of the place. We watched elk feed on the hillside off a hundred yards or so. It was a privilege to be there, but it was a place that only a few very wealthy people would be able to visit and enjoy as it existed. Eventually, the Forest Service did acquire that ranch and I suppose it has reverted to a wilderness character, albeit somewhat less than pristine. In other cases, the Forest Service has not succeeded in ousting landowners from wilderness sites, but the efforts go on.

While Harry and I managed to recruit graduate architects, we ran into a brick wall when these fellows tried to qualify for architectural registration. The National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) refused to credit more than 2 years of work for any Government agency toward the required 3 years of work under licensed architects practicing as principal of a business. Both Harry and I were licensed and so were some others working with us. Our Regional Engineer, Max Peterson (later Chief of the Forest Service), challenged the NCARB head office about it—to no avail. Some of our college recruits left to work with private firms. Somehow, Bob LeCain was an exception and got his license while working for us. It is my opinion that the usage of contracting officers by Government agencies lends support to the hard-nosed NCARB position. Contracting officers take on much of the interaction with contractors normally recognized as a legal responsibility under private architects and engineers. Thus that part of architectural practice would be unfamiliar ground to one who left a Government agency to become a private practitioner.

Specifications for construction projects were another part of our work that we tried to standardize. I joined the Construction Specifications Institute. We found their format very helpful. We sent copies to the Washington Office, but there was no immediate response. At a Service-wide meeting of architects and contracting people, I brought copies of the format for each Region, and comments were mostly positive. Eventually, the Washington Office got into gear, and standardized formats were adopted in 1967. I think a Washington Office administrator got an award for getting this done.

Harry Coughlan retired in the fall of 1965. He did some outstanding water color painting after retiring. Most of these grace walls in homes of his immediate family, but there are also a few in the square dance halls where Harry and his wife Doris spent many hours. Harry died in 1982 at the age of 77.

I replaced Harry Coughlan in 1966. I retired in 1978. Before I retired, I took business management courses at the University of Montana. After several years of part-time classes, I earned a master's degree in business administration (MBA). That really didn't impress any of my coworkers too much, nor did it lead to higher pay. But it gave me a good perspective of management. It didn't take much insight to see how a lean and effective outfit could drift into a condition where it was top-heavy in executives and ineffective in operation. Corporations and agencies alike seemed to go that way from 1960 to 1990. Then along came downsizing, where both good and bad things have happened.

The Forest Service began the Roadless Area Review and Evaluation process, called RARE, in the 1970's. It is still going on, due to lack of final congressional action needed to put it to rest. In 1972 and 1973, I was detailed to the regional task force on RARE. At first we spent a lot of time getting map data from forests as they located, defined, and refined areas that fit the roadless criteria. During this period we helped whoever wanted it to have access to RARE information at whatever time was convenient to them. For many people, RARE involved a lot of overtime and stressful activity. It was a good experience for me, rubbing shoulders with foresters, ecologists, and wildlife specialists as well as politicians and environmentalists. I got a fresh appreciation for our national wilderness heritage.

From the Forest Service, my wife and I embarked on a 2-year tour with the Peace Corps. Our assignment was to an island in the Caribbean. Paradise, right? Well, if Paradise includes living through overthrow of the Government for a few months, OK. But hurricanes? One each year like the island had not had for 50 years? During the first one I watched in awe as 4- x 32-inch pieces of glass in a jalousie-type window bowed in nearly 3 inches from wind pressure before snapping. Then the roof blew off over our heads in one flying piece. Luckily, we weren't hurt, but we sure got drenched before we got to other shelter. Both years the banana crop was ruined, so there went the economy. Instead of working to maintain and improve the island's school facilities, my original task, I ended up assisting a very competent Caribbean engineering firm in the design of buildings to replace some that had been wiped out by the hurricanes. The Peace Corps was a fine experience. We learned more than we taught and got more than we gave.

Now here I am, exactly where I always wanted to live—in the mountains with their lakes, rivers, and forests and all the creatures sharing that environment. Lately, more of the creatures are human.

A.P. "Benny" DiBenedetto, FAIA

Regional Architect, Region 6 (1951-1961)

Station Architect, Pacific Northwest (1961-1979)

Washington Office Research Architect (1977-1979)

I was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1922. I attended school in Portland, at Benson Polytechnic High School, where I majored in architecture and building construction, graduating in 1940. In the fall of 1940, I accepted a scholarship to the University of Oregon's School of Architecture. (DiBenedetto's father, Jack, who emigrated from Italy in 1906, was a stone mason hired to work at Timberline Lodge. His father taught his son the craft before sending him off to college to learn architecture.] During the summers of 1941 and 1942, I worked as an architectural draftsman for the Corps of Engineers, working on Army and Air Force bases in the Northwest.

In early 1943, I joined the Navy and served in the South Pacific and Middle East. After the war, I returned to the University of Oregon to complete my degree in architecture in 1947. Upon completing my college degree, I returned to the Corps of Engineers, working on fish hatcheries and the powerhouse and observation building on the Detroit Dam.

In early December 1950, I was interviewed by Mr. Frankland, Regional Engineer, and Tim Turner, Regional Architect, to assist Mr. Turner in the design of new ranger stations at Detroit, Oregon, and Lowell, Oregon. I was to start work in February 1951. Two weeks after our interview, Mr. Turner had a heart attack and passed away. Jim Frankland called me on January 3, 1951, and asked if I could come to work in 2 weeks. I said I could because I was just finishing up the observation building at the Detroit Dam.

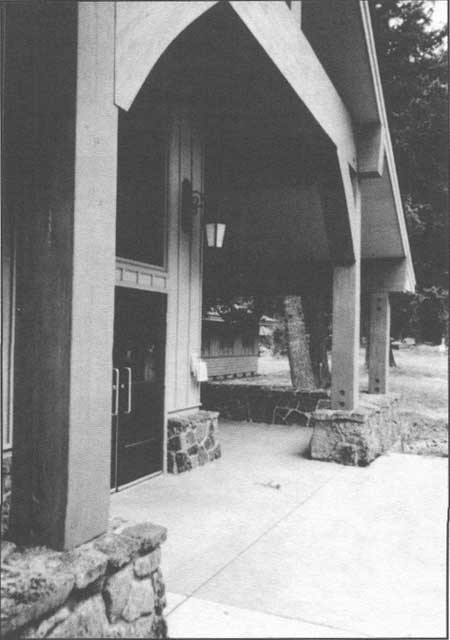

From February 1951 to 1961, I worked with the following architects: Bill Hummel, Dick Parker, Ken Grimes, Doug Parmenter, and Norm Krause. We designed and built new ranger stations at Detroit and Lowell, Oregon, and ski chalets at Mt. Baker and Mt. Bachelor, Oregon; and we did the first restoration of Timberline Lodge in 1955. Later, Joe Mastrandrea, Perry Carter, Ken Reynolds, Terry Young, and Tom Morland joined our staff. In 1958, we continued doing administration facilities; nursery buildings at Wind River, Bend, and Medford, Oregon; and the first Olympia Laboratory.

In the summer of 1951, Ellis Groben came to Region 6 for a week to visit and review his design philosophy for the Forest Service. He was impressed with the Northwest Cascadian style of architecture that was started by Tim Turner, Linn Forrest, Dean Wright, and Howard Gifford on Timberline Lodge and numerous CCC facilities in the Washington and Oregon area. I recall one day when Groben and I were walking in town, he would cross a street diagonally without looking and with no sense of auto traffic, causing automobiles to honk their horns frantically. I found him to be a little eccentric.

In 1961, I transferred to the Pacific Northwest Experiment Station as the Station Architect and architect of record for the design and construction of research laboratories at Corvallis, Oregon (1962); the second Olympia Lab (1964); Wenatchee, Washington (1965); Roseburg, Oregon (1966); and La Grande, Oregon (1970).

Our architectural staff designed research facilities at Rhinelander, Wisconsin; Duluth, Minnesota; Fresno, California; St. Paul, Minnesota; Moscow, Idaho; and Botteneau, North Dakota. The Forestry Sciences Laboratory in Corvallis, Oregon, was designed in three phases: the first in 1962, the second in 1968, and the third in 1973. In order to design research facilities nationwide, I had to maintain architectural registration in Oregon, Washington, California, Idaho, Montana, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Iowa.

Our design team received awards for laboratories at Corvallis and Bend, Oregon, and the laboratory of the year award for the Range and Wildlife Laboratory in La Grande, Oregon, in 1973 (below). In 1973, I was elected to be president for the Oregon Council of Architects; in 1974 I was elected as Director of the Pacific and Northwest Region of the American Institute of Architects (ALA) and served on the National Board of AIA. I served in this capacity until 1977. In 1978, I was elected to the College of Fellows for the design of the research laboratories and service to the Institute.

From 1977 to 1979, I served as dual Station Architect and Washington Office Architect for Research. After I retired in 1979, I was asked to be a consultant on the restoration of the Auditor's Building (originally built in 1869) for the Forest Service national headquarters and for a proposed new laboratory for Hawaii, which I did from 1987 to 1989 as a Forest Service volunteer.

|

| Figure 3-10. Range and Wildlife Habitat Laboratory, LaGrande, Oregon—1973 Industrial Research Laboratory of the Year design award winner |

The staff architects doing research facilities nationwide were Dick Lundy, Fred Wagoner, Tom Morland, Si Stanich, Dale Farr, Albert Biggerstaff, Bill Headley, Mari Ellingston, Dan Wrigle, Alton Hooten, Bill Hohnstein, Mike Madias, and Joe Mastrandrea, who have since gone into private practice or retired.

Since retiring from the Forest Service in 1979, I have maintained an active practice in architecture, doing visitor centers and housing and historical restoration at Crater Lake National Park, Nezperce National Monument, and Fort Clatsop. With our firm of DiBenedetto/Thompson, we have designed a campus complex for Soloflex in Hillsboro, Oregon. In 1985, we did a large Bio-Tech Laboratory for Pioneer Hi-Bred in Johnston, Iowa, and Portland, Oregon. We have been deeply involved in restoration of Catholic churches at Mt. Angel, Oregon, the first Catholic church in the Northwest Territory, built in 1846, and a 14-unit housing complex for retired clergy.

My career as an architect for the Forest Service was very fruitful and rewarding. The group of architects working with me came from many schools of architecture and appreciated the opportunity to be designing structures in the natural environment. In two instances I was asked to move to Washington, DC, as Forest Service Architect. That is the reason I transferred to Research and subsequently it became a dual assignment in my later career with my office in Portland.

(In a 1989 article in the Daily Journal of Commerce, DiBenedetto was described as the "Italian Godfather," a mentor to many top Oregon architects. This nickname was bestowed on him by numerous young architects he had trained over the past 40 years. Benny always had a clever comment and positive criticism; "An architect could not be a better godfather," said Portland architect Dale Farr. DiBenedetto directed many of his students at the Forest Service office, designing ranger stations and research labs. More recent apprentices have been trained in his Portland private practice. "I still enjoy having young people around," explained DiBenedetto during a recent interview. "It gives me a lift as to what changes the design profession is going through. I still haven't been able to absorb post-modernism," he said.]

I am indebted to Tony Dean and Jim Bryne, Chiefs of Engineering; Dr. George Jamison, Chief of Research; Directors Robert Cowlin, Phil Briegieb, Robert Harris, Robert Callaham, Robert Buchman, and Robert Tarrant; and Administrators Charles Petersen, Jim Sowder, and Sam Kessler for the opportunity to design research facilities to fulfill the needs of the Forest Service's research nationwide.

— Benny" DiBenedetto (1997)

William Turner

Regional Architect, Region 4 (1956-1981)

I was born in Provo, Utah, in 1918. I spent my summers in Heber City, Utah, with my grandparents, where I learned to work and take responsibility and also got acquainted with rural life.

During my senior year at Provo High School, I was busy for a few days deciding what vocation to pursue. I was torn between forestry and engineering. I loved the mountains and outdoors so much that I thought about forestry, but finally decided on civil engineering because of my great love for math and science and building work. I studied 2 years at Brigham Young University in Provo, but then had to transfer to Utah University because that was all they offered in engineering then. I finished my studies and graduated with a B.E. in civil engineering in 1941.

After graduation, I was hired by Columbia Steel and sent to work in Torrance, California, just south of Los Angeles and later transferred to Provo. When the new Geneva Steel Works opened, I went to work for them and stayed until they closed the plant at the end of the war in 1945. I then went to work for the Bureau of Reclamation in Grand Junction, Colorado. I had heard about Colorado's mountains and fishing and wanted a taste of them myself. After 11 months, I was transferred back to Spanish Forks, Utah.

I left the Bureau of Reclamation and went to work for the city of Provo, helping to build a large addition to the city powerplant. Next, I worked for a combined lumber yard, cabinet shop, ready-mix concrete, and home building company in Pleasant Grove, Utah. When the need for new housing lessened, I went to work at the Army Desert Chemical Depot southwest of Toole, Utah, and stayed for about 3 years. That was a good all-around engineering job.

When that job finished, I went to work at Hill Field, just outside Ogden. After 2 years, I learned that the Forest Service employed engineers. I inquired at the Regional Office Division of Engineering, but they didn't have anything to offer at that time. Nearly a year later, I went back again and took a set of house plans that I had prepared. I was told that the regional architectural engineer was retiring and was asked if I would like that job. I readily accepted it, even though it meant a reduction in grade and pay.

I just thoroughly enjoyed my work. The Forest Service is a good outfit; there is such a good feeling among the employees, almost like a family—as it was often called. This combined my two interests: forestry and engineering. I got outdoors in beautiful country. George Nichols, my predecessor, had left before I was hired, although I did consult with him quite often. He surely produced a lot of plans for many different kinds of buildings which were built during his tenure.

I started the job there in July 1956. The architectural staff at that time was Cal Spaun. He was a splendid and talented architectural draftsman. He had worked for a prominent local architect named McClenahan, who designed the Regional Office in Ogden as well as the City and County Building and the high school. I remember that Ogden High School had been built during the 1930's at a cost of approximately $1 million. It was unimaginable back then for anything to cost a million dollars.

When I started, the Division of Operations controlled the building program money and therefore the building program, so I was somewhat under the supervision of Tom Van Meter and his assistant Tom Matthews. Van, as he was called, was very talented. He liked to be in the middle of everything and often liked to stir up a fuss. There was never a dull moment when Van was around.

When I started, we were way behind and I had to work evenings and weekends to catch up. Tom Matthews was in charge and informed me that in addition to plans and specs for a new dwelling, they wanted a complete list of materials—the contract would be for labor only, the Forest Service would furnish the materials. That caused a lot of discussion, but he was insistent, so I went ahead with it—a big job to determine all the lumber, nails, plumbing, heating, electrical, and other supplies to construct the dwelling. However, just before I finished it, he informed me that they wouldn't need it; they would let the contract for labor and materials after all. Thank goodness!

We were constructing mostly dwellings when I started. We had some garages and some campground latrines. We did have a few office buildings. During the mid-1960's, we received quite a bit of money with fiscal year deadlines from Congress for the accelerated public works program, and we had so much work that we let some of our architectural work out to private firms, mainly to revise some of our plans to better fit the sites where they were to be built. I remember making an inspection on the Bear River Office, up in the mountains, while it was under construction. The building was almost completely framed; I got to looking at it and realized something was wrong. The roof structure was not strong enough for the local conditions. The designers had not taken that into account, and we had not caught it during our brief review of the plans. We had to get busy and make changes in order to strengthen the roof.

Another thing that comes to mind. We have a lot of summer homes in the Region. One time a couple of the permittees out of Logan, Utah, had purchased summer home plans from a private firm and the Forest Service had turned them down for construction because the designs were not strong enough for the area. The national sales manager for the company called me to find out what the problem was. I told them that the design for the snow load was too light. He said, "They are designed for 50 pounds!" I said that is about the minimum we use, design another for 100 pounds, and another for 150 pounds, and sell the one they need. He said, "Oh no, that would cost more money and be hard to sell."

We sent him a letter explaining the Forest Service policy: we review the plans to see that they are both aesthetically right and physically strong enough for the particular site; that we use snow and water content records compiled by the Soil Conservation Service to determine the snow load requirement for a particular site; that 100 and 150 pounds are common for our Region. We then listed the Soil Conservation Service records that covered our Region. That didn't phase him. He even came to visit me and brought another dealer from Logan. He wanted blanket approval to build their 50-pound buildings anywhere. He even went to the Washington Office to see if he could convince them. We sent the Washington Office a copy of the letter we had sent him and said, "He knows our requirements, but seems to be interested in nothing but the sale price." We never heard any more about it.

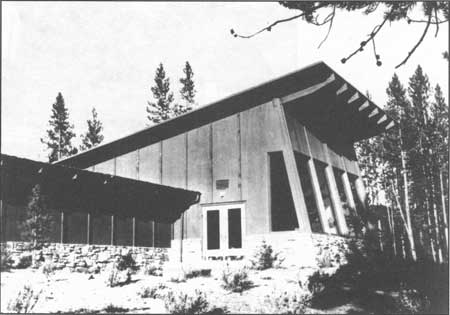

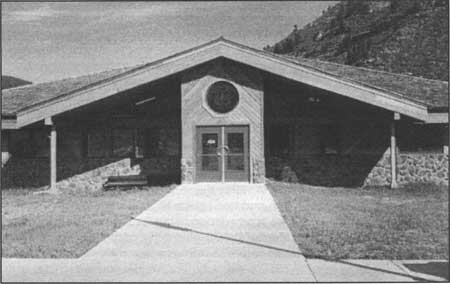

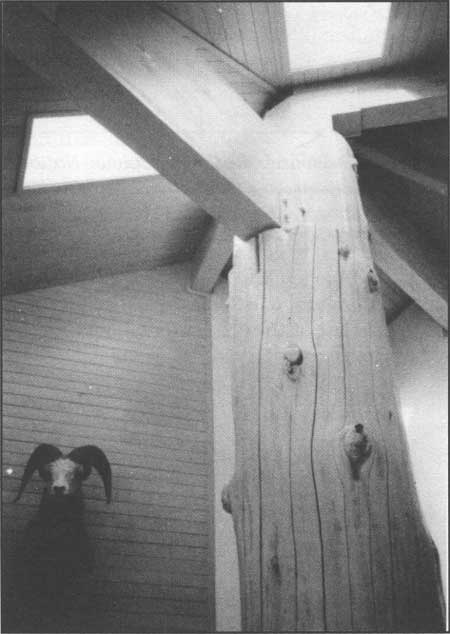

One special building I remember was the visitor center at Redfish Lake on the Sawtooth National Forest in Idaho (figure 3-11). A helper at that time was Darwin Hamilton, who was quite artistic; he came up with the basic looks of the building and I did the structural design. That is a beautiful site and we built this great building there. It was very enjoyable. Soil Conservation Service records showed that 70 pounds should suffice. However, because of the much heavier snow loads close by, I did not want to take a chance and designed it for 100 pounds. I was fond of heavy shake shingles and put them on the roof. The pitch of the roof is borderline, and we eventually put sheet metal on the overhang edges to control the ice dams.

|

| Figure 3-11. Redfish Lake Visitor Center, Region 4, central Idaho (1964) |

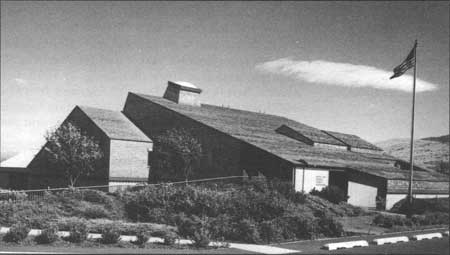

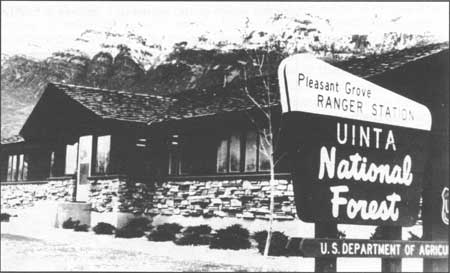

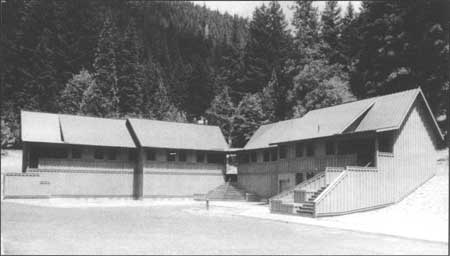

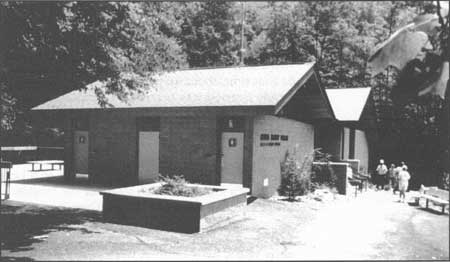

One of the struggles I had earlier in my career was dealing with the Division of Operations. They were very strict with the building budget and did not want any "frills" on the buildings. For example, we could not put trim around porch posts, adjustable shelves in utility closets, wood shakes on roofs, or stone on the exterior of buildings. It took me a while to get them to understand that these items would improve the buildings and last longer. The Pleasant Grove District Office on the Uinta National Forest (figure 3-12) was one example of an office designed after convincing the building committee that adding a little to the offices was wise.

|

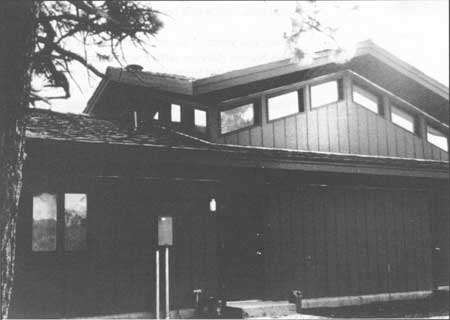

| Figure 3-12. Pleasant Grove District Office, Uinta National Forest, Region 4 (1963) |

I also enjoyed designing some of the other offices. My favorite design is that of the Ketcham (Sun Valley) District Office on the Sawtooth National Forest. It was designed to appear as if coming up from a rock outcrop just in front of it.

I remember some interesting experiences, such as going up to Big Piney, Wyoming, to see about remodeling the heating system in the District Ranger Office. The ranger there told me that he had seen it 60 degrees below during his stay there. Another time there was a Boy Scouts of America lodge that was to be built under a special use permit on the Caribou National Forest near the Palisades Dam on the Snake River. I had reviewed the plans and approved them, including the roof trusses that were to be built using "split rings." While inspecting some buildings we were having constructed in the vicinity, the Forest Supervisor asked me to take a look at the Scout building. It was all framed and enclosed. When I inquired about the split rings, the builders seemed puzzled. Further inquiries disclosed that they didn't know what split rings were, and had inserted flat washers in the truss joints instead of the split rings. We had to get busy and strengthen the roof to prevent its collapse.

We planned and built quite a few diversified buildings: warehouses, a nursery building complex near Utah State University in Logan, and a tree nursery complex at the Lucky Peak site near Boise, Idaho. Two special buildings were required there. One was a tree cold storage building where trees would be stored after being taken from the ground in early spring for sorting and packaging. The building was to be designed for a temperature of 34 degrees Fahrenheit and 100 percent humidity! We hit it pretty close. A second was a seed cold storage building, which was to be designed for zero degrees Fahrenheit year round. After it was built, I was there in August. The temperature outside was over 100, and inside it was minus 8 degrees—quite a difference. Another interesting building is the Stanley Ranger District Office on the Sawtooth National Forest, not far from the Redfish Lake Visitor Center. It is a rustic, early-day type of building with a covered front porch and a main entryway and reception room, with a wing to be built on each side of it. The south wing was designed and built originally; the north wing has not been built.

I had two very fine helpers during my tenure: Al Saunders, who had considerable experience drawing Forest Service maps, and Wilden Moffett, a graduate architect, who is my successor as the Regional Architect.

I would like to be remembered as a good friend and a helper of the Forest Service. I came to do a job and enjoyed the work and the people. It's good to see the results of my efforts. I think this is a great outfit—one of the best!

—Excerpts from interview done by John Grosvenor in May 1998.

Harry Kevich

Regional Architect, Region 5 (1958-1985)

I was born in San Francisco in 1926. I attended public school in the City; after graduation, I was drafted into the Army and served for 2 years (during the Second World War). After I was discharged and returned to San Francisco, I was accepted at Stanford University, which I attended for 4 years. After receiving my bachelor's degree in architecture, I went to Harvard Graduate School of Design.

I then worked for private industry for 3 years. I terminated with the firm to attend the World's Fair in Brussels, Belgium, in 1958. I came back to the Bay Area without a job. I had just purchased a lot at Squaw Valley, where I planned to construct a wood cabin to be used by me for the 1960 Winter Olympics and needed some timber design experience (my work experience in private industry had been mostly in steel and concrete). As I was driving back down old Highway 40, I saw the Big Bend Ranger Station of the Forest Service and wondered if they had a design department.

The next day I phoned the Regional Headquarters in San Francisco and spoke to the Personnel Department. I asked if they had an architectural staff to design their buildings and if they ever had job openings. Their answer was yes and that there was an opening at present. I was given the Regional Architect's name and phone number. The very next day I went into the office on Sansome Street to have an interview with Keplar Johnson. We spoke for about 2 hours, going over the scope of the work in the office and my qualifications. Kep offered me the job then and there; I accepted, and that started my Forest Service career. I never thought it would last 27 years.

In thinking about my career during the years I was Keplar Johnson's assistant, working with the forest personnel was a good experience. But, after Kep retired and I became Regional Architect, the best times started. I realized I was getting a lot of support from the forest supervisors and engineers. They were aware we were capable of doing the projects and they were anxious to receive this product. By the same token our work increased with the demands, which was very gratifying. This allowed us to increase our staff and gave us the opportunity to select what I think were very talented people. And it created a stimulating environment for all of us in which to produce exciting architecture in the Region. And in the same way this was also reflected in the field, with a lot of encouragement and support from the forest personnel with their interaction in the design of buildings—which was challenging and called upon our creative energies to do the best architecture possible.

The bad times were the years when Charlie Connaughton was Regional Forester; he posed a great many restrictions, as I remember. For instance, he insisted we provide asbestos siding on buildings, which we now know has a dangerous history, rather than forest products, which were our preference. It was at this level that we didn't get sufficient support.

After Charlie Connaughton's departure, new management gave us support and recognition (specifically Jack Deinema and Doug Leisz), and this was super for our efforts. It was at this time that we started to get some national recognition of our capabilities and began performing work beyond our Region because we had the talent and capabilities to do it. We started to train young architects from other Regions where there were no mentors.

There was the time when Jim Byrne, Director of Engineering in the Washington Office, offered me the position of Chief Architect in the Washington Office. I remember having a long conversation with Max Peterson, Region 5 Regional Engineer, regarding taking the position. I did give it considerable thought, but I wrote a negative response to Jim and thanked him very much. I did feel that as a professional, I did not know of a principal in any architectural organization, be it private or Government, where the head architect was separated from a functional office, which would have been the case had I gone back to Washington. Professionally, as an architect, I do not think it would have helped the organization to be so separated. It would have been a managerial position with serious restrictions. Maintaining direct interaction with other architects and keeping abreast of trends in the profession can only be done in a functioning office.

The California office did a lot of work nationally for the Forest Service, especially for those Regions that did not have an architectural staff. It was very flattering. I remember being on the commission doing the study of the Cradle of Forestry in North Carolina; that was a very interesting project and there was an excellent group of people to work with.