|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part One

EYE TO THE SKY, FOOT TO EARTH

Chapter One

Your Forest Land

In the administration of the forest reserves it must be clearly borne in mind that all land is to be devoted to its most productive use for the permanent good of the whole people, and not for the temporary benefit of individuals or companies. All the resources of forest reserves are for use, and this use must be brought about in a thoroughly prompt and business like manner, under such restrictions only as will insure the permanence of these resources. Where conflicting interests must be reconciled the question will always be decided from the standpoint of the greatest good for the greatest number in the long run.

James Wilson, Secretary of Agriculture, in a letter establishing policy, February 1, 1905.

THE NATIONAL FORESTS of the United States of America embrace 176 million acres. That is nearly one-tenth of all our land. This land belongs to the people. It is their vast estate, and the United States Forest Service is charged to administer all its resources and uses in such ways as will increase the wealth and happiness of the people not only during the present year and century but also for all time to come.

An acre of land is about the size of a football field—the gridiron, proper. Our total national population at present stands at around 130 million. So each citizen's share in our national forest land if you want to figure it that way comes to about an acre and one-third. An acre and one-third is about as big as a football field, entire, with room for side lines, a press stand, grandstands, and dressing quarters.

|

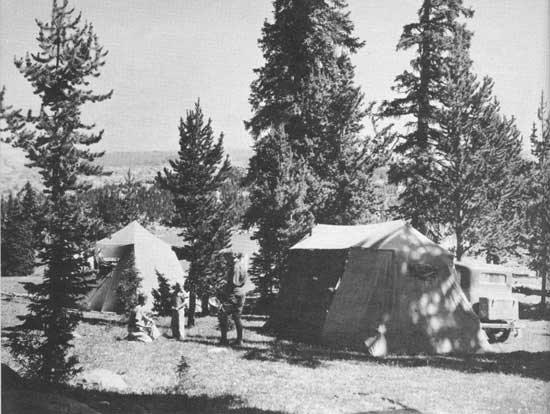

| What is it worth to this family to have a quiet road up the mountain and a place within easy-driving distance where they can take it easy? ISLAND LAKE CAMP, SHOSHONE NATIONAL FOREST, WYO. F-308555 |

To think of our national forests in terms of per capita shares or tracts, is invigorating; for all those many acres do, indeed, belong to all the people. "This land," as William Atherton DuPuy says in his book, The Nation's Forests (1938), "is ours though we live in a tenement and never see a chipmunk along a rotting log, or live on the prairie and never hear the wind sighing through the tall pine trees, or live on a water front where the odor of fish is more to be expected than that of honeysuckle. . . . Out there in the forest, along with the land belonging to the rest of the multitude, it is serving a very important purpose indeed. In fact, it is serving a number of purposes."

The national forests are the people's soil, and the crops are theirs. And it is no less stimulating to think of all this sparsely peopled land, the vast extent and stretch of 176 million acres, as a common heritage, not to be divided, pieced out in bits, but administered for the general benefit and pleasure.

This is the Forest Service's job, on 161 different national forests, no two alike. If all these forests could be grouped at our eastern coast, northward, they would cover all New England, plus all of the Middle Atlantic States, plus all of North Carolina, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Kentucky.

Actually, our national forests sprawl in scattered stretches from the palms of Puerto Rico to Alaskan spruce-hemlock, and lie within or across the borders of 36 different States, in the Territory of Alaska, and Puerto Rico.

IMMENSE AND VARIOUS, rich and poor, these sweeping Federal properties range from sea level to elevations exceeding 14,000 feet. They include all kinds of country and all kinds of cover. On some cut-over lands and on desert or near-desert stretches, charred stumps or grass, cactus or crouching shrubs are the only vegetation. Such country does not look like the general idea of a forest, but it all comes under that sweeping term, and is managed under long-run principles of restoration and use.

On greater areas the timber is of an infinite variety. The dense, dark fir-hemlock stands of the Pacific Northwest, the uniform open pine of the southeastern coastal plain, the varied, colorful mixed pine, fir, and cedar of the Sierras, the complex hardwoods of the Appalachians, the low chaparral of the Southwest, the towering redwoods of the California Coast, the juniper and piñon woodland of the Great Basin, the hardwood second growth of the Lake States, the oak-pine forests of the Ozarks—all these and other distinctive types of cover come within the scope of the term "forest." So, too, of the open parks within the spruce-lodgepole pine forest of the Rockies, the scattered stunted white-bark and foxtail pine of timber line in the Cascade and Sierra Ranges, the mountain meadows, the granite peaks rising like treeless islands set within the forest. The lakes and streams, too, are a part of the forest. Our national forests, then, are a kind of country of their own sort, greatly varied, but distinct from developed farm lands and from an urban environment.

This forest domain is managed under a highly decentralized administrative scheme, with national headquarters in the Department of Agriculture, in Washington. It is an over-all system of management with each forest officer, be he ranger, supervisor, or regional forester, singly responsible for a large stretch of public land. In this system the multiple-use principle of management is followed, each area producing timber, water, forage, wildlife, and other forest values, all at the same time, each resource being developed according to its relative importance. Only a small part of the national-forest area is devoted exclusively to one single purpose.

Thus the ranger manages his ranger district in a forest. A ranger's responsibilities in this day of fast and easier transportation may include 500,000 acres or better, a whole forest in itself. A forest supervisor manages a forest or occasionally a group of forests—like the four national forests of Florida, with a gross area of 1,600,000 acres. Supervisor headquarters for these four forests, all lying within the State's boundaries, is at Tallahassee, Fla. Regional headquarters, supervising the national forests of 10 Southern States and of Puerto Rico, is in Atlanta, Ga.

There are 10 Forest Service regions, named by geographical divisions and numbered from 1 to 10; but the 161 national forests are not numbered; they bear names. And almost innumerable ranger stations, springs, camps, pleasure grounds, and peaks within the forests bear names, native names that announce our history and tradition: Big Prairie, Upper Ford, Sun River, Poncha, Teton Pass, Crested Butte, Horsethief Canyon, Frying Pan, Bear Ears, Sleepy Cat, Star Valley, Shoshone Canyon, Snake River, Skull Valley, Tonto Basin, Thunder Mountain, Snake Creek, Joe's Valley, Granddaddy Lakes, Goosenest, Hayfork, Wind River, Packwood, Deerfield, Gunflint, Jackson Hole, Little Bayou, Dead Indian these are but a few of the names of ranger stations, camps, trails, mountains, creeks, tower lookouts, and side camps on the Forest Service maps.

As for the forests, their names however prosaically listed make a song or chant of the past and of the hopes of this country and its people. It is too bad that Thomas Wolfe, the young American writer who so rejoiced in American place names and rolled them forth in his novels with such sweep and gusto, did not come upon a Forest Service directory before he died. Perhaps Pare Lorentz, who made a poem of American river names in the sound-track accompaniment of his talking film, The River, will some day make a name poem of our forests. For even in the plainest prose the names of the national forests are beautiful. To call but a few:

On the island of Puerto Rico the Caribbean National Forest; the Ocala and the Choctawhatchee, in Florida. In South Carolina the Francis Marion. In North Carolina the Nantahala, and in Alabama the Black Warrior. In Georgia the Chattahoochee, and in Tennessee the Cherokee. In West Virginia the Monongahela, in Virginia the Jefferson and the George Washington. In Pennsylvania the Allegheny. And the White Mountain Forest of New Hampshire, and the Green Mountain Forest of Vermont.

Passing west: The Wayne Purchase Unit of Ohio. In Michigan the Manistee. In Illinois the Shawnee. The Hawkeye Purchase Unit of Iowa. In Minnesota the Chippewa, and the Chequamegon in Wisconsin.

Then the Prairie States Forestry Project covering parts of Kansas, Nebraska, the Dakotas, Oklahoma, and Texas. The Black Hills and Harney Forests of South Dakota. The Ouachita and the Ozark of Arkansas.

In the Colorado Rockies the Arapaho, the Grand Mesa, the Gunnison, the Pike, the San Isabel, the White River, the Uncompahgre. And up in Wyoming the Bighorn, the Medicine Bow, the Shoshone, the Washakie.

The Apache, the Coronado, the Crook, and the Prescott of Arizona. In New Mexico the Carson, the Cibola, the Gila, the Lincoln, the Santa Fe. The Caribou and the Challis, the Payette, the Sawtooth, and the Minidoka of southern Idaho. In Utah the Fishlake, the Manti, the Uinta, the Powell; and the Teton in Wyoming.

In Montana the Absaroka, the Beaverhead, the Bitterroot; and the Deerlodge and the Flathead and the Gallatin. Also in Montana are the Lewis and Clark National Forest and the Custer. In northern Idaho are the Clearwater, the Coeur D'Alene, the Nezperce, the St. Joe.

Then again over great mountains to the coast. To the south in California the Angeles, the Cleveland, and Los Padres. More to the north and inland the Sequoia, the Eldorado, the Klamath, the Shasta, the Tahoe. In Oregon the Fremont, the Malheur, the Mount Hood, the Rogue River, the Umatilla. In the State of Washington the Chelan, the Columbia, the Mount Baker, the Wenatchee, and many others.

Alaska is Region 10. It has two great national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, with headquarters at Juneau.

Thus incompletely we have called the roll of our national forests and are ready now to see what is being done with them.1

1A complete list of such forests, their location, and areas is appended on page 289, Appendix.

SOME OF THE CROPS . . . To conserve and increase all the values that any given piece of land, be it an acre of farm woodland privately owned or a 2-million-acre national forest, may yield, it is generally unnecessary to withdraw the land entirely from human use. Now and then the Forest Service takes over a piece of country so completely racked by headlong private exploitation as to seem for the time being completely useless. The timber has been hacked to rotting stumps and the land burned over. The brush cover is gone. The grass is gone. Much of the soil is gone. There is no game. The streams are foul and muddy. Such scenery as remains cries to Heaven of heedless greed and ruin.

On such scattered areas there may be nothing to do at first but bar for a while all further material cropping, let the worn land rest, coax back vegetation—grass, brush, trees—to resume its ancient work of clothing wounded earth, healing it, and holding the soil together. Lumbering is out for years to come. Pasturing is out. Hunting and fishing are out for the time being. But as the land heals, and takes on something of its former beauty, certain measured uses may be allowed.

One of the first uses possible may be for human recreation. This worn area may be nothing much to look at, as yet, but still it may be the most restful-looking piece of open country for miles around. And it is coming back; that is something. People will come for picnics, or for an hour or so of quiet and fresh air. Even a greening, protected strip of cut-over or burnt-out land in the midst of great areas so laid desolate offers, as it heals, a spot for human outings and a certain degree of rest and seclusion. But care must be taken quietly to manage and distribute recreational use so that people, playing and resting, do not destroy the returning cover.

Most national forest land is now in a far more thrifty and flourishing condition than are the cut-over areas lately taken over. Most of it can be used and is used for a number of purposes at a time. The essence of sound forest management for the long pull is not hoarding, not a grudging with holding, but wise use. Most forest or range land rightly managed can be made to yield useful crops perpetually. Under such a developing system of management material crops of the national forests returned $4,903,376 to the Treasury of the United States in the fiscal year 1939. Of this money $1,215,925 was returned, by law, to the States.

To name all of the forest, range, and desert products which entered into this reckoning would make a list that would run on for pages, even in the smallest type. Lumber, of course, stood high on the list, and grass, making meat through pasturage, returned hundreds of thousands of dollars in grazing fees. Cordwood for fuel and pulpwood for the making of paper and of fabrics, choice hardwoods to be sliced into veneers or carved into the keels of yachts or modeled into airplane propellers, turpentine and naval stores and valuable plastics and chemicals, Christmas trees, palms for Palm Sunday, curiously shaped stones from the desert, ferns from the forest floor to dress up the floral bouquets of matron, working girl, and debutante—these were among the items useful or ornamental taken and sold from your national forests last year.

Beyond such items are products whereon it is impossible to set an adequate value in dollars and cents. What value could arbitrarily be assigned the cold mountain water brought down from high, forested ranges to make scorched valleys blossom and to make life possible in the towns and cities of our arid West and Southwest? Snatched from the clouds at the crests, eased down through canopies of trees and grass, this water is the very lifeblood of that civilization. No one could really put a price tag on this water that would mean anything.

And how could any price put upon American soil, that well-managed woodland and grassland binds and withholds from washing and blowing, from death by erosion, be adequate? For a stabilized topsoil, well-aerated and rich in organic remains, is the thin film of life by which all men and civilizations live or die.

OTHER FOREST VALUES defy price analysis. But they are actual values. They make changes for the better in the ultimate crop of any country. The ultimate crop is the spirit of the people there.

Here for example is a family—any family—with a home in one of the desert towns or cities of Arizona or the interior valleys of California. Daytime summer temperatures here go to 120°, and 90° F. or hotter at bedtime is not altogether unusual at the height of summer. "You can fry eggs on the bedsprings," the people say.

What is it worth to this family to have a quiet road up the mountain and a place within easy driving distance where they can take it easy under giant trees, amid summer temperatures that range from a crisp 60° to a mildly warming 80° F. at noon, and swim in clean mountain water, and find relief from the terrific heat? In many places, ranging from humid Puerto Rico to the western peaks above the great American Dust Bowl, forest recreation becomes a downright physical necessity for the great mass of the people who ordinarily cannot afford to buy a change of air, or send the women and children away for the hot season, as well-to-do people can. And even the reasonably well-to-do, in such places, are glad to have camps or cottage permits, let cheaply but with no title, on forest land up the mountain, and send their families there, and drive up to be with them nights and week ends.

NOW CONSIDER WILDLIFE the country over. What price good fishing, good hunting, for food and for sport? What price, for the naturalist or nature lover, the sight of renewed wild herds of elk and deer and bison and antelope grazing and roaming, or beavers working? What price a continuing return of songbirds and game birds to our North American earth and sky?

The restoration of abounding native stocks of wildlife in the forests, on upland range, in the water, by the water, and on the water is a most important part of the multiple-use policy under which the national forests are operated. In many parts of our country where the game had been starved and shot almost into extinction, where the waters had been fished out, and where no birds sang, wildlife is coming back now, and fishing is getting good again.

Much remains to be done toward a fuller repopulation and a proper protection of native wildlife. The United States Department of Agriculture is but one of many agencies, public and private, that are taking the necessary first steps, more or less together, to restore to the extent possible under modern conditions the wildlife which was so highly important in America's past.

Game can come back fast: In some places deer have so multiplied as to become a sort of animal weed, wandering. They are devouring herbage and cover, inducing soil erosion, starving to death. Upward of 5 million deer were abroad in this land at the time of the last governmental wildlife census covering all lands, in August 1939. In some places the hunting season and bag limit have been extended, considerably, in order to keep the deer from wrecking what is left of cover crops and soil.

This fact raises differences of thought and emotion, highly pitched. Those who delight in the sight of deer, poised, quivering, or leaping for cover, and press a camera trigger, or make notes, cry protest against carnage. Those who tremble with pleasure, or "buck fever," then steady themselves, and press gun triggers, respond to instincts no less primitive or deep seated, differently. The only point to be made here, in opening, is that both sorts of men, and groups of men, experience at the moment wild deer are sighted a healing sense of freedom and rapture, a split second of primal delight. The pressures and constraints of civilization fall from their minds and backs; they are almost as free, for a few quick breaths, as the deer they note, photograph, or kill.

The pleasures that the national forests can offer the people are widely various. They are simple pleasures, in the main. The aim is to keep them simple, inexpensive, and as nearly as possible accessible to all. There are plenty of complex and clamorous amusements available to most people outside the forests. The forests offer a wide variety of retreats from strain and tension, with a chosen degree of solitude.

THE MAIN IDEA of those who have to plan recreational use for the forests, is to fit their plan into the guiding policy of multiple-use, and to keep things natural. That is not as easy as one might think. Millions of Americans have lately discovered the national forests as a natural retreat and playground. On summer week ends and holidays, especially, the people in their millions have learned (as one sardonic western forest officer expressed it) "to take to the open road in a closed car and return to the breast of Nature and litter it up with banana peels and beer cans."

This remark may sound a shade inhospitable. Such, really, was not the mood of this forester, still in his forties. He started work with the Forest Service at a time when, if a party wanted recreation, they simply went out into the forest and made a fire and caught some fish, and cooked them, and slept in a throw-down camp. Then automobiles were invented and were made cheap, and the thundering human herd on rubber tires entered the forest to rest and play.

You could not let them make fires now, at random. Many would be careless, and the fires would spread, destroying timber, destroying cover, incinerating perhaps ten or a dozen of these carefree forest visitors themselves. Fireplaces, camp or picnic tables, pure piped water, and sanitary toilet facilities had now to be provided; yet things had to be kept natural, or as natural as possible, lest the visiting throng destroy the very beauty and simplicity and quietude toward which with a deep and restless yearning they swarmed.

All this was somewhat bewildering to old-time Forest Service men who knew about trees and sheep and game and cattle, and knew what to do about overgrazing, but who had never been trained to handle an overload of humans, unobtrusively. They have learned. Now they "salt down" as cattlemen say, attractive and secluded byspaces, so that people will spread out in their outings, and not stomp the cover bare at some one central glade. Where denudation of the cover does take place, and soil erosion follows, foresters now shut that camp or picnic site off for a while, give it time to heal, and "rotate" the picnic or camp sites, whenever possible, to some place else.

Some of the best recreational-use planning has been done not at Washington, and not at the regional and supervisor offices, but by rangers on the ground. And many of the best jobs of welcoming people to the forest, spreading them out, and letting them have a good time in the way of their own choice, quietly, have been done by sardonic, old-time forest officers such as the one just quoted.

No one who loves the woods and the lone places can long remain inhospitable or out of sympathy with people who today throng to the woods, the shores, the lakes, and the heights of mountains on our national forests. In somewhat lonely settings these visitors may be embarrassed or awkward, at first. Certain of them may make a great deal of noise, on their own, and turn radios on full blast to make themselves feel more at home, and prove it. But generally the jitterbug phase of their return to nature soon wears off, and they seek quieter amusements, more on their own. Their need and hunger for natural things, for simple, earthy, normal satisfactions, is so urgent, so deep-seated, and so evident, that even when they spit down canyons in their exuberance and see how much of The Star-Spangled Banner they can sing before it hits; even when they perform the tenderfoot trick of rolling great stones down sheer mountainsides, dangerously; even when they complain that a one-way pack and motor trail to a mountaintop is out-of-date and should be at least a three-lane highway, paved, oiled, and sleek, you cannot for long feel cynical about these robust nature lovers, or remain unfriendly toward even the rowdiest, the noisiest, the most self-conscious. They are lost children coming home.

But they are often problem children; and the job of planning recreational use on the public forests and fitting it into other uses is difficult at times, and always fascinating.

FOR PURPOSES OF SIMPLE PLEASURE the national forests of our States and territorial possessions offer everything that unsettled land can offer anywhere on earth. They include nearly any combination that can occur in nature from the edge of deserts to loftiest summits of wind-swept rock or snow. There are the hot, dry woodlands of piñon and juniper which grow in sun-baked soil and the cool, moist, alpine forests and meadows which during most of the year are saturated with the snow and rain and mist of mountaintops. There are the abused cut-over lands purchased by the Government for the sake of restoring them to productivity, and virgin forests as untouched by commercial use as before the days of Columbus. In the Southeast, the Southwest, and the Black Hills, are forests so devoid of water bodies as to require artificial lakes and reservoirs, and in northern Minnesota and Wisconsin are forests with so many thousands of lakes that no one has ever counted them all.

Our forests include waterfalls, dry mesas, and turbulent rivers. They include timberland, range land, rock land, and desert land, all mixed together and overlapping in a pattern of endless change. Our national forests include within their boundaries almost three-quarters of the timber land in public ownership. They contain from tens of thousands to millions of acres of practically every important forest type, including the redwood.

Let us look at a few of them in early summer; for when school lets out, from then until Labor Day, that is when our forests receive the most visitors. The "peak load," foresters call it, or the "heaviest use" by pent-up citizens seeking natural recreation, comes the country over when youngsters are out of school.

On the upper slopes of the White Mountains in New Hampshire the red spruce and balsam grow in dense stands and keep the ground cool and shady even in the hottest weather. The alpine asters and goldenrods, the Indian pokeweed, the goldthread, and the sphagnum moss are fresh and untrampled. Through the forests young streams splash wildly over granite boulders as they tumble on the first leap of their journey to the sea.

In Pennsylvania the foliage of the hemlock-hardwood stands is a mixture of dark-green needles and bright-green leaves. The larger trees display a pleasing variety of patterns. The hemlocks are brown, with shallow grooves in their fibrous bark; the maples deeply grooved and tan; the black cherry trees, red-brown and lustrous, with their horizontal bark scars; the beeches a smooth, hard grey, spotted with the black conks and healed-over branch scars. On the floor of the forest are the twinflower and woodsorrel and lady slipper and saxifrage.

The hardwoods in the coves of the southern Appalachians grow higher than any other hardwoods on the continent. Here the straight boles of the tulip poplars rise more than 100 feet without limbs and jut up far above the surrounding oaks. In the small openings of the forest grow dense clumps of laurel and azalea which in May and June blossom forth in brilliant orange and pink and cardinal.

Between the innumerable bodies of water which cover northern Minnesota are varied forests. The sandy places are clad with white and red pines. The white pine has short, delicate, light-green needles. The foliage of red pine is long, coarse, and dark green. As you come off the lakes and start to portage through these pine forests, the trail leads into an unknown world of exciting mystery. Spruce and balsam grow in the moister places, and among them the tundra vegetation of labrador tea and pitcherplant and sheep laurel. Wherever forests have been burned in the past hundred years you see hillsides covered with aspen. These aspens turn a quivering, brilliant yellow in the fall.

Throughout the interior West, from the Black Hills to the eastern Cascades and from New Mexico to the western foothills of the Sierras, are beautiful forests of ponderosa pine, covering millions of acres. The mature tree trunks appear almost orange color in the bright sunlight of this western region. Darker-colored Douglas firs grow among the pines and lend variety to the landscape, and the ground is gay and bright with green forage. The forest here is invitingly open and parklike, almost without underbrush.

In northern Idaho, the western white pine dominates the forests. For more than 175 feet it rises tall and straight, and for half of this reach, or more, it is free from any branches. Beneath it grow the cedar and hemlock, dense-crowned trees. The limbs extend almost to the ground and cast a deep shade on a forest floor carpeted with delicate woodferns, twinflowers, gold thread, and wild ginger. Scattered throughout these stands is the western larch with bark that is sometimes a foot thick, and needles that turn pure gold when touched by the frost.

All through the Rocky Mountains, from Canada to southern Colorado, the lodgepole pine forests cover millions of acres. These trees are slim and straight. Often they grow so densely together that you have to fight your way through them. In mixture with the lodgepole pine you see Douglas fir and the true fir. The ground cover is of sedges and grasses of many kinds, together with the bright-blue lupine, brilliant orange tiger lily, and many other cheerful flowers.

The giant forests of western Washington and Oregon are majestic and solemn. They are like vast cathedrals, out of doors. Here are lands of perpetual shadow formed by the dense crowns of Douglas fir and Sitka spruce, which grow more than 250 feet tall, and of the shorter hemlocks, cedars, and white firs. Their branches are draped with long, hanging tree moss which gives to the surroundings a veiled appearance. On the floor of the forest only the most shade-enduring vegetation can live, but this includes ferns which frequently grow waist high. Such forests convey the feeling of the everlastingness of life. Here stand all ages and sizes of trees, from the overmature giants, 5, 10, or even 15 feet in diameter, to the current year's seedling which is less than an inch tall, but sprouts hopefully on the disintegrating, moss-covered remains of some ancient specimen that had tumbled long before Columbus came.

The alpine forests of many high western mountain ranges are lighter, brighter, and more cheerful. Here the trees are scattered and stunted from a lifetime of battling against the cold and wind of high altitudes. And strewn between the throngs of battling trees are alpine meadows, carpeted with fresh green grass and a gay profusion of many-colored flowers, but recently born after a hard winter of dormancy under snowdrifts unbelievably deep.

These in general are elder woodlands, our more primitive forests, such as remain. Recreation on the national forests is by no means confined today to the primeval setting.

NEW WOODS AND WAYS . . . Millions of acres of vigorously growing younger stands which have followed fire and logging, millions of acres of meadows and browse lands where people come for relaxation and adventure, have been opened to the public within the last few years.

New ways of public entry have been opened to old forests, and new. These roads have been planned and made to give more comfortable access to the forests, yet not intrude unduly. They offer to the tourist a great variety of picturesque driving possibilities. The Mount Hood Loop Road in Oregon, first following along the mighty Columbia River, then swirling upward to circle this beautiful volcanic summit; the Galena Summit Road in Idaho, switchbacking up to and down from this lofty pass; the Mogollon Rim Drive, skirting for miles along the top of massive Arizona Cliffs; the Evans Notch Road, leading in graceful curves among the rugged hardwood slopes of the White Mountains—these are a few of the new main roads into great new forests, or into older forests, tended and renewed. And thousands of miles of new trails have been built, mainly by CCC boys, into the forests, for the people's use. They vary from easy footways over level or rolling country to steep trails scaling rocky summits far above timber line. These trails are marked with arrow pointers, plainly; back to comfort and civilization; on to somewhat lonely natural wonders, beauty spots, or heights.

But you have to make the journey on your own leg and lung power and learn again in some measure how to take care of yourself in far places, with no corner drug store near, and with the unpredictable beat of the weather on you, if you really want to return for a while to nature.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap1.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |