|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part One

EYE TO THE SKY, FOOT TO EARTH

Chapter Two

Americans Need Outings

"The New World": at a time of tremendous pressure and distress, that phrase rang through Europe to lift the hearts of the defeated, restless, and dissatisfied. It aroused hope of romantic adventure and of sudden riches in gold and furs. But those who came to settle there found that pioneering must be paid for in sweat, blood, and strange diseases, in the suffering of long, slow toil.

They paid that price, and the heritage they leave us is rather bitter—a rich land racked and mismanaged, with huge accumulations of goods and wealth, yet with millions of our people deprived and helpless. Today we again have a situation like that in Europe 300 or 400 years ago. In some ways I believe it is far more significant. We have millions of people with good bodies and minds who cannot get jobs. They are just as good people as those who left Europe for America 300 years ago. They are looking for another new world.

Henry A. Wallace, New Frontiers, 1934.

WHEN THIS LAND WAS NEW and open for the taking, the amount of work that had to be done barehanded or with the rudest of tools was staggering. Need never drove harder than on the first English seeding-ground of occupation. "He that will not work shall not eat," wrote Capt. John Smith in that fearful "starving time" at Jamestown; and it is recorded that toil remained a virtue of necessity during those first winters on Massachusetts and Virginia shores.

But something far more enduring than driving physical need entered into the minds and hearts of these new American inhabitants. For here were people seeking freedom, and this gave a spiritual lift and push to the march of occupation, exalting it. Here vast wealth lay almost at the door of every settler, wealth in the raw. The extent of it seemed endless. The race was to the strong. And although the price was toil, the reward of toil was the prospect of independence, freedom the right to stand on your own legs on your land, owned free and clear; the right to look all men who differed with you in the eye, and tell them where to go.

That was the dream. But with so much virgin country to be developed, and so few hands to do the work, idleness seemed sinful. It was only by the hardest of labors, long endured, that a man without capital, and his wife and children, could stand free. So pioneer Americans all but deified constant toil as a means of freedom, as a means of attaining security and dignity; and they lived, in the main, scorning ease.

|

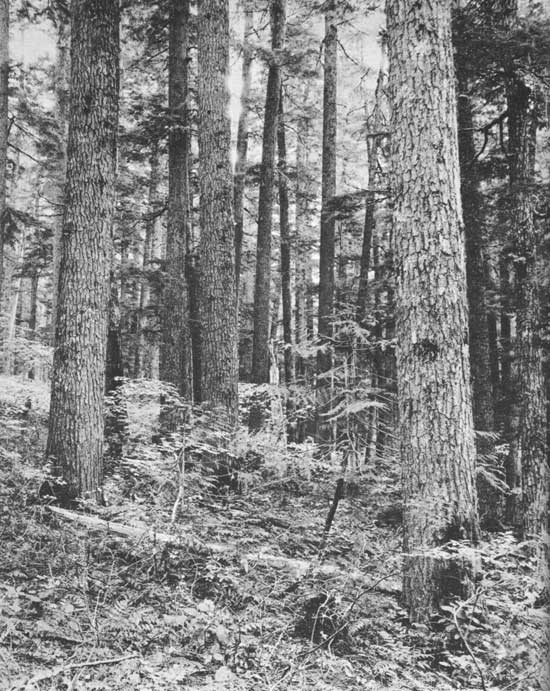

| . . . Virgin forests as untouched by commercial use as before the days of Columbus. COLUMBIA NATIONAL FOREST, WASH. F-321029 |

THE SCORN OF EASE was never as intense southward, in all likelihood, as it was among stern and rock-bound Pilgrims facing west. Nor did natural circumstances in the South enforce, until many years had passed, the thrift and care which we associate with New England. New England soil, as one student of geography and its relation to history has in effect observed, was only to be taken and held by patient husbandry; but the warmer and more opulent South lay open to ravishment right away.

Tobacco, soon introduced there, brought money rolling in from overseas. It multiplied negro slavery, but it lightened the lot of the white proprietors. Tobacco was a cash crop, but it was a clean-tilled row crop that punished land. Washington ordered tobacco off the soil of Mount Vernon when he saw what it was doing to his fields. Chop, crop, and get on West continued, however, in the face of his warnings, and Jefferson's, and Patrick Henry's. For many years it remained the prevailing mode of development and progress.

Cotton also levelled great forests, ripped up pleasant grasslands, and assumed an all but absolute sovereignty over some of the best land in the United States. It was also a cash crop, and year after year cotton also exposed Southerners' land to the weather, let the weather whip their film of sustenance, their topsoil, out from under them. So year after year the fields of our southern coastal slopes ran off into the Atlantic Ocean.

This set going a definite human drain. The South, by fairly constant emigration, has contributed flesh, blood, and many of its more adventurous human spirits to the North and West. This drain has accelerated in recent years. Gerald Johnson, interpreting statistical tables compiled by Howard Odum of the University of North Carolina, estimates that the exodus of Southerners, considered in point of quantity alone, has exceeded 3-1/2 million; and that to rear, school, and then lose this many men and women to other parts of our country, cost Southerners at least 17-1/2 billion dollars.

ON THINNED SOIL, HEALING, the South is now coming back. Safer methods of cultivation are developing fast, and being adopted. Healing pine and hardwood are being permitted and encouraged to reforest the worst-torn, cropped-out areas. Second-growth and some surviving virgin timber are being brought under management and cropped with a view to permanent security, pleasure, and gain.

Grassland is coming back, too, but on the most-eroded areas forests must be the mainstay for centuries to come. For although nearly all the topsoil there is gone, there are many trees which can feed on subsoil and flourish. And trees bring up through their roots and trunks and limbs and foliage mineral and organic nutrients that are below the reach of lesser plants, slowly rebuilding topsoil with the years. Within the present century more than 11 millions of acres of national forests have been established in the South alone, and the State forests there now exceed 254,000 acres.

The South is coming back; but you will find little of the lavish old plantation atmosphere, the gay outdoor court life, or the soireés which attended King Cotton at the height of his reign. For the New South is a land of hard work and of rather grim and steadfast purposes. Most of its people are engaged in the tiring, unromantic business of actual long-time reconstruction from the ground up. The tourist business brings in money, and so is welcome. But the thud of the tractor, the plod of working gangs and work mules, the rising whir of new and diversified factories, and of a great woods industry these are sounds that seem more important to the South than banjo music now.

WORK—AND ESCAPE . . . It is a common observation among the people of older countries that Americans work like mad, play like mad, and do not know the value of leisure. There is some truth to that. Surely we work like mad, many of us, and take a strange, perverted pride in it. The remark of a farm wife, "Overwork is the most dangerous form of American intemperance," suggests habits certainly not confined to excesses of weary, stumbling toil afield. Great executives and lesser ambitious officers and clerks of our greatest city business firms send out for a sandwich and milk shake, then nibble at their desks as they dictate, push buttons, grab at phones, bark, and display in excessive and sometimes hysterical form all day long and after the electric lights are lit good old 100-percent pioneer American drive, pep, and spizzerinctum.

Then these businessmen clump wearily to their feet, all possibility of a sane and collected judgment long since dulled. No hay hand bragging at the fifth beer of inhuman feats of overexertion under the blazing sun of a Montana harvest is prouder than the wan slave of business, be he the president of the company or a file clerk, who is the last man out of such an office for the day. The last man out turns out the lights. That is his privilege, and an omen.

And not unusually these hired men crawl home through traffic by car, bus, or subway laden with bulging brief cases and portfolio; more work. They snap at their dinners and their families and perform further lonely prodigies of toil. And when such excesses drive them, as happens fairly often, to alcoholic frivolities, to the divorce courts, and to the waiting rooms of highly specialized doctors, these tired businessmen are very sorry and somber about it. Then, if they are wise, the doctors advise them to seek escape, to take to the woods, to strike out into the wilderness and get away from it all.

THE GREAT OUTING . . . The days of our pioneering are not ended. But our simple and brutal concepts of pioneering are changing. We no longer look at it as altogether doleful or as a matter for long-faced lamentation. Why should we, for in a manner of speaking the whole American settlement from coast to coast was an adventure, a grandiose outing, a burst of escape from overcrowded, overdriven civilizations that were not working any too well in Europe.

It was rough work, especially hard on the women, who like things convenient, orderly, dainty. But in most males there is a rough streak. They find relief in rough clothes, rough food, rough ways; in telling rude jokes, and letting the whiskers grow; in pigging it, as campers say, with an unabashed and primitive abandon. And such a life seems all the more satisfying to rude males if it is spiced with danger enough to permit a certain amount of strut and heroics. There is evidence that a great many of our American male progenitors and not a few of their women had in their more exalted moments a grand time. The life was hard, but you felt that you were doing something special on your own power; and it kept you out of doors.

Our frontier forebears had so much of nature all around them, and hammering at them, that they did not go into rhapsodies at sunsets. They made no undying lyrics, as did pale Shelley confined in London recalling the flight of a lark. They did not sentimentalize or often speak of such beauty and wonder, any more than most forest workers and farmers do today. But the woods and unspoiled natural places lay just beyond their fields or over their doorsills, and their work was generally such as took them outdoors alone through all the changing seasons.

They were there on business, but even if the work and their conscience drove them, the virgin beauty and wonder surrounded them and worked its spell. They were there on their own, as the saying goes, and they could imagine themselves free. The men who conquered the wilderness did not hate it. Outdoor escape was inseparably a part of their pioneering. We who follow come honestly by our love and yearning for outdoor recreation. The wide outdoors is in our blood, and we need the healing shelter of woodland.

Any open country will do for an outing. But in our forest land there remains something virile, yet mysterious, something that exerts a special pull upon a people still steeped in pioneer traditions. In woodland we still feel a bracing sense of uncertainty, a hint of danger. Actually it does not require a two-gun man or an athlete to sojourn in the forest. Yet a man goes into deep woods with some hesitation as to his ability to cope with what he may find there, whereas even a billionaire centenarian confidently totters out on a golf course. To Americans the forests mean adventure. In many places, the forests still are primitive enough to provide adventure, and this adds to the charm.

In a personal letter, Rex King, of the Forest Service, at work in the Southwest, lately sought to express in words the compulsion which led him years ago to leave New York, his native city, and take work in a natural wilderness. "As a boy," he recalls, "there was a sort of legend, a promised land, that we used to hear of, we fellows who lived in New York. It was 'The North Woods.' I don't remember that anyone ever stopped to wonder just where the North Woods was located, but it was somewhere a long way off. It was a place where there were lots of trees and rivers and lakes, where one could live a long time without seeing people, and there were many birds and animals. We were old enough to know that there were no longer any Indians abroad that there were no dangerous animals, but there was still the expectancy of adventure. Even today that term 'North Woods' brings to my mind something which I have never found in reality, although I have looked for it pretty well over the United States.

"It seems to have meant something of a remnant of those things which our ancestors had experienced breadth, freedom, great spaces, fragrant air, clear water, and perhaps just lonesomeness."

"I WANT OUT" is a Pennsylvania-German expression that is also heard occasionally in parts of Ohio, Indiana, and other States settled by pioneers who came in from Pennsylvania over the Cumberland Gap. They use it as a definite literal statement of purpose, to bus conductors, for instance. Also, upon occasion, they say, "I want up," "I want down," and "I want in." But: "I want out," is the sentence which rings now with its stark directness and urgency in the mind of anyone considering the growing pains of demand upon forest recreational resources in the United States.

There are times when we all want out, and times when the fret and strain of modern life are such that this want becomes no mere whim, but a dominating necessity. We all rebel at times against the regimentation that commerce and fashion and custom, far more than our Government, impose. And if our inherited sense of personal rebellion can be diverted and soothed by wearing a dirty shirt, tramping lonely trails, and going without shaving or tinting our fingernails for a day or so well, that would seem a rather harmless way of trying to get another revolution out of our systems.

|

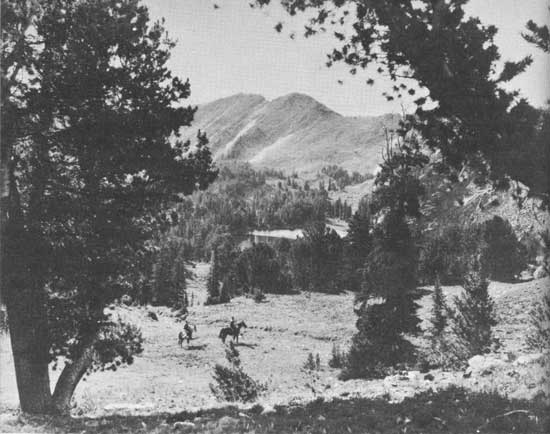

| Men seek escape. They yearn to get away from it all. WISEMAN'S VIEW PISGAH NATIONAL FOREST, N. C. F-350162 |

Modern life and urban life in particular enforces insistent and inescapable discipline upon the individual. Social customs, job, family, the group, and the church all demand compliance to codes. Many of these rules are irksome. Some of them run counter to human nature. Often man is forced into a pattern of behavior that makes him an indistinguishable member of a band. This may tend in the course of time to subdue his pride and his sense of importance.

A man must learn to live with himself before living with others. He feels that this loss of the sense of an individual significance is not good, either for himself or for society, and he gropes for means to recapture what he has lost.

Many forms of urban entertainment enable a man "to get out of himself," and often they allow him to identify himself vicariously, by feats of personal imagination, with heroic or striking and successful personalities. The theatre, the movie, athletic sports and spectacles, romantic novels, and group organizations momentarily may restore his esteem of himself. But vicarious participation in the triumphs of others cannot for most natures forever be a substitute for active participation and actual personal triumphs.

So there are a large group of games and activities possible in urban environment designed to give modern man a chance to excel in himself. He may play at golf, at tennis, at cards, at squash, at swimming and fancy diving. But in all these pursuits, he is hopelessly outclassed by the publicized expert.

The more active of all such games afford needed physical exercise, and a momentary psychic relief. But there remains still the need to get out of the city, to "fall out" of ranks, as army sergeants command, if only for a day or two, or even for an hour's drive in the car. The urgency of this need is evident to anyone who has to drive in week-end traffic around our greater cities. Even where the gas fumes, billboards, and hot-dog stands are thickest, the people in their millions seek a change of scene and air. Modern man most desperately seeks escape. He drives hard, when no policeman is near, to get out of his daily routine; he will break speed laws and jump red lights to recapture the chance to relax. And in city and country alike people have need of variety, of mixing work and play, of seeing and doing new things, of gratifying curiosity, of personal adventure.

REST AND CHANGE . . . Physicians, psychiatrists, and others dealing with human ills generally recognize this. "Rest and change" was perhaps the most frequent prescription of wise family doctors, general practitioners, years before they or their patients learned to speak in terms of psychiatry. And even now when we have a whole new set of words to describe physical and mental fatigue and spiritual exhaustion, the cure in many cases is just as simple. And each year the cure becomes more nearly impossible for many poor and driven people.

When body and mind are run-down to the verge of prostration, when nothing as yet is organically wrong with that mind or body, the most skilled and candid of physicians recognize that they can do little for the patient beyond inducing a slackening of tension and activity, then aiding or allowing Nature to heal the hurt. "Rest and change" is still a standing prescription, and "Try and get it!" remains a common American response.

It is generally true that Americans, rich and poor, are learning to be their own doctors in this particular, so far as they may. As naturally as ailing or wounded animals crawl off from the pack to recover, we are learning to quit wounding environments for the time and to seek such relaxation and change as our means allow. To a considerable number of Americans not very rich, a summer vacation on farms taking boarders, or at "camps" with names like Kare-Free1 in the Catskills, allow for a while a slowed-down tempo, a chance to rest and recover.

1The imagined but factually accurate scene of Arthur Kober's beautiful and tender comedy, "Having Wonderful Time." Kare-Free has a high-powered recreational director and frequent dances and vaudeville as an extra added attraction; but that is not its main attraction for the shop girls and garment workers of New York City who come to the North Woods for a breath of woodland air, rest and romance, year after year.

Ocean or lake beaches nearer to great cities and the job receive enormous crowds of young and old. This is emphatically true of New York's commercial playgrounds during the hottest weather, from Independence Day to Labor Day. During heat waves the beach at Coney Island photographed from a 'plane resembles nothing so much as a vast anthill swarming. In point of recreational use this beach probably carries the heaviest load in the Nation.

Local police complain that the thousands of tottering children customarily taken up as lost, and at nightfall generally reclaimed by their parents, were not really lost at all, but were mainly turned loose to be lost for the day by overdriven parents. The New York papers customarily carry air photos of the thickest of these heat-wave swarms in the Sunday rotogravure sections, and no news account by a trained metropolitan reporter omits as a sort of key to the extent of the exodus the number of "lost" children picked up and tended for the day by the Coney Island police.

It is plain that such mass outings, while valuable, leave something to be desired. The incessant pressures of urban time schedules, of space restrictions, the noise and the huddle of a metropolitan existence still beat at the mind and cramp the spirit amid these tangled beach throngs. The beach at Coney Island on a hot Sunday provides air, sun, and ocean enough for all, but certainly it is not an ideal place to recover a lost sense of personal significance or find new elbowroom for the ego. And it is one of the sights of New York City to see these sunburned, tense, and jaded pleasure seekers pouring back into town at the end of their day in the open. The poorest of them pack the tube and subway trains, pushing and stomping. They are tired to the point where they can almost sleep standing. At the ferries the automobiles of somewhat more solvent citizens stand jammed in line for miles, crawling, stopping, waiting; sometimes they have to wait for hours to get the car on a ferry. Their auto horns keep up a constant caterwauling of agitation and protest all through the night. There is a great crying of weary children and a great slapping of weary children for crying.

|

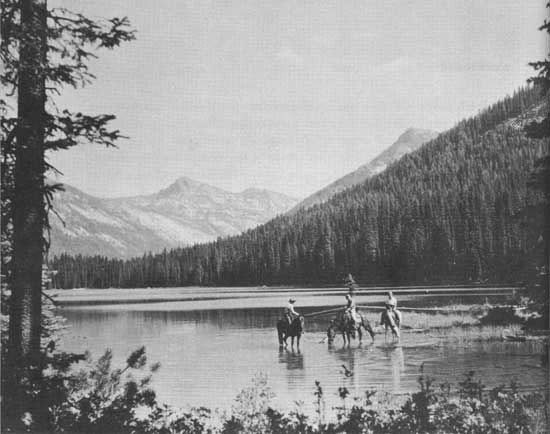

| What the national forests have to offer, above all else, is space—space and stillness. BLUE PARADISE LAKE, GALLATIN NATIONAL FOREST, MONT. F-366206 |

Now these people know from experience, most of them, what their day at the shore will cost them in money and in discomfort, but they keep on going again and again. Nothing could more plainly testify that outdoor recreation is a driving human need. These driven people are simply trying to get all they can of it within their means and scope.

>With the need as it is, with great public pleasure grounds open to the people, it becomes a matter of common-sense policy to see that public recreational facilities do not simply duplicate existing commercial facilities, but provide values that a private resort, be it Coney Island or Newport, generally cannot provide. This is especially true of recreation on the national forests.

What the national forests have to offer, above all else, is space—space and stillness. Rich people can buy this, in some measure. But only the very favored few are in a position to buy themselves enough of it in the form of suburban or country estates, country club privileges, membership in exclusive shore communities, and so on. Only about 1 percent of our city people, at most, are rich enough to buy enough space and stillness to satisfy that need in themselves, their families, and their friends. If this is a reasonable estimate, it follows that 99 percent of the outdoor recreation problem of our city people cannot be solved by the individual efforts of the persons immediately concerned.

Outdoor recreation for urban populations has become, then, a problem that seldom, if ever, can be expected to solve itself. Only 1 percent of ocean and Great Lake shores, for instance, remains open to the public.

The need for public playgrounds—using the term in the larger sense—has been recognized in this country since the early settlers began to build up city communities. The public "common" so characteristic of New England cities was one of our earliest gestures in recognition of the need for setting aside ample space for simple recreation. City parks were another step toward sustaining simple natural values out of doors. It is now the recognized job of many a city government to provide play space for its citizens. It is held a matter of civic pride that such playgrounds should so far as possible preserve beautiful natural settings. And of late, with continually greater willingness, Government is accepting the task of devising and furnishing effective outlets for the innate craving of its citizens for outdoor exercise, relaxation, and refreshment. The job of general recreation is gradually being accorded the same basic importance as that of general education. It has become a public responsibility, recognized alike by county, State, and Federal Governments.

REFUGE is provided for fish and game; why not for people? Refugees from the strains, the disillusionments, and the personal indignities imposed by a regimented commercial order of life in cities, towns, and on farms are seeking by the millions the healing refuge of our remaining undeveloped places. The people are thronging upon the more than 15 million acres in State parks, forests, or forest parks; upon 9-1/2 million acres of national parks; upon 176 million acres of national forests, the country over. Conditions, circumstances, and opportunities are so various among these public properties that different types of administration seem wise and necessary, and increased demands raise questions of recreation administration which concern State foresters, members of the National Park Service, and the United States Forest Service alike.

The results, most likely to follow, were the process allowed to increase and accelerate absolutely undirected and ungoverned, would be simply an old story repeated. Rushing, seeking to get away from it all, people tend to take it all back with them, and so clutter up, maim, or destroy the natural beauty, quietude, and freedom they impulsively seek.

In a manner of speaking, then, the problem comprises the whole problem of civilization. Here are a people sick at heart in the main of jungle drumbeat to swingtime poured into their homes, day and night, under guise of recreation over that magical modern instrument of instant communication, the radio. We are sick of noise, bewilderment, confusion; of the imitative, step-it-up technique by which so many of our magazines, talking pictures, tabloids, comic strips, books, and advertisements seek to divert and comfort us. So we pack the car, pile in the family, hit out for the woods—with a pile of magazines on the back seat, and the radio blaring full tilt.

Society may move to restore what it has destroyed or maimed. But to impose strict supervision upon Americans seeking national-forest outings—to herd them, however tactfully—is to thwart the very spirit of the adventure, to slap down any developing spirit of rest and sense of freedom. The wish and impulse of the Forest Service is simply to turn all these millions of forest visitors loose, to govern or regiment them not at all. But experience shows that on more heavily used recreation areas some rules are necessary.

It is quite a problem. Even so, when it comes to national-forest recreation the Jeffersonian tenet that "the best government is the least government" still stands.

|

| Refuge is provided for fish and game; why not for people? SELWAY-BITTERROOT WILDERNESS AREA, LOLO NATIONAL FOREST, IDAHO. F-351726 |

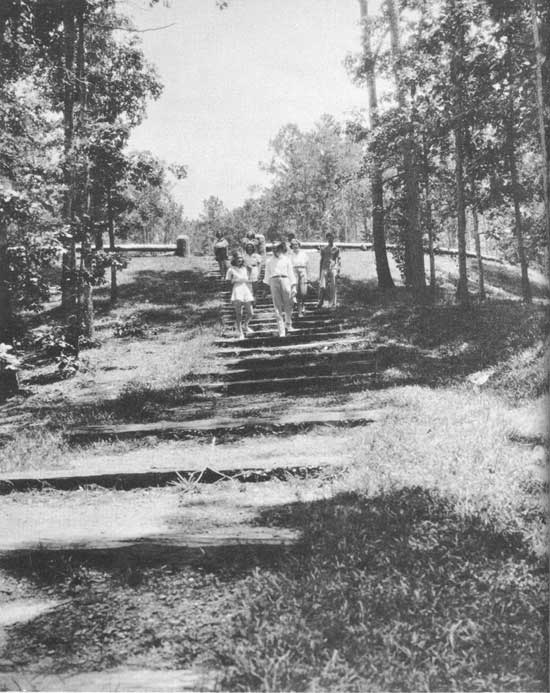

OBJECTIVES . . . The first objective is to provide a natural and simple environment. This calls for such simple and human administration as will encourage individual enjoyment of the forms of recreation natural to the forest; as will maintain as much as possible of the native simplicity of the forest; as will avoid man-made refinements not required for the protection of the health, safety, and reasonable convenience of users, or for the protection of the forest property.

A second objective of national-forest policy is to provide graded steps through which the individual may progressively educate himself from enjoyment of mass forms of forest recreation toward the capacity to enjoy those demanding greater skill, more self-reliance, and a true love of the wild. Most men or women previously unacquainted with the forest in its natural state would experience discomfort and fear, and might even be in serious danger if moved in a single step from the accustomed city to the unaccustomed wilderness. But if progressively they may experience the urbanized forest park, the large forest campground, the small camping group, the overnight or week-end hike, and so gain a sense of confidence in their own resourcefulness and lose the fear of wild country, then the final step is simple and natural.

A third major objective is protection of the resource against the added hazards introduced by recreational use. Protection of forest land involves not only extension of the customary protective machinery against fire and other enemies of the forest, but also the institution of administrative measures needed to prevent the destruction of recreational values.

The values to be defended are not only quantitative values, such as size and density of timber stands; but qualitative also. Each forest type has its individual scenic possibilities, variety of vegetation, contrasts between open and closed forests, patterns of color, ever-varying natural composition of the scene. These combine to produce a composite quality, ranging from the uninteresting and monotonous to the wild and majestic, and all in basic contrast to the environment in which most people live.

|

| The first objective is to provide a natural and simple environment. CLEAR SPRINGS RECREATIONAL AREA, HOMOCHITTO NATIONAL FOREST, MISS. F-381094 |

And there are other aspects of the forest even less obvious, little known, but vastly important. Viewed at a given moment in its natural state, any forest appears fixed, unchanging, static. But the status of the moment is the end result of an age-long conflict of each class, type, species, and individual form of vegetation with the whole environment of soil, temperature, moisture; of each species and individual with the exact environment of particular spots in the whole; between neighboring individuals to capture growing space, light, moisture; between every rooted tree or plant and such parasitic and destructive biotic forms as fungi, mistletoe, and insects that draw life from the life of the plant; and finally with the catastrophic forces—lightning, wind, fire, flood that may annihilate individuals, species, or whole forest societies.

This process of struggle and competition is never ceasing, though usually invisible. It is as fervently and ruthlessly fought as the most savage of human wars. In it, individuals, species, and whole forest societies win or lose often on relatively trivial and insignificant changes in the alignment of forces. Slightly more or less moisture, an increase of tree-killing insects, the deposition of silt by a flood; any one or all of these may have a decisive effect on the changing tides of battle. Inwardly the forest is powerfully dynamic, never static.

Modern man in general is a timid adventurer outside of his accustomed haunts. The very young may hunt or elude wild Indians in city parks in fearless imitation of grown-up Indian fighters, but the great number of adults who lack any personal experience in the friendly forest of today have a deeply founded suspicion based upon the forest's ancient hostility to man. The only way in which these inexperienced urbanites may overcome this suspicion and learn the values native to the forest, a feeling of safety in it, a capacity to enjoy it, is by gradual adventuring for pleasure.

As the frontiers pushed westward, as the forest was subjugated, as order, safety, and the rule of law were established, as men escaped from the neverending labor of the pioneer and acquired leisure and means, forest recreation began its growth. First, hunting and fishing for sport rather than sustenance. Later, the festival, the camping party, the picnic as a brief escape from the congestion of the city or the chores of the farm. Still later, mountain climbing as a sport, nature study, and winter sports; and last of all, enjoyment of the wilderness—from which America had so recently been wrought.

Today, Americans in general exhibit a restless interest in forest hunting, fishing, camping, picnicking, mountain climbing, hiking, nonprofessional study of wildlife and geology, nonprofessional collecting, riding, swimming, boating, exploring the wilderness, cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, and auto touring.

The range of the list suggests that no one of these diversions is in any real sense in competition with the other. The dyed-in-the-wool deep-sea fisherman may well have a lofty scorn for those anglers whose delight is to beguile 10-inch trout from a willow-shaded brook. The devotee of ocean swimming quite possibly regards the wilderness lover as mildly, if harmlessly, insane. The confirmed deer hunter, accustomed to arduous work in following his favorite sport, may recognize with broad charity but little interest that the, to him, passive and purposeless sport of boating does have an appeal to many.

Yet all these forms of recreation, when practiced in the forest, have common characteristics. Like the forest, they are in sharp outward contrast to the usual environments of life—as different from them as the electric stove in the steam-heated city apartment is from the open campfire at the edge of the lake. They have the inner aspect of naturalness, freshness, simplicity, cleanliness, and a more or less primitive quality, in equally sharp contrast to the artificiality, monotony, elaborateness, and sophistication of the city.

All these things belong to the forest. They are in tone with it and inseparable from it. They remove man from the dominance of artificial patterns and schedules and bring relaxation and leisure. There he need encounter no time clocks to punch, no trains to catch, no jostling, no elbowing, no narrow walls and fetid air, no split-second dashing from one pressure task to the next. Forest outings offer full play for a while to any choice of occupation. Humans may seek adventure in their own way and on their own terms—hunt, shin up a mountain, or loaf—and thereby capture a sense of freedom personally. They are removed from the necessity to meet business engagements, to keep books, to write letters, to tend a machine, to keep house. They can live for the moment on their own. They can wear the clothes of their choice, eat when they please, loaf or work, go exploring, or go to sleep, undisturbed. They may catch the largest fish, build the best campfire, bake the tastiest Dutch-oven bread, climb the highest mountain, or discover the most breath-taking view. They have the chance to regain physical and mental tone; to achieve satisfying, wholly personal proof of their abilities and prowess; to recapture a sense of their own personal significance, and to rest.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap2.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |