|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part One

EYE TO THE SKY, FOOT TO EARTH

Chapter Three

Guests of the Forests

. . . There is nothing so much alive and yet so quiet as a woodland; and a pair of people, swinging past in canoes, feel very small and bustling by comparison.

I wish our way had always lain among woods. Trees are the most civil society.

Robert Louis Stevenson, An Inland Voyage

EACH YEAR THEY COME, more and more of them, seeking the lost far places where time is stilled and care forgotten in the long stillness. In our West you will most often find them and most widely scattered; for the West is closer, both in point of time and miles, to its natural outdoor sources than is most of the East.

Outdoor recreation—"going up the mountain"—is a recognized natural part of the general life out there. From the country of the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean there is scarcely a town that does not lie within rather easy driving distance of a national park or forest. Families can pack the youngsters into a car and drive out to the nearest campground for a picnic supper. The men fish or play or loaf and the children swim or romp while the shadows grow long. Then when night falls and the stars come out, they gather around the campfire and sing or play games or talk until it is time to go home.

|

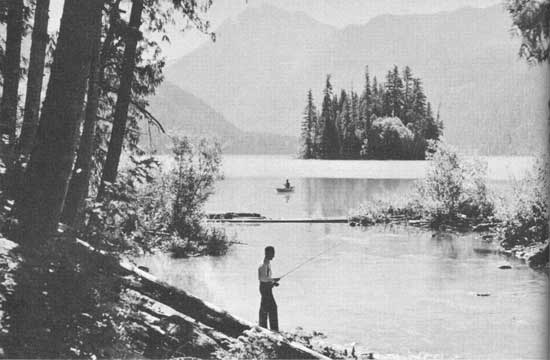

| Men take their vacations far from home where the trout jump and the mountain trails lead away to the peaks above timber line. PACKWOOD LAKE, COLUMBIA NATIONAL FOREST, WASH. F-356419 |

In the West they know better than easterners know, as a rule, how to take care of themselves in the open. They are closer to the time when they had to, on their own. But East or West, wherever you find them, they are pretty much the same people that you meet next door, across the street, or anywhere in this country that you travel.

From out on the sweltering plains of the Rocky Mountain front come dusty farmers driving a hundred miles or more with a tent strapped on the back of the car. They climb to the cool greenness of the Black Hills or the wind-swept slopes of the Big Horns and spend the week end or perhaps just Sunday. Sunburnt farmers of the Idaho wheatfields and sturdy mill hands take to the hills with their families, club members pack up for a Sunday outing in the forests where they practice their hobby and play games and take life easy. Store hands and drug clerks, firemen, and police men go into the woods where the nights are cool.

Men take their vacations far from home where the trout jump and the mountain trails lead away to the peaks above timber line. Families drive from Denver west over the divides to the spruce-rimmed lakes high on the mesa country. If time is short, they will drive all night with the children asleep in the back seat. Adventurers pitch camp and pack into the wilderness where only a trail or a blaze shows the path of man.

Youngsters working early or late shifts at the mills get to the nearest lake to swim and laze in the sun. Small boys pack a bit of canvas and a few cans of beans and eagerly make their way to the nearest water hole where they fish and swim and explore to their heart's content.

To go as a forest guest, yourself, with a car or pack train and tentage; to see and talk with many different people out there enjoying themselves; to forget, or to forget to mention official connection and interest in the spectacle that is the only way really to understand what forest recreation is in this modern time and age. The notes which follow were so obtained. They are sketches of actual people—candid shots of camper guests at actual sites on national-forest land.

YOUNG COUPLE FROM SPOKANE . . . Here the northern Rockies stretch like long fingers into northern Idaho. Between the tree-covered slopes of these ranges lies Priest Lake, 20 miles long, on the Kaniksu National Forest. Only one shore of this lake is accessible by road and on this side lie the free campgrounds where this young couple from Spokane were spending their 2 weeks' vacation.

All afternoon they lay stretched out on the wide white beach in the heat of a July sun. Their bodies were tanned, their eyes shaded with dark glasses, their elbows propped upon towels as they read. They had a little wire-haired terrier named Susan. Every now and then Susan besought attention. The man would rise and throw a stick out in the water for her to chase. His name was Ralph. He was an engineer. His wife, Ann, worked in a Spokane library and they were taking their vacations together.

Ann stretched lazily and sat up. She brushed the sand off her bathing suit and threw a pebble at her husband.

"What say to taking a plunge and then making tracks for supper? I'm hungry." She looked out over the lake. It lay clear and rippling. The far shore hung in a blue haze with the mountains rising deeper blue beyond. Voices floated up from the resort down the beach, and far out over the water a motorboat droned.

Ralph sat up. "Gee, but I'll hate to leave this place and go back to work. What's the idea of working, anyway, when you can live like this?" he said.

They swam far out, then back.

"Beat you up the bank," she called as she ran up the path to their tent. Ralph laughed and picked up the things on the beach. The shadows stretched out to the water but the sand still felt warm. He could just see the ridge of the tent between the scrub growth and firs at the top of the bank.

They ate on the rough log table. The smoke of the supper fire curled lazily up through the trees. After they had washed the dishes they went for a walk on the beach. The lake was quiet with early evening stillness. The mountains were purple now, rising peak on peak into the blue. The moon came up, painting the world with silver.

They swam again, lazily breaking the path of the moon. When they came in, Ralph built a fire of driftwood on the beach and toasted marshmallows. Ann was sleepy. She lay wrapped in a blanket with her head on Ralph's lap, watching the flames, and Susan, the dog, curled up by her knees. Once in a great while a car shuttled down the camp road behind them. Little waves lapped on their boat drawn up on the beach, and the wood fire crackled. "It sure is nice here," he said.

FAMILY AND FISHERMAN . . . As you drive south in the lower western corner of Montana, the country changes from the wide flat brown valleys between steep black mountains around Bozeman to the choppy, green timbered country of the Gallatin National Forest. A campground lies just off the road, deep in the mountain crotch cut by the tumbling Gallatin River. Here the sun comes late in the morning and drops early over the Spanish Peaks which rise to 10,000 feet, 11,000 on the west. It is an open grassy place, fringed with bushes and tall spruces and firs.

Two brown tents were pitched under the trees by the stream at one end. It was cool and quiet under the trees. The early afternoon sun made gold splashes on the pine needles on the ground, and the tops of the spruces showed silvery against the brilliant china blue and white sky.

Down at the other end of the campground stood another tent half in the sun, half in the trees. Here the bank was open, grass covered, and the river flattened out, running shallow over the rocks.

Two little girls sat playing on the bank. Nancy, the smaller, sat with her chubby short legs stuck out in front of her. Her bright-pink bathing suit was smudged in front where she occasionally wiped her hands. With one little finger she traced the slow path of a beetle in the dirt. Every now and then Joan covered it with dust and Nancy gurgled, watching the bug's frantic efforts to throw it off. Their neatly combed heads, each with a little hair ribbon, were bent in earnest observation. A few feet off their mother, Mrs. Walters, sat on a log sunning herself. Her full, plain face was flushed. Gingerly she felt her shoulders.

"Joan," she called, "Will you come put some of this sun-tan oil on my back?"

The child hopped up and went over to her mother. At the camp table nearby Ed Walters relaxed in the shade, a magazine propped up in front of him, a half-amused smile on his lips.

"There, that's enough." His wife took the bottle and screwed the top on thoughtfully.

"Swell article you oughta read in here," he told her. She smiled absentmindedly and went toward the tent.

"What you up to now?" he asked.

"We've got to have some meat for supper and I thought I'd send Mama a card. It's Saturday already, we've been here almost a week and I haven't written her once. How would you like some more of that hamburger for supper?"

"Yea, sure. Anything you get's okeh." He squinted his eyes at Nancy sitting in the bright sunlight. She looked up at him and dimpled. He went over and picked her up.

"You're a cute one," he said. "And you're gonna be 4 years old tomorrow. Hurray!" He set her down inside the tent.

"Someone needing a dress, mother, and maybe a clean face."

Now it was late afternoon, towards dusk. A fisherman moved upstream until he stood opposite them. He was a tall man, strong, lithe. His body leaned against the swiftly moving water. Walters and his children sat carefully on the edge of the bank on the grass watching absorbedly.

The fisherman worked easily. While they watched, he caught two fish. Each time he looked over at them sitting on the bank and waved. The children clapped their hands and hunched their shoulders. Then he lost his fly, so he ran in his reel and came over.

"Hello. My name's Carlson, Chris Carlson." He shook hands with Walters.

"How's that?" He showed the children the dozen trout in his basket.

"Me, I'm not much good at this fish catching myself," Walters said, and laughed apologetically. "You must be an expert."

Chris replied in a soft drawling voice. "Well, soon as spring comes along I git the itch so bad I can't set still. So I hit the road. I've fished pret' near everything 'tween here and Vegas."

"As a matter of fact," he went on, "my dad taught me to fish when I was a kid of 4 an' I've jest been fishin' ever since. Been up and down this stream 'bout 4 years now."

"You're lucky to be able to take so much time doing it," Walters said.

Chris scratched a match on the table and lit a cigarette. "Sellin'," he replied, looking over the match at Walters, his blue eyes steady, narrowed against the smoke. "Sellin' ladies' dresses and men's and ladies' suits. The trouble with us guys," he said, getting up, "is that as soon as we git some dough we jest have to lay off an' go fishin' or somethin' like that. We'd make more money than anyone else if we jest kept sellin'."

He hitched up his pants. "We've camped right down there; friend of mine an' his wife an' another guy. Those other two tents are ours." He pointed down the campground. "Come down an' see us," he said.

Chris sauntered down towards his camp. He remembered his fish and cut through to the shore. Down on the rocks another fisherman was cleaning his catch. He looked up when Chris walked toward him.

"Hello, there, you bum. Any luck?"

Chris showed him the 12 rainbows.

"Good. They'll be better eating than some of these. Let's get supper." He leaned over and picked up the fish.

Chris laughed and climbed up the bank. The other followed and they went along the path to their camp.

The sun had gone down but it was still light. After supper Chris took his rod and basket and went off to the stream. Up in the bend there was a place where the water ran deeper and quieter. Slowly he walked out. Nice, that first feel of water pushing on your legs; oughta get some good ones here.

Now down the river a woman has ceased for a while a visit with these friendly forest neighbors and herself was fishing fast water. The clouds were saffron colored, smoky on the edges. The water was black save where it caught the light of the sky and turned to liquid mercury and gold running on the surface. She liked this, being alone out here. She cast and recast far out over the water, smooth save where the eddies caught it and sucked it down in little swirls.

She felt the line tighten, then the reel sang out. The silver arc of a rainbow flashed. She played with it, bringing it in closer with each run and leaned down, scooping the trout in her net. Carefully she removed the hook and dropped the fish in the basket. Again the line whipped out and nicked the water. Slowly she took up the slack as it floated back toward her. Suddenly it stiffened. She braced herself quickly and let the reel spin.

"Gosh," she muttered, working hard to bring the fish in closer.

It was abreast of her now. She only could see it when it broke the water, leaping and bucking. The line pulled too taut. She let it out a bit, and the fish ran hard for the far shore. Suddenly the line went limp. All fishermen know that feeling, but she kept hoping as she wound in. Only the frayed leader swung out of the water, and somewhere among the dark rocks a rainbow nursed the fly.

She caught three more and then her luck ran out. The light was going over the mountains. You could hardly see the edges of the streams. Everything had grown fuzzy in the half light. She wound in the reel and snapped the lock. Then she picked her way across the stream. Down by the Walters' site she could see the council fire going and the children dancing around it and singing. Some of their friends had come out from Bozeman for the evening. She went over and joined the party; and the next day moved on.

A SINGLE LADY TAKING NOTES, she traveled on alone; and later, despairing of conveying direct human impressions without candid and forthright use of the first person singular, she wrote as a forest reporter to her Chief in Washington:

You know the St. Joe Forest of Northern Idaho. The camp sites run along one side of a broad grass field and the river swings out on the far side close to the trees. This has become a favorite picnic place for the farmers nearby and the mill hands of the Potlatch Lumber Company. About 30 log tables and stoves are scattered irregularly in the cool shade under the pines. I pitched camp here Saturday evening. The only other campers were a family from Potlatch at a site nearby.

Sunday I woke slowly. The sun was up and the mosquitoes were buzzing. I heard the deep rolling laughter of sturdy men and intermittent thuds of heavy objects dropping on the duff. I opened my eyes and looked around. My watch said only 5 o'clock. Not far away stood a big open truck and men, most of them very young, were unloading ice cream and beer kegs. Others were driving stakes.

"Look there, those folks may wanna sleep," one of them said. "Too bad. Guess they just can't!"

Low voices and laughter. They surely were enjoying being up at this early hour. They lit a fire in the camp stove near me and put on big kettles to boil. Sleep was impossible so I lazily watched them and looked up through the trees at the sky. Then I got up.

I went over to investigate the possibilities of getting some breakfast cooked on the crowded stove. I was met with great friendliness and the offer of anything they had.

"Don't know whether you like liquor or not, lady, but here's some if you care to sample it." One of them proffered a bottle. I politely refused and cooked my oatmeal and cocoa while they moved around me.

"We're putting up stands to hand out this beer and stuff at, an' there'll be hot dogs and sandwiches. Don't forget it, if you git hungry," one offered.

"You know the Potlatch Lumber Company?" another asked.

I nodded.

"Well, that's us. That is, the mill is divided up into divisions accordin' to what the work is an' there's a safety contest. Whatever division doesn't have an accident for 2 months gits 25 bucks. Us an' another division have gone 2 months now and we're just clubbin' together so's to have more stuff. Our families'll come out here for the day."

Another truck came in and stopped a way off. That was the other division. They started doing the same things that the first one had. They were all very friendly. I was just about to put on the eggs when I was confronted with a strawberry ice-cream cone. It was impossible in the face of such hospitality to refuse. They would not take no for an answer.

"Anything we have that you'd like, be sure an' ask fur it."

One of the men looked up from his work at me.

"You know, it's nice here. We play softball on the field out there."

More cars started to come. All day the cattle-guards at the entrance rang and the dust rose over the meadow until it hung like a yellow mist in the sunlight. The woods were alive with people. The kids started eating the minute they got there and ran circles around the picnickers. As the sun grew hot, people broke away and went swimming down the river.

They shifted about. Little groups formed here and there, then broke up and new groups formed. They walked about in two's and three's under the trees in the filtered sunshine, eating, talking, laughing noisily. The thick layer of pine needles muted footfalls. In three or four places men played horseshoes, slow and easy, punctuated with ribald jests.

"Hello, sister," I was greeted as I sat down on a log and watched a game.

"Lo."

"Your buddy left you all alone?"

I grinned, but decided not to say anything. He soon went ambling off with a pretty high school girl who blinked her eyes at him. People came and watched the game, then moved on. Adolescents moved about self-consciously on their long, young legs.

After lunch some of the energetic youths of my prebreakfast acquaintance organized games. They had prizes and they went around trying to herd everyone out on the field. Full of food and lazy in the midday heat, they were sluggish.

"Come on, everybody."

"Come on out to the field; we're gonna have some races."

"Here's your chance to show how good you are."

They drifted slowly out into the white sunlight. Already an improvised game of softball was going on in one corner.

There were relay races for 7- to 10-year-olds, boys, then girls. There were races for the older ones. There were three-legged races. There was a race for the women to sew buttons on the men's shirts. The final event was an old-fashioned tug-of-war, which nearly ended in a fight.

A lot of them went swimming again. The general tempo quieted down, fatigue encroached. The chocolate-smeared children were hauled off by their parents, some crying. Many were already asleep on the ground. Others flopped down where they were. Their limp, shapeless figures sprawled in the sun with the abandon of the sleeper. The sharp clink of horseshoes on metal stake rang under the trees.

As the sun tipped the trees in the west the campground came to life. The children woke up and started careening around. People got up stiffly from the ground. They stood around and yawned, slowly orienting themselves.

One by one cars started leaving for home. As the shadows grew long across the field, the crowd flattened out. People moved through the trees, wearily picking up scattered belongings. Slowly the dust settled in the twilight. Smoke rose from supper fires where some had decided to stay longer. Someone built a fire in the council ring. They sat around it and sang in the gathering darkness.

ANACONDA, the copper town, lies in a burnt, sweltering valley. The rows of paintless little houses that creep up the hill to the mill belie the bright activity of the main street. Towering over the city stands the giant smelter smokestack, belching yellow smoke over the bare, brown hills nearby. Saturday afternoon the streets are full of cars and people streaming down the hill from the mill. The air is hot and smells of acrid fumes from the plant.

Twenty miles to the west lies the Deerlodge National Forest, with Echo Lake and the cool recesses of the forest to which these people can escape. Many families drive out for picnicking and camping, but the majority of users are the young people who run up there for some fun and privacy in the out of doors.

The campground road makes a loop on the hill, circled by camp sites. There are more than a dozen sites here and they were almost filled. Sunlight was caught in the treetops, throwing green into the water. At one of the camp sites two girls, both young, had a fire going and some cooking pans standing by. They wore bathing suits. Their names, they said, were Jen and Sue. They were getting supper for "a coupla fellows," Jim and Bill, who were going to drive up to Deerlodge after their day's work in Anaconda. A third girl, named Bett, had brought Jen and Sue up in her car and was swimming. But Bett would be back. Harry, her fellow, was coming too.

"That's them," said Jen. A very old car, minus fenders, top, and rear seat, stalled at the bottom of the hill, by the lake. Two of the men got out and "rocked" her. "You have to do that; the starter just gets on dead center, or something, Jim says," said Jen.

The old car roared into life. The two men who had rocked her as one would rock a cradle if the cradle were big as a car and had rusty springs—piled in. Youth came roaring and snorting into camp to join the ladies. They drew up with a flourish, slammed on brakes, slid a little, and Jim, at the wheel, shouted:

"Get a load of that! Jen's picked a nutsy place right by the water. What ya cookin'?" He pushed an old slouch hat to the back of his head. Then, "Hi ya, gals! How ya fixed?" he drawled.

Jen looked up from the fire and grinned.

"Lo," she replied dispassionately and pushed brown curls out of her eyes.

"Where's Bett?" the biggest man of the three asked mildly. This was Harry.

"Swimming," said Sue. "See you there," said Harry. The men chugged the car over to the Boy Scout shack down the beach, to dress.

"Let's go," said Jen, "We can cook after dark." Leaving the fire to burn itself out on the open hearth and the half-cooked grub to cool, we went down to the swimming pier.

Bett was there. I was introduced. We sat and talked until the men came.

The purr of a motorboat drifted across the lake. We lay in our bathing suits on the dock. Bett complained:

"Gee, those kids are taking a long time."

Sue grunted and turned over. "These boards are gettin' into my bones. Wish they'd hurry."

Jen squinted her little nose and looked up at the sun. "Jim was cute last night, wasn't he?"

Sue cocked an eye up at her. "Thinkin' of marryin' him?"

"Naw, I'm not that crazy about any of the kids in town." She care fully observed a long crimson fingernail. "After school this year ma says I kin go to Salt Lake City an' learn to be a nurse. Then I dunno what'll happen." She sat down on the edge of the dock and put on her bathing cap. "I'm goin' in. Who's commin'?"

But then the men arrived. "Hi ya, kid!" . . . "Hello, there you mermaids!" . . . "Hello, yerself, an' what time do you think it is, anyway?"

"Well, here we are. Hold everything!"

"What a bunch of palookas," said Jen, scornfully, and yelped as Jim pinched her, then giggled and dove. He dove after her.

But I was the first one in. Six is company, seven a crowd. I figured that I had gone at this point as far as is proper in examination of the recreational attitudes of such decent, friendly, and bewildered youngsters. "See you later," I called and swam back to my camp.

The other two couples took quite a while at their kidding, rough housing, and loud talk before they too plunged into the stilled expanse of that beautiful lake and swam together quietly.

Next day was Sunday. Outside the girls' tent Jen, the first one up, gave a final stir to a smoldering can of beans, then stuck her head into the tent and hollered:

"Hey! the fellas want us to eat with 'em. Let's take the beans and tomatoes up. They got coffee."

She struggled with her straight hair in the small hand mirror.

"Nuts! Why wasn't I born with curly hair?" She put on a sweater. "Those guys oughta be dressed by now. Let's go up."

Sue got up sleepily and started to dress. "Me'n Bill had another battle last night," she said.

"What's eatin' Bill, anyway?" asked Jen. "Can't he stand his job?"

"Oh, the job's okeh. But it ain't getting us anywhere."

"You're telling me!" said Jen. "Come on; let's eat."

They swam again, twice, and hiked that day. The camp was full now. Every overnight site and every picnic table was taken. Night came on. The holiday crowd grew quiet, each little group busy around its own stove. Occasionally the rhythmic crack of a wood chopper snapped through the dusk. Then the stars came out and the boys and girls drifted down to the council fireplace on the beach.

Bill and Jim carried in driftwood.

"Say, Harry, this stuff's wet. Git that can of kerosene we washed the engine in. That'll make it go."

"Okeh. C'mon, Bett. Let's go." Bett leaped to her feet. She started. He rose and followed. Cries from the crowd at the council fire. One man cried, "Take it away, sister!"

Jen spoke more sternly: "Listen, you! Don't go into any clinches. We want that juice here before we freeze."

Everybody laughed. Bett looked up at Bill. The firelight accented the hollows at her cheekbones, the hollows under her eyes, marks of long hours at the mill. She cocked a saucy brow and winked. "Don't worry. We'll get your old kerosene."

Laughter rang out. They soon were back. The fire leaped high. Other campers drifted down to the warmth of the fire and the people.

Bill still was moody. He kept jumping up from Sue's side and piling more wood on the fire. Sue's eyes followed his every movement. She sought to reclaim him:

"Guess what, Bill?"

"What?"

"We brought the vie!"

"Say, that's somethin'. That's what we'll do. After this, we'll take it over to the Boy Scouts' shack and dance."

She nodded.

Someone started to sing: "I've been working on the railroad, all the live-long day." . . . Most of them took up the song. But Bill was silent and so was Sue. They sat on logs up front in the small council-fire amphitheater, close to the fire. The fire cast yellow light inside the foremost ring and a deep leaping shadow back from there. The families withdrew as the evening deepened. Children grew cold and cried to be taken in. Parents grew cold and were glad to creep under wool and canvas with their young. Only four of us, blanketed like Indians, remained at the council fire when Sue and Bill left it.

"Well, what are we sittin' here for?" Bill asked abruptly.

Sue put her hand on his arm. She told him in a whisper to "remember what we said."

He muttered something.

"Bill, don't be like that! Look, I got to finish school! I got to! This one year more and it'll be all over and then I'll get a job and we'll be all set."

"Sure, I know. You're all right, kid!" he said.

"Come on. Let's go in, Bill. It's cold out here. Come on. Let's go in and dance."

THE WESTERN Colorado mountains push up between the clear spruce rimmed lakes of the White River National Forest. A single road runs deep into the forest and dead-ends at Trappers' Lake. The road ends in a big turn-around ringed with camp sites.

I parked the car and got out. It was Sunday of Labor Day week end. There were many other cars parked here and all of the prepared camp sites were taken except one. I must have stood there looking around quite awhile when I was hailed:

"Hey there, young lady, kin I help you?"

I turned. An old-timer stood scratching his tousled white head and smiling. I walked over to where he stood.

"Can't make up my mind where to hang my tent."

He rubbed his hand down his bristly chin. "You be goin' to have trouble gittin' dry wood too. Hey ya got any with you?"

I shook my head.

"Well, I tell you what. See, I'm cookin' for these two guys from Denver. They're off fishin' now. You eat supper with us, then you won' have to think about wood. How's that?"

"Just the three of you?"

"Yep, an' don' worry about the other two; they'd be glad to hey you."

"Fine! I'll put the tent up over across the road there."

"Yeah, you do thet now, an' you come back when you're finished."

I put up the tent and got my bed out. The ground was covered with pine needles and my boots made little circles of water where I stepped. When I was finished, I went across the road to Steve, the old-timer.

"Here, Miss, will you stir this while I go git some more wood?"

People were still coming down the road from the lake. One couple, a man and his wife, stopped and talked to Steve about fishing.

"Nice folks," he said, coming back with the wood. "An ole fireman an' his wife from Salida, up here for a vacation."

We sat down at the table to peel potatoes. Steve went on. "He's got diabetes an's gotta by mighty careful. You oughta take a look at their tent, Miss. Nice little stove, big double bed, an' even a lantern. Snug as anything. They're not like those two camped down there next to you," he pointed. "I've been watchin' 'em an' they don' never seem to say much to each other. Jist act glum."

Every now and then someone coming back from the lake passed in the dusk and called "hello" to Steve. He got up and put the potatoes on the fire.

"Those guys oughta be commin' back soon. One of 'em's got a lot of money, Barney we call 'in. Al, the other one's jist a friend of his. They like to git away, but they don' like the dirty work so I come along an' pitch camp an' cook for 'em. You'll like Barney."

We could see the flickering light of the other fires around. A tall, heavy man pushed into the circle of light around our fire. It was Barney, and Al, slight and wiry, followed. They grinned at me and kidded Steve. Barney sat his big frame down on the bench and sighed; he was tired. He pulled his long rubber boots off slowly and his eyes twinkled at me across the fire. They hadn't had much luck fishing and were thinking of leaving in the morning.

"Thick as thieves up the stream at the head of the lake," said Al. "Catchin' each other's lines instead of fish."

I tried to find out what business Barney was in but he kidded me, saying that he was a sheepherder. I asked him how he liked roughing it in the woods.

"It's all right. This campin' racket, commin' out here 'n' sleeping, cold 'n' gettin' wet; just a way of gettin' a change. That's all it is. It's just something different."

Steve scowled over his coffee cup. "No life for an old guy like me, goin' on 74."

Barney smiled. "Not like the good old days when you were running the crack trains out of Denver, eh, Steve? He was the best engineer on the line, Miss."

"But we didn' have it soft like this when I was young. We took a train or a stage as far as it would go an' then packed in, where there weren't any dudes muckin' aroun'."

We washed up and the men sat around and smoked and talked awhile. Then Barney and Al went up to their tent to bed. Steve and I moved over and sat on some big logs by the fire. It was colder and quiet except for the wind in the pine tops and the stream falling close by.

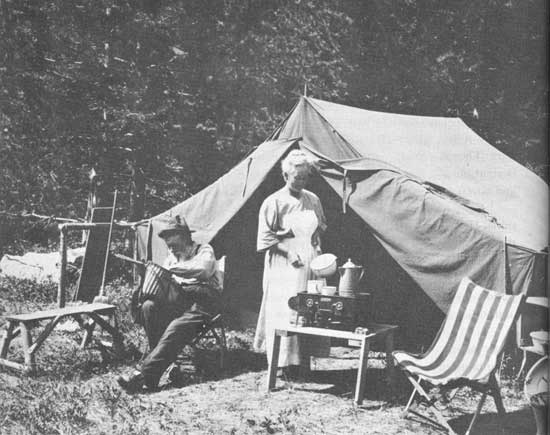

|

| You oughta take a look at their tent . . . Nice little stove, big double bed, an' even a lantern. Snug as everything. LEWIS AND CLARK NATIONAL FOREST, MONT. F-66691 |

"Nice, settin' aroun' a fire, ain't it?" He grinned at me and rubbed his hands near the blaze. "I like havin' women aroun', too. Gives ya nice feelin'. Lonely settin' aroun' alone." He looked through the branches up at the stars. They fascinated him. He talked awhile about the universes of stars beyond those we could see, about how there must be some plan for them all and how it gave him a religion. I asked him about Barney.

"Naw, he ain't no sheepherder. Never teched a sheep in his life, don' think. He's in business, made a pile of money. He's got what it takes to make the women look at him, too. Some guy. He's been married twice."

I felt sleepy and got up to go. He said to be sure and come over and use his fire again in the morning. I thanked him and left, feeling my way around the puddles in the road in the dark. The bed was warm and the night lay heavy and still.

MOST national-forest campgrounds are off the beaten track, deep in the mountains, but some lie close to the highways where the stream curves away or the road dips in a glade. These are unlike the other campgrounds. Here life is transient. This is but a brief stop on the way and one does not often get acquainted with one's neighbors. People slam in at 5 in the evening, pitch camp, eat and turn in, and are off pounding the roads at the crack of dawn.

There are a few like this on the road from Cody into Yellowstone National Park. I stopped at Pahaska campground, which lies in a bend of the north fork of the Shoshone. Cotton clouds towed their lumbering shadows over the mountains and all day the long yellow sightseeing buses from Cody churned the dust in their roaring climb.

The long strip of camp sites was deserted when I got there at 10:30 in the morning, except for a couple of temporarily abandoned trailers that looked like chickens standing on one leg with their eyes shut. The tall cottonwoods were silver in the sunlight.

Lunch time came and cars started dropping out of the stream on the road, dropping down to the quiet eddy of the campground—cars from Wyoming, cars from South Dakota, cars from Ohio, Nebraska, California. Another trailer came in. The people sat in tight little groups. If there were children, some of them wandered over to the water, but the minute lunch was over, they were whisked away in the car, back on the road; and once again I had the place to myself.

During the afternoon the owners of the deserted trailers came back. They had been sightseeing in the park. They sat around and talked and rested. They were at home on the road—time was their privilege.

From about 5 on, every now and then a car turned off the road and slipped down to the campground. Quickly they would pitch camp and eat supper. They were tired and quiet. A young German boy and girl from Boston camped on one side of me. They wore heavy boots and their bare, knobby knees stuck out under their shorts. On the other side were two couples from Ohio. They rolled out their blankets on the ground. If it had rained, they would have slept in their car. But it didn't rain although the lightning played in the mountains. Instead, the moon came out and made patterns under the trees and just before I fell asleep, I saw another car come in. The occupants ate quickly in the glare of their headlights, quietly, and turned in.

When I woke next morning, it was very early. The sun had not yet reached the valley. The mist spiraled over the stream. The Ohio people were leaving. The running engine of their car had wakened me. Others were stirring. I lay lazily, half awake, watching them pack up and leave. By 9:30 only the trailers were left and the German boy and girl. They were busy writing postcards on their log table. Then they left, too.

From coast to coast there are thousands like these, on the go. Some like to keep moving, they are restless; but there are others, too, who like to run away and be quiet in some bit of high, timbered land near the sky.

OTHERS . . . And so they come, these guests of our forests, in their thou sands and hundreds of thousands, and rest for awhile, most of them. Foresters sent afield not assigned especially to explore the joys, the troubles, the tangled life lines of the forest visitors (as the girl reporter just quoted was) wilderness to let down their back hair, as the saying goes, to relax, to impart.

No forester, whatever be his special mission afield to cruise timber, to audit staff accounts, to check equipment, to trail wood thieves, firebugs, fake "miners," game hogs, or to examine the effects of human ministrations upon returning forest cover no present-day forester, however specialized his training and interests, can entirely put out of mind the very human and pressing problem of natural recreation as he goes about his job today.

This, on the whole, has been an excellent thing for the Forest Service. Direct contact with the public on outings maintains a direct human approach. There are instances, even, of some of the most technical of foresters, out on specialized scientific research, accepting a friendly cup of coffee at a lone campfire and departing hours afterwards a little embarrassed at the thought of all they themselves contributed to the campfire confessional.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap3.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |