|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part Three

KEEPINGS THINGS NATURAL

Chapter Twelve

Game

The kings of England formerly had their forests to hold the king's game for sport or food, sometimes destroying villages to create or extend them; and I think they were impelled by a true instinct. Why should not we, who have renounced the king's authority, have our national preserves, where no villages need be destroyed, in which the bear and panther, and some even of the hunter race, may still exist, and not be "civilized off the face of the earth"—our own forests, not to hold the king's game merely, . . . but for inspiration and our own true recreation?

Henry D. Thoreau, The Maine Woods, 1864.

ZOO WITHOUT CAGES . . . The sight of a bear cuffing her cubs into hiding in the willows, the laugh of a loon on the lake at twilight, the whistle of the bull elk as he seeks his mate—these and a thousand other sights and sounds of the wild creatures enhance the charm of the forest. It is infinitely more pleasant to observe wildlife at large in natural surroundings than cooped or caged. The camera sportsman, the collector, the fisherman, the hunter, the Boy and Girl Scout, the Campfire Girl, the naturalist, the camper, and the sightseer each finds in forest wildlife a special interest, and often the transition from mere observations to a closer study gives one a new interest, a new source of enjoyment.

At first we thrill just to hear the slap of the flat, broad tail of the beaver as he dives from sight. Later, however, when we explore the home and the dam he has built, we discover that the beaver is a prime conservationist, storing water for dry periods, and flooding a willow swamp to insure food for himself. The moose feeds on the forage growth thus stimulated, and the deer or elk, too, when snow is deep. Noting this, we begin to gain some understanding of the interdependence of all forest life, animate and inanimate.

|

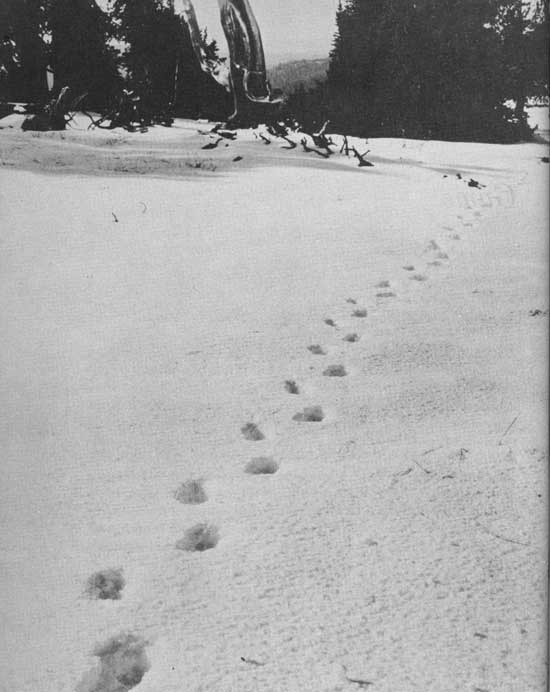

| The satisfaction of trailing game through the snow-covered forest. MULE DEER TRACKS, FREMONT NATIONAL FOREST, OREG. F-255237 |

Initial interest in deer may arise at the sight of them bounding gracefully away into a Wisconsin cedar swamp, white flags erect. As interest grows we find that in winter the deer "yard" in these same swamps. When the snow deepens, they feed on the reproduction and lower branches of the trees. If their number becomes excessive, the trees are trimmed as high as the deer can reach, the future forest is damaged, the deer's own food supply is destroyed, and with the next hard winter many will starve.

Even the plump and timid rabbit may seriously disturb normal forest development. On some forest plantations only half of the trees set out have survived because rabbits have nibbled the tender tops. In such ways as these, the necessity for maintaining a sane relationship between numbers of game and their food supply for critical periods is dramatized in the forest, so that all with eyes may see.

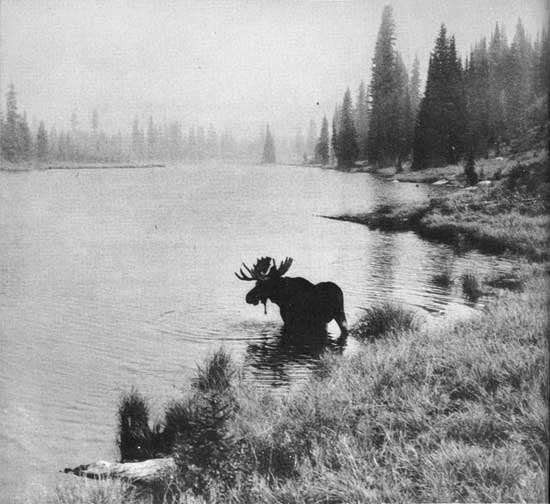

By studying ecology you become more conscious of all the stir and drama of wildlife. Ecology considers relationships between all things living and seeking a living naturally. You will learn to look for moose in the willow bottoms, elk in the meadows, and mule deer in rocky openings. In much the same way as fishermen know or think they know—the haunts of trout in a stream, the nature student learns the haunts of other living creatures. In many people the love for hunting or fishing as a sport is deeply rooted, and no other form of outdoor recreation will serve. The flash of a fish as it jumps for a moth or a fly, the exertion of wading a tumbling stream, the knowledge of trout feeding habits, the art of casting the line so that the fly drops on the water in just the right spot, the fight between man and fish as the line sings and the slim rod bends to the pull these, as well as the crisp trout for supper, are the things for which the sportsman strives. The big-game hunter wants to match his skill and stamina against the cunning, speed, and acute native sense of the wild things. He wants the satisfaction of knowing in advance where an elk will pass, of trailing the game through the snow-covered forest, of placing the shot in a vital spot, and of dressing out the kill with simple tools.

Not only do our national forests include most of the species usually found in a wildlife census; they also have many kinds of animals, birds, and fish not commonly known. The alligator, found in some rivers and bayous on the Choctawhatchee National Forest in Florida, is a fascinating creature. The condor, for whose preservation a special sanctuary has been proclaimed on Los Padres National Forest in California, is an almost extinct species of American vulture. The white-tailed Kaibab squirrel is found only north of the Colorado River on or near the Kaibab National Forest and Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona. The muskellunge, which once was found quite commonly in the waters of northern Wisconsin and Minnesota, has disappeared from many lakes but is now being restocked on national forests by fish planting, mainly in Wisconsin. On the Nantahala National Forest in North Carolina, and the Cherokee National Forest in Tennessee, and Los Padres National Forest in California are approximately 650 Russian wild boars introduced from Europe in 1910.

Among many other species, somewhat less rare but equally interesting, found on the national forests is the grizzly bear, once quite common in mountain and foothill areas of the West. This biggest of all bears in the continental United States has found competition with civilization particularly hard and has been reduced to less than 700 on the national forests.1 It has disappeared completely from the national forests of South Dakota, Nevada, California, and Oregon, and is fairly safe from extinction only in parts of Montana, Idaho, Alaska, and Wyoming.

1NOTE: A wildlife census table is appended on page 291.

Moose, the largest of the deer family, has responded to protection fairly well, and has gradually increased in numbers. This once-plentiful animal, which usually restricts its range to the vicinity of wet meadows and shallow lakes and feeds quite largely on aquatic or marsh vegetation, is found on national forests in Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, and Minnesota. The 1939 census of game on national forests reported more than 6,675 head.

The mountain goat always has sought the rough high mountains for its home. In spite of the rigorous conditions under which it lives, the mountain goat is steadily increasing. The 12,420 animals reported in the census are divided among the national forests of 4 States. Washington, Idaho, and Montana furnish the home for almost all of them, but surprisingly enough, there are a few in South Dakota, transplanted there years ago.

Bighorn sheep survive under conditions that make increase in numbers a problem. Fortunately, the present estimated 8,530 are distributed on 55 national forests. The wide distribution gives assurance against loss by epidemics.

The Roosevelt elk is another interesting species. Its original range probably covered a considerable part of the dense Pacific Coast forests and it is now found on 6 national forests in Oregon and in bands of various sizes in California and Washington, and in Alaska, where it was introduced; also there is a herd of 700 on Vancouver Island, B. C. Fortunately, this magnificent elk, with its remarkable protective coloring, is in little danger of extinction. It is estimated that there are close to 13,000 head at present.

|

| You will learn to look for moose in the bottoms. HOODOO LAKE, LOLO NATIONAL FOREST, IDAHO. F-314076 |

Other big-game animals found more plentifully on national forests are perhaps as interesting as any of these. To most city folk the sight of a deer or a black bear is as thrilling as the sight of a moose or mountain goat. These are present in large numbers on many forests, even though, because of their natural ability to keep out of sight, they may seldom be seen. At least one species of deer is found on each of the 161 national forests, elk are found on 95, antelope on 35, and black or brown bear on 134. The best available data, admittedly only approximately correct, indicate that nearly 1,784,000 nonpredators among the big-game animals (deer, elk, moose, antelope, mountain sheep, mountain goat, and bear) use the national forests of continental United States for at least part of each year.

The smaller fur bearers are equally interesting. One marvels at the ingenuity of the beaver in constructing their strong dams. McKinley Kantor's story of "Bugle Ann" dramatized in motion pictures, depicts a form of forest recreation that appeals to the many fox hunters who hunt but do not kill. The sleek, slim body of a mink or a weasel or marten brings delight at each rare glimpse. The hunt for 'coon in the moonlight is a sport that appeals to many. Thus, the 1-1/2 million fur bearers that inhabit the national forests are another wildlife resource of major importance to the forest visitor as well as to the trapper.

The so-called predators, most of which can also be called furbearers, are of special interest. The coyote slinking from sight into the brush on a hillside, or a quick glimpse of a wildcat, or a lynx, or mountain lion, is not soon to be forgotten. These animals, because they prey on domestic livestock or on other species of wildlife, are being reduced in numbers; yet they have a very definite place in game management and none of them should be exterminated. The wolves offer a real problem if their extinction is to be prevented. Obviously, they cannot be retained on ranges used by domestic livestock, but reasonable provision for their preservation elsewhere is desirable.

Upland birds and waterfowl are present in varying numbers according to locality and environment. The list includes band-tailed pigeons, many species of ducks and geese, several kinds of quail, mourning doves, several species of grouse, wild turkeys, and many others less well known to the hunter or the general public. The songbirds, hawks, owls, several kinds of jays, herons, the swan, and hundreds of other species inhabit national forests and deserve full consideration in the plans of management.

The fishing resource of the national forests consists of more than 70,000 miles of fishing streams and many thousands of natural and artificial lakes. The cold mountain lakes and clear, cold, fast-running streams of the West; the slower but important fishing streams of the Southern and Central States; the thousands of lakes and streams of the Lake States; the clear, cool brooks of New England all are represented on the national forests. They provide the necessary habitat for a wide variety of fish and an opportunity for millions to enjoy themselves.

|

| At least one species of deer is found on each of the 161 national forests. WHITE-TAILED DEER, OTTAWA NATIONAL FOREST, MICH. F-371800 |

DECLINE AND RESTORATION . . . Early American explorers and pioneers beheld a remarkable profusion of wildlife at Plymouth Rock and the other eastern ports-to-be. As they moved west and settled the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys, the Lake States, the Great Plains, and California, they found the same profusion. Only in parts of Utah and Nevada, the heavily timbered country of north Idaho and eastern Montana, and a few other places was any scarcity of game noted by the pioneers. Lewis and Clark recorded surprise at the abundance of wildlife in most of the country crossed by their expedition from St. Louis to the Pacific. The Hudson's Bay Co., the Astors, and others built great fortunes from the exploitation of wildlife in the early days.

But as the frontiers were pushed westward, civilization and settlement claimed for the plow and for domesticated livestock more and more of the new land—most of it the choicest range for some species of wildlife. Many species whose former habitat was on the plains, in low-lying valleys, or in the foothills were pushed back and yet farther back into higher and more inaccessible mountain regions of the West or into rougher or swampier or less fertile areas of the East. Always it was a retreat.

Fully 75 percent of the deer and elk of the West, in early times, was found principally on the plains and foothills. Now they roam high mountain country during part of the year. Bighorn sheep have not always as now made the high mountain fastness their sole abode. The despised coyote likewise was once primarily a plains animal. One of the exceptions is the antelope, which still persists as a plains animal although about one-fourth of the present population has taken to higher land. Thus during more than 300 years of American exploration and settlement, many big-game species have gradually been forced from their native range to a somewhat artificial habitat. Their new homes in the public forests, refuges, and parks or similar high country may be entirely satisfactory during the summer season, but they are seriously inadequate when the deep snows of winter cover the browse and other forage upon which the animals must feed.

In general, big game reached its lowest ebb in the West by the start of the twentieth century, when the greater number of the national forests were being created from the remaining public domain. Hunting for food, market, and economic purposes clothing, shelter, and articles of trade had largely ceased because of the general scarcity of game. Hunting for recreation, although in many places sharply limited by scarcity of wildlife, was becoming more popular.

The national-forest ranges at that period were satisfactory during the greater part of the year for the support of the big-game population at the time. Late spring, summer, and early fall range was plentiful. Even winter range, which is the most critical in the year-long cycle, and which generally was not to be found in the national forests, was usually adequate for the decreased game population. Only here and there at that time was lack of winter range serious.

But with more effective protection from hunters and predators established cooperatively by State and Federal Governments, and with wildlife given a definite place in the management of national forests, the numbers of most species of big game on national forests increased. Coincident with such increases was the gradual decline of adjacent winter range. Many valley bottoms were converted into cultivated fields, and the foothills came to be so completely used and often overgrazed by domestic livestock that little if any winter feed was left for game. On these unmanaged ranges outside the national forests, depletion of the forage proceeded rapidly to a point where the balance between summer and winter range, which with increases in numbers became more and more essential to wildlife, was destroyed. Thus, in the West, shortage of winter range in the foothills and on the adjacent plains much of the land is held in private ownership has become the controlling factor in determining the maximum numbers of most species of herbivorous game animals.

Reliable data as to the number of game on various western national forests at the time they were created and for several years thereafter are not available, but it is known that the game population trend of the first 10 or 15 years on most national forests was definitely upward. Beginning with 1924, methods used in taking the big-game census were greatly improved and it is known that, taken altogether, the big-game population on the western national forests has almost trebled since. In spite of general open hunting seasons for deer and extensions of hunting season in the elk country, deer have increased 190 percent and elk have increased almost 160 percent in the last 15 years. Bighorn sheep and grizzly bear are the only two species that have shown a decrease. These significant over-all increases on national forests, though made up in some instances of increases on areas already overstocked, are in sharp contrast to actual decreases on some other areas, and illustrate how these animals respond to the better protection and management given them during recent years.

On much national-forest land and in the summer, more big game than is now present could be cared for. This is especially true in the Ohio Valley, in the Ozark Mountains of Missouri and Arkansas, and in other parts of the South.

Overstocking of deer on parts of the Huron and Manistee National Forests in Michigan; the Nicolet and Chequamegon National Forests in Wisconsin; the Malheur in Oregon; the Fishlake and Dixie in Utah; the Allegheny in Pennsylvania; the Pisgah in North Carolina; and the Modoc and Lassen in California is a result solely of shortage of winter forage. Similarly the elk population exceeds the feed supply during the critical winter periods on parts of the Clearwater National Forest in Idaho; the Lewis and Clark, Flathead, and Absaroka in Montana; Olympic in Washington; the Umatilla and Whitman in Oregon; the Teton and Wyoming in Wyoming; and the Targhee in Idaho. But even if additional areas of winter range for wild game were acquired, present conditions might easily be repeated unless a control of the maximum numbers allowed on the range is maintained. No well-managed domestic herd is allowed to increase beyond its feed supply, and the same principal is applicable to wild game, especially to deer and elk.

The first steps to halt the downward trend in numbers of almost all species of wildlife were the State game laws to establish seasons, fix bag limits, and provide bounties for the taking of predators, and the creation of control and law-enforcement bodies under various forms. Another development was the establishment of refuges and sanctuaries by State and Federal Governments. Game animals, fur bearers, game birds, and fish have been transplanted in depleted areas or streams, and the propagation of planting stock at game farms, fish hatcheries, and rearing ponds has become an established practice. But perhaps most vital of all has been the development of a public sentiment favorable to wildlife conservation.

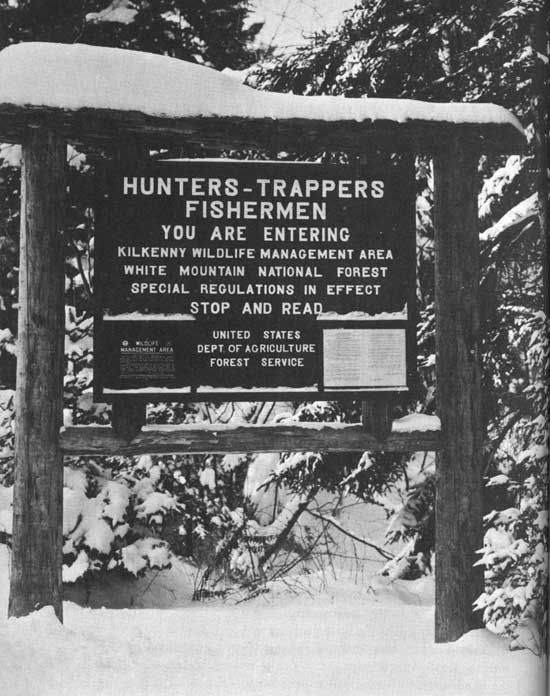

In almost all States containing national forests, resident forest officers are ex officio State game wardens serving without pay. Even where this is not the case, it is a recognized duty of every Forest Service officer to report violations of game laws and assist in law enforcement if such assistance is desired.

REFUGES established by States within national forests in 26 States now total more than 23 million acres. Federal refuges inside national forests in 13 States and Alaska total nearly 612 million acres, and some 7 million additional acres of national-forest land are handled as game refuges through administrative restrictions by the Forest Service. Of this 36-1/2 million acres, less than half is used by domestic livestock. Both within refuges and without, the numbers of domestic livestock and of game have been found or should be adjusted to meet the carrying capacity of the range.

In much the same way, help has been extended in rebuilding the fish population. With the cooperation of the States and the United States Bureau of Fisheries, rearing ponds and fish hatcheries have been constructed on national forest land. In most instances these are being operated by the Bureau of Fisheries. Many miles of streams have been developed to improve the habitat for fish. Lakes have been covered with fish-habitat surveys and in many instances have been developed. In 1938 the Forest Service planted more than 180 million fish in national-forest waters, along with an even greater number planted by States and other agencies.

With the help of other agencies, game has been moved from overstocked to understocked range. Deer have been moved from Wisconsin and Michigan to the Ozark Mountains in Missouri. Beaver have been taken from Michigan and planted in the streams of southern Illinois. Elk plantings have been made on many national forests, among which are the Weiser and Cache National Forests in Idaho, the Sitgreaves in Arizona, the Wasatch and Fishlake in Utah, and nine national forests in Colorado. Surpluses of mule deer on the Kaibab National Forest of Arizona and white-tailed deer on the Pisgah National Forest in North Carolina have been trapped and liberated in other areas where these species had disappeared or were very scarce. Bighorn sheep have been imported from Canada and turned loose on the national forests of Wyoming. Wild turkeys, quail, and other game-bird species have been reintroduced on ranges from which they had disappeared. Such efforts at artificial restocking cannot be substituted for effective resource management as a method for increasing wildlife populations, but they do have a place in handling the wildlife resource.

PRINCIPLES OF MANAGEMENT, in the final analysis, start with and are limited by the possibilities for managing the wildlife's environment. Too often wildlife has been thought of as something separate and apart from land, rather than as one of the crops. Too often, also, public interest and game laws have centered on maximum numbers, rather than on relating numbers to the food supply available for the year-round support of the species. Thus, temporary increases, rather than sustained annual yields of wildlife have been built up, only to be wiped out by an unusually hard winter, by disease, or by actual destruction of the habitat through too heavy use.

Protection from predators and man, artificial restocking, feeding, and other similar measures are all important aids to management, but without a favorable environment wildlife must decline. The planting of millions of fish in streams and lakes is of little avail if the natural habitat has already been destroyed by pollution of the waters, by silting over of spawning beds, or by destruction of the natural food supplies. Pheasants and quail may be introduced but they will gradually disappear again if food, shelter, and climate do not meet their needs. Woodpeckers may decrease with the elimination of dead trees and snags from the forest. Migratory waterfowl may travel the flyways unmolested by hunters; but destroy their nesting grounds by fire or overgrazing, drain the shallow lakes and marshes upon which they rest or feed, pollute the waters which they use, and their numbers will decline. Clearly, environment is the major factor in wildlife management.

Much of the history of wildlife is a record of temporary relief measures to correct an abuse without adequately attacking the broad problem. Experience has taught game administrators that such provisions as the buck law, game refuges, bag limits, and closed seasons, may be good or bad depending on the time and place. The bounty system may lead to the destruction of predators which have a very definite place in management. All such provisions are merely implements that have been used in an effort to correct unsatisfactory conditions, and they have been too long regarded as permanent management practices. The bad condition of many wildlife ranges today is largely the result of dependence on such corrective measures. Legal limitations on hunting may result in overstocking and partial destruction of the habitat; legal stimulus to killing, as exemplified in the bounty system, may lead towards extermination of the predators and consequent overstocking of the species on which the predators formerly preyed.

Efforts to remove surplus game by trapping have proved hopelessly inadequate. Outright slaughter is both abhorrent and ineffective in dealing with large surpluses. Some progress has been made with regulated kills by modification of the hunting season, etc., but nowhere yet has the principle of treating wildlife as a renewable crop to be held to the food capacity of the "farm" been given full effective use.

Grazing by domestic livestock, production and use of the timber, and use of the water resources for domestic or industrial purposes, all—on the national forests must be coordinated with the needs of wildlife. In some areas, use of game and domestic livestock compete for earth room and sustenance. In this the national forests of the East are not involved because open range grazing by domestic stock is not commonly practiced. Likewise in the West there are more than 46 million acres of national-forest land which because of cover types, roughness of topography, lack of forage, lack of water, or inaccessibility, are not usable by domestic livestock. To this must be added nearly 6 million acres of usable grazing land set aside in virgin, botanical, wilderness, and wild areas where domestic livestock are not permitted. Much of this area is admirably suited to game use.

On lands properly grazed by livestock, there is ordinarily abundant cover and sufficient forage to maintain a reasonable stocking of wildlife. Here competition is minimized by the fact that different classes of livestock and different species of game normally feed on different types of vegetation. But on areas such as the ranges adjacent to Yellowstone Park, competition between game and domestic livestock for forage gives rise to sharp conflicts. Upon most national forests such problems are not unsurmountable if the desires and needs of the various interests are given full consideration and there is maintained a fair attitude of give and take.

Conflicts between wildlife and timber use are relatively easy to solve once the problem is correctly understood. Although any timberland will support wildlife of some kind, not all timberlands are suited to the reproduction of big game. In places the timber cover is so dense that herbivorous game animals can find little feed. On other areas the cover may have been completely destroyed by fire, and reforestation by planting may be required. Here the rabbit population may become so heavy that active control measures are essential for a few years if the forest is to be restored. In other instances, the winter deer population may be so heavy in cedar swamps that the reproduction will all be eaten and both the future forest and the game-food supply jeopardized. Here again control of numbers is indicated.

Timber harvesting, on the other hand, if carried on without regard to the needs of wildlife, may be detrimental to the habitat. On the other hand, cut-over areas, if properly handled, provide a more favorable food supply for wildlife than many virgin areas. To assure this, timber-cutting operations have been modified where necessary to increase the forage supply. In the eastern national forests, cutting methods have been changed to favor certain kinds of trees and shrubs that provide food for different species of wildlife, with good results. Also by leaving a number of hollow or defective trees, nesting places for birds and homes for squirrels, raccoons, and so on, have been increased. In artificial-reforestation plans for large areas, a portion of the area is left unplanted in order to improve the future habitat for game. Tree and shrub species valuable for game food and cover are being grown in some forest nurseries for transplanting to favorable sites to improve the habitat.

Similarly, the needs of wildlife must be considered in any plan to manipulate water levels or change the use of water on the national forests. Illustrative of this is the adverse effect on fish population when a sawmill discharges sawdust into a stream. The raising of water levels by water storage, as has been stated, may destroy feeding and nesting grounds for migratory waterfowl. The straightening of a stream channel through a wet meadow may reduce the cost of construction or maintenance of a road, but at the same time by more effective drainage it may destroy the habitat for beaver.

On the other hand, a small dam to raise water levels or create a new lake may provide just the conditions needed for migratory waterfowl or form a new habitat for fish. Springs developed primarily for domestic livestock may at the same time open up new range for big game or upland birds.

A MIGRANT YIELD, the wildlife crop must be managed as a cooperative undertaking. Although it is true that wildlife is one product of the forest, it is not a stationary product. It moves from place to place according to habits of the individual species. It is on public land today and on private land tomorrow. Some species summer on the national forests and move to the adjacent low-lying private land in winter. The migratory fowl may nest in the Chippewa National Forest in Minnesota, and winter on some private estate in Florida. Private, County, State, and Federal land may all be used even by an individual animal.

The multiple-use plan of management in effect on the national forests recognizes and provides for wildlife as a major resource, in providing for game range and the improvement of the wildlife food supply and habitat. Conflicts between wildlife and other forest uses are adjusted in accordance with social, economic, and biological principles. Provision is made for temporary or permanent refuges where needed. Surveys and studies are made to determine carrying capacity of the ranges, the existing population, and the effect of changes in population on the carrying capacity.

The States, on the other hand, make and administer most of the laws relating to use and protection of the animals themselves. Migratory waterfowl is, of course, a partial exception. Among those laws are measures prescribing bag limits, sex or size of game or fish which may be taken, open and closed seasons for each species, designation of closed areas, bounties to be paid for taking predatory animals, and many other details.

Thus the management of game or fish and of the land or water which forms their habitat are in part divided. On one hand are restrictive laws which are essential tools to management, enacted and enforced by the States; and on the other is the management by the Forest Service of a large part of the environment so as to give the maximum contribution of wildlife in the light of other legitimate uses of the land. As part of the management of the environment it is clear that the Forest Service must retain the right to protect the property from damage by wildlife.

Under the division of authority, the closest kind of cooperation is indispensable. In certain States there are detailed formal agreements that are, in effect, cooperative management plans. In other States less formal but progressively satisfactory arrangements are in effect with the constituted State authorities. In some States, dependence on inflexible and restrictive State laws rather than on broad authority vested in a strong responsible game and fish department makes difficult or virtually impossible any adequate joint approach to wildlife management.

But the States and the Forest Service are not the only agencies charged with responsibility for wildlife. The Biological Survey long has been the primary Federal research agency in this field. Here again, cooperation is essential and has been effected. A formal agreement between the Biological Survey and the Forest Service defines the responsibilities of each in a way that is mutually satisfactory. Briefly, the Biological Survey is the responsible wildlife research agency of the Federal Government and advises on questions related to the research field. The Forest Service is responsible directly for administration and management of wildlife resources on the national forests, and advises and assists in the solution of wildlife research problems.

|

| The Forest Service manages a large portion of this country's wildlife environment. WHITE MOUNTAIN NATIONAL FOREST, N. H. F-373391 |

The Bureau of Fisheries likewise shares responsibility. The fullest cooperation has been extended by that Bureau in the development and execution of plans for improving fish habitats and population. Detailed plans for fish hatcheries and rearing ponds have been prepared or reviewed. Advice as to the suitability of streams or lakes for different species of fish has been given. Also, millions of fish, with the approval of the States involved, have been turned over to the Forest Service from Bureau of Fisheries hatcheries for liberation in national-forest waters.

Effective cooperation in common wildlife problems has also been worked out between the National Park Service and the Forest Service. This is especially important in the West where many of the national parks either join or are surrounded by national forests and where complete protection within the parks may result in building up populations in excess of the carrying capacity of available winter range. Special mention should be made of the elk situation surrounding Yellowstone National Park where the National Park Service, the Forest Service and the Biological Survey, the States involved, and other interested agencies have sought the solution of an aggravated winter-range problem through buying up privately owned winter range, directing hunting during the period of migration from summer to winter range, and providing hay for the animals when snow conditions are too unfavorable.

Various semipublic organizations such as the American Wildlife Institute, the Izaak Walton League, National Association of Audubon Societies, the hundreds of sportsmen and game associations, and many others have shared in the progress. Private landowners often have permitted the use of their property by wildlife at considerable cost and inconvenience to themselves. The tremendous increase in public interest in wildlife during the last 25 years has been reflected in improved legislation, both National and State, and in increased financial provisions for fish and game management and research. There is now general recognition that wildlife, in the present status of our social, economic, and industrial development, can no longer shift for itself. It has become a major problem for study and guidance and organized administration on a common-sense basis.

A CONFLICT OF INTERESTS between sportsmen and those who dislike killing anything was noted in chapter 1. Much energy and emotion is wasted by high-pitched contention; much remains to be done to harmonize the attitudes of various wildlife groups. One group places complete reliance on restrictive legislation; it wants nothing killed and would remove man's influence entirely from the wildlife picture and restore what they call Nature's balance. Others confine their interest to special groups such as songbirds, or hawks and owls, or predators, or some other important sector of the entire wildlife population, each seeing in the preservation of its particular interest the solution of the whole problem. Some of these demand that the rest of the animal kingdom be subservient to the needs of the class in which they are interested. Certain trout fishermen want all otter and all fish-eating birds exterminated. There are sportsmen who see only the game and do not recognize the need of food and cover, and fox hunters who want no foxes killed no matter how detrimental they are to upland birds.

Much of the difficulty in applying sound principles has come from a failure of the friends of wildlife to see eye to eye as to methods. But public attention now is focused on the problem; more wildlife administrators are stressing management of the environment; and these things can result only in fuller public understanding of the problem as a whole. An increasing and intelligent interest of the millions of forest visitors sportsmen, campers, boy and girl adventurers, and picnickers—in the wildlife they see or hear on a trip to the woods will have a tremendous influence on the wildlife policies of the future.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap12.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |