|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part Three

KEEPINGS THINGS NATURAL

Chapter Eleven

Water

They shall turn the rivers far away; the brooks of defense shall be emptied and dried up; . . . and everything sown by the brooks shall wither.

Isaiah 19, 6-7.

"TO RULE THE MOUNTAIN is to rule the river, is a Chinese proverb more than 40 centuries old. And: "Mountains exhausted of forests are washed bare by torrents," the ancient Chinese said.

Early in the present century Gifford Pinchot was shown before-and-after pictures of denudation and erosion in North China. The Chinese knew enough, it seems, to handle their land wisely; but they had not, as a people working under various pressures, been able to apply their wisdom. For here was a painting done in the fifteenth century, and here were photographs of the same scene taken in the twentieth century, some 500 years later. "The painting," Walter C. Lowdermilk recalls, "showed a beautiful, populous and prosperous well-watered valley at the foot of forested mountains." But he also recalls that "the photographs showed the mountains treeless, glaring, and sterile; the stream bed empty and dry; boulders and rocks from the mountains covering the fertile valley lands. The depopulated city had fallen in ruins."

|

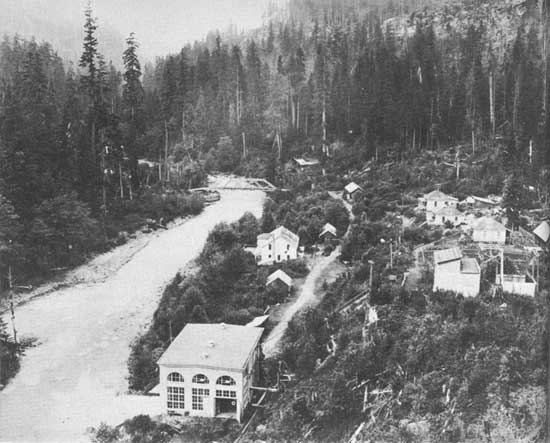

| When the men who came there to do business got there first. NORTH FORK NOOKSACK RIVER, MOUNT BAKER NATIONAL FOREST, WASH. F-30573 A |

Gifford Pinchot took the pictures around to the White House and showed them to Theodore Roosevelt. President Roosevelt illustrated his message to Congress with those pictures and as a result the United States Forest Service was established.

Men grown gray in the Service recall that Pinchot, their first chief, showed the same pictures before congressional committees. Also, to drive home the role of cover in staying run-off, he carried to the hearings a plank, a blanket, and a pitcher of water. Slanting the board, he poured water upon it, and immediately upon the floor below he had a flood. Then he covered the board with the blanket and again poured water, and this time the water soaked in and seeped down slowly.

The new-born Forest Service, dating from 1905, set out to make the American public erosion conscious at the time when most soil scientists even in the Department of Agriculture, refused to believe in the menace or give credence to the warnings. Hugh Bennett in the Bureau of Soils at the time (he is Chief of the Soil Conservation Service now) already had raised his voice, crying warning especially against sheet erosion on farm land. But few believed him. The loss continued. Sheet erosion strips off tilled topsoil evenly, grain by grain, layer by layer, stealthily. It may leave no gullies, but it makes the soil thinner, poorer, all the time. Foresters did not know much about sheet erosion. It is rare in forests, but plain evidence was available even then that veritable avalanches of soil-wash and rock-wash from denuded high plains and mountains were bringing unutterable havoc upon the country below. So the foresters cried havoc; and with all the force of his vibrant voice and character, their great friend in the White House, Theodore Roosevelt, echoed the cry.

"To skin and exhaust the land," he proclaimed in 1907, "will result in undermining the days of our children, the very prosperity which we ought by right to hand down to them amplified and developed."

In 1908 President Roosevelt called a conference of Governors at the White House, to forward conservation. Dr. Thomas C. Chamberlin, a geologist at the University of Chicago, was there to talk to the governors and, through the press, to all the people.

"Soil production," he told them, "is very slow. I should be unwilling to name a mean rate of soil formation greater than 1 foot in 10,000 years. In the Orient there are large tracts almost absolutely bare of soil, on which stand ruins implying former flourishing populations. Other long-tilled lands bear similar testimony. It must be noted that more than loss of fertility is here menaced. It is the loss of the soil body itself, a loss almost beyond repair. When our soils are gone, we, too, must go unless we shall find some way to feed on raw rock, or its equivalent. . . .

"The key lies in due control of the water which falls on each acre . . . The highest crop values will usually be secured where the soil is made to absorb as much rainfall and snowfall as practicable. . . . This gives a minimum of wash to foul the streams, to spread over the bottom lands, to choke the reservoirs, to waste the water power, and to bar up the navigable rivers. The solution of the problem . . . essentially solves the whole train of problems running from farm to river and from crop production to navigation."

CLEAN WATER has been a primary product of our national forests from the first. The economic uses of water rising in or flowing from the forests—water for municipal supplies, irrigation, power, mining sometimes goes along harmoniously with use of the same water for recreation, but sometimes economic and recreation uses clash. Time was, of course, when our mountain headwaters were untouched by industry. The industrial use of water started in the bottoms. Then, as water sources became more put upon and injured, clusters of industrial structures climbed the streams. As these businesses clambered upstream, water was increasingly diverted, larger and more sprawling structures arose, and the landscape was altered, sometimes tragically, over wide areas.

If dams and power sites are designed and conducted by their owners with some thought of the rights of those who seek values from the forest other than power or salable products, the necessary conflicts between the industrial use of water and its recreational use are few. But when businessmen got there first in our industrial era and reared structures starkly utilitarian, and when they still insist such structures are more beautiful and rewarding than trees and untrammelled streams, then the conflict between a desire of business for stripped-down "improvements" and a popular impulse to return to the shelter of trees still living soon becomes plain.

Many industrial plants now operating on the forests display, in their clearings, and in the arrangement and architecture of their structures, an utter and arrogant disregard of good planning, and of decent landscape principles. Such stark designs may look all right as part of the urban pageant of man's mighty progress on a wholly denuded mountainside out from, say, Pittsburgh. But they do not look at all right on our remaining forest land.

Compromises seem possible, without irrevocable loss. Business promoters, rural and urban, can have their power and products out of many mountain waters more quietly, without messing up what is left of our forest background. But first they must slow down a little in their driving stride, consult their own deepest interests and impulses, and listen to reason.

Business is business. Agreed. But ugliness is needless. It is generally possible to fit dams, powerhouses, and even transmission lines into the forest landscape without a widespread effect of disharmony, if care is taken in the landscaping; and if tree and shrub planting to screen and to tie structures into the landscape is undertaken immediately following the construction job. There is seldom need for any forest-industrial development spreading its structures, its construction scars, and other evidences of its being over a great acreage. Yet some industrial outfits persist in sprawling out in the public woods like giants barring use of the woods to the people. And some big operators persist in practices that are boorish, mean, and stupid.

Conflicts between private business and public pleasures that are the most difficult to adjust arise, as a rule, in places where exclusive rights or privileges were granted prior to the establishment of the national forests, or before the present surge favored simple outdoor recreation. The standard factory sign, "Keep Out Except on Business," does not appear on national forest areas so preempted, but the attitude of old-time operators toward the public who own these preempted parts of national forests remains, all too often, precisely that; and such operators show it in their operations.

They flood land without bothering to clear it of trees. The snags and debris under such water render it useless or dangerous for boating or swimming.

They manipulate actual water—shift actual water levels so abruptly as to throw out of adjustment natural communities of shore-line life, ranging from algae to man. And sometimes, in headlong conflict over rights, business operators have been known to exert such a drain as, in effect, to steal a lake and all the fish in it. They drain that lake, and all that lives in it and by it, right off our map and out of our future.

Such rugged practices show signs of abating. Even the most intrenched and resolute of old-timers are responding somewhat to a public resentment each year more effectively expressed. Newer companies, out to make power or plastics or some other product of the woods and streams, incline now to ask how they can do business there without leaving the scene of their operations naked and barren.

The more enlightened concerns refrain from so raising or lowering actual water levels as to flood or drain, unnecessarily, forest pleasure grounds. And, once company reservoirs are established, they try to maintain a pleasant vacation environment by timing the use of water. Often they find it possible to time the heaviest draw-down with the lightest period of public recreational use. Thus they avoid revealing unsightly mudflats and debris-covered shores at the height of the vacation season when most people seek the woods and shores for beauty and consolation.

Not all companies are so considerate. Many a camping and picnic spot has been made useless or unattractive just at the time when the people needed it most. Later, after Labor Day, someone in the powerhouse may be told to throw the switch and restore the lake when few or none are there to share it.

SLUDGE AND POISON . . . Sludge from hydraulic and other mining operations on the forests, and pollution of the waters with manufacturing wastes, also maim or destroy woodland values. Here, again, the destruction is for the most part preventable.

Operators under permit in national forests can be required to install settling basins at their own expense. When operations are situated on private lands, however, the settling basins, if installed at all, may have to be constructed by the Government on national forest lands below the point of water use. Such installations now are made at public expense only if the recreational values so protected justify, and if no means exist under State laws or otherwise to enforce some other decent compromise for the moment.

It is generally possible to remove industrial waste, such as the residue of tanning and pulp industries, before discharging waste water into natural streams. Sewage disposal plants are also practicable. If damaging waste substances are eliminated from natural streams, the waterways retain their attractiveness and safety for camping and swimming, and fish are not poisoned.

In this day of chemical and engineering enlightenment, mankind does not have to destroy beauty, poison water, kill fish, and spread disease in order to have cities and factories. A special report, Water Pollution in the United States, submitted to the President by the National Resources Committee early in 1939, goes into these troubles, and the necessary cures, in detail, State by State.

Progress has been made, the committee finds, even since 1910, but, "in order to abate the most objectional pollution" within the next decade or two, an expenditure of at least 2 billion dollars will be necessary. Since most of the pollution comes from municipal sewage and some factory waste, the responsibility for the expenditure must fall largely on city governments and private concerns, "supplemented, perhaps," wrote President F. D. Roosevelt, reviewing the report in a foreword, "by a system of Federal grants-in-aid and loans organized with due regard for the integrated use of water resources and for a balanced Federal program for public works of all types."

Considering the constant contamination of water by towns with inadequate sewage systems, and the constant pollution of water by industrial wastes, the problem of keeping an increasing swarm of picnickers, campers, and tourists on the national forests from befouling water sources seems relatively slight.

Signs and instructions that stress the most elementary laws of sanitation, simple outdoor toilets and incinerators, and an indicated supply of drinking water known to be safe—these, in most places, are "improvements" enough. By such simple devices it has thus far been possible to admit millions of persons to enjoy the national forests with no widespread contamination and no evidence of serious pollution as yet.

WATER FOR PLEASURE . . . Man's oldest instincts draw him to the seashore, riverbank, and stream side. Few cities located far from surface water have grown from camps or settlements. Few campers, now as in the past, choose sites remote from water, if water is available. The flash and lap and tinkle of live water in sea or brook adds to the charm and serenity of the site, and gives the camper more quiet things to do: Fish, swim, boat, wade, or perhaps just to sit there and gaze into limpid coolness. Of all the recreational resources of the national forests, water is surely the most valuable.

Of water most of the national forests still have plenty. A glance at a map of Minnesota and Wisconsin forests, for instance, discloses countless lakes and a veinlike network of thousands of small streams feeding successively larger and larger ones to form rivers. So it is even on drier forests westward. Four of the largest drainage systems of the country originate in the national forests of Colorado. To the northeast too, countless streams cascade down the slopes of the White Mountains.

In some of the Central States, in the Black Hills of South Dakota, and throughout the Southwest in general, natural water is not so abundant, or such as occurs naturally is not always useful for recreation. It is likely to be stilled and stagnant. Even where there is some flowing fresh water as in parts of the South, urban pollution often makes it unusable. Such forest areas face a real problem in developing and maintaining watering places for the public use and pleasure.

Then, too, much water on the national forests in general is no longer freely available to pleasure seekers, and public demand upon it increases rapidly. To help prevent pollution of drinking water, certain watersheds have been closed to recreational use. And the demand keeps rising to bar the general public from easy access to many lakes and streams. Private ownership of a key tract strategically situated may discourage or even prevent large numbers of people from finding and using for their pleasure the water and shore sites.

Despite all this, and despite other conflicts between the few and the many which have been suggested, much good water in the national forests still is open to the use of the people. And here and there, through recent land acquisitions and public construction, the amount of clean water useful for pleasure has been increased.

Some of the forest pools developed cost less than $200. The construction is simple: A low dam of unobtrusive design, to deepen and perpetuate an existing swimming hole. To clear snags, rocks, and brush away is sometimes enough. But clay beaches, or silt beaches, are a bit miry. It is hard to swim and bask and come out clean. With relief labor it is often possible to truck in some sand, cheaply, and make a small clean beach by a clean pool or lake in the public forests.

|

| A low dam of unobtrusive design, to deepen and perpetuate an existing swimming hole. BLUE BEND FOREST CAMP, MONONGAHELA NATIONAL FOREST, W. VA. F-325774 |

The job becomes more expensive in drier climates where springs must be found and tapped to augment inflow. Sometimes the compromise works down to a wading pool for the youngsters. But even that is something to sit by and enjoy, if you are older, in hot, dry parts of the country.

Under pressure of an all but frantic demand and a quickly increasing use, many pleasure-water developments at forest camps and picnic spots have been pushed already beyond simple and sylvan proportions. This was sufficiently indicated in chapter 6. But no other pleasure development on the national forests has proved such a boon or aroused such universal approval, in terms of use, as the creation of lakes and pools in the dry or lakeless sections.

Consider, for example, a small lake development in a generally lakeless region: Cave Mountain, on the Jefferson National Forest, in Virginia. It is a made lake of 7 acres, with a neat, made crescent of sandy beach, and picnic sets ranged 'round about, under trees. On holidays this simple equipment provides recreation for more than 2,000 visitors. Again:

St. Charles dam in the San Isabel National Forest in southern Colorado is 90 feet high and 600 feet long. That begins to run into money. But this dam impounds a lake 35 acres in extent. It makes a forest lake that is available to a great prairie population and they throng eagerly to relax there during the long, hot summers.

Tensleep Dam on the Bighorn National Forest in Wyoming is only 26 feet high, but it creates a 274-acre lake in a generally lakeless region. Bismarck Dam on the Harney National Forest in the Black Hills of South Dakota produced a lake of 23 acres in a locality where recreational use is intense and water scarce, either for use or pleasure. Vesuvius Dam on the Wayne National Forest in southern Ohio, Shores Lake development on the Ozark National Forest in Arkansas, Pounds Hollow Dam on the Shawnee National Forest in Illinois—all are new midwestern watering places of the people.

Here and there, business interests have not only ceased to hinder, but have stepped in to help keep public watering places and the surrounding terrain as natural as possible. Thousands, for example, take advantage during summer heat of improvements developed at Lake Rabun, a large power lake on the Chattahoochee National Forest in the mountains of North Georgia. Here, with the cooperation of the power company, an attractive portion of the shore line has been developed for public use by the installation of a sand beach, boat dock, diving raft, and other facilities. The lake, which is 17 miles long, is clean and lovely, suited for purposes of restful contemplation, or for swimming, or boating, or fishing. Since it is one lake in a series of four, the water level is maintained without difficulty during the recreational-use period.

|

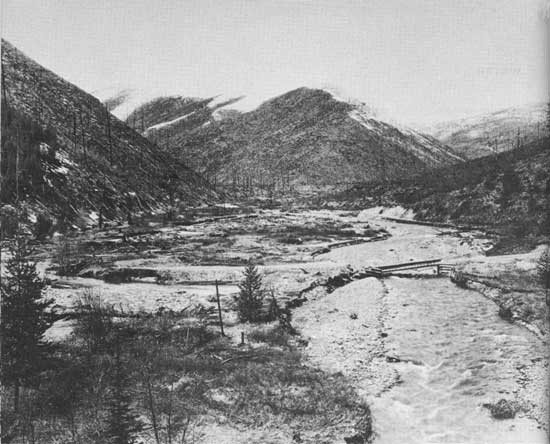

| Fire, then flood. BIG CREEK WATERSHED, CABINET NATIONAL FOREST, IDAHO. F-361709 |

TO GUARD THE CRESTS and all the lands below against excessive run-off, properly managed forest cover offers the best protection known. "It's almost as if God made trees and brush to do this job!" says a forest officer who for years has been studying ways to make a far western forest deliver more gently to parched lowlands the most vital crop of those mountains—water.

The best sort of forest cover presents successive layers of resistance to rapid run-off. First, the treetops: Snow or rain, falling, is detained by the forest canopy, the roof of foliage. Here some of it clings and drips down gradually, but some clings so long that the sun sucks it back into the sky. Water losses upward from snow rapidly melting and evaporating on thick foliage may be considerable. On certain national-forest watersheds where the yield of delivered water is of crucial importance, as in Colorado, the characteristic canopy makes a roof so dense that much snow moisture returns to the clouds without touching the earth. Here systems of cuttings are definitely planned so as, in effect, to make holes in the forest roof and let more water directly down into thirsty soil.

Some water, of course, makes its way quietly down the limbs and the trunks of trees, and enters the ground that way. Other water dripping from the upper foliage is again detained by underbrush, which drips it in turn upon the litter and ground cover, the last conserving layer opposed to rapid run-off of water, and of soil.

In western regions that depend for their very life upon stored water brought down from the mountains, snow reports are almost as carefully followed as are cotton reports in Memphis. "Next summer's rain," the dry-land people say when they lift their eyes and behold clean snow on the mountains. Up the mountains, all winter long, rangers are taking snow samples along trails laid out to touch points of representative precipitation. They travel on skis or snowshoes and take their samples with the thrust of a hollow tube. Machines have lately been acquired, on some forests, to measure and calibrate snowfall more easily, but much of the work still is done without technological improvements.

In any case, the total snowfall recorded does not, like rainfall, signify that that much water will be delivered upon thirsting ground for crops, for industrial use, or for city reservoirs. So much depends on the rate of thaw in the spring. If the melt is gradual, a big snow crop on the mountains is a blessed gift. But if the snow crop piles high and the melt comes abruptly, fiercely, it can play the very devil up there on the mountainsides and below.

"Water-drunk" is another phrase which passes as current, without need of a fuller explanation, among rural and urban dry-land contenders for mountain water brought down to dry lands. Water is the lifeblood of any region, and in semidesert or desert communities men know that. They dream of and fight over water rights with a fervor that more sheltered men in humid climates find hard to understand. The classic fable concerning Tantalus, who thirsted and could see water but couldn't get at it, has a special meaning nowadays to many a western American, concerned as to the continuance of a clean and ample water supply. Lawsuits over water rights in the general vicinity of Hollywood, for instance, greatly exceed in number and importance other court battles of the movie stars, but naturally receive as news much less attention. And it would, when you stop to think about it, be publicity altogether lacking in glamour.

Before closing this chapter on water, let us turn back briefly to the problems sketched in the previous chapter—fire. The relation between destruction of cover and calamitous bursts of run-off becomes each year more shockingly plain. Consider the reservoir now called Harding, in San Diego County, Calif. It was constructed in 1900. It did pretty well until 1926. Then fire got loose and burned off nearly all the cover on its watershed. Torrential rains cut loose on the debris in February of 1927 and this reservoir all but filled with silt and boulders within a month.

On New Year's Day, 1934, newspapers the country over cried of ruin in the pleasant suburban communities of La Crescenta, Verdugo, Montrose, and La Canada, just north of Los Angeles. Torrents of water, mud, and boulders swept down from mountains killing 34 people and demolishing 400 homes. The disaster, wrote Charles J. Kraebel, reviewing causes, clearly indicated a "fatal sequence of mountain-denuding fires followed by rainfall of great intensity."

The slopes above Pickens Canyon, where some of the worst damage occurred, had good shrub and chaparral cover until late in 1933. But late in November, fire destroyed more than 5,000 acres in 3 days. In many places the fire was so hot as not only to wipe out vegetation but also to consume the surface litter. It left only a powdery ash. The ground cooled and lay waiting, utterly defenseless.

Then rains came. On this Verdugo watershed and on nearby similar watersheds, the Arroyo Seco, San Dimas, and Haines, it started to rain heavily, and with a remarkable uniformity of precipitation, early in the morning of December 30. All that day the rain slashed down, all that night, and all of the day and night following. In the last hour of the "old year" gage records show precipitation reached the peak. Nearly an inch of rain fell in that hour. Total rainfall during the 2-day storm ran between 11-1/4 and 12-1/2 inches throughout the foothill country just north of Los Angeles.

On the burned-off watershed, Kraebel estimates, floodwater stripped off and hurled down certainly no less than 50,000 tons of silt, rubble, and boulders from each square mile. The area in question was of about 19 square miles, nearly one-third burned over.

Nearby, an unburned 17-square-mile forest area, the San Dimas, lost and sent down during the same flood only about one-twentieth as much flood water, and only about one-tenth of 1 percent as much erosional debris.

The San Dimas is an experimental forest, equipped to measure run-off under various types of cover and forest management. "Within the forest," Kraebel explains, "are six small watersheds, selected for their likeness in topography and vegetation, and varying in size from 35 to 100 acres. Weirs at the canyon mouths automatically record the stream flow while reservoirs catch the eroded material; recording gages strategically placed measure the rainfall intensity; and, distributed over the watersheds, more than 100 standard gages serve to secure for each storm the most accurate measure of precipitation ever attempted in a mountain area."

Established in 1931, and set up to run as a 50-year experiment, this forest already has evidence to indicate that burned mountainsides can send down 20 times as much floodwater and 1,000 times as much silt and rubble as unburned mountainsides, properly covered. Ordinarily, research foresters do not like to announce tentative findings; they prefer to wait and verify. But the evidence at hand is plain, the situation is crucial, and every year brings further verification.

|

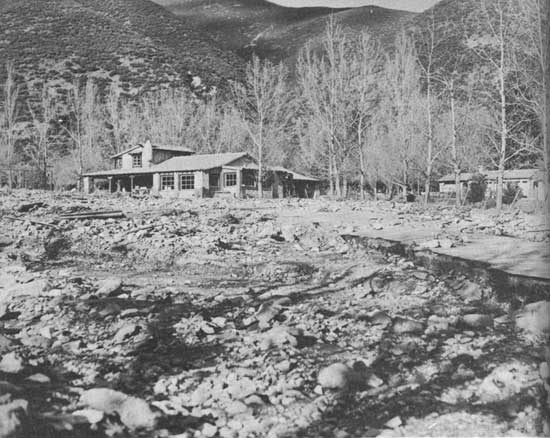

| The water wiped them out. It wiped out roads, camp sites, resorts. LYTLE CREEK, SAN BERNARDINO NATIONAL FOREST, CALIF. F-362018 |

FIRE, THEN FLOOD; it happens again and again, and the demolition of recreational and all other living values is evident. In the same part of California, repeated fires over a number of years had a devastating effect on the soil-binding cover in the Tujunga Canyon. A flood burst down this canyon on March 2, 1938, and wiped out summer homes, built on both private land there and on national forest land under special permit, by the score. This demolition was especially distressing as many of these mountain cabins, put up in flush times as week-end places, were being occupied full time by families down on their luck. The water wiped them out. It wiped out roads, camp sites, resorts. It bit off steel bridges as a man might bite a doughnut. Recreation has been, in large part, forced out of this and other accessible "front canyons" now, because of the debris and because, with cover returning but slowly, there may be a recurrence of smashing floods.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap11.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |