|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part Three

KEEPINGS THINGS NATURAL

Chapter Ten

Fire

More than 72,200 national forest acres were burned over in the calendar year 1937. Some 500 acres burned to every 1,000,000 acres protected. Losses of area have never before been held to so low a total. But the 1937 fire season from the standpoint of loss of life was disastrous. . . .

Fifteen heroic CCC boys met horrible deaths in the Blackwater fire. Thirty-eight others were injured but recovered. The tragedy was due to an unforeseeable combination of sudden changes of weather which deprived crews of what should normally have been a nearby safety zone. . . . The 1937 honor roll of men who died on far-flung national forest fire lines numbers 20. . . .

Report of Ferdinand Silcox, Chief of the Forest Service, 1938.

AN UNEASY FEELING hung over the little group of campers in the big cedar grove on the Priest River of Idaho. It was the first of August. The forest was tinder dry, and there were disquieting rumors of forest fires off to the west.

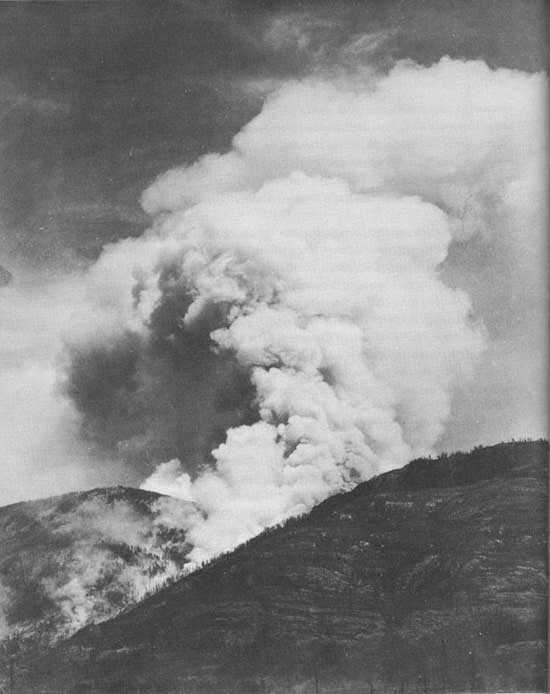

The wind increased and the rumors were confirmed. There came now a steady patter of twigs and pine needles falling on the tents. The campers drew together, excitedly talking. One of them pointed to a white cloud thrust over the timbered ridge to the west. It grew and ballooned into a cauliflowerlike thunderhead. "Fire!" cried a man, pointing. Other cries rose: "The Freeman Lake fire has blown up." . . . "Strike tents!" . . . "Time to get out of here."

Down the road a siren sounded. Three motortrucks loaded with fire fighters thundered by. Smoke settled into the valley, cutting off all distant visibility. Ashes swept up by the great heat draft over the ridge commenced to fall among the cedars. Hastily each family group struck its tents, packed equipment. All ease and peace vanished. The holiday was spoiled. One by one, like startled rabbits, cars scampered out of the forest. By nightfall the fire had swept across the river and the cedar grove camp was in ashes.

|

| All ease and peace vanished. The holiday was spoiled. HALF MOON FIRE, FLATHEAD NATIONAL FOREST, MONT. F-238977 |

The trees themselves, their cool shade, their beauty, and the carpet of woodland plants on the ground, and the bird and animal life all destroyed, and all in a few hours. Nothing remained save smoldering desolation—the skeletons of trees standing dead, a tangle of down logs, and the hot sun beating through to the blackened ground of an open burn. And dust, carbon dust, billions upon billions of minute floating carbon particles; this is all that remained of living trees, of vital forest cover. Products that might have kept unborn generations alive and at ease dust in the air now, to be dead for centuries.

It is hard to put into words the premonitions that dampen the everyday working spirit, or the zest in seizing a carefree day in the open, when a forest fire gets going, creeping or leaping, anywhere within 10 miles or so. A sort of stoic panic grips all the people there, working and playing. It disrupts all planned and purposed work and disrupts outings. The fire may be so far away that no smoke is smelled or seen, but the telephone lines between the fire towers buzz; the forest staff is tense, strained; the air is charged with a sense of insecurity. Small animals and greater forms of forest wildlife begin to cross the trails and roads leeward. Whether they see such signs of the fire or not (generally forest visitors do not), a like impulse unsettles the holiday spirit of forest visitors.

In a bad fire season a pall of smoke settles over the whole country. In such a season the mountains may not be visible for weeks. All distant views are cut off; the major pleasure of being in the mountains is destroyed. The mere report of large fires burning is sufficient to curtail greatly the recreational travel into the threatened country and often wisely so, for large fires bring real danger. Through the course of the years many hundreds of people have suffered terrible death in forests aflame. Campers or travelers do well to keep out of the woods when large forest fires are burning.

The fire season, or the driest time of the year, comes at different months on different forests. In Montana, the greatest danger is in midsummer, when cover is tinderlike and lightning strikes most often. In Florida, the dry time is usually from February to April, before spring rains have greened the scrub oaks and the brush and forest ground cover. Foresters have a saying that you do not have to consult records to gage the fire hazard on a given forest. All you have to do is look at the faces and listen to the talk of the ranger and forest guards. There is truth in this.

The Caribbean National Forest of Puerto Rico has practically no fire hazard. And of such is the reward for being on a tropical rain forest with 200 inches annual rainfall, foresters say there, relaxed and cheerful. Foresters working out from Missoula, Mont., seem by comparison in the summer season, gaunt, tense. There is little laughter among them. "You will not," says Evan W. Kelley, once a major in the A. E. F. and now regional forester in charge of fire control and other Forest Service activities in Montana and northern Idaho, "find West Slope forest officers gay. We are smothered by the work, by the menace, in the fire season. To feel it, come live here in the dry time, with the mountain storms spitting and crackling.

"This season (1938) we had 140 fires going on one 2,000,000-acre area at once. All of them were started by lightning. No special zones of risk; hits all over. The lightning starts duff and snag fires, and occasionally in a dry top of a living tree. Many are hard to find. Not a fire at first, just a creeping smolder. We've hunted for 4 days to find one, sometimes.

"We send out smoke chasers, working in from section lines, with compasses to run down fires reported by the fire towers. We send work crews out, strip the ground a rod or so apart, hunting the terrain for smoldering fires, as if we were looking for a lost child.

"And just when you think you've got them all, and can take a Sunday afternoon off, you get a day of high wind, low humidity, more lightning, and roaring fires to fight all over the mountains. It's a hard game to beat. It takes men with nerves of iron and bodies of steel," says Major Kelley, who adds that when his time comes to retire he is going "to put up a cabin in a swamp, a big one."

In one particular the fire situation on northwestern dry-land forests is less nerve racking than the situation on the forests of Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, and of other far Southern States. There is something impersonal about defending from destruction woodlands fired by lightning. A man can be rather fatalistic about it; he can fight and not be angry. In many parts of the far South, however, and in the most dangerous, the driest season, most of the forest fires are started, more or less deliberately, by human beings. The ignorance, the superstition, the voodoo notions which bring on this deliberate annual destruction of the South's remaining forest resources are hard to fight, or even to contemplate, calmly.

|

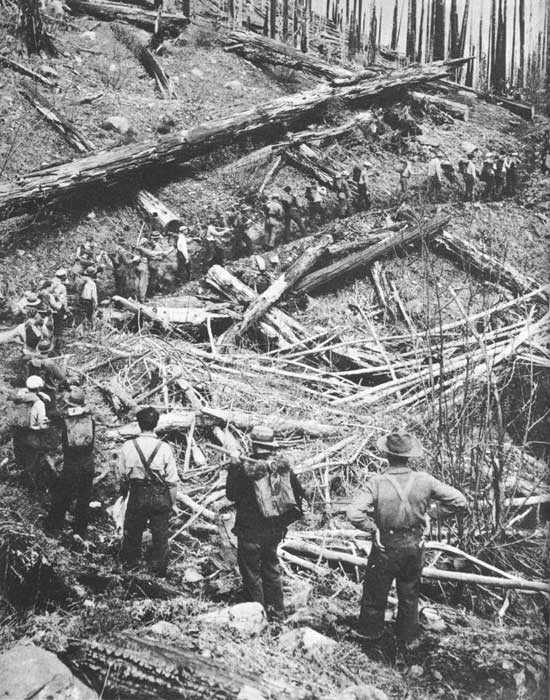

| Nothing remained save smoldering desolation—the skeletons of trees standing dead, a tangle of down logs, and the hot sun beating through to the blackened ground. SIUSLAW NATIONAL FOREST, OREG. F-1055 A |

Anyone who has ever driven in March down through the piney woods, which make a straggling start on the eastern shore of Maryland, rim the coastal plain to Florida, and then turn and march west to Texas, will have seen the thing happening, all along the way. That is when the woods burners, white and black, go out and set fires. It is a regular part of their spring work.

Firing "greens up" the grass, the people there say. They say it kills rattlers, destroys the "germs" of pellagra and of tuberculosis and of infantile paralysis, rids the woods of chiggers and malaria. Probably, it does none of these things but the feeling that it does runs deep. What indiscriminate burning of the forest floor, or open range land, does is to cremate such living organic matter as remains in the upper topsoil. It burns out part of the land's richness. It makes the piece of soil less fertile and all the more likely to wash or blow away. The grass may look green and fresh at first, but its meat-producing values are not improved. It looks like a nice, clean job, maybe, for the first week or so, but the resulting growth is sparser, coarser, ranker.

To burn land off, time after time and right and left, is to hurt and perhaps destroy it. Yet every March as you travel southward in the piney woods, you see people setting grass fires and woods fires on hundreds and thousands of acres. Drive at night, and for miles you will see lands ablaze, untended. Smoke and carbon particles fill the air; the ground flames are as crawling snakes of fire; and here and there you will see them licking their way up tree trunks and flaming explosively in the canopy.

All along the way are educational signs placed there by State and national foresters, patiently reiterating established facts; EVERYONE LOSES WHEN THE WOODS BURN . . . PREVENT FOREST FIRES—IT PAYS. . . .

But still the people go out and set the woods and fields afire.

Partly, it is superstition; and there is a strand of racial memory intertwined which makes the thing hard to get at and change, for thus, by fire, our pioneer forebears cleared their farms from the wilderness, in the main. There is probably an even further throw-back: Man's instinctive hostility to, and dread of, the jungle. There is also the primitive excitement which kindles in all of us the desire to see flame leap and run. Quite a few farmers and woodsmen who ordinarily pass as sane, confess to letting a brush fire get out of hand just to see if they can handle it afterward, just for the excitement, just for "the hell of it."

Others argue that to burn off the brush and weeds is to increase the game crop and the ease of the hunter in getting at it. Burning does make the forest more open for hunters, but as for increasing game, that is doubtful.

Any forest officer who has fought large fires can tell stories of deer, elk, and bear, and smaller wild game burned to death in a sudden sweep of flame, or limping pitifully around the edge of the fire with feet burned and fur scorched. Such great conflagrations as the big Idaho fires of 1910, sweeping 40 miles in a single day, must have wiped out practically all wildlife, large and small, over entire river drainages. After such a fire every pool in the streams is white with the upturned bellies of trout killed by ashes in the water.

"Fire," says Ira N. Gabrielson, Chief of the United States Biological Survey, in a special fire prevention number issued by American Forests, April 1939, "is not a temporary disaster. It burns the crop and it destroys the ability of the land to produce another.

"In 1937 a total of over 20,000,000 acres of wildlife habitat was blasted, scorched, and sterilized by forest fires in the United States. The figure does not include grass fires and marsh burns. If these fires killed only 1 bird or animal to each acre, that would mean a loss of 20,000,000 living creatures burned to death or suffocated in 1 year. But to obtain an estimate of the total loss we must multiply that figure by the number of years that will elapse before the habitat destroyed in 1937 has been restored and is ready once more to produce maximum crops of wildlife. . . .

"In all our plans for the conservative management of our lands for wildlife, we must recognize the fact that whether kindled in ignorance or maliciously or accidentally, forest fires and grass fires are deadly to wildlife."

To BURN COVER IS TO BURN GAME, is a slogan that forest education and information workers have been considering in an appeal to the sporting spirit. It is a true statement, but a little too condensed, too hard to follow, perhaps, for a really good slogan. IT'S BAD LUCK TO SET THE WOODS AFIRE is another slogan recently suggested by John P. Shea, a psychologist, speaking before the Southern Society of Philosophy and Psychology, at Chapel Hill, N. C. This has possibilities.

Dr. Shea has made a special study for the Forest Service of man-made forest fires the country over. He finds an obscure, deep-seated feeling on the part of many that to set the woods afire cleans things up for a new start, puts down diseases and jungle menaces, and in general changes one's luck. "Popular attitudes, habits, folkways, morals, and resentments," wrote a reporter for Science Service, compressing the findings, last April, "are mainly responsible for the burning each year of 'enough timber to build a row of five-room frame houses 100 feet apart from New York to Atlanta.'" The investigators (James W. Curtis of Kentucky, and Harold F. Kaufman of Missouri collaborated) suggest six points of appeal:

1. Legal. Stop burning the forests or you will be prosecuted.

2. Economic. Better forests mean more jobs.

3. Aesthetic. Why destroy beauty?

4. Sentimental. Don't destroy the wildwood habitats of birds and beasts and the outdoor haunts for children.

5. Sports and recreation. Keep fire out of the forests and enjoy better hunting, fishing, and recreation.

6. Bad luck. Finally, inculcate manufactured superstitions to battle against disastrous ones causing fire setting.

"Could taboos be inculcated?" Dr. Shea asked his colleagues at the meeting. "Would ballads and folk songs, if such could be made to order, prove effective in correcting unsocial behavior patterns that are proving suicidal to the people of the South?"

BAD LUCK it is, indeed, when forests, grassland, or muckbeds burn; and the bad luck continues for years on end. A whole complex of natural factors is thrown with each successive burn still further out of joint. When over-drainage in the Florida Everglades dried muck soil to powder, and the powder was fired, and a million acres of it burned for weeks on end in the spring of 1939, The New York Herald-Tribune dispatched to the scene a correspondent, John O'Reilly, who sent back an appalling estimate of disaster, not in terms of persons killed, but in terms of permanent, or an all-but-permanent, derangement of the natural water system, the soil, the wildlife, and the human resources. The United States could stand more of this sort of journalism, and less of the sort which, when great fires blazed on the mountains above Los Angeles last winter, yielded hardly a headline east of the Rockies. But when an unimportant tongue of the flame flicked toward Hollywood, "FILM STARS' HOMES MENACED," the city papers shouted from coast to coast.

Really, a great deal more than film stars' homes was menaced. The entire life and civilization of that western dry land depends on water. Denuded slopes do not yield usable water. Burnt-off, denuded watersheds become more menacing there each year.

Literally, and quite obviously, a curse is laid on soil repeatedly burnt over. Life, along with the soil and cover, becomes each year thinner, less robust, less rewarding, more hazardous.

There is nothing mysterious or other-worldly about the process. It is simply that you blast and disturb a natural continuity of growth and renewal—a marvelously delicate but enduring interplay of living forces which, undisturbed, keep a piece of land intact and rich, and the people it supports, secure.

"In a burned woodland," writes Hugh Bennett, Chief of the United States Soil Conservation Service, contributing to the same symposium, in American Forests, "the very structure of the soil is changed. Following the destruction of organic matter and beneficial bacteria by flames, the soft, crumblike surface that naturally prevails under a leaf mold gradually gives way to a harder, more compact condition. Pelting rains hasten the process along. By dislodging tiny soil particles and taking them into suspension along with charred plant debris, they produce a muddy kind of run-off that tends to seal over the ground surface and make it almost impervious to water. Naturally, this compacting action alone means a tremendous increase in the amount of run-off and the rate of erosion. When it is combined with the demolition of all protecting overgrowth, soil and water losses may be multiplied several thousand times over."

Controlled experiments started at Statesville, N. C., several years ago in a virgin forest area tell a graphic story that "links fire with floods and soil erosion." Dr. Bennett continues: "The ground cover on one woodland plat has been burned each year since 1932, with a blow torch; another and equal plat has been left in its original state. On both plats steel strips countersunk into the earth collect all run-off in measuring vats down the slope. After every heavy rain, the vat of the burned plat is heavy with water, dark with soil. Frequently the other vat is scarcely damp on the bottom. Over a 6-year period the burned plat has shed almost exactly 100 times as much water as the plat in virgin woods; soil losses have been more than 800 times as great."

Loss of timber by fire is appalling. The Tillamook fire of August 1933 killed 10-1/4 billion board feet of timber. Yet the New England hurricane felled a total of only 2-1/2 to 3 billion feet, of which about 1-1/2 billion board feet was salvageable timber. Tillamook's 10-1/4 billion board feet was nearly 3 times the cut of the whole West Coast in that year. The loss was in one of Oregon's finest timber stands. And, said the late F. A. Silcox, "Six years of direct employment for 14,000 men (with dependents, 70,000 people) went up in smoke, with loss of potential lumber values of 275 million dollars. This burnt timber would have built 1 million small homes."

It is known that, besides damaging mature timber, repeated fires kill reproduction, prevent certain age classes from reaching maturity, and result in a forest stand so understocked that it yields far less than it otherwise might. Bad luck, indeed! For more than 30 years the Forest Service has been announcing similar findings and warnings, but more progress has been made, speaking generally, in the technique of fighting forest and brush fires after they have started than in preventing them.

CERTAIN IDIOSYNCRASIES that still distinguish our pioneer American folklore and behavior in respect to fire and weather were strikingly exhibited during the fire season in the far South in the spring of 1939. First, of course, there was the Everglades burn-off, not only of vegetation and game, but of soil ominously burning, a million acres of rich soil burning, and casting a pall of soot over protected country 300 or even 400 miles away. This fire was on private land, for the most part, and there seems little doubt that it was set deliberately, at the outset, by the hand of man.

|

| Society may move to restore what it has destroyed or maimed. TREE PLANTING CREW, COLUMBIA NATIONAL FOREST, WASH. F-349923 |

Three hundred miles away, by air line, floating particles of the burning Everglades made fire-tower observation on the Choctawhatchee National Forest difficult. On some days with a southeast wind, lookout towers were all but useless. CCC boys were then sent out on patrol the woods to look for signs of fire, amid the smoke from the 'glades.

The Choctawhatchee is the national forest mentioned in the opening section of chapter 6 on camps; and the high fire hazard that obtains in that part of western Florida, just before it greens up for summer, was also noted. The ranger and his staff were determined to turn in a good fire record. On quiet days the ranger slipped out and set test fires in safe places, then hooked in a "portable" on the telephone line, to note if the towermen were on their toes. One lookout man who went on serenely describing a long dream he'd had the night before to another guard by telephone, with the smoke coming up within 2 miles of his lookout, was relieved at once and replaced by a man possessed of keener eyes, and not so dreamy. Everyone was alert now, and the fire organization was functioning with smooth efficiency.

Spring came late in 1939 to western Florida, and woods burners were somewhat later than usual in firing the woods. Drought burned hard, but even when fires began to be set outside the protective boundary the ranger, by great vigilance, managed to hold down losses within the forest borders to 3 acres. This was a fire started by a careless smoker, but all it took was 3 acres of some 309,000 acres, the forest area; the smallest loss, by far, ever recorded on the Choctawhatchee, up to mid-March.

Still it stayed dry, and that shroud of Everglade soot continued. Slowly soot rained down on the baked ground, and coated it. Dogs and other animals were dyed black to the hocks from the soot on that brittle cover. Every day the risk and the tension heightened. The ranger, fire dispatcher, and forest guards virtually gave up sleeping; 4 hours was more than they got, most nights. They were gaunt-eyed from strain and worry; and the guards in the towers drawled and swapped yarns no longer, but swore at each other sharply on the 'phone line connecting their towers to the ranger station and dispatcher.

"I got one on 69-1/2. Look at her! She's a snake in the grass!"

The guard in another tower. "Keep your shirt on; that's a chimney glow. Ol' George Pratt's chimney, that's all."

First guard. "I'm gonna report it! Ranger said to report everything!"

Second guard. "Lissen now! Don't give way before the water comes. Let the ranger lay in tonight. He'll need it. [Pause] They tell me a lookout over on the De Soto got so worked up he called the dispatcher every time the moon rose."

First guard. "Ain't it never gonna rain?"

Second guard. "I sure hope that lady brings it!"

Then they laughed. The lady in question provided no end of cackling talk, and a needed comic relief of some sort, during the 1939 spring fire season in Florida, with the Everglades burning. She was a rain maker, a gentle soul beyond her middle years, who employed no apparatus more elaborate than her own person, and a fixed conviction that if she sat by a body of water long enough, even in the driest time, she somehow brought on rain.

She sat there by a lake in the drought, with photographers attending, and the news of her sitting held almost equal interest, to Floridians, with the European situation. Indeed, she made more talk than Europe made there, at the time. But it stayed dry, terribly dry; and every day the woods burners, seeking to hurry the greening, slipped out and set more fires. Most of them were set outside of the forest, to be blown in by a strong northeast wind; but fires were set inside the forest, too. Then came a March day with a high northeast wind, and no soot. Abruptly the fire dispatcher at the Jackson Ranger Station had 15 fires on his switchboard all at once; and in 3 days more than 2,000 acres on the Choctawhatchee Forest burned, about its annual average.

But now, at length, some rain fell, patchily, throughout Florida and to the west; not rain enough to put the 'glades fire out, but enough to dampen things a little, and give the forest guards and fire fighters some measure of relief. A forest inspector driving west from the Choctawhatchee at this juncture, to have a look at the situation on the De Soto, with headquarters at Jackson, Miss., read in the paper at Mobile, Ala., midway, that a Florida city chamber of commerce was giving the lady rain maker a banquet for breaking the dry spell.

Next day on the way to Jackson, up through the De Soto National Forest, rain came so hard and fast that it stopped windshield wipers, halted most traffic for hours, and put out every outdoor fire for hundreds of miles around. Roads were washed out, torrents of debris from denuded hillsides boiled in the bottoms, rivers leaped from their banks; and some 30 miles southwest of Jackson, floodwater performed a feat of erosion so striking as to make news in the press throughout the land.

After dark, the middle span of a highway bridge ripped out. A truck came along doggedly, its headlights dimmed by continuing sheets of rain. Bluntly it plunged into the boiling, muddy river. The truck driver fought his way out of the water somehow back to the highway and tried to flag approaching cars. In all, 14 persons drowned in 6 cars from driving off the broken bridge into the floodwater regardless. Then the truck driver managed to stop one, and the other cars stopped behind it; and the ghoulish work of recovering the bodies began, with newsmen there in their numbers, taking flashlight pictures.

"Yours is a strange and violent country," said a foreign visitor to Jackson, reading the papers. In the street people talked low and mournfully, their heads hanging. And one man, with a cackling humor, half hysterical, told a group at a street corner, as ambulances streaked by with sirens wailing: "That lady in Florida had the stuff, all right. And a lot of people said she was a fake."

Much of this may seem out of order, but nothing in nature is utterly unrelated; and between forest fires, floods, and further catastrophes the relationship is pretty thoroughly established. The measures of loss vary widely, according to climate, and the extent and pitch of the watershed; but the inevitable relationship between the sort of voodooism that impels burning, and the sort of voodooism that leads chambers of commerce to give publicity banquets to rain makers becomes increasingly plain. The result in many places is a wasting and threatened land, neither pleasant nor promising to behold. Let us proceed with this inquiry a little further. The consequences affect forest recreation, most certainly. They bear as well on other questions we must face if we are now to keep this land rich, comely, less worn and ugly; a good and pleasant land on which to make a life, and living, for all.

REVIEWING THE RECORD of 5 years, 1933-37, inclusive, Roy Headley, Chief of Fire Control, United States Forest Service, reflects:

"On the average, 172,000 forest fires a year, and 156,000 of these man-caused! An incredible fact. Everyone studying the subject comes sooner or later to a state of exasperated wonder.

"Not on the national forests where law enforcement has perhaps been more systematic, but for the country as a whole, intentional burners have the discredit of more than 42,000 fires in 1937. Thirteen million of the thirty-six million acres burned annually are chargeable to these intentional fires.1 The trouble is mostly in the South but no section is wholly free from people who fire the woods because they want to.

136 million acres is greater than the land area in Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Vermont.

"Intentional burners are not all alike in motive. A large number have economic reasons for burning. When no feed has been stored to carry cattle through the lean period of the year, they almost starve before the new grass comes in the spring. To burn off the old dead grass enables hungry cattle to get at the new growth a few days sooner. . . .

"Unemployment is responsible for many fires. Despite all precautions to avoid hiring men to fight fire who may have had anything to do with starting fires, some men will try this chance to earn a few dollars when no other job is to be had."

The break-down of forest fire causes for the 5-year period, 1933-37, Headley continues, runs as shown in table 1.

TABLE 1.—Causes of forest fires for the United States as a whole, 1933-37

| Cause | Percent | Number of fires |

| Incendiary | 24.7 | 42,377 |

| Unknown | 7.2 | 12,344 |

| Smokers | 24.4 | 41,857 |

| Campers | 6.3 | 10,778 |

| Debris burning | 13.7 | 23,486 |

| Railroads | 4.3 | 7,408 |

| Miscellaneous | 8.9 | 15,292 |

| Lumbering | 1.8 | 3,049 |

| Lightning | 8.7 | 14,932 |

The preceding fire-cause list shows the situation on all our forest land, public and private, protected and unprotected. On the national forests of the United States, alone, the incendiary loss is much lower, the loss from fires started carelessly by smokers is about the same, and the number of fires set by lightning is, proportionately, much higher. The break-down is shown in table 2.

TABLE 2.—Fire causes on national forest land, 1933-371

| Cause | Percent | Number of fires |

| Incendiary | 11.9 | 1,347 |

| Smokers | 22.5 | 2,533 |

| Debris burning | 10.1 | 1,137 |

| Miscellaneous | 5.1 | 578 |

| Lightning | 38.6 | 4,349 |

| Campers | 8.0 | 898 |

| Railroads | 2.1 | 24 |

| Lumbering | 1.7 | 18 |

"Because of the pyramiding human use of the woods for recreational and industrial purposes," Headley concludes, "the need for a powerful counterattack is necessary on accidental fires as well as on fires resulting from thoughtlessness, carelessness, and incendiarism. That our notorious fire-starting habits can be changed has been demonstrated on some of the older national forests in the East. Deep-rooted beliefs in woods burning and a full measure of thoughtlessness and carelessness in dense populations have been transformed into respect for the forest and effective fire-safety habits. These pioneering transformations have been slow, . . . but they prove that a whole nation of communities can be led to appreciate the forests and to hate fire with an effective hatred."

"WE MUST EDUCATE, we must educate," ran a sentence in the Fifth McGuffey Readers, "or we perish in our own prosperity!" As a simple example of elementary adult education seeking to outpace actual catastrophe, the present American attack on fire, flood, and soil destruction is of more than technical interest. Results thus far vary widely, from section to section. New England has a good fire record, but this was partly the result of a rather low fire hazard in the past. Driving in the White Mountains you will see tourist after tourist flip a burning cigarette butt out of the car window, without thought. You see this very rarely in California; for great fires there, one of which burned a sizable portion of Berkeley, the site of the State University, have served more than words or placards to make the people fire conscious. There are now millions of westerners who would not think of smoking in a car without an ash tray on which to smash out the stubs or the pipe heel; and to throw a match away without first breaking it, they say contemptuously, is a "tenderfoot trick."

There is imminent need suddenly to establish just such habit patterns along the track of the hurricane that swept across New England in September 1938. That blow smashed over some 14,000,000 acres. It left some 2-1/2 billion board feet of timber in that part of the country in an indescribable swirl and tangle of loss and confusion, as wind-thrown timber, drying, rotting, on the ground.

|

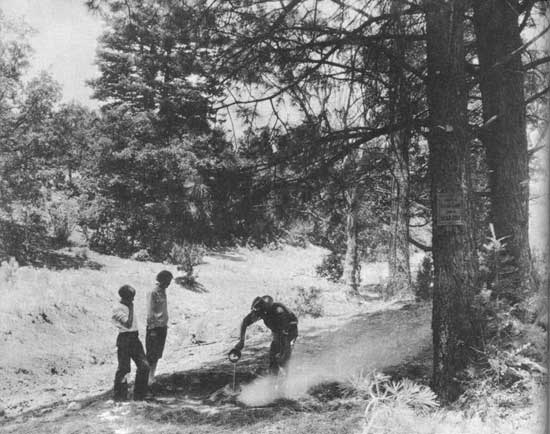

| Visitors are asked to leave a clean camp and a dead fire. TEJANO CANYON CAMPGROUND, CIBOLA NATIONAL FOREST, N. MEX. F-233017 |

"The heavy loss of life and the widespread damage to improved property," writes Dudley Harmon of the New England Council in American Forests forest-fire symposion, "claimed first attention. Then came realization that New England faced a greater danger from forest fire than at any time in its past."

It does, indeed; and the overwinter and spring effort to clear roadside zones, at least, of inflammable slash and debris, wherever the hurricane hit, has been heroic. Thirty-two CCC camps and WPA crews, aggregating 15,000 men, cutting and piling the down timber and whacking out safety strips or fire lines through larger areas of windfall. But the job is too big; it cannot be completed before the fall of 1940, at the earliest, and by then in only a few New England States. In many places New England's fire hazard throughout the dry summer and until snow flies again in the late fall, will be nothing less than terrifying. One live cigarette carelessly flicked away in New England's wounded woods for several summers to come may indeed, as Dudley Harmon says, take hold in tangled, dry debris and kindle "fires of tremendous intensity, so hot in places that fire fighters could not approach them; and if there happened to be several weeks of dry weather followed by high winds, fires might blow from one area of down timber to another, with imminent danger to all in their paths."

Visitors and hunters have been barred entirely from certain forest areas of the highest hazard in parts of New England. This will somewhat impede recreational use on the forests; and many people will grumble, and some will break bounds. In all ways possible, however, the public must be warned and impressed with the danger, for it is literally impossible to change the fire habits of citizens in a humid area within a month or so; and if fires do break bounds in that debris, the result, over such ground as the flames race, could easily be such as would make even the hurricane itself seem a mild visitation, by comparison.

Foresters and woodsmen frequently argue whether opening up trails and roads into the woods, for recreational and commercial use, increases the fire loss, or reduces it. A thoroughgoing analysis of the record, made by Elders Koch and Lyle F. Watts for this report, shows that opening up forests generally increases the number of fires, but also greatly facilitates fighting the fires, putting them out more promptly and effectively, by modern methods.

On 6 western national forests, all existing records since 1924 indicate that campers learned to be about twice as careful with their campfires during the years in question.2 Smokers' fires dropped from 2 to each 10,000 forest visitors to 1 such fire for each 10,000 persons visiting these forests. In view of the fact that far more people, both men and women, have the habit of smoking now than had the habit in 1924-27, the first period covered by this compilation, it appears that the long, slow educational drive against smokers' fires is taking effect. But it is a discouragingly slow business; and so many more people are using the forests now that, while they take about twice as much care with their smokes as they used to, the total number of forest fires carelessly started by smokers has actually increased since 1924.

2A complete tabulation of the data is appended on page 292, Appendix.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap10.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |