|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part Three

KEEPINGS THINGS NATURAL

Chapter Nine

Herds and Humans

Pastoral pursuits have always constituted one of the principal occupations of the human race. Early history would be deprived of some of its most interesting chapters if we were to eliminate from them the many references to flocks and herds and shepherds, and kine or cattle.

In our own West, and especially in its arid, semiarid, and mountainous portions, grazing is still and probably always will be of great importance to people who live there.

Here the shepherd and his sheep, his tepee and his faithful dog, and the contented grazing of well-bred cattle portray important uses of mountain pastures and forest ranges. But they also provide scenes that lend pleasure and romance to mountain travel.

John H. Hatton, in an unpublished manuscript.

GRASS-MADE MEAT and wool are part of a great and needed industry in this country. National-forest land must help to support this industry in the future, as in the past. The Forest Service began allotting national-forest ranges, in place of earlier and unorganized use, some 30 years ago. So grazing antedates recreation as a major national-forest use. It is still a major phase of national-forest use in the West, where large numbers of stockmen depend on national-forest pasturage for summer range.

More than 1-1/2 million cattle and horses and 9 million sheep and goats find forage for a part of each year on the national forests. Twenty-six thousand families are directly or indirectly dependent on these ranges for their livelihood, and on nearby lowland ranges stockmen have invested about $200,000,000 in ranch properties which would be far less valuable without national-forest summer range.

|

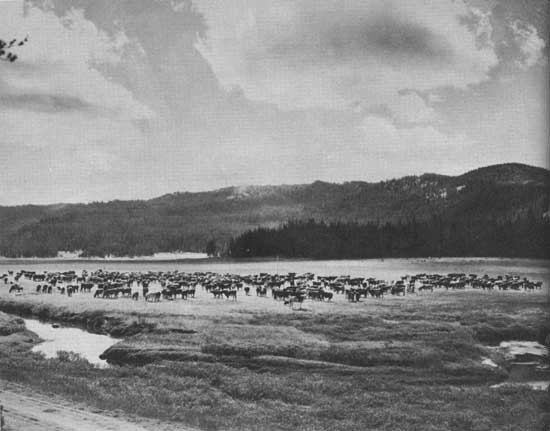

| There are many who like to see flocks and herds on the open range, and count it a part of the pleasure of their outing. BEAR VALLEY, PAYETTE NATIONAL FOREST, IDAHO. F-308625 |

Southern and eastern national forests do not occupy an important place in the livestock industry; they are not adapted by nature to the use of domestic stock on an open-range basis as in the West. Comparatively few livestock are permitted on them. So herds and humans rarely get in each other's way back East, and the same thing holds true over the greater part of the national-forest area, for less than half the total area is now grazed by domestic stock.

Moreover, the Forest Service closes entirely to grazing certain virgin, natural, and other special types of areas having definite recreational appeal; and of the 14 million acres of wilderness areas, 6 million are not grazed by domestic livestock or are used so slightly that essentially primitive conditions of vegetation can easily be maintained.

There are many who like to see flocks and herds on the open range and count it a part of the pleasure of their outing. To them the sight of a band of sheep scattered over a distant hillside, or of a lone camp wagon silhouetted against the evening sky is pleasing. It seems a part of the romance of the West. The dude ranches, many of which are located in or near the western national forests, came into existence largely because of this desire of the vacationist to share in what is left of the picturesque life of the range.

But livestock and forest guests frequently get in each other's way in the more accessible areas along roads and highways. People seek these spots for recreation and, as might be expected, find that many of these easily reached lands have long been grazed. Yet it is often possible to avoid discord by planning more carefully the developments for recreational use.

For example, if the grazing use of a very large area should be wholly dependent on a relatively small water source, the location of a campground or group of summer homes around this spring or lake would necessitate the abandonment of grazing over the entire area. With a little advance planning, however, the recreational concentration undoubtedly could be placed elsewhere and the smaller amount of water needed for recreational use obtained by wells or improvement of springs. Similarly, on many roadside or near-roadside areas the recreational use often justifies the fencing of the campground against livestock. The fences are usually hidden so campers have no feeling of being "shut-in." The cattle-guard entrance is made to merge attractively into the surrounding scene. Plans must also be made to avoid concentration of hunters around the more important stock watering places. "Accessibility" is not a static condition, and sudden changes in accessibility of national-forest areas through road construction bring with them an obligation to foresee possible conflicts in land use and to do the advance planning necessary.

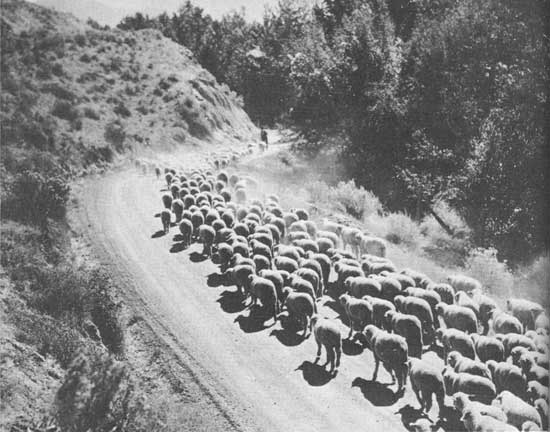

Stock driveways needed to get stock to back country, often through areas closed to grazing, are sore spots in coordination of forest recreation and grazing that are not always easily healed. Often these driveways have been in use several decades. They naturally follow the easiest routes of travel. The roads built later have in many instances paralleled them. And now that the campers and tourists are following the roads, the stock driveways, because of the dust and trampled vegetation for which livestock are responsible, are destructive to the recreational value of such areas. Whenever recreation is a sufficiently important land use, one solution to this particular problem is to change the location of the driveways if at all possible. Where relocating the driveway is not feasible, recreation must adapt itself to the situation or be diverted to other areas. In recent years the use of motor trucks to move livestock to and from the national-forest ranges has lessened the driveway problem to some extent, but driveways will probably always be needed for the movement of livestock to and from roadless areas.

When changes in location of driveways are made, the new routes avoid stream courses and the regularly used recreational roads and trails. So far as possible, these new driveways are along ridge tops, where damage to vegetation is less severe than in the valleys. More than 750 miles of new stock driveways were constructed by the Forest Service in the 5-year period 1933-37. The stockmen have been able to use these less convenient driveways, but such changes are often difficult and frequently very expensive. Further progress in solving this problem will require patience and understanding on the part of both the stockmen and the people on pleasure bent.

GRAZING AND RECREATION . . . A problem that has appeared in some places is to provide ample forage for saddle horses and pack stock used on horseback trips through the mountains. As such trips become more popular, it will be necessary in certain localities to plan grazing so as to leave more feed than has so far been left for visitors' pack and saddle stock. This may involve changes in grazing allotments, or it may be necessary to defer regular grazing until after the recreational season.

|

| And now that campers and tourists are following the roads, stock driveways are destructive to the recreational value of such areas. LOLO NATIONAL FOREST, MONT. F-350932 |

In contrast to these relatively small areas, there are a few rather large areas suitable for grazing on which recreational use is so great and so obviously the pre-eminent land use that grazing of domestic livestock must be entirely excluded. On the Pike National Forest in Colorado, for instance, the forests near Colorado Springs are frequented by so many vacationists that the people alone tend to wear out the grass by "milling around" over the lower slopes of Pikes Peak. And on Los Padres National Forest near Los Angeles, so much land is needed for concentrated forest recreational use that, over large areas, livestock is not grazed.

There are other large areas of "back country" from which small groups of enthusiastic recreationists sometimes insist that absolutely all grazing of domestic livestock be excluded, although the number of forest visitors affected is small. The objections of these small groups are centered not so much in the physical damage that might be done by livestock, but more in a strong and very sincere feeling that the primitive qualities of the national forests are destroyed by the mere presence of sheep and cattle even though the animals may be miles away and unseen. It would seem, however, that with the complete absence of livestock from nearly 100,000 acres of concentrated recreational use, from 6,000,000 out of 14,000,000 acres of wilderness, and from more than 85,000,000 additional acres, it is not necessary to jeopardize an important industry by entirely excluding grazing from the less than half of the national forest area which remains.

In the past undesirably heavy concentrations of livestock near routes of recreational travel have resulted from salting cattle near roads and trails. This was unobjectionable in the days before the people began to use the national forests in large numbers. For the most part it has now been eliminated by establishing salting grounds elsewhere.

The bedding of sheep night after night in one place leaves unsightly scars on the landscape, and depletes the nearby range. And the bedding of sheep near campgrounds interferes with the fullest enjoyment of camper guests. These difficulties were anticipated years ago, and on the national forests administrative efforts have for years been directed toward eliminating them. Approved range-management practices prevent the bedding of sheep near campgrounds and picnic areas, and Forest Service bedding rules are intended to preserve vegetation by prohibiting the use of the same bed ground for more than 3 nights. Bedding out—bedding wherever night overtakes the herd—is a common practice which results in only a 1-night use of each bed ground.

Overuse of range by livestock not only interferes with full enjoyment by forest visitors and detracts from the natural attractiveness of forest landscape, but also damages the soil and forage. The practice of the Forest Service, therefore, is to make such adjustments as are necessary to bring use of ranges into balance with forage production. Since World War times, when many forest ranges were stocked beyond capacity in the interests of maximum meat production, reductions in numbers of stock on national-forest ranges total 839,000 cattle and 2,854,000 sheep, or 37-1/2 percent of the cattle and 33-1/2 percent of the sheep previously allowed on national-forest ranges. Since some of these ranges are still overstocked, further reductions are necessary.

TAMED vs. WILDLIFE . . . The Forest Service policy is to so restrict grazing by domestic livestock that enough forage will be left for reasonable numbers of wildlife, and especially for such big-game animals as deer and elk. But certain practical difficulties stand in the way. Winter range is a controlling factor in big-game populations. Many national forests contain no areas suitable for winter range, or very few. Many winter ranges of former years have been absorbed in agricultural developments. Big-game animals which use summer range in the higher portions of the Cascades, the Sierras, and the Rocky Mountains, for example, are forced by deep snow to seek low-lying winter ranges outside the national forests. The forage on these lower ranges is often privately owned and fully utilized by livestock.

Other difficulties include State game laws which do not permit removal of game in excess of the feed supply; public sentiment unfavorable to the extension of hunting seasons to serve that purpose; or failure of hunters to do so in open seasons. Any one of these may allow big-game herds to increase beyond the capacity of available ranges, and to starve to death in alarming numbers. The deer herd of the Kaibab Plateau in Arizona, the Northern Yellowstone elk herd, and the South Fork herd in the Flathead National Forest in Montana are notable examples of uncontrolled increase in herds which, even after exclusion of livestock from large areas, resulted in destruction of the forage resource and decimation of the animals by starvation.

The other side of the picture is more encouraging. Because the feeding habits of the different animals are often such that vegetation left untouched by one is eaten by another, there is almost always room for a rather large population of big-game animals on most properly stocked livestock ranges. Moreover, more than half of the national-forest area is not used by domestic stock, and these lands provide much feed for wildlife. Included within this total are some 3,000,000 acres of national-forest lands which might be used by domestic stock but which have been closed to such use. These special areas include the more important of the few winter ranges on western national forests, and some summer ranges that are especially needed by wildlife.

On the whole, competition between domestic stock and big game for forage on the national forests is not great. Where such competition does occur there is only one sensible solution, and that lies in joint action by the responsible agencies. The Forest Service is responsible for administration and protection of the land and its resources, while the State game commissions are actively engaged in the administration of the State game laws. These agencies, acting jointly, and in cooperation with stockmen and sportsmen, should be able to work out sensible adjustments.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap9.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |