|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part Three

KEEPINGS THINGS NATURAL

The day is almost upon us when canoe travel will consist in paddling up the noisy wake of a motor launch and portaging through the back yard of a summer cottage. When that day comes canoe travel will be dead, and dead too will be a part of our Americanism. . . . The day is almost upon us when a pack train must wind its way up a gravelled highway and turn out its bell mare in the pasture of a summer hotel. When that day comes, the pack train will be dead, the diamond hitch will be merely a rope and Kit Carson and Jim Bridger will be names in a history lesson.

Aldo Leopold, in American Forests and Forest Life. October 1925.

Chapter Eight

Timber and Recreation

The tree speaks: "Ye who pass and would raise your hand against me, hearken ere you harm me! I am the heat of your hearth on cold winter nights; the friendly shade screening you from the summer sun; my fruits are refreshing draughts, quenching your thirst as you journey on.

"I am the beam that holds your house, the board of your table, the bed on which you lie, and the timber that builds your boat. I am the handle of your hoe, the door of your homestead, the wood of your cradle, and the shell of your coffin. I am the bread of kindness, and the flower of beauty."

From a sign in the park of a European city.

|

| There is no compelling ultimate reason why this industry has to gut its sources, leave them dead. LAND CUT-OVER UNDER PRIVATE OWNERSHIP, ST. JOE NATIONAL FOREST, IDAHO. F-365172 |

OUR COUNTRY NEEDS TIMBER, even in this age of steel. We need timber not only for the most obvious uses for houses, barns, railroad ties, furniture, boxes, fence posts, firewood; but also for a developing variety of chemical woods products, thoroughly modern. For plastics, films, lacquers, cellophane, newspapers, wrapping paper; for the finest grades of writing paper, and ammunition; for naval stores, distillates, dyestuffs, rayons, and for thousands of other products that modern chemistry is developing from tree cellulose as a base, we are going to need and to use forests more and more.

When Jamestown was founded, we had about 820 million acres of forests in the continental United States. We have about 630 million acres classified as forest land today; of the 176 million acres in national forests, 134 million acres are forest land. Vast as they are, our national forests comprise less than one-fourth of the remaining forest land.

The total area classified as forest land, private and public, is bigger than all our country east of the Mississippi River. But the Forest Service figures that nearly 1 acre in 4—168 million out of 630 million acres—is useless as commercial timberland. Thrown together, this 168 million acres would more than blanket all of Maine plus all of New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, West Virginia, and Ohio.

Yet often this noncommercial forest land, of which more than 4 acres out of every 10 is in public ownership, if sensibly handled can serve most usefully in protected watersheds to reduce damage by floods and erosion, to clear up muddy streams, to restore depleted and impaired water resources, to conserve and multiply remaining wildlife, and to afford recreation.

Hunters go wherever the game can be legally shot. They tramp across cut-over lands as freely as through unlogged forests, across reforested fields as readily as over native mountain meadows. Fishermen try their luck in almost every sizeable stream which has any fish and in all but a few of the most remote lakes. They, too, generally concentrate especially near roads and population centers, so that the streams in these vicinities are often completely fished out. Nevertheless, a-fishing they go wherever there is water enough to wet their lines.

And so it is, in a measure, with motorists, picnickers, and campers. The country 'round about may be skinned bare and unattractive. The forest scene may present no sylvan aspect whatsoever only denuded mountainsides and fish-depleted streams left after a recent heavy burn, or dense dry brush fields, or the clear-cut pulpwood operations of New England, or the dredged-up wastes in the lower reaches of streams on the Tahoe and Eldorado National Forests in California. But fishermen come to enjoy the poor fishing on streams in some of the ugly burns. Energetic walkers sometimes include the brush fields in cross-country hikes. Hunters look for deer in the cut-over New England pulp lands, and curious tourists drive the rough roads by the Tahoe tailings to see how gold is gathered from the leavings. Such use is welcomed for whatever pleasure it can bring, but it will not materially affect the land planning of stricken areas now included in the national forests.

Where there is no timber, recreational use and forest industries naturally do not conflict. But many restless people throng where timber is best. There are often roads there, to get the timber out; and these roads get broader and harder each year, speaking generally, as more and more timber is moved by truck.

Lumbering operations and recreational use conflict measurably in many places, and they conflict most seriously in places where it is impossible for the local people to live without logging and the attendant industries.

Sawmills, planing mills, remanufacturing plants, furniture and other factories, together with the forests supplying them, had, in "normal" times, a capital value estimated at 10 billion dollars. The woods industry is pretty well on its back now, especially at the source of supply. But in 1929 it contributed about 3 billion of the 80-billion-dollar national income, and in normal times it supports some 6 million people, their homes, churches, and schools.

There is no compelling ultimate reason why this industry has to gut its sources, leave them dead. If rather simple sustained-yield measures, plainly demonstrated on private lands here and there and on the national forests, were to spread in practice much faster than they are now spreading, there is no reason why our remaining forests may not provide refillable reservoirs of materials, employment, and sustenance for more than twice as many people as they do now.

Such possibilities, and the risk of another final surge of despoliation, apply especially to the South, where technological imponderables enter fast into a changing picture. The South, as has been noted, boomed and spread in the main on cotton. Then healing pine marched into vast washed-out cotton lands. It used to be thought that the pitch in these southern pines made them useless for the better grades of paper pulp and for rayon. Thanks to pioneer researches of the Forest Products Laboratory and to those of a great Georgian, the late Charles H. Herty, this now appears untrue.

In consequence, new mills and big money are rushing into the South; and pulpwood towns northward, in Canada and from Maine to the West Coast, are beginning to feel economic pressure from the South's rapidly expanding pulp and paper industry.

The southern agrarian poets and writers who worry about the South's commercial eagerness to forget wage standards, which forces chambers of commerce to forget taxes; to forget almost anything except a dire need to attract tourists, industries, and pay rolls; and to go industrial full-tilt—these southern agrarians really have something to worry about in the recent expansion of the South's paper industry. So have State and Federal forest administrators, from ranger to Chief of the United States Forest Service, from fire warden to State forester.

|

| The forest must be cropped rather than mind. SOUTHERN KRAFT CORPORATION LANDS, CALHOUN COUNTY, ARK. F-363611 |

In all the Southern States together, 18 new pulp and paper mills were established or projected between January 1, 1936, and June 1, 1939. These made a total of 51. These mills alone may require 4 to 5 million cords of rough wood annually. But even though annual forest growth in the South of all species and all sizes exceeds total annual drain by 7 million cords, the picture is none too rosy. Old-growth and saw-timber stands are in general understocked. But from analyses made in many forest-survey units of some 6 to 10 million acres each, it is known that forest growing stock in the South generally can be built up; that annual increment can be doubled, at least.

Nature, prodigal as she is, must be aided by man before southern forests as a whole can double their present growth. Fortunately, most of the things man must do are obvious and rather simple. Adequate fire protection must be provided. The forest must be cropped rather than mined. Growing stock must be built up. And these things must be done on all forest lands, no matter who owns them.

Among the new concerns that have come in so rapidly to take southern pulpwood some are following admirable forestry methods, but many others are not. Certain of the larger companies have made hopeful starts toward sustained-forest use, but others exhibit again, in varying measure, the same reckless methods by which so many million acres of forest land have been laid waste. Unless such companies or corporations, including sawmills and other forest industries, can be brought to see the waste and suffering they are creating, and quickly, it may be for great stretches of the Southland the same old story repeated; and this time it may be an even sadder story.

If, on the other hand, these industries are developed on the basis of sound forest practices, they may prove a continuing support for a much higher standard of living than now prevails.

NORTH AND SOUTH, EAST AND WEST, national forests must demonstrate the best ways to recreate a sustained source of income for all those millions of our people who live by commercial woods products. Human recreation has to be meshed or fitted in with this and with other forest uses.

With about one-sixth of the commercially useful acreage, the national forests contain one-third of the Nation's saw timber. The very existence of many established communities depends now on the assurance of continuing supplies of this Government timber, which can often be combined with private timberlands for joint sustained-yield management, to provide continuing supplies for permanent wood-using industries.

In many such places the claim of the hunter or vacationist, and the claim of the woods industries upon the national forests clash. Can both interests be served? In large part, yes; but it takes intelligent planning, sound coordination, and some yielding on both—and all—sides.

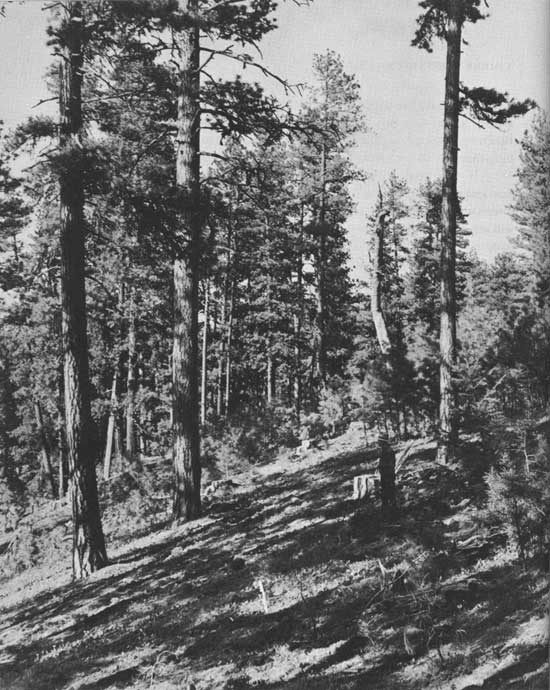

Few will claim that timber operations, however judiciously conducted, enhance woodland charm. The most complete sanctuary inheres in the natural state. From the far corners of the world people come to see and absorb the unimaginable majesty of the Pacific groves. A man would be indeed lacking in sensibility who could stand in the midst of the giant tulip poplars and white oaks of a virgin Appalachian cove or the towering, many-centuries-old trees of a primeval Douglas fir forest in Oregon and not feel it sacrilege to lay ax to a single one of them.

Yet timber is needed; harvest must come, and must inevitably destroy some of the beauty and interest of the forest. But though the larger and older trees are taken, all is not lost, by any means. The young forests that succeed their harvested forebears may also be beautiful. The vigor, the push of the trees toward the sky, and the promise of things to come may capture the imagination and enchant the eye.

The actual result is a compromise, some sort of a reconciliation, with civilization. It may be made a happy compromise. And the commercial and aesthetic aspects may be in some part segregated, each from each.

PRIORITIES . . . Foresters establish for any given area a planned priority of use. Here, they say, lumbering shall be the dominant activity; here lumbering and grazing shall be codominant; and here is where the pleasure seekers may have first claim. It is all tentative; they know that, but it is earth-born of need.

The typical national forest is not a solidly timbered area. Topographic and soil variations break it into a complex pattern of valley, plateau, mountaintop, canyon, stream, and lake. The vegetative cover may be heavy timber, second growth, subalpine or scrub forest, grass, or brush. Within this pattern, the commercial timber productive area may make up approximately 50 percent of the whole. This is distributed variously, sometimes in large solid blocks, but often in belts and stringers up the stream valleys.

The various classes of land are in general so intermingled, as nature has laid them down, that management must treat them as one harmonious whole, giving each portion the use or uses which it best serves, whether it be timber production, grazing, or recreation, or, as is usually the case, a combination of several uses. No one use can be planned without consideration of the others.

Commercial timber does not on the average occupy more than half of the national-forest area. The possible conflict between timber cutting and recreation is at once limited to this extent. Actually the possibility of important conflict is much more sharply limited because the heavily concentrated forms of recreational use of the national forests involve a relatively small portion of the whole forest area. People drive the roads, fish the streams, and camp or picnic by the streamside or lakeside. Beyond this concentration, which is chiefly in the stream valleys, is the more general distribution of a smaller population of hunters, hikers, horseback riders, and berry pickers.

The important thing at present is to set up the necessary zones for special treatment. It is easy to cut a 500-year-old tree, but it takes a long time to restore it. The approximate average life of a coast Douglas fir is 600 years, a western white pine 350 years, a western larch 500 years, a white oak 350 years, a lodgepole pine 200 years, a ponderosa pine 500 years, a tulip poplar 250 years. The time involved in the life of such trees is so long that it is vital for ample areas of them to be preserved.

Much of the feeling which has developed among nature lovers against timber cutting has been heightened by the pioneer form of timber liquidation on private lands. That, of course, usually is not forestry, practiced as long-time husbandry, at all.

|

| But though the larger and older trees are taken, all is not lost, by any means. SELECTIVE CUTTING IN PONDEROSA PINE STAND, MALHEUR NATIONAL FOREST, OREG. F-348246 |

SUSTAINED YIELD . . . For each type of commercial timber in the national forests, the Forest Service aims to develop techniques of management which will serve to renew and reproduce the cut-over stand, and keep it continuously productive. This affords maximum opportunity for employment, and helps contribute to continuity and stability of dependent communities. These methods vary, and all problems have not yet been solved. But recreational values are naturally best preserved by the methods which least disturb the forest cover.

The ponderosa pine type is the most widespread of the important western timber types. It is normally an uneven-aged forest, and adapts itself to a system of partial cutting at intervals of 20 to 50 years, each operation taking out the oldest trees. With the development of truck transportation, the tendency has been for cutting to become even lighter than in the past, the first cutting sometimes removing not more than 30 to 40 percent of the volume, causing very little break in the forest cover and little reduction in the general recreational value of the forest. This system of cutting is now in effect over large areas in the national forests.

The west coast Douglas fir type offers a more difficult problem in maintaining scenic values. The old-growth timber occurs in very heavy stands and the trees are so large and so old that in the past the usual practice has been clear cutting, with reseeding accomplished through scattered seed trees or uncut blocks or strips. Within the last decade, however, powerful trucks and tractors have made selective logging physically possible. A few years ago information accumulated by research and administration indicated that, from the standpoint of economics as well as that of silviculture, it was possible to apply within some of the Douglas fir type a selective system modified to fit that type. This modified system is now adopted, as far as conditions and circumstances make it possible, in Douglas fir stands on the national forests. It is also being tried out on certain private holdings. Modification in past practice also included more effective screening of cut-over areas by roadside zones and other well-located uncut areas, and where clear cutting is necessary, a wider distribution of cutting areas.

The lodgepole pine, a predominant type in the Northern and Central Rocky Mountains, has been managed chiefly by some form of partial cutting. Vast lodgepole areas cut over for railroad ties and mine timbers in the last 30 years bear evidence that areas logged by forestry methods may still be green and attractive. Such areas are today commonly used for recreation.

The various hardwood types that occur in the eastern and southern national forests are generally well adapted to selective cutting, although, as in all types, there are portions of the stand in which clear cutting may be the best form of silviculture. Very heavy recreational use takes place on many hardwood stands that have been selectively logged.

|

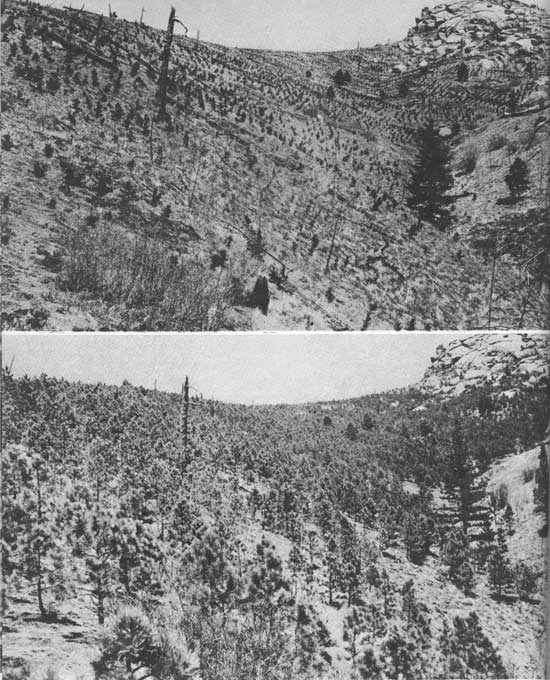

| Artificial planting is a form of timber management distinctly beneficial to recreational use. PIKE NATIONAL FOREST, COLO. F-15336, F-345360 |

On the other hand, the red spruce and balsam fir forests growing on the upper slopes of the eastern mountains usually require some form of clear cutting because any reserved trees of these shallow-rooted species are peculiarly subject to wind-throw. Clear-cut areas in this type are followed by excellent reproduction, provided fires are kept out, but scenically they are unattractive until the new stand is well along. Consequently, in the spruce slope type either recreation values must be sacrificed for considerable periods or commodity values given up altogether.

Methods of disposing of logging slash have an important bearing on forest appearance after logging operations. The continuing tendency to reduce the intensity of cutting on national forests results in a decrease in the amount of slash.

Artificial planting is a form of timber management distinctly beneficial to recreational use. Hundreds of thousands of acres of unsightly old burns have been restored to a green forest cover through national-forest-planting activities. In 1938 alone, 154,000 acres, an area four times the size of the District of Columbia, were planted on the national forests.

In various parts of the United States one finds convincing proof that timber cutting and recreation may go hand in hand. Most of the heavily used recreational areas of the Lake States have been cut over, but people there have made some headway toward restoration in the past few years.

New England is a region of heavy recreational use. Much of this use is in areas where the original forest long ago gave way to second- or third- or fourth-growth stands. There are countless little wood-using plants getting raw material from the same forests that millions of people frequent for pleasure. And the reconciliation of the demands of millions of forest visitors with the harvesting of successive timber crops in northern New Hampshire is, perhaps, the best example of the multiple-use form of national forest management. The cut of timber from the White Mountain National Forest this year will represent about $52,000, of which 25 percent or $13,000 will be returned, in lieu of taxes, to the counties in which national forest land is located. The forest has paid more than $192,000 to the States of New Hampshire and Maine.

Simultaneously, the recreation business has grown to be one of New Hampshire's most profitable sources of revenue. As early as 1935 returns reached the impressive total of $75,000,000, of which $18,000,000 is estimated to have come from the White Mountain area.

Thus, public management may reconcile divergent interests and uses and deliver, from forest and wild lands generally, "the greatest good to the greatest number of people in the long run."

The ponderosa pine stands in the Black Hills of South Dakota have been cut by forestry methods for more than 30 years, yet thousands of people visit this area each summer and delight in the beauty of the growing forest. The overmature trees are gone, but the many near-mature trees and saplings which have remained after selective logging furnish refreshing shade and beauty to people from the Great Plains who visit these cut-over forests for their vacations, and dash out amid lightning bursts, in thundergusts, to let the spilled, whipped rain beat upon them, a release from drought and deprivation, a renewal—hope.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap8.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |