|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part Two

KINDS OF OUTINGS

Chapter Seven

Winter Sports

But, jovial and ruddy as winter sports are, they have a side which is more or less lacking in the sports of summer . . . They have a lonely side, a still reflective side, which, for some of us, adds immeasurably to their charm.

Walter Prichard Eaton, Winter Sports Verse, 1919.

A WORLD-WIDE DRIVE to get out and play in the snow first became evident, social historians may note, in troubled Europe following the shock and dissolutions of the World War, 1914-1918.

Children, of course, have always made snow men and coasted, and so have a few of their elders. But adult winter sports in the past had principally to do with going places sleighing, snowshoeing, climbing mountains, mushing along behind a dog team. The pleasure derived was incidental, a byproduct of the journey, for grown-up people, as a rule.

It becomes almost tiresome now, by spring, the square mileage of winter-sports pictures that city-pent people see in the papers, and the acreage of bare skin, of both sexes, displayed in the news pictures, still and moving, all winter long. Actually not much skiing is done naked, or nearly naked, except by ardent health fans or for publicity "shots." But the lighter, less burdensome garments worn now by winter sportsmen and sportswomen, and the way in which they get wind and sun burned in winter, do suggest an important and healthy advance in civilized living habits.

|

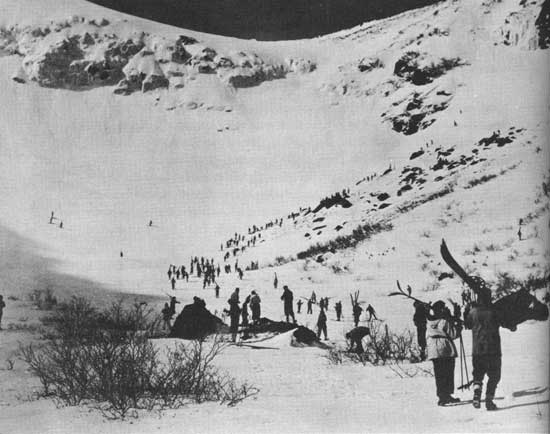

| It is as if you were in another world—sharp, clean exciting, robust. ALTA BASIN, WASATCH NATIONAL FOREST, UTAH F-360887 |

All this has played a part in the amazing burst of publicity that has pushed winter sports along so fast, both here and abroad. In some countries the publicity has been dictatorial in origin, put out by the Strong Man to advance the general health, ruggedness, and spirit. Here with us growth in popularity of winter sports has resulted from years of effort by officers and members of skiing and other outdoor sportsmen's organizations. More recently commercial interests have joined in the push. But everywhere the thing has proceeded in the thought that here is something that millions need and want, and the results have been to the good, in the main.

Much that is filmed and printed of winter sports in this country plays up naturally from the sports-page angle, professional performances. From the resort standpoint, there is a tendency also to surround skiing, as golf, polo, and horseback riding have been surrounded, with an exclusive aura, to smother its development in snob appeal. This is short-sighted and ridiculous. There is nothing essentially expensive about winter sports—nothing exclusive.

It is good, this general spurt of escape from the stuffy and weary prison of overheated houses and head colds by Americans still young, and not so young. It marks, in a way, a break with the past, this discovery that the sun shines also in winter and that the most exhilarating of experiences may be enjoyed in brisk weather, outdoors. For thousands, this discovery has meant a break in that dulling annual hibernation which even open-country Americans have tended to indulge in from the first. The speed with which general participation in winter sports is increasing may be judged from a pleased announcement by sports tradesmen early in 1939.

In 1935 Americans spent for skis and snowshoes $417,000. Last year, 1938, they spent $3,000,000 for skis, $6,000,000 for ski clothes, and $15,000,000 for transportation to and lodging at winter playgrounds, private and public.

From the Appalachians near the Atlantic, across the Lake States, through the Rockies, and westward to the Cascade Range and the Sierras above the Pacific, each winter week end now brings a colorful throng of enthusiasts to white playgrounds. Probably no other form of outdoor recreation offers a wider range of appeal. The small boy with home-made sled or barrel-stave skis has as much fun as the expert with his carefully chosen equipment. Not everyone can learn to ski jump, or should try to, but nearly all can find exhilarating play in simpler ways. There is coasting. Not only the very young can coast, anyone can; on anything from the short easy slope where the youngsters slide "belly-buster" to the long steep toboggan run. There is snowshoeing. On snowshoes one can get off the beaten track and enjoy the white solitude and the ever-changing sparkle of winter forest landscape. The photographer and the wildlife observer may enter new worlds of beauty walking on "webs." Skating, mountain climbing, cross-country trips on skis or snowshoes, sleighing, skijoring, rides behind a dog team— all have a place in winter sports. And the stout, plain, colorful clothes that have come into use by both men and women for winter sports add vastly to the vivacity and pleasure of the experience. It is as if you were in another world sharp, clean, exciting, robust.

Winter sports have an origin in necessity. Man made the first snowshoes, skis, and sleds to aid him in needful travel across snow-covered country for winter food. The use of skis antedates written history. The most primitive snowshoe was probably woven of reeds. It is thought to have originated in the Altai Mountains of Central Asia. In the United States the first over-the-snow travel was on rackets or webs fabricated by the Indians.

Scandinavian settlers in Minnesota seem to have used skis as early as 1840. One of the first written descriptions of the use of skis in America, however, is that of Rev. John L. Dyer, who mentions the use of Norwegian "snowshoes" from 9 to 11 feet long. He used them to carry the mail in Colorado in 1861 and 1862. A little earlier, about 1856, John A. (Snowshoe) Thompson also carried the mail by ski from Placerville to Carson Valley in the Sierras.

FOR SHEER SPORT . . . The first American skiers for pleasure only, it seems, were Norwegians, Finns, and Swedes, who migrated to New England and the Great Lakes country as woodsmen and found the snow and terrain suitable for their native sport. This led to organization of the first ski clubs in the 1880's in New Hampshire and Minnesota. Sondre Nordheim and Turjus Hemmesveit introduced ski jumping. In about 1890 a ski jump was built at Frederic, Wis. In 1887 the Ishpeming Ski Club of Michigan organized the first formal jumping tournament in the United States. The National Ski Association was organized in 1904 at Ishpeming, Mich. In the Northeast the sport was promoted by colleges and outdoor organizations, notably the Dartmouth Outing Club, as well as through the efforts of resorts featuring winter sports as a part of an all-year recreation program.

As early as 1886 the Appalachian Mountain Club of Boston organized snowshoe excursions into the White Mountains. This club encouraged snowshoeing "not only as an exercise, but more especially as a help in mountaineering." Later the Sierra Club in California, the Mazamas in Oregon, the Mountaineers in Washington, and the Wasatch Mountain Club in Utah, did the same.

The early Scandinavian-Americans skied as they had at home, standing straight. They darted down the virgin slopes of this continent erectly with wings that they carved from the woods on their feet. They started our present boom of pleasure skiing.

It was an Austrian-American, a later pioneer, still hale and active, who made the discovery which more than any other so multiplies ski trains, ski schools, ski trails, and ski sales in this land today. His name is Hannes Schneider. He got the idea that man can fly better, faster, farther over the snow if he crouches. He made of skiing a beautiful and exciting art—the ultimate, probably in point of swift, personally controlled, flying manoeuvers with no other engine than the human body, and no other control board than the individual mind and nervous system.

|

| Each week end when snow conditions favored, more people came. TUCKERMAN RAVINE, MOUNT WASHINGTON, WHITE MOUNTAIN NATIONAL FOREST, N. H. F-359868 |

UPHILL . . . By a natural coincidence, most of the developing centers of skiing and of other winter sports in this country are on or near the national forests. The first charge of the Forest Service was to protect watersheds, and this is uphill work. The work of ruling water run-off must start at the mountain crests. If you will turn to the map of the United States (opposite page 288) which shows the location of the national forests, you will be able roughly to locate the loftiest parts of the Allegheny barrier, the Continental Divide and the Coast Range by the general grouping of the national forests there.

The same power that moves the raindrop downward is the propelling force of thousands of pleasure seekers, winging down mountainsides today. National forests and winter sports have been a natural combination from the first. The places most favored are generally the highest, where snow seasons are long and where there are likely to be more open slopes. Skis and webs, sleds, and toboggans are no new things to forest officers. They have used them for timber cruising, and in making wildlife estimates and snow surveys, and in other administrative duties ever since the Forest Service was organized.

And so when the boom in winter sports began, forest officers in general gladly welcomed returning winter visitors. Here was something a man could put his heart into more completely than meeting the often querulous complaint of picnickers as to firewood. These youngsters strode forth as if they owned the earth; they were hard and woodsworthy, most of them. They asked no odds and uttered no complaints. Here were men, and adventurers. And it surely livened things up there on the mountain in the wintertime to have them coming in.

Each week end when snow conditions favored, more people came. Interest increased. Winter carnivals became popular. These stimulated local business and encouraged more people to turn out. Soon many came who lived outside the snow belt. Skiing (cross country, downhill, slalom, and jumping), ice hockey, tobogganing, snowshoeing, and various combinations of ice and snow sports were taking thousands up mountains that hitherto were all but forsaken in winter, by the beginning of the present decade.

The innkeepers rejoiced. Resorts, always handicapped by the brevity of the summer season in mountainous and northern locations, began no longer to stand idle all the long months of winter as property depreciation mounted and taxes continued. Heating systems were enlarged, winter quarters were remodeled, the lone winter guard was replaced by a score of employees, and many a new resort especially designed and operated for winter vacationists was built in areas favored by a long snow season.

Throughout the country now the approach of cold weather brings to thousands a lift of the heart, a stir of the energies, more generally associated with the coming of spring. Outdoor clubs look to the condition of their ski jumps or install ski tows. Resorts, department stores, railroads, and winter sports shows begin building up an early season interest. The young army of enthusiasts overhaul their equipment and prepare themselves. Many who were spectators at a winter carnival or on some sports area the year before enroll in preseason schools and are instructed on so-called dry courses. Great arguments as to equipment, techniques, and the proper kind of ski wax arise.

Because of the many different points where winter sportsmen may enter or leave the forests, and because of the limited personnel available to keep watch over them, only estimates of the extent of winter use of national forests now are possible. But winter sports visits exceeded 14 million, most certainly, in 1938. Nine-tenths of this use was on 50 of the 130 forests. These 50 forests lie in 5 States, and the distribution of the winter-sports use ran approximately thus:

On 17 forests in California 639,000 visits; on 7 in Washington 106,000; on 14 in Colorado 110,000; on 13 in Oregon 140,000; and on 11 forests in Utah 88,000.

For the West the total reached 1,182,764. New Hampshire's White Mountain Forest received 69,000 visits. All other national forests, including those of Alaska, took care of around 43,000 among them. And nearly everywhere, where latitude or altitude permit, there is evidence that winter use is not only mounting, but soaring.

FACILITIES . . . All this has led to a reenaction, rapidly, of the dilemmas presented when people first began coming on to the national forests to picnic and to camp. At first forest officers could say, God bless them, and leave them alone. Then less skilled visitors came, and in greater numbers; and soon they had to consider making some rules and providing facilities.

To plan, rear, and maintain winter-sports facilities sufficient to meet the demand presents an administrative problem of considerable magnitude. The first lone winter adventurer gloried in his self-reliance; but an increasing army of novices congregating in favored areas cannot be allowed to freeze, get lost, or break their necks, regardless. Fortunately, the sports most enjoyed by the great mass of winter visitors require only simple facilities, and if these are wisely planned they do not measurably mar the forest atmosphere.

One essential on a winter-sports area is to get the crowds up the mountain and down again, with reasonable safety, after private means of conveyance have gone as far as they can. Formerly, the people came to the forest in special cars chartered by an outdoor club to be shunted off the main line at a winter resort. Now week-end or holiday "snow trains," often running in several sections directly from metropolitan centers, are needed to get the crowds to the snow country. "Snow buses" and "snow planes" are more recent developments operating to some extent in both the East and West.

Most winter sports parties come to the mountain, and part way up the mountain, in their own cars. This calls for keeping roads up the mountain open, whatever the weather; for sizable parking places, cleared of snow accumulations, somewhere near the pleasure slopes and heights; and for further measures of crowd convenience and sanitation.

|

| Most winter sports parties come to the mountains in their own cars. STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST, CALIF. F-344595 |

The push of late years to extend and maintain national-forest and State highways for year-round use has been a major influence in extending winter sports. Foresters selecting winter-sports areas give preference to places that can be reached over roads that are plowed for other purposes. Where this can be done, there is no greatly increased cost of maintenance. But the pressure of demand by winter sportsmen is sometimes such that roads never before kept open all winter are now snow-plowed regularly, and resident families who used to be snowed in most of the winter now can run down into town whenever they please—thanks to the winter sportsmen.

Another development that follows the penetration of active Americans to mountain playgrounds, over sanded and plowed roads, is a following throng of motorists, some spectators, others just motoring—driving up the mountain and down again in winter, as they do in summer, just to be more or less out of doors and moving. Motoring promises, on some such forests, to become in point of participating persons, the leading winter sport there, just as now it is generally the leading summer forest sport.

As the fall winds sharpen on many a forested mountain, the forest guards set border markers, stakes 20 feet high or higher, to mark the winding shoulders of tortuous mountain roads. These stakes serve to guide the tractors that push the snow plows or bulldozers as the snows fall, drift, and deepen, all winter long. Occasionally a marker is covered entirely, but 20 feet is generally tall enough to stand above the snow and guide the plows. By such means the highway to beautiful Timberline Lodge, for instance, a Forest Service resort on the Mount Hood National Forest in Oregon, is kept open for winter sportsmen, their followers, and the local people, all winter long. The construction and year-round maintenance of this beautifully graded highway with its wide spaces for turn-off and for parking, has brought untold pleasure to many thousands of persons.

|

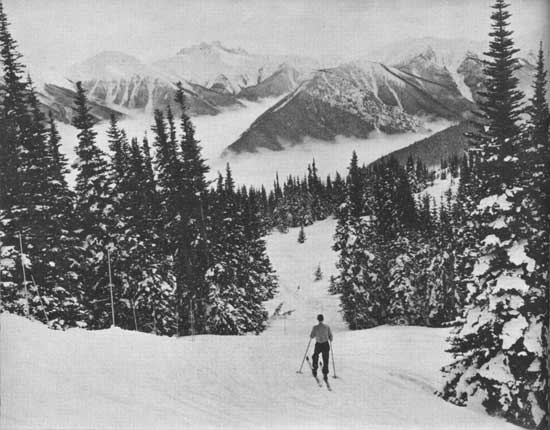

| Ski trails must be carefully planned and developed, with many things considered. DEER PARK SKI AREA, FORMERLY IN OLYMPIC NATIONAL FOREST, WASH. F-359327 |

DOWNHILL TRAILS . . . Skiing is the main sport at Timberline Lodge. Ski-crowd facilities cost something, too. There must be a diversity of facilities to meet varying degrees of skill and interest. Pioneer skiers were able to take things as they found them, in the main. They used logging roads for downhill runs, and tote roads, horse trails, or hiking trails for cross-country travel. In the East, carriage roads leading to popular summits and horse trails constructed to haul material to fire lookouts provided challenging grades and turns. In the West, naturally open slopes, both above and below tree line, and areas selectively logged furnished suitable terrain.

This remains true, of course, of the mountain slopes in many parts of the West, and artificial improvements there are generally unnecessary. On the densely forested slopes of the Northeast ski-trail construction and maintenance is more necessary, expensive, and difficult.

Ski trails must be carefully planned and developed, with many things considered—logical termini, exposure to wind and sun, the risk of accelerating soil erosion. Beyond that, one must consider the trails; do they deface the mountain? And beyond that are questions about bridges, warming shelters, and considerations of sport and safety. What should be the maximum, minimum, and prevailing grade, the frequency and degree of turns on trails, and the total length? Here are problems that have to be solved on no fixed scale, for a novice trail after heavy use and fluctuating temperature may become difficult to the intermediate skier, and heavy snows may make an expert trail safe even for for beginners.

Trails "stiff" enough to excite and satisfy the average skier most of the time, and yet not to break too many bones of beginners—that is the only possible formula, admittedly inexact, very largely a matter of personal judgment or opinion. Laying out ski trails, foresters generally temper the run with constant thought of the novice. There are so many novices and that number, happily, is increasing all the time.

Cross-country skiing is becoming more popular. Each year there are more older skiers whose original interest in competitive skiing turns toward less arduous forms. Ski touring requires clearly marked routes of varying grade through areas of scenic interest and shelters in the "high country."

Cross-country skiing without trails on the snow fields and glaciers in the national forests of the West and of Alaska provides high adventure. But only a few are up to it. Trails with shelters are sufficiently dangerous for most people, and especially for those who have passed their physical prime. And still in increasing numbers unprepared people seek untracked snow in the high country previously known to them only during summer travel, if then. With the possibilities of incurring serious injury or meeting sudden storms in the many truly remote places in the national forests, skiing under such conditions may become extremely hazardous and must be done at the individual's risk. This dispersion from concentration areas is a trend of growing importance. It is hard to say how to handle it. A good many people are getting hurt, and a few are smashed to death, or frozen.

WARMING SHELTERS are more than a public convenience; they are a necessity. They range from primitive, three-sided lean-tos built primarily for summer use and providing little more than a windbreak, to Mount Hood's Timberline Lodge in Oregon where the entire lower floor, known as the ski lobby, is maintained for the free use of winter-sports visitors. Intermediate structures are of various sizes and types to meet local needs and are frequently used in other seasons as well. Such buildings are located where they will give the greatest public service and are designed to harmonize with the landscape. They are constructed to meet the exacting demands of cold-weather use and heavy snow load. In some buildings, only shelter, sanitation facilities, and first-aid equipment are provided. The more extensive structures to furnish other daytime public services, such as refreshments, are usually operated under special-use permit, frequently issued to a local nonprofit organization chiefly interested in furnishing such services as a public convenience.

The problem of furnishing adequate overnight accommodations is being met, in some part, by arrangements which vary with local circumstances. In the Eastern forests such accommodations are usually found sufficiently near at hand on private lands, but in several instances the Forest Service has built "high country cabins" equipped with stoves, fireplaces, and bunks for overnight use. In the West, where the distances between winter-sports centers and communities are greater, some sleeping accommodations have been provided on national-forest lands.

Public interest requires that the winter-sports areas be adequately supplied with miscellaneous facilities—directional and informational and that entrance signs be adapted to winter conditions. Skiers, particularly, are interested in the length, grade, classification, and objectives of unfamiliar trails. Visitors must be warned of general and specific hazards. Snow gages at various elevations are of special interest. Routes marked for winter use are needed by snowshoe and mountain-climbing groups. Loop circuits for dog-sled trips and snow-banked chutes for tobogganing help to round out any well-developed winter-sports area. Ice-covered lakes and ponds naturally clear of snow are ideal for skating, but most national forests are too heavily blanketed with snow to justify the necessary clearing and scraping. Bobsled runs are not provided by the Forest Service because of the abnormally high construction and maintenance costs for the relatively small number who use them.

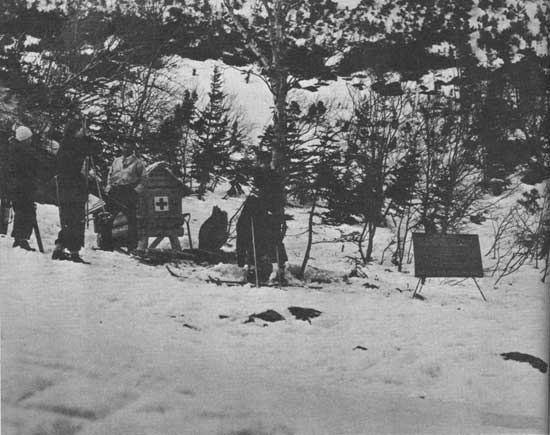

Skiing, tobogganing, and winter mountaineering must be recognized as presenting greater risk of accident than most other forms of forest recreation. At points of greatest danger the Forest Service has installed caches of first aid supplies and equipment for public use in case of emergency. On many forests local chapters of the American Red Cross, winter-sports clubs, and other groups, such as the National Ski Patrol, have cooperated in furnishing medical supplies, first-aid treatment, and instruction. Injuries are increasing. Only complete observance of ski-trail etiquette, a greater interest in controlled skiing, and a widespread recognition by individuals of their personal limitations and responsibilities will bring about improvement.

JUMPS AND TOWS . . . Ski jumps on the national forests vary from natural "take-offs" formed by wind-blown cornices to major ski jumps with artificial towers and graded landing hills. The more elaborate jump is usually constructed and operated by local ski clubs. The Forest Service issues special-use permits when satisfactory sites on privately owned land cannot be found. This is particularly true in the West where much of the higher land surrounding communities actively interested in this form of winter sports is on the national forests. In the East, there are generally plenty of natural sites for ski jumps on privately held land. Nowhere has the Forest Service, itself, undertaken to develop spectacular ski jumping or to promote tournaments. Tournaments are all right, but they should be conducted with private money. The equipment costs too much; it is used too short a time each year; and the personnel and maintenance cost runs too high to justify the Service setting up winter-sports hippodromes on its mountain sides.

|

| At points of greater danger the Forest Service has installed caches of first-aid supplies and equipment for public use in case of emergency. TUCKERMAN RAVINE, WHITE MOUNTAIN NATIONAL FOREST, N. H. F-351351 |

To keep things simple, and as safe as possible; to give people a chance to slide and leap and exercise, themselves, rather than simply to stamp, hover around fires, and watch experts do so that is the aim and policy. But people in general in this day of the motor do not like to walk uphill, and the sport of dashing down the mountain need not always now be paid for by the toil of trudging up. All the richer resorts have ski tows, and on many forests, from New Hampshire to Oregon, the not-so-rich are developing and installing ski tows of their own.

A ski tow, in effect, is a low-slung cable coil turned by a motor. An engine out of the oldest of cars can keep a simple ski tow going, barring breakdowns. The skiers take hold of the lower sag of the cable, and up the mountain side they go. Some of the ski tow outfits installed by little local sports clubs on the national forests are as much an expression of native genius and inventiveness as were the first car trailers. They do not cost much; they give a great deal of pleasure—both in their construction and in their use. But it must be admitted that none of them is beautiful, or harmonious with the forest atmosphere.

The revolving cable loop propelled by a discarded automobile engine soon becomes, in richer resorts country, an apparatus refined with chair lifts. It will be interesting to see how long it takes to bring in overstuffed leather chairs. The present policy of the Forest Service is to permit local clubs to install simple tow rigs, and some few permits have been issued to special-use commercial operators who agree to erect their equipment in inconspicuous locations. As an ingenious and effective supplement for fixed tows, an over-the-snow tractor or "sno-motor," which plods uphill towing a spacious sled, has been developed and demonstrated by the Forest Service, and the idea is making headway. These are not permanent installations; that is another good thing about them. If the particular winter-sports area under development does not last, the tractors can waddle on to another area the winter following, and work there. In any event, the rig is free to get out and do all sorts of useful work elsewhere both during and between the snow seasons.

|

| The skiers take hold of the lower sag of the cable, and up the mountainside they go. BERTHOUD PASS, ARAPAHO NATIONAL FOREST, COLO. F-344899 |

LIFE AND LIMB . . . As a people, we love speed—thrill, dash, zip. We are not in general a cautious people. Examine our record as motorists the slaughter is awful. In most States you have to be examined and licensed to drive a car now; but any daring idiot, young or old, can put on a pair of new skis, be towed to some precipitous mountain height, shut his eyes, take a dare, and take off.

Deep snow is softer, by far, than a paved highway, and the general concentration of ski traffic on our national forests still is such that smash-ups usually involve only one person at a time. To dare, on one's own power only, a broken bone or so is not a bad idea, entirely; often it leads to releases more satisfying and less permanently damaging than sassing the boss and getting fired.

But forest officers have many other things to do than take down the mountain the physically wounded who could not wait to learn on practice slopes and courses; who want to do what the newsreel showed, right away.

"Take it easy, at the start," is an experienced forest officer's advice. "Feel your way along. Don't take dares your own, or any one else's—until you feel sure that you can run the course triumphantly. Get the feel of the thing gradually. Before you step off cliffs with wings on your feet, learn how to use those wings. Stay on the practice slopes, away from all the spectators. Never mind if the boys who have had 2 years of it call them nursery slopes. It is the second-year crowd who crack up most often and hardest. Take the counsel of the older skiers. Take it slow and easy at first and enjoy yourself."

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap7.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |