|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part Two

KINDS OF OUTINGS

Chapter Six

Camps

During 1938 more than 30 million visits were made to national forests. Excluding sightseers and those simply passing through, approximately 14-1/2 million of these visits were by people who stopped on the forests for recreation.

Many forest visitors stop at hotels, summer resorts, and dude ranches. Others go to summer homes built under special-use permits. But most national-forest visitors head for campgrounds equipped with fireplaces, pure water, and simple but sanitary conveniences. There are now more than 3,500 of these developed campgrounds in the national-forest system. The CCC has been a big factor in developing campgrounds, and roads and trails leading to them.

Annual Report of the Chief, Forest Service, 1938.

BY A CLEAR FAR CREEK on the Choctawhatchee National Forest in Florida is a small clearing which seems at first sight to contain nothing humanly useful. But there is a camp here.

It is a poor but beautiful forest, the Choctawhatchee—pine, scrub oak, and palmetto growing mainly in deep sand. On occasional strands of hammock land which reach out into the still, bright waters of Choctawhatchee Bay and its dreaming bayous, there remains good timber—virgin stands of straight, clear pine, wide-spaced. But most of the forest was pretty badly cut-over and turpentined-out while in private ownership. Since it became Government property it is healing, but at the same time it must yield sustenance for a resident or nearby population of some 1,500 persons. At present it yields a fearfully thin living, largely because of the thinness of the soil.

|

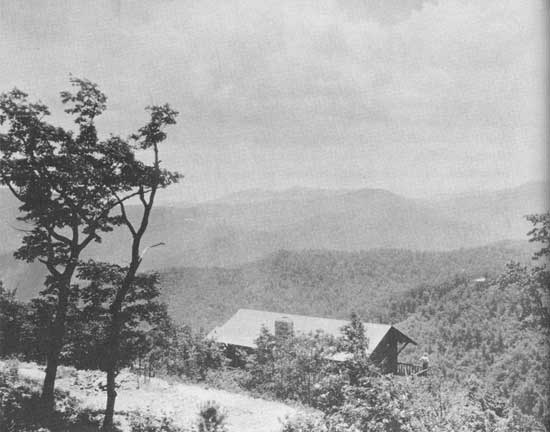

| There are hillsides which are suited for no forms of intensive use except summer homes. PISGAH NATIONAL FOREST, N. C. F-238076 |

It is in dry, not in wet, weather on the Choctawhatchee that your wheels get to spinning and your car slides and stalls. The soil of Camp Pinchot, the original ranger station of the forest, for instance, is so coarse and thin, so like the beach, that a grass,1 native to the Manchurian Desert, was planted to provide a binding cover there. The loose-sand roads of the forest are not certainly passable for cars and for fire-fighting equipment unless clay is hauled in and mixed with the sand as a binder. At most of the fire towers and at the present ranger station, there are native-ornamental plantings, and some of the forest guards have subsistence gardens, to the end that they may eat. But the gardens and plantings are literally "made," on soil or muck hauled in by the truckload with CCC labor, and mixed as topsoil with the sand. A recent survey on the Choctawhatchee Forest shows that the white man who makes $550 a year there, or the black man who makes $425, makes more than the average.

1Manila grass, Zoysia matrella.

All this has a bearing on the recreational facilities we shall find in that apparently useless clearing on the creekbank when, in a moment, we return to it. Campgrounds of the Forest Service may seem at first glance somewhat standardized the country over, but there are endless differences between them. No two of them are alike, any more than two trees are alike; for like the trees, national-forest campgrounds are the growth of a given soil, shaped by the immediate native background, and often modified in their form and structure by immediate need.

Here on the western Florida Gulf Coast what have the forest dwellers left by which to live? Timber, yes, and better timber is coming back under selective management. This takes time, and never again, in all likelihood, will this stretch of country support so many people as during the great timber-cutting era here. Naval stores, yes, but except on the national forest that is a diminished resource, decidedly; and under the generally prevailing methods of overbleeding the pines, many of the native turpentine operators are killing off what is left.

Fishing, possibly; the Gulf and bayous are said to be teeming with fish, but the relatively few residents who follow the water seem to be getting about all of the small living there is in salt-water fishing for this forest population now. Sport fishing may be improved, however; lakes have been stocked. Later, there may be call for guides to take sportsmen to these fresh-water lakes, just as there are guides and skippers to take out Gulf fishing parties in summer weather now.

The more closely you examine the situation, allowing everything possible in the way of an improvement of agriculture on a sound base, allowing everything that may soon be expected in the development of forest industries utilizing wood pulp, the more plainly it appears that the principal usefulness of this forest for the next many years, and the main support of its people, will be recreation based on scenic beauty, its generally agreeable climate, and its game resources. Game, it appears, will be especially important.

There is rather brisk summer-tourist business here now along the western Florida Gulf Coast. It is mainly an exodus of middle-class people seeking relief from the dense, humid heat of summer in the interior country immediately to the north and west. Over on this low shore Gulf breezes keep moving most of the summer and the summer nights are generally cool. Visitors attracted by the Gulf winds probably bring more money to the residents of this forest and of the towns adjoining than all their other products combined. But such money blows in only during the summer vacation season, in any quantity; from May to October, in the main. During the rest of the year most tourists push on southeast to the warmer, steadier sunshine and the great human swarms of Florida's peninsula beach resorts: St. Petersburg, Sarasota, Palm Beach, and Miami, particularly.

In point of outdoor sunbaths and the rather gaudy diversions of the Florida beaches, this more northern and western Gulf Coast country cannot compete as a winter playground with peninsular Florida as a whole. It now attracts a sparse scattering of hardier winter refugees from overcongestion and mounting prices on the peninsula; that is about all. And yet the bayou country of the Choctawhatchee and its environs has, for some, winter attractions which are incomparable. It has a bracing, swiftly changing winter climate, springlike to a northerner, much like Maryland's April and early May. It has openness, and space, and a relative solitude to offer. To the naturalist it offers for pleasure or study an amazing range of hardy vegetation, and on both its placid shores and wide, shining waters, a returning wealth of wildlife.

Wildlife; that is the Choctawhatchee's great natural crop, and the main hope of its residents for the future. The game has been protected, with short open seasons of specified shooting, mainly in the off-peak season of vacation usage. Game population is being built up to a point where more liberal limits, especially in winter, may be allowed. Ducks now are thick on its bayous, and generally so tame that one can get to within a stone's throw of them to take their pictures. Deer have increased to a point where soon a lifting of present limits will be required to sustain a natural balanced husbandry on this forest. Coveys of quail are multiplying, too; in some places they are so tame that they can be seen running and darting across openings, and vying for food with the lean, sharp-snooted razorback hogs still left to range freely by their owners on this forest and in its adjacent poverty-stricken towns.

If one is not by nature a hunter (and the man who writes this note of comment is not), the prospect of the Choctawhatchee becoming soon an important and fruitful hunting ground, with an augmented income coming more steadily all year round to its needy forest residents and townsfolk, will exert no overpowering emotional appeal. One might prefer, emotionally, to keep it as it more or less is, a refuge, forever. But practical considerations enter and enter most urgently, and it is conceivable that in many places like this, with schools (especially the schools of the Negro residents) and hospitals and diets and living standards as they are, hunting will have to be fostered and encouraged to add to the food supply, but principally to bring in tourist money. Native stocks of people are more important to preserve than game. And with proper management, both kinds of native stocks may be better sustained.

"Look at that," says a forest officer, disgustedly, seeing crude barrels of naval stores drained from overdriven trees, bumping in big trucks out of private lands within the forest. "Draining their lifeblood away!" Later, down on the firm sand of a beautiful point of beach, with woods behind it, he points with delight to the sharply cut tracks of a big buck; and, "That's going to be their main living, the folks on this forest!" he says.

HUNTING CAMP . . . It is natural, then, that when foresters on the Choctawhatchee think of recreation, they think first of all in terms of hunting, and it is natural that the first developments toward forest recreation here were inexpensive, simple hunting shelters. They make them better now than they did at first. For at first they had no landscape and structural architects to guide them, no appropriations whatsoever for materials, and no relief labor to do the work. This shelter in a clearing by the creekbank, just completed, was planned by a Harvard graduate in landscape architecture, traveling out from the Tallahassee office over all the Florida forests, and the local ranger saw to the actual construction of the job. It is a good job. It fits into the scene so completely that a visitor is well into the clearing before he sees it. And when he does see it, he feels at once that it is all right there; it belongs.

Built of native timber by CCC labor, this shelter cost under $50, and is so well and plainly constructed that the ranger figures there will be no appreciable depreciation (short of fire or acts of vandalism) in its usefulness to the public for the next 20 years or so. An adaptation of the Adirondack type of open-front lean-to (no longer widely favored on most forests with harsh climates), this low, dark-colored building is just about wide and deep enough that six tall men may sleep in it if they all manage to turn over at the same time. Before its open front is a fire mound, hip high, made of logs and sand. Hunters are encouraged to build their fires on this mound.

The wooden lean-to, a fire mound, a convenient toilet, a shallow-well pump, a rack of firewood raised from the ground is all there is to this hunting camp, and it has been getting plenty of use. If more sportsmen show up than the camp can carry, the others simply make throw-down beds and build pit fires nearby. This is permitted on the Choctawhatchee by the simple procedure of getting a campfire permit from the ranger.

There has been some doubt among Florida foresters whether to install at these small and isolated hunting shelters a combination bulletin board and folding field desk, an all but standard piece of equipment at larger Forest Service camps. Experience shows that many passing users of these hunters' shelters do not like to register. They see some catch in it, or they are not in the registering mood. They sign fantastic names and enter in the register remarks often amusing but not always quotable in the presence of ladies.

No sooner were these hunting camps set up, however, in the remoter depths of the Florida forests than a secondary use for them developed, as picnic spots. Floridians are great picnickers. In recognition of this urge the Service has prepared beautiful and rather modern forest picnic grounds on all four Florida forests. The one at Little Bayou, near Fort Walton on the Choctawhatchee, is a natural jewel of a picnic spot, accessible by paved road, yet removed from traffic, with a multitude of individual sites so scattered as to allow individual or group seclusion. It is rather heavily used in the hot season. In the summer the hunting camps are not in use, and the picnic parties make their resolute ways there, plowing surging cars through the deep sand.

So now at many of these small camps the foresters are also rearing sizable but inconspicuous rustic shelters, stoutly roofed, but open all around. These structures, too, are built from the native materials of the forest and designed in accord with the immediate forest background and need. They serve as crowd umbrellas. The picnickers take shelter under them during the abrupt torrential rains. Even a small roof gives women, especially, a measure of comfort when the sky opens and rivers fall from the heavens with thunder and lightning whipping and crackling around.

All this is intended seriously to suggest that while equipment and method must accord with a definite policy of forest recreational management, individual adaptations within the limits of policy are permitted and even encouraged, region by region, forest by forest, and by camp—afield.2 This is both necessary and desirable. Every ranger district is different. The ranger there is expected to know policy, and he is credited also, as he gains experience in the Service, with a close working knowledge of that soil, its cover, its weather, and its people. If he proves to lack in any important particular, another ranger takes his post. And so it is right up through the decentralized administrative structure of the Forest Service, in respect to recreation management, timber management, range management, water management, fire control, and everything else. The man on the ground is put there to administer policy, but is given his head as to the details of management, in the main.

2The latest and more concise statement of this policy is appended on page 287, Appendix.

In the planning and administration of forest camp sites, the need of a considerable individual leeway enters constantly. The reasons have already been suggested. There are some 3,800 different forest camp sites already established on the national forests, and more are being opened fast in response to need. You have seen in the description just given one of the newest, the simplest, the least complete in the sand-and-bayou semiwilderness of western Florida. Have a look now, 1,500 miles or so to the north and east, at one of the largest, and perhaps the hardest to handle of all the Forest Service's free public campgrounds Dolly Copp Forest Camp in northern New Hampshire.

DOLLY COPP FOREST CAMP was a commercial resort of the summer-rooming-house type long before forest reserves were created, and long before these were renamed national forests and foresters were charged to administer them for multiple use. But Dolly Copp knew a hundred years ago what multiple use was when it came to mountain air and forest recreation, and getting a living out of that ground at the same time. A pioneer White Mountain woman, she was pioneer also in one of our greatest national industries, the outdoor recreation business. She was a feminist, too. The story of her life is an oft-told legend among White Mountain people today and the facts appear to be well established.

If Mrs. Copp could come back and retrace her way up Pinkham Notch now, she would marvel at our progress. Hard black roads, beautifully graded, strike up nearly every major notch in the White Mountain barrier now. This mountain borderland between Maine and New Hampshire has become one of the most heavily used resort regions in the world. The White Mountain National Forest embraces more than 708,000 acres in Maine and New Hampshire. The 37 State parks and 113 State forest units, ranging in size from 2 to 6,000 acres, run the total area of publicly administered pleasure ground in New Hampshire up to more than 775,000 acres.

But this protected and managed acreage, larger than the entire State of Rhode Island, is by no means a solid, unbroken strip of mountain country. The State forests and parks, with their 11 developed fresh-water bathing beaches, their 15 camp sites, their 19 picnic places, are rather widely scattered. And the White Mountain National Forest, with its 17 developed forest camps and picnic grounds for motor travelers, and its 308 miles of scenic highway, protected from billboards and other commercial encroachments, is widely and generally broken into by private holdings.

As you drive up through that gorgeous mountain country now, up through Franconia Notch, Pinkham Notch, the climbing highways descend at rather frequent intervals to the aesthetic level of U. S. Highway No. 1, between the cities of Baltimore and Washington, say—at its worst. Billboards and hot-dog stands; playful little signs that shriek for you to GO SLOW, else you miss some of Auntie Bessie's Yum-Yum-Yum Cookin'; wayside tourist cabins with names like Dew-Kum-Inn, and Little Rhody—there they are.

Some of the newer cabin camps are quite decent and comely. Some of the private resorts have manifestly tried to follow the practice of the forest in keeping signs keyed down to a quiet tone. On stretches of road traversing private land, here and there, the commercial babble, the blatant aiming at one's eye, pawing at one's arm and purse, has been individually recognized as an indecency, in such a site, and has been somewhat moderated. But too many stretches of mountain road that traverse private land here toward the most majestic heights of the White Mountains in staid New England, are rimmed with shouting greed, shameless ballyhoo, and a desperate ugliness and confusion.

If this were a more cheerful desecration, it might be easier to understand. But it is, for all its clamor, cheerless, insincere shame-faced. It is a sad desecration. Most of the private-resort proprietors, native and transient, great and small, do not really want to carry on like this in order to make a living here in the mountains. You can talk with them and find that out, easily.

Forget it for the moment; put it out of mind. It's too bad that cutthroat competition and the introduction of more decent standards of outdoor recreation should arouse such fierce growing pains in what begins to be our greatest industry, but the result in the end may be beneficial, and the industry will survive. The growth will come from its sounder parts. The pirates and panderers are killing their part of the game, anyway, themselves. Americans are rather patient suckers in the mass, but not eternally so, only for a while.

Let us, as many of them are doing, drive on. The car, climbing rapidly the smooth upswinging road, passes a portal post quietly announcing reentrance to the White Mountain National Forest. The racket subsides. Peace falls again on the eye, ear, and spirit. The road climbs smoothly on now through still woods, clean and beautiful. And it may be that what you take for primeval forest far extending is really only an undisturbed roadside or buffer strip. For this national forest, like all 161 of them, is subject to multiple use. A considerable native population that does not draw directly on the tourist trade must keep right on making a living here—lumbering, woods farming, stacking and shipping pulpwood; or gathering wild ferns, shipped and stored on ice, to provide a natural frame for the hothouse flowers which many other workers in the urban floral trade make a living selling, all through the winter. The products of the national forests are widely diversified. The problem is to see that one use does not get in the way of the other and spoil the resource. These roadside or buffer strips are designed to preserve the scenic value of the resource, and even to enhance it in places. Here and there where the view is especially gorgeous, landscape architects have selected and CCC boys have opened vistas through the woods, and the traveler may look across countless miles upon great ranges seemingly undisturbed.

The 17 developed camp sites on this forest take various form from the nature of their location and are of widely varied sizes, according to the expected use load. Some of them far off the main beaten roads provide only from 6 to a dozen sets, each secluded from the other, around some protected water source, with some sort of jointly used toilet facilities, unobtrusive in design, nearby. A set is a parking place for a car, with tent room, a large open-air fireplace with a cooking grate, and a combination outdoor dining- and living-room table, with fixed benches. These tables vary greatly on both camp and picnic grounds the country over, and the set or outdoor apartment is variously arranged around them, as furniture is in rooms of various shapes.

In all, the Forest Service has installed 23,000 overnight camp sets on its 161 different forests, and 30,000 picnic sets with no special provision for overnight camping. This sort of camping is more or less only a protracted picnic anyway, so it is practical to throw the figures together, and say that on the 161 national forests there are now some 53,000 free outdoor recreational sets, not nearly enough to supply the thronging demand.

These 17 national-forest camps in New Hampshire offer 2,000 sets, between them; and of this number Dolly Copp Forest Camp, alone, has 1,000. Dolly Copp, at the height of its season, is probably the least peaceful national-forest camp in the whole country, yet people keep flocking there and liking it more and more. The camp population from June to September runs around 74,000 for the season. The problem of its administration is fairly comparable with that of the administration of a boom town, and when the more or less resident throng is swelled by holiday transients, squirming for a swim or a day's outing, the scene and situation are not entirely idyllic. Last year's (1938) Labor Day crowd at Dolly Copp totaled 2,600—a peak. "It was like Coney Island without the chute the chutes," says the resident forest guard.

But here as elsewhere, Labor Day usually brings the peak load. There is no time of the year more gracious and wondrous than the fall months here in the White Mountains. September and October bring, to be sure, their bursts of chilly rain, but most of the time the air and sunlight are sparkling clear, and the colors of the foliage are indescribably beautiful with the brilliant reds and yellows in the intervales contrasted with the fresh white snow on the upper slopes. The maximum coloration, in point of brilliance, comes generally during the first week of October. Special tours are formed then to view the height of the spectacle. But to many the best time to be here is after that, with the colors dimming, hazily, and the tourist-load on these mountains so thinned and scattered as to be hardly noticeable. There are, moreover, practical considerations to support the choice of a late-fall vacation. The rates of resorts are generally lower, and the free camps are uncrowded. In many places they are almost unoccupied from Labor Day until winter sets in.

THREE PARTIES . . . Of the three parties lingering at Dolly Copp Forest Camp this sharp September evening, one has tentage, one has a combination tent-and-trailer outfit, and one has it rigged to sleep in the back of the car. The last is unusual, but the practice is increasing. Trailers, too, are somewhat out of the ordinary at Dolly Copp, and at mountain camps everywhere; the real trailer swarm is found generally on flatter lands and along straighter roads, as in Florida. Most forests elsewhere report a general diminution of trailer outfits during the past few years.

The man with his bed in the back of his car is a retired blacksmith from New Mexico. He travels alone, and has been traveling so, and camping, for the better part of 5 years now. A leathery, taciturn, but entirely friendly citizen, 48 years old, he spends his summers north, in New England and the north woods of the middle country; generally has a whirl at Florida and, returning, camps for the late winter and early spring on the desert of his home State, New Mexico. "I've got a little money in the sock," he says. "Nobody looks to me for a living. So it just occurred to me that I didn't have to work any more and could travel around and see the country. It's a good life. I like it." He carries a small tarpaulin to shelter his dunnage, outside the car; and strings this up as a shelter in hot weather. But his home is the car. Its interior arrangement makes even a Pullman berth seem wasteful of space. The gun rack, for instance, lets down under the bed at night; and his whole camp is as neat and handy as a good wife's kitchen.

The tented party is a mother and three sons, aged 8, 11, and 16. They are from Virginia, and are just completing a swing that took them to the Southwest, California, the Northwest, and East again by northern routes.

These are rather well-to-do people, one gathers; the mother has traveled abroad; her accent is cultivated. The boys are all as friendly as can be, but a certain well-bred aloofness tempers personal disclosures at first. This diminishes as evening falls and the fire burns higher. Father, you learn, is at his business back in Richmond. He and Mother wanted their boys to see their own country, the great West especially, this summer; and this was the way it could be done. "Really, you know," says the mother, "it's amazing! One can't imagine! Such size, and vigor, and friendliness, and so inexpensive, if you stay at camps." "A fellow doesn't know what the United States is until he gets over the mountains," says the 16-year-old son.

The three camping parties are bunched together; their shelters almost touch, at the very center of great, bare, Dolly Copp Forest Camp. "It's friendlier that way," says the stout, earnest woman of 50-odd, traveling with her 18-year-old boy. "We camped up in the edge of the woods when we came here. The camp was so full then. But when the crowd went, we moved down here."

The arrangement of the shelters is rather more than an instinctive huddle. Such grouping enables these campers to share cooking fires and trade little chores with each other, daytimes. But at night they make separate fires and sit apart, as a rule.

This third party, the mother and nearly grown son, are from Los Angeles; or that, at least, was their last point of fixed abode, while the boy finished high school there. His father is an Army engineer on duty in China, but due to retire on retirement pay in the autumn of 1939. The whole family lived in China for a while, but conditions did not favor that arrangement, so the boy and his mother returned to the States. He did well in science and in high-school journalism, and was through with high school at 16, but not well. "He had grown too fast and burned his nerves, he worked so hard in school," his mother says. "I was worried about him. And he didn't know what he wanted to go on and do."

"All I knew was, I wanted to get outdoors and stay out," says the boy. "And Mother, she likes that, too."

So his mother closed their little curio shop with its gay-colored umbrella, which is a colorful part of their camp equipment now. She paints and sells china and small decorations. The boy built a short two-wheeled trailer, and fixed it skillfully, so that the china and painting materials could be packed. They took to the road together, 2 years ago last August. They have been about everywhere in this country since then. The boy has gained 15 pounds, and is strong and self-reliant. He and his mother have camped in forests and parks from the Grand Canyon to Canada, from Florida to Mexico. The boy had developed a definite talent for sketching. He likes to sketch wildlife, especially. He knows what he wants to do now—forestry. He and his mother are stopping at different colleges on this swing, looking them over, getting ready to set up a home again, where the head of the house will join them, while the boy goes on through college. They are not quite sure yet what school it will be. They are going to have another look at various colleges on their way south this year to the Ocala Forest in Florida, where there is a winter trailer camp.

Having heard all this the forester gives them a note, penciled on a page from his notebook, to his former university teacher of forest conservation and agricultural journalism. "You see! I knew you'd find help when the time came!" the mother exclaims.

SUMMER HOMES . . . Many families who come to the forests for vacations want greater permanency, greater comfort, and more isolation than campgrounds offer. The Forest Service has for years issued permits giving individuals, exclusive temporary rights to build summer homes on small tracts of public land. The sites, in the main, are carefully selected. The permittees are required to comply with approved building plans, with permit conditions, and to see that all developments are suitable to the forest. Few people can afford a summer home in the forest, and the exclusive use of land for home sites is not, as a rule, allowed to compete with other forms of recreational use. Campgrounds, picnic grounds, and other developed areas for use of the general public usually require fairly level ground, and there are often hillsides suited for no forms of intensive use except summer homes.

Holders of summer-home permits are encouraged to form cooperative associations. These associations, whether in groups or scattered, can provide community docks, boathouses, water systems, telephone and power services, and buildings for community meetings, which the individual could not afford. Permittee cooperatives cooperate in such matters as watchman services, delivery of supplies, and fire protection. Associations also afford a medium through which forest users can advise the Forest Service of their needs and by round-table discussion arrive at an amicable solution of common problems.

SEELEY LAKE lies 50 miles from Missoula, Mont., in the Lolo National Forest. It is a small lake, 1/2 mile wide and 2 miles long, located in a wide, timbered valley surrounded by high peaks of the Swan and Mission Mountains. Around this attractive forest lake has grown a recreational center typical of hundreds of others around lakes, along streams, and in forested valleys on national forests.

|

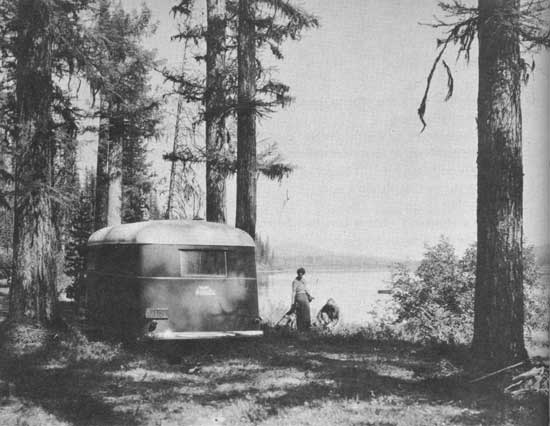

| People from distant States sometimes come up to the camp for a day or week's outing in tent or trailer. SEELEY LAKE CAMPGROUND, LOLO NATIONAL FOREST, MONT. F-350569 |

Many families, mostly from Missoula, have spent their summers here for more than 20 years. These people are a representative cross section of western town doctors, lawyers, university professors, businessmen, and their wives and children. Perhaps 30 summer cabins, modest structures and simply furnished, have been built on selected locations near the lake, all under permit from the Forest Service. As soon as school is out in June, the people move in and often do not return to the city until the end of vacation. The youngsters swim, boat, fish, ride, and explore together, while the older people fish or putter about, or just relax. There are no formal social duties to attend, no obligations to pay, just visit or receive company as they wish.

On a fine point of land jutting into the lake is a large public campground set in a forest of old tamaracks. Fireplaces, tables, and benches are available for picnicking or overnight camping. People from distant States sometimes come up to the camp for a day or week's outing in tent or trailer camps; mostly the forest campground serves people from the nearby valleys. There is an organization camp, used all summer by the Boy Scouts, Campfire Girls, or other groups. Across the lake is a hotel under permit from the Forest Service, and at the end of the lake, on private land, is a store and cabin camp which also provides dancing for those who desire it.

Some of the summer cottagers keep saddle horses for riding on the forest roads and over the back-country trails. Occasionally more ambitious trips are made; once each summer a 2 or 3 weeks' fishing and exploring expedition is taken into the high peaks of the Mission Mountains or to the far reaches of the Flathead and Sun River Wilderness Areas. The boys, and even a few of the girls, learn to throw the diamond hitch and to care for themselves and their horses on the trail. When the duck season opens in the fall, several of the cottage owners return to hunt migrating wild fowl on the string of small lakes extending up the valley. In midwinter, after the snow is plowed out of the road, gay parties drive up from town for a few days of skiing and other winter sports.

DEVELOPMENTS . . . The origin of the national-forest movement in this country goes back to the third quarter of the nineteenth century. Concern over destruction of watershed and commercial forest values by uncontrolled, ruthless private exploitation, and the recognized evils of wholesale, deliberate, and easy passing of the public domain to private ownership, led finally to passage of the act of March 3, 1891, authorizing that the "President of the United States may, from time to time, set apart and reserve, . . . in any part of the public lands wholly or in part covered with timber or undergrowth, whether of commercial value or not, as public reservations. . . ." This act was clarified and amended by the act of June 4, 1897, which gave a very broad grant of power to the Secretary "to make such rules and regulations and establish such services as will insure the objects of such reservations, namely to regulate their occupancy and use, and to preserve the forests thereon from destruction."

Early national-forest objectives and management were necessarily utilitarian, attuned to the needs of the time. No one could have foreseen then the place which recreation was later to take. The western national forests were established in regions yet in the pioneer state of development. For a good many years the pressure of work, coupled with slowness of travel and lack of accessibility, resulted in but a small volume of recreational use, and that for the most part local.

Some idea of how fast the thing grew may be gained from notes lately gathered on the Apache National Forest—some 1,700,000 acres of mountains above desert, of which about a million acres are in New Mexico, and the remainder in Arizona. It is thought that the Coronado Expedition crossed this forest. Mexican settlement of the country did not begin until about 1872, and after that there came Mormon pioneering, but hardly anyone went there for pleasure prior to 1900.

As a national forest, the Apache is 41 years old. There are 350 miles of trout streams on it, and a considerable abundance of deer, elk, antelopes, bears, mountain lions, wildcats, squirrels, and turkeys.

Hunters sometimes entered the Apache, but the first recorded tourist dates from May 1, 1912. Down the road from New Mexico that morning came a Mr. Baker driving the first automobile ever seen in Springerville. Amid general excitement he purchased gasoline (50 cents a gallon), had his lunch, inquired of roads, adjusted his duster, and started on his way, but not before he had signed the register at a local mercantile company. By 1919, cars were no longer an oddity. More than 6,000 were registered in Arizona alone, and travelers, the business people reported, "came from everywhere and were destined for every place." State highway flow maps indicate that well over 30,000 "foreign" and some 45,000 Arizona cars pass each year through Springerville now.

Visitors to the Apache Forest exceed 50,000 annually. Of these, some 35,000 are "en routers," passing through. Of the total, about 1 in 10 lingers long enough to enjoy the scenery, the climate, or the stillness; and slightly fewer than 1 in 10, around 4,000, stay an average of 7 days, fishing, hunting, or camping. There are now 17 camp and picnic sites on the forest, 230 miles of forest highway, and another 400 miles of forest development roads.3

3Forest highways are built primarily for the use of people living in and adjacent to the national forests, or as part of the general highway system. Forest development roads are built primarily to facilitate use of the forest resource and for the use of forest administrative and protective forces.

What happened on the Apache happened as rapidly, or even more rapidly, and with much higher concentrations of use, on many other forests. And as more and more people came, an important change developed—important from the standpoint of forest administration.

Virgin lands for recreation were no longer near at hand. More and more people seeking wilderness lands turned toward the national forests wherein, in many parts of the West, are the only remaining wild areas. And the character of the forest visitors and their habits changed rapidly. The capable, resourceful, outdoor-pioneer type soon was outnumbered by men and women with less woods experience. Accustomed to more urban surroundings, the newcomers were much less woodswise; they did not so much delight in roughing it. This change did not take place in 1 or 2 years, but the rate of change was so great and the increase in volume of use was so large that recreation, as a forest use, began to require special facilities and assume the status of a major activity on the national forests much more rapidly than had been anticipated.

Data for the years 1905 to 1914 are not available for all national-forest regions, but the North Pacific Region in 1909 reported 45,000 recreation visits to its forests and the Rocky Mountain Region reported 115,000 the same year. It is interesting to compare these figures with the 1,507,000 and 1,785,000 visits, respectively, made to the same forest areas for recreation in 1938.

In 1911 Congress passed the Weeks Law which authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to purchase lands necessary to protect the watersheds of navigable streams. Shortly after that date, the purchase of lands and the establishment of national-forest areas was initiated in Eastern States Since these purchase units were close to centers of population, they were used for recreation from the first.

The early use of the forests in all portions of the country by city people required some attention by forest officers. Every visitor increased the fire risk and in areas of concentrated use sanitation soon became a problem. The policies evolved to safeguard the forests from fire and to protect the public health were simple public use of the forest areas was free with the fewest possible restrictions. Early practices consisted principally of a simple request: Visitors were asked to "leave a clean camp and a dead fire."

Forest rangers took time to clear imflammable material from around heavily used camp spots and to build crude rock fireplaces. They erected toilets and dug garbage pits whenever materials could be obtained. They developed and fenced sources of water supply for campers. They made and put up signs to guide people and caution them about care with fire. Congress made no appropriations for such special needs for many years but ingenious rangers fashioned camp stoves and fireplaces of rock, tin cans, and scrap iron; tables, toilets, and garbage pit covers were made from lumber scraps and wooden boxes; and crude signs were painted and displayed on rough-hewn shakes. Many of these earlier improvements were raw looking and some of them were clearly out of place in the forest environment, but they filled a real need.

At first, most of the field force was beyond its depth on questions of recreational planning. They needed help by the time the specialists came along. The demands the field now makes on the specialists' time and energy give constant proof of it. But there are fairly constant and natural differences between the way a ranger, for instance, looks at a camp or picnic ground and the way a landscape architect looks at it. This question of swings, sand boxes, and seesaws for the children is a case in point. These child coops are ugly; they look out of place in most forest backgrounds; and they are especially ugly and especially out of place when, as generally happens, the forest officers install the sort that are made of metal—the standard equipment seen on so many city playgrounds. But, as the rangers and forest guards insist, people come to the woods to get some rest, and what rest does a mother get if she's retrieving her young every whipstitch from running off, getting lost, and from possible encounters with rattlesnakes and wild animals?

When a 5-year-old child was lost and killed on a New Mexico forest one winter, practically every officer on the forest pointed out that this might not have happened if the children had been given a safe place to play on that forest site, while their parents rested. All right, then, says the landscape specialist, have your swings and seesaws if you must. But make them of native materials, not of galvanized pipe but of timbers. Some forests have done this, but there is no known way to make such swings as permanently strong, as little likely to break and hurt somebody after the wear and tear sets in. And the architect must also consider, the resident foresters point out, that such swings are often used by boisterous adults, a couple of 200-pounders at a time, maybe, standing on them, swinging like fury, there in the woods. So iron-framed swing brackets and chains for rope are still one of the ugly urban refinements permitted on many forest camp picnic sites. Playgrounds are set off as remotely as is consistent with safety, however, and hedged with native vegetation to preserve the forest atmosphere.

Most of the refinements which have been brought into forest recreational sites and structures are far more comely. There has been a vast improvement in this particular during recent years. Until about 1914, administration of the recreational use of the national forests had been wholly in the hands of the field force. The effort was still so small and so scattered that the need for a national policy was not evident. In 1915 the first preliminary study was made by a member of the Chief Forester's office. In 1916, Frank A. Waugh, professor of landscape architecture of Massachusetts State College, was retained to make a comprehensive survey and report.

Public demand was analyzed. Plans were made for several important areas, such as the Mount Hood region in Oregon. In an effort to improve hunting and fishing, the first game refuges were established, and efforts to restock fishing streams were launched.

Then came the World War, and all activities not absolutely necessary to protect the forests from fire and for the production of wood, minerals, meat, wool, and leather were curtailed. Many foresters enlisted in the American Expeditionary Forces' forestry regiments and other branches. For 3 years, which were exceptionally bad forest-fire years, a greatly reduced field organization did the best it could on our national forests. Little or no attention was paid to recreation until 1920.

THE RUSH OUTDOORS. . . That was when it really started, after the World War. Prior to our joining the conflict, the San Francisco Fair of 1915 a vigorous promotion of national parks, at their outset, had stirred perceptibly stronger tides of travel westward; but these tides lapsed as eyes strained eastward and all thoughts turned to the battle fronts overseas. Then came post-war "normalcy," and the boom. Most people were relatively prosperous. They were restless. Millions of them now had cars the rapid extension of highways constantly widened the domestic-travel horizon.

Curtailed foreign travel also helped to swell the throng. During World War and for several years after, pleasure travel to Europe was light. Many Americans were for the first time persuaded to look to their own country for vacation-travel opportunities. And this impulse heightened by a vigorous domestic-travel propaganda: "See America First."

A rather definite measure of the post-war American rush to the open spaces may be had from national park attendance statistics. The present park system was consolidated on a Federal basis in 1916. At the outset, annual attendance ran approximately 350,000. By 1919, it was three-quarters of a million; by 1921, more than a million. In 1926, it was close to 2 million; by 1932, park attendance exceeded 3 million; and in 1939, nearly 7 million people visited the national parks. The figures do not, of course, include the visitors to national monuments, national historical parks, and other miscellaneous areas administered by the National Park Service.

Comparable figures show that in 22 years, attendance in national parks increased nearly 20 times while the acreage was not quite doubled. On the national forests it increased more than 10 times, or from 3 million to 32 million. Apparently the major factors in growth of use in both national parks and national forests were neither advertising nor provision of facilities—or the absence of either—but rather the enormous expansion of all forms of travel, based on increased national wealth and leisure and on autos and good roads.

This mushroom growth in attendance brought consequences and problems that had not been clearly foreseen. The terrific concentration of use in such restricted areas as the floor of the Yosemite, on Mount Rainier, and in upper Geyser Basin in Yellowstone caused serious overuse of camping areas, extension of roads in a not always successful attempt to spread use, and the development of grave mass-policing problems.

Foresters have been having the same trouble, but not, generally, as intensely. With a growth from some 4-1/2 million visits in 1924 to 14-1/2 million visits (exclusive of transients and sightseers) in 1938, parts of the forests have developed centers of very heavy use. Where there has been but a limited area of usable land near a great city, where only a single mountain lake is available to a large population, and in comparable cases, concentration problems have developed, differing only in degree from those on some of the national parks.

The tendency of crowds to attract crowds has not been offset entirely by attempts to divert them to new areas. The administration of the use has not been completely simple nor wholly successful.

Public use of national-forest campgrounds has reached such tremendous proportions in recent years as to create many new administrative problems. Supervision becomes each year more necessary, not only to prevent misuse, vandalism, and misconduct, but also to regulate the flow and distribution of the tide of campers.

Many people who discover the free camp sites incline to stake claim to them, in the traditional American manner. They tend to squat on or occupy campgrounds for unreasonably long periods. The Forest Service has had to establish time limits on occupancy of camp spots at crowded areas. But no set limits are enforced until pressure of demand requires it.

The fuel problem becomes each year more troubling. Fuel wood soon gets scarce around a much-used site. There are still forest areas where dead limbs and sticks to supply camping requirements may be picked up by the users. In others, the Forest Service follows the practice of dragging in fuel logs for campers. It is usually possible to do this with the campground maintenance crews, without great expense. Snags and sound down material are a nuisance and in places a fire hazard. Their removal for such use is a sound measure of forest sanitation.

QUESTIONS . . . But often it is hard to find the time or the help. And to drag in a fuel log for chopping and then put the forest visitors out of mind, so far as firewood goes, is not always practical. The ax is a tool with which citizens of our elder and more urban parts, particularly, have lost acquaintance. They make a fine, bold slash (the spirit of the woodsman still live in them) but naturally they are inept. It takes time to learn to chop wood right. City people are likely to hack up their shins, and the cut may be serious. This is especially true if the ax is chained to a tree with rather a short tether. No one can really chop wood with a tethered ax. Even amateurs soon learn to break the chain and some of them take the ax home with them, as a souvenir, perhaps. The fuel question in forest camps is really a problem.

Where, for various reasons, no cut wood is provided; where camp sites heavily used have led to a scarcity; or where free wood, freely cut and served, has led only to excessive use and thievery, vandalism increases. Only 1 guest of the forests in 10,000, perhaps, goes in for this sort of personal expression, but the total damage, the country over, mounts up. For something to burn in the fire, living trees on the site are hacked down, and tables and benches and parts of shelters are chopped into firewood and burned. This seems to happen most often on desert or semidesert camp sites. The policy here is to supervise camp sites more closely (with fixed forest guards, whenever that is possible), and to encourage the use of portable stoves that burn kerosene for camp cooking.

Difficulties of making sanitation keep pace with increasing use, on peak-load holidays especially, have been suggested. The problem is actual, and not to be dismissed with a snicker. On the heaviest used camps of New England, chemical toilets are generally preferred, not because they are any better than flush toilets, but because flush toilets so often literally get jammed up and overflow during the holiday overload. And at the close of such a day or days on the most heavily used sites, as has also been indicated, the job of cleaning up and incinerating the scattered garbage on many a camp or picnic set is rather like cleaning up a little slum.

Finally, there is the pure-water problem, and the question of opening more new swimming places. Should this be done? Chlorinated reservoirs are not as yet necessary at most forest camps, bacterial tests show, but there is a real prospect that at certain places both drinking and bathing water may soon have to be chlorinated in order to be safe.

This looks to the future. What of swimming places now? There are some 70,000 miles of fishing streams on the national forests, with countless swimming holes. There are countless lakes, bayous, and a considerable stretch of gulf or ocean shore. Consider the problem of bathing in inland waters only, for the moment; and consider particularly, the urge of the people to visit and plunge, in some number, into most of the new ponds, lakes, and reservoirs being created on the national forests and off of them, and as a part of a sweeping soil-, water-, and game-conservation program, the country over.

In dry-land country, where the reservoirs are not as a rule replenished with running water all year round, this urge to bathe and swim in clear, deep water seems instinctive, almost frantic; you cannot keep them out of it. And some of the new lakes and reservoirs into which they plunge so gladly, in desert New Mexico and Arizona for instance, have a foul, fungous smell to their stagnant waters in the dry season.

It is natural that eastern, humid forests should welcome swimmers, in general, and seek to provide dressing quarters and at least a part-time lifeguard furnished by the CCC. It is natural that the far western forests should contribute to any discussion of a general policy on this problem hearty wishes to keep the facilities as simple as possible.

|

| The great mass of them are fine, decent people, enormously grateful for any little thing that can be done for their safety and comfort. PINE CREST RESORT, STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST, CALIF. F-370786 |

For see what it involves, anywhere, East or West, the development and maintenance of some modern equivalent to the old swimming hole in a public forest: It is not just a matter of keeping the water sanitary. If you are going to concentrate bathing or swimming at some ordinarily safe place, rather than let people scatter and try it almost anywhere, you must provide some decent shelters where men and women may put on their own (or rented and sterilized) bathing suits; and where they can reassume civilized garb with a decent degree of supervised separation afterwards. Present appropriations do not allow for this at most of the many natural watering places on our national forests or for trained and watchful lifeguards to rescue people from drowning.

The easy way, on paper, is simply to close the new watering places to swimming. But to post signs does not really close these watering places, and it is a question whether safer places should be posted: Keep Out. The people, especially the wilder youngsters, don't keep out, and a certain number of them drown each year.

But this, and many other questions which affect the life, limb, and spirit of Americans seeking outings must be met. The need behind this increasing rush into the open is actual and urgent. It must be met, and governed, in some degree. The hard times which followed the lush times of the early 1920's did not notably reduce the pressure on outdoor recreational sites and facilities. In many places, where such recreation was cheap or was free, the load increased. Distressed farmers and tradesmen from the middle country and High Plains bought more gas from many a filling station on the main routes to the Rockies and the Coast in the lean early thirties than ever before.

The plain truth is that forest recreational facilities have been extended under the push of a constant, driving, increasing demand. This has been done mainly by the willing aid of relief labor. Much has been done but it falls far short of meeting the peak loads and the immediate prospect of an increasing human use. The recreational plant or equipment is overextended in point of existing appropriations and in point of the time required of the existing personnel for this one aspect of modern forest management, but it falls far short of satisfying rapidly growing demand.

Most of the existing campground developments on the national forests have been made during the 5 years since the CCC and other emergency projects began in 1933. Here is a short list of the principal installations to date:

| Stoves, grates, cooking and heating fireplaces, and barbecue pits | 21,196 |

| Campground toilets of all types | 7,673 |

| Garbage cans, pits, and trash incinerators | 11,255 |

| Campground tables and benches | 31,603 |

| Springs, wells, reservoirs, and pipe-line systems | 2,859 |

| Amphitheatres (seating capacity 11,565) | 46 |

| Campfire circles | 1,783 |

| Buildings and shelters of all kinds | 1,093 |

| Automobile parking areas, car capacity | 48,553 |

At present the total number of developed camp and picnic grounds, large and small, in all of the national forests is 3,819. These will accommodate 240,000 persons at one time, but they do not carry present seasonal loads, which in the 1938 season amounted to just under 11,000,000 visits. On Sundays and holidays, many campgrounds are hopelessly overcrowded.

Development of additional campgrounds and the installation of necessary facilities are urgently needed to keep pace with the annual increase in use. If campground use should double or perhaps treble within the next 10 years, as now seems probable, either large numbers of campers will have to be turned away, inadequately served, or the campground-improvement program must be expanded.

The original charge of the Forest Service was simple and strictly practical. New needs have arisen to press hard and broaden the concept of what national forests can and must yield, from the standpoint of "the greatest good for the greatest number in the long run," on a hard-boiled and thrifty basis—multiple use.

Our national forests still report to the people largely in terms of cash income. They are producing units. These increasing recreational tides do bring in some revenue from charges for special services, but it is the barest dribble to the forests' funds, direct. Tourists and campers bring money, and money badly needed in the main, into a multitude of communities roundabout; but little or nothing that a forest officer can enter on the credit side of his accounts. Recreation falls mainly on the cost side in forest keeping, and the entire amount available for recreational use on the whole White Mountain Forest in 1938, for instance, was $25,530.

IT IS by no means the general disposition of professional foresters to hold out their hats for more money to be used for a more elaborate extension of public recreational structures and facilities. Most of them would rather see things kept plain. Foresters in general do not yearn to go any deeper into this socialized recreational business; but the push is on, strongly, plainly, not so much in lobbies, or in the organs of public opinion, or in Congress and the State legislatures, as in an actual pressing swarm of the people, themselves.

It is only in part a question of planning and preparing for forest guests who are coming; it is more immediately a struggle to care for the throng of guests at hand. To regard wrecked cover distastefully, to push wearily out night after night hunting lost campers, to observe the nuisances that occasional parties (even of college youngsters) commit on Government property and equipment, and to think savage things about "the dear public" as foresters occasionally do, solves nothing. These are the people's forests. They need and have the right to use them for their pleasure. Foresters make them welcome, and are really glad to have them come.

And not one forest guest in a thousand abuses the privilege wantonly. The great mass of them are fine, decent people, enormously grateful for any little thing that can be done for their safety and comfort. Most of them, as a later chapter will show, fall within the lower income brackets. The public forests offer the only chance for many of them to get some change and rest. And it is conceivable that the restoration of health and spirit which forest outings visibly produce will be worth as much to the Nation in the end as all the material national-forest crops.

Present facilities are in most places crucially inadequate; and by the most conservative of forecasts, based on attendance charts, projected recreational use of the national forests seems certain to double, at least, within the next 10 years.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap6.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |