|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part Two

KINDS OF OUTINGS

Chapter Five

The Wild

The wind blew up from the river, fresh and mysterious, against my face. The air was alive with the faint odor of juniper. Far, far away, beyond the river, beyond the canyons, beyond countless miles of mesa, so far away that they were sometimes mountains of earth and sometimes mountains of an ancient, dried-out moon, rose a snow-covered divide that seemed to bound the universe. Between me and this dimmest outpost of the senses was not the faintest trace of the disturbances of man; nothing, in fact, except nature, immensity, and peace.

Robert Marshall, Nature Magazine, April 1937.

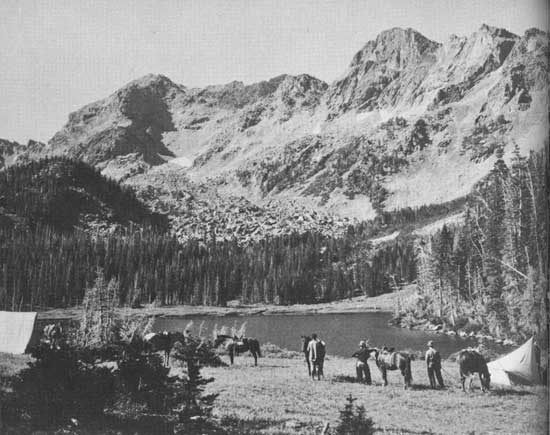

WILDERNESS TRIPS provide under conditions of some hardship a return at once serene and bracing to America's far past. These explorations of the primitive vary widely in respect to the rigors imposed. Dude ranchers frequently trek their customers out through wilderness areas nowadays, with cowboy guides to keep watch upon them with a sort of rough tenderness and bed them down on inflated, rubber mattresses at night.

But often dude ranch trips, where the dudes are hardier, are very much tougher than that. The job, indeed, is sometimes to hold down robust businessmen who want to push over mountains and engage mountain lions barehanded—to keep them from needless dangers and accidents.

|

| Dude ranchers frequently trek their customers out through wilderness areas. SPANISH PEAKS WILD AREA, GALLATIN NATIONAL FOREST, MONT. F-331232 |

In the summer of 1938 with three companions the late Robert Marshall, of the United States Forest Service, attempted to climb Mount Doonerak in Alaska, something no one had ever tried. Much the same unusual weather that stirred up the New England hurricane was breeding there in the far Northwest late that August. Rain and flood beat at the party for days and weeks on end. Mount Doonerak is yet to be climbed. Cast under ice in the floodwater wreck of a 30-foot open boat, returning, these wilderness adventurers were miraculously lucky to escape with their lives. They salvaged some provisions from the wreckage, made packs, and walked in a hundred miles or so, over the roughest sort of country, in 3 days. On their 29-day outing they encountered 27 days of rain. Yet all of them swore they would not have traded those 29 days for a year of humdrum life back home. Besought by more sheltered spirits to explain the charm of it all, Marshall issued a personal memorandum, in part as follows:

"Of course, all this is completely useless. No human being except myself and my partners will be happier nor will the world be a bit better off because of our exploration and mountaineering. There seems, however, no reason why we should not be as much entitled to the fun of this exploration as anyone else. And it is relatively inexpensive. The entire expedition cost less than the cheapest new car, than a vacation trip to Europe. Consequently, if the adventure was useless, it was also relatively harmless; but from an emotional standpoint it was the top of the universe!"

The wilderness is vanishing but it has as yet to vanish completely from the face of this continent, and there is an increasing insistence that the remaining wilderness be not blindly entered and subjugated to the pursuits of civilization, but kept as it is.

When it comes to determining the precise degree in which such areas should be held inviolate, sentiment varies. In a region where the pioneer urge to open up new country still burns high, one recent correspondent argued for a "gradual and measured introduction of roads and resort facilities" into a number of wilderness areas there. And to this a responding wilderness enthusiast replied at once in a ringing letter beginning: "There can be no such thing as a gradual and measured ravishment!"

The extent to which emotions essentially patriotic and in a sense religious must enter into decision of wilderness use or disuse may be gaged in some part by reading the "platform" of The Wilderness Society, organized at Washington, D. C., early in 1935.

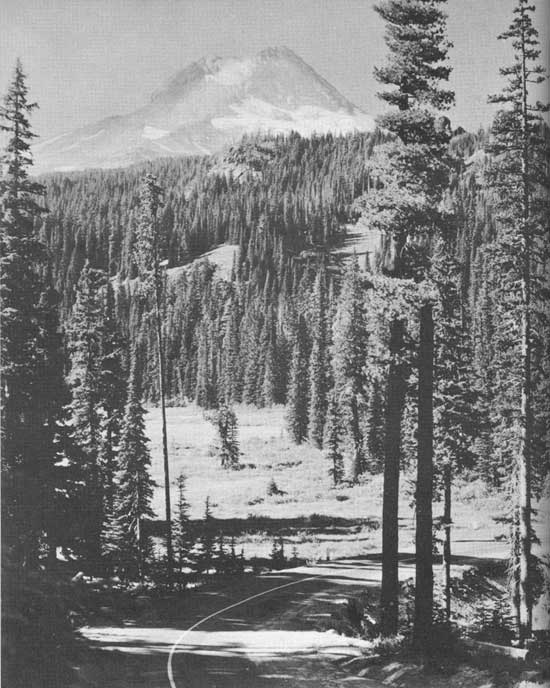

"PRIMITIVE AMERICA is vanishing with appalling rapidity. Scarcely a month passes in which some highway does not invade an area which since the beginning of time had known only natural modes of travel; or some last remaining virgin timber tract is not shattered by the construction of some irrigation project into an expanding and contracting mud flat; or some quiet glade hitherto disturbed only by birds and insects and wind in the trees, does not bark out the merits of a patented nostrum or the mushiness of 'Cocktails for Two.' Such invasions are progressing everywhere so rapidly that unless fought as ardently as they are pressed there will soon be nothing left of those wilderness characteristics which make undisturbed nature the most glorious experience in the world to many people.

"We recognize frankly that the majority of Americans do not as yet care for these values of undisturbed nature as much as for mechanically disturbed nature. We are willing that they should have opened to them the bulk of the 1,800,000,000 acres of outdoor America, including most of the superlative scenic features in the country which have already been made accessible to motorists.

"All we desire to save from invasion is that extremely minor fraction of outdoor America which yet remains free from mechanical sights and sounds and smells. We do hold that those few areas which have thus far escaped man-made influences must be preserved in their natural condition, unless it can be clearly demonstrated that some other use is of compelling value."

Exclusionists among wilderness lovers would bar "motor roads, radios except for fire protection, railroads, cog roads, funiculars, cableways, etc." They would severely limit "graded trails, ski trails, footbridges, cabins and shelters, sheep and cattle grazing, fences." "Power lines, water-power developments, irrigation projects, and logging operations" they would prohibit entirely. "Airplanes, motorboats, telephones, lookout and ranger cabins should be permitted only when they are necessary for fire protection or emergency."

As to erosion and insect control, erosion control "should be permitted in areas where it is necessary to undo the effects of faulty land use"; and insect control "should be permitted only when it is necessary to save the wilderness forests from destruction. Endemic insect attacks occurring in the wilderness should not be disturbed."

But even in this it is evident that some concessions to modern civilization are contemplated. If wilderness areas bordering civilization are given over entirely to a laissez-faire policy of inaction, with no human interventions planning, or management whatsoever, then fire, insect infestation, or excesses of erosion initiated perhaps by unnatural processes outside the area may destroy them. The paradox is plain.

|

| Primitive America is vanishing with appalling rapidity. MOUNT HOOD NATIONAL FOREST, OREG. F-354935 |

A section of the National Resources Board 1934 report on recreational land use, prepared by the National Park Service, presents with a calculated breadth and simplicity the present dilemma on the remaining primeval spots and the larger expanse of wilderness amid our State and national patchwork of private land, parks, and forest today. Briefly to quote:

"Under the increasing pressure of motor travel, control of road building becomes an important factor in the preservation of primeval areas. However, only one motorist in hundreds ventures a mile from his car; the rest are amply content with the road and the museums, lectures, and pleasures of developed centers. For the few, the trail and the primeval; for the many, the points of concentration and comfort.

"By sacrifices of small areas sufficient to house, interest, and entertain the masses, vast areas are preserved to the student for today and for generations to come. However elaborate our road system to the parks and between them may become, the roads within need be only few. Thus is met the problem of preserving our national parks while we also use and enjoy them . . .

"Man's success is largely determined by his knowledge and ability to make use of natural laws. The best places for scientists to learn first hand of nature's laws are found where nature's laws still operate undisturbed by man . . . We can afford to be careless with those things which are easily replaced, but those which can never be replaced must have special protection and care . . . Fairness to those who have similar rights to ours, but who will live 100 years from now, demands that we save intact some of primeval America . . .

"Though in general a hands-off policy will best care for a primeval area, a management policy to retain the primeval is necessary. It is still a question as to how far we may safely go in providing artificial protection against fire.1 Fire control nearly always demands additional trails, telephone lines, and lookout towers. The provision of this equipment furnishes a means of fire protection but at the same time brings in man-made control as against natural control."

1On a number of scattered wilderness and more developed forest stretches, ranging from Florida to the Cascades, more fires are set by lightning than from any man-made cause. Over the country as a whole, however, man causes more forest fires than lightning.

ZONES OF WILDERNESS . . . It was about 15 years ago that the first national forest wilderness area was set aside. Today, of 70 of the Nation's established or proposed wilderness areas of 100,000 acres or more, 52 are on the national forests. And 11 out of 13 of those containing 500,000 acres or more are entirely or chiefly on national-forest land. Natural conditions here in many places reasonably compare with general conditions at the time of the Louisiana Purchase.

Today, too, the Forest Service recognizes some 19 different types of areas where recreation has dominant or exclusive importance. The first five and the eighth of these classifications as listed here stress, in varying degree, the preservation of wilderness values:

A "wilderness area" must be designated by the Secretary of Agriculture, and must remain content with primitive transportation and habitation. It is defended against roads, resorts, organization camps, summer homes, and commercial logging. It may not be modified or eliminated except by order of the Secretary, and then only after public notice and a 90-day period within which public hearings shall be held if there is a demand for them. The smallest area recognized as a forest wilderness is 100,000 acres, and its boundaries must be at least one-half mile back from any road.

A "wild area" is a small wilderness area of less than 100,000 acres, but of at least 5,000 acres.

A "virgin area" is 5,000 acres or more on which there has been virtually no disturbance of the natural vegetation. A "natural area" is set aside to preserve special botanical values, but is not large enough to qualify as a virgin area. A "geological area" is set aside to preserve features of the formation and structure of special interest to students. An "archeological area" is set aside to preserve material evidence of aboriginal American peoples, and an "historical area" preserves interesting evidences of the life and activities of people who have lived since the advent of the whites on this continent.

A "scenic area" is a spot of extraordinary beauty, requiring special preservation. All of such spots are relatively small. Forest wildernesses are much larger.

Because of the necessity of fire control, forest wilderness areas and the smaller wild areas are equipped with lookout towers and telephone lines. With the development of radio, telephone systems are becoming less important. Simple trails are permitted, not differing greatly from the Indian trails that were the highways of the forest before the white man came. These are built primarily for fire protection. They also help to bring safely into the wilderness some who would not otherwise venture that far back.

Here and there sizable areas will in the future be set aside as trailless wildernesses where those who dare may enjoy the adventure of finding their own way.

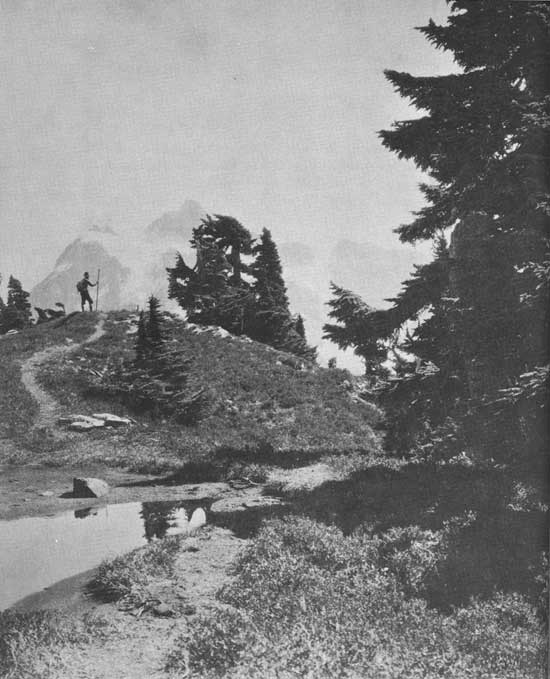

OFF THE TRAIL you are on your own. Goodbye to the endless repetition which machinery imposes; goodbye to a life where the same events are certain to be repeated, to the world where you know exactly what lies down the street or around the corner.

Here is a new world, clean and shining; a new life! Mustering all your knowledge of woodsmanship, you may be seeking blazes along the dim trail which winds among the ancient hemlocks and cedars on the slopes of the Selway Mountains; you may be searching the alpine meadows of the lofty Absarokas for the old, crumbling cairn which marks the only route of descent through the encircling rimrock; you may be trying to guess whether the channel you are following through the dense fir of Lac La Croix is leading toward your destination or merely to the foot of some dead-end bay; or you may be climbing some trailless ridge among the Maroon Bells of Colorado and conjecturing on what world lies beyond the Continental Divide. Such experiences are dominated by a jaunty feeling of uncertainty.

The experienced wilderness traveler faces uncertainty calmly, with confidence and an exultant spirit. He walks alertly, the master of his destiny. Skillfully he packs his food and bedding on a horse or carries it on his own strong back. He carries some food, but eats the better by whipping mountain waters rich in fish. He can ride or walk 40 miles a day with ease and elation in his hardihood. He is at home in the wild.

|

| Your are on your own. MOUNT BAKER NATIONAL FOREST, WASH. F-191212 |

There are certain natures and characters that, however highly developed and admirable, simply do not rise to the exacting requirements of wilderness conditions. Partly it is the altitude; high elevations exert a depressing effect on some people. But it is also the endless expanse and grandeur of the scene. That is often too much for them; it makes them feel like ants crawling, tiny, insignificant; it depresses a fellow, they say. On a long trip such people often wearily count the hours and miles. When at length they come down the last divide, back into civilization, and behold neatly clad sportsmen following little white balls around a beautifully tended golf course, they all but weep for joy.

There are other people, unused at first to the wilderness, who react favorably to it; who since their first trip have reentered it, more on their own. It is simply a question of one man's meat; no ethical or moral judgments enter, and this should be made plain. There are others, even among foresters, who can make their way to fishing streams and glades no farther from a highway than to dim the purr of tires and the sound of voices, and feel or imagine with greater comfort that they are at least a million miles from everything.

It is really important, for reasons both of public safety and of effective forest administration, that nothing said here by wilderness lovers be taken as a dare to urge more forest visitors beyond the trails, beyond their capacities or tasks as woodsmen and explorers.

"Take it easy. Test yourself," those experienced in the wilderness advise. See how much of utter isolation you really like, want, and can take. The old-time frontiersman, you must remember, took all the time he was growing up to fit himself for long hikes beyond the trails. And even then, many brave men and women found in untrod lonely spots no necessary satisfaction, and stuck close to the trails.

It is, to speak quite seriously, no fun to be lost in the woods. Some people who go through the experience and come out of it are never quite the same afterwards, and even with the entire personnel of the forest out day and night on search parties, the unprepared wilderness adventurer is not always found alive. This is especially true of mountain climbers, and of skiers or other winter sportsmen, often youngsters, who strike off and attempt slopes beyond their powers.

For those who are fit, the still new world lies open and offers escape. The man who fishes one of the remote lakelets of the high Uintas may not catch any bigger trout or any better fighters than the one who fishes a heavily stocked river from the highway bridge, but he catches them in an unaltered setting and this adds to his joy. The man who packs into the heart of the Gila Wilderness for his hunting may not shoot any bigger deer than the man who knocks them down from near the highway, but he pursues the game in a world where he can still feel like a Kit Carson or a Daniel Boone. The man who climbs the trail up Agness Creek to the crest of the Cascade Mountains may not see any more jagged peaks than along the Stevens Pass Highway, but the environment from which he sees them exhibits no sign of civilization save the dead ashes of a few old campfires and the simple trail which has changed but little since it was tramped out centuries before by the feet of Indians.

Time is of no consequence in an environment that has been developing through an unbroken chain of natural sequences for millions of years. A man or woman camping among the remote peaks of the High Sierras or on the source streams of the Flathead River finds no jarring sight or sound, no discordant clash with instinctive feeling of oneness with eternal and natural values. Nor does he in that vast Quetico-Superior country that lies astride the Minnesota-Ontario international boundary. This latter country has been described as embracing the most usable, beautiful, and primitive canoe waters left in the United States, with an endless variety of woods, rocky shores, mountains, and lakes. It is less than 24 hours' travel from Chicago, less than 12 hours' from Minneapolis. But except for the airplane—sole rival of the canoe—lakes and rivers provide the main avenues of travel within the bulk of its millions of acres.

The Quetico-Superior area includes thousands of crystal-clear lakes and hundreds of miles of forest-fringed streams up which canoes of French coureurs du bois once knifed their westward way. Here the canoeist-camper, who has outfitted at a trading post on the fringe of the wilderness, may cruise for weeks through labyrinthian waterways without retracing his course. Waterfalls will fascinate him. Native game will watch him as he glides along. Cut off from civilization, he pitches his tent where night overtakes him . . . cuts his own wood . . . catches fish . . . cooks his own meals . . . becomes one with nature.

Some 900,000 of these acres within the Superior National Forest have been formally dedicated by the Forest Service as a primitive or roadless area. And following years of hard work by the Quetico-Superior Council, the Quetico-Superior Committee, appointed by the President in 1934, has recommended creation here of an international wilderness sanctuary and peace memorial to the Canadians and Americans who fought side by side in the World War.

To close this chapter with a more definite and personal description of what men seek beyond the farthest established campsite, the late Robert Marshall, quoted at the opening of this chapter, wrote the following account of one of his recent forest wilderness trips:

UP FROM WIND RIVER. The horses were waiting at Dickenson Park. Here the dirt road ended. Here the wilderness began. Beyond were the Wind River Mountains without a single road in an expanse more than 100 miles long and averaging 20 miles wide. It was a primitive land where all travel was by substantially pioneer methods which were used before white men had ever invaded this Shoshone country in Wyoming.

We saddled and started climbing through lodgepole pine which made us duck constantly to avoid being scalped by overhanging branches. Toward the top of the mountain the pine gave way to spruce and fir, and a little later we were out on the open divide. To the west lay the promised land with wild, mysterious summits stretching as far as the eye could reach along the backbone of the Wind River Range.

Directly below was a basin with 10 fresh-looking lakes surrounded by dark green timber and backed by rocky peaks. Look as closely as we could, there was not the slightest evidence of man's activity. We started down the west slope toward this wilderness basin. At many places the mountain was so steep we had to lead our horses. One time we got rimrocked and had to climb back several hundred feet. That was where Cap took his big tumble when a ledge split off, but although he was 60 years old, it left him with no more serious injury than a badly barked shin.

Finally we reached the valley floor. It took only a short time to pitch camp in a bright meadow, and since the afternoon was still early, we set out on varying occupations. A couple of fellows sat around the meadow, loafing and enjoying the sunlight. Four enthusiastic fishermen started to whip nearby waters which had not been fished for a year.

Meanwhile, I started climbing afoot to the uppermost lake in the basin. When finally, after skirting two lower lakelets and following a series of great cascades, I reached this remote water, it seemed as if I were far beyond the zone of human penetration. There were no faintest sounds, no dimmest sights, to give even a hint of civilization just rocky shores and a scattering of wind-swept trees, and in the background, the pinnacle of Mount Chauvenet.

We broke camp early next morning and after cutting across country a short distance, came to a good trail leading southwest. Since we were the first party of the year to go over the trail, we had to stop frequently to saw out windfalls. The scenery was unexciting but lovely, with lodgepole pine and spruce and green grass and many showy flowers of early summer. Our trail, which had started on a level, began to get steeper. After awhile we abandoned it and headed our horses up an open slope until finally we reached the top of a nameless summit. Below us were several snow-fed lakes, clear and blue and deep. Back of them were the steel-gray summits of the Continental Divide which cut a sharp line of cleavage against the bright-blue sky. Northward a spectacular peak seemed to be on the verge of tumbling over to the east. The ranger said that it was Lizard Head and that it was so rugged that no one had ever succeeded in climbing it.

We ate our lunch, and then dropped back to the trail which we followed northward toward the headwaters of Popo Agie Creek. After 10 miles we reached a large meadow just below the overhanging Lizard Head where we established camp for the night. At the head of the meadow lay the Continental Divide—a granite range composed of what seemed unscalable peaks.

Next morning we started up the trailless green slopes from which Lizard Head rises like a gigantic pillar. We speculated on possible routes of ascent, but none of us was eager to try them. Halfway to the pass were two deep lakes entirely surrounded by rock slides. One could hear the continual roar of water splashing toward them from snowbanks melting rapidly under the hot July sun. When we looked around we saw, back of us, the jagged skyline of the Continental Divide.

The climb was steep but not difficult. We had hardly started the descent, however, when we were in trouble. The ground where the snow had but recently melted was like quicksand and three of the horses went down in rapid succession. It was nip and tuck as to whether we would save one of them, but a couple of our most skillful wranglers calmed him as he lay kicking frantically, and removed the pack.

Grave Lake is the most remote of the larger Wind River lakes. We followed a dim trail far back under the Continental Divide in order to reach its shores, from which we looked through a frame of white-bark pine into a crazy conglomeration of precipices jutting up at almost every conceivable angle. Wooded points extended into the lake and divided it into enchanting bays, while overhanging everything was the feeling of mystery which pervades the country at timber line. A sudden thunderstorm, driven across the lake by a furious wind, added to the feeling of being at the ends of the world. By the time we had followed the winding trail 5 miles to Washakie Lake, directly under symmetrical Washakie Peak, the storm had passed. A peculiar narrow peninsula extends nearly across the lake, dividing it into a main body of water 2 miles long, and an infinitely placid lagoon. On the latter we camped and watched the setting sun change the cloud-flecked sky into such a flaming crimson that it almost seemed alive.

The climb next morning to the Continental Divide was across snow banks for half the way, even though it was mid-July. At Washakie Pass we stopped a moment to breathe, simultaneously, Atlantic and Pacific air. Then we descended on the west side to a creek with the morbid name of Skull, where we had our lunch. Thereafter we left the trail and rode our horses over a couple of mountains in order to obtain a better view of the surrounding topography and vegetation.

The camp that night was at a romantic location. In 1902, when the sheep were just beginning to penetrate this section of the West, the cattlemen who had been using that range for years took the law in their own hands. They captured a couple of sheep owners and tied them to trees. Then they drove their 2,000 sheep into a corral and slaughtered them before the frantic sheep owners' eyes. About the time the owners expected to share the fate of their flocks, they were untied, given swift kicks, and told to leave the country and never return. The old sheep bones from the massacre of a third of a century before still lay in the corral.

Next day we rode along just west of the Continental Divide for 25 miles. It was up one pass and down the other side, and up and down, and up and down again. We passed a myriad of small lakes sparkling in the intense sunlight of this high plateau land, 10,000 feet above the sea.

At the third pass of the day some of us left our horses and proceeded to climb Mount Baldy, from where we looked across to the highest summit in the Wind River Range. Directly in front of us were a half dozen peaks towering above 13,000 feet Gannet, Fremont, Warren, Knife, Sacagawea, and Helen. They were so massive and substantial it almost seemed as if they constituted the boundaries of the earth.

We sat quietly, enjoying the view for more than an hour, until the chill which came with lengthening shadows reminded us what a poor place this would be to spend the night. We dropped down to a meadow where the remainder of our party had already established camp and had quickly caught their limit of trout from a nearby lake which no white man ever before had fished.

Next morning dawned sorrowfully enough as the last day of the expedition. I left the other members of the party and set out to walk as far north as I could that day and still return by dark to the end of civilization. Again, it was a case of up one pass and down on the other side, all day long over 36 of the most splendid miles a human being could know. There were continual alpine lakes among the rocks and meadows, continual stunted pine and spruce and fir. On every side were limitless climbing possibilities, including opportunities for that greatest of all mountaineering thrills, a first ascent.

It was peculiarly elating to stride along through the world above the 10,000-foot contour where an energy unknown at ordinary elevations seemed to be liberated. One felt like keeping on and on forever. However, I had set Green River Pass as the limit of what I could do and still reach road's end before dark. As I looked northward from the pass, it was pleasant to realize that the closest road across the range, after 2 days of steady travel northward, was yet 50 miles away.

I turned reluctantly and started back. It was just sunset when I reached the road above Fremont Lake, the outpost of civilization, the end of the primitive. It tied me into the world of modern life with all the cumulative marvels built by man's ingenuity from the dawn of time. Yet, as I took one last look into the Wind River Mountains where we had been buried for 6 glorious days, I had the feeling that all of man's ingenuity could not create anything to equal the world of the untamed wilderness.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap5.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |