|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part Four

WHAT REMAINS?

Too long we have reckoned our resources in terms of illusion. Money, even gold, is but a metrical device. It is not the substance of wealth. Our capital is the accumulation of material and energy with which we can work. Soil, water, minerals, vegetation, and animal life—these are the basis of our existence and the measure of our future.

Paul B. Sears, This Is Our World, 1937.

Chapter Fourteen

New Land: Alaska

Were the attractions of this north coast but half known, thousands of lovers of nature's beauties would come hither every year. Without leaving the steamer from Victoria, one is moving silently and almost without wave motion through the finest and freshest landscape poetry on the face of the globe. . . . It is as if a hundred Lake Tahoes were united end to end. . . . While we sail on and on thoughts loosen and sink off and out of sight, and one is free from oneself and made captive to fresh wildness and beauty.

John Muir, First Journey to Alaska, 1879.

THE PRICELESS PRIMITIVE quality of Alaska and the distinctiveness of its national forests are Territorial assets of enormous value. Here is a country almost continental in size, with richness and variety of inspirational resources, a frontier as yet little changed by man. Its land still lacks settlers. Its mineral deposits have been only partially developed. Its great river systems, mountains, volcanoes, tidewater glaciers, and fIords retain their primitive grandeur. The great conifer forests that clothe the south coast stand intact. The vast, open woodlands of the Yukon drainage and the far-northern tundra areas remain in large part unbroken wilderness. Wildlife is abundant, including the caribou which roams the interior watersheds in great herds as the bison once roamed the Great Plains. The population, white, Indian, and Eskimo, barely exceeds 1 person to 10 square miles.1 Alaska is still almost entirely public domain with only 1 percent of its area in private ownership.

1The area of Alaska is 586,400 square miles. The population in 1939 is estimated to be 62,700.

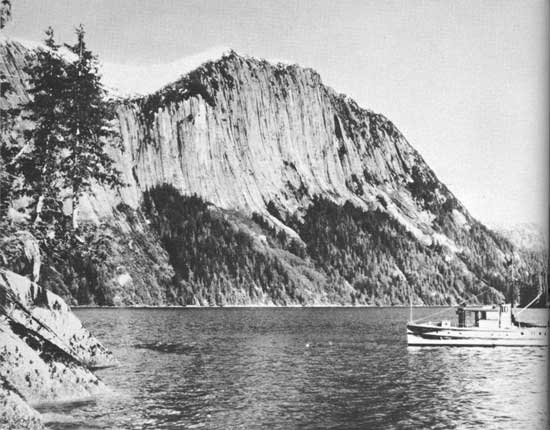

The national forests of Alaska comprise a narrow strip of mainland, with hundreds of adjacent islands. They extend from the south boundary of the territory to the town of Seward. By localities the forests cover most of southeastern Alaska, the Prince William Sound region, and the eastern part of the Kenai Peninsula. The length of this maritime strip is 800 miles, but there are so many islands and deeply indented coasts that the shore line is more than 12,000 miles in extent. The two national forests, the Tongass and Chugach, cover nearly 21 million acres, about 5-1/2 percent of the total area of the territory. Both mainland and islands have extremely rugged topography. High mountains rise abruptly from the water's edge. An intricate network of narrow channels, including many extending far inland, brings all parts of the region within easy reach of tidewater.

|

| Often the narrow channels are bordered by towering mountains of bare rock, worn smooth by glaciation. PUNCHBOWL COVE AREA OF RUDYERD BAY, BEHM CANAL, TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST, ALASKA. F-368244 |

Human occupancy is confined largely to scattered seaport towns. Except for these towns and isolated canneries, the shore line remains primitive. So does the back country except for mining operations here and there. Rough topography makes extensive highway construction prohibitive; most roads radiate no more than a few miles from the towns. Less than 1 percent of the total area is suitable for agricultural use.

This southeastern region is nearer the United States than any other part of Alaska. It is crossed by the main steamer route and is only 2 days by boat from Seattle. The highly developed salmon-packing industry and mining activities have made it the most populous part of the Territory. There are approximately 24,000 residents, white and native. These factors, combined with its recreational appeal, bring to the national forests more visitors, both tourists and residents, than to any other part of Alaska.

The Tongass National Forest is a land of waterways, a highly interesting region geographically. It presents the picture of a high, rugged mountain range that subsided countless centuries ago, partly below the sea; its labyrinth of protected waterways were one time valleys of rivers and creeks, and its islands are the tops of formerly connected mountain ranges. The famous fiords of Norway, with all their grandeur, hold nothing more inspiring than those seen in Alaska. Often the narrow channels are bordered by towering mountains of bare rock, worn smooth by glaciation, so nearly vertical that the boat cannot land except in a few places.

Going up Tracy Arm, a narrow waterway 20-odd miles long and often not more than one-fourth of a mile wide, a boat passes icebergs glistening in the sun. Generally the tops of the bergs are white snow-ice worn by wave action into caverns and overhanging shelves. The lower ice is usually a deep, steely, cold blue.

The boat heads, time after time, straight for a rocky cliff, and apparently into a cul de sac. Suddenly a narrow way opens up, almost at a right angle. The boat turns and goes on. Weaving and dodging icebergs, it comes without warning to the head of the Arm and there two immense glaciers rise 250 feet sheer from the water. The boat slows to a crawl through broken ice, bumping its way through small chunks. Avoiding large bergs, it approaches a mighty ice cliff. The engine is killed. The boat drifts. Suddenly the glacier cracks like a pistol shot. Then with a rumbling sound a hugh piece breaks off and falls into the bay, leaving a streaming trail of powdery ice, and slowly sinks. A wave breaks, widens, and rocks the boat. The berg rises slowly from the water, turns, revolves, finally comes to rest and floats slowly with tide and current. Wheeling above the water, along the cavern-filled face of the glacier, is a flock of gulls. A streak appears on the still, intensely blue water. It is a hair seal swimming with his nose out of water.

On the return trip one may pass an old Indian and his woman paddling a dugout canoe, or on a rock point a lone Indian with a rifle—watching. They are seal hunters. Here in the cleft of a cliff an Indian gathers his kill—six hair seals. He skins them and lowers hides and bodies with a rope to his canoe. A bounty of $3 is paid for each seal killed and the salmon area made safer from destruction. Clothing and moccasins will be made from the seal hides. The blubber will be dried and stored in gasoline cans against the cold of winter. He clambers down, carefully loads his skiff, and, disdaining to wave at the visitors, rows away.

Above the forest-rimmed sea lanes are great glaciers. They move slowly down the valleys of high coastal mountains and drain off ice from the extensive icefields of their origin. Many glaciers terminate on the ocean border, with towering fronts from 200 to 300 feet in height and miles in width. These fronts are daily pushed forward by gravity, only to be undermined by waves, broken down into avalanches of glittering ice that falls with a thunderous roar and throws spray hundreds of feet high. To geologists, or to any student of earth's history, these glaciers and the surrounding lands are doubly fascinating, for they present, in a limited space, a series of related geologic views leading back from present-day conditions to the time of the last Ice Age. Nowhere on this continent can glaciers be more readily visited than on the Alaskan Coast. They can be seen from an ocean or river steamer, from plane or motorcar, or from foot trails.

Innumerable lakes, carved out of the high gulches of steep mountain ranges by former glaciers, are sources of vertical waterfalls that also may be seen along the sea channels. Varied rock formations, extensive zones of mineralization, volcanic cones, lava flows, and glacier-carved land forms, all free of vegetation at high elevations, give a further variety to the scene. The minerals include gold, copper, silver, lead, nickel, and platinum. Marble and limestone are abundant and here and there, coal.

The native Indians, with their curious totem poles and customs, interest the casual visitor and the student alike. They form the Haida and Thlinget divisions of their race. Apparently they are more closely related to Oriental peoples than to American Indians. They occupy the immediate coast line and live in 15 or more villages of 100 to 500 population. Their living comes principally from the sea. A few community houses where they formerly lived still stand. Their outstanding art is the carving of totem poles which are placed within and in front of their dwellings to exhibit tribal emblems and perpetuate tribal legends. These Indians also make beautiful dugout war canoes that carry as many as 50 men. They are skilled in blanket and basket weaving, in silver engraving, and in the making of highly ornamental skin clothing. The Forest Service is restoring ancient totem poles and community houses and compiling family histories. Out from Ketchikan an entire Indian village will be rebuilt. Indians will do the work. They are free agents, not wards of the United States, and most of them make their own living.

The high latitude of this region, its lofty mountains, and the modifying effect of the Japan current on the temperature of lands near sea level give great variety to the vegetation. Within a range of several miles and 3,000 or 4,000 feet in elevation, the plants display many types. Many plants at the shore line are common in the States. Higher, the plant robe is that of Arctic lands. Lands uncovered by retreating glaciers show the interesting plant succession employed by nature to reclaim gradually bare land with an ultimate cover of hemlock and spruce. Retreating glaciers expose unpetrified wood and plants of interglacial forests which grew thousands of years ago. Wild flowers grow everywhere in profusion; the green and white background of forests and snow provides an ideal setting for the vivid flashes of color.

FISH AND GAME . . . Good trout fishing may be found in the many lakes and creeks, and the large king or Chinook salmon abounds in sea channels. To take them with light tackle is real sport. Recently the use of commercial airplanes, mounted on pontoons, has resulted in fishermen's raids on certain fresh-water lakes and brought likelihood of depletion. This needs to be regulated. Such conservation measures as are now applied by the Federal Bureau of Fisheries to assure perpetuation of salt-water fish should be applied here.

Alaska is outstanding in the world for its wilderness animals. Game is food to the Alaskan and fur bearers add to his cash income. But the greatest value of wildlife to the Territory and to the people of the United States lies in its attraction for public enjoyment. The principal big-game animals on the national forests are deer, mountain goats, black, grizzly, and Alaska brown bears, moose, and mountain sheep.

Among local hunters the deer of southeastern Alaska are the game most sought, but the sport attracts few nonresidents, possibly because of the widespread range of deer in the continental United States. The legal take is unimportant in view of a small human population and a great number of animals. Killing by isolated residents, the predatory wolf, and starvation during winters of exceptionally heavy snowfall are the principal decimating factors. Recent checks indicate a decrease in the number of deer. More intensive protection is called for, and is being applied.

Mountain goats are abundant but seldom hunted. Their habitat among the rugged mainland peaks affords ample protection. The black bear is everywhere abundant. He is little appreciated as a game animal in this region and has apparently multiplied greatly in the last 10 years. In the national-forest region the grizzly is found only on the mainland areas and more especially at the heads of long fiords and isolated bays. Perpetuation of this species in large numbers is an important feature of Alaska game administration.

The Alaska brown bear is the largest of the bear family and also the largest land carnivore on earth. Regarded as one of the outstanding big game animals of the world, it attracts the same class of sportsmen who hunt lions in Africa and tigers in India with camera and gun. A recreational resource of romantic appeal as well as local economic value, this game animal appears to be in Alaska. Its range covers at least one-fifth of the Territory but on the national forests the Alaska brown bear is confined to three large islands in southeastern Alaska, two islands in Prince William Sound, to the Kenai Peninsula, and to the outlying Afognak Island. As the national-forest land is the most accessible of the entire range, adequate safeguards for the animal are considered doubly important there.

Moose and mountain sheep are found over a large portion of Alaska but on the national forests they occur only in large numbers on the Kenai Peninsula. The Alaska species of these animals are especially prized by big-game enthusiasts and consequently are subject to careful administration. Like the Alaska brown and grizzly bears, both these species are true wilderness animals and their perpetuation requires protective measures against too great a contact with civilization.

PLEASURE GROUNDS . . . The same need exists in Alaska as in the continental United States for community outdoor play and pleasure. Because of the steep topography of most coastal town sites, such areas cannot as a rule be established within town limits but must be placed on adjacent national forest lands. Attractive national-forest areas have been set aside for groups of summer-cottage sites and leased to town residents. Camp and picnic grounds have been developed and fitted with shelters, tables, fireplaces, water systems, and simple play paraphernalia.

Winter sports, especially skiing and skating, are definitely on the up in Alaska. A number of new play areas have been made accessible recently by roads and trails. The Forest Service has sought help from organized, unlimited-membership groups, such as ski clubs, hiking clubs, Scout organizations, and rifle associations to supervise orderly use.

Juneau has the largest gold mines in Alaska and an excellent library and museum of local history. Here woods trails for hiking lead out of town and facilities for quiet boating on fresh or salt water are available. Thirty minutes distant by highway is the Mendenhall Glacier. This ice mass descends a steep valley 2-1/4 miles wide. About 125 years ago, it is evident by the vegetation, the face of the glacier extended to tidewater. Wild goats can be seen at times on the grassy upper slopes of ridges flanking this glacial valley.

Twenty miles south of Juneau by launch is a very active glacier—Taku, fronting on the sea. Great blocks of ice drop from its mile-wide, 250-foot vertical face at frequent intervals during the day, and in the form of deep-blue, fantastic-shaped bergs, are carried down the fiord by the tides. This glacier is steadily advancing its front into the sea channel; a rare phenomenon, for most tidewater glaciers in Alaska are now receding.

Tracy Arm, situated 50 miles south of Juneau by launch, is an outstanding fiord—a clean-cut chasm extending for some 20 miles into an ice-capped mountain range. In the same locality is Port Snettisham with three beautiful hanging lakes, all lying 1,000 feet or over above sea level. Their waters pour into the bay over high waterfalls and multiple cascades.

Sitka is 50 minutes by airplane from Juneau. For 68 years prior to the purchase of Alaska by the United States, it was the capital of Russian America. From Sitka the Russians carried on their extensive sea otter- and seal-hunting operations, and their attempts to colonize the New World. Among the interesting relics of their occupation is a cathedral where services are still conducted for whites and Indians holding to old Russian creeds.

FOREST PLANNING . . . Of the total national-forest area of approximately 21 million acres only about 7 million acres have timber cover. The remaining 14 million acres are made up of muskeg, other open lands within the timbered zone, brush, grass, barren peaks, snow fields, and ice caps above timber line. This large untimbered area will be undisturbed by commercial forest activities. Of the total timbered lands, at least one-third is unlikely ever to be invaded by logging operations because of low commercial timber values. These low-quality forests are often as pleasing in appearance as commercial stands and are usually important as habitat for game and fur animals.

The great bulk of the national-forest commercial timber is confined to a strip from 3 to 5 miles wide along tidewater; but with orderly cutting, and reproduction of cut-over areas assured by timber-management plans, forest devastation with huge areas of unsightly brush or barren lands may be avoided. Lands of unusually high aesthetic and recreational values, in some cases covering thousands of acres, will be left intact.

|

| The same need exists in Alaska as in the continental United States for outdoor play and pleasure. WARD LAKE RECREATIONAL AREA, TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST, ALASKA. F-368239 |

Recreational planning on Alaska national forests resolves itself, then, into first providing for local community recreation. This presents no important difficulties. A substantial start on a program has already been made. To prevent conflicts between local outing activities and other national-forest uses, such as homesteads, fur farms, Indian claims, and logging operations, suitable lands have been reserved near towns and industrial centers.

The second consideration in recreational planning is coordination of forest recreation, wildlife management, and the preservation of scenery in localities where timber cutting is under way. This offers complicated problems that can be solved only by following definite policies and practices. Areas carrying commercial timber but having scenic and other paramount recreational values will be withheld from logging operations entirely or subjected only to such cutting as will not detract materially from the higher value. For instance along the narrow channels of main steamer routes, a light selective logging, not greatly altering the appearance of forest cover, may be feasible.

Only about 22 percent of the total forest area has loggable timber. Timber-management plans prescribe a tree-growth rotation averaging around 85 years, so that, in general, slightly more than 1 percent of the commercial-timber area will be cut over in any 1 year. No serious conflict need exist between lumbering and wildlife on the national forests.

The maintenance of numerous deer involves no difficult problems. The remote high-country ranging habits of the mountain goat give little chance of conflict between this animal and resource development. But the large wilderness animals, mountain sheep, moose, Alaska brown bears, and grizzly bears, constitute game resources of such dominant interest that special consideration must be given them in plans for land and resource use of every kind. Management plans of a type now in effect on Admiralty Island for bear will be established on all commercial timber-management units where wildlife is important.

The possibilities of a large newsprint production, a potential expansion of lode mining, fur farming, and other resource uses, will likely lead to greatly increased commercial developments in Alaska's national-forest regions during the next two decades. But all increase in settlement that can possibly be foreseen will perhaps leave three-fourths of the total land area undeveloped. The extensive back areas, so well suited to the frontier type of recreational use that is characteristically Alaskan, will be largely devoted to that purpose.

There are as yet few garish and clamorous invasions of the forest calm in southeast Alaska. Most developments fit into the scene. But to be sure that nature is not outraged in the coming commercial expansion, careful, integrated planning is required. The job is being approached from both the regional and local points of view.

Because of the steepness of the country and the excessive costs of clearing land, large-scale agriculture in southeastern Alaska is unknown. People do, however, raise vegetables, berries, and gorgeous flowers in small patches on cultivatable land near the coast.

Home sites are restricted to these better lands and to areas capable of supporting groups of homes rather than single scattered ones. Town sites and group home sites are selected and subdivided to concentrate commercial fishermen, miners, lumbermen, and others in properly located and sizable communities. Already island fox farming with free-running animals is passing from the picture, and isolated fox-farming families are being concentrated on 5-acre tracts along roads near towns where pen-raised fox farming offers better chances of success. In brief, land-settlement policy on the national-forest area seeks primarily to avoid isolated settlement. Because of the adverse effect of isolation on human welfare and the difficulties of providing essential social facilities, such as mail service, schools, and roads, to scattered home sites, group settlement is encouraged. This helps also to safeguard recreational values and encourage wildlife.

A third consideration in forest planning is to provide a complement for, rather than to duplicate, the pleasures already available to outdoor lovers in the continental United States. The tourist industry, particularly that involving stop-over tourists, appears to offer some chance for expansion in Alaska. This recreational industry and industrial expansion should be coordinated so that the Territory will derive the economic benefits of both. It is not believed necessary to stifle either in order to have the other. Alaska has room enough for all.

TOURISTS . . . Visitors to southeastern Alaska must love water and travel on water. They must be content with much fog and rain; to wait for the views good weather brings. Extensive land travel for the average visitor is not practical. Most people seldom get more than a few miles from their boats. A week of clear weather, without fog or rain, is exceptional. But when good weather comes, the views of snow-clad mountains, 75 miles of them, are never to be forgotten.

Alaska is not likely to be called on, in any predictable future, to entertain great multitudes of visitors. No rail or highways connect with the United States, but airline transport is probable in the near future. Considerable time and expense are involved in reaching Alaska. Travel within it is mostly by boat and airplane.

More than half of the people who now visit Alaska are on round-trip pleasure cruises of about 2 weeks, out of Seattle, Wash., and Vancouver, B. C. As their time ashore is limited to stops of a few hours at principal coastal towns and other seaside points of interest, caring for their needs on national-forest lands presents no difficulties.

Some of Alaska's visitors come for extended visits. They usually have a definite reason for staying over—most frequently, perhaps, because Alaska has something unusual to offer in their particular field of interest. Many want to experience for a while the zest of frontier living. The explorer seeks to enrich geographic knowledge of this new land. The high mountains and the unique game animals challenge the mountaineer and the big-game hunter. The motion-picture and still-camera enthusiasts and the painter are attracted by the scenery and wildlife. The student and the expert in natural sciences come to study the native races, wildlife, rocks, glaciers, volcanoes, northern flora, and many other subjects in this little-explored land. Such present and prospective visitors are but a small fraction of the thousands of forest visitors in the States. But they come here thinking, and what they have to say in their various ways, reflectively, from without, may make in time a real contribution to land-use planning in Alaska.

If this wilderness land is to be more widely used by the people, better facilities than now exist must be provided to bring them here and to care for their wants in town and field. Two bottlenecks now discourage stopover visitors. The first is insufficient steamship service during the summer season. The number of round-trip tourists seeking accommodations is so large that the transportation companies can readily fill their ships to capacity with this class of travelers. Stopover visitors then have great difficulty in obtaining return passage unless arrangements are made months ahead and strictly adhered to. The second serious obstacle is the lack of sufficient first-class hotel accommodations in many ports near entrances to wilderness areas. Interrelated, these difficulties will, no doubt, have to be solved together as parts of the same problem. They are, perhaps, matters that must be left to private initiative.

The Federal Government is building roads and trails, but more than that is needed. There should be simple but comfortable lodges adapted primarily to water trips, transportation from steamship ports to these lodges, and guide service for the back country. Planned trips for small parties could be arranged by the operators of these lodges, combining trout fishing, seeing the Alaska brown bear, clamming, sea fishing, visits to an Indian village, and to glaciers. Areas of national-forest land suitable for lodges and permanent camps can now be leased, provided the facilities are so located and the business so conducted that the natural beauty of this new land is not defaced and defiled.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap14.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |