|

Forest Outings By Thirty Foresters |

|

Part Four

WHAT REMAINS?

Chapter Fifteen

Old Land: Puerto Rico

So it is that the forces that molded the earth have likewise molded humanity. Physiographic variations of the land have everywhere varied the lives of the inhabitants. And man who must follow the earth wheresoever it may lead, must bend to the earth's limitations.

J. H. Bradley, Autobiography of Earth, 1935.

PUERTO RICO is an island lying between the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea some 1,100 miles southeast of the tip end of Florida. It is a small island—110 miles long and 35 miles wide. By steamer one can reach Puerto Rico in 4 days from either New York or New Orleans. It is only 7 hours from Miami, Fla., by plane. Whether going by plane or steamer, one enters the island at San Juan, a city of 140,000.

At the close of the fifteenth century when Columbus landed on this island he found a few thousand Indians of the Borinquen race. Today there are 1,800,000 persons occupying a land only two-thirds the size of Connecticut. The island is one of the most densely populated agrarian lands on earth. Agriculture is the first concern of three-fourths of the people. If the present rapid increase in population continues, there will be one inhabitant for every acre by 1945. Then there will be left to provide sustenance less than half an acre of arable soil for each person.1

1There are 16 acres for each person in the United States, 5 of which can be cultivated.

Since the first consignment of sugar left the island for Spain in 1533, the land has suffered. The "jibaros," or subsistence farmers, were early forced out of the cane lands to steep slopes of the mountainous interior where they practiced the destructive "conuco" system of clear, plant, and abandon. The land has been unable to withstand the mining methods practiced for so many years. And of the forests—also mined—not enough is left to supply the local demands for charcoal. Today the soil is, in the main, tired, thin, and poor; and where the soil is thin and used up, society wilts.

|

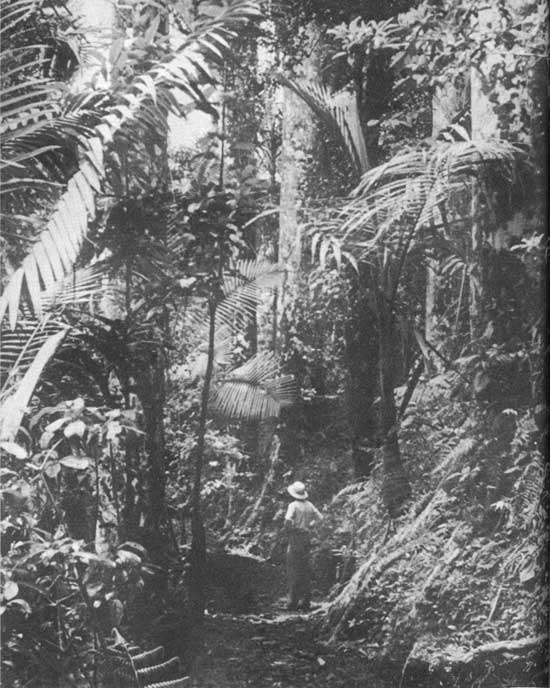

| Giant tree ferns and flowering tree giants with tangled tropical undergrowth ablaze with flaming air plants and wild orchids. CARIBBEAN NATIONAL FOREST, P. R. F-384834 |

The Puerto Rican is one of the most mixed races on earth, but his environment has made him homogeneous. It has helped to subdue the warlike spirit, antipathies, the lust for gold, and to make these islanders tolerant. The gregariousness, the simple hospitality, the high-walled plazas are the growth of a crowded land.

PONCE DE LEON found Puerto Rico a land where "the vine is always fruited and the weather always fine." He called it the "gate of riches." Dense forests covered the land, rivers ran clear, and game was plentiful. Today these forests have disappeared, with the exception of some 15,000 acres of virgin cover in the Caribbean National Forest. Brush, crop, and pasture land have taken their place; yet the island is blessed as few countries are with natural beauty. It is like a pretty peasant girl with the carriage of a queen and the raiment of a dirty child. It is a land of contrasts.

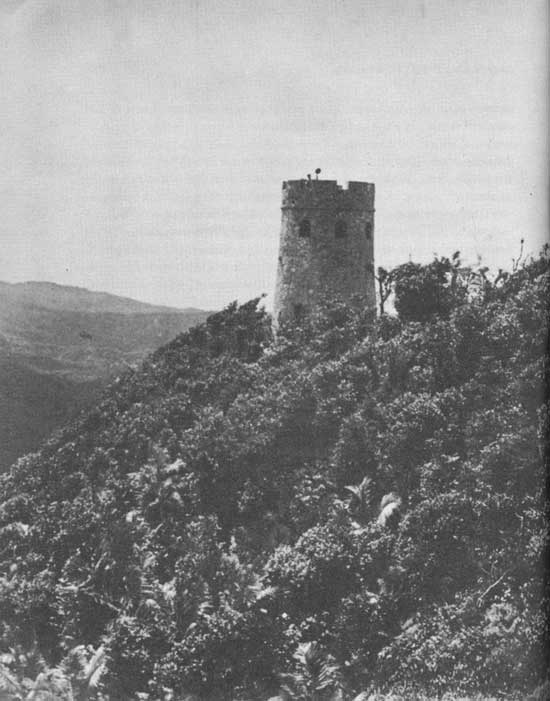

Since October 18, 1898, when formal possession was assumed, when the American Flag was raised over fortifications where the emblem of Spain had flown for nearly four centuries, the new has mingled increasingly with the old. Oxcarts plodding patiently over modern highways turn aside for high-speed busses. Radios blare up-to-the-minute news from buildings centuries old. From the penthouse of a modern, expensive apartment one can look over an ancient plaza to the thick age-blackened walls of a sixteenth century Spanish fort. The battlefield where in 1625 the Spanish drove the Dutch invaders back to their ships is a nine-hole golf course now.

American efficiency was suddenly introduced. A postal system was installed, freedom of speech restored, a resident police force organized, medieval methods of punishment abolished, and Spanish currency was replaced by American money. Free public schools advanced literacy. English was taught and today many speak it fluently. Public health service and medical centers reduced the death rate from approximately 37 persons per 1,000 in 1910 to less than 20 per 1,000 in 1935. The population has doubled in the 40 years since American occupation.2

2This rapid growth has resulted from an increased birth rate as well as a decreased death rate. Births are 40 per 1,000, more than twice the birth rate of the United States.

The people, as a whole, responded quickly to these improvements and were awarded American citizenship in 1917. But the injections of modern civilization have completely modernized neither the land nor the people. The island still retains innumerable reminders of its four centuries under the Spanish Flag. Spanish architecture prevails. The ancient military road connecting San Juan and Ponce is still the most travelled. Many present-day farmers still turn their furrows with an ox and a crude plow. The people, in the main, still cling to folklore and traditions, to the quiet pastoral life with its swishing machetes and rumbling cane mills, to the warm earth with its smell of cane fields, citrus groves, and ripening tobacco.

San Juan, the island's capital, does show some exterior signs of American influence. Thousands of autos with a proportional number of filling stations, American-style department stores, office buildings, and apartment houses, indicate the influence of "Yankee ideas." But out on the island, back in the hills, the people have changed little. Here the forces that have molded their lives go back beyond the time of American occupation. They are forces as old as the mountains that divide the island, as old as the rivers and wind and rain that created the land—a land of extremes.

THE LAND is of mixed volcanic and sedimentary origin. Soil composition varies by the acre, from the coral sands of the coast to tenacious clays in the interior. Rock formations range from weather-resisting granites on mountain tops to soft, yielding limestones on the north-central coast. And each soil dictates the crop to be grown. Coconuts along the seashore, pineapples and citrus fruit a little farther inland, sugarcane on the intermediate coastal plains, tobacco in the high valleys, coffee and bananas, pasture, and brush-land in the hills proper—thus, generally, the soil determines its crop throughout the island.

The Cordillera Central Range, rising to 4,400 feet, divides the island lengthwise, throwing two-thirds of the drainage northward toward the Atlantic coast and one-third to the south coast into the Caribbean Sea.

The Luquillo Mountains on the east end of this divide stand full in the way of moisture-laden trade winds. There, on the north slopes of the Caribbean National Forest, 200 inches of rain falls on an average each year. Many of the moist winds are swept along the entire north side of the central range and provide ample water for all. But on the south coast, across the divide, rainfall is meager, a scant 20 inches in some localities. There, water has to be collected in rain barrels, stored in lake reservoirs, or pumped from deep wells and distributed by irrigation ditches to fields and stock.

Water is life in hot countries, and much water is needed to keep the people alive. Several large rivers, numerous small streams, and innumerable rivulets are sufficient while it rains; but when dry weather sets in the steep slopes run dry. Rivers become trickles over stony beds. The watercourses play an important part in the life of the people. Roads from the coastal areas parallel the larger ones and follow the easier topography of their valleys into the rugged interior. Rivers carry to the sea impurities which would otherwise be a potential menace to people in times of epidemics. In those same rivers they wash their clothes, slake their thirst, water their stock.

Visitors consider the climate of Puerto Rico one of its greatest assets. Year-round temperatures average 76° F. Strong contrasts, marking the seasons of the North are lacking, yet the climate has little of the monotonous heat characteristic of a tropical or subtropical country. The variation in temperature results mainly from differences in elevation, absence of lengthy wet and dry seasons common in parts of the Tropics, and to the cool trade winds that bring changes of humidity and billowy clouds.

But occasionally (four times since 1898) a tropical hurricane hits the island and does tremendous damage. Fortunately few lives are lost, thanks to advance storm warnings issued by the United States Weather Bureau and to well-constructed storm shelters. These severe storms influence the habits and philosophy of the rural Puerto Rican. He dates his birth, marriage, and death by their occurrence. He knows his house and most of his worldly goods will be destroyed, so he is content with little, to hold his losses small. And even though he names individual storms for religious saints, the hurricane is a curse, ]the name itself coming from the Borinquen Indian word hurican, meaning "evil spirit."

FIESTAS . . . With such a background of contrasts and extremes working through the centuries to shape and mold the character of the present-day Puerto Rican, it is little wonder that he continually seeks a compromise—a middle ground. But the forces are strong, odds are against him, and, by and large, he remains very rich or very poor.

Puerto Ricans are pleasure-loving people. The fortunate few may take their families to the movies, casino, dance places, to the club, to a horse race, or a baseball game. The country people may indulge in cock fighting, domino and card playing, or attend a barbecue. Visiting or calling upon neighbors is a pastime common to all. They are socially inclined, fond of music, and whenever a group gathers for play or relaxation, a "fiesta" is in the making. The fiesta is the outstanding form of native recreation. It is spontaneous and unorganized; the participants take their pleasure as they do their food, as part of their everyday life.

The average Puerto Rican lives so at elbows with his fellows that the only forms of recreation ordinarily available are of the passive sort. He must be an onlooker rather than a participant. Inactively he has his enjoyment and diversion but gains few if any physical benefits. Furthermore, he is most likely to live in the relatively hot lowlands. Any climatic relief or change must be found on the island itself. His only resource is to go to the mountains, where climate and environment unite in offering stimulation.

The plight of two-thirds of the population, the laboring class, whose average weekly wage in 1937 was $4.76, is today a major problem facing the insular and Federal Governments. Hunger appears to induce not revolt but apathy, inertia. But there is a danger of people, whose roots are in the land, remaining idle during their leisure and holing up in cities too long. Puerto Rico's high homicide rate is one result. It is imperative then that since the public forests offer the only conditions permitting real rest and change, the first objective should be to furnish outdoor recreation of a type available for the low-income masses. Forest recreation for the masses should be predicated upon group gatherings—the fiesta moved to the forest.

THE PUBLIC FORESTS have within their boundaries the finest opportunities for relief from the crowded lowlands found anywhere on the island. Under the administration of three agencies, but coordinated by central control, they cover nearly 85,000 acres.3 With the exception of the insular mangrove forests on the coasts, these public forest lands are confined to the high watersheds lying above 1,000 feet elevation.

3The Caribbean National Forest (2 units) contains 24,680 acres; the insular forests (7 districts) 39,600 acres; the Puerto Rican Reconstruction Administration forests (5 units) 20,650 acres; all public forest land on the island amounting to 84,930 acres.

The national forest, created by Theodore Roosevelt in 1903, includes lands formerly owned by the Spanish Crown and ceded directly to the United States Government by the Treaty of Paris. Because of their inaccessibility they were not parceled out as land grants but were held in Crown ownership. These lands were unexploited and thus the only large stands of virgin forests on the island were unintentionally saved for posterity.

The inaccessibility of the public forest land barred the masses. A rough and difficult trail did lead to the top of one peak, El Yunque, in the Luquillo Mountains, but it was used by only a few hardy souls. The national forest, in the main, remained as remote and untrodden as in the days of Columbus.

Recent development and consequent use of forest lands for purposes of recreation began when funds and manpower became available through the CCC and other emergency programs in 1933. The essential first step was to build motor roads opening up the forest interior. Because of steep slopes, rock faults, and cliffs, thin mica-filled soils that get as slick as soap when wet, and the tremendously heavy rainfall, landslides and wash-outs presented many engineering problems, especially on the new road traversing the national forest. The supervisor of the Caribbean National Forest directs the entire program.

That the scenic and climatic advantages of the area opened to the public by this road justified its construction is evident. In fact, public response began before the road and recreational development were well under way. As many as 1,000 persons a day seeking an outing was not unusual. After 5 years of work, the road has finally been connected across the divide. Now the recreational center is easily accessible to more than a million people living within 50 miles on both the northern and southern coasts. Much heavier use may be expected in the future.4

4Within a radius of 25 miles are 592,000 people with 262,000 living in cities. Within 50 miles are 1,019,000, of whom 348,000 are urban dwellers.

THE LA MINA RECREATIONAL AREA, 500 acres of breathing space in the Caribbean National Forest, is in a setting to be found nowhere else in the American Tropics. A combination of breath-taking panoramic views of palm-covered mountain slopes, timbered ravines, rocky gorges, cliffs, and waterfalls; giant tree ferns and flowering tree giants with tangled tropical undergrowth ablaze with flaming air plants and wild orchids; teeming with chameleons and tiny but vociferous tree frogs; all at 2,000 feet above the hot lowlands. Here, the air is always crisp and invigorating—a truly air-conditioned tropical forest.

Conditions are ideal for the family group. Rainproof shelters are necessarily provided as protection against the sudden, torrential downpours. The rain comes down in bucketfuls for several minutes, the storm passes over the mountain, and the sun comes out. Benches and tables, whipsawed from native timber, were planned with the fiesta in mind. The favorite holiday food is roast pig. Barbeque pits have therefore been made available and charcoal is furnished free.

There are two beautiful swimming pools fed by cool mountain streams. Well-graded hiking trails lead from the parking areas to outstanding points of interest and to mountain peaks.5 Comfortable cottages, with nearby dining-room facilities, are available for persons wanting overnight or weekend accommodations. People who can afford a longer escape from the heat of coastal towns can lease cottages from the Forest Service.

5In 1938 more than 10 miles of hiking trails, with observatory towers and trail shelters, were provided in the La Mina Area alone, and a total of 60 miles in all public forests.

Wildlife is sadly lacking throughout the island because of the density of population, scarcity of forest cover, and the abundance of mongooses and rats. Hurricanes have also exacted their toll.

But on the public forests, under favorable natural conditions and protection, game is coming back, especially birds. The Puerto Rican parrot, once believed to be extinct, is becoming increasingly abundant on the national forest. Scale pigeons, tanagers, and several other species of birds indigenous to Puerto Rico are increasing in numbers. In the deep forest interiors some boa constrictors may be found. But there are no poisonous snakes and few obnoxious insects to cause the visitor concern.

Tropical plants and trees grow in amazing numbers throughout the national forest. More than 300 tree species, 21 different wild orchids, and 500 varieties of graceful ferns, some growing 30 feet tall, have been identified. Many others have yet to be named. On the highest mountain slopes in the Luquillos grow dense dwarf forests. Because of thin soil, excessive moisture, and exposure to strong winds, the trees are no taller than a man, yet they are hundreds of years old and identical botanically to giant trees of the same species on more favorable sites. Many are varieties that exist no other place in the world. Their trunks and twigs are covered with dripping pendants of saturated moss.

|

| Rainproof shelters are necessarily provided as protection against the sudden, torrential downpours. CARIBBEAN NATIONAL FOREST, P. R. F-384760 |

Other recreational areas are necessary to supplement the La Mina development, located in the eastern end of the island, if a well-rounded recreation program is to be within reach of the entire population. The Dona Juana area in the high mountains of the Toro Negro Unit of the Caribbean National Forest, opens up similar recreational possibilities of benefit to people living in the central part of the island, especially around Ponce, on the hot dry southern coast. Roads with connecting trails through the Maricao Insular Forest, and a modest degree of recreational development, have opened the scenic and climatic resources of that forest to the people of Mayaguez and other western towns.6

6There are 688,000 and 602,000 people living within a 25-mile radius of Dona Juana and Maricao Recreational Areas, respectively.

Some 40 miles west of Puerto Rico, midway to Santo Domingo, is Mona Island; 14,000 acres of brush-covered limestone, honeycombed with deep caves and walled by precipitous cliffs 200 feet high. Fishing in the offshore waters is said to be the best in the West Indies. Barracuda, tuna, sail fish, and king mackerel can be taken by the sportsman. Wild goats inhabit the limestone cliffs and afford good hunting.

FUTURE USE of recreational areas in Puerto Rico will be limited only by their capacity to handle the crowds. Present facilities are taxed, yet it is believed that the 55,000 visitors on public forests in 1938 represent only the beginning of forest use. Ten times more people in proportion to the population visit national forests in the States. It is conservative, then, to assume that within a few years, visits to forest areas in Puerto Rico should become increasingly popular. Plans call for construction of 18 additional recreational areas during the next 10 years.

Tourist visits, accelerated by insular government leadership in travel promotion, should not conflict with normal recreational use. Most tourists visit the island during the cooler months when local use is at low ebb. There is every indication that more continentals will visit the island when they become better acquainted with the pleasures offered and the ease of getting to the American Tropics, and when more adequate tourist accommodations are available. Concrete proof of this is given in the first annual report of the Puerto Rican Institute of Tourism, covering the fiscal year ending June 30, 1938, which shows that more than 29,000 visitors were attracted during 1937-38, compared with 14,500 the previous season. An important byproduct of these visits will be the income derived by the island. The institute estimates the daily expenditures of cruise passengers at $15. On that basis more than $440,000 was left by the 1937-38 excursionists.

Tourists are entranced when motoring up the newly built forest highway to the La Mina Recreational Area. Magnificent vistas of mountain and sea unfold with each turn. Winding through depths of luxuriant tropical forests the road passes towering cliffs and misty waterfalls. About one in eight persons using the national forest is from outside the island; practically every foreign country has been represented.

The paramount objective of the forest program of the insular and Federal Governments is to develop every acre of public land to its highest use so the needs and welfare of a majority of the island population will be served.

Timber production and watershed protection will be the paramount use of forest land. The aggregate area required to meet the recreational needs of the people will not cover more than approximately 5 percent of the total forest area. But until reforestation has converted the thousands of acres of idle brush and poor pasture land into timber-producing forests, recreation on the existing timbered areas will be an important activity.

On few areas under Forest Service supervision is recreation so compatible with the major uses of timber production and watershed protection as in Puerto Rico. For each 1,000-foot rise in elevation the temperature drops 3° F. Because of this universal fact, practically all recreational developments are in the high mountain areas. Six or ten degrees cooler makes a world of difference in the tropics. Above 2,000 feet, where most recreational areas are located, forest trees are chiefly those of species most valuable for their soil-holding ability. Commercial stands of timber are, for the most part, located at lower elevations, and timber cutting will be confined mostly to forests growing below areas of heavy recreational use. Only 1 species out of 50 of commercial importance, tabonuco, grows in stands sufficiently dense to justify clear cutting. Logging over most of the forest will, therefore, be of a highly selective character, and there will be but slight disturbance of natural environment.

With land so scarce, in Puerto Rico, every acre must count. In addition to providing breathing space for the masses, the Forest Service must provide living spaces for hundreds of families who never have owned the land they tilled nor the crops they raised. This land is now national forest land, but the people cannot be dispossessed there is no place for them to go. The land they occupy is worn thin and in need of rebuilding—of the soil-holding and building power of forest trees. But the people have to live, to plant crops, to hold body and soul together.

The Forest Service has therefore established the "parcelero" system, under which a plot or parcel of denuded public land, some 5 to 10 acres, is allotted without title to each family. The family worker plants forest seedlings under careful supervision, and grows his sustenance crops between the rows of growing trees. After, say 2 years, the tree canopy closes and shades out vegetables. More tolerant crops, such as coffee and bananas, which provide the family with food and income, are then substituted. In this way the "parcelero" system re-creates the forest, builds up worn-out soil, gives human sustenance, and at the same time imparts hope for the future to each parcel farmer and his family.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

forest_outings/chap15.htm Last Updated: 24-Feb-2009 |