|

Centennial Mini-Histories of the Forest Service

|

|

Chapter 10

The Economic Legacy of Early Foresters

When forestry emerged as a profession in the United States in the first decades of the 20th century, many early practitioners were relying on European techniques. The managed forests of Western Europe were developed in response to the depletion of old-growth timber supplies. Based on this forest history, the advocates of scientific forestry in the United States warned that destructive timber practices—including the absence of sustained-yield management—would lead to a timber famine. It came to be a cause of professional forestry in the United States to ward off the inevitable famine by increasing forest productivity (by increased growth of supply through removal of decadent stands and reforesting areas) to meet predicted future demand. The resulting increased supply of timber was to be managed according to principles of scientific conservation or wise use.

The demise of the timber industry in the Great Lakes over a period of a few decades in the late 19th century gave credence to foresters' fears of a timber famine at a time when the lumber industry was a major contributor to the national economy. Although a true scarcity of timber never happened, the potential for one became a legacy of timber management in the Forest Service. According to historian David Clary (1986), this explains the difficulty of the agency in adjusting to pressures for a reduced timber program.

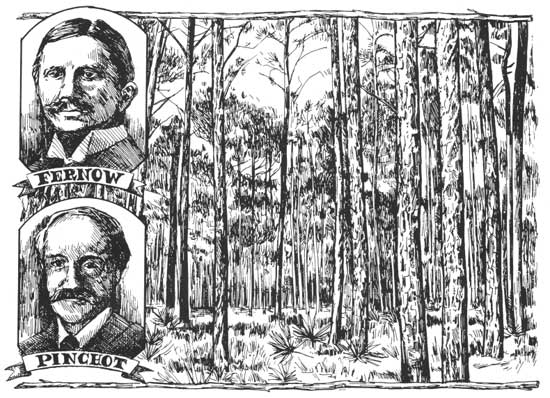

To prevent a future "timber famine" and to encourage private timber holders to practice sound forestry the economics of sustained-yield management was stressed by pioneer foresters Fernow, Pinchot, and Schenck, who succeeded Pinchot in 1895 at the Biltmore estate forest. Fernow, however, believed that the private sector lacked the incentive to practice scientific forestry and in his Economics of Forestry (1902) argued for Government control. In the view of Fernow and Pinchot, creation of Federal forest reserves beginning in 1891 was only a first step in forest conservation. Government foresters Fernow and Pinchot originally were restricted to advocating scientific forestry to the private sector. It was not until the Federal forest reserves were created that they could begin to demonstrate to private industry the economic merits of sustained-yield forestry, especially after passage of the critical 1897 Organic Act, which defined the purpose of the reserves and established their management.

Although several authors claim credit, the 1897 Organic Act reflects Fernow's language in its final form. He had recommended in his 1891 Annual Report to the Secretary of Agriculture that the reserves be managed for "preservation of waterflow and continuous timber supply," with scenery and wildlife secondary concerns. The Department of Agriculture's foresters now had the authority to practice Government forestry. What finally became policy of the Forest Service in 1905, however, reflects the stamp of Fernow's replacement Pinchot. For example, Fernow was trained in the long-domesticated forests of Germany and did not regard fire and grazing to be subjects of concern to the science of forestry. Pinchot was more aware of the North American forest situation, which involves the agency in both grazing and fire control. This and other professional and personal differences led to an estrangement between the two foresters, but they remained united on the important need of forestry to show a profit, the only incentive that would induce the private sector to practice sound forestry.

Contrary to the cartoon image of rapacious timber barons fighting the creation of Federal forest reserves, some sectors of the industry supported reserves because they would "limit new competition and stabilize the market" (Robbins 1982:24). In fact, one reason why timber sales from national forests generated little early revenue (contrary to the dream of Pinchot to demonstrate that forestry paid) for the Forest Service was pressure by the industry not to flood the market. The adequacy of private supplies, contrary to earlier Forest Service projections, was such that at the beginning of World War II less than 2 percent of the Nation's lumber came from agency timber sales. However, the rapid population growth and housing boom in the next decades contributed to a decline in private timber in the Pacific Northwest and to the growth of Government timber sales in response. But still, the predicted national wood famine never happened. What did happen was that certain ages and types of wood became scarce, leading to the debate over the future of old-growth on national forests. In recent decades the agency has fulfilled its historic mission of being a source of supply of wood. But in an era when private industry practices sound forestry, the mission of the agency is debated: Do we want the managed forests of Europe or the wilderness that was present in North America only 300 years ago?

References

Clary, David A. 1986. Timber and the Forest Service. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

Robbins, William G. 1982. Lumberjacks and legislators: political economy of the lumber industry, 1890-1941. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

FS-518/chap10.htm Last Updated: 19-Mar-2008 |