|

Centennial Mini-Histories of the Forest Service

|

|

Chapter 13

Forest Reserves and Forest Rangers

Passage of the Federal Forest Reserve Act of 1891 gave the President authority to set aside timberlands from the public domain, but at the time the purpose of the reserves remained a matter of congressional debate. Roughly 40 million acres were established as reserves by 1897, the year Congress finally defined the purpose of the reserves ("watershed protection and source of timber supply for the Nation") in the Forest Management ("Organic") Act. The act also gave the Secretary of the Interior authority to regulate occupancy and use within the reserves, develop mineral resources, provide for fire protection, and permit the sale of timber. It was left to the U.S. Army to police Yellowstone Park from the years 1886 to 1918. But beginning with the creation of Yellowstone Park Timberland Reserve on March 30, 1891, supervising the reserves became the responsibility of the Department of the Interior.

Bernhard Fernow is credited with providing the model—adapted from the Prussian system of state forest management—in an 1891 report on how to manage the reserves. The task actually was undertaken by the Department of the Interior until 1905—first by the General Land Office (1891-1901) and then by the Interior Forestry Division (1901-1905) under Filbert Roth (1858-1925), who earlier had worked for the Department of Agriculture under Fernow. The two departments' forestry divisions cooperated on forest reserve programs.

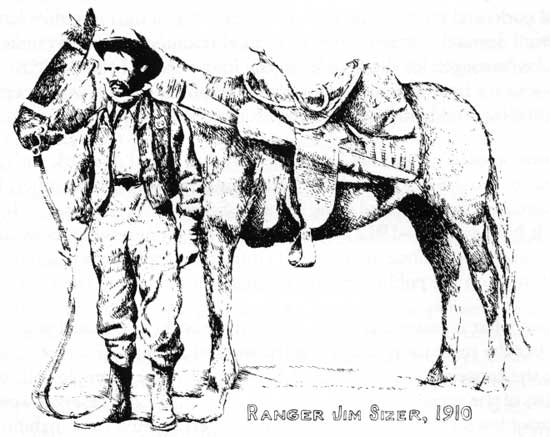

Early custody of the reserves by the General Land Office was based on a hierarchy of State superintendents, reserve supervisors, and rangers who managed districts within the reserves. The key to success of forest reserve management was the ranger.

The word "ranger" was an American variant of the ancient French verb for "rover," introduced to England by the Normans who came with William the Conqueror in 1066. Rangers were the game wardens on the Royal Forests of England and became the foragers/scouts of colonial expeditions in Virginia in 1716. The forestmaster of Prussian forestry became the forest ranger or protector of the reserves after 1891. Beyond this vague notion of protecting the reserves, the actual duties of the first rangers were rather unclear to all concerned.

One of the early rangers was Edward Tyson Allen (1875-1942). He was hired an $50 per month in 1898 by the General Land Office and sent west to Washington State to assume the post of ranger on the Washington Reserve (now the Gifford Pinchot National Forest). After he reported to his supervisor in Tacoma, Allen waited for instructions, only to be told: "That letter [you have] appoints you as a forest ranger, doesn't it? It is signed by the Secretary of the Interior, isn't it? Well, you are now a forest ranger—so go out and range!"

Allen helped set the future trend for rangers by departing for his district, buying a horse, and exploring the area until he knew it in detail; he then proceeded to define his job while doing it as he saw fit. Later in 1902, he helped Roth at the Interior Department to prepare a book of regulations that emerged a few years later (1905) as the Forest Service's first Use Book—the regulations and instruction for the use of the national forests (Secretary of Agriculture). The challenge of the job along with the opportunity to earn a steady income in rural areas of the West appealed to venturesome local men. The first-defined duty of the ranger was to protect the reserve's resources. In 1898, William Kreutzer left ranch work to be appointed an early ranger in Colorado "no protect the public forests from fire or any other means of injury to the timber growing in said reserves," or so his certificate of office stated.

By 1899 the USDA Division of Forestry under Gifford Pinchot was expanding rapidly and because of the lack of professional foresters, student assistants were being hired from the few existing forestry schools, especially Yale. By 1901 the Department of the Interior's Division of Forestry and the Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Forestry divided the task of Federal forestry. Interior personnel patrolled the reserves and Agriculture foresters provided technical management plans. The Forest Reserve Manual of 1902 regulated timber use and grazing. The enforcement of grazing regulations was to be a constant challenge for many rangers.

The job of gaining the cooperation of forest users by earning their respect fell to the district rangers. Accustomed to taking timber and forage from adjacent public lands at will, local forest users did not easily accept regulation. The employment of local men as rangers helped, because these rangers could draw on their common background to explain the need for rules to their friends and neighbors. Knowledge of local customs sometimes extended to local language. The 1906 Use Book section on rangers states that those employed in Arizona and New Mexico should know "enough Spanish to conduct reserve business with Mexicans" [sic].

By 1905, with the transfer of jurisdiction of the reserves to the Department of Agriculture, the Bureau of Forestry accepted transfer of many of the early Government Land Office field people and mixed them with its own staff, including the numerous student assistants. In 1901, there were 81 student assistants on the 179-member staff of the Bureau of Forestry. The Forest Service, to its credit, brought out the best in its rangers—many of the eastern "dudes" soon were as adept at western ways as the local rangers, while more than one western-born ranger was promoted to top management. A further factor in selecting rangers in 1905 was the extension of Civil Service authority to the forest reserves. The Forest Service—the new name for the former Bureau of Forestry—developed the first exams (written and practical) for rangers by May 1906. The physical standards demanded then would not apply today; early recruitment posters stated bluntly: "invalids need not apply." Rangers were expected to "build trails, ride all day and night, pack, shoot, and fight fire without losing (their heads)." New rangers received a salary varying from $900 to $1,500 per year, out of which they bought a horse, sidearms, and clothing, to be the lone steward of several hundred thousand acres. As described by Robert J. Duhse (1986:7): "The ranger in his district was often the only policeman, fish and game warden, coroner, disaster rescuer, and doctor. He settled disputes between cattle and sheepmen, organized and led fire fighting crews, built roads and trails, negotiated grazing and timber sales contracts, carried out reforestation and disease control projects, and ran surveys." Injury and even death was the fate of more than one early ranger.

In was not until the mid-1930's that the Forest Service announced it would no longer make appointments at the professional level without a degree in forestry or a related field, a move that ended the era of the self-taught, "rugged outdoorsmen" in the agency. Of course, not all those early rangers were alone; many were married and their wives acted as their husbands' unpaid assistants, performing clerical and technical duties such as tree planting and fire control. Today, it is not unusual for the district ranger to be a woman, with the further change that she may have a staff of 40 and carry a laptop computer instead of a pistol into the field. The challenge of the office is no less, and it may be that some rangers today envy early rangers their solitude and freedom.

References

Burns, John. 1980. "Invalids need not apply." Persimmon Hill 2 (Spring) City, State: National Cowboy Hall of Fame and Heritage Center: 56-63.

Duhse, Robert J. 1986. "The saga of the forest rangers." Elks Magazine July-August.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

FS-518/chap13.htm Last Updated: 19-Mar-2008 |