|

Centennial Mini-Histories of the Forest Service

|

|

Chapter 19

Wilderness and Recreation in the National Forest System

Timber and water were the only two resources on the Federal forest reserves that were officially sanctioned for Government control in the Forest Management Act of 1897. The various provisions in the act, however, show the mixed agenda of its sponsors. For example, the act opened the reserves to mining claims, prohibited inclusion of agricultural lands in reserve boundaries, and allowed commercial sale of timber. It ignored forage, recreation, and wildlife; forage because allowing grazing on reserves was still being debated, recreation because it had few advocates, and wildlife because it was unclear if the States or the Federal Government had legal authority for wildlife on the Federal forest reserves. Yet, it is clear that resources other than timber—and even watershed protection—were on the minds of late 19th century supporters of the reserves.

Writing in Appleton's Popular Science Monthly (February 1898 issue), Charles D. Walcott, director of the United States Geological Survey, stated that there were practical and "sentimental" interests supporting forest reserves. Those who depended on the reserves for their timber supply or irrigation water had practical reasons. Those people whose lives were not directly dependent on the reserves believed that it was "worthwhile to protect the animal life of the forests, and to set aside areas where in the future the crowded population of the nation may have great public parks open to all for health and sport." Such thinking on the importance of wildlife and recreation helped to shape selection of areas recommended for reserve status.

An early example was the Afognak Forest and Fish Culture Reserve, the ninth reserve (and the first one in Alaska), established on December 24, 1892. The primary impetus for the reserve was salmon conservation: "providing a salmon reservation...as a means of keeping up reproduction" (Rakestraw 1981). The U.S. Commission for Fish and Fisheries, a scientific agency established by Congress in 1871 and headed by Spencer Fullerton Baird (1823-1887), was concerned about fish depletion and sent a team to Alaska to investigate the salmon fishing and canning industry. Livingston Stone, a member of the team, proposed a salmon park to preserve one area of natural reproduction from being fished out; he presented his proposal in a paper to the American Fisheries Society that was later reprinted in Forest and Stream, the influential organ of wildlife conservation edited by George Bird Grinnell. At the request of the Commission of Fish and Fisheries, President Benjamin Harrison, by executive proclamation, established the island fish reserve.

Multiple use

Resource conservation on Federal forest reserves (renamed national forests in 1907) under Forest Service management came to include a variety of activities that were never formally mandated until the passage of the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act in 1960. The act directed the agency to give equal consideration to outdoor recreation, range, timber, water, and wildlife and fish resources and to manage them on a sustained-yield basis.

The Forest Service had moved early into range management by supporting regulated grazing on reserves and later permitting it on national forests. Forest Service Chief Gifford Pinchot, in the quest for support for a 1902 bill before Congress to transfer the reserves from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture, had advocated game preserves on reserve lands. The bill was rejected and not passed until 1905, minus the game preserve concept, which had alienated Western development interests. Yet, within 20 years, 20 game preserves were created (with a total of 1.2 million acres) on national forests. This apparent shift was really a matter of early wildlife management, which was fixated on predator control: the game preserves were to keep coyotes and deer away from domestic livestock by restricting them to certain zones.

Outdoor recreation was part of the agency's agenda as well. The public was beginning to use the still-novel automobile for jaunts to nearby national forests for family campouts and cookouts. During 1917, a year after the National Park Act of 1916 established the National Park Service, the Forest Service recorded about 3 million visitors on national forests. The trend was apparent and in that year the agency hired a landscape architect Frank Albert Waugh (1869-1943), to study the recreational potential of the national forests. Competition with the National Park Service over recreational budgets and land acquisitions led the Forest Service to shift toward wilderness management, a step the Park Service ignored due to its mandate to make parks accessible to the public.

Wilderness management

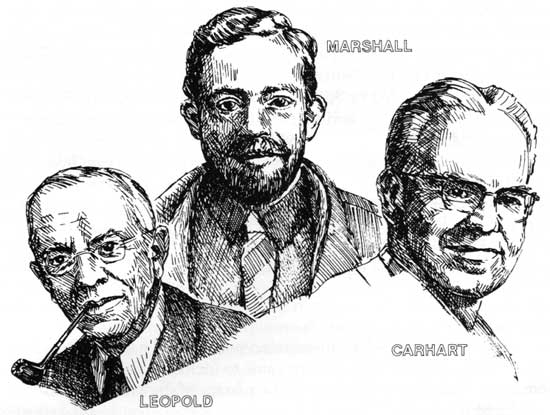

It was not only outside pressures that led the Forest Service into wilderness management, but also internal proposals. Three Forest Service employees who gained later prominence in environmental and recreational lore—Aldo Leopold (1886-1948), Arthur Hawthorne Carhart (1892-1978), and Robert Marshall (1901-1939)—in the 1920's and 1930's designed and helped implement a wilderness policy for the Forest Service.

Aldo Leopold, an Eastern intellectual who loved to hunt and explore the back country, worked for the Forest Service in New Mexico as supervisor of the Carson National Forest. In 1913 he first discussed setting aside remote areas. Two goals to his thinking were his notion of wilderness as part of the national heritage and the importance of studying nature in a pristine laboratory. The latter concern arose through his exposure to the new science of ecology; a field formed in 1915 when the Ecological Society of America was founded.

Concerned with the rapid pace of road expansion after World War I, Leopold recommended when he was assistant district (equivalent now to regional) forester in 1922 that roads and use permits be excluded on the Gila River headwaters. Although his plan was approved in 1924, it was only local, not national, policy. Leopold left the Forest Service in 1928 to take the lead in forming the new profession of game management. Later, building on years of natural history observations, he wrote A Sand County Almanac (1949) in which he developed a land ethic that called for natural regulation of the environment rather than human intervention and control.

Arthur Carhart saw wilderness as a recreational experience. Carhart, a landscape architect hired by the Forest Service in 1919, went on to propose that summer homes and other developments not be allowed at Trappers Lake on the White River National Forest (Colorado). He later surveyed the Superior National Forest in the Minnesota lake region and recommended only limited development. Secretary of Agriculture William H. Jardine signed a plan to protect the area in 1926, and it was dedicated as the Boundary Waters Canoe Area in 1964. Carhart resigned from the Forest Service in 1922 to practice landscape architecture and city planning in the private sector.

Chief William Buckhout Greeley (1879-1955) was willing to endorse the concept of wilderness areas and, in 1926, ordered an inventory of all undeveloped national forest areas larger than 230,400 acres (10 townships). Three years later wilderness policy assumed national scope with the promulgation of the L-20 wilderness regulations (Roth 1984). Commercial use of the areas (grazing, even logging) could continue, but campsites, meadows for packstock forage, and special scenic spots would be protected.

During this period a related activity to preservation of wilderness areas also came to the fore—the concept of research natural areas. The Ecological Society of America was concerned in 1917 with protecting the habitat of rare species of plants and animals. Toward that end it set up the group that evolved into the Nature Conservancy. The Federal Government did not become involved until 1927, when land management agencies began developing research natural areas on Federal lands: the first one, the Santa Catalina Research Natural Area, was on the Coronado National Forest (Arizona).

Robert Marshall, the last of the famed trio of wilderness advocates, was linked with the Forest Service in the 1930's. Raised in wealth on Park Avenue, Marshall played explorer while on hikes in the Adirondack Mountains at his family's summer estate. His love of nature and wilderness exploration influenced his college studies in forestry; he received a master's degree from Harvard Forestry School in 1925 and a doctorate in plant physiology from Johns Hopkins University in 1930. His first Forest Service job was as a research silviculturist at the Northern Rocky Mountain Forest Experiment Station from 1925 to 1928, when he left to study at Hopkins.

A few years later, he was hired by the Forest Service to write the recreation section on the National plan for American forestry, the 1933 "Copeland Report." In that report, Marshall foresaw the need to place 10 percent of all forestlands in the United States into recreational areas, ranging from large parks to wilderness areas to roadside campsites. To ensure that citizens monitor public agencys' protected sites, he helped found and fund the Wilderness Society in 1935. Marshall had earlier worked as chief forester for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, where he supported roadless areas on reservations. He returned to the Department of the Interior when he finished the recreation report for the Forest Service.

In 1937, Marshall became chief of the new Division of Recreation and Lands in the Washington Office of the Forest Service; he died 2 years later at the age of 39. In his short tenure at the Washington Office he drafted the "U Regulations," which replaced the L-20 program under Chief Ferdinand A. Silcox. These regulations gave greater protection to wilderness areas by banning timbering, road construction, summer homes, and even motorboats and aircraft. Marshall had also checked plans for recreational development on national forests to see if they included access for lower income groups, a real concern during the years of the Great Depression.

Marshall, an eccentric and maverick, was famed for both his vigorous 50-mile hikes and his radical political opinions. Unable to endure the diplomacy of working within the bureaucracy, he had planned to resign but then suffered an unexpected fatal heart attack. Likewise, in their own way, Carhart and Leopold felt constrained by the Forest Service and left. Yet, while their tenures were somewhat short, their legacies now make the agency proud that for a time all three wore the uniform of the USDA Forest Service, helping to guide the agency in its management of all the National Forest System's resources.

References

Leopold, Aldo. 1949. A Sand County almanac. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rakestraw, Lawrence W. 1981. A history of the United States Forest Service in Alaska. Anchorage: Alaska Historical Commission, Department of Education, and Forest Service.

Roth, Dennis. 1984. "The national forests and the campaign for wilderness legislation." Journal of Forest History 28(3) July: 112-125.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

FS-518/chap19.htm Last Updated: 19-Mar-2008 |