|

Centennial Mini-Histories of the Forest Service

|

|

Chapter 21

Mining and Forest Conservation

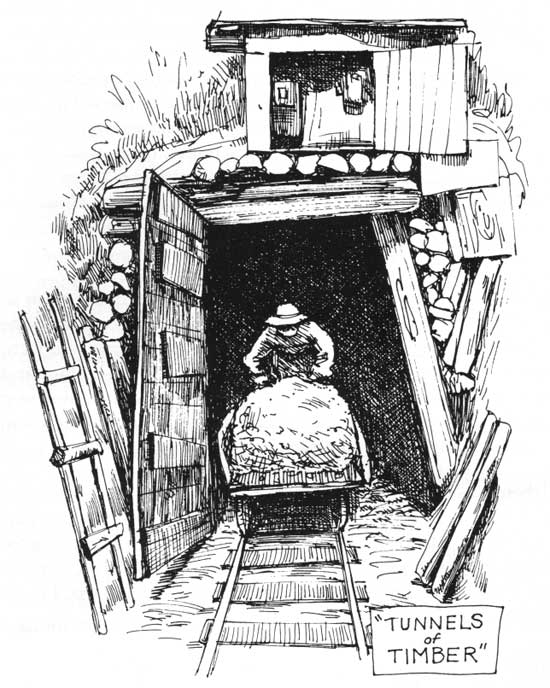

"Prosperous mining is impossible without prosperous forests," Forest Service Chief Gifford Pinchot told the mining industry in 1901 in his quest for support for forest conservation and Federal forest reserves. The linkage between the fortunes of mining and forests in the United States grew following discovery of the rich Comstock silver lode at Virginia City, Nevada. The large size of such works as the Comstock Mine led to a new technique of timber reinforcement in the mine tunnels. Other timber-intensive mining techniques existed then, but in 1860, mining engineer Philip Deidesheimer developed a new timbering technique for tunnels called the square-set. Interlocked sets of framed timbers were used to replace the walls of the mine as the ore was removed, leaving a tunnel of timber to house the mine.

This timber-intensive system was copied throughout the mining industry but used most widely in the West for the large ore deposits commonly found that the region. Forests of the Sierra Nevada were depleted to obtain the estimated 600 million board feet of timber used in the mine from 1860 to 1880. The dependency of mines such as the Comstock on local timber supplies led to the building of sawmills in many new areas of the country. Depletion of local timber in some areas led to a reliance on importing timber by rail and rising expenses as a result.

Efforts were made to reduce costs by using metal supports, but their higher cost (and tendency to buckle) favored the continued use of timbers. This was especially true after creosote-pressure-treatment techniques were invented to help prolong the life span of lumber used in the mines. Later, with the introduction of large earthmoving equipment, open-pit mining reduced use of tunnel mining and the consumption of timbers in the industry. However, deep-level mining still continues and with it the need for timber, and in turn, the existence of bountiful forests.

Pinchot was after more than just having miners conserve lumber when he told them of the relation between forestry and mining. Early opposition to the proposal to create Federal forest reserves came from miners and prospectors worried about restrictions on mining on reserves (Steen 1991). Later, in the debates in Congress over the purpose of the reserves that culminated in passage of the Forest Management Act of 1897, much of the passion settled on whether to allow commercial sale of reserve timber or not.

After the debate was resolved and the 1897 act passed, the first timber sale by the General Land Office (case 1) was to the Homestake Mining Company for timber off the Black Hills Forest Reserve in 1898. Fifteen million board feet were purchased at 1 dollar per thousand board feet. The contract stated that no trees smaller than 8 inches in diameter could be removed and that brush left after harvest had to be "piled."

Federal regulation of mining was not a critical issue in Congress until the Gold Rush of 1849 in California and later rushes in Colorado, Nevada, Idaho, and Montana. These "finds" resulted in claims being worked on public domain lands. To legalize this practice, the General Mining Law of 1872 (which consolidated earlier 1866 and 1870 laws based on models from England and Spain used by the miners in the absence of formal laws) stated that gold, silver, and other minerals in the public domain could belong to the person who found them merely by staking a claim. A claim was set at 2O acres, with no limit on the number of claims that could be filed. A person could hold a claim by performing $100 worth of work each year or by obtaining permanent legal ownership of the minerals and land surface by paying a fee to patent the claim. By having patent on a claim, the owner need not pay any royalties on production. What is most important, however, to being granted legal claim status is the discovery of a valuable mineral deposit.

Congress has since placed fossil fuels (along with other certain minerals such as gravel, sand, and pumice, etc.) under a lease or sales system, but the core of the 1872 law still applies to the national forests and grasslands. The illegal occupancy of National Forest System "mining claims" for purposes such as summer homes, hunting camps, and marijuana farms creates an ongoing conflict with operations approved under the Forest Service Mineral Regulations of 1974.

Gifford Pinchot wrote in the first Forest Service book of regulations for the newly established national forests under the mining section (following the transfer of the forest reserves to the Department of Agriculture in 1905): "No land claims can be initiated in a forest reserve except mining claims, which may be sought for, located, developed, and patented in accordance to law and forest reserve regulations." This wording repeats the section on prospecting found in the 1897 Forest Management Act. The willingness of Pinchot to include mineral resources among the list of resources of the reserves to be used by the people was in part practical politics. It was also the result of his knowledge of the mining industry's needs acquired when he made his first trip West in 1891 to inspect Arizona lands held by Phelps, Dodge & Company to judge if they could be reforested. The 1907 Report of the [Chief] Forester mentioned that three geologists were detailed from the Geological Survey to assist forest supervisors in examining mining claims and that a total of 1,093 mining claims were received that year within national forests.

The transfer of the reserves to the Department of Agriculture from the Interior Department in 1905 removed much of the impediment to regulation of the reserves by USDA foresters but mining still remained under control of Interior. Richard Ballinger, appointed in 1907 to head the General Land Office and elevated to Secretary of the Interior in 1909, differed with Pinchot over coal claims. Ballinger wanted them patented, while Pinchot argued for Federal leasing. Pinchot feared that a coal famine for the Nation would result if the private sector was allowed complete freedom to exploit coal fields without concern for future needs. In response, Pinchot was depicted by the mining industry as out to curtail the right of the citizen to engage in free enterprise—the "small man" was being crushed by Government. By 1910 the dispute between Pinchot and Ballinger reached the point that President William Howard Taft requested Pinchot to resign. Historians now note that the coal debate was only a small part of the conflict over natural resource management policies between Pinchot and President Taft and his people. The struggle between conservation and exploitation continues today in public debates over regulation of natural resources.

References

King, Joseph. 1983. "Mine timber." In: Encyclopedia of American forest and conservation history, vol. 2. Edited by Davis, Richard. New York: Macmillan: 427-431.

Lacy, John C. 1989. "Historical overview of the mining law: the miners' law becomes the law." In: The Mining Law of 1872: a legal and historical analysis. Washington, DC: National Legal Center for the Public Interest: 13-44.

Steen, Harold K. 1991. The beginning of the National Forest System. FS-488. Washington: USDA Forest Service.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

FS-518/chap21.htm Last Updated: 19-Mar-2008 |