|

Centennial Mini-Histories of the Forest Service

|

|

Chapter 7

Rise of the Technocrats: Experts, Managers, and Politics

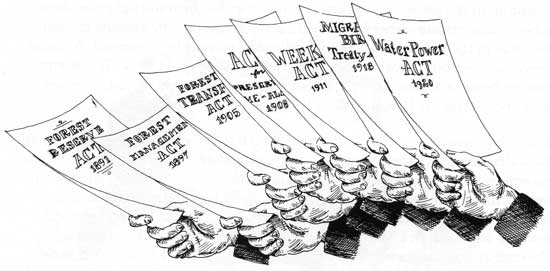

A new agenda appeared in U.S. politics during 1890 to 1920—the "conservation movement." Although its intellectual beginnings were developed in the decades before, during this period the political influence of members of the conservation community made itself felt. By lobbying Congress regarding the future of timber, wildlife, waterpower, and minerals on public lands, members of the conservation movement helped ensure the passage of a flurry of acts, including:

- Forest Reserve Act (1891)

- "Organic" or Forest Management Act (1897)

- Lacey Game and Wild Birds Preservation and Disposition Act (1900)

- Newlands Act (1902)

- Forest Transfer Act (1905)

- American Antiquities Act (1906)

- Act for the Preservation of Game in Alaska (1908)

- Weeks Act (1911)

- National Park Service established (1916)

- Migratory Bird Treaty Act (1918)

- Mineral Leasing Act (1920)

- Water Power Act (1920)

The variety of conservation legislation passed by Congress shows that the goal of creating forest reserves was only part of the conservation movement agenda. In fact, passage of the 1891 act only marked the coming of age of the conservation crusade in national politics. In the years afterwards, it held center stage but then after, enjoying success, began to fade away. Why did the movement capture national attention during this period and what was the motivation of its varied members?

The obvious answer is that members were motivated by the specter of a declining natural resource base. Another answer is that conservation crusaders were caught up in the progressive politics of the time. To them the fight was about public versus private ownership of natural resources; only by keeping natural resources in the public domain could private monopoly be prevented. Another answer comes from historian Samuel P. Hays, who wrote (1959): "It is from the vantage point of applied science, rather than of democratic protest, that one must understand the historic role of the conservation movement."

What Hays is saying is that we cannot isolate the conservation movement from the wider changes that were taking place in the Nation. One major change was the emergence of a bureaucratic management structure in industry and government, a trend that began in reaction to the inefficient and wasteful management practices of the time, whether of timber or of people. A founder of this new way was Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915), an engineer and advocate of "management science." The concept influenced the Forest Service, for the first professional foresters had to justify their presence. Their justification was that forestry was a science and could not be learned just by being out in the woods.

What was the science taught in early forestry schools? It was the gospel of conservation—human intervention in nature to maintain and increase the supply of natural resources. The politics that went with this science were that resources should be managed by objective professionals free from special interest politics. Only in this way could public resources be managed for "the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run," as stated by Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson (1835-1920) in a letter of instruction to Gifford Pinchot at the time of the 1905 Forest Transfer Act.

Reference

Hays, Samuel O. 1959. Conservation and the gospel of efficiency: the progressive conservation movement, 1890-1920. Harvard Historical Monograph No. 40. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

FS-518/chap7.htm Last Updated: 19-Mar-2008 |