|

Managing Multiple Uses on National Forests, 1905-1995 A 90-year Learning Experience and It Isn't Finished Yet |

|

Chapter 1

Introduction

The story of managing multiple uses on national forests is a story about the people who used their resources and why; how national forest managers fitted the uses with each other within the ecosystems that embodied and sustained the national forest resources; and what happened as a result of this use and management. It is a story about national forest uses and users and national forest managers and management. It is a grassroots account of the management of multiple uses within the National Forest System from 1905, when these lands came under the administration of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service, to 1995. The multiple uses include a broad range of national forest policy purposes for outdoor recreation, range, timber, watersheds, and wildlife and fish which were made explicit in the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960. Other land uses such as rights-of-way for pipe and powerlines, public roads, electronic sites, recreation residences, hydropower projects, lodging facilities and resorts, and others were covered by the occupancy and use regulations for national forests under the Organic Act of 1897 (USDA Forest Service 1993).

The forest reserves were initially authorized by Congress and established by Presidential Proclamation in 1891. The reserves were administered by the U.S. Department of the Interior with technical assistance from USDA foresters until they were transferred to USDA under the Transfer Act of February 1, 1905. The forest reserves were renamed national forests under the Act of March 4, 1907, entitled Distribution of Receipts from National Forest Resources (USDA Forest Service 1993).

This story's focus is on the actual uses of national forests and the resource management that national forest managers applied to sustain them and their supporting ecosystems. Its scope is national, but many examples illustrate grassroots use and local, national forest, and regional management. Political issues, policy changes, and national forest funding are addressed where they influence management, but the main thrust of this story is about the users and managers and the uses and resource management as they have been applied on the land. Research and State and Private Forestry, two of the Forest Service's other major program areas, are similarly addressed where they are relevant.

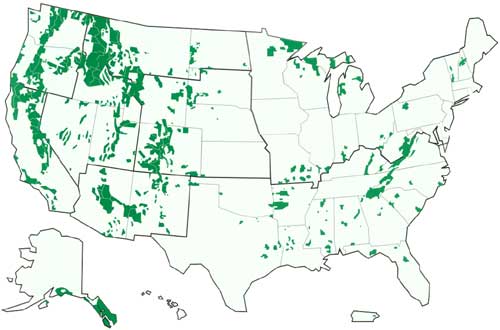

The National Forest System—1998

One-Twelfth of the U.S. Lands and Waters

(click on image for a PDF version)

National Forests: On the Pathway Towards Ecosystem Management

The Concept of Managing for Multiple Uses Emerges

The idea of multipurpose resource use emerged from the Conservation Movement early in the 20th century. Multipurpose planning for water use and development became a widely supported goal. It became the guiding role of the Inland Waterways Commission appointed by Theodore Roosevelt in 1907 to design multipurpose river basin developments that coordinated irrigation, navigation, flood control, and hydropower production uses (Steen 1976). Conservationists supported the Inland Waterways Commission's 1907 proposal for legislation to establish a multipurpose water resource planning agency, which was eventually passed in 1917 but never implemented due to the intervention of World War I and then congressional termination of the Commission in 1920 (Holmes 1972; Fedkiw 1989). Nevertheless, multipurpose water resource development became the rule for Federal river basin developments and, in time, included recreation, wildlife, and fishery uses.

The concept of managing for multiple uses appeared in the Forest Service's argot in the 1920's. Its initial exposition, as "multiple purpose management," appeared in the USDA Forest Service Copeland Report, A National Plan for American Forestry, published by the U.S. Senate in 1933 (USDA Forest Service 1933). Twenty-seven years later, Congress formally defined the management of multiple uses on national forests as national policy in the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960: "National forests are established and shall be administered for outdoor recreation, range, timber, watershed, and wildlife and fish purposes." Congress reaffirmed and expanded this policy in subsequent legislation, most importantly in the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Act of 1974 (RPA) and the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA).

The Organic Act of 1897

The Organic Act of 1897 established the first national policy direction for national forest use and management. The Act was explicit about some national forest purposes and uses. It gave the President of the United States the power to establish national forests on public domain lands "to improve and protect the forest within the boundaries, or for the purpose of securing favorable conditions of waterflows, and to furnish a continuous supply of timber for the use and necessities of citizens of the United States." This clause later became the basis of the general national forest policy for sustained-yield management of forest products and services. The Organic Act specifically required that public lands judged more valuable for mineral or agricultural use not be included in the national forests. The Organic Act permitted prospecting for minerals on national forest lands under existing public mining laws (General Mining Law of 1872) and national forest management guidelines (Pinchot 1907).

Settlers, miners, residents, and prospectors were allowed to use national forest timber and stone for fencing, buildings, mining, prospecting, and various other domestic uses such as firewood free of charge. The Secretary of Agriculture (the Secretary of the Interior before 1905) was authorized to protect the national forests from destruction by fire and depredations and "to regulate their occupancy and use and to preserve forests thereon from destruction." This broad, though simple, authorization was all encompassing and permitted all types of uses not specifically cited in the Organic Act, so long as they were not destructive to the forests. Examples of such uses included rangeland grazing, recreational activities, summer homes and resorts, hunting and fishing, flora and bark gathering, rights-of-way for various purposes (such as roads and powerlines), and many others.

James Wilson, Secretary of Agriculture, transmitted a contemporary practical interpretation of the Organic Act management guidance to Gifford Pinchot, the Chief of the Forest Service, on February 1, 1905 — the day administration of the forest reserves was transferred from the Department of the Interior to the USDA. The guidance, initially drafted by Gifford Pinchot, stated:

In the Administration of the forest reserves it must be clearly borne in mind that all land is to be devoted to its most productive use for the permanent good of the whole people and not for the temporary benefit of individuals and companies. All the resources of the forest reserves are for use, and this use must be brought about in a thoroughly prompt and businesslike manner, under such restrictions only as will insure the permanence of these resources. The vital importance of forest reserves to the great industries of the Western States will be largely increased in the near future by continued steady advances in settlement and development. The permanence of the resources of the reserves is therefore indispensable to continued prosperity, and the policy of this Department for their protection and use will invariably be guided by this fact...

You will see to it that the water, wood, and forage of the reserves are conserved and wisely used for the benefit of the house builder first of all; upon whom depends the best permanent use of the lands and resources alike. The continued prosperity of the agricultural, lumbering, mining, and livestock interests is directly dependent upon a permanent and accessible supply of water, wood, and forage, as well as upon the present and future use of these resources ... In the management of each reserve, local questions will be decided upon local grounds. Industry will become considered first, but with as little restriction to minor industries as may be possible; sudden changes in industrial conditions will be avoided by gradual adjustment after due notice; and where conflicting interests must be reconciled, the question will always be decided from the standpoint of the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985).

The Federal policy at the time was to use national forests for national and regional growth and development — the focal point of Secretary Wilson's guidance and the Organic Act. But local use was also important. Access by local users was a realistic extension of the long-held tradition that the resources in the public domain existed for the benefit of local residents who needed them. This use policy was matched by a concern for the permanence of national forest resources and their mosaic of ecosystems; their use was to be balanced with a concern for their protection from fire and destruction and sustaining waterflows, timber supplies, and other permitted uses.

|

| Camping in July 1938 at the Grout Bay campsite, developed under a mature Jeffrey pine stand that also serves as winter habitat for bald eagles. San Bernardino National Forest, California. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by H.C. Edinborough.) |

Under the Secretary's guidelines, national forest management became the instrument for fitting multiple uses compatibly with each other within the capabilities of forest ecosystems and, over the longer term, adapting the mix and levels of uses to changing market and social values and sustaining national forest resources and their ecosystems for future generations. In 1905, the science underlying U.S. forest and rangeland ecosystems and resource management was still very primitive. The practice of resource management was similarly primitive and, in the absence of strong science, it depended heavily upon learning from past experience, judgment, and such science as was available from European forest conditions and management. As national forest use expanded with rising demands and changing social values, there was enormous room and need for both the science and art to grow and improve. Under these circumstances, adaptive management — adjusting management to fit changing conditions and uses, changing standards, and changing science and art — naturally became the mode for managing the multiple uses. Thus, national forest use and management became as much a learning experience as a management experience. "Breaking New Ground," as Pinchot characterized the Conservation Movement, became an apt way of characterizing the nature of national forest management. And it remains so to this day.

The Organic Act and Secretary Wilson's guidance set the direction for national forest management. That guidance embodied the utilitarian wise-use concept of the Conservation Movement and the fundamental need to protect the biological productivity of resources for their long-term permanence and benefits. Resource use was related to the welfare of local communities and their workers and residents and the direction emphasized that local questions about the each forest's management be resolved at a local level. All uses compatible with resource permanence were to be permitted. Local industry and communities would have first consideration but with as little restriction as possible to minor industries. Sudden changes in local industry conditions were to be avoided in favor of gradual adjustments. Where conflicts occurred, they were to be reconciled in the spirit of "the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run." The 1907 Use Book elaborated this concept. It recognized that national forest uses would "sometimes conflict a little" and had to be "made to fit with one another so that the machine would run smoothly as a whole." Often one use would need to give way a little here and another a little there so that both could benefit "a great deal in the end" (Pinchot 1907).

This became the Forest Service's philosophy for implementing national forest management strategies and practices for the next 55 years, until the passage of the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act (MUSY) of 1960. It defined multiple use as the guiding policy for national forests. The MUSY Act provided for the management of all the various national forest renewable resources in ways that would best meet the needs of the American people — and not necessarily the combination that gave the greatest dollar return or the greatest unit output (USDA Forest Service 1993). The MUSY policy was enacted at a time when strong pressures toward single uses were emerging among several interest groups, especially for timber and wilderness. The policy made the multiple-use purposes explicit and directed that national forests be managed in ways that assured equal consideration for all resource users.

The story of the actual use and management of the national forests and administration by the USDA Forest Service begins in Chapter 2. It covers the early years of national forest management, 1905 to 1945, which are generally referred to as the period of custodial management.

Because the western national forests were largely located in the more remote areas and higher elevations where access was poor and population numbers were low, they generally received a lower intensity of use — including timber harvests, which remained relatively limited and geared to meet local needs until after World War II. Livestock grazing was a singular major exception. As with public domain lands (those lands originally acquired and held by the Federal Government but not reserved for special uses such as the national parks, monuments, and forests or other Federal purposes), national forest rangelands were widely and heavily used for both cattle and sheep grazing almost everywhere in the West.

References

Fedkiw, John. 1989. The Evolving Use and Management of the Nation's Forests, Grasslands, Croplands, and Related Resources: A Technical Document Supporting the 1989 USDA Forest Service RPA Assessment. Gen. Tech. Report RM-175. Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, USDA Forest Service, Fort Collins, CO. 67 pp.

Holmes, Beatrice H. 1972. A History of Federal Water Resource Programs, 1800-1960. Misc. Pub. 1233. Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. 51 pp.

Pinchot, Gifford. 1907. The Use of the National Forests. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Steen, Harold K. 1976. The U.S. Forest Service: A History. University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA. 356 pp.

USDA Forest Service. 1933. A National Plan for American Forestry. U.S. Senate Document No. 12, 73d Congress, 1st Session, with transmitted letter from the Secretary of Agriculture. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. 1,677 pp.

USDA Forest Service. 1993. The Principal Laws Relating to Forest Service Activities. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. 1,163 pp.

Wilkinson, Charles F., and H.M. Anderson. 1985. "Land and Resources Planning in the National Forests." Oregon Law Review 64:1-2. University of Oregon, Eugene. 373 pp.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

FS-628/chap1.htm Last Updated: 20-May-2009 |