|

Managing Multiple Uses on National Forests, 1905-1995 A 90-year Learning Experience and It Isn't Finished Yet |

|

EPILOGUE

A 90-Year Learning Experience — And It Isn't Finished Yet

It is difficult to find a more expressive way to summarize the 90 years of managing national forest multiple uses from 1905 to 1995 than that expressed in the title of the book: "A 90-Year Learning Experience and It Isn't Finished Yet." In 1905, the basic technical knowledge and underlying science of America's forests and forest managers was, at best, extremely limited. There was much to be learned from research, experience, and resource responses to use and management practices. At that time, and in the following decades, management was largely driven by the demand for the use of national forest resources.

Resource use, however, was balanced by an equal on greater concern for protecting the resources from destructive forces — fire, insects, disease, and wind — and for their continued viability and production as natural cover types with a strong emphasis on watershed protection and maintenance of favorable waterflows. The coordination between watershed protection and the management of other resource uses was basic to all national forest management from the beginning, and it remains so to this day. Only the scale of this effort and its methods have changed as uses have expanded and watershed management technology has improved. Watershed protection and maintenance of waterflows have remained the primary and dominant concern of national forest management throughout its first nine decades. Where wildfire or other natural events or shortfalls in use or management caused impairments, early stabilization and rehabilitation were a top priority. Except for the South Fork of the Salmon River event, there have been few, if any, major watershed and waterflow disasters on National Forest System lands.

There have been many changes in management policies and practices. In the early decades, using predator control to help build up big game herds was an accepted and desirable wildlife management practice. In time, however, it became evident in many places that such herds were exceeding their habitat capacity and impairing their own living environments. Thus, a new management principle for reducing or limiting game herds to the capacity of their habitats emerged — a 180-degree shift away from predator control as a primary game management measure.

For many decades, timber harvesting on national forests, particularly clearcutting, was seen as beneficial to elk and other wildlife populations. Clearcuts increased the horizontal diversity of forests, improved wildlife food and forage supplies, and expanded edge effects and related habitats. In the 1960's, however, elk interests observed behavioral disturbances among some of their favorite herds in the Rocky Mountains. They raised questions about the adequacy of the current management direction for elk habitat. Major research studies were undertaken in timbered elk habitat areas over a 15-year period to evaluate timber sale layouts, logging, and road construction with other factors that needed to be taken into account in integrating elk herd habitat requirements with timber management activities. The findings and recommendations from these studies led to a revised elk management strategy.

Selection harvesting was the early recommended silvicultural practice for managing and regenerating old-growth Douglas-fir stands on national forests. But national forest managers, in time, learned that the practice made selectively harvested stands subject to windthrow and timber losses. Thus, they shifted to harvesting and regenerating with clearcuts. In doing so, they also quickly learned that clearcutting was more economically efficient than other silvicultural systems. Over the years, clearcut sizes were reduced to improve the success of natural regeneration and to reduce landscape disturbance. Landscape architects were employed to develop design and location techniques to blend clearcut boundaries into the landscape to simulate natural openings. In the last two decades, alternatives to clearcutting have been increasingly used to reduce the total area clearcut in all forest types.

The idea of setting aside large areas of pristine forest lands as wilderness preserves emerged on national forests in the 1920's, and by the 1950's, 15 million acres were being planned for such designation. Wilderness interests supported this national forest initiative but took issue with the National Forest System's approach to wilderness identification and location when they perceived that it as biased toward maximizing commercial forest area available for timber harvest. These interests influenced Congress to withdraw the Forest Service's authority to designate wilderness in 1964 and to give it to Congress — a step that ultimately led to a relaxation of the pristine standard for national forest wilderness designation. National forest managers, nevertheless, have continued to manage wilderness areas to pristine standards without objection from wilderness interests. During the 1980's, congressional designation of national forest wilderness increased the total area of wilderness to more than 30 million acres — more than double the area that national forest managers had originally planned to designate.

An early policy objective on national forests was the prompt suppression of forest fires. The national forest goal was to reduce the threat of commercial timber losses; the risk of loss of regenerating and immature forests; the threat of damages to soil, streamflows, and community water supplies; and the threat of wildfire to community citizens, residences, property, and other developments.

When it became evident in the 1960's that effective wildfire suppression was contributing to major fuel buildups on many forests, the management objectives shifted to forest fuel and fire management. Under these objectives, where wilderness guidelines prescribed minimum or no human intervention, natural wildfires in wilderness were allowed to burn themselves out naturally. Elsewhere, wildfires were allowed to consume accumulating fuels where the potential damage was limited and expected to be less than the costs of suppressing a wildfire or where a wildfire could accomplish a planned management objective for improving wildlife habitat or some other resource objective.

Prescribed burns were introduced as a management tool to reduce excessive forest fuel loadings that were becoming "difficult-to-control" wildfire hazards and to meet other forest management objectives for wildlife habitat, range improvement, or favorable ground conditions for forest regeneration and growth of forest stands. Today, on certain forests, periodic burns or wildfires are seen as essential in sustaining fire-dependent forest ecosystems.

The 1969 Douglas-fir study examined the feasibility of increasing national forest timber supplies from high-value old-growth Douglas-fir timber stands in the Pacific Northwest. It evaluated different harvest levels and timber management intensities for both the first and second rotations. Unexpectedly, the study found that the current harvests could not be sustained into the next rotation with the current management intensity. This led to a new policy for nondeclining timber harvests. The nondeclining timber harvest policy altered sustainable harvest calculations from a timber inventory plus growth method during the first rotation to the calculated growth potential that the current management would support in the next rotation. The direct implication of this new policy was a need to reduce national forest timber harvests to the level that the current management intensity could sustain into the next rotation. Congress, however, opted to turn this implication inside out and instead raise the intensity of management to a level that would sustain current harvest into the next rotation — a decision that led to major increases in reforestation and timber stand improvement investments. Today, national forest timber management planning determines long-term sustained timber yield capacity for fully managed long-term forest conditions jointly with established management objectives for other multiple uses and existing timber management intensity. The allowable sale quantity is equal to, or more generally less than, the long-term sustained yield because current trend conditions are often less than those for a fully managed future forest.

The rapid growth of wildlife, fishery, recreation, and aesthetic uses on national forests in the 1950's, 1960's, and 1970's greatly increased the need for better national forest planning and management integration and coordination of these uses with commodity production. This rapid growth also expanded the need for specialized expertise and staffing for these resources — a development that steadily and greatly broadened the disciplinary skills and management capabilities on national forests.

Other, more specific, environmental legislation such as the Clean Water, Clean Air, and Endangered Species Acts and other acts passed during the 1970's and 1980's similarly called for new criteria and standards. The Endangered Species Act of 1973, for example, required a stronger emphasis on managing national forests for endangered, threatened, and sensitive animal and plant species — an emphasis that grew rapidly as the list of threatened and endangered species rapidly expanded in the 1980's. The environmental laws also required that Federal land and resource managers inform and involve the public in resource planning and decisionmaking processes.

The National Environmental Policy Act of 1970 (NEPA) and the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA) established new criteria and standards for planning and managing multiple uses on national forests which called for management changes, innovations, and adaptations to ensure higher environmental quality on national forests. This was a massive challenge — national forests constitute almost one-twelfth of the Nation's lands and waters and fully one-eighth of its forests and rangelands. The new science, knowledge, technology, and technical skills required to implement the new criteria and standards were to come much more slowly. The actual implementation of this new management technology, as it becomes available, will come even more slowly because management activities in any one year touch only a small percentage of the 191 million acres of national forest lands and waters.

Public participation in national forest planning and implementation of management projects, on the other hand, expanded very rapidly and led to accelerated appeals and litigation. Such appeals raised issues that led to new National Forest System guidelines on how to inform and involve the public in national forest activities, how to respond to the expanded public's interest and input, and how to reach better decisions — leading to better quality national forest management plans and plan implementation and more effective decisions for managing multiple uses (USDA Forest Service 1981-1992). National forest managers have also worked to develop more effective two-way communication with the public, interest groups, and individuals and more responsive adaptive management decisions. Nevertheless, conflicts among various interest groups about the proper use and management of the national forests have not been eliminated, nor have Federal appropriation and budget limitations on implementing national forest programs.

The Ecosystem Connection

The adoption of the ecosystem approach to national forest management in 1992 expands the need for new science, knowledge, technology, and technical skills, even more — opening the door for a new 90-year learning experience in effectively implementing the ecosystem approach. Its first requirement is that national forest lands, waters, and resources be reclassified according to the national hierarchical framework of ecological units, which in itself will be an important basic learning experience. Fortunately, after two decades of research and analysis, the Forest Service will be ready with the hierarchy of ecoregions and ecosystem units for the United States (USDA Forest Service 1995) and the principles for defining and mapping ecosystem boundaries at their various geographic scales (Bailey 1996). Defining and establishing the boundaries of ecosystem units within national forests is the first, basic step for an effective System-wide approach in managing and sustaining ecosystems, their resources, and their habitats. It will also require new resource inventories reflecting the on-the-ground ecosystem structure and classification — not only for National Forest System lands, but for other ownerships as well. This will take time. It will be several years before a System-wide ecosystem approach can be uniformly and effectively implemented on the ground among the wide variety of ecological units that range in scale from broad ecoregions measured in tens of thousands of square miles, their smaller subregions, landscape zones of similar land types measured in thousands and hundreds of acres, and local land units such as cliff and cave sites, riparian areas, small marshes, and other specific site conditions that are measured by a few hundred to less than ten acres.

Understanding the biological and physical working relationships within ecosystems, the interactions among their subunits, and their response to fitting many uses within them are a new learning challenge as well as a management challenge. Such learning and management is underway in the Pacific Northwest and northern California under the Northwest Forest Plan and the interim strategy (PACFISH) for anadromous fisheries in the Interior Columbia Basin Cooperative Management Project and elsewhere in more local national forest situations. This approach requires managers to consider the effects of use and management on local ecosystem units and their interactions with each other over time within the framework of the structure and functions of the broader ecoregions and landscapes within which the local units occur. Such coordination and integration appear to involve much judgment as well as much uncertainty.

The need to consider resource management and its ecosystem effects on other public and private ownerships adds another complex dimension. The current state-of-the-art (the existing knowledge, science, and experience) of resource management will contribute much to implementing this ecosystem approach, but national forest managers will still need to learn by doing, observing, evaluating, researching, and adapting to changes in ecosystem conditions and new ecosystem knowledge and understanding as they emerge over time.

Adaptive management — the adjustment of management practices to the changing conditions and uses of ecosystems over time — is a corollary of the learning process and will become the path to the future just as it was the path from the beginning of national forest management to the present. National forest management has been and is the fitting of multiple uses into ecosystems according to their capability to support each use, compatibly with existing uses, in ways that sustain ecosystem benefits and their supporting physical and biological resources for future generations. It is necessarily based on the existing state of knowledge and science, management technology, and established policies and values. This has been the underlying goal and nature of national forest management of uses and resources over its history and it remains so today and into the future.

The ecosystem approach to national forest management has always been reflected in the national forests' primary emphasis on protecting and maintaining watersheds and waterflows in the management of all other multiple uses. The wide array of research natural areas, initially established in the 1920's in cooperation with the Ecological Society of America, now represents the tremendous natural heritage and diversity of ecosystems found on National Forest System lands. They reflect a genuine concern for comparing the performance of managed forests with natural ecosystems.

The strong focus on rehabilitating the acquired, badly beaten, and often burned Eastern national forest lands from 1911 to the present has been a deliberate and successful effort to restore the degraded ecosystems they once constituted. The work of Jack Ward Thomas in integrating wildlife habitat management with timber management on four national forests totaling nearly 4 million acres in the Blue Mountains of Oregon and Washington in many ways was an early practical and successful demonstration of the applicability of the ecosystem management principles and approach to National Forest System management (Thomas 1979).

Thus, the concern about ecosystem performance and productivity on national forests is not new. What has changed is the knowledge and science of ecosystem structures and functions and their importance in maintaining the diversity, health, productivity, and sustainability of ecosystems. The enormous growth in the level and diversity of uses and the changing balance among national forest ecosystem uses have also raised questions and even national debates about the quality of the national forest environment for many uses, particularly those associated with recreation activities, wildlife habitats, landscape perspectives, and forest solitude.

Changing public values and the public's concerns about the quality of recreation and wildlife experiences, landscape aesthetics, and wilderness conditions have also contributed to issues being raised by the public about the direction of natural resource management on national forests.

The Endangered Species Act has given top priority to restoring the viability of plant and animal species populations that are officially listed as in danger of or threatened by extinction.

The Clean Water and Clean Air Acts have raised concerns about water and air quality.

The National Environmental Policy Act similarly has elevated the general concern about environmental quality. The National Forest Management Act has raised standards for managing all national forest resources. These changes have largely emerged independently and incrementally. They constitute sharp shifts in resource values and management standards and, in a sense, they have come on the fast track.

The new ecosystem knowledge, science, and management technology to implement these new values and standards have come more slowly. In many ways, their development comes on a slow track. Research for new technology takes time. Training or retraining of thousands of natural resource managers cannot be accomplished overnight. Change in natural resource use on national forests is difficult to bring about without direct commitments from Congress to change the management and production goals as well as the level of appropriations and their balance for national forest use and management. National forests remain resilient and responsive to management. They will respond to new management guidelines and standards that will emerge from new ecosystem management knowledge, science, technology, and learning experiences.

National forest management will likewise respond to growing demands for multiple uses according to the capabilities of ecosystems to produce them. As the learning and management experience continues, national forest ecosystems will also improve in their diversity, health, productivity, and sustainability in some form of dynamic growing stability.

The commitment to an ecosystem approach for managing multiple uses on national forests is a massive one. It is even more challenging than the area of national forests implies because ecosystem management involves consideration of ecosystem conditions beyond the borders of national forests and collaboration with other government land-managing agencies and private landowners as well.

This challenge is not new, but it is more complex. National forest managers from the beginning have been accustomed to coordinating the management of wildlife habitats with State game commissions and wildlife agencies. National forest range management has similarly fitted the needs and management of permittees' rangelands and grazing enterprises with maintaining and improving the range resource. The national forest concern for protecting and maintaining watersheds and waterflows has reflected the water needs and uses, and often the stream conditions, of downstream communities, ownerships, and users. Insect, disease, and wildfire control likewise involved broader ecosystem consideration and coordination than national forests alone because insects, disease, and wildfires are not respecters of ownership or jurisdictional boundaries.

The ecosystem approach calls for a holistic view of the ecological and socioeconomic aspects of entire ecosystem landscapes and their associated rural and urban communities. This is a formidable challenge because the ecological knowledge, its science base, and the management technology for implementing an ecosystem approach holistically on a broad scale over the long term are yet very limited and will develop slowly. Our experience and administrative and political capabilities for integrating management goals and objectives, let alone specific management actions across multiple public land jurisdictions and a multitude of private ownerships, is likewise very limited. We lack established institutional arrangements for doing so.

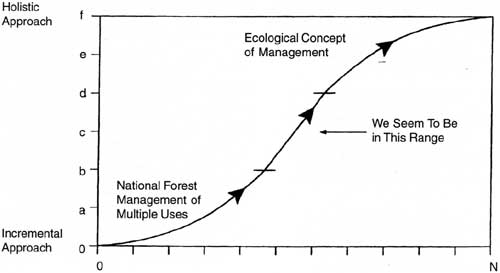

The historical evolution of management of multiple uses on national forests offers strong evidence of an incremental pathway to a holistic ecosystem approach to resource management (fig. 28). We now seem to be about midway along this pathway. The path, however, is very long and will involve considerable learning and long management experience before we arrive at a fully holistic approach to ecosystem management.

|

| Figure 28. The Pathway Hypothesis: over time, the pathway of traditional national forest management leads to a fully holistic approach to resource management. |

The merger of the traditional, largely bottom-up incremental approach of managing multiple uses with the holistic, primarily top-down ecological approach to management will be complex and will develop slowly. Although planning and decision making will become more holistic, implementation will necessarily remain incremental — use by use, area by area, year by year, decade by decade. Management will remain adaptive, requiring much judgment, until we have a credible theory, science, and technology for holistic management that are widely accepted by multiple jurisdictions and multiple ownerships that make up ecosystems.

Thus, implementing the ecosystem approach in managing multiple uses on national forests will continue to be as much a learning experience as national forest management has been in the past. It will move forward adaptively as national forest managers continue to learn from experience as well as adapt to new knowledge and technology and as public goals and objectives for resource management and uses change over time.

References

Bailey, Robert G. 1996. Ecosystem Geography. Springer-Verlag New York, Inc., New York, NY. 204 pp.

Thomas, Jack Ward, ed. 1979. Wildlife Habitats in Managed Forests: The Blue Mountains of Oregon and Washington. Agricultural Handbook No. 553. USDA Forest Service, Washington, DC. 512 pp.

USDA Forest Service. 1981 (1992 Reprint). Public Participation Handbook. Intermountain Region, Ogden, UT. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. 170 pp.

USDA Forest Service. 1995. Description of the Ecoregions of the United States. Compiled by Robert G. Bailey. Second edition, revised and enlarged. Misc. Pub. 1391. USDA Forest Service, Washington, DC. 108 pp.

USDA Forest Service. 1979. Report of the Forest Service for Fiscal Year 1978. Washington, DC.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

FS-628/epilogue.htm Last Updated: 20-May-2009 |