|

NATIONAL FORESTS OF COLORADO |

|

NATIONAL FORESTS

The chief purpose of the national forests is the conservation of wood and water. In this respect all national forests are alike. They are also alike in that all resources—forage, wild life, recreation, and other resources as well as wood and water—are managed with the object of deriving from them the greatest possible contribution to the general public welfare. On the other hand, details of management are different on different forests because of local conditions. On some forests timber growing is all important and takes first place; on some, watershed protection is the big thing; on others, forage is for the time being the resource most necessary to the prosperity of the communities in the region. There is bound to be a great variety of local conditions in 156 national forests scattered in 31 States and 2 Territories.

One of the outstanding features of national-forest administration is decentralization; that is, the placing of responsibility as largely as possible upon the local forest officers. On every forest the local officers plan the administration of their individual units and deal directly with the local problems. Each forest is studied with particular reference to the relation which it bears to the development and maintenance of the industries of the surrounding country, and the aim of administration is to make the resources of the forest serve these industries to the fullest extent.

FIRE PROTECTION

The first requisite for the conservation of forest resources is fire protection. The susceptibility of forests to destruction by fire is a matter of common knowledge. Not a year passes without some loss, and in occasional years, such as 1910, 1919, and 1926, there have been memorable disasters. Without protection little is to be gained by working out and applying advanced methods of forestry. Thus the forester's first job is to keep the woods from burning.

Time is a factor of the highest importance in getting to forest fires and there must be ample provision for transportation and other communication. This means roads, trails, and telephone lines. Equipment for fire fighting must always be on hand and in first-class shape. It must be convenient in case of emergency—and every occasion on which it is to be used is an emergency. Tool caches, therefore, must be located at points where they will be available for cooperative fire fighters and for forest officers. Some of these tool supplies are located at ranger stations, some at camps and mills, and others in red tool boxes which show up conspicuously along the roads and trails.

|

| FIG. 1.—Devils Head Lookout, Pike National Forest F-169495 |

The forests of Colorado owe their preservation from destruction by fire in large measure to the faithfulness and effectiveness with which local residents guard them. Every able-bodied man living in or near the national forests is listed in his most useful capacity in the local cooperative fire-protection organization under a definite agreement with the Forest Service. There are teamsters, truckmen, laborers, timekeepers, and general keymen. The keymen are authorized to hire fire fighters and take initial action in the absence of the ranger. All are paid for their work according to a prearranged scale. By this system a minimum of forest land is left without a responsible and experienced guard and fire fighter. Not only are such volunteer fire fighters ready on call with men, tools, and provisions, but they go promptly to fires they themselves discover. Very often they are the first to arrive at a fire and, where it is small, put it out before the ranger gets to it. In the case of fires which gain too much headway to be put out in a short time, the forest officer, even though he may be away at the beginning, takes charge upon arrival and assumes the responsibility of directing the campaign.

Lightning and man are responsible for all forest fires. About one-fourth are caused by lightning, the rest by man. Lightning fires must always be expected and provision made to combat them. The most effective way to suppress man-caused fires is to prevent them.

Man-caused fires are in almost every case the result of carelessness and are, therefore, usually inexcusable. Accordingly, every effort is made by the Forest Service to educate the public to the need for care with fire in the forest, and to back up this educational work by strict enforcement of the law. Severe penalties are provided by both Federal and State laws for carelessness with all forms of fire on forest lands, and the forest ranger often finds himself in the position not only of fire fighter, but also of policeman, sleuth, and prosecutor. The educational campaign is producing results, and except in occasional dry years the number of fires and the amount of damage are constantly decreasing.

It is of the greatest importance that every tourist as well as every local resident cooperate with the Forest Service in the detection and suppression of forest fires. Whenever an unattended fire is sighted it should, if possible, be promptly and completely suppressed; and if it is too large to be handled, word of the fire should immediately be sent to either the nearest forest officer or the sheriff. It is only by such help from everyone that Colorado's excellent present record in fire prevention will be maintained and improved upon.

FOREST MANAGEMENT

Fire protection, necessary as it is, is not the end in the practice of forestry; and with the best possible protection provided the forester's work is only begun. To manage the forests so as to harvest successive crops of timber with a sustained yield is the ultimate aim of forestry. This work must be based upon a thorough knowledge of the growth habits of the various species of trees and the effect upon them of a large number of factors arising from the conditions in which they grow.

A forest stand often contains, just as a human community does, young, middle-aged, and mature classes. The ideal unit for forest management, called a working circle, must contain these groups whether in one stand of many ages or in a number of separate even aged areas.

|

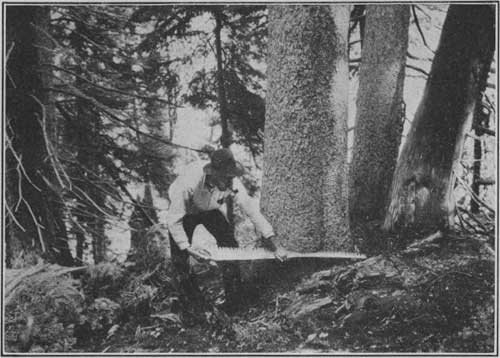

| FIG. 2.—Felling a saw-log tree, Arapaho National Forest F-222413 |

As the individual tree grows from year to year, the total stand increases in volume. Measurements in Colorado forests show this increase to be from 50 to 150 board feet per acre per year. The equivalent of this amount added on the whole unit at this rate may, therefore, be removed annually from the mature age classes in any particular part of the unit without in any way lessening the total volume or disturbing forest conditions essential to watershed protection or forest reproduction. As the work of removing the mature trees progresses from one part of the unit to another, growing space is left which enables the thrifty young trees to graduate into the older classes and eventually be ready for cutting when the cycle again returns, usually after 30 or 40 years.

Timber on the national forests is sold "on the stump." That is, the standing trees must be cut by the purchaser and converted by him into lumber or any other finished product desired. In making timber sales a large amount of supervision on the part of forest officers is necessary in order to assure the proper location of cutting operations and the observance of forestry principles in the course of the logging. The selection of trees to be cut and the consequent regulation of volume and growing conditions are also the responsibility of the forest officer. He marks every live tree to be cut with 'blazes' stamped "U. S." He also supervises through frequent inspection the disposal of slash, regulating the method of disposal primarily from a standpoint of fire protection; and he "scales" or measures the logs, ties, or other special products. In this form the "cut" is charged against the deposits of the purchaser. In Colorado the annual cut on the national forests amounts to about 50,000,000 board feet, or 18 per cent of the annual growth.

RESEARCH

In order to manage a forest properly certain technical information is needed. A forester must know how to cut his mature timber so that the stand will perpetuate itself and so that the remaining trees will maintain their best growth. He wants to know where to find best sources of seed in order to grow nursery stock and how best to grow this stock for planting denuded areas. The answers to these questions are sought through research. Small-scale experiments in cutting, planting, and nursery practice are carried out. Careful detailed records are kept and repeated observations made over a long period of time. Accurate conclusions can then be drawn and applied to larger fields of operation in forest management and planting. It is the function of the experiment stations to carry on this research work and a chain of 11 such stations has been established across the United States, one of which, the Rocky Mountain Forest Experiment Station, is located in Colorado with headquarters in Colorado Springs. In addition to the work done from the stations directly, a great amount of research is done by the administrative force on the national forests under the leadership and general supervision of the experiment stations.

|

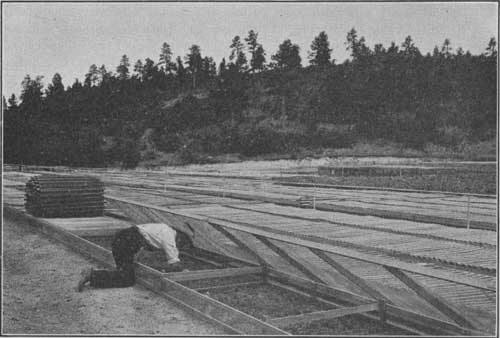

| FIG. 3.—Weeding seedling beds at the Monument Nursery, Pike National Forest F-2000981 |

REFORESTATION

For the purpose of providing for future timber needs and securing immediate watershed protection, lands which have been completely burned over and which are not restocking naturally must be planted with forest trees. Such lands on the national forests of Colorado consist almost entirely of areas burned over so severely many years ago that all trees were destroyed and replaced by a dense growth of grass or weeds. The natural supply of tree seed is very limited in such places and the grass and weeds make conditions very unfavorable for natural reforestation.

Because of the high cost of forest planting it has, so far, been concentrated on accessible locations where there is the most urgent need. Small areas, mostly in the form of experimental plots, are being planted in the national forests throughout Colorado, but for the present the only extensive work is being done on the Pike National Forest.

GRAZING

Grazing is commonly an important use of the western national forests. This is because of the way grazing lands are mixed with timberlands in areas covered by national forests and also because of the large area of surrounding ranch property. Also, surrounding some of the national forests, there are extensive areas of semiarid winter-grazing lands, much of which can be used most efficiently only as they are supplemented with summer grazing in the mountains.

Through the use of range-management plans an effort is made to correlate the grazing uses on the national forests so as to utilize all the forage available, but, at the same time, prevent damage to forest reproduction.

The grazing resources are administered so as to favor the local, small-scale, resident ranch owner, who is the home builder of the region. A preferential system of permits favors such land residents when total ownership both of land and livestock falls within certain maximum limits. Those granted such permits are known as class A. This policy of favoring the local small owner is carried out as far as possible considering the available range, and in harmony with a policy of protecting the investments of the old established users. These older users usually operate on a large scale and are designated as class B. They also have preferences, but are subject to reductions within certain guaranteed limits when it is necessary to accommodate new class A permittees. Such range only as is left over after the needs of these two classes are taken care of is available for speculative stock owners, class C applicants who do not own ranch property. Permits to the latter can be reduced or discontinued by the Forest Service at the end of any annual grazing season. The others are binding for 10-year periods and may be renewed on the same preference basis. The system is designed to promote stability for the individual and the community as well as for the industry.

GAME

The portion of Colorado now included within the national-forest boundaries was once the natural range of deer, elk, mountain sheep, and many other forms of wild life. Although the number is much reduced, game animals are still one of the important assets of this region. They are given consideration accordingly in the administration of the national forests.

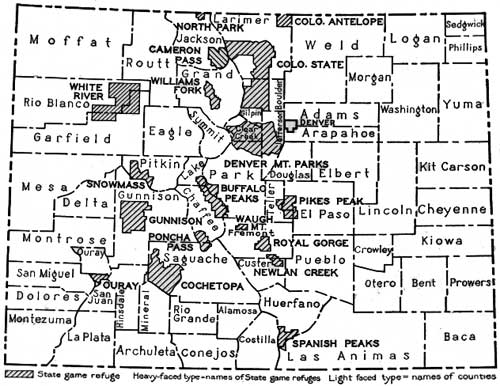

In order to protect breeding herds on limited areas where the naturalist may observe or study them and where a surplus may be constantly produced for the stocking of outside hunting ranges, 17 State game refuges have been established in Colorado, many of them covering portions of the various national forests. To insure the protection for which the refuges were created, the carrying of unsealed firearms in the refuges is prohibited except under special State permit. Outside of these refuges, which are shown on the map (fig. 4), there is no restriction on the carrying of firearms within the national forests, although neither hunting nor fishing is permitted anywhere in the State without a proper license.

|

| FIG. 4.—State game refuges |

RECREATION

An ever increasing number of recreational visitors are finding their way into the national forests. There they find ideal conditions for summer outings, winter sports, and hunting and fishing. Through such use the forests contribute directly to the bone and sinew of the whole country. Furthermore, such use is, in general, in harmony with all the primary aims of forest administration.

Provision is made for free camping, and in many cases through cooperation with local organizations camp grounds are being located and equipped. Where there is any demand, summer home sites are surveyed and offered at a nominal fee to those who want permanent summer quarters in the forests. Under the same arrangement lodges and club houses for organizations may be established. Permits for commercial resorts also are issued where they will help in making the national forests more readily available for human use.

The administration of recreation on these areas requires careful planning. Conflicts with other activities must be avoided and different types of recreation provided for. The hiker needs areas where he will not be offended by the fumes of motor cars, and the itinerant camper must not be prevented from enjoying his gypsying by an excess of private permits. The hunter must have game and the naturalist must have refuges where wild life may be observed and enjoyed unmolested. So this whole activity, perhaps the newest in the national forests, involves much planning on the part of the forest officer.

|

| FIG. 5.—Emerald Lake, San Juan National Forest F-29199-A |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

colorado/sec1.htm Last Updated: 12-Sep-2011 |