|

NATIONAL FORESTS OF COLORADO |

|

FOREST TREES OF COLORADO

In the rugged mountains of Colorado are many thousands of acres of timber, and the responsibility of the Forest Service for its protection and utilization is very heavy. Close under the high peaks is found the Engelmann spruce, gnarled and twisted and stunted by its conflict with mountain storms; for this is the tree frontiersman of the Rocky Mountains, jealously guarding the timber-line march. The fantastic form of these witch trees has made them the quest of many artists and mountain climbers. But more important is the value of these trees in preventing too rapid melting of the spring snows and in protecting the soil on these steep slopes against erosion. A little lower down in the protected valleys and canyons the trees grow tall and straight and are valuable for the production of lumber and other products. Alpine fir is commonly found in these stands. Trees in this Engelmann spruce type are conspicuously lacking in uniformity of size. There is usually a great deal of underbrush, too, so that the type generally has the appearance of a luxuriant tangle, very different from the open, clean stands of western yellow pine or even the lodgepole pine below. Douglas fir grows in mixtures over a wide intermediate range and is very valuable for the making of construction timbers and railroad ties. Lodgepole pine is common in the northern forests of the State, and is easily recognized by its neat stands of uniform, crowded, tall, slender, even-aged trees.

Altogether 12 species of evergreen trees are found in the central Rocky Mountains. Engelmann spruce, alpine fir, western yellow pine, Douglas fir, lodgepole pine, juniper, limber pine, and pinion are the most important commercially. Blue spruce, bristlecone pine, white or silver fir, and the low or scrub juniper, the other coniferous species native to the State, are of less importance commercially.

There are no broad-leaf trees of commercial importance, except the aspen, or "quaking asp," which is used in the manufacture of excelsior and boxes. In addition, this tree, with its light-colored, shiny, trembling leaves and nearly white bark, adds much beauty to the mountain scenery, and is of great importance in the forest because of the readiness with which it, like lodgepole pine, reclaims areas devastated by fire. All of the other broad-leaved trees come only to the foot of the mountains and are restricted to the canyons.

The evergreens all belong to one great family, which is sometimes called the "pine family," and which, as shown by fossils has been in existence since the earliest geological age. Hence, it is not a serious error to call all the evergreens "pines," but it is best to call them conifers, because the habit of bearing the seeds in cones is characteristic of them all. Even the berry of the juniper is a "cone," its segments in most species being completely grown together.

The western yellow pine (Pinus ponderosa) can be distinguished from any other in the region by the fact that its needles are 4 to 6 inches long and occur in bunches of two or three. The needles are coarse, and the limbs are often large, giving the trees a rather heavy appearance. The cones open late in the fall, permitting the seeds to drop out, so that the cones found on the ground are invariably empty. But by pressing on one of the segments or "scales" of the cone one can easily see two large pits where the seed rested until ripe. This tree grows mostly in the lower part of the mountains, where the temperature is warmer. It is seldom seen except on the warm south slopes.

The "versatile" limber pine (Pinus flexilis) is able to grow under so many conditions because of the large size of the seed and the strong seedlings which they produce. It may be distinguished by its light gray bark and by its fine, almost silky needles which almost always occur five to the bundle. The limber pine is a "poor relation" of the eastern white pine and resembles it slightly, but never attains any great size and is of little value except for fuel.

The only tree with which one might confuse limber pine is the bristlecone pine (Pinus aristata), which occurs up toward timber line, and usually on rocky ridges. This tree also has needles in bundles of five, but they are shorter and stiffer than limber-pine needles, and almost always covered with tiny specks of pitch. The cones are prickly, each scale having a sharp hook on its outer extremity, which gives the tree its name. It is also sometimes called "fox-tail" pine, because of the long slender twigs clothed with needles which resemble the brush of the fox.

|

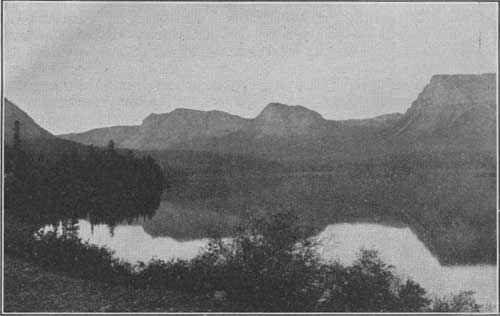

| FIG. 25.—Trappers Lake, white River National Forest F-42975-A |

One tree which occurs very sparingly in the Pikes Peak region, though it is common northward and westward in Colorado and Wyoming, is the lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta), which derives its common name from the long, slender poles formed when the tree grows in thick stands, as it does characteristically. It is distinguished by the yellow-green color of the foliage, by needles 2 to 4 inches long, usually in bundles of two, and by small, hard cones, which cling to the branches for years without opening or dropping their seeds. Sometimes these cones cling so long that they are entirely buried in the wood, and are found mummified when blocks of wood are split open. This ability to retain its cones and seeds is very valuable to the tree when fire occurs in the forest. Though all of the old trees may be killed, the cones are opened by the heat, seeds fall to the ground, and a new forest is started at once.

The piñon of the foothills (Pinus edulis) completes the list of true pines of the region. This is a small, scrubby tree which reaches its northern limit in this region but is very common in the Southwest. It is useful only for fuel and for its seeds or nuts, which are large enough to be an important article of food for the poorer inhabitants of the Southwest and appear on distant markets as a delicacy.2 Unshelled, they are about the size of a Spanish peanut as seen in candy and in the salted state. The cones are small and rough, each cone bearing only a few of these large seeds. The needles of piñon are usually about an inch long.

2It should perhaps be stated that all pine seeds are nourishing and decidedly palatable food. The semihard shells of the seeds, however, have a slightly resinous flavor and must be disposed of if the "meat" is to be enjoyed. The Mexicans who consume many piñon seeds become very adept and are able to feed whole seeds in at one side of the mouth, while a steady stream of empty shells flows out of the other side.

Common companions of the piñon are two or three species of junipers, close relatives of the eastern juniper, which is called "red cedar." The various western junipers3 are difficult to distinguish. Some individuals have decidedly silvery foliage and others are marked by a narrow, cylindrical form as regular as though they had been trimmed with shears. The layman will be satisfied to call them all "junipers." As is well known, the junipers have awl-shaped leaves about one-half inch long, sometimes pressed close to the twigs and under other conditions spreading and making the twigs very prickly. All have berries, some of which require two years to mature.

3Juniperus scopulorum, J. monosperma, and J. utahensis occur in Colorado.

In addition to these is another species which always grows as a prickly low-spreading bush, and is called scrub, or dwarf, juniper.

The spruces are distinguished by needles attached singly on all sides of the twigs, and on close examination will be seen to be four sided and sharp pointed. In the blue spruce (Picea pungens) the needles are if anything a little longer, stiffer, and more "prickly" than in the Engelmann spruce (P. engelmannii), but this is not a certain means of identification, nor does the blue color certainly distinguish the blue spruce from Engelmann's and from Douglas fir, both of which are sometimes very blue. The most certain characteristic of the blue spruce is the length of the cones, which is 3 or 4 inches. But there is another characteristic which is always apparent and is detected at a glance when one becomes accustomed to it. On the main trunk of the blue spruce there are always a number of tiny twigs only a few inches long in addition to and usually between the main whorls of branches. These twigs keep pushing out on the stem for many years, and after the stem becomes large and the twigs die they give it an unkempt, unbrushed appearance. The stem of Engelmann spruce, on the other hand, has none of these adventitious twigs. It is smooth and clean, the bark beginning to peel off at an early age in round thin flakes.

Blue spruce occurs mainly in the bottoms of canyons below 9,000 feet elevation and hardly ever out on the hillsides. Engelmann spruce occurs in the canyons above 8,500 or 9,000 feet. As one goes higher, Engelmann spruce is found making extensive forests on all slopes and aspects up to timber line.

The cones of Engelmann spruce are slightly more than an inch long. These small cones may usually be seen clinging near the extreme tips of the larger trees. In the early summer they are bright red. Engelmann spruce forms the finest timber stands in Colorado, dense forests occurring at high elevations, with individual trees 50 inches in diameter. In spite of having only 60 to 90 days growing season, Engelmann spruce grows faster than any other species. Trees 500 years old are not uncommon.

Throughout the world the true firs are companions of the spruces and are often called "balsams." Alpine fir (Abies lasiocarpa) will be readily distinguished from spruce by its nearly white smooth bark, becoming furrowed (never scaly) only when the stem approaches a foot in diameter. The leaves also instead of being square and pointed are flat and blunt. They tend to turn upward on twigs, so that it appears as though none were attached to the lower Sides of the twigs. If one looks at the end of any twig of a true fir, except when the twigs are growing rapidly in the early spring, he will always find there three blunt, shiny, resin-coated buds.

The white fir (Abies concolor), locally known as silver fir, is much like the alpine fir, except that its foliage is a pale pea green and the needles often 2 inches or more long. It grows at the lower elevations, on hillsides, with western yellow pine and Douglas fir, and in the canyons with blue spruces. Its association with pine and Douglas fir violates all the rules of conduct for well-behaved true firs. The light color of the foliage makes the white fir a beautiful tree, and besides this it usually bears on the uppermost twigs a cluster of large, erect cones, pale green on some trees but more often a deep rich purple. When the cones of a fir ripen the scales fall off, leaving the stalks or, cores of the cones still standing upright and strongly suggestive of Christmas candles in the tops of the trees.

Lastly comes the Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga taxifolia), which is neither fir nor spruce, but possibly a close relation of the hemlocks. Douglas fir is one of the most widespread trees in the Pikes Peak region, and there is evidence that it formerly composed vast and splendid forests in many parts of Colorado and Wyoming, but that these forests have been almost exterminated by fires of by-gone centuries. In many cases lodge-pole pine has taken the place of Douglas fir, but remnants of the fir forests are often found. Douglas fir in the Rocky Mountains, while inferior to its western brother, which reaches such magnificent proportions on the Pacific coast, is nevertheless one of our most valuable trees, its wood being very durable and highly prized for railroad ties and posts.

There are two features of Douglas fir which make it readily distinguishable from all other conifers. At the end of a twig one will always find a single4 cone-shaped, sharp-pointed bud, brownish red in color. On the branches, after the tree is 8 or 10 feet tall, one may almost always find dry cones which are light and papery in texture. Between the smooth, round scales of these cones there project narrower, papery bracts, three-pronged at the tips. No other cones have this feature, which appears to be purely ornamental. When the cones are young (say, until July) the cones themselves are purple, while the three-pronged bracts are green, creating a colorful contrast. Douglas fir occurs generally at middle elevations (8,000 to 9,000 feet) but also at low elevations on cool, northerly aspects.

4Only rarely is there more than one bud.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

|

colorado/sec3.htm Last Updated: 12-Sep-2011 |