|

Shoshone National Forest |

|

Our First National Forest

THE SHOSHONE NATIONAL FOREST was set aside by proclamation President Benjamin Harrison as the Yellowstone Park Timberland Reserve on March 30, 1891. It was the first unit of its kind created after the passage of the Act of March 3, 1891, authorizing the establishment of forest reserves—as national forests were then called—to protect the remaining timber on the public domain from destruction and to insure a regular flow of water in the streams. On the fiftieth anniversary of the establishment of the Shoshone, the national forests embrace approximately 176,000,000 acres of forest land, located in 36 States, Alaska, and Puerto Rico.

The Shoshone National Forest is situated in the heart of the Absaroka Mountains, in northwestern Wyoming. It is bounded on the north by the Montana-Wyoming State line, on the east by the Big Horn Basin, on the south by the Washakie and Teton Forests, and on the west by the Yellowstone National Park. It lies almost entirely within Park County; minor portions extend into Hot Springs and Fremont Counties.

This national forest is the largest of 21 in the Central Rocky Mountain Region, including within its boundaries 1,592,428 acres, of which all but 26,104 are Federal land. The forest is about 75,000 acres larger than the State of Delaware. Elevations within the forest range from 4,600 to 13,140 feet, thus providing a wide variation in climate, vegetation, and wildlife. At the lower elevations the summers are warm and the winters mild. The higher mountains enjoy only a brief cool summer and are snowclad most of the year.

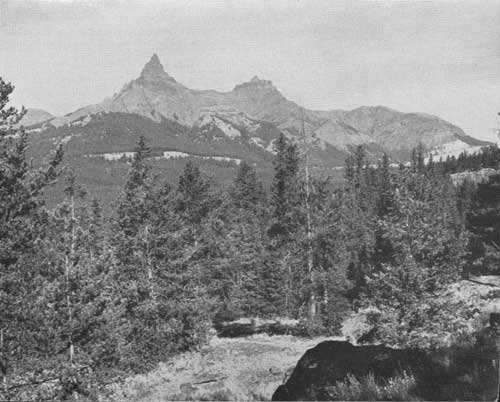

Few mountainous sections are more rugged or spectacular. Geologically the formations are new, and immense areas of exposed rock are broken by and interspersed with mountain meadows and mantles of unbroken forests. Those who have packed into the back country, or have driven through the North Fork of the Shoshone River Canyon, or over the Beartooth Plateau agree that the variety of scenery and vegetative types is superlative.

|

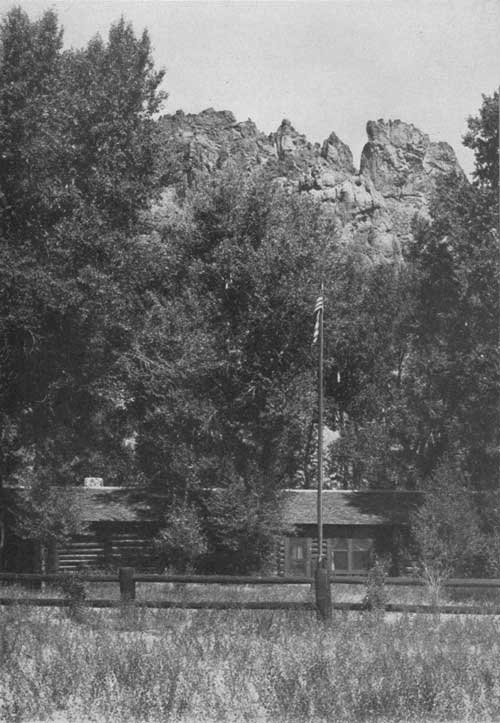

| Wapiti Ranger Station—the oldest in existence. F—385973 |

ADMINISTRATION FOR PUBLIC USE

In the administration of national forests the aim is to manage them in such a way as to make their resources of largest service to the local communities, the State, and the Nation. This is accomplished by promoting the highest social and economic uses of the forests consistent with the proper use of lands. Such an objective is definitely pointed toward the maximum sustained yield from all resources.

The national forests are under the administration of the Forest Service, U. S. Department of Agriculture. Each forest is under the charge of a forest supervisor. Headquarters of the Shoshone is in Cody, Wyo. Every forest is divided into districts, each of which is under the supervision of a district ranger, who has control of all its activities. His responsibilities include protection of the resources against fire and other enemies, the supervision of timber sales, and the grazing of large numbers of cattle, sheep, and horses; the management of wildlife resources; looking after different permitted uses, such as pastures, summer homes, resorts, power developments; maintaining forest improvements, including ranger station buildings, lookout stations, telephone lines, roads, trails, and range improvements; and providing protection and furnishing information to the thousands of people who come every year to enjoy vacations in the forest.

The Shoshone National Forest is divided into four ranger districts, as follows: The Clarks Fork, the Wapiti, the South Fork, and Greybull. The Greybull is the smallest ranger district, with approximately 300,000 acres. The Clarks Fork is the largest, with about 529,000 acres under the jurisdiction of the district ranger.

HIGHLIGHTS OF EARLY HISTORY

Perhaps nothing contributes more to the real enjoyment and to the fascination of a forest than a knowledge of its early history. Many events within this area played an important part in the growth and development of northwestern Wyoming. Many of these are nearly forgotten, and others are not generally known.

The earliest inhabitants of the forest are believed to have been Indians known as the "Sheepeaters." Just who the "Sheepeaters" were is not definitely known. Some historians claim they were an unintellectual branch of the Snake tribe, others insist that they were renegades and misfits, driven out of the plains tribes, the Crows, Blackfeet, and Shoshones, who were forced to the timberclad hills where rough topography and cover permitted them to evade capture and killing at the hands of their erstwhile tribal members. They lived in crude tepees constructed entirely of poles. The "Sheepeaters" derived their name from the fact that they preyed extensively on mountain sheep and to some extent on other species of big game. They trapped their prey in pens or corrals made of stone.

The first white men entered Wyoming more than 30 years before the American Revolution. In 1743, Francois and Louis De La Verendrye, French-Canadian brothers, traveled through the Rocky Mountain region to establish branch trading posts. Their home and main post was in the Great Lakes region. They entered the Big Horn Valley from the north and traveled up Wood River in the southern part of the forest and crossed the rugged Continental Divide near the Washakie Needles on their way into the Wind River country.

|

| A section of the rugged Beartooth Plateau as seen from the Red Lodge-Cooke City Highway. F—308547 |

Years later, in 1807, John Colter, who startled the world with his fantastic and unbelievable stories of the natural wonders in Yellowstone Park, traveled up the Clarks Fork River, after leaving the Lewis and Clark Expedition on the Missouri. Colter's exact routes of travel are hotly disputed by historians, but it is well established that he was the first white man to see the "Stinking Water" River (the Shoshone), so named by him because of the foul odors from mineral hot springs along its banks.

The trail along the Clarks Fork followed by Colter was for generations a transmountain route of Indian tribes living west of the Continental Divide which led to the great buffalo country to the east. Among the tribes using this trail were the Bannocks and Lemhi. After hunting among the herds in the Big Horn Basin and on the plains east of the Big Horn Mountains, they returned to their homes heavily laden with meat and hides. These expeditions frequently led to fiercely fought battles with the Shoshones and Crows, whose territories were being invaded.

The De La Verendryes and Colter were followed by other "mountain men," equally venturesome, representing the American and Rocky Mountain fur companies and smaller independent concerns. These hardy, restless, rugged individuals, including such men as Lisa, Sublette Brothers, Fraeb, Gervais, and Bridger, were actually the first settlers in what is now the State of Wyoming, notwithstanding the common belief that the first settlements in the Territory were in the eastern and southern parts. These pioneers exploited the country, trapping fur-bearing animals and trading with the Indians for their take in the pelts.

|

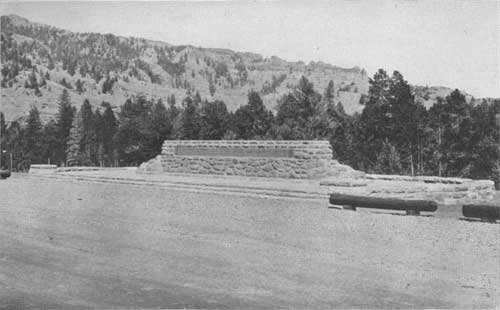

| Pilot and Index Peaks, within the North Absaroka Wilderness Area. F—385841 |

Following them came the nomadic prospectors and miners, and after the miners came the first really permanent residents, the cattlemen. The establishment of the first stockyards in Kansas City, in 1870, gave impetus to the expansion of cattle-raising in the West. From 1870 to the 1890's, this industry grew with unprecedented speed. Charles Carter, in 1879, trailed in from Oregon the first herd of cattle brought into the Big Horn Basin. Later came Capt. Henry Belknap, Otto Franc, Col. W. D. Pickett, and J. M. Carey, all of whom shaped ranches out of virgin territory on the west side of the Big Horn Basin, immediately adjacent to the mountain slopes now inside the forest.

From the early eighties the herds increased, and more and more cattle came into the Big Horn Basin. Homesteaders and settlers were "squatting" on and taking up large acreages of the best range land, and finally, there was not enough year-long range for the increased number of livestock. The advent of the farmer forced drastic changes in livestock operations. Stockmen were obliged to produce forage crops to carry a part of their herds through the winter. Eventually it was necessary to increase the production of forage crops on the land under cultivation, and this led to the development of irrigation projects, first by the ranchers, and then by the Federal Government. With water for their lands and constantly improving transportation facilities, farmers were able to produce such cash crops as small grain, truck crops, sugar beets, potatoes, and peas.

As this country was further developed and became more heavily populated, stockmen grazed their livestock in the higher foothills and eventually in the mountains during summer, depending upon the Big Horn Basin, which had formerly been used year-long, for winter range. Thus began the first actual dependence of the community upon territory within the forest. As irrigation projects developed, the second—and now perhaps the most important—great economic value of the rugged mountains in the forest became apparent in their capacity to conserve and store water for summer use in the valleys below.

The Federal Government recognized the importance of placing the great mountain wilderness of the West under control, to assure the perpetuity and proper use of the natural resources. The establishment of the Shoshone Forest in 1891 was the first step taken in carrying out this comprehensive program. The preservation of the natural resources is now assured, not by the elimination of use of the forage, timber, water, and other resources of the forest, but rather by the use of all under proper and progressive management.

|

| The Blackwater Firefighters Memorial. F—386010 |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

handbooks/shoshone/sec1.htm Last Updated: 19-Nov-2010 |