|

Forests and National Prosperity A Reappraisal of the Forest Situation in the United States |

|

THE TIMBER RESOURCE

Timber Is a Crop

When white men began to settle this country the timber stand probably amounted to at least 8,000 billion board feet. This enormous volume was very largely in virgin timber, centuries old. Now we have about 1,600 billion board feet, only about half virgin. In the course of 300 years, and chiefly during the last century, we have used or destroyed most of our original timber heritage plus much of what has grown in the meantime. The time is long past when timber could safely be viewed as a reserve to be drawn upon without regard for replacement. It must now be regarded as a crop.

The timber crop must be harvested in trees of a size and quality suitable for commercial use; [6] and since about 80 percent of all timber products are cut from trees of saw-timber size, it is important to think of the timber crop primarily in terms of saw timber. [7]

To maintain an annual crop of merchantable timber, there must be a succession of age classes from seedlings up to full-grown timber so that as merchantable trees are cut each year new ones will be ready to take their places. If the age classes were properly balanced and the amount cut each year were equal to the annual growth, the volume of standing timber would remain constant. It could then be viewed as growing stock or forest capital on which the annual crop accrues as interest. In this light, until the productive capacity of the land is reached, the more growing stock or standing timber there is, the greater the crop available for cutting each year.

This does not apply strictly to virgin forests, because in them death and decay usually offset current growth. They do not fully meet the growing-stock concept until they have been converted to a net growing condition by removal of overmature trees.

The Timber Stand

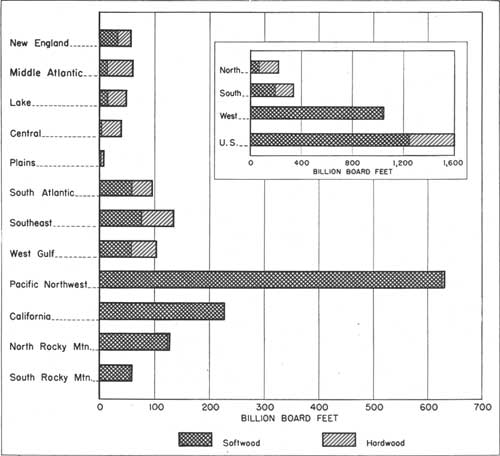

As of the beginning of 1945, the stand of saw timber was estimated at 1,601 billion board feet (table 4 and fig. 3). The volume of all timber 5 inches or more in diameter breast high was 470 billion cubic feet. These are large figures. But critical examination shows that growing stock or forest capital is by no means satisfactory.

|

| FIGURE 3.—Saw-timber stand in the United States, by region, 1945. (click on image for a PDF version) |

TABLE 4.—Timber volume, United States, 1945

| Section and region |

Saw timber1 |

All timber2 | ||||

| Total | Softwood | Hardwood | Total | Softwood | Hardwood | |

| Billion bd ft. |

Billion bd ft. |

Billion bd ft. |

Billion cu. ft. |

Billion cu. ft. |

Billion cu. ft. | |

| North: | ||||||

| New England | 58 | 33 | 25 | 25 | 12 | 13 |

| Middle Atlantic | 62 | 14 | 48 | 27 | 5 | 22 |

| Lake | 50 | 15 | 35 | 23 | 7 | 16 |

| Central | 44 | 3 | 41 | 21 | 1 | 20 |

| Plains | 6 | 1 | 5 | 4 | (3) | 4 |

| Total | 220 | 66 | 154 | 100 | 25 | 75 |

| South: | ||||||

| South Atlantic | 97 | 59 | 38 | 36 | 17 | 19 |

| Southeast | 136 | 77 | 59 | 54 | 24 | 30 |

| West Gulf | 105 | 58 | 47 | 41 | 18 | 23 |

| Total | 338 | 194 | 144 | 131 | 59 | 72 |

| West: | ||||||

| Pacific Northwest: | ||||||

| Douglas-fir subregion | 505 | 501 | 4 | 117 | 115 | 2 |

| Pine subregion | 126 | 126 | (3) | 29 | 29 | (3) |

| Total | 631 | 627 | 4 | 146 | 144 | 2 |

| California | 228 | 228 | --- | 45 | 45 | --- |

| North Rocky Mtn. | 127 | 126 | 1 | 33 | 33 | (3) |

| South Rocky Mtn. | 57 | 56 | 1 | 15 | 14 | 1 |

| Total | 1,043 | 1,037 | 6 | 239 | 236 | 3 |

| United States | 1,601 | 1,297 | 304 | 470 | 320 | 150 |

1"Saw timber" includes merchantable

trees large enough to yield logs for lumber, whether or not they are

used for this purpose. Because the minimum size of logs acceptable for

lumber varies, the minimum size of saw-timber trees ranges from 9 to 23

inches d.b.h., depending upon the species and region.

2"All timber" includes trees 5 inches and larger in

diameter breast high.

3Less than 0.5 billion.

| ||||||

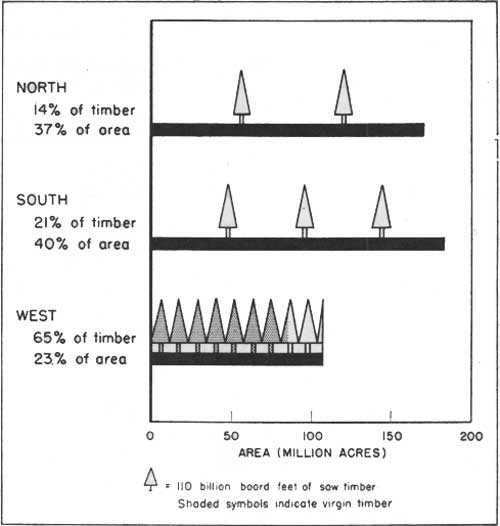

For one thing, growing stock east of the Great Plains is badly depleted. The land is generally understocked. Although three-fourths of the commercial forest land is in the East, the timber there—558 billion board feet—is little more than one-third of the national total (fig. 4). Largely second growth, it is generally of poorer quality than the virgin timber. Saw-timber stands in the North average only 3.8 thousand board feet per acre and in the South 3.3 thousand.

|

| FIGURE 4.—Distribution of the saw timber, United States, 1945. |

On the other hand, two western regions—the Pacific Northwest and California—with less than one-seventh of the commercial forest land, have more than half the saw timber in the United States. In the Douglas-fir subregion the saw timber averages 38 thousand board feet per acre. Such heavy stands are also characteristic of the redwood belt in California.

Almost 80 percent of the 1,043 billion board feet of saw timber in the West is in virgin stands. If these stands are cut so as to put them in good growing condition, the average volume needed as growing stock for future crops will generally be less than at present. Nevertheless, this backlog of forest capital is an extremely important part of our timber supply and should be carefully husbanded.

The occurrence of different species in different parts of the country is another basic element in the situation. Timber in the West is almost all softwood, the kind that is in greatest demand for the major industrial uses. But in the North about three-fourths is hardwood. Maine is the only northern State with more softwood than hardwood. Even in the South 43 percent of the saw timber is hardwood.

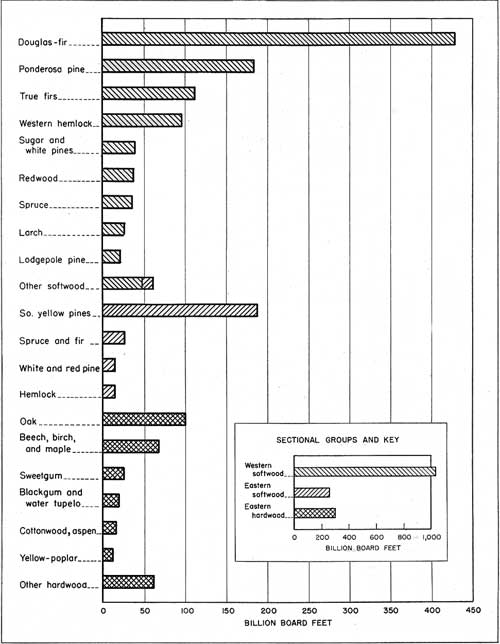

Half the saw timber in the United States is of three species (fig. 5):

| Species: | Billion bd. ft. |

| Douglas-fir | 430.0 |

| Southern yellow pine1 | 188.3 |

| Ponderosa pine | 185.4 |

| 803.7 | |

| 1All commercial southern pine species grouped together. | |

|

| FIGURE 5.—Saw-timber volume, by kind of wood, United States, 1945. (click on image for a PDF version) |

There is now only 15 billion board feet of white and red pine, species that once were foremost in our lumber markets.

Oak is the leading hardwood, with 101 billion board feet, about equally divided between North and South. This is one-third of all the hardwoods. Birch, beech, and maple, as a group, come next with 68 billion board feet, mostly in the North. [8]

A most disturbing fact is that the forest growing stock continues to decline. The 1945 estimate of 1,601 billion board feet of saw timber is 43 percent less than reported by the Bureau of Corporations (Department of Commerce) for 1909, and 9 percent less than the Forest Service estimate for 1938. [9]

Although the 1938 and 1945 figures are not entirely comparable, [10] the fact of a major decline in saw-timber volume in recent years is clinched by figures for the regions where comparable data are available from the Forest Survey (table 5). The saw timber in 15 surveyed States dropped 156 billion board feet or 14 percent between the time of original survey and 1945—an average period of 11 years. These States contain 60 percent of the saw timber in the United States and account for about three-fourths of the annual cut.

TABLE 5.—Decrease of saw-timber stand between original survey and 1945

| Region | Years of original survey |

Decrease | |

| Billion bd. ft. | Percent | ||

| Lake | 1934-36 | 6.9 | 12 |

| South Atlantic (N. C. and S. C. only) | 1936-38 | 1.6 | 2 |

| Southeast1 | 1932-36 | 22.0 | 15 |

| West Gulf2 | 1934-36 | 13.0 | 12 |

| Pacific Northwest3 | 1933-36 | 112.3 | 15 |

| 15 States | 1932-384 | 155.8 | 14 |

1Tennessee not included.

2Northwestern Arkansas and northeastern

Oklahoma not included.

3Volumes in original survey adjusted for subsequent

shifts between commercial and noncommercial status.

4Median year, 1934.

| |||

Ownership of the Timber

Ownership is an important aspect of the timber situation because rate of cutting and measures taken to insure desirable new growth are related to the intent of the timber owner, and the stability of his tenure.

Up to the close of the last century the policy of this country was to turn the public domain over to private ownership in order to promote settlement and development. Not until practically all the land east of the Great Plains and much of the best and most accessible land of the West had passed into private ownership did concern for future timber supply lead to the setting aside of the national forests and a basic change in our policy of land disposal.

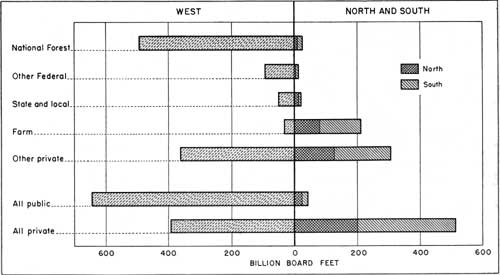

As a result of rapid exploitation of private timber and of a conservative policy in opening up the national forests—both related to economic circumstances—43 percent of the saw timber now stands on the 25 percent of the commercial forest land that is publicly owned (table 6 and fig. 6).

|

| FIGURE 6.—Ownership of saw timber in the United States, 1945. (click on image for a PDF version) |

TABLE 6.—Ownership of saw timber, 1945

| Ownership class | North | South | West | United States | |

| Public: | Billion bd. ft. |

Billion bd. ft. |

Billion bd. ft. |

Billion bd. ft. | |

| National forest | 8 | 14 | 496 | 518 | |

| Other Federal | 2 | 4 | 98 | 104 | |

| State and local | 10 | 3 | 52 | 65 | |

| Total | 20 | 21 | 646 | 687 | |

| Private: | |||||

| Farm | 76 | 134 | 34 | 244 | |

| Other private | 124 | 183 | 363 | 670 | |

| Total | 200 | 317 | 397 | 914 | |

| All owners | 220 | 338 | 1,043 | 1,601 | |

The proportion differs greatly between East and West. In the West almost one-half is in the national forests and 15 percent is in other public ownership; less than 40 percent is in private ownership. But the 397 billion board feet of western private timber, mostly in the Pacific Northwest and California, is generally more accessible and of better quality than the public timber.

In the East, although the acreage in public ownership has been increased as a result of inability of private owners to hold and restore cut-over lands or of their willingness to sell, 93 percent of the saw-timber volume is privately owned. Clearly, public forests in the East are not able to make a very large contribution to national timber needs.

More than one-fourth of the private timber is on the farms. In the Central, Plains, and South Atlantic regions, farms contain more timber than do other private holdings. But in the Douglas-fir subregion of the Pacific Northwest, farms have only 4 percent of the private timber because most of the forest land on the farms is cut-over. The farm timber resources, especially in the East, contribute a good deal to the national timber supply. Properly managed, they can also be a more stable and better source of farm income.

Private timber in other than farm holdings is the major source of raw material for the timber industries at present. How much of the 670 billion board feet in this class of ownership is held by the industries themselves and how much is in the hands of other types of owners is not known. However, the lumber and pulp companies own only 15 percent of the private commercial forest land. Quite plainly, good management of the industrial timber holdings, although essential, will not of itself provide an adequate supply of timber products for the Nation.

Growth Classes Not Well Balanced

It is not enough to appraise forest growing stock in terms of its volume. The distribution of age classes and the quality are also important. Although age or growth classes should be balanced locally, it is only possible here to bring out major features of the situation for the North, South, and West (table 7). [11]

TABLE 7.—Distribution of growth classes, in percent of commercial forest acreage, 1945

| Class of area | North | South | West | United States |

| Saw-timber: | Percent | Percent | Percent | Percent |

| Virgin | 1.3 | 0.5 | 38.5 | 9.7 |

| Second growth | 27.0 | 53.2 | 16.0 | 34.8 |

| Total | 28.3 | 53.7 | 54.5 | 44.5 |

| Pole-timber | 24.3 | 16.0 | 22.6 | 20.6 |

| Seedling and sapling | 29.0 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 18.6 |

| Poorly stocked seedling and sapling, and denuded | 18.4 | 17.8 | 10.5 | 16.3 |

| All areas | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

In the North almost half the commercial forest land bears only seedlings and saplings [12] or is denuded. Another one-fourth is in pole timber too small for sawlogs. Only 28 percent of the land bears stands of saw-timber size. A survey in New England showed that in 69 out of 118 mills, cutting primarily softwoods, the average log size was 10 inches or less. One may drive for miles through forest land in some parts of the North without seeing any merchantable saw timber.

In the South more than half the commercial forest land has been classified as saw timber; however, stands with only 600 board feet per acre qualified as saw timber, in contrast with 2,000 board feet in most other eastern regions. Large saw timber is scarce in the South; stands with more than half the saw-timber trees over 18 inches in diameter occupy only 1 percent of the forest land. In the West Gulf and Southeast regions the average pine saw-timber tree is about 20 percent smaller than 10 years ago. An increasing number of mills are cutting 6-inch trees and it is not uncommon to see a logging truck carrying 50 or more logs. Obviously, mills operate on such small logs only because the supply of larger timber is scarce. In the Mississippi Delta many hardwood mills are operating on logs one-half or one-third as large as formerly and most of the rest face a similar decline in the near future.

In both North and South the keen demand for pulpwood, mine timbers, box-grade lumber, and other items which can be cut from small trees induces premature cutting of young trees which should be left to grow. This tends to perpetuate and aggravate the present shortage of larger timber.

In the West as a whole, virgin stands now occupy less than two-fifths of the commercial forest land, and one-fourth has been reduced to seedling and sapling growth or is denuded. Taking the Douglas-fir subregion of the Pacific Northwest alone, the latter proportion is even greater.

The 44.6 million acres of virgin forest contain more than half our saw-timber volume. But only one-fourth of this acreage meets the high standards popularly associated with virgin timber: heavy stands of large, high-quality trees of good species with little defect (table 8). The best of the virgin timber is in the Pacific Northwest. In California and the Rocky Mountain regions, which have half the acreage, half of it is rated as poor quality. For the country as a whole, 37 percent of the virgin forest is of poor quality. These poor-quality stands, containing only 15 percent of the total volume of virgin timber, are often very defective and of doubtful value. Some are long past their prime. Others contain a high percentage of inferior species; and others, now merchantable, are on poor sites which, as a practical matter, may never again grow good timber.

TABLE 8.—Quality of virgin timber stands

| Region or section | Area | Stand quality | ||

| Good | Medium | Poor | ||

| Million acres |

Percent | Percent | Percent | |

| Pacific Northwest | 18.5 | 39 | 40 | 21 |

| California and the Rocky Mountain regions | 22.8 | 12 | 36 | 52 |

| North | 2.3 | 19 | 54 | 27 |

| South | 1.0 | 55 | 34 | 11 |

| United States | 44.6 | 25 | 38 | 37 |

Much of the Forest Land Is Poorly Stocked

Another indication that growing stock is below par is the prevalence of poor stocking—about 35 percent of all the commercial forest land is deforested or has less than 40 percent of the number of trees required for full stocking:

| Poorly stocked and denuded forest land | ||

| Section: | Million acres |

Percent of commercial forest area |

| North | 59.4 | 35 |

| South | 85.2 | 46 |

| West | 19.2 | 18 |

| United States | 163.8 | 35 |

This includes 58.0 million acres of second-growth saw timber; 30.5 million pole timber; and 75.3 million of seedlings, saplings, and denuded areas.

Almost nine-tenths of the poorly stocked stands are in the North and South. The southern forests are the most deficient, almost half being deforested or poorly stocked. In both North and South 35 to 40 percent of the second-growth saw timber and pole timber is poorly stocked and not over 25 percent is more than 70 percent stocked.

Of special significance is the 75.3 million acres of poorly stocked seedlings and saplings and wholly denuded lands. This idle forest land—representing about 1 acre in every 6—contributes little to the support of roads, schools, or other community services. It supports no jobs. Taxes, if paid, must come from other productive enterprise.

By and large, the rehabilitation of denuded forest land is a job that must be done by the public or with public aid if it is to be done. Yet 61.8 million acres or 82 percent of this idle land is in private ownership, as shown in the accompanying tabulation. Almost nine-tenths of this is in the East.

| Forest land | |||

| Ownership: | All commercial (million acres) |

Denuded1 | |

| (million acres) | (percent) | ||

| Federal | 89 | 7.1 | 8 |

| State and local government | 27 | 6.4 | 24 |

| Private | 345 | 61.8 | 18 |

| All owners | 461 | 75.3 | 16 |

| 1Includes poorly stocked seedling and sapling areas. | |||

Only 8 percent of the commercial forest land in Federal ownership is denuded, or nearly so, in contrast to 24 percent for the forests held by State and local governments and 18 percent for the private lands. The Federal percent is low because these forests, largely in the West, have been protected for many years, and cutting on them has been generally good. The high percent for State and local public forests reflects the denuded condition in which so much of this land in the East came into public ownership, often through tax delinquency.

It is reasonable to assume that the acreage of poorly stocked land will shrink as a result of improved fire protection and better cutting practices. Indeed, surveys in the South indicate that stocking in that region is better now than it was a decade ago. Young growth is springing up on millions of acres now protected from fire. This is one of the hopeful signs.

Quality of Timber Is Declining

Exploitation of the forests has lowered timber values in a number of ways. "High-grading"—cutting the best trees and leaving the poor—destructive cutting, and fire have all replaced valuable timber with inferior stands.

Evidence from all regions makes it clear that the fine logs needed by many forest industries are no longer abundant. This is serious because only after a long period of purposeful management can second growth approach the high quality of the original timber.

In the Northwest, the young and rapidly expanding Douglas-fir plywood industry faces major readjustment almost before it has hit its full stride. In the South, veneer manufacturers have difficulty maintaining an adequate flow of suitable hardwood logs. Some piece out their supply with logs from South America.

White oak suitable for tight cooperage is playing out also. Some operators are going after as few as 10 trees per 40 acres.

So it is with other items. The end of Port Orford cedar for battery separators is in sight. The cedar-pole industry faces radical curtailment. Hickory ski blanks are hard to get. Durable heart cypress in any quantity will soon be a thing of the past.

High-grading, as to both species and quality, began in Colonial days with the combing of the eastern seaboard for white pine masts and oak ship timbers. It went through another cycle as the country's growing lumber industry took the virgin white pine in the Middle Atlantic and New England States, leaving spruce and hardwoods for a later generation.

Before the pulp and paper industry became an important factor, lumbermen had again worked over the northeastern forests, selecting the big spruce that could be logged to the drivable streams. Pulp operations, in turn, have been concentrated on the remaining spruce and balsam fir, practically eliminating these species from some of the mixed stands and leaving much of the land in possession of hardwoods, which are often unmerchantable and highly defective.

Even where the northern hardwoods could be marketed, operators sought out the best yellow birch for veneers and sugar maple for flooring. furniture, etc. Beech, although an important species, has been largely neglected, not only because the wood is more difficult to season, but also because the trees are so commonly defective.

In southern New England the deterioration of the sprout hardwood forest by repeated cutting and fire (accentuated by the blight which killed all the chestnut some 25 to 30 years ago) has left little timber attractive to the timber industries. In fact, forest management here is handicapped by the difficulty of disposing of the inferior growth that now preempts so much of the land.

In the Middle Atlantic region between 5 and 6 million acres that once bore good commercial stands have been hit particularly hard. Destructive logging and repeated burning have almost desolated much of the oak-pine land of New Jersey. Similar practices in eastern Pennsylvania converted a large acreage of good forest to scrub oak. Under organized protection some of this land is slowly recovering, but the composition and quality of the new forest are distinctly inferior to what might have been maintained, as is shown by isolated tracts that escape destruction.

In the Lake region forest deterioration is an old story. It has perhaps been more complete and more extensive than in any other region and it is still continuing. Farm woodlands in the oak-hickory sections are mostly stocked with short, limby, and defective trees. Farther north, 5 million acres which once bore magnificent pines now grow scrubby aspen—scrubby because on that dry, sandy soil aspen grows slowly and deteriorates at an early age. This scrubby and often worthless timber greatly impedes the growth of conifer plantations. As for saw timber, since 1936 the volume of white pine and red pine has dropped 29 percent; birch, beech, and maple together have declined 16 percent; but the volume of the much less desirable aspen increased 55 percent.

During the war, Missouri produced only about 32 million board feet of softwood lumber a year. Yet in 1899 its softwood output was 273 million board feet. Although from 250 to 300 million board feet of hardwood lumber is still cut in the State, the forests of the Ozarks have largely degenerated into a stand of small and inferior timber that can support little industry. A recent study indicated that two-thirds of the trees 5 inches and larger in diameter were defective.

Throughout the South from Virginia to Texas the story is much the same, though the details vary. In the Appalachian Mountains, the lumber industry has concentrated on yellow-poplar and the better oaks. Removal of such timber from the coves in many instances reduced the remaining forest to an unmerchantable condition from which it has been slow to recover. Longleaf pine has been succeeded by scrub oak on over 2 million acres, mostly in Florida. The inferior hackberry-elm-ash type has replaced more valuable oak and sweetgum in from 10 to 15 percent of the delta and bottom land of the Mississippi.

In mixed pine-hardwood stands of the South, heavy cutting, which took pine to a much smaller diameter than hardwood, has allowed hardwoods of increasingly inferior quality to take over. For example, entire counties in the Piedmont of North Carolina are now covered with small or low-grade hardwood, because the mills have virtually exhausted the pine timber and better hardwoods. The total cubic-foot volume of softwood timber in the Southeast and West Gulf regions decreased 4 percent from the early thirties until 1945, whereas the hardwood volume increased 5 percent (fig. 7). In this case the combined cubic-foot volume remained practically unchanged, yet the forest was by no means holding its own. Hardwood saw timber declined almost as fast as the pine.

FIGURE 7.—Southern pine volume declines while hardwoods gain. Data refer to total volume of all trees 5 inches and larger in 32 survey units containing 82 percent of all timber in the West Gulf and Southeast regions.In the North Rocky Mountain region, particularly in the panhandle of Idaho, western white pine has been the mainstay of the lumber industry. The western hemlock and white fir with which the pine is associated have been largely without a market. Commonly defective, these species left after high-grading for white pine often preclude the reestablishment of a satisfactory pine forest. In other Rocky Mountain types ponderosa pine has been cut, while Douglas-fir (of secondary value in the interior regions) has been left.

Similarly the lumber industry in California has been built around redwood, sugar pine, and ponderosa pine. These species make up less than half the stand, but supply more than 70 percent of the region's cut. Removal of these species, especially in the mixed type of the west side of the Sierras, often leaves a forest in which the less desirable white fir and incense-cedar predominate.

Some of the Timber Is Not Operable

Although much timber not now merchantable may find a market as forest depletion and timber shortage become more acute, we cannot count on using all the timber included in the inventory. There will always be some timber beyond the economic pale. The volume may be less in periods of especially strong demand; and it may be more in periods of depression. It will not always be the same trees, or in the same stands.

Some inoperable timber lies in localities that have already been reached by commercial operations. This is inoperable in a more permanent sense than the timber in parts of the West that have not yet been opened up. Some of it is inoperable because it is so defective, scattered, in such small blocks, or in such difficult locations that it may never be economically feasible to get it out. For instance, 100 billion board feet of saw timber occurs in stands too light to justify commercial operation. The poor quality of some of the virgin stands has already been mentioned. Small size and limited utility of certain species may also keep some timber beyond economic access. In mixed stands, moreover, trees of inferior species or poor quality are often lost if they cannot be marketed along with the better trees.

Although the aggregate effect of these factors cannot be dependably estimated, it is important to make allowance for economic unavailability in calculating allowable cut or establishing growth goals.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

misc-668/sec3.htm Last Updated: 17-Mar-2010 |