|

Forests and National Prosperity A Reappraisal of the Forest Situation in the United States |

|

HOW TIMBERLANDS ARE BEING MANAGED

The United States has been slow in facing up to the hard fact that to produce timber in ample, sustained quantities requires purposeful management—real forestry.

The job to be done is not so much one of establishing new forests (although this, too, has its place) as it is of properly treating and utilizing those we have. A great deal depends on timber-cutting practices; on whether the amount of cut is adjusted to the rate of growth; on the quality of protection; on the aims and policies of the forest owner.

Many people take it for granted that a reasonably satisfactory brand of forestry is practiced on much of our timber-producing land. A Nation-wide survey, made by the Forest Service in cooperation with other Federal, State, and private agencies as part of the Reappraisal, [20] shows that actually there is good forestry on only a small part of it. Limited to commercial forest lands, this survey considered publicly owned land and private holdings of 50,000 acres or more on a 100-percent basis. The remaining private land was covered by sampling methods; in all, some 42,000 small and medium-sized holdings, distributed to give fair representation by size of property and region, were examined. The survey dealt with: (1) The character of recent timber-cutting practices, (2) the extent to which the larger holdings are being managed for sustained yield, and (3) the quality of fire protection.

Timber-Cutting Practices Are Far From Satisfactory

The following criteria were used in rating cutting practice:

1. High-order cutting requires the best types of harvest cutting which will maintain quality and quantity yields consistent with the full productive capacity of the land. Wherever needed, it requires cultural practices such as planting, timber-stand-improvement cuttings, thinnings, and control of grazing.

2. Good cutting requires good silviculture that leaves the land in possession of desirable species in condition for vigorous growth in the immediate future. It is substantially better than fair cutting.

3. Fair cutting marks the beginning of cutting practices which will maintain on the land any reasonable stock of growing timber in species that are desirable and marketable.

4. Poor cutting leaves the land with a limited means for natural reproduction, often in the form of remnant seed trees. It often causes deterioration of species with consequent reduction in both quality and quantity of forest growth.

5. Destructive cutting leaves the land without timber values and without means for natural reproduction.

Ratings were applied to the entire acreage of "operating" forest properties, taking national forests and other very large properties by working circles. In the aggregate this included about nine-tenths of all commercial forest land in the North and South and eight-tenths in the West. "Non-operating" included tracts not operated for timber, those where fire or other agents had obscured evidences of cutting, and some remote national-forest lands that await access roads to open them for logging.

More than half of all recent cutting was rated "poor" or "destructive" (table 17). Less than one-fourth of the cutting measures up to good forestry standards.

TABLE 17.—Character of timber cutting on commercial forest land by ownership class, 1945

| Ownership class |

Commercial forest area |

Character of cutting1 | |||||

| Total | Operating | High-order | Good | Fair | Poor | Destructive | |

| Million acres |

Million acres |

Percent | Percent | Percent | Percent | Percent | |

| All lands | 461 | 403 | 3 | 20 | 25 | 46 | 6 |

| Private | 345 | 302 | 1 | 7 | 28 | 56 | 8 |

| Public | 116 | 101 | 8 | 59 | 19 | 13 | 1 |

| National forest | 74 | 65 | 11 | 69 | 19 | 1 | 0 |

| Other Federal | 15 | 12 | 6 | 37 | 32 | 24 | 1 |

| State and local | 27 | 24 | 3 | 44 | 10 | 41 | 2 |

1Percents shown refer to the operating acreage in each class now being managed under cutting practices that rate high-order, good, etc. | |||||||

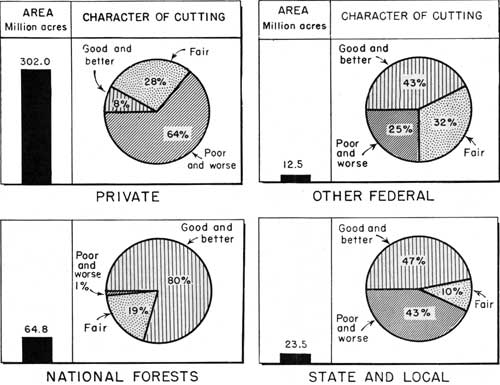

Character of cutting practices varies greatly by ownership class. On the public lands cutting is notably better than that on private lands. Two-thirds of the cutting is rated good or better, only 14 percent poor or destructive. But only about one-fourth of the commercial acreage and a much smaller fraction of potential timber growing capacity is publicly owned.

Moreover, on some public land there is much room for improvement. Good to high-order practices have yet to be attained in 25 percent of the cutting on western national forests, and on much of the 15 million acres of other Federal lands, where one-fourth of the cutting is poor and destructive. For the 27 million acres of State and local government lands, 43 percent of the cutting is in the latter categories (fig. 14).

|

| FIGURE 14.—Operating area and character of cutting by ownership class, 1945. (click on image for a PDF version) |

The practices on the 345 million acres of private timberlands carry most weight since these forests will remain our principal source of timber. Generally speaking, they are the accessible, potentially more productive lands and until recently some 90 percent or more of our timber cut has come from them.

It is largely the poor practices on most private lands that make the national showing unfavorable. About two-thirds of the cutting in private forests rates poor and destructive, hence will not keep the land reasonably productive. Although the other one-third will probably maintain a reasonably acceptable growing stock, only 8 percent is good or better.

Large private owners, on the average, treat their lands better than the small owners (table 18). Only 32 percent of the cutting on the large properties is poor or destructive while 29 percent rates good or better. These properties, however, include only about one-seventh of the private lands; they are held by about 400 of the 4,226,000 forest owners.

TABLE 18.—Character of timber cutting on private lands by size of holding,1 1945

| Size of holding |

Commercial forest area |

Character of cutting | |||||

| Total | Operating | High-order | Good | Fair | Poor | Destructive | |

| Million acres |

Million acres |

Percent | Percent | Percent | Percent | Percent | |

| Small | 261 | 224 | 0 | 4 | 25 | 63 | 8 |

| Medium | 33 | 29 | 1 | 7 | 31 | 50 | 11 |

| Large | 51 | 49 | 5 | 24 | 39 | 28 | 4 |

1Small=less than 5,000 acres (4,222,000 owners); medium=5,000 and up to 50,000 acres (3,200 owners); large=50,000 acres and more (400 owners). | |||||||

Three-fourths of the private land is in small holdings of less than 5,000 acres, averaging 62 acres. On these but 4 percent of the cutting is good or high-order. Twenty-five percent rates fair and the remaining 71 percent is poor or destructive. This ownership class represents the more formidable of private forest-management problems.

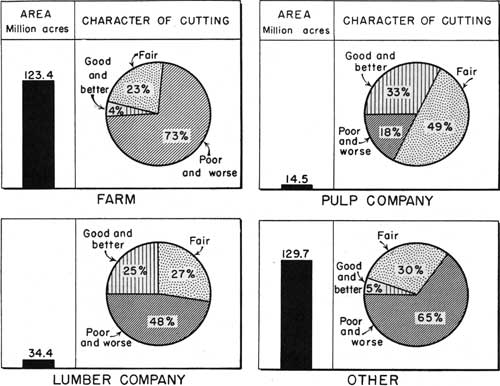

Cutting practices also vary by type of owner. They are better on pulp- and lumber-company holdings than on farm and other private properties (fig. 15).

|

| FIGURE 15.—Private operating area and character of cutting by type of owner, 1945. (click on image for a PDF version) |

About 40 percent of the privately owned forest is on some 3-1/4 million farms. Here only 27 percent of the cutting rates fair and better, and of this only 4 is good; none is high-order. The remaining 73 percent is poor or destructive.

On the lands of lumber and pulp companies—in the aggregate about 15 percent of those in private ownership—27 percent of the cutting is good or better. About 40 percent rates poor or destructive; the remaining one-third is fair. By and large, pulp-company lands get distinctly better treatment than those of lumber companies.

The other nonfarm lands, 45 percent of the total in private ownership, get little better treatment than the farm woodlands. Most of these holdings are small. They are in about 1 million properties held by a variety of individuals and companies, the majority being absentee owners.

The practices on farm woodlands and other small holdings differ little regionally. But for medium and large holdings the South leads the North and West in cutting practices by a wide margin. For example, about 52 percent of the cutting on large holdings in the South is good or better as compared with only 9 percent in the other two sections.

How Much Sustained-Yield Forestry?.

Sustained-yield management—operating a forest property for continuous production—is an important criterion of good forestry. Timber supplies can run low, even with good cutting practices, if the rate of cutting is too fast. Under sustained-yield management, the volume of cutting is planned so that, barring catastrophe, there will be annual harvests commensurate with the productive capacity of the land. If the growing stock is deficient for such annual harvests, the plan of cutting should provide for building it up while maintaining a steady flow of merchantable products at substantial though lower rates. For properties or working circles that still have a backlog of virgin timber, the cutting should be so planned that when the virgin timber is gone, annual harvests commensurate with the inherent productivity of the land may be obtained from second growth, without drastic readjustment of output.

Sustained-yield ratings were applied only to public forest lands and to about 25 percent of the private holdings—those of 5,000 acres or more. These lands have the greater part of the good and high-order cutting. The small holdings were not rated because the evidences of sustained-yield were not recognizable, in most cases. Some doubtless are being managed on a sustained-yield basis. Lands were classified in the sustained yield category when there was recognizable evidence of a planned, continuous flow of products in substantially regular or increasing quantities—provided the cutting practice was at least fair.

The data show that about two-fifths of the operating acreage in public ownership and nearly three-fourths of that in the medium and large private holdings is not on a sustained-yield basis.

| Percent of cutting on sustained-yield, basis, 19451 | |

| Ownership class: | |

| Public | 57 |

| National forest | 72 |

| Other Federal | 44 |

| State and local | 23 |

| Private (holdings of 5,000 acres and more) | 28 |

| Medium | 9 |

| Large | 39 |

| 1Weighted in accordance with the number of acres in each operating property or working circle. | |

National forests make the best showing with 72 percent. About one-fourth of the cutting on State and local government lands is rated on a sustained-yield basis.

Most national-forest land not on sustained yield is in remote localities in the West. Actually, these lands are under management which assures future output of forest products and services. They are well protected. Gutting policies are well established. But the lack of access roads and other economic factors have held cutting below sustained-yield capacity. These limitations likewise apply to some extent on other public and some private lands.

Sustained-yield management has made considerable progress on the large private holdings, with 39 percent in this category. But the owners of medium-sized holdings as a group have hardly begun sustained-yield cutting; it is practiced on only 9 percent of their holdings.

The proportion of sustained-yield practice varies considerably in different parts of the country. In the South all the cutting on national-forest lands is on a sustained-yield basis; in the North, 75 percent; and in the West, 65. For the large private holdings the corresponding break-down is: South 61 percent, North 32, and West 3.

Although significant progress has been made in the Douglas-fir subregion, these figures indicate that for the West as a whole private owners have attained little sustained-yield management. The progress in management made by industry in the West as a whole appears to have been largely in the field of fire protection and to a lesser extent in planning for new crops on cut-over lands rather than in adjusting current cutting to sustained-yield capacity.

The Status of Timber Management

To measure quality of timber management, three factors should be taken into consideration: (1) Cutting practice, (2) sustained yield, and (3) fire protection. Since it is was impracticable to apply the sustained-yield test to the 76 percent of private land in small holdings, a combination of cutting practice and fire protection ratings must suffice as the yardstick for this appraisal. In the field survey, protection was classified in four categories—good, fair, poor, and none—good protection being comparable to that on the better-protected public and private lands.

Combining the protection ratings with character of timber cutting, management grades were defined as follows:

1. Intensive management requires high-order cutting and good fire protection.

2. Extensive management requires at least fair cutting and fair fire protection.

a. Good extensive requires good cutting as a minimum.

b. Fair extensive requires fair cutting as a minimum.

3. Without management means that either the cutting practices or the fire protection, or both, rate poor or worse.

4. Nonoperating area means that the area is not being operated for timber products.

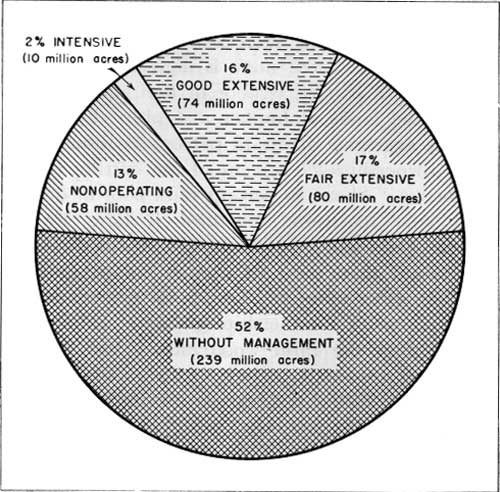

Only a little over one-third of the land is under timber management as thus defined (fig. 16). This includes only 2 percent intensively managed, 16 percent under good extensive management, and 17 percent under fair extensive management. More than half is without management; 13 percent is non-operating.

|

| FIGURE 16.—Management status of commercial forest lands, 1945. |

Only 14 percent of the publicly owned commercial forest land is without timber management, in contrast to 65 percent of the private land (table 19). Of the public lands, those in State and local government ownership rank below Federal forests in extent of management.

TABLE 19.—Management status of commercial forest lands, 1945

| Ownership class | Commercial forest area |

Management Grade | ||||

| Intensive | Extensive |

Without | Non-operating | |||

| Good | Fair | |||||

| Million acres |

Percent | Percent | Percent | Percent | Percent | |

| Private | 345 | 1 | 4 | 18 | 65 | 12 |

| Public | 116 | 7 | 51 | 15 | 14 | 13 |

| National forest | 74 | 9 | 61 | 17 | 1 | 12 |

| Other Federal | 15 | 3 | 31 | 19 | 28 | 19 |

| State and local | 27 | 2 | 37 | 8 | 40 | 13 |

1Part of these lands receives fire protection. | ||||||

The management status of national forests is best in the North, where all of their acreage is under management—26 percent intensive and 74 percent extensive. In the South, about 32 percent is intensively managed and about 60 percent extensively managed. [21]

In the West, where almost three-fourths of the commercial acreage of the national forests is located, intensive timber management has hardly begun. Eighty-one percent is under extensive management. The rest is mostly in working circles where cutting has not been feasible. Most of the extensive management on national forests is characterized by good cutting practices.

Of the private lands, those held by large industrial owners show better management than do those held by small nonindustrial and farm owners. Seventy percent of the pulp-company lands are under management; but this can be said of little more than one-third of the lumber-company lands and only one-fifth of the other nonfarm and farm woodlands. The low rating for small owners is mainly because of poor cutting practices.

In the South only 19 percent of the private operating acreage is under management, as compared with 32 percent in the North and 38 percent in the West (table 20). In all three sections more than three-fifths of the operating area would be disqualified for management because of poor cutting practices. But in the South poor fire protection alone disqualifies an additional 17 percent.

TABLE 20.—Percent of private operating area with and without management, 1945

| Section | Intensive and extensive management |

Without management | ||||

| Poor cutting |

Poor cutting and poor protection |

Poor protection | ||||

| Percent | Percent | Percent | Percent | |||

| North | 32 | 48 | 16 | 4 | ||

| South | 19 | 21 | 43 | 17 | ||

| West | 38 | 54 | 71 | 1 | ||

The foregoing helps to show where we stand now in timber management. Since comparable information has not heretofore been obtained, we can draw few conclusions as to progress beyond certain generalizations:

As late as 1938 the Forest Service estimated that only about three-fifths of the commercial forest land in the national forests was in an active timber-operating status. But subsequently the strong demand for timber has enabled the Service to extend active timber management to about 88 percent of the commercial lands and to intensify management through timber-stand-improvement cuttings. Most of the nonoperating 12 percent is in the high mountains of the West.

There are also clear indications of progress on the large holdings of lumber and pulp companies. The forest industries have the assuring of raw-material supply as an incentive and are in a key position for practicing and demonstrating good forestry. They employed about 500 technical foresters in 1945 and now have many more. They are making headway but have a long way to go. And they own only 15 percent of the private timberland.

Much less encouraging is the situation with respect to small holdings, both farm and nonfarm. Only about 18 percent of these are under extensive management and a negligible percent is under intensive management. Even the publicly supported fire-control programs, on which steady progress has been made, are notably deficient in the South and in the Central region, where more than 60 percent of the acreage in small holdings is found.

Better management of forest lands is being furthered by various industry programs such as that of the American Forest Products Industries, the "Tree Farm" and "Keep Green" campaigns, and the efforts of the Southern Pulpwood Conservation Association. Publicly financed technical assistance in harvesting and marketing has been stepped up in recent years. All these are good so far as they go. But the job of reaching more than 4 million forest owners—of bringing the whole 345 million acres under good management—is big and difficult. Herein is one of the major challenges in American forestry.

Forest practices that keep the land at least reasonably productive are essential. Though limited as yet, there is enough good private forestry in all regions and among all classes of owners to show that it is practicable—that it pays and is good business. Yet many private owners are badly handicapped in practicing good forestry. And much remains to be done in fostering a better understanding of the opportunities in private forestry and of the need for good stewardship. It will take greatly increased public aid and encouragement to overcome these difficulties.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

misc-668/sec7.htm Last Updated: 17-Mar-2010 |