|

Forests and National Prosperity A Reappraisal of the Forest Situation in the United States |

|

FOREST INDUSTRIES BASED ON TIMBER

The timber-products industries constitute one of the main channels through which the forests contribute to the economic life of the Nation. It is important, therefore, to examine the problem of timber supply in relation to these industries.

On the one hand we should have answers to such questions as these: Are the industries prepared to supply the Nation's potential requirements for timber products? What kind of timber do the industries need? What are their raw-material supply problems?

On the other hand we need to know how the pattern of industry development affects the timber resource and whether the industries are set up to provide economic outlets for what is being grown.

The Lumber Industry

Lumber manufacture is by far the largest of the wood-using industries. Its 39,000 establishments, employing an estimated 442,000 full-time equivalent workers and paying wages estimated at $774,000,000, accounted for 70 percent of the saw-timber cut in 1944.

There is an urgent demand for new housing. If we maintain a high-level economy there will be a large volume of other construction. The need for reconstruction abroad must also be considered. All together, real needs are likely to exceed the output of the lumber industry for many years.

Although per capita consumption has declined over a 40-year period, lumber is still the most widely used building material. It is the unrivaled material for many shipping purposes and finds its way into thousands of fabricated products.

Traditionally, the lumber industry has been migratory. The first sawmills in a pioneer region generally were small and served local needs. Later, the virgin timber was opened up on a large scale in order to supply other sections of the country. Large blocks of timber were accumulated or acquired by grant and these became the basis for large-mill operations. Heavy investments were made in transportation and logging facilities. The large mills tended to be clustered in strategic locations such as harbors, rivers, and rail centers. Financial pressure incident to the large investments generally tended to maintain output at a high level as long as timber was available in quantity. As the virgin timber disappeared the large mills were forced to close down. Usually, however, small blocks of timber were left because of ownership or other reasons, especially around the periphery of operations. Second growth, which was commonly neglected by the large mills, assumed increasing importance. Such timber continued to support small mills. In fact, being better adapted to cutting small blocks, scattered stands, and smaller timber, the little mills then came into their own.

Tractor logging and truck transportation have increased the flexibility of woods operations. They have made possible the economic logging of small parcels and of selected species or classes of timber that could not be handled with railroad logging. Such equipment has fostered small operations, enabling them to compete on more nearly equal terms.

The greater flexibility and mobility of logging operations increase the opportunity for good forest management and for using timber now wasted. But if not directed toward these ends, greater flexibility and mobility may, and do, lead to more destructive cutting and more complete depletion of forest growing stock.

Portable mills, most of which cut less than 1 million board feet a year, present difficult problems. Because they require little capital and are not exacting in log requirements, they open the lumber business to persons with little money and business experience. Equipment is often obsolete, poorly set up, or in need of repair. Manufacturing practice is commonly poor. Sawing for a restricted market, such as that for ties or dimension lumber, sometimes leads to excessive waste. Cost accounting is usually inadequate and there is a high proportion of business failure. Most of these small mills do not own timberland, but purchase stumpage from hand to mouth. They seldom use good forest cutting practices. Usually transient, and having no interest in future cuts from a given area, they attempt to get all they can from each tract. This ordinarily results in clear-cutting, leaving the land unproductive for many years.

The distribution and size of sawmills reflect to a considerable degree the course of timber depletion. Failing to organize a permanent raw-material supply and feeding upon a shrinking resource, the lumber industry, as previously outlined, rose and fell in one region after another in a wave of big mill operations.

A wave of big mills is now at its crest in the West. Thirty percent of the lumber output in 1942 came from 183 western mills each cutting more than 25 million board feet per year (table 21). There were only 30 mills of this size in the North and South together, and the number is growing smaller each year.

TABLE 21.—Number of mills and percent of lumber cut, by size of mill,1 1942

| MILLS | ||||

| Mill size |

North | South | West | United States |

| Number | Number | Number | Number | |

| Small | 17,031 | 18,529 | 2,331 | 37,891 |

| Medium | 78 | 419 | 294 | 791 |

| Large | 5 | 25 | 183 | 213 |

| Total | 17,114 | 18,973 | 2,808 | 38,895 |

LUMBER CUT | ||||

| Percent | Percent | Percent | Percent | |

| Small | 11.6 | 28.9 | 4.8 | 45.3 |

| Medium | 2.0 | 12.1 | 8.3 | 22.4 |

| Large | .4 | 2.0 | 29.9 | 32.3 |

| Total | 14.0 | 43.0 | 43.0 | 100.0 |

1Small: Cutting less than 5 million board feet per year. Medium: Cutting between 5 and 25 million board feet per year. Large: Cutting more than 25 million board feet per year. | ||||

The South is in an intermediate position. The era of virgin timber and big sawmills is nearly at an end, but this section of the country has more than half of all the mills cutting between 5 and 25 million board feet per year. Furthermore, it has 18,500 mills cutting less than 5 million board feet each—80 percent of them cut less than 1 million—and together these small mills produce nearly as much as the large mills of the West.

In the North, timber depletion is much further advanced and mill output averages much less. Although the total number of mills in 1942 was only about 10 percent less than in the South, their output was only about one-third as much.

Excess capacity has been a source of instability and economic weakness of the timber industry. In each region the era of big mills has been marked by expansion far beyond the permanent productive capacity of the land. Mill capacity has also been chronically in excess of market demand. But the larger mills were generally under other pressures to operate at capacity and this tended to keep prices and profits down. As a result the financial record of the lumber industry before the war was less favorable than that of other manufacturing industries.

Under such circumstances there was little incentive to conserve the basic resource or to plan for permanent operation. Marginal operations are as a rule wasteful of timber, taking only the best in hard times and, when profits are high, cutting too fast and taking small timber which should be held as growing stock.

Within the limits of timber supply and available labor and equipment, excess mill capacity allows quick expansion of output in time of need or when markets are good. However, lumber output was only 76 percent of the 48 billion board feet of estimated practical capacity in 1942, the peak year of war production. It dropped to 59 percent of capacity in 1945 when labor and equipment were short. But in 1947, with lumber prices far above those of other building materials, output surpassed that of 1942. Nevertheless, it is increasingly clear that shortage of suitable available timber has held output back in many localities.

The excess capacity would appear much greater if estimates were based on a full working year of 300 shifts for all active mills rather than on practical capacity. Such a theoretical capacity in 1942 would have been 77 billion rather than 48 billion board feet. Normally, however, many small mills operate only part of the year. In some regions this is desirable because employment in these mills supplements farm employment.

Operators who have a good supply of timber are now in a favorable financial position. There is every indication of a sustained demand that will absorb as much lumber as the industry is likely to produce if prices are not too high. The market will, in general, be less selective than before the war—with respect to species, grades, and sizes. Such less desirable species as beech, the true firs, and hemlock, for example, will find a more profitable market. Some markets may be lost because of short supply and high lumber prices, but the relation of supply and demand will continue to favor the operators who own their own timber. On the other hand, those who do not own timber enough to meet their needs will find competition with other forest industries for stumpage more intense. Manufacturers of pulp and paper, veneer, cooperage, and other products are, to an ever increasing extent, obliged to obtain their raw material from the same sources as the lumber industry.

All these factors vindicate the foresight of progressive owners who undertook sustained-yield management a decade or more ago. The more favorable outlook is largely responsible for the increasing number of operators interested in good forest practice today. More than one-third of the land owned by lumber companies is now given some degree of planned forest management, and one-fourth of the cutting on lumber-company land is good or of high order, [22] by far the best showing being in the South.

The Pulp and Paper Industry

Pulp and paper manufacture ranks second to lumber among the timber industries. In 1944, according to Forest Service estimates, it employed 175,570 full-time equivalent workers and paid total wages of $316,600,000. Several facts concerning this industry may be emphasized: (1) There is an expanding market for its products; (2) it depends on foreign countries for a substantial part of its raw-material supply; (3) it has a high degree of internal integration, and (4) it has large plant investments.

The use of paper and paperboard in this country has expanded from 57 pounds per capita in 1899 to 119 pounds in 1919, 243 pounds in 1939, and 317 pounds in 1946. The peak has probably not been reached. Furthermore, new uses for wood pulp such as rayon, cellophane, photographic film, and plastics have increased the demand, and chemical research continues to find new uses.

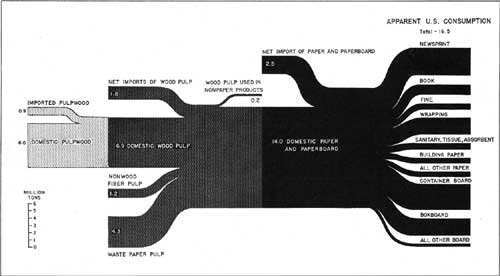

The raw-material supply for paper and pulp products is complex (fig. 17). Imports come in at all stages—as pulpwood, wood pulp, and paper and paperboard—and reuse of paper adds substantially to the domestic supply of raw material.

|

| FIGURE 17.—The flow of pulpwood and other raw material into paper and paperboard products, United States, 1939 (in terms of million tons of wood pulp). (click on image for a PDF version) |

The five standard pulp-making processes differ in wood requirements, yields, and products. Forty-five percent of the 10-million-ton pulp output in 1944 was produced by the sulfate process. Almost any species can be used for sulfate pulp; but most of it is made from southern yellow pine. The yield is less than half the wood weight. Sulfate pulp is used principally for wrapping and bag papers and paperboard. However, bleaching makes it suitable also for newsprint and higher grades of paper.

Twenty-four percent of the 1944 output was by the sulfite process, which is used for the best grades of paper, rayon, cellophane, and other pure cellulose products. Long-fibered nonresinous conifers—the spruces, balsam firs, and hemlock—are the chief species used and the yield is about 50 percent. This is the chief chemical process in both the North and the West.

Mechanical or ground-wood pulp, the major component of newsprint paper, and the most exacting in its requirements, accounted for 15 percent of the 1944 output. Only the long-fibered light-colored spruces, balsam firs, and western hemlock are suitable for this process, but the yield is about 90 percent by weight. Most of the ground-wood output is in the North.

The soda process accounted for only 4 percent of the 1944 output. It is used for pulping hardwood species, chiefly aspen and cottonwood in the North, and the yield is about 50 percent. Mixed with sulfite pulp, it is used for book and magazine paper.

The semichemical processes, accounting for 5 percent of the output, use almost any hardwood. The yield is 70 to 80 percent, and the principal product is corrugated board.

In addition to the standard pulp-making processes, the production of defibrated, exploded, and asplund fiber for manufacturing building board, insulating board, other fiber boards, and roofing is growing into a substantial industry—accounting for 6 percent of total pulp output in 1944. Using a wide variety of both conifers and hardwoods, these new processes hold promise for all forest regions.

The pulp and paper industry is compact. In contrast to the thousands of sawmills, there were only 237 active pulp mills in the country in 1944, all but 25 integrated with paper mills. The mills are located chiefly near the Atlantic and Gulf seaboard, in the Lake States, and in the Douglas-fir subregion.

Unlike the lumber industry, the paper and pulp industry is running at full capacity. During 1946, production reached 110 percent of rated plant capacity, yet the demand for many paper products was not met. Newsprint paper, much of which is imported, was especially short.

The pulp and paper industry is perhaps the most stable of the timber industries. Before the war an integrated sulfite pulp and paper mill of economic size called for an investment of 3.5 to 4.0 million dollars. For kraft pulp and paper minimum investment was 7 to 8 million dollars. Since such mills require a long amortization period, an assured wood supply becomes doubly important.

The industry owned about 15 million acres of forest land in 1944. This acreage is increasing, but few companies own enough to supply all their needs. Many pulp manufacturers have Canadian affiliates and own timber in that country, some of it acquired expressly for supplying plants in the United States.

Pulp and paper companies have been in the forefront of private owners in adopting forestry practices. More than two-thirds of the industry's lands is under management. In 1945, 33 percent of the cutting on pulp-company lands was "good" or "high-order"; another 49 percent was rated "fair." Only 18 percent was poor or destructive. [23]

Although the pulp and paper industry has adopted aggressive policies in forest-land acquisition, made a good beginning in forest management, and kept alert to improvements in technical processes of manufacture, its wood-supply problems are by no means solved.

Wood supply is a critical problem for many of the mills in New England and New York. Spruce and fir are in especial demand. Much of the supply comes from Canada. In New York some operators go into the woods for as little as 3 cords per acre. Premature clear-cutting of pulpwood timber is a common practice and this works against a shift to partial cutting methods which would give greater stability in the long run by maintaining productive growing stock.

In the Lake States, depletion of the preferred pulpwood species is even more advanced. Most of the spruce and fir comes from Canada, and high level production is being maintained by the increased use of jack pine, aspen, eastern hemlock, and hardwoods. Some spruce is now being obtained from Colorado, and lodgepole pine is shipped in from Montana.

The South now produces almost one-half of the Nation's total pulp output. The industry has expanded phenomenally there during the past 15 years. In some localities where new mills are planned, it is questionable whether the larger needs for wood can be met. Although most of the southern pulp and paper companies are managing their own timberlands well, nearly one-half of the industry's wood supply comes from other lands, where growing stock is being depleted by heavy cutting of small second growth.

In the Pacific Northwest, the dominant sulfite mills have already expanded close to the limits of the supply of the favored species—western hemlock and Sitka spruce. There are, however, large volumes of balsam firs, Engelmann spruce, and mountain hemlock farther up in the mountains which have been little used. With more hemlock going into lumber and plywood, sulfite pulp manufacturers have been actively expanding their timberland holdings. Further growth of the industry will doubtless be chiefly in the use of Douglas-fir for sulfate pulp. A large volume of low-quality logs and logging waste is available for such use.

Part of the deficiency in our domestic pulpwood supply may eventually be met by building pulp and paper plants in Alaska. The coastal forests, predominantly western hemlock and Sitka spruce, are well suited for paper making and could supply 1.5 million cords of pulpwood annually. This would be about 7 percent of our potential requirements.

Methods of procuring pulpwood vary. Much is purchased from farmers or independent loggers, often through brokers working in assigned districts. In such buying, the pulp and paper industry is generally able to outbid the lumber industry. Some of the wood is obtained from other timber industries. Imports from Canada are substantial in both the North and the Pacific Northwest.

Dependence upon contract buyers, who have little interest in either the permanence of the manufacturing plant or the continued productivity of the forest, is a disturbing element in the South and North. Possibilities exist for the creation, at strategic locations, of open pulpwood markets or timber-products exchanges where producers and consumers could transact business to mutual advantage.

The base of the industry's wood supply could be broadened by more general integration with other industries. Pulpwood demand can be met in part from thinnings in young stands, from species not favored for lumber or other uses, and from waste in sawlog operations or in lumber manufacture. Integrating the production of a combination of products, the specifications of which represent a progression in size and quality, should be profitable for small timberland owners, should reduce wood costs in the pulp industry, and should save timber.

The Veneer and Plywood Industry

The veneer and plywood industry has grown rapidly in the past 25 years. Its employment in 1944 is estimated as the equivalent of 54,170 full-time workers. Although it consumed only 6 percent as much timber as the lumber industry, and 30 percent as much as the pulp and paper industry, these figures do not measure its potential importance.

The industry has three main types of products: (1) Face veneers, made chiefly from high-quality hardwoods and used in furniture, cabinetmaking, paneling, and similar manufactures; (2) container veneers, made from southern pine, ponderosa pine, sweetgum, tupelo, birch, beech, maple, elm, cottonwood, etc., and used for orange and egg crates, baskets, hampers, and boxes for shipping fruits, vegetables, and other commodities, and crating for refrigerators, radios, etc.; and (3) plywood, made chiefly from Douglas-fir, and used for construction, door panels and other millwork, small boats, refrigerator cars, and hundreds of other purposes. New waterproof glues, improved methods of bonding, and the process of molding into various curved shapes have added greatly to the utility of plywood. In almost all its major construction uses, plywood is interchangeable with lumber and has several advantages. It can be produced in large sheets free of knots and other defects and can often be put into place with less labor.

Of the 1.5 billion board feet, log scale, used for veneer and plywood in 1944, 58 percent was hardwood and 42 percent softwood. Over half the total production of hardwood veneer was for containers. Furniture veneer, although in great demand and bringing high prices, constitutes a small part of total production.

Hardwood veneer plants, of which there are about 600 varying greatly in size, are widely dispersed throughout the East. Container production is concentrated chiefly in the South and face-veneer production in the Central and Lake regions.

In contrast, the softwood plywood industry is compact. At the end of 1944, there were 34 active plants, 32 of them in the Pacific Northwest and 2 in California, all but a few large and modern. Total capacity is about 2,150 million square feet (3/8-inch, 3-ply basis), but peak production (1942) has been only 1,850 million square feet.

Large, good-quality logs used by the veneer and plywood industry are becoming scarce. There are current or imminent shortages of logs for face veneers in each of the important hardwood regions. The Central, Middle Atlantic, and Lake regions probably have less than 10 years' supply of high grade veneer stumpage, at present rate of cutting. Possibilities of expanding the face-veneer industry in other regions are small. Container veneer, however, has less exacting requirements and there is enough hardwood to maintain the current level of production.

The hardwood plants buy logs from every available source—lumber manufacturers, independent loggers, farmers, importers (about 20 percent of face veneer). Attractive prices can be offered and logs can be transported long distances. Buyers for the larger concerns scour the country, purchases usually being made in small lots. High-quality face-veneer stumpage is often purchased as individual trees.

The softwood plywood industry of the Pacific Northwest is little more than two decades old. Yet there is an acute shortage of peeler logs in the Puget Sound, Grays Harbor, Columbia River, and northern Oregon coast areas, which had about 75 percent of the total installed capacity in 1942. The industry must adapt itself to new conditions.

Procurement of peeler logs for softwood plywood was almost exclusively in the open market until about a decade ago. Between 1937 and 1942 softwood plywood production more than doubled, while open-market supplies of all grades of logs decreased sharply. By 1944, only one-fourth of the industry's requirements was being drawn from log markets. Many good peeler logs now go into lumber.

The softwood plywood industry does not own enough timber to maintain production. It still relies largely on other owners because the high-grade logs and bolts it uses represent so small a part of the timber stand that investment in timberlands would be out of proportion to the size of the business. Plants are generally located in communities with sawmills, but it would be desirable to go further in integrating log procurement with that of the lumber industry.

However, to maintain output the Douglas-fir plywood industry will have to use lower-quality logs, and this will cause more direct competition between plywood and lumber mills for log supplies. It will also require more economy in the industry—use of poor-quality material for cores and backs, and patching of defective veneers. Since this inevitably means higher operating costs and lower quality of product, the plywood industry's competitive advantage in the market for high-quality logs will gradually be reduced. Nevertheless, there will doubtless be opportunities for new veneer mills in localities where the timber is still to be opened up.

There is not much prospect of expanding output by greater use of less desirable species of timber in other regions. Difficulties in drying and sanding, and the tendency to checking and glue staining, restrict the use of western hemlock and noble fir. The generally coarse and defective Douglas-fir in eastern Oregon, eastern Washington, California, and the Rocky Mountain regions is not suitable for plywood under present standards. The white fir of California is also apt to be highly defective. California red fir holds some promise but will also be used for lumber. The use of ponderosa pine and sugar pine for veneer might be expanded, but again this would run into competition with the lumber industry.

Other Timber Industries

Space permits only brief reference to other timber industries. Some of these illustrate critical situations arising from shortages of timber of the species or quality required. Others, although small in total output, may be valuable links in local integration for more effective use of timber in the woods and mill. Still others may furnish new employment and income in communities that lose major timber industries.

The output of the wood shingle industry is declining. This industry is based almost entirely on western redcedar and is concentrated in a few localities in the Douglas-fir subregion. The output of 3.4 million squares in 1944 was only one-third of the peak production about 35 years ago. The capacity of installed machines is about 12 million squares. About 25 percent of the wood shingles used in this country come from British Columbia. Because cedar occurs as scattered trees, the industry depends upon purchased stumpage except where affiliated with sawmills. With the passing of open log markets, many mills have difficulty in obtaining logs. The industry faces increasing competition from asphalt roofing and its future is doubtful. Of passing interest is the fact that defibrated wood is being used increasingly as base for asphalt roofing.

The tight cooperage industry is declining because of depletion of suitable timber. Most of this industry is in the Southeast, West Gulf, and Central regions. Suitable white oak, the chief species used, commands fantastic prices and waste is very great.

There is no shortage of raw material for the slack cooperage industry, which is more widely scattered and uses many species, including pine, redgum, spruce, elm, and Douglas-fir.

Hewing of cross ties is wasteful and the range of tree sizes that can be used is narrow. Because timber of tie size is at the threshold of its most valuable growth, tie cutting usually impairs forest-growing stock. In the South, hewn ties are made chiefly of southern yellow pine and oak. In the West, lodgepole pine and Rocky Mountain Douglas-fir are the chief species for hewing. Hewn ties constitute only a small part of all ties used.

Cutting of round mine timbers usually destroys immature growing stock. It is largely confined to the Middle Atlantic and Central regions. Since there is wide latitude as to species and size, most of the need for mine timbers could be met from thinnings and improvement cuttings.

The pole industry now uses chiefly southern pine. Use of western redcedar has declined because of shortage of suitable timber. Lodgepole pine, available in large quantities, is being more widely used to supply rural-electrification needs.

Cutting of piling commonly takes the form of thinning, because of exacting specifications that bar small timber and admit only the straightest trees. Piling is cut chiefly from southern pine and Douglas-fir. Because it brings high prices, cutting for this product is usually very profitable to the timber owner.

The production of naval stores from the gum of longleaf and slash pine trees is important in the South. With proper management gum production may be effectively integrated with the production of pulpwood and sawlogs. When so integrated it opens the way for more intensive forestry than might otherwise be possible by providing substantial additional income.

Timber Industries in General Handicapped by Waning Timber Supply

The foregoing review of the principal timber industries points to timber shortage as a major handicap to sustained output. Other factors—especially skilled labor and equipment shortages—influence the situation currently, but raw material is basic and the major forest industries are finding the procurement of suitable stumpage more difficult and costly than in earlier years.

Local shortages of timber suitable for the established industries are critical. They are not fully revealed by regional data on timber volume and growth. In many localities the timber industries have been based on certain favored species, making no use of, and often destroying, large volumes of intermingled less desirable species. Sometimes it has been possible to go back over the land to harvest the species formerly considered unmerchantable, but industries that depend for profitable operation on superior species such as western white pine in the Northern Rocky Mountain region or sugar and ponderosa pine in California, must discount estimates of total timber volume to allow for the species that they cannot market to advantage.

Exploitation of favored species in the past aggravates the raw-material problem now. The removal of the best trees of the choice species often leaves the land in possession of a poor-quality stand dominated by low-value species. Such conditions are generally unfavorable for a new crop of the more valuable species. Thus poor-quality hardwoods have taken over large expanses of eastern forests that formerly supported valuable mixed timber. And high-grading is being practiced also in the mixed conifer types of the West.

The availability of raw material for the timber industries is further limited by transportation factors. Half of our saw timber is in the West, yet many of the established industries there will have to close because they can no longer get enough timber. New roads must be built into undeveloped country to make much of the timber available.

Ability of established industries to get timber from new localities is sometimes limited by the inadequacy of the public highway system or restrictions imposed upon highway use. The bulk of the timber now moves to the mills by motor truck. In many localities the public highway system will not stand such heavy traffic, or the grades and curves make log hauling impracticable. To overcome such limitations, some western timber operators have constructed their own roads paralleling public highways. Where the highways must be used, license fees or laws regulating truck loads, speeds, etc., often varying from State to State, add to the cost of transporting both raw material and finished product.

Railroad freight charges also have an influence on raw-material supply. In general, other things being equal, the farther the raw material must be hauled the less the manufacturer can pay for it at the loading point. Consequently the margin for stumpage goes down as shortage of nearby timber forces a manufacturer to go farther afield. This encourages "high-grading," species discrimination, and other wasteful practices in woods operations which, as previously pointed out, adversely affect future timber supplies. Indirectly, freight charges in getting the manufactured product from mill to consuming markets also have a bearing on timber supply. While these tend to be passed on to the consumers, the more distant manufacturers must absorb freight differentials in order to compete with those more favorably situated. This limits how far they can go and what they can pay for raw materials in the same manner as freight or other transportation charges in getting the raw material to the mill.

Industries Not Geared to Permanent Timber Supply

The impact of timber shortage on the forest industries has just been considered. A complementary question is how the location and character of these industries have affected the timber resource.

Too much manufacturing capacity in certain localities has led to overcutting of tributary forests. There are numerous examples of this now in the Pacific Northwest. Grays Harbor, for example, had 35 active sawmills in 1941 capable of producing well over 1 billion board feet a year. The cut in 1941 was 810 million board feet, of which 650 million was Douglas-fir and redcedar. Yet the tributary forests could sustain a cut of only 206 million board feet of these species.

One fundamental reason for such lack of balance is that the timber industries in general have been organized on a liquidation basis. Only recently have a significant number of enterprises been planned for continuous operation. It was inevitable that competitive exploitation of the original timber without regard to the sustained-yield capacity of the forest would lead to an overconcentration of plants in locations such as Grays Harbor, Puget Sound, and the Columbia River which combined easy access, to a large volume of high-quality timber with cheap transportation to major consuming markets.

Excess plant capacity remains a problem in the older regions. In both the North and South, thousands of small sawmills with far greater capacity than the forests can sustain are a constant threat to essential forest growing stock and satisfactory forest management. Furthermore, New England, New York, and the Lake region have more pulp mills than their forests can support. Even in the South, concentration of pulp and paper mills at favorable points along the coast has led to rapid depletion of the local timber supply.

During recent years there has been a significant accumulation of forest land by manufacturers concerned about the future of their operations. Those needing more land frequently buy from those going out of business. Tax forfeiture of cut-over land has subsided. Yet lumber companies and pulp and paper manufacturers together own little more than one-tenth of all the commercial forest land. Obviously, much of their raw-material supply must come from other owners. In parts of the West, there is much interest in cooperative sustained-yield units whereby private forest land may be blocked up with adjacent government timber under a coordinated cutting plan. Such developments tend to strengthen ownership and give stability to a larger segment of the industrial timber supply. Acquisition of forest land by public agencies also works toward these ends.

Competition for stumpage aggravates timber depletion. Manufacturers who own enough land can plan on a permanent supply. Those who must depend on the purchase of stumpage are often forced to compete with one another. In many parts of the country the scarcity of stumpage has led to premature cutting of young stands. Furthermore, competition for stumpage has often resulted in liquidation of residual growing stock by owners who previously had undertaken partial cutting. And because of this, operators who may strive to keep their own lands productive sometimes disregard future productivity when cutting purchased stumpage.

The small private holdings, including the farm woodlands, are in general suffering most from the scramble for stumpage. Yet an active demand for timber should be conducive to good forest practices on such lands. Farmers need to be shown that timber growing can be an integral part of their business and small owners, whether farmers or others, will often be better able to withstand pressure for destructive cutting if organized into cooperative associations through which output may be more effectively channeled into industrial use.

The adverse effects of competition for stumpage could be reduced in some sections by organizing timber-products exchanges. Experience with other commodity exchanges indicates that this would tend to assure the timber growers fair prices and good outlets, while the manufacturers would find a more dependable source of raw material.

Integration of wood requirements for various products should lead to more orderly timber use and better forestry. To put each cubic foot of wood to the highest use it can serve—high-grade logs into high-quality products, and low-grade material into pulpwood, fuel wood, or similar products,—means a continual search for ways to eliminate waste and reduce costs. Integration within a single company may not always be feasible, but when it can be accomplished it usually results in more complete utilization and lower costs. For example, a combination of sawmill, pulp and paper plant, veneer mill, and chemical plants using wood and pulp-mill wastes may fit operating conditions in the Pacific Northwest. An outstanding example may be found in the integrated operations of one of the large companies at Longview, Wash.

Where plant integration is not feasible, the raw-material supply for independent sawmills, pulp mills, and specialty manufacturers may be integrated, as already suggested, through timber-products exchanges or by cooperative action among the manufacturers, the producers, or both. At any rate the presence of diversified timber industries in a given locality may afford ample opportunity to sell all kinds of timber to advantage. Such situations exist, for example, in southern New Hampshire and at Gloquet, Minn. They help make good forestry practicable.

In summary, the raw-material problems of the timber industries are matters of balance and emphasis—a balance of manufacturing capacity with sustained-yield capacity of the forest: emphasis on timber as a crop rather than a resource to exploit. In general, the timber industries have been organized, financed, and operated solely to convert standing timber into other forms of wealth. Since the profit, often chiefly in stumpage value, was realized by the conversion, and the owners until recently had no part in the growing, those who had access to market generally liquidated as fast as they could. Usually this meant taking only the best trees of the favored species and waste of much more than was used. Often the result was "boom and bust" for dependent communities. For permanence and stability, the timber industries should be geared to the productivity of the forest and designed to make full economic use of all that grows on the land. They should give more attention to timber growing.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

misc-668/sec8.htm Last Updated: 17-Mar-2010 |