|

Backpacking in the National Forest Wilderness...a family adventure PA-585 |

|

TRAVEL LIGHT

Experienced backpackers pride themselves on being able to travel light. With many, weight saving is almost a fetish; with all it's a game. Rugged, sure footed men will seriously explain that they cut towels in half and saw the handles off toothbrushes to save ounces. They measure out just the right amount of food needed and put it in plastic bags, which are lighter than cardboard. They carry scouring pads with built-in soap, thus eliminating a bar of soap and a dishcloth. There are dozens of such tricks to save the ounces that add up to pounds.

How much should one carry? In the Rupe family Jack, the father, started with 51 pounds, 5 of which were fishing gear. Harriet, the mother, started with 38 pounds. "After I fell in the creek," she says, "Jack added part of my gear to his already overloaded pack."

Seventeen-year-old Jackie also carried 38 pounds, while her younger sister Barbara, 11, took 26 pounds. Bret, 15, carried 48 pounds. Nine-year-old Wade had no trouble with his 26 pounds.

Most people try to get by with lower weights: 30 pounds for a woman (maximum 35), and 40 pounds for an adult male (50 pound limit). Actually, it all depends upon the physical condition and experience of the individual, the terrain to be covered, the length of the trip, and the time of year.

When figuring weight, count all items—the cup on the belt, the camera and light meter around the neck. Most backpackers keep such appendages to a minimum. They are easily lost, and since they may catch on low brush, can be a safety hazard.

|

| The Ropes check weights on bathroom scales which they leave in the car. First they weigh in without pack; then with pack. Here Dad is taking some of the gear from pack overloaded by young son, Wade. F-503160 |

WHAT DO I NEED?

Pack • Tent or tarp for a roof overhead • Sleeping bag • Air mattress • Cooking utensils • Dishes—plates, cups, and cutlery • Food: 1-1/2 pounds per person per day • Clothing: slacks or jeans—2 pair, long-sleeved cotton shirt—at least 2, wool shirt or sweater, parka or wind-breaker, wool socks—2 changes, underwear, camp shoes and socks, rain gear (rain shirt, poncho, or plastic raincoat), handkerchiefs • Flashlight with extra batteries and bulb • First aid kit—make your own: band aids, compresses, 4-inch Ace bandage, triangular bandage, antiseptic, aspirin, eye wash, adhesive tape • Bug dope • Maps and map case • Suntan lotion • Dark glasses • Rope (nylon cord) • Toilet tissue • Trowel • Knife • Ax or hatchet • Small pliers • Matches • Soap and towel • Needle and thread • Safety pins.

Don't rush out and buy all these. Most people have something they can "make do."

A GOOD UNDERPINNING

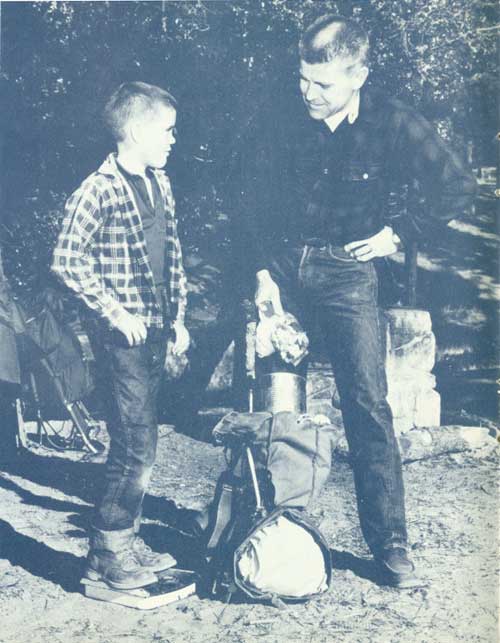

There is probably nothing about which experienced backpackers are more definite than boots. Ask 15 hiking friends what kind of boot to get, and there will be 15 different answers.

"Use heavy sneakers well padded with wool socks."

"No support in those, get an ankle-high boot with moccasin top stitching."

"That height is wrong, use 7-inch boots—protection against snakes!"

"What's the matter with boots that come halfway up the calf of the leg?"

"Too stiff. Try the shoepac rubber-bottomed boot with leather top for wading through low streams."

"They're too hot and sweaty in summer and too cold in winter. Get boots made to order."

"That's a waste of money."

And so the discussion goes on endlessly. All the types of boots have advantages and disadvantages.

Sneakers are cooler and definitely cheaper. For young people with growing feet, the heavy-soled ankle-high sneaker is probably best. Most youngsters find them comfortable and the family budget permits a new pair each year.

Rubber is obviously good where the going is wet. Many a hiker traversing bog country uses the shoepac exclusively. Leather is generally the most popular material for all-around hiking shoes. It wears well, is soft and pliable. It can be waterproofed to shed rain and snow.

Leather soles on boots, however, are slippery. Staunch oldsters still use them with hobnails, but recreation hikers use rubber, synthetic, or cord soles. When the original sole begins to wear, thick rubber lug soles can be put on, which grab on rocks. Many hikers have lug soles applied at time of purchase.

At first, some men use work shoes that they already have around the house, or the boots obtained in military service. Many women use saddle shoes or other sturdy flat-heeled oxfords with rubber soles.

This year for the first time all the Rupes had 7-inch boots. In the past only the parents had boots; the children used sneakers.

Summing up—boots should fit comfortably over two pairs of socks, one thin and one thick. They should protect the ankles, support the foot, and withstand long mileage on rocks and roots. They should be broken in before the trip—but don't start out with a pair too well worn. Mountain trails are tougher than city park paths.

Words of caution: ski boots are for skiing, and cowboy boots are for horseback riding. Footwear with eyelets and lacing have proved best for hiking, and don't forget that extra pair of laces.

AN EASY-RIDING PACK FOR A MERRY HEART AND A LIGHT STEP

There are three major types of packs used today: the packboard, the frame, and the rucksack. Each of uses the modern version of the packboard—a lightweight aluminum packframe, angled at the shoulder and waist to fit the contours of the body with only nylon bands resting against the back. These come in sizes to fit different weights and heights. Straps from the lower part of the frame fasten just below the waist, placing the weight of the pack on the hips. If the waist strap is released, the frame will hug the back, so that the pack will not swing a person off balance when he is jumping from rock to rock or hiking along narrow ledges.

The frame may be bought with or without a pack attached. The Rupes preferred the former, with compartments and outside pockets. They report that at no time does the pack attached to the frame touch the body.

These deluxe packs are one of the latest backpacking investments. Even now, those used by the two younger children are reproductions made by Jack. When they first started this sport they used wooden packboards and an old Army frame pack. The wooden packboard is a rigid and sturdy contraption with shoulder straps and a waistband, but no contours. The load that can be put on them is tremendous. At best they are uncomfortable.

The Army framepacks were developed during World War II and are still available at low cost. Also there are commercial variations, lighter in weight and more comfortable.

Hints:

—Outside pockets are mighty handy for items needed during the day.

—Attach foam rubber pads to the shoulder straps. They come ready made from almost any sporting goods store.

—Place heavy items toward the back of the pack.

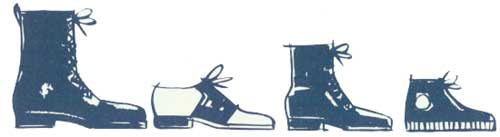

A ROOF OVERHEAD

To take a tent or not to—that is the backpacker's question. A bed beneath the stars has romantic appeal, but in most parts of the country, it's best to be practical and carry some kind of shelter. There's nothing more uncomfortable than waking up to rain or snow in the face and a soggy sleeping bag.

The Rupes carried tubular plastic material, similar to that used by dry cleaners, except that it is wider and thicker. For it they paid less than 75 cents a yard, and their tents were about 4 yards long to accommodate two. The plastic weighs little and folds up into a small package. Putting a poncho under it for a ground cloth is advisable: it is easily punctured.

There are lightweight tents designed for backpacking that have the advantage of more protection. With a floor and a netting over the entrance they are insect proof, animal proof, and waterproof. Stakes slightly larger than a nail and lightweight telescopic aluminum poles rolled in the tent make a compact package.

Tent material presents a problem. Breath condenses in the watertight nylon tent causing real dampness. Waterproofed cotton, on the other hand, isn't completely watertight. Many backpackers get around this by using a cloth tent and stretching a nylon or plastic fly over it.

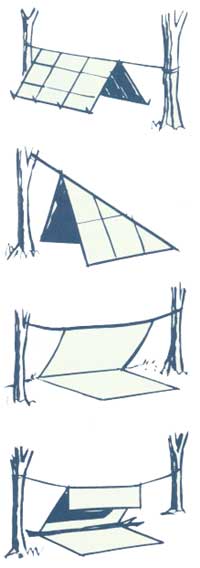

The shelter need not be a tent. A nylon ground cloth or a large piece of plastic at least 9 x 12 feet, preferably with grommets along the sides, can be tied up to trees to give shelter. Some people use their ponchos for this purpose.

There are numerous ways to fix such shelters. String a rope from one tree to another, head high or less. Throw the plastic over the rope and attach corners to other trees, one end lower than the other. Under this shelter meals can be prepared in case of rain and three or four people can sleep. For small shelter omit the ridge rope and attach the tarp to trees so that it slants.

For a one-man shelter, put part of the ground cloth on the ground as a protection for the air mattress. Then run the ground cloth on a slant over the air mattress and hitch to overhanging branches, thus forming a "V" in which to sleep. If the open end of the "V" is up against a big log, the backpacker has a snug little nest in which to crawl for the night.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

PA-585/sec4.htm Last Updated: 12-Sep-2011 |