|

SEARCH FOR SOLITUDE: Our Wilderness Heritage |

|

OUR WILDERNESS HERITAGE

Wilderness is part of the American heritage. This Nation was spawned in wilderness, and from the beginning of settlement it has obtained sustenance from the boundless forests on every hand.

Viewed with awe and some misgivings by early settlers of the New World, the American wilderness has been interwoven into the Nation's folklore, history, art, and literature. Even today, these wide expanses of forested mountains help shape the character of our youth.

|

| (click on image for a PDF version) |

The wilderness that witnessed the birth and early growth of this Nation no longer spreads from ocean to ocean. But neither has all of it been tamed. Many of these untamed lands, majestic reminders of primeval America, are parts of the National Forests of the United States.

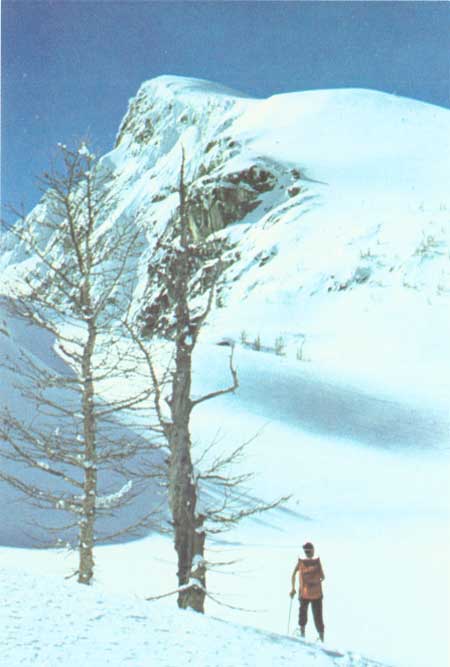

Here, as wild and as free as ever, 9,925,352 acres of wilderness in 60 areas are held in trust by the Forest Service of the U. S. Department of Agriculture for the use, enjoyment and spiritual enrichment of the American people. Another 4,363,954 acres in 28 Primitive Areas are being reviewed under provisions of the Wilderness Act of 1964 to determine their suitability for inclusion in the Wilderness System.

The Forest Service bears with pride its stewardship of these unique lands and is dedicated to keeping them intact for this and future generations.

Within these plantations of God a decorum and sanctity reign, a perennial festival is dressed, and the guest sees not how he should tire of them in a thousand years. In the woods we return to reason and faith. —Ralph Waldo Emerson. (1803-1882)

On September 3, 1964, when the President signed into law the bill creating the National Wilderness Preservation System, it assured for our time and for all time to come that 9 million acres of this vast continent would remain unchanged except by the forces of nature.

The new law designated 54 National Forest areas as units of the National Wilderness Preservation System to remain forever natural except for special provisions for certain restricted commercial uses. Included were the 9.1 million acres of wilderness, wild, and canoe areas previously established by the Department of Agriculture.

Thirty-four National Forest Primitive Areas — 5.5 million acres — were to be reviewed before September 3, 1974, as to their suitability for addition to the Wilderness System. Also to be reviewed were all roadless areas of 5,000 acres or more in the National Park System, as well as all such areas and roadless islands, regardless of size, in the national wildlife refuges and game ranges. Areas to be reviewed may be added to the System only by subsequent acts of Congress.

Only in America have such positive measures been taken to preserve wilderness as a national resource. In the new conservation of this century, our concern is with the total environmental relationship between man and the world around him. Its object is not only man's material welfare but the dignity of man himself.

The Congress can justly be proud of the contribution of foresight and prudent planning expressed by this measure to perpetuate our rare and rich heritage. Generations of Americans to come will enjoy a more meaningful life because of these actions.

In wildness is the preservation of the world. —Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862)

PROLOGUE

One of the first Americans to sense a threat to wilderness, and to speak out for the preservation of wildlands, was Thoreau. Even then, just over 100 years ago, the need was not immediate. Much of the land was still wild, and there seemed to be more space for expansion than the country would ever need. But before many years had passed, our building Nation was reaching toward the most remote corners of our land. For a few conservationists who looked to the future, this signaled a warning that without protection none of our lands would remain forever wild.

President Theodore Roosevelt, in 1905, declared that the object of forestry is not to "lock up" forests, but to "consider how best to combine use with preservation." Under enabling legislation passed that year, the present Forest Service was created.

|

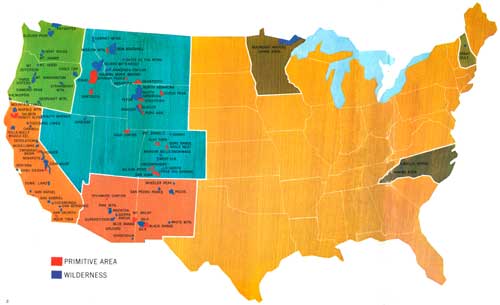

| T. J. Lake and Mammoth Crest in the John Muir Wilderness, Inyo National Forest, California F-519722 |

In 1906, the area of forest reserves was increased to 107 million acres, timber sales tripled, and grazing permits were issued. Subsequent legislation and Presidential proclamations increased the acreage of the National Forests and provided authority whereby the Chief of the Forest Service, with the approval of the Secretary of Agriculture, could exercise his judgment as to priorities of land use.

So began the Forest Service concept of wilderness land management—that of designating as wilderness those lands predominantly valuable as wilderness so as to manage and maintain them indefinitely for their unusual and unique values.

Thus, nearly 50 years ago, the Forest Service of the Department of Agriculture pioneered in the preservation of America's wilderness heritage. Farsighted leaders recognized that the wilderness resource, once developed, was lost forever, and that lost too were those things inherent in its primeval character—recreational, scientific, educational, and historical values of great benefit to the Nation and its people.

The richest values of wilderness lie not in the days of Daniel Boone, nor even in the present, but rather in the future. —Aldo Leopold (1887-1948)

WHAT IS WILDERNESS?

Wilderness is both a condition of physical geography and a state of mind which varies from one individual to the next. It is part of the eternal search for truth that involves man's desire to know himself and his Creator.

The Wilderness Act of September 3, 1964, accepted and established as national policy a Forest Service program to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness. Because the word "wilderness" means different things to different people, that Act includes a definition which, in part, says that it is Federal land "... where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man ... retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvements or human habitation ... generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man's work substantially unnoticeable ...."

Wilderness shaped our national character as our forefathers met and conquered its early challenge. The National Wilderness Preservation System will assure all future Americans of a continuing opportunity to test their pioneering skills.

|

| Chinese Wall in the Bob Marshall Wilderness, Flathead National Forest, Montana F-519723 |

Aldo Leopold, one of the foresighted Forest Service leaders who pioneered the wilderness concept, once expressed his wilderness philosophy when he referred to the early Mountain Men, such as Jim Bridget and "Kit" Carson, as follows: "No servant brought them meals . . . No traffic cop whistled them off the hidden rock in the next rapids. No friendly roof kept them dry when they mis-guessed whether or not to pitch the tent. No guide showed them which camping spots offered a night-long breeze, and which a night-long misery of mosquitoes; which firewood made clear coals, and which would only smoke. The elemental simplicities of wilderness travel were thrills . . . because they represented complete freedom to make mistakes. The wilderness gave . . . those rewards and penalties for wise and foolish acts . . . against which civilization has built a thousand buffers."

Accordingly, when you enter a National Forest Wilderness you must expect no piped water, no prepared shelters, no toilet facilities, no table on which to eat your meals, and no grill to hold your cooking utensils. There will be few trail signs to guide you, so you must know how to use a compass and read a map. You will be on your own in a sometimes alien and unfamiliar environment. You must be prepared to meet the unexpected and overcome the dangers.

In God's wilderness lies the hope of the world — the great fresh, unblighted, unredeemed wilderness. The galling harness of civilization drops off, and the wounds heal ere we are aware. —John Muir (1838-1914)

EARLY YEARS

A nostalgia for the primitive life swept the Nation as the frontier receded. President Theodore Roosevelt and famed historian Frederick Jackson Turner were leading apostles of what came to be known as a wilderness cult. Turner claimed, "Out of his wilderness, out of the freedom of his opportunities, the American fashioned a formula for social regeneration." He added that the American was a higher type of person because he had struggled with and conquered the frontier.

President Roosevelt agreed with Turner. "As our civilization grows older and more complex," he wrote, "we need a greater and not a less development of the fundamental frontier virtues." No one pushed for preservation of the wilderness with greater fervor than Roosevelt, to whom wilderness meant not vistas of esthetic delight, but places to act as a frontiersman. The fact that these reserves, some of which he created with wonderful foresight when he was President, were difficult of access and could be of use to only a small number of people, did not bother him. He was thinking of their value to future generations.

At about this time, the preservationist movement was joined by a group who were not interested in bolstering the manly virtues, but who saw the mountains as living examples of Thoreau's teaching that "In wildness is the preservation of the world." Thoreau and his late 19th century followers, such as John Muir, were free spirits to whom the mountains and rivers and glaciers became a religion. Muir, in 1892, founded the Sierra Club, which was dedicated to "exploring, enjoying and rendering accessible the mountain regions of the Pacific Coast."

A new breed of practical romanticists appeared during the first half of the 20th century. Among them were professional foresters Aldo Leopold and Robert Marshall, men who were cast in the mold of Muir and Thoreau, but who had a more practical sense of social need. Leopold believed that the frontier had a beneficial moral and psychological impact on our Nation. "Many of the attributes most distinctive of Americans," he said, "are due to the impress of wilderness and the life that accompanied it." A man of many accomplishments, probably his most important achievement was to influence his superiors in the Forest Service to acquaint themselves first hand with the wilderness conditions that have helped shape our culture.

While responsible for recreation programs on the National Forests, Robert Marshall was largely instrumental for adoption of the regulation which restricts roads, settlements, and economic development on about 14 million acres of National Forest lands. In 1932, Marshall organized the Wilderness Society which became an articulate and leading clearinghouse and voice for the supporters of wilderness recognition. It later played a major role in getting the Wilderness Act passed by Congress in 1964—a landmark in our conservation history.

|

| Canoeing in Lac La Croix, Boundary Waters Canoe Area, Superior National Forest, Minnesota C-19 |

FIRST WILDERNESS ESTABLISHED

Studies of wildlands on the National Forests began early in the 1920's. In 1924, with the general authorities granted by the 1897 Organic Act under which the National Forests are still being administered, a large part of the land that is now the Gila Wilderness in New Mexico was set aside as a special area for the preservation of wilderness. The Gila, the Nation's first designated Wilderness, now contains 434,000 acres of primitive American lands astride the Mogollon and Diablo mountain ranges. From that year forward, until their authority was superseded by the Wilderness Act of 1964, the Chief of the Forest Service and the Secretary of Agriculture have set aside portions of other National Forests for such protection.

The wilderness idea was taking root and spreading. In 1926, the Superior National Forest Primitive Area in Minnesota was given special status. Later, this became the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, renowned as a roadless and primitive retreat offering canoeing, fishing, and a voyageur experience.

FURTHER PROTECTION

In 1929, the first specific procedures by which the Chief of the Forest Service could designate Primitive Areas were spelled out by the Secretary of Agriculture. These administrative regulations were refined and strengthened in 1939. The additional regulations provided that the Secretary, on the recommendation of the Forest Service, could designate unbroken tracts of 100,000 acres or more as "Wilderness Areas." Areas of 5,000 to 100,000 acres could be designated as "Wild Areas" by the Chief of the Forest Service. Commercial timber cutting, roads, hotels, stores, resorts, summer homes, camps, hunting and fishing lodges, motorboats, and airplane landings were prohibited. Mineral exploration and development was permitted under supervision of the Forest Service.

Under these regulations, public hearings were required before the establishment, modification, or elimination of any Wilderness. Public hearings also were held in order to reclassify Primitive Areas to give them the added protection of Wilderness or Wild status. In advance of such hearings, the Forest Service was required to conduct a complete review of the Primitive Areas to be considered. Prior to 1964, 31 areas were changed to Wilderness or Wild status and another 22 Wilderness and Wild Areas were established on National Forest land which had never been designated as Primitive Areas. The Boundary Waters Canoe Area continued in that category.

Conservation is the foresighted utilization, preservation and/or renewal of forests, waters, lands and minerals, for the greatest good of the greatest number for the longest time. —Gifford Pinchot (1865-1946)

MULTIPLE USE AND SUSTAINED YIELD

In its passing of the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act of 1960, Congress set another milestone in the conservation of the Nation's natural resources. Through that law, Congress redefined the functions of the National Forests to properly and legally encompass all of their uses in the context of modern needs. The legislation stated plainly that: "The establishment and maintenance of areas of wilderness are consistent with the purposes and provisions of this Act."

The Multiple Use Act emphasized anew Gifford Pinchot's concept of the unity of orderly integrated resource management. It recognized that wilderness management is part of forestry and is a compatible and complementary function of all other fitting uses of the land. Congress, by this action, made it clear that wilderness can no longer be considered to serve only a single use. It provides a habitat for wildlife, opportunities for hunting, fishing, scientific research, exercise and other enjoyment of the outdoors.

A total of 88 areas in 75 National Forests in 14 separate States have some form of wilderness protection. These include the following:

| TYPE | NUMBER | ACRES |

| Wilderness | 60 | 9,925,352 |

| Primitive | 28 | 4,363,954 |

| TOTAL | 88 | 14,289,306 |

These 14.2 million acres represent about 8 percent of the entire National Forest System.

There are those who believe that some of these lands should be committed to another type use—such as the growing of timber for harvest.

About one quarter of the Nation's timber supply is obtained from the National Forests. This figure has been increasing steadily. About half of the National Forests are capable of yielding commercial timber crops. These timber lands, too, are a part of our wilderness heritage, and it is only proper that some of them should be retained in the Wilderness System. Therefore, about 6 million acres of productive forest land is now included in National Forest Wilderness or Primitive Areas. This is 40 percent of the National Forest Wilderness. For example, the recently designated Mt. Jefferson Wilderness in Oregon contains about 1.35 billion board feet of quality commercial timber, which will provide a living outdoor laboratory for future environmental studies as well as esthetic and recreational values.

There are also some who think that it is disproportionate to have nearly 8 percent of the National Forests in wilderness that is visited by only 2 or 3 percent of those who come to the National Forests for recreation. However, a great many visitors who do not visit wilderness actually depend upon it in one way or another as a great natural backdrop for their outdoor experiences. No one can view a wilderness without being affected by its vastness of space and scenic beauty where elk, bear, antelope, mountain goat, mountain sheep, and wolves find a refuge from civilization.

|

| Big Horn sheep (top) and Mule Deer (bottom) F-519728-519724 |

THE WILDERNESS ACT OF 1964

The legislation had been passed by Congress, and on September 3, 1964, the President signed it into law.

It was a clear-cut victory for the proponents of wilderness, coming after 8 years of discussion and debate by the Senate and House of Representatives and 18 separate public hearings conducted by Congressional committees in Washington and other cities. The Act represented more of a beginning than a conclusion because it established a new set of governmental processes for designating and managing units of the National Wilderness Preservation System.

Americans have learned to harness the forces of Nature to serve our material needs. We have learned how to cultivate and to utilize Nature through forestry, farming, animal husbandry, and the science of wildlife management that assures outdoorsmen of the good hunt. We have learned the delights of transplanting the essence of Nature into our homes and everyday lives through gardening, whether in the form of a window box, potted plant, or flower bed.

We also have learned the place and purpose of raw and untamed Nature— as a practical, useful land resource, as a provider of exercise to the body and stimulus to the mind, and as a fountain of sustenance and renewal to the soul.

|

| Superstition Mountains in the Superstition Wilderness, Tonto National Forest, Arizona |

The Wilderness Act stands as an affirmation of America's faith in its destiny and of man's belief in himself as a creature of intellect.

It directs and challenges three Federal Agencies—Forest Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, and National Park Service—and the two departments, Agriculture and Interior, of which they are a part, to interpret the mandate of Congress and to fulfill their responsibilities with vision and skill.

It challenges the Congress itself, for the Act provides that future additions to the System may be made only by Congress. The decision to designate wilderness, or not to, is reserved to Congress, as spokesman for the public will.

Above all, the Act challenges the people. Its finest feature is that it provides for public participation and understanding. Before additions, deletions, or changes are made, they must be aired before the people, and the people must be heard. If the ultimate decision in each case, whatever it may be, is based on active interest and involvement of knowledgeable Americans, this in itself represents an achievement in the process of democracy.

The Forest Service is proud of the part it has played in protection of a large amount of wilderness resource in the public behalf for many decades and in administering all of the original 54 components of the National Wilderness Preservation system. It welcomes the interest of more people in wilderness and the opportunity to explain how the Act works and how decisions are made to carry out its provisions.

The wilderness concept is subject to diverse interpretations and conflicts. These are reflected in the Act, an offspring of the democratic process, and are written not in the words of a single-minded, uncompromising individual but in the phrases evolved by Congress during its long consideration and debate of the issues.

|

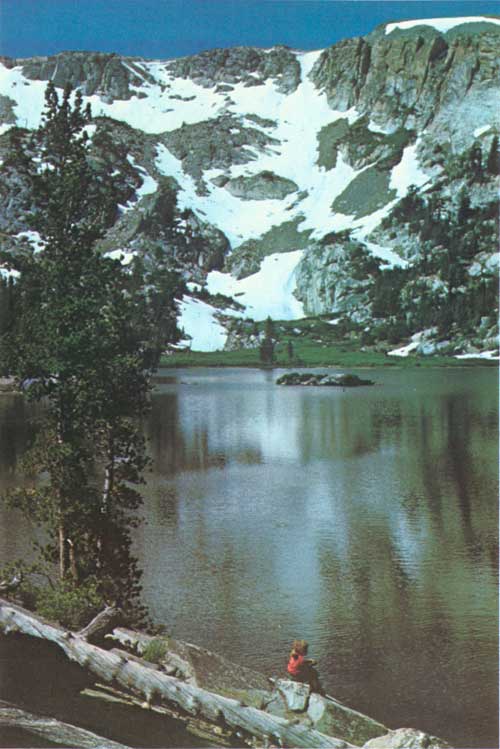

| Snow shoeing in the High Country, Wenatchee National Forest, Washington F-519726 |

The dominant theme and intent of the Wilderness Act is to insure an enduring resource of wilderness for the Nation.

For the Forest Service, this means that protection and advancement of wilderness values must be given priority in many decisions that are made day by day, week by week, year by year.

It means that such "non-conforming uses" as the Act authorized must be conducted in such a manner that they have only a minimum effect on the wilderness resource. The Act lists a series of special provisions for such uses, directing that rules governing them must be "reasonable"; however, administrators also must manage each area in a manner "to preserve its wilderness character."

The Forest Service was given its guidelines by the Secretary of Agriculture on June 1, 1966, when he issued regulations on the operation of the National Forest units of the National Wilderness Preservation System under its charge.

The Secretary directed the Forest Service to prepare an individual plan for each of the original 54 Wildernesses incorporated into the System, and for the others to follow. He noted that because each Wilderness has its own separate characteristics, a rigid set of rules would be impossible; however, based on terms of the Act, he defined the basic guiding principle as follows:

"National Forest Wilderness resources shall be managed to promote, perpetuate, and, where necessary, to restore the wilderness character of the land and its specific values of solitude, physical and mental challenge, scientific study, inspiration, and primitive recreation."

"Toward that end," wrote the Secretary, "National Forest administrators must adhere to three objectives:

"Natural ecological succession will be allowed to operate freely, to the extent feasible.

"Wilderness will be made available for human use to the optimum extent consistent with maintenance of primitive conditions.

"Where conflicts arise, wilderness values will be dominant to the extent not limited by the Law or by regulations."

What are the non-conforming uses permitted by the Act and Forest Service management regulations bearing on them?

MINING

The continuation of prospecting for minerals is authorized, but it must be conducted in a manner as compatible as possible with preservation of the Wilderness environment. Accordingly, except in unusual circumstances, only primitive transportation (horse, mule, burro, or backpacking) can be used. Motorized vehicles are permitted only when their prohibition would be unreasonable.

Patents issued under the mining laws for claims filed after the Act convey title to mineral deposits but not to the land—title to the surface remaining with the Government.

The laws pertaining to mining and mineral leasing shall extend to Wilderness until 1983. Subject to reasonable regulations governing ingress and egress, persons or firms with valid mining claims may engage in exploration, drilling, and production activities including, where essential, the use of mechanized ground and air equipment. The Forest Service recognizes about 4,800 mining claims in Wilderness Areas and the right to conduct explorations on them.

In regard to mining activities that occur on claims after an area is included in the Wilderness System—if an application for patent is not pending—the claimant is now required to remove improvements no longer needed for mining, to restore the contour of the land as nearly as practicable, and to promote its revegetation by natural means. Permits for access to valid claims prescribe routes and modes of travel, and other necessary conditions which will result in the least possible impact on the wilderness resource. No claimant can construct roads within a Wilderness without authorization and filing of a plan.

All mineral leases, permits, and licenses must contain reasonable stipulations for protection of the wilderness resource, consistent with its use in mining. Claimants must take measures, such as the use of settling ponds and disposition of mineral tailings and dumpage, as directed by the Forest Service to prevent pollution, siltation, or deterioration of lands, streams, and lakes. Timber may be cut only for mining purposes and in a way to minimize soil movement, damage from water runoff, and adverse effect on the wilderness character of the land.

Except for valid rights existing at the end of 1983, National Forest Wilderness then will be withdrawn from use under the mining laws.

|

| Eastern Forest F-518478-A |

LIVESTOCK

Domestic livestock use established prior to the effective date of the Act shall be continued consistent with reasonable regulation by the Secretary and with the objective of maintenance or improvement of soil, cover vegetation, and wilderness values. Maintenance, reconstruction, or relocation of existing livestock management improvements and structures will be permitted. Additional facilities may be installed when necessary so as to protect or enhance wilderness values.

Domestic livestock losses resulting from carnivorous animals (coyotes, bears, mountain lions, etc.) will be resolved on a case-by-case basis. An effort will be made to control the individual offending animal with the least possible hazard to humans or other animals in the area.

|

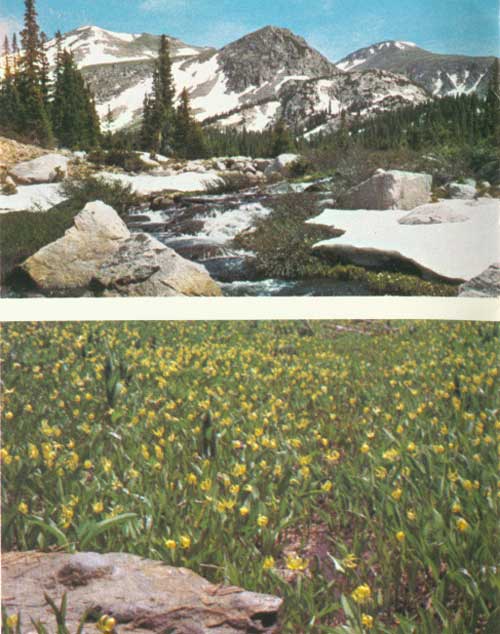

| Rawah Wilderness (top) in the Roosevelt National Forest, Colorado F-519735 Erythronium Grandiflorium (Glacier Lily) (bottom) in the Mission Mountains Primitive Area, Flathead National Forest, Montana F-519727 |

WATER RESOURCES

The President has the power to authorize prospecting for water resources, establishment and maintenance of reservoirs, water-conservation works, power projects, transmission lines, and other facilities if he determines that such uses will better serve the public interest than will their denial.

Solitude is as needful to the imagination as society is wholesome for the character. —James Russell Lowell (1819-1891)

RECREATION

In a Wilderness, Man is only a visitor.

The Wilderness is for his use and enjoyment, but he has an obligation to leave this Wilderness unimpaired for future generations to know and enjoy. The achievement of such an objective represents one of the keenest challenges implicit in the Wilderness Act.

The administrator is challenged to devise and practice new skills so as to manage Wildernesses as a basic resource.

The public is challenged to understand and appreciate the problems, as well as the pleasures, of a wilderness adventure and, by so doing, to fulfill its responsibility in protecting the resource it prizes.

For many years the Forest Service has encouraged recreational enjoyment of Wilderness. It has laid out trails for hikers, hunters, riders, and others and has published maps to guide them and point out areas of interest. In recent years, it has issued booklets such as "Backpacking in the National Forest Wilderness—A Family Adventure" in order to assist a family group in planning for a safe and pleasant trip. The film "Trail Ride in the Wilderness" demonstrates the values of group trips sponsored by non-profit conservation and outdoor organizations. Forest supervisors and rangers cooperate with packers and outfitters so as to better understand their problems and to assure that their services will be consistent with wilderness values.

Until recent times, wilderness required little management because it was little used. But with a continual acceleration in use, the same forces that made the Wilderness Act necessary demand the application of great wisdom to prevent its deterioration.

From a photograph of the Maroon Bells, Maroon Bells Snowmass

Wilderness, White River National Forest, Colorado

Ours is a fast-growing, fast-changing Nation. Centers of population are shifting. The surge to the outdoors, reflecting the affinity of Americans with Nature, is unending. Thus, the modes of a Daniel Boone or a Jim Bridger, who cut their beds of spruce boughs, built lean-tos and tables of poles, made "dead-falls" and exercised other freedoms with native materials, cannot be tolerated by those who would follow in their footsteps. Man's actions now must be disciplined so that Nature may be free.

In the high wilderness country, soils are fragile, covered by delicate plants and shrubs. Overuse and misuse by visitors in this environment can prove to be as damaging to watershed and wilderness values as would the bulldozer, or the careless logger and the miner.

Year after year, National Forest administrators have considered these problems with an increasing degree of urgency.

Some wilderness enthusiasts are inclined to regard the land in terms of their particular interests, whether it be hunting, hiking, or some other form of recreation. They may find disappointment ahead, for the Act transcends all selfish interests. It directs the Forest Service to manage wilderness as a resource, in which naturalness is perpetuated.

Wilderness is part and parcel of democracy—of the heritage, of the progress, of the expression of America that touches the mind, heart, and soul of each individual in a special way known only to himself.

In this Nation, Wilderness now belongs to tomorrow and to tomorrow's tomorrow. One generation hence, one century hence, one thousand years hence, a thoughtful American community may decree for Wilderness an altogether different role.

Our successors are entitled to that choice!

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

PA-942/sec1.htm Last Updated: 12-Sep-2011 |