A PRIMER OF FORESTRY

PART I—THE FOREST

|

|

CHAPTER II.

TREES IN THE FOREST.

The nature of a tree, as shown by its behavior in the forest, is

called its silvicultural character. It is made up of all those qualities

upon which the species as a whole, and every individual tree, depends in

its struggle for existence. The regions in which a tree will live, and

the places where it will flourish best; the trees it will grow with, and

those which it kills or is killed by; its abundance or scarcity; its

size and rate of growth—all these things are decided by the inborn

qualities, or silvicultural character, of each particular kind of

tree.

|

|

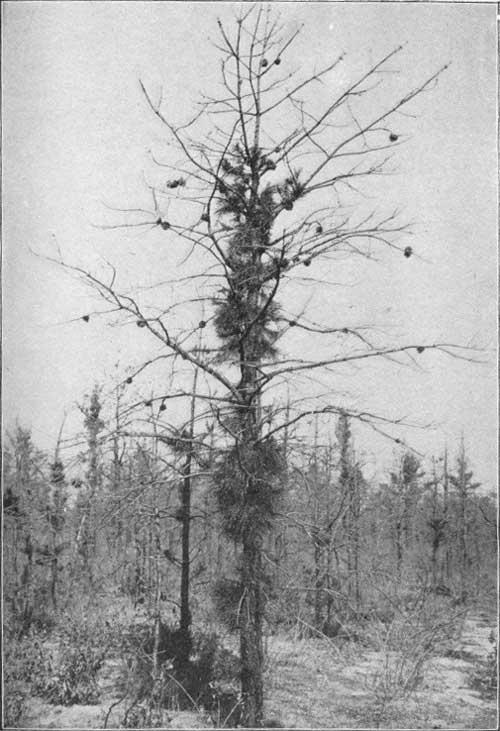

Plate XI. BLACK SPRUCE ON THE HAMILTON RIVER, LABRADOR, NEAR THE

NORTHERN LIMIT OF TREE GROWTH.

|

THE VARIOUS REQUIREMENTS OF TREES.

Different species of trees, like different races of men, have special

requirements for the things upon which their life depends. Some races,

like the Eskimos, live only in cold regions. (See Pl. XI.) Others, like

the South Sea Islanders, must have a very warm climate to be

comfortable, and are short-lived in any other. (See fig. 23.) So it is

with trees, except that their different needs are even more varied and

distinct. Some of them, like the Willows, Birches, and Spruces of

northern Canada, stand on the boundary of tree growth within the Arctic

Circle. Other species grow only in tropical lands, and can not resist

even the lightest frost. (See Pl. XII.) It is always the highest and

lowest temperature, rather than the average, which decides where a tree

will or will not grow. Thus the average temperature of an island where

it never freezes may be only 60°, while another place, with an

average of 70°, may have occasional frosts. Trees which could not

live at all in the second of these places, on account of the frost,

might flourish in the lower average warmth of the first.

|

|

Fig. 23.—A forest of Palms in southern Florida.

|

In this way the bearing of trees toward heat and cold has a great

deal to do with their distribution over the surface of the whole earth.

Their distribution within shorter distances also often depends largely

upon it. In the United States, for example, the Live Oak does not grow

in Maine, nor the Canoe Birch in Florida. Even the opposite sides of the

same hill may be covered with two different species, because one of them

resists the late and early frosts and the fierce midday heat of summer,

while the other requires the coolness and moisture of the northern

slope. (See fig. 24.) On eastern slopes, where the sun strikes early in

the day, frosts in the spring and fall are far more apt to kill the

young trees, or the blossoms and twigs of older ones, than on those

which face to the west and north, where growth begins later in the

spring, and where rapid thawing, which does more harm than the freezing

itself, is less likely to take place.

|

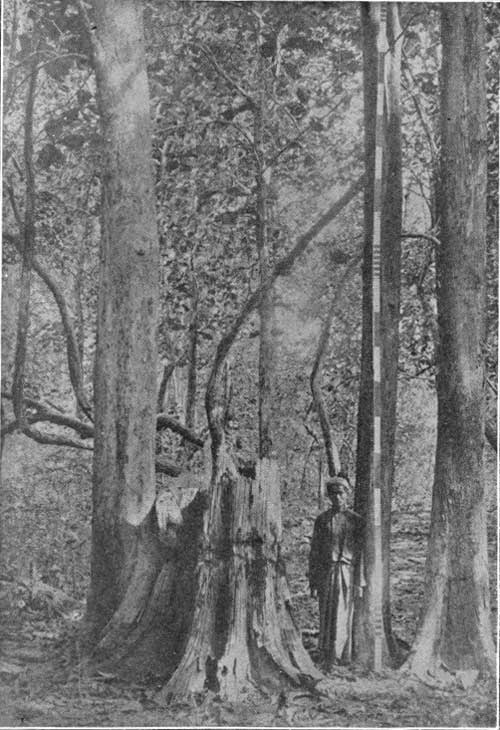

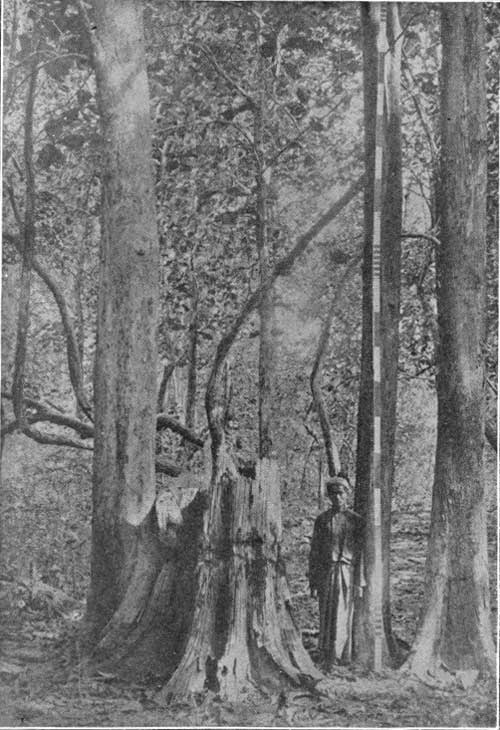

Plate XII. A TEAK FOREST IN BRITISH INDIA.

The Teak tree yields one of the most durable and valuable kinds of

timber, especially adapted to shipbuilding, but it will not grow where

there is the slightest frost. Its durability is shown by the condition

of the old stump, from which the large tree on the left grew as a

sprout.

|

|

|

Fig. 27.—Light crown of an intolerant tree, the Western Larch. The

tree with heavy foliage and horizontal branches in the background to the

left is a Western White Pine, a tolerant species. Northern Idaho.

|

REQUIREMENTS OF TREES FOR HEAT AND MOISTURE.

Heat and moisture act together upon trees in such a way that it is

sometimes hard to distinguish their effects. A dry country, or a dry

slope, is apt to be hot as well, while a cool northern slope is almost

always moister than one turned toward the south. Still the results of

the demand of trees for water can usually be distinguished from the

results of their need of warmth, and it is found that moisture has

almost as great an influence on the distribution of trees over the earth

as heat itself. Indeed, within any given region it is apt to be much

more conspicuous, and the smaller the region the more noticeable often

is its effect, because the contrast is more striking. Thus it is

frequently easy to see the difference between the trees in a swamp and

those on a dry hillside near by, when it would be far less easy to

distinguish the general character of the forest which includes both

swamp and hillside from that of another forest at a distance. (See fig.

25.) In many instances the demand for water controls distribution

altogether. For this reason the forests on the opposite sides of

mountain ranges are often composed of entirely different trees. On the

west slope of the Sierra Nevada of California, for example, where there

is plenty of moisture, there is also one of the most beautifull of all

forests. (See fig. 26 and Pl. XIII.) The east slope, on the contrary,

has almost no trees, because its rainfall is very slight, and those

which do grow there are small and stunted in comparison with the giants

on the west. (See Pl. XIV.) Again, certain trees, like the Bald Cypress

and the River Birch, grow only in very moist land; others, like the

Mesquite and the Pinyon or Nut Pine, only on the driest soils; while

still others, like the Red Cedar and the Red Fir, seem to adapt

themselves to almost any degree of moisture, and are found on very wet

and very dry soils alike. In this way the different demands for moisture

often separate the kinds of trees which grow in the bottom of a valley

from those along its slopes, or even those in the gullies of hillsides

from those on the rolling land between. (See Pl. XV.) A mound not more

than a foot above the level of a swamp is often covered with trees

entirely different from those of the wetter lower land about it.

|

|

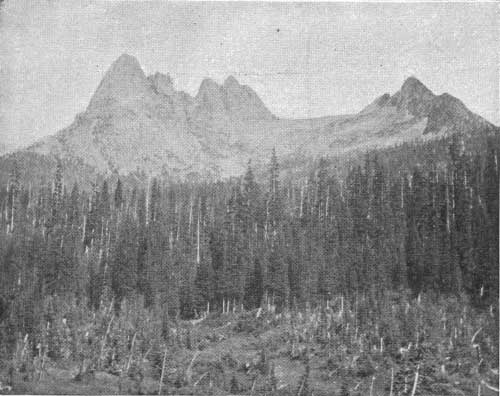

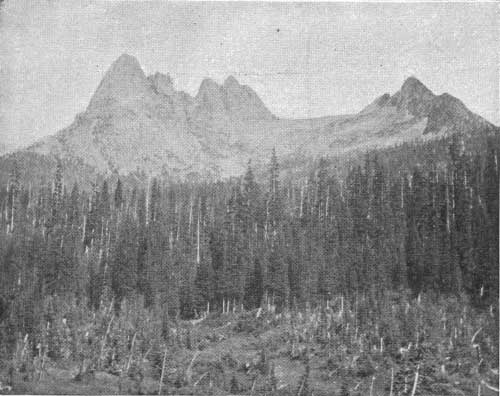

Fig. 24.—The Black Hemlock in its home. Cascade Mountains of

Washington.

|

|

|

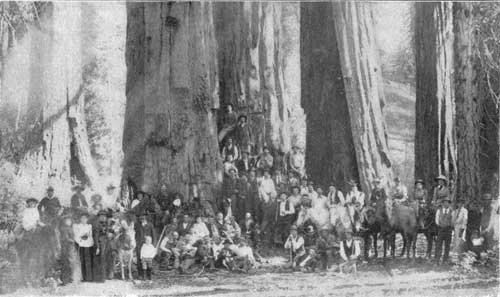

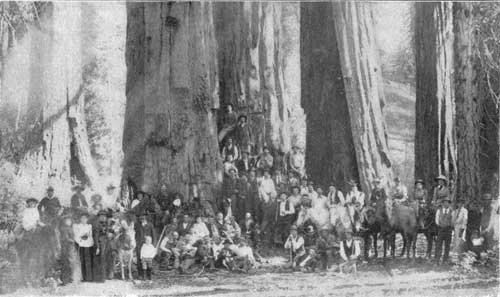

Plate XIII. FOREST ON THE WESTERN SLOPES OF THE SIERRA NEVADA.

CALIFORNIA. This Sierra forest is one of the richest and most beautiful

of all woodlands. It contains the great Sequoia, massive and imposing

beyond all other trees, and the graceful Sugar Pine, the largest and

among the most useful of Pines. The large trees in the middle of the

picture are Sequoias.

|

|

|

Fig. 25.—Cypress in a hollow. Pine on the slightly higher land near

by. Wet weather spring, Southern Georgia.

|

|

|

Fig. 26.—Dense forest in a region of great rainfall. Olympic

Peninsula, Washington.

|

Such matters as these have far more to do with the places in which

different trees grow than the chemical composition of the soil. But its

mechanical nature—that is, whether it is stiff or loose, fine or

coarse in grain, deep or shallow—is very important, because it is

directly connected with heat and moisture and the life of the roots in

the soil.

|

|

Plate XIV. A REGION OF LITTLE RAIN. COLORADO.

|

|

|

Fig. 28.—Heavy crowns of a tolerant species. The Alpine Fir in

northern Washington.

|

|

|

Fig. 29.—A small Red Spruce in the Adirondack Mountains of New

York. For many years this tree stood under the dense cover of taller

trees. During that time its branches spread to the sides, but it made

scarcely any growth in height. Then more light came to it, probably by

the fall of some tall neighbor, and it began to recover its strength and

grow much faster. The thin upper part of line crown is where this faster

height growth has been going on.

|

REQUIREMENTS OF TREES FOR LIGHT.

The relations of trees to heat and moisture are thus largely

responsible for their distribution upon the great divisions of the

earth's surface, such as continents and mountain ranges, as well as over

the smaller rises and depressions of every region where trees grow. But

while heat and moisture decide where the different kinds of trees can

grow, their influence has comparatively little to do with the struggles

of individuals or species against each other for the actual possession

of the ground. The outcome of these struggles depends less on heat and

moisture than on the possession of certain qualities, among which is the

ability to bear shade. With regard to this power trees are roughly

divided into two classes, often called shade-bearing and

light-demanding, following the German, but better named tolerant and

intolerant of shade. (See figs. 27, 28.) Tolerant trees are those which

flourish under more or less heavy shade in early youth; intolerant trees

are those which demand a comparatively slight cover, or even

unrestricted light. Later in life all trees require much more light than

at first, and usually those of both classes can live to old age only

when they are altogether unshaded from above. But there is always this

difference between them: the leaves of tolerant trees will bear more

shade. Consequently those on the lower and inner parts of the crown are

more vigorous, plentiful, and persistent than is the case with

intolerant trees. Thus the crown of a tolerant tree in the forest is

usually denser and longer than that of one which bears less shade. It is

usually true that the seedlings of trees with dense crowns are able to

flourish under cover, while those of light-crowned trees are intolerant.

This rough general rule is often of use in the study of forests in a new

country, or of trees whose silvicultural character is not known.

|

|

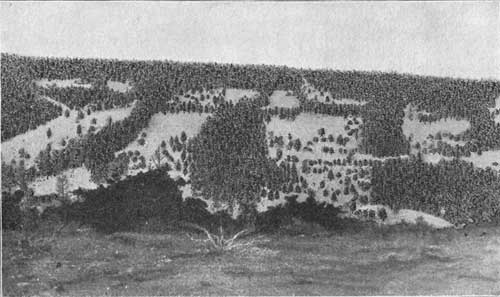

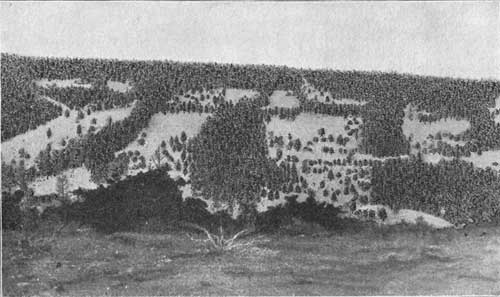

Plate XV. FOREST-FILLED GULLIES ON THE EAST SLOPE OF THE CASCADE RANGE.

OREGON.

|

|

|

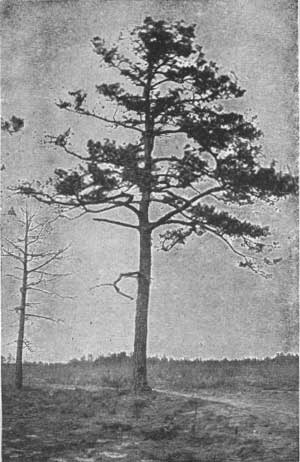

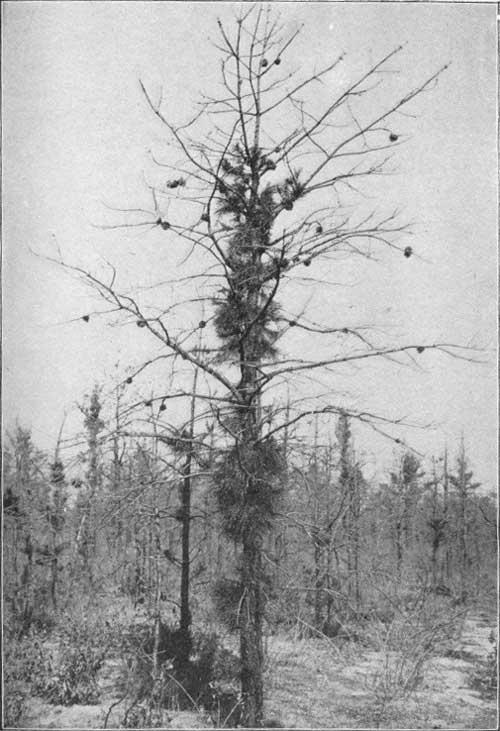

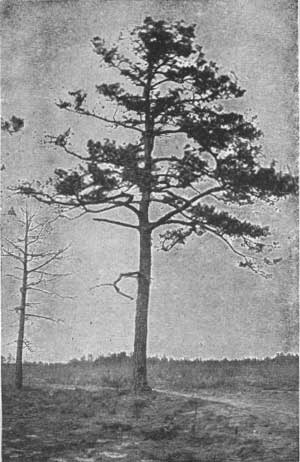

Fig. 30.—A Pitch Pine, producing seed abundantly, as shown by the

numerous cones, but with no seedlings beneath it. Fire has run over the

ground, and the surface is very dry. A strong breeze was blowing when

the picture was taken. New Jersey.

|

TOLERANCE AND INTOLERANCE.

The tolerance or intolerance of trees is one of their most important

silvicultural characters. Frequently it is the first thing a forester

seeks to learn about them, because what he can safely undertake in the

woods depends so largely upon it. Thus tolerant trees will often grow

vigorously under the shade of light-crowned trees above them, while if

the positions were reversed the latter would speedily die. (See Pl.

XVI.) The proportion of different kinds of trees in a forest often

depends on their tolerance. Thus Hemlock sometimes replaces White Pine

in Pennsylvania, because it can grow beneath the Pine, and so be ready

to fill the opening whenever a Pine dies. But the Pine can not grow

under the Hemlock, and can only take possession of the ground when a

fire or a windfall makes an opening where it can have plenty of light.

Some trees, after being over-shaded, can never recover their vigor when

at last they are set free. Others do recover and grow vigorously even

after many years of starving under heavy shade. The Red Spruce, in the

Adirondacks, has a wonderful power of this kind, and makes a fine tree

after spending the first fifty or even one hundred years of its life in

reaching a diameter of a couple of inches. (See fig. 29.)

|

|

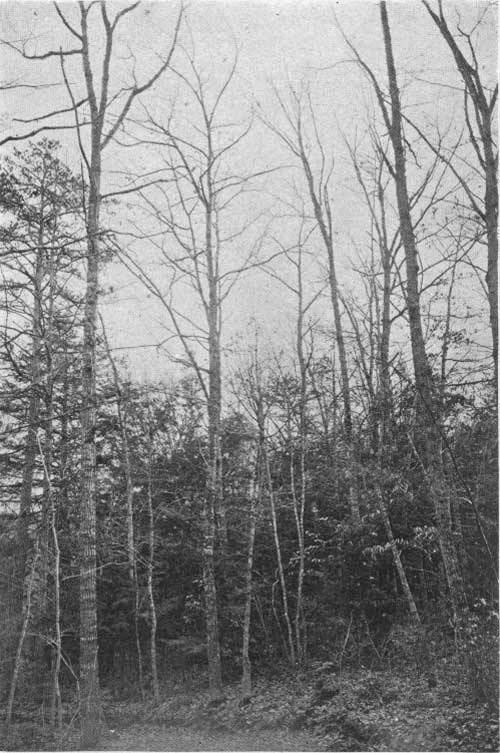

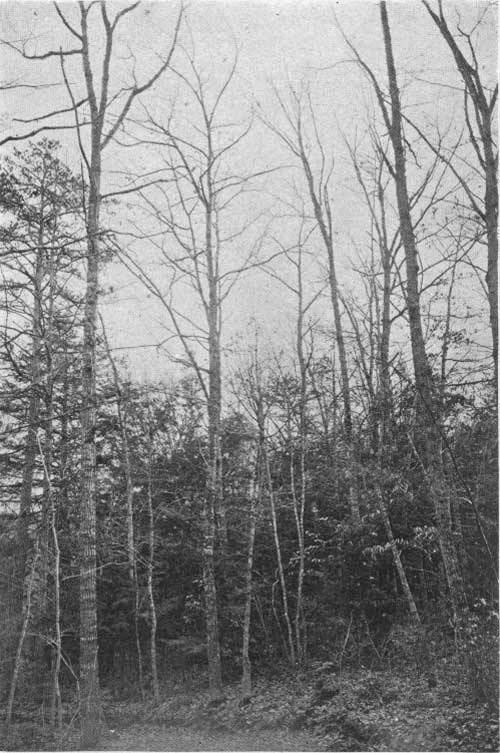

Plate XVI. A GROUP OF HEMLOCKS AND RHODODENDRONS GROWING IN THE SHADE OF

OAKS AND CHESTNUTS. MILFORD, Pa.

|

|

|

Fig. 31.—Winged seeds: 1, Basswood; 2, Boxelder; 3, Elm; 4, Fir; 5

to 8, Pine.

|

|

|

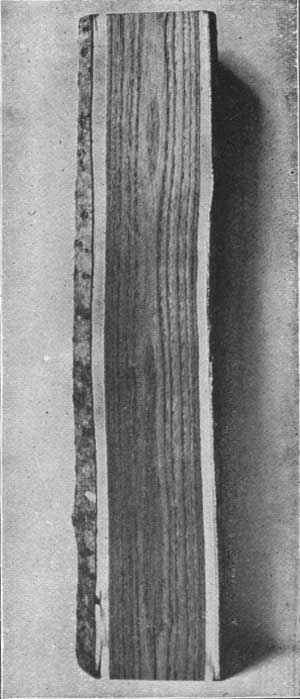

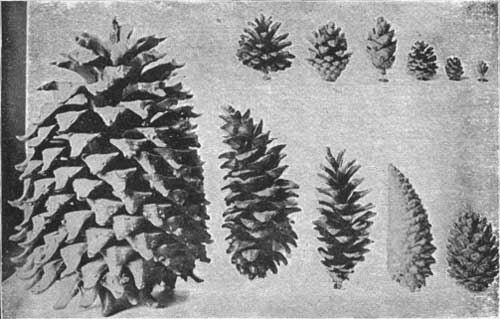

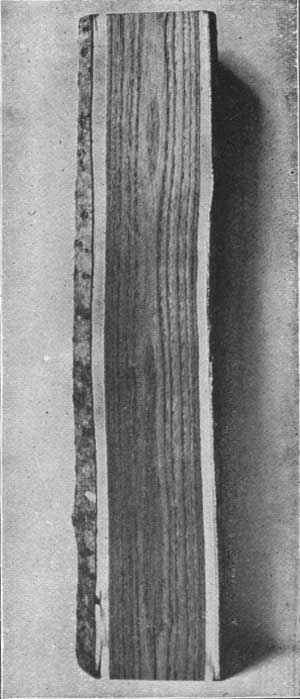

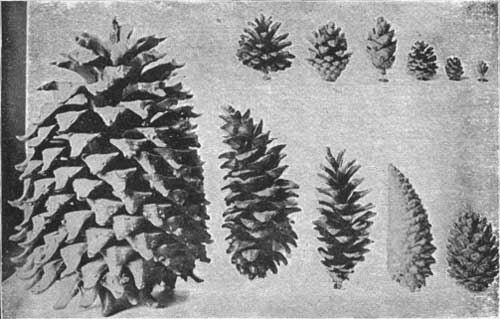

Fig. 32.—Cones: Beginning at the left, these cones come from

Coulter's Pine, the western White Pine, the Eastern White Pine, the

Knob-Cone Pine, the Fox-Tail Pine, the Pitch Pine, the Lodgepole Pine,

the Red Fir, the Shortleaf Pine, the Eastern Hemlock, and the Eastern

Arbor Vitæ.

|

|

|

Fig. 33.—Young Oaks starting under an old forest of Pines. Eastern

North Carolina.

|

The relation of a tree to light changes not only with its age, but

also with the place where it is growing, and with its health. An

intolerant tree will stand more cover where the light is intense than in

a cloudy northern region, and more if it has plenty of water than with a

scanty supply. Vigorous seedlings will get along with less light than

sickly ones. Seedlings of the same species will prosper under heavier

shade if they have always grown under cover than if they have had plenty

of light at first and have been deprived of it afterwards.

|

|

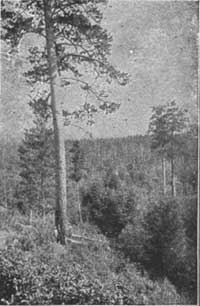

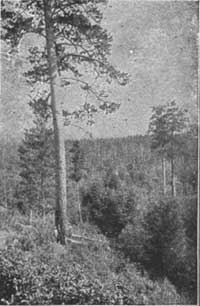

Fig. 34.—Pure forest of Western Yellow Pine in the Black Hills of

South Dakota. The trees here are smaller in size than those of Montana

(see fig. 35), but their power of reproduction is much greater.

|

THE RATE OF GROWTH.

|

|

Fig. 35—Western Yellow Pine in mixture with other trees. Flathead

valley, Montana.

|

The rate of growth of different trees often decides which one will

survive in the forest. For example, if two intolerant kinds of trees

should start together on a burned area or an old field, that one which

grew faster in height would overtop the other and destroy it in the end

by cutting off the light. Some trees, like the Black Walnut, grow

rapidly from their earliest youth. Others grow very slowly for the first

few years. The stem of the Longleaf Pine, at 4 years old, is usually not

more than 5 inches in length. During this time the roots have been

growing instead of the stem. The period of its rapid growth in height

comes later.

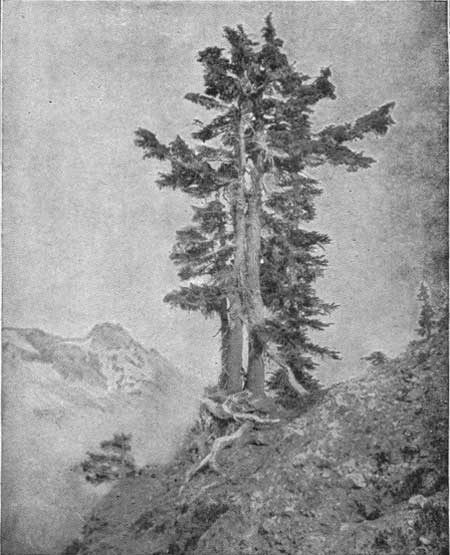

The place where a tree stands has a great influence on its rate of

growth. Thus the trees on a hillside are often much smaller than those

of equal age in the rich hollow below, and those on the upper slopes of

a high mountain are commonly starved and stunted in comparison with the

vigorous forest lower down. (See Pl. XVII.) The Western Chinquapin,

which reaches a height of 150 feet in the coast valleys of northern

California, is a mere shrub at high elevations in the Sierra Nevada. The

same thing often appears in passing from the more temperate regions to

the far north. Thus the Canoe Birch, at its northern limit, rises only a

few inches above the ground, while farther south it becomes a tree

sometimes 120 feet in height.

|

|

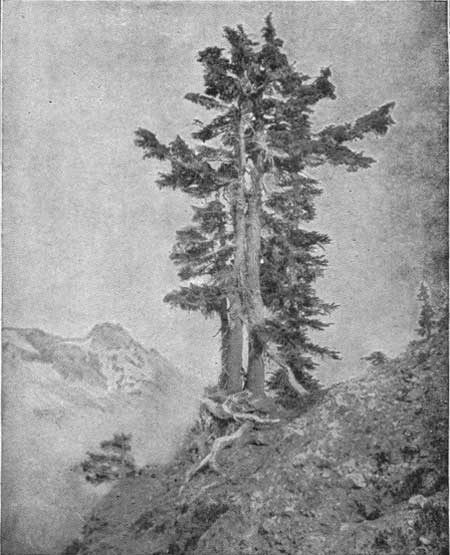

Plate XVII. STUNTED WHITE-BARK PINE AND BLACK HEMLOCK AT TIMBER LINE ON

MOUNT HOOD. OREGON.

|

THE REPRODUCTIVE POWER OF TREES.

|

|

Fig. 36.—Mixed forest of White Pine, Chestnut, and Oak at Milford,

Pa.

|

Another matter which is of the deepest interest to the forester is

the reproductive power of his trees. Except in the case of sprouts and

other growth fed by old roots, this depends first of all on the quantity

of the seed which each tree bears; but so many other considerations

affect the result that a tree which bears seed abundantly may not

reproduce itself very well. (See fig. 30.) A part of the seed is always

unsound, and sometimes much the larger part, as in the case of the Tulip

Tree. But even a great abundance of sound seed does not always insure

good reproduction. The seeds may not find the right surroundings for

successful germination, or the infant trees may perish for want of

water, light, or suitable soil. Where there is a thick layer of dry

leaves or needles on the ground, seedlings often perish in great numbers

because their delicate rootlets can not reach the fertile soil beneath.

The same thing happens when there is no humus at all and the surface is

hard and dry. The weight of the seed also has a powerful influence on

the character of reproduction. Trees with heavy seeds, like Oaks,

Hickories, and Chestnuts, can sow them only in their own neighborhood,

except when they stand on steep hillsides or on the banks of streams, or

when birds and squirrels carry the nuts and acorns to a distance. (See

Pl. XVIII.) Trees with light, winged seeds, like the Poplars, Birches,

and Pines, have in great advantage over the others, because they can

drop their seeds a long way off. (See figs. 31, 32.) The wind is the

means by which this is brought about, and the adaptation of the seeds

themselves is often very curious and interesting. The wing of a Pine

seed, for example, is so placed that the seed whirls when it falls, in

such a way that it falls very slowly. Thus the wind has time to carry it

away before it can reach the ground. In heavy winds Pine and other

winged seeds are blown long distances—sometimes as much as several

miles. This explains how certain kinds of trees, like the Gray Birch and

the White Pine, grow up in the middle of open pastures, and how others,

such as the Lodgepole Pine, cover great areas, far from the parent

trees, with young growth of even age.

|

|

Plate XVIII. A NATURAL AVENUE OF RED CEDARS. NEW JERSEY. The seeds of

these trees were dropped by birds which perched on the fences.

|

THE SUCCESSION OF FOREST TREES.

Such facts help to explain why, in certain places, it happens that

when Pines are cut down Oaks succeed them, or when Oaks are removed

Pines occupy the ground. It is very often true that young trees of one

kind are already growing unnoticed beneath old trees of another, and so

are ready to replace them whenever the upper story is cut away. (See

fig. 33.)

|

|

|

Fig. 37.—Pure forest of White Cedar near Toms River, New Jersey.

|

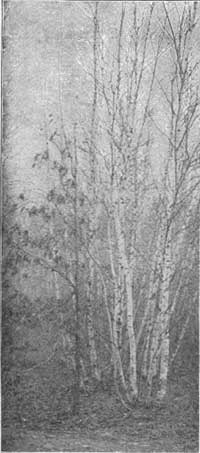

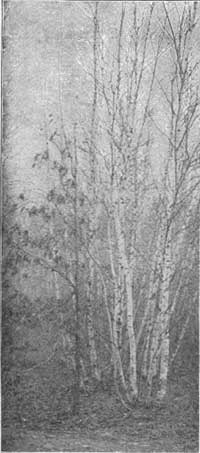

Fig. 38.—Sprouts of Gray Birch with a small White Oak in the

foreground. Milford, Pa.

|

PURE AND MIXED FOREST.

The nature of the seed has much to do with the distribution of trees

in pure or mixed forest. It is the habit of some trees to grow in bodies

of some extent containing only a single kind; in other words, in pure

forest. (See fig. 34 and Pl. XIX.) The Longleaf Pine of the South

Atlantic and Gulf States is of this kind, and so is the Lodgepole Pine

of the West. Conifers are more apt to grow in pure forest than broadleaf

trees, because it is more common for them to have winged seeds. The

greater part of the heavy-seeded trees in the United States are

deciduous, and most of the deciduous trees grow in mixed forest,

although there are some conspicuous exceptions. But even in mixed

forests small groups of trees with heavy seeds are common, because the

young trees naturally start up beneath and around the old ones. A heavy

seed, dropping from the top of a tall tree, often strikes the lower

branches in its fall and bounds far outside the circle of the crown.

Trees which are found only, or most often, in pure forest are the social

or gregarious kinds; those which grow in mixture with other trees are

called scattered kinds. Most of the hardwood forests in the United

States are mixed; and many mixed forests, like that in the Adirondacks,

contain both broadleaf trees and conifers. (See fig. 36 and Pls. XX,

XXI.) The line between gregarious and scattered species is not always

well marked, because it often happens that a tree may be gregarious in

one place, and live with many others elsewhere. The Western Yellow Pine,

which forms, on the plateau of central Arizona, perhaps the largest pure

Pine forest of the earth, is frequently found growing with other species

in the mountains, especially in the Sierra Nevada of central California.

(See figs. 34, 35.)

|

|

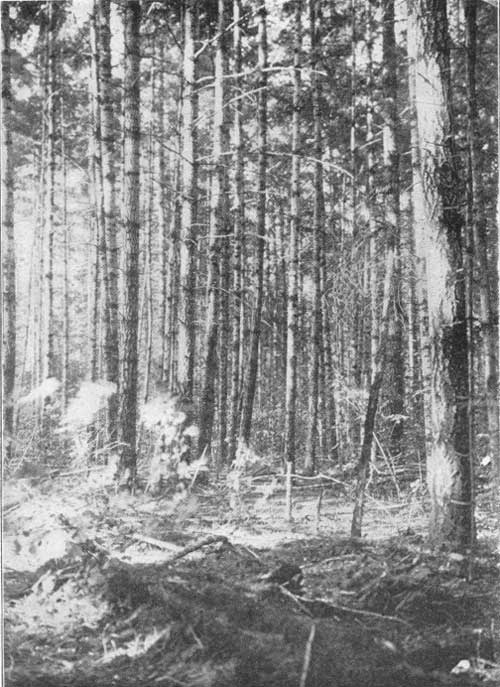

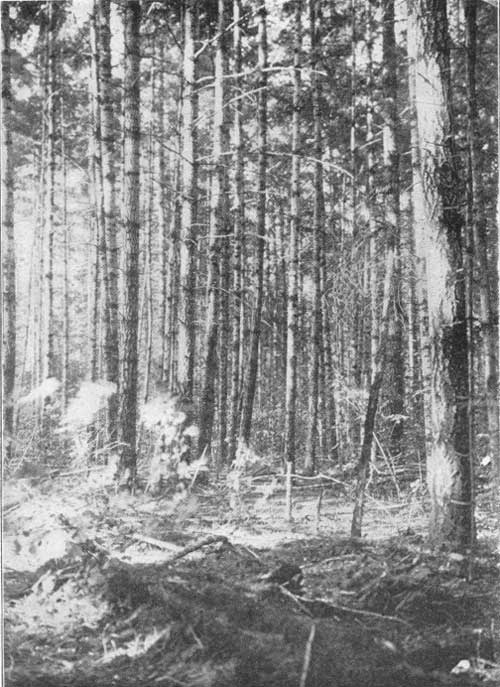

Plate XIX. PURE FOREST OF YOUNG RED FIR. WESTERN OREGON. Except in parts

of Washington and Oregon, the Red Fir is less often found pure than in

mixture with other tress. It is one of the most valuable timber trees of

the world, and is very widely distributed in the Western States. On the

northern part of the Pacific slope it is very abundant and of great

size, and its wood is widely used both at home and abroad, under the

misleading name of Oregon Pine.

|

|

|

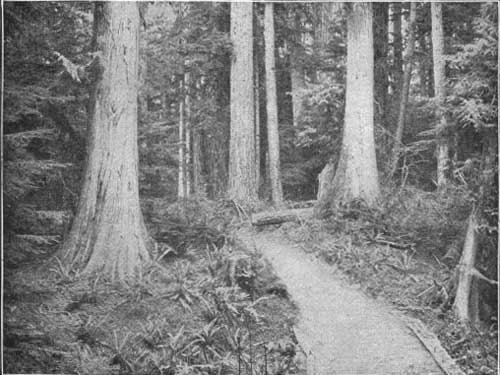

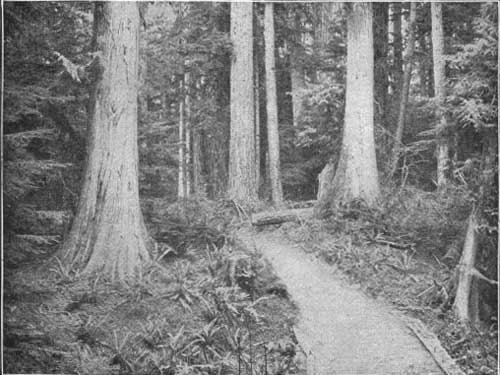

Plate XX. A MIXED FOREST OF CONIFERS ON THE WESTERN SLOPE OF THE CASCADE

RANGE. VALLEY OF CASCADE CREEK, SKAGIT RIVER BASIN, WASHINGTON.

|

|

|

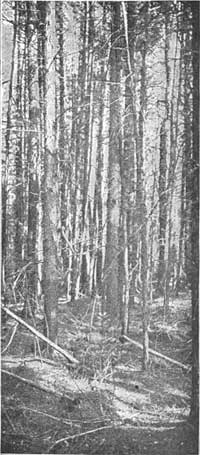

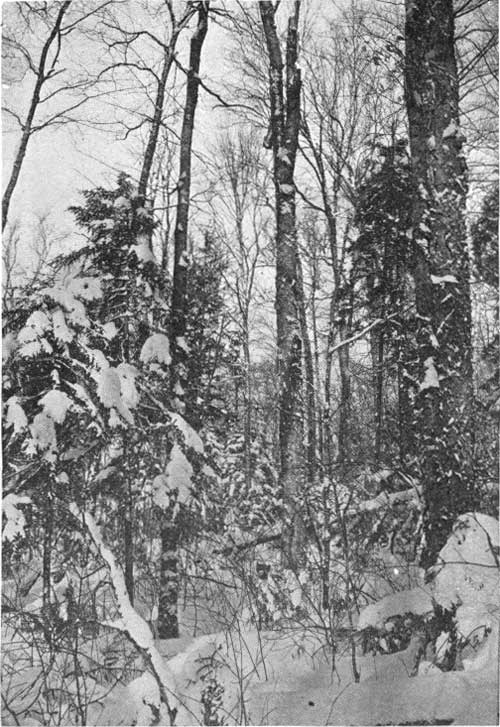

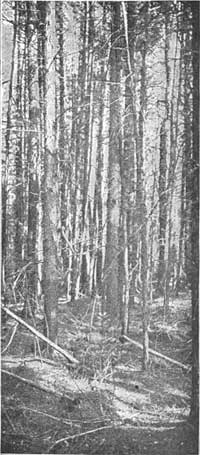

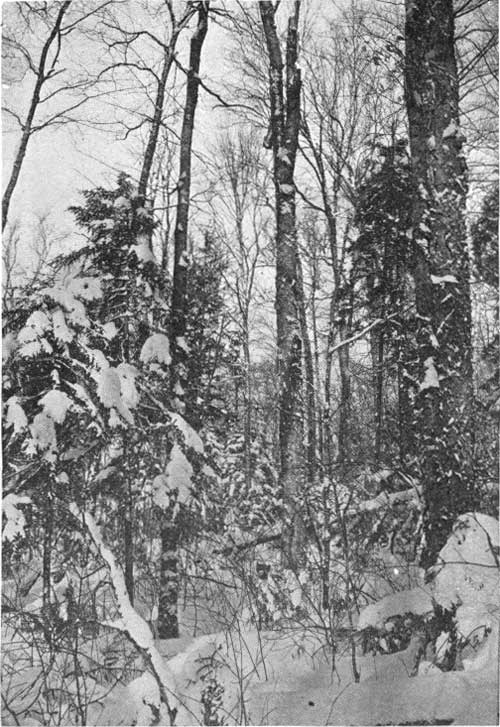

Plate XXI. MIXED FOREST IN THE ADIRONDACK MOUNTAINS, NEW YORK. A GROUP

OF YOUNG SPRUCES UNDER OLDER SPRUCE, BIRCH, AND MAPLE. In the foreground

are many young broadleaf seedlings. The Adirondack forest contains

Beech, Birch, Maple, Cherry, and Poplar among the broadleaf trees, and

Pine, Spruce, Hemlock, Larch, Fir, and Cedar among the cone bearers.

|

|

|

Fig. 39.—Sprouts of Pitch Pine from the neighborhood of Toms River,

New Jersey.

|

Trees which occupy the ground to the exclusion of all others do so

because they succeed better, under the conditions, than their

competitors. (See fig. 37.) It may be that they are able to get on with

less water, or to grow on poorer soil, their rate of growth or power of

reproduction may be greater, or there may be some other reason why they

are better fitted for their surroundings. But the gregarious trees are

not all alike in their ability to sustain themselves in different

situations, while the differences between some of the mixed-forest

species are very marked indeed. Thus Black Walnut, as a rule, grows only

in rich moist soil, and Beech only in damp situations. Fire Cherry, on

the other hand, is most common on lands which have been devastated by

fire, and the Rock Oak is most often found on dry barren ridges. The

Tupelo or Black Gum and the Red Maple both grow best in swamps, but it

is a common thing to find them also on dry stony soils at a distance

from water. The knowledge of such qualities as these is of great

importance in the management of forest lands.

REPRODUCTION BY SPROUTS.

|

|

Fig. 40.—Chestnut sprouts from the stump. Milford, Pa.

|

Besides reproduction from seed, which plays so large a part in the

struggle for the ground, reproduction by sprouts from old roots or

stumps is of great importance in forestry. (See fig. 38.) Trees differ

very much in their power of sprouting. In nearly all conifers except the

California coast Redwood, which has this ability beyond almost every

other tree, it is lacking altogether. The Pitch or Jack Pine of the

Eastern United States has it also to some extent, but in most places the

sprouts usually die in early youth, and seldom make merchantable trees.

(See fig. 39 and Pl. XXII.) In the broadleaf kinds, on the other hand,

it is a general and very valuable quality. Young stumps, as a rule, are

much more productive than old ones, although some prolific species, like

the Chestnut (see fig. 40), sprout plentifully in old age. Other

species, like the Beech, furnish numerous sprouts from young stumps and

very few or none at all from old ones, and still others never sprout

freely even in early youth.

|

|

Plate XXII. SUCKERS, OR SPROUTS, FROM THE TRUNK AND BRANCHES OF A PITCH

PINE. SOUTHERN NEW JERSEY. A year before the picture was taken a forest

fire passed over this place and burned to the top of the tree,

destroying all the needles; yet, the tree was not killed, although

scarcely any other kind could have survived. It put out a vigorous

growth at suckers, and it still has a chance for life. Such examples are

common throughout the burnt parts of southern New Jersey, where large

and vigorous sprouts from the roots of tress of this species which have

keen killed to the ground by fire are very frequent.

|

primer/chap2-1.htm

Last Updated: 06-Jul-2009 |

|