|

A PRIMER OF FORESTRY PART I—THE FOREST |

|

CHAPTER III.

THE LIFE OF A FOREST.

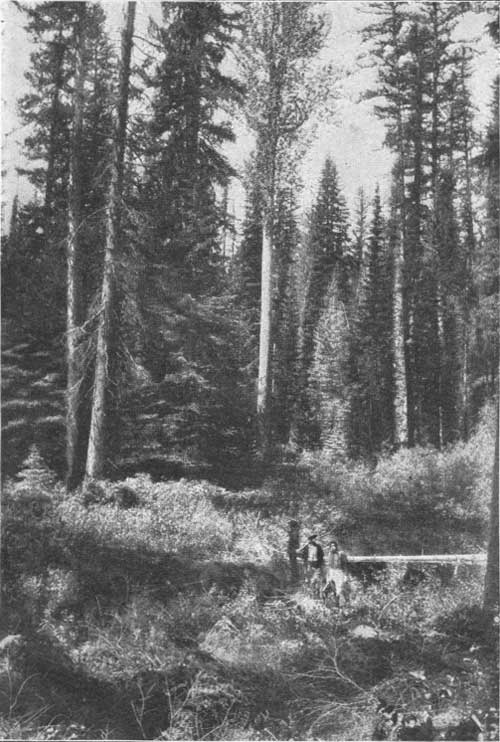

The history of the life of a forest is a story of the help and harm which the trees receive from one another. On one side every tree is engaged in a relentless struggle against its neighbors for light, water, and food, the three things trees need most. On the other side, each tree is constantly working with all its neighbors, even those which stand at some distance, to bring about the best condition of the soil and air for the growth and fighting power of every other tree. (See Pl. XXIII.)

|

| Plate XXIII. A SPRUCE FOREST IN THE ALLEGHENY MOUNTAINS. NORTH CAROLINA. The health and fertility of this forest are due to the mutual help of the trees. |

|

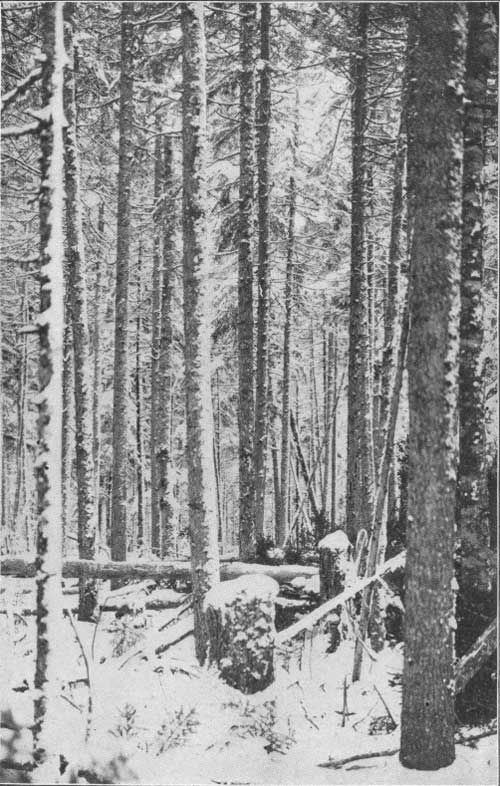

| Fig. 41.—A forest in Switzerland where the mutual help of the trees is at its best. The Sihlwald, where this picture was taken, has been well managed since before the discovery of America. |

A COMMUNITY OF TREES.

The life of a community of trees is an exceedingly interesting one. A forest tree is in many ways as much dependent upon its neighbors for safety and food as are the inhabitants of a town upon one another. (See fig. 41.) The difference is that in a town each citizen has a special calling or occupation in which he works for the service of the commonwealth while in the forest every tree contributes to the general welfare in nearly all the ways in which it is benefited by the community. A forest tree helps to protect its neighbors against the wind, which might overthrow them, and the sun, which is ready to dry up the soil about their roots or to make sun cracks in their bark by shining too hotly upon it. It enriches the earth in which they stand by the fall of its leaves and twigs, and aids in keeping the air about their crowns, and the soil about their roots, cooler in summer and warmer in winter than it would be if each tree stood alone. (See Pl. XXIV.) With the others it forms a common canopy under which the seedlings of all the members of this protective union are sheltered in early youth, and through which the beneficent influence of the forest is preserved and extended far beyond the spread of the trees themselves. But while this fruitful cooperation exists, there is also present, just as in a village or a city, a vigorous strife for the good things of life. For a tree the best of these, and often the hardest to get, are water for the roots and space and light for the crown. In all but very dry places there is water enough for all the trees, and often more than enough, as for example in the Adirondack forest. The struggle for space and light is thus more important than the struggle for water, and as it takes place above ground it is also much more easily observed and studied. (See fig. 42 and Pl. XXV.)

|

| Fig. 42.—On the edge of a very dense forest. The leaning trees are dead, killed by the crowding and shade of their stronger neighbors. Spruce in the White Mountains, New Hampshire. |

Light and space are of such importance because, as we have seen, the leaves can not assimilate or digest food except in the presence of light and air. The rate at which a tree can grow and make new wood is decided chiefly by its ability to assimilate and digest plant food. This power depends upon the number, size, and health of the leaves, and these in turn upon the amount of space and light which the tree can secure.

THE LIFE OF A FOREST CROP.

The story of the life of a forest crop is then largely an account of the competition of the trees for light and room, and, although the very strength which enables them to carry on the fight is a result of their association, still the deadly struggle, in which the victims are many times more in number than those which survive, is apt alone to absorb the attention. Yet the mutual help of the trees to each other is always going quietly on. Every tree continually comforts and assists the other trees, which are its friendly enemies. (See figs. 43, 44.)

|

| Plate XXIV. THE FOREST FLOOR. INTERIOR OF A HARDWOOD FOREST ON ROCKY GROUND. NORTHERN NEW JERSEY. |

|

|

| Fig. 44.—Forest trees standing too far apart to help each other. Lake Chelan, Washington. | |

| |

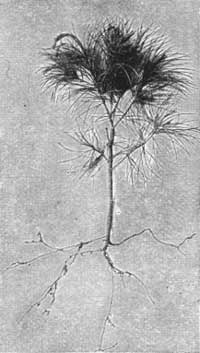

| Fig. 43.—A forest tree, deprived of its companions, slowly dying. A Larch in the Priest River Forest Reserve, Idaho. | Fig. 45.—A White Pine seedling, showing the slender roots. Milford, Pa. |

The purpose of the present chapter is to follow the progress of a forest crop of uniform age from the seed through all the successive phases of its life until it reaches maturity, bears seed in its turn, and finally declines in fertility and strength until at last it passes away and its place is filled by a new generation. The life history which we are about to follow, as it unfolds itself through the course of several hundred years, is full of struggle and danger in youth, restful and dignified in age. The changes which pass over it are vast and full of the deepest interest, but they are very gradual. From beginning to end one stage melts insensibly into the next. Still, in order to study and describe them conveniently, each stage must have limits and a name.

THE SEVEN AGES OF A TREE.

A very practical way of naming and distinguishing trees is the following, which will be used in referring to them hereafter in this discussion. Young trees which have not yet reached a height of 3 feet are seedlings. (See figs. 45-49 and Pls. XXVII, XXVIII.) They are called seedlings in spite of the fact that any tree, of whatever age, if it grew from a seed, is properly called a seedling tree. Trees from 3 to 10 feet in height are small saplings, and from 10 feet in height until they reach a diameter of 4 inches they are large saplings. (See figs. 50, 51, 57.) Small poles are from 4 to 8 inches in diameter, and large poles from 8 to 12 inches in diameter. (See figs. 54, 55, and Pl. XXIX.) Trees from 1 to 2 feet through are standards, and finally, all trees over 2 feet in diameter are veterans. (See figs. 34, 56, and Pls. I, XXXI, XXXII.)

It is very important to remember that all these diameters are measured breast high, or at the height of a man's chest, about 4 feet 6 inches from the ground. In forestry this is, roughly speaking, the general custom.

|

| Plate XXV. WHITE PINES HELPING AND HINDERING EACH OTHER. DUBOIS, PA. |

HOW THE CROP BEGINS.

Let us imagine an abundant crop of tree seeds lying on the ground in the forest. (See Pl. XXVI.) How they came there does not interest us at present; we do not care to know whether they were carried by the wind, as often happens with the winged seeds of many trees, such as Pines and Maples, or whether the squirrels and birds dropped and planted some of them, as they frequently do acorns and chestnuts, or whether the old trees stood closely about and sowed the seed themselves. We will only suppose them to be all of one kind, and to be scattered in a place where the soil, the moisture, and the light are all just us they should be for their successful germination, and afterwards for the later stages of their lives. Even under the best conditions a considerable part of the fallen seed may never germinate, but in this case we will assume that half of it succeeds. (See fig. 46.)

|

| Fig. 46.—Seedlings of Western Hemlock growing thickly on a fallen log. Western Washington. |

As each seed of our forest germinates and pushes its first slender rootlet downward into the earth, it has a very uncertain hold on life. Even for some time afterwards the danger from frost, dryness, and excessive moisture is very serious indeed, and there are many other foes by which the young seedlings may be overcome. It sometimes happens that great numbers of them perish in their earliest youth because their roots can not reach the soil through the thick dry coating of dead leaves which covers it. But our young trees pass through the beginning of these dangers with comparatively little loss, and a plentiful crop of seedlings occupies the ground. As yet, however, each little tree stands free from those about it. As yet, too, the life of the young forest may be threatened or even destroyed by any one of the enemies already mentioned, or it may suffer just as severely if the cover of the older trees above it is too dense. In the beginning of their lives seedlings often require to be protected by the shade of their elders, but if this protection is too long continued they suffer for want of light, and are either killed outright or live only to drag on stunted and unhealthy lives. (See fig. 47.)

|

| Fig. 47.—Seedlings of White Pine under a spreading Scrub Oak. Milford, Pa. The young Pines are overshaded by the worthless Oak, and will die unless the latter is cut away. |

|

| Plate XXVI. CHESTNUT OAK ACORNS GERMINATING IN THE WOODS IN NOVEMBER. MILFORD, PA. The surface of the ground, composed of finely broken fragments of leaves, twigs, etc., under a layer of dead leaves, forms an excellent seed bed when sufficiently moist. Among the leaves are those of the White, Black, and Chestnut Oaks, and the Chestnut. |

THE FOREST COVER ESTABLISHED.

The crop which we are following has had a suitable proportion of shade and light during its earliest years, and the seedlings have spread until their crowns begin to meet. Hitherto each little tree has had all the space in the air and soil that it needed for the expansion of its top and roots. This would have been entirely good, except that meanwhile the soil about the trees has been more or less exposed to the sun and wind, and so has become dryer and less fertile than if it had been under cover, and consequently the growth has been slow. But now that the crowns are meeting, the situation becomes wonderfully changed. The soil begins to improve rapidly, because it is protected by the cover of the meeting crowns and enriched by the leaves and twigs which fall from them. (See figs. 48, 49.)

|

| Fig. 48.—Young White Pines (seedlings) whose lower branches have just begun to interfere. Milford, Pa. These are vigorous young trees, with plenty of light, as maybe seen by the grass which is growing around them. Grass in the woods almost always means that the cover is too thin for the good of the soil. |

THE BEGINNING OF THE STRUGGLE.

In so far the conditions of life are better, and in consequence the growth, and more especially the height growth, begins to show a marked increase. (See fig. 50.) On the other hand, all the new strength is in immediate demand. With the added vigor which the trees are now helping each other to attain comes the most urgent need for rapid development, for the decisive struggle is at hand. The roots of the young trees contend with each other in the soil for moisture and the plant food which it contains, while in the air the crowns struggle for space and light. The latter is by far the more important battle. The victors in it overcome by greater rapidity of growth at the ends of the branches, for it is by growth there, and there only, that trees increase in height and spread of crown. Growth in this way was going on unchecked among the young trees before the crowns met, but now only the upward-growing branches can develop freely. The leaves at the ends of the side branches have now less room and, above all, less light, for they are crowded and thrust aside by those of the other trees. Very often they are bruised by thrashing against their neighbors when the wind blows or even broken off while still in the bud. Leaves exposed to such dangers are unhealthy. They transpire less than the healthy, undisturbed leaves of the upper part of the crown, and more and more of the undigested food from the roots goes to the stronger leaves at the top as the assimilating power of the side leaves dwindles with the loss of light. The young branches share the fortunes of their leaves and are vigorous or sickly according to the condition of the latter. For this reason the growth of the tops increases, while that of the lower lateral branches, as the tops cover them with a deeper and deeper shade, becomes less and less. Gradually it ceases altogether, and the branches perish. This process is called natural pruning, and from the time when it begins the existence of the young forest, unless it should be overtaken by fire or some other great calamity, is practically secure.

|

|

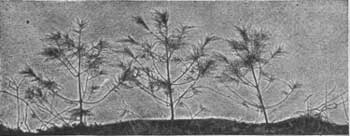

| Fig. 49.—Group of White Pines (small saplings) in an opening among elder trees. Milford, Pa. The lower branches are crowding each other vigorously, and will soon begin to die. | Fig. 50.—Small saplings of White Pine growing thickly together. Milford, Pa. The space between each cluster or whorl of side branches marks one year's growth. These young Pines are beginning to grew rapidly in height because they can no longer spread at the sides. |

|

| Plate XXVII. BALSAM FIR SEEDLINGS UNDER PARTIAL COVER ON LUMBERED LAND. ADIRONDACK MOUNTAINS, NEW YORK. |

GROWTH IN HEIGHT.

At this time, as we have seen, the crowns of all the young trees are growing faster at the tops than at the sides, for there is unlimited room above. (See fig. 51.) But some are growing faster than others, either because their roots are more developed or in better soil than those of the trees about them, because they have been freer from the attacks of insects and other enemies, or for some similar reasons. Some trees have an inborn tendency to grow faster than others of the same species in the same surroundings, just as one son in a family is often taller than the brothers with whom he was brought up.

|

| Plate XXVIII. BALSAM FIR, RED SPRUCE, AND HARDWOOD SEEDLINGS IN AN OPENING IN THE FOREST. ADIRONDACK MOUNTAINS, NEW YORK. The crowns have met, and rapid growth in height has begun. |

Rapid growth in height, from whatever cause it proceeds, brings not only additional light and air to the tree which excels in it, but also the chance to spread laterally, and so to complete the defeat of its slower rivals by overtopping them.

|

|

| Fig. 51.—Large saplings and small poles. Western Larch and Western White Pine. Priest River Forest Reserve, Idaho. | Fig. 54.—Natural pruning on Pine poles still unfinished. Biltmore, N. C. |

|

|

| Fig. 52. | Fig. 53. |

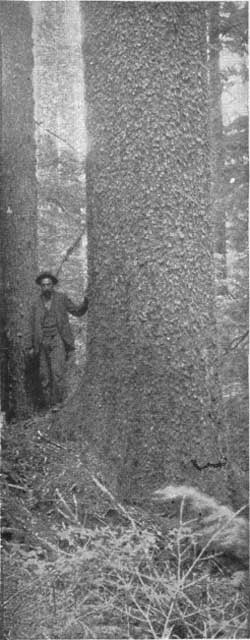

| A tall clear trunk made by natural pruning, and the base of the same tree. Sitka Spruce in the Olympic Forest Reserve, Washington. | |

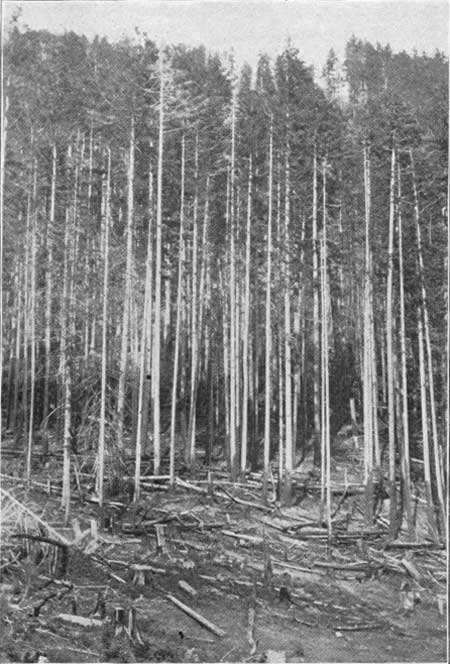

THE STRUGGLE CONTINUED.

Those trees which have gained this advantage over their neighbors are called dominant trees, while the surviving laggards in the race are said to be overtopped when they are hopelessly behind and retarded when less badly beaten. Enormous numbers of seedlings and small saplings are suppressed and killed during the early youth of the forest. In the young crop which we are following many thousands perish upon every acre. Even the dominant trees, which are temporarily free when they rise above their neighbors, speedily come into conflict with each other as they spread, and in the end the greater portion is overcome. It is a very deadly struggle, but year by year the differences between the trees become less marked. Each separate individual clings to life with greater tenacity, the strife is more protracted and severe, and the number of trees which perish grows rapidly smaller. But so great is the pressure when dense groups of young trees are evenly matched in size and rate of growth that it is not very unusual to find the progress of the young forest in its early stages almost stopped, and the trees uniformly sickly and undersized, on account of the crowding.

|

| Plate XXIX. A FOREST OF SPRUCE POLES. ADIRONDACK MOUNTAINS NEW YORK. |

|

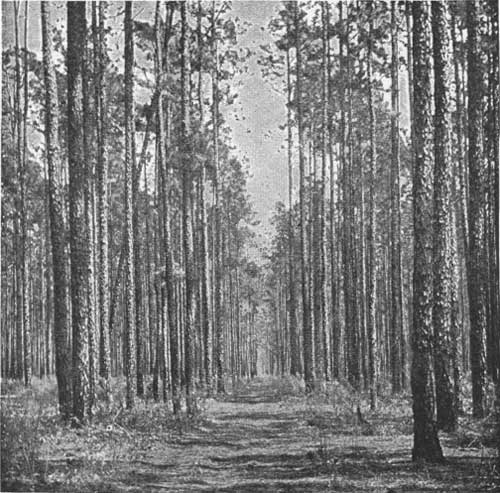

| Fig. 55.—Poles of Longleaf Pine. Southern Florida. |

|

| Fig. 56.—Standards and poles of Spruce. White Mountains, New Hampshire. |

The forest we have been following has now passed through the small-sapling stage, and is composed chiefly, but not exclusively, of large saplings. Among the overtopped and retarded trees, which often remain in size classes which the dominant trees have long since outgrown, there are still many low saplings. Even between the dominant trees, in a healthy forest, there are always great differences. Increase in height is now going on rapidly among these high saplings, and either in this stage or the next a point is reached when the topmost branches make their longest yearly growth, which is one way of saying that the trees make their most rapid height growth as large saplings or small poles. (See P1. XXIX.) Later on, as we shall see, these upper branches lengthen much more slowly, until, in standards and veterans, the growth in height gradually diminishes, and in very old trees finally ceases altogether.

|

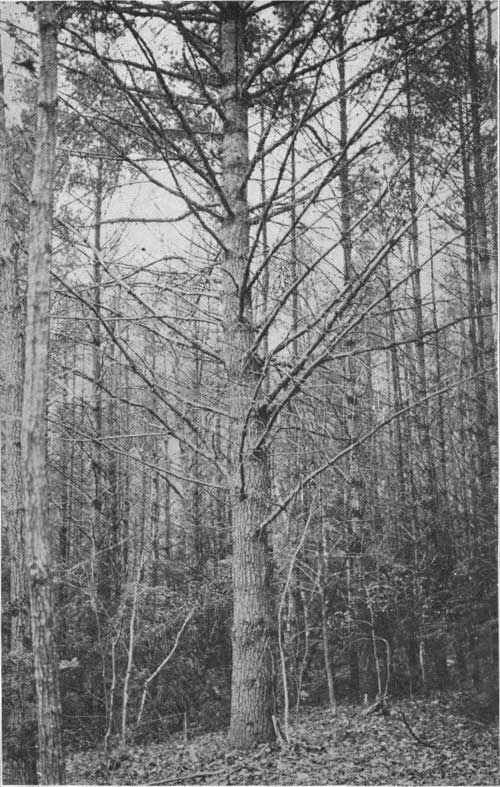

| Plate XXX. IMPERFECT NATURAL PRUNING ON A WHITE PINE THAT STOOD TOO MUCH ALONE IN EARLY YOUTH. MILFORD, PA. |

NATURAL PRUNING.

|

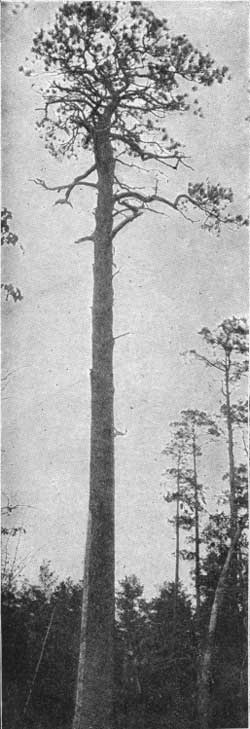

| Fig. 57.—Pointed crowns of saplings of Longleaf Pine growing rapidly in height. Southern Florida. |

While the trees are pushing up most rapidly the side branches are most quickly overshaded, and the process of natural pruning goes on with the greatest vigor. Natural pruning is the reason why old trees in a dense forest have only a small crown high in the air, and why their tall, straight trunks are clear of branches to such a height above the ground. (See figs. 52-56 and Pl. XXX.) The trunks of trees grown in the open, where even the lower limbs have abundance of light, are branched either quite to the ground or to within a short distance of it. But in the forest not only are the lower side branches continually dying for want of light, but the tree rids itself of them after they are dead and so frees its trunk from them entirely. When a branch dies the annual layer of new wood is no longer deposited upon it. Consequently the dead branch, where it is inserted in the tree, makes a little hole in the first coat of living tissue formed over the live wood after its death. The edges of this hole make a sort of collar about the base of the dead branch, and as a new layer is added each year they press it more and more tightly. So strong does this compression of the living wood become that at last what remains of the dead tissue has so little strength that the branch is broken off by an ice storm or by the wind, or even falls of its own weight. Then in a short time, if all goes well, the hole closes, and after a while little or no exterior trace of it remains. Knots, such as those which are found in boards, are the marks left in the trunk by branches which have disappeared.

|

| Fig. 58.—An old Longleaf Pine with flattened crown. Eastern North Carolina. |

THE CULMINATION OF GROWTH.

While the young trees are making clean trunks so rapidly during the period of greatest yearly height growth they are also making their greatest annual gains in diameter, for these two forms of growth generally culminate about the same time. A little later, if there is any difference, the young forest's highest yearly rate of growth in volume is also reached. For a time these three kinds of growth keep on at the same rate as in the past, but afterwards all three begin to decrease. Growth in diameter, and in volume also, if the trees are sound, goes on until extreme old age, but height growth sinks very low while the two others are still strong. For many years before this happens the struggle between the trees has not been so deadly, because they have been almost without the means of overtopping one another. When the end of the period of principal height growth is reached the trees are interfering with each other very little, and the struggle for life begins again in a different way. As the principal height growth ceases, and the tops no longer shoot up rapidly above the side branches, the crowns lose their pointed shape and become comparatively flat. (See figs. 57, 58.) The chief reason why trees stop growing in height is that they are not able to keep the upper parts of their crowns properly supplied with water above a certain distance from the ground. This distance varies in different kinds of trees, and with the health and vigor of the tree in each species, but there is a limit in every case above which the water does not reach. The power of the pumping machinery, more than any other quality, determines the height of the tree.

|

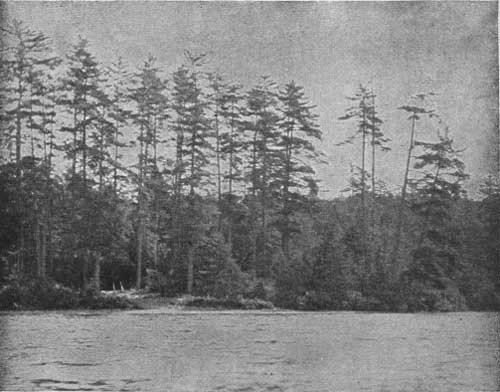

| Plate XXXI. A DENSE FOREST OF STANDARDS AND VETERANS OF RED FIR AND LOWLAND FIR. LAKE CRESCENT, OLYMPIC PENINSULA, WASHINGTON. |

THE END OF THE STRUGGLE.

|

| Fig. 59.—Diagram to show why a sharply conical crown receives more light than a flat one. |

Now that the tree can no longer expand at the top, it must either suffer a great loss in the number of its leaves or be able to spread at the sides; for it is clear that not nearly so many leaves can be exposed to the light in the flattened crown as in the pointed one, just as a pointed roof has more surface than a flat one. (See fig. 59.) It is just at this time, too, that the trees begin to bear seed most abundantly, and it is of the greatest importance to each tree that its digestive apparatus in the leaves should be able to furnish a large supply of digested food. Consequently the struggle for space is fiercely renewed, only now the trees no longer attempt to overtop one another, having lost the power, but to crowd one another away at the sides. (See fig. 60.) The whole forest might suffer severely at this point from a deadlock such as sometimes happens in early youth were it not for the fact that the trees, as they grow older, become more and more sensitive to any shade. Many species which stand crowding fairly well in youth can not thrive in age unless their crowns are completely free on every side. Each of the victors in this last phase of the struggle is the survivor of hundreds (or sometimes even of thousands) of seedlings. Among very numerous competitors they have shown themselves to be the best adapted to their surroundings. (See fig. 61 and Pl. XXXI.)

|

| Fig. 60—White Pine standards in the Adirondack Mountains, New York. |

|

| Plate XXXII. YOUNG GROWTH UNDER OLD TREES. SOUTHWESTERN OREGON. |

Natural selection has made it clear that these are the best trees for the place. These are also the trees which bear the seed whence the younger generations spring. Their offspring will inherit their fitness to a greater or less degree, and in their turn will be subjected to the same rigorous test, by which only the best are allowed to reach maturity. Under this sifting out of the weak and the unfit, our native trees have been prepared, through thousands of generations, to meet the conditions under which they must live. This is why they are so much more apt to succeed than species from abroad, which have not been fitted for our climate and soil by natural selection.

|

| Fig. 61.—An open forest of intolerant Longleaf Pine. Southern Florida. |

|

| Plate XXXIII. FOREST ON THE SOUTH FORK OF THE FLATHEAD RIVER, MONTANA. All the stages of tree growth are often present in one place, as here. |

The forest which we saw first in the seed has now passed through all the more vigorous and active stages of its life. The trees have become standards and veterans, and large enough to be valuable for lumber. Rapid growth in height has long been at an end, diameter growth is slow, and the forest as a whole is increasing very little in volume as time goes on. The trees are ripe for the harvest.

Out of the many things which might happen to our mature forest we will only consider three.

DEATH FROM WEAKNESS AND DECAY.

In the first place, we will suppose that it stands untouched until, like the trees of the virgin forest, it meets its death from weakness and decay.

|

| Fig. 62.—Lumbered and burned forest near Port Crescent, Olympic Peninsula, Washington. |

The trees of the mature primeval forest live on, if no accidents intervene, almost at peace among themselves. At length all conflict between them ends. The whole power of each tree is strained in a new struggle against death, until at last it fails. One by one the old trees disappear. But long before they go, the forerunners of a new generation have sprung up wherever light came in between their isolated crowns. As the old trees fall, with intervals, often of many years, between their deaths, young growth of various ages rises to take their place, and when the last of the old forest has vanished there may be differences of a hundred years among the young trees which succeed it. (See Pl. XXXII.) An even-aged crop of considerable extent, such as we have been considering, is not usual in the virgin forest, where trees of very different ages grow side by side, and when it does occur, the next generation is far less uniform. The forest whose history has just been sketched was chosen, not because it represents the most common type of natural forest, but because it illustrates better than any other the life and progress of forest growth. (See Pl. XXXIII.)

The wood of a tree which dies in the forest is almost wholly wasted. For a time the rotting trunk may serve to retain moisture, but there is little use for the carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen which make up its greater part. The mineral constituents alone form a useful fertilizer, but most often there is already an abundance of similar material in the soil. Not only is the old tree lost, but ever since its maturity it has done little more than intercept, to no good purpose, the light which would otherwise have given vitality to a valuable crop of younger trees. It is only when the ripe wood is harvested properly and in time that the forest attains its highest usefulness.

DESTRUCTIVE LUMBERING.

A second thing which may happen to a forest is to be cut down without care for the future. The yield of a forest lumbered in the usual way is more or less thoroughly harvested, it is true, but at an enormous cost to the forest. Ordinary lumbering injures or destroys the young growth, both in the present and for the future, provokes and feeds fires, and does harm of many other kinds. In many cases its result is to annihilate the productive capacity of forest land for tens or scores of years to come. (See fig. 62 and Pl. XXXIV.)

|

| Plate XXXIV. DESTRUCTIVE LUMBERING IN THE COAST REDWOOD BELT. CALIFORNIA. Logging works in Bear Gulch, Eureka, Humboldt County. |

CONSERVATIVE LUMBERING.

The methods of forestry, on the other hand, maintain and increase both the productiveness and the capital value of forest land; harvest the yield far more completely than ordinary lumbering, although less rapidly; prepare for, encourage, and preserve the young growth; tend to keep out fires; and in general draw from the forest, while protecting it, the best return which it is capable of giving.

The application of these methods is the third possibility for the crop just described. There are still many places in the United States where transportation is so costly that, as yet, forestry will not pay from a business point of view. Elsewhere right forest management is the wisest, safest, and most satisfactory way of dealing with the forest. It is briefly described in Part II of this primer.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

primer/chap3-1.htm Last Updated: 06-Jul-2009 |