|

A PRIMER OF FORESTRY PART I—THE FOREST |

|

CHAPTER IV.

ENEMIES OF THE FOREST.

The forest is threatened by many enemies, of which fire and reckless lumbering are the worst. In the United States sheep grazing and wind come next. Cattle and horses do much less damage than sheep, and snow break is less costly than windfall. Landslides, floods, insects, and fungi are sometimes very harmful. In certain situations numbers of trees are killed by lightning, which has also been known to set the woods on fire, and the forest is attacked in many other ways. For example, birds and squirrels often prevent young growth by devouring great quantities of nuts and other seeds, while porcupines and mice frequently kill young trees by gnawing away their bark.

MAN AND NATURE IN THE FOREST.

Most of these foes may be called natural enemies, for they would injure the forest to a greater or less extent if the action of man were altogether removed. Wild animals would take the place of domestic sheep and cattle to some degree, and fire, wind, and insects would still attack the forest. But many of the most serious dangers to the forest are of human origin. Such are destructive lumbering, and excessive taxation on forest lands, to which much bad lumbering is directly due. So high are these taxes, for in many cases they amount to 5 or even 6 per cent yearly on the market value of the forests, that the owners can not afford to pay them and hold their lands. Consequently they are forced to cut or sell their timber in haste and without regard to the future. When the timber is gone the owners refuse to pay taxes any longer, and the devastated lands revert to the State. Many thousand square miles of forest have been ruined by reckless lumbering because heavy taxes forced the owners to realize quickly and once for all upon their forest land, instead of cutting it in a way to insure valuable future crops. For the same reason many counties are now poor that might, with reasonable taxation of timber land, have been flourishing and rich.

|

| Fig. 63.—A burnt forest in the Priest River Forest Reserve, Idaho. |

|

| Plate XXXV. A BURNT FOREST IN THE HIGH MOUNTAINS. CASCADE FOREST RESERVE, OREGON. The branches and smaller trees were bent and twisted by the intense heat. |

A short description of destructive lumbering will be found in Part II of this primer, together with some consideration of the most effective remedy, which is found in conservative ways of handling the forest, that is, in forest management.

GRAZING IN THE FOREST.

Whether grazing animals are comparatively harmless to the forest or among its most dangerous enemies depends on the age and character of the woods as well as upon the kind of animals that graze. A young forest is always more exposed to such injury than an old one, and steep slopes are more subject to damage than more level ground. Whether the young trees are conifers, and so more likely to suffer from trampling than from being eaten, or broadleaf trees, and so more likely to be devoured, they should be protected from pasturing animals until they are large enough to be out of danger.

|

|

Fig. 64.—A band of sheep passing through the forest. These sheep were being herded illegally in a forest reserve. Eastern slope of the Cascade Mountains near Badger Lake, Wasco County, Oregon. |

|

| Fig. 65.—A forest of Lodgepole Pine in a region used for grazing. Bighorn Forest Reserve, Wyoming. |

|

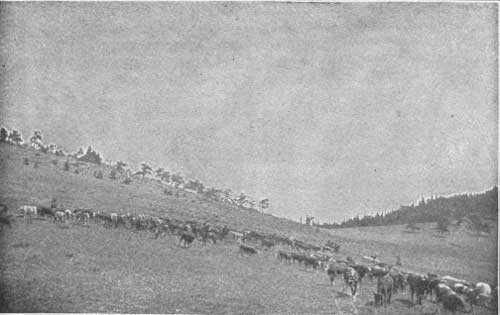

| Plate XXXVI. A BAND OF SHEEP ON A HIGH PRAIRIE. EASTERN SLOPE OF THE CASCADE MOUNTAINS, WASCO COUNTY, OREGON. ALTITUDE, 5,800 FEET. These sheep were being herded illegally in a forest reserve. |

GRAZING AND FIRE.

Grazing in the forest does harm in three ways. First, it is a fertile cause of forest fires. (See figs. 64-66 and Pl. XXXV.) Burning the soil cover of grass and other plants improves the grazing, either permanently, by destroying the forest and so extending the area of pasturage, or temporarily, by improving the quality of the feed. For one or the other of these objects, but chiefly for the latter, vast areas are annually burned over in nearly every part of the United States where trees grow. The great majority of these fires do not kill the old trees, but the harm they do the forest and, eventually, the fodder plants themselves, is very serious indeed. The sheep men of the West are commonly accused of setting many forest fires to improve the grazing, and they are also vigorously defended from this charge. But the fact remains that large areas where sheep now graze would be covered with forests except for the action of more or less recent fires.

|

| Fig. 66.—Cattle in the Bighorn Forest Reserve, Wyoming. |

TRAMPLING.

Trampling is the second way in which grazing animals injure the forest. Cattle and horses do comparatively little harm, although their hoofs compact the soil and often tear loose the slender rootlets of small trees. Sheep, on the contrary, are exceedingly harmful, especially on steep slopes and where the soil is loose. In such places their small, sharp hoofs cut and powder the soil, break and overthrow the young trees, and often destroy promising young forests altogether. (See Pls. XXXVI, XXXVII, XXXVIII.) In many places the effect of the trampling is to destroy the forest floor and to interfere very seriously with the flow of streams. In the Alps of southern France sheep grazing led to the destruction, first, of the mountain forests, and then of the grass which had replaced them, and thus left the soil fully exposed to the rain. Great floods followed, beds of barren stones were spread over the fertile fields by the force of the water, and many rich valleys were almost or altogether depopulated. Besides the loss occasioned in this way, it has cost the French people tens of millions of dollars to repair the damage begun by the sheep, and the task is not yet finished. The loss to the nation is enormously greater than any gain from the mountain pastures could have been, and even the sheep owners themselves, for whose profit the damage was done, were losers in the end, for their industry in that region was utterly destroyed.

|

| Plate XXXVII. A BURNT FOREST IN WHICH THE YOUNG TREES ARE RETURNING AMONG LOGS AND BRUSH WHERE SHEEP CAN NOT PASS. EASTERN SLOPE OF THE CASCADE MOUNTAINS, WASCO COUNTY, OREGON. Between the logs in the foreground all young growth has been trampled out by sheep. |

BROWSING.

The third way in which grazing animals injure the forest is by feeding on the young trees. In the western part of the United States, where most of the forests are evergreen, this is far less important than the damage from either fire or trampling, for sheep and other animals seldom eat young conifers if they can get other food. Even where broadleaf trees prevail browsing rarely leads to the destruction of any forest, although it commonly results in scanty young growth, often maimed and unsound as well. Goats are especially harmful, and where they abound the healthy reproduction of broadleaf trees is practically impossible. In the United States they are fortunately not common. Cattle devour tender young shoots and branches in vast quantities, often living for months on little else, and sheep are destructive in the same way. Hogs also find a living in the forest, but they are less harmful, because a large part of their food consists of seeds and nuts. East of the Great Plains very large numbers of cattle and hogs are turned into the woods, but sheep grazing in the forest is most widely developed in the West, and especially in California, where it should be prevented altogether, in Oregon and Washington, where it should be regulated and restricted, and in some interior regions, like Wyoming and New Mexico, where it should be rigidly excluded from all steep mountain regions, and carefully regulated on more level ground.

|

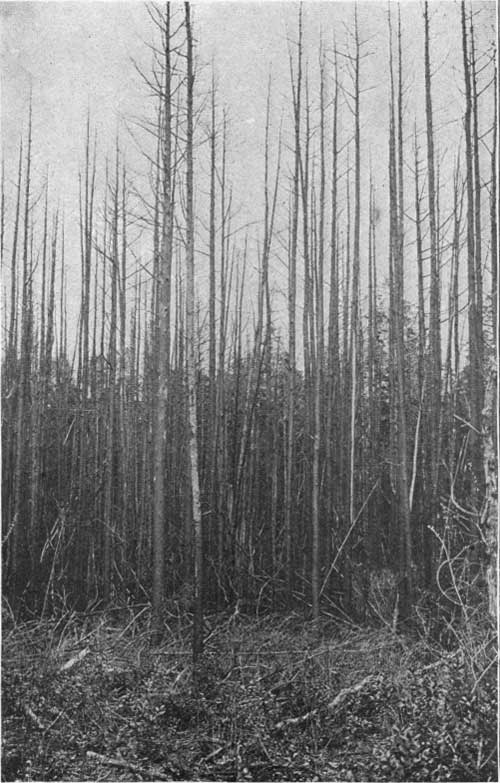

| Fig. 67.—Larch trees killed by the larva of a small sawfly. The land has just been lumbered for Spruce. Adirondack Mountains, New York. |

FOREST INSECTS.

|

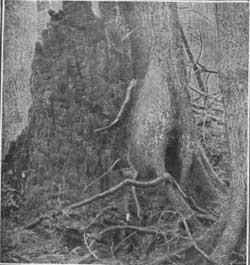

| Fig. 68.—Rotting wood from an old Red Fir stub. The young Hemlock to the right began life on the bark of the Fir. Olympic Forest Reserve, Washington. |

Insects are constantly injuring the forest, just as year by year they bring loss to the farm. Occasionally their ravages attain enormous proportions. Thus a worm, which afterwards develops into a sawfly, has since 1882 killed nearly every full-grown Larch in the Adirondacks by eating away the leaves. (See fig. 67.) Even the small and vigorous Larches do not escape altogether from these attacks. Conifers, such as the Larch and Spruce, are much more likely to suffer from the attacks of insects than broadleaf trees. About the year 1876 small bark beetles began to kill the mature Spruce trees in the Adirondacks, and ten years later, when the worst of the attack was past, the forest was practically deprived of all its largest Spruces. This pest is still at work in northern New Hampshire and in Maine.

FOREST FUNGI.

Fungi attack the forest in many ways. Some kill the roots of trees, some grow upward from the ground into the trees and change the sound wood of the trunks to a useless rotten mass, and the minute spores (or seeds) of others float through the air and come in contact with every external part of the tree above ground. (See fig. 68.) Wherever the wood is exposed there is danger that spores will find lodgment and breed disease. This is a strong reason why all wounds, such as those made in pruning, should be covered with some substance like paint or tar to exclude the air and the spores it carries.

|

| Plate XXXVIII. SLOPE OVER WHICH A BAND OF SHEEP HAS PASSED. EASTERN SLOPE OF THE CASCADE MOUNTAINS, WASCO COUNTY, OREGON. The area was burnt at one time. Since the burning the humus has been kept from forming and the young trees from springing up by the sheep which pass over the tract every year. |

|

|

| Fig. 69.—A windfall in the Olympic Forest Reserve, Washington. | Fig. 70.—In the same windfall. Olympic Forest Reserve, Washington. |

WIND IN THE FOREST.

|

| Fig. 71.—A young Spruce loaded with snow. Avalanche Lake, Adirondack Mountains, New York. |

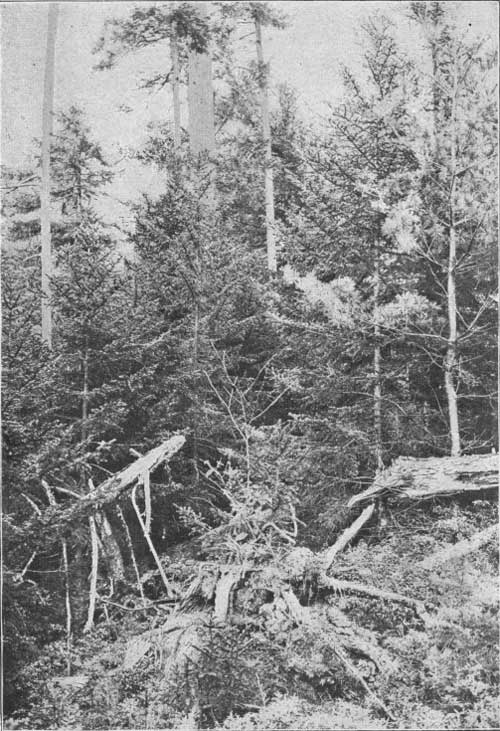

The effect of wind in the virgin forest is not wholly injurious. Although in many regions it overthrows great numbers of old trees, their removal is usually followed by a vigorous young growth where the old trees stood. (See Pl. XXXIX.) In this way the wind helps to keep the forest full of young and healthy trees. But it also breaks and blows down great numbers of useful growing members of the forest. Much of this windfall occurs among shallow-rooted trees, or where the ground is soft because soaked with water, or where the trees have been weakened by unsoundness or fire. Some storms are strong enough to break the trees they can not overthrow. Damage from wind is not uncommon in many parts of the United States, and in places the loss from it is very serious. (See figs. 69, 70.) Near the town of High Springs, for example, in Alachua County, Fla., in a region very subject to such accidents, there is a tract of many square miles, once covered with Longleaf Pine, over which practically all the trees were killed by a great storm several years ago. Some were thrown flat, some were so racked and so broken in the top that they died, and very many were snapped off at from 15 to 30 feet above the ground. There is little use in taking precautions against such great calamities, yet the loss from windfall may be very much reduced by judicious cutting. An unbroken forest is least exposed.

|

| Plate XXXIX. YOUNG SPRUCES AND PINES SPRINGING UP IN A WINDFALL. ADIRONDACK MOUNTAINS, NEW YORK. |

SNOW IN THE FOREST.

Snow often loads down, breaks, and crushes tall young trees, especially if wet snow falls heavily before the broadleaf trees have shed their foliage in the fall. Such injury is difficult to guard against, but it is well to know that very slim, tall trees suffer more than those whose growth in diameter and height have kept better pace with each other. (See figs. 71, 72, and Pl. XL.) In many regions snow is so useful in protecting the soil and the young trees that the harm it does is quite overbalanced by its benefits.

FOREST FIRES.

|

| Fig. 72.—A young Red Fir bent down by snow in early youth. It is scarred by fire on the underside. Washington Forest Reserve. |

Of all the foes which attack the woodlands of North America no other is so terrible as fire. Forest fires spring from many different causes. They are often kindled along railroads by sparks from the locomotives. Carelessness is responsible for many fires. Settlers and farmers clearing land or burning grass and brush often allow the fire to escape into the woods. (See fig. 73.) Some one may drop a half-burned match or the glowing tobacco of a pipe or cigar, or a hunter or prospector may neglect to extinguish his camp fire, or may build it where it will burrow into the thick duff far beyond his reach, to smolder for days, or weeks, and perhaps to break out as a destructive fire long after he is gone. Many fires are set for malice or revenge, and the forest is often burned over by huckleberry pickers to increase the next season's growth of berries, or by the owners of cattle or sheep to make better pasture for their herds.

|

| Fig. 73.—A clearing an Spruce timber. The great cost and difficulty of such clearing is well illustrated. In the foreground is a field of potatoes. Olympic Forest Reserve, Washington. |

There is danger from forest fires in the dry portions of the spring and summer, but those which do most harm usually occur in the fall. At whatever time of the year they appear, their destructive power depends very much on the wind. They can not travel against it except when burning up hill, and not even then if the wind is strong. The wind may give them strength and speed by driving them swiftly through unburned, inflammable forests, or it may extinguish the fiercest fire in a short time by turning it back over its path, where there is nothing left to burn. In fighting forest fires the wind is always the first thing to consider, and its direction must be carefully watched. A sudden change of wind may check a fire, or may turn it off in a new direction and perhaps threaten the lives of the men at work by driving it suddenly down upon them.

|

| Plate XL. DAMAGE FROM SNOW IN THE SIHLWALD, ZURICH, SWITZERLAND. The slim trees were bent and the stouter trees unharmed by heavy snow, which fell in autumn, before the leaves had dropped. |

HISTORIC FOREST FIRES.

When all the conditions are favorable, forest fires sometimes reach gigantic proportions. A few such fires have attained historic importance. One of these is the Miramichi fire of 1825. It began its greatest destruction about 1 o'clock in the afternoon of October 7 of that year, at a place about 60 miles above the town of Newcastle, on the Miramichi River, in New Brunswick. Before 10 o'clock at night it was 20 miles below Newcastle. In nine hours it had destroyed a belt of forest 80 miles long and 25 miles wide. Over more than two and a half million acres almost every living thing was killed. Even the fish were afterwards found dead in heaps on the river banks. Five hundred and ninety buildings were burned, and a number of towns, including Newcastle, Chatham, and Douglastown, were destroyed. One hundred and sixty persons perished, and nearly a thousand head of stock. The loss from the Miramichi fire is estimated at $300,000, not including the value of the timber.

|

| Fig. 74.—A forest fire on the Yukon River, Alaska. Bow of a canoe to the left. |

|

| Fig. 75.—Fire sometimes renews an old forest by killing the veterans and so permitting vigorous young trees to take their place. The rotting stubs of fire-killed veterans of Red Fir are seen in the picture surrounded by young standards of Red Fir and Western Hemlock. Olympic Forest Reserve, Washington. |

|

| Plate XLI. BURNT-OVER MOUNTAINS ABOVE THE FLATHEAD VALLEY. MONTANA. The white patches on the mountain in the background are made partly by snow and partly by bleached fire-killed trees still standing. The trees in the foreground are Western Yellow Pine and Red Fir. |

In the majority of such forest fires as this the destruction of the timber is a more serious loss, by far, than that of the cattle and buildings, for it carries with it the impoverishment of a whole region for tens or even hundreds of years afterwards. The loss of the stumpage value of the timber at the time of the fire is but a small part of the damage to the neighborhood. The wages that would have been earned in lumbering, added to the value of the produce that would have been purchased to supply the lumber camps, and the taxes that would have been devoted to roads and other public improvements, furnish a much truer measure of how much, sooner or later, it costs a region when its forests are destroyed by fire. (See figs. 76-81, and Pls. XLI, XLVI, XLVII.)

|

| Fig. 76.—A Rocky Mountain coniferous forest killed by fire. Valley of the North Fork of Sun River, Montana. |

|

| Fig.77.—A burnt forest near Monte Cristo in the Washington Forest Reserve. |

The Peshtigo fire of October, 1871, was still more severe than the Miramichi. It covered an area of over 2,000 square miles in Wisconsin, and involved a loss, in timber and other property, of many millions of dollars. Between 1,200 and 1,500 persons perished, including nearly half the population of Peshtigo, at that time a town of 2,000 inhabitants. Other fires of about the same time were most destructive in Michigan. A strip about 40 miles wide and 180 miles long, extending across the central part of the State from Lake Michigan to Lake Huron, was devastated. The estimated loss in timber was about 4,000,000,000 feet board measure and in money over $10,000,000. Several hundred persons perished.

|

| Fig. 78.—A single Red Fir, spared by the fire, remains to indicate what the burnt area is capable of producing. Washington Forest Reserve. |

In the early part of September, 1881, great fires covered more than 1,800 square miles in various parts of Michigan. The estimated loss, in property, in addition to many hundred thousand acres of valuable timber, was more than $2,300,000. Over 5,000 persons were made destitute and the number of lives lost is variously estimated at from 150 to 500.

The most destructive fire of more recent years was that which started near Hinckley, Minn., September 1, 1894. While the area burned over was less than in some other great fires, the loss of life and property was very heavy. Hinckley and six other towns were destroyed, about 500 lives were lost, more than 2,000 persons were left destitute, and the estimated loss in property of various kinds was $25,000,000. Except for the heroic conduct of locomotive engineers and other railroad men the loss of life would have been far greater. This fire was all the more deplorable, because it was wholly unnecessary. For many days before the high wind came and drove it into uncontrollable fury, it was burning slowly close to the town of Hinckley, and could have been put out.

|

| Plate XLII. A FIRE-SCAR AT THE FOOT OF A FALLEN SEQUOIA. SIERRA NEVADA, CALIFORNIA. The attempt of the tree to cover the wound is plainly seen on the cut at the right. |

|

| Plate XLIII. FIRE BURNING ALONG A FALLEN LOG. CASCADE RANGE, OREGON. |

MEANS OF DEFENSE.

The means of fighting forest fires are not everywhere the same, for they burn in many different ways; but in every case the best time to fight a fire is at the beginning, before it has had time to spread. A delay of even a very few minutes may permit a fire that at first could easily have been extinguished to gather headway and get altogether beyond control.

|

| Fig. 79.—A surface fire burning slowly against the wind. Southern New Jersey. |

When there is but a thin covering of leaves and other waste on the ground a fire usually can not burn very hotly or move with much speed. The fires in most hardwood forests are of this kind. They seldom kill large trees, but they destroy seedlings and saplings and kill the bark of older trees in places near the ground. The hollows at the foot of old Chestnuts and other large trees are often the results of these fires, which occur again and again, and so enlarge the wounds instead of allowing them to heal. (See Pl. XLII.) Moderate fires also occur in dense coniferous forests when only the top of a thick layer of duff is dry enough to burn. The heat may not be great enough to kill any but the smallest and tenderest young trees, but that does not mean that such fires do no harm. The future of the forest depends on just such young growth, and whenever the forest floor, which is so necessary both to the trees and for the water supply, is injured or destroyed by fire, the forest suffers harm.

SURFACE FIRES.

Surface fires may be checked if they are feeble by beating them out with green branches, or by raking the leaves away from a narrow strip across their course. The best tool for this purpose is a four-tined pitchfork, or a common stable fork. In sandy regions a thin and narrow belt of sand is easily and quickly sprinkled over the ground with a shovel, and will check the spread of a weak fire, or even of a comparatively hot one if there is no wind. Dirt or sand thrown on a burning fire is one of the best of all means for putting it out. (See fig. 79.)

|

| Plate XLIV. A BURNT PINE FOREST. SOUTHERN NEW JERSEY. The fire, which burnt the leaves from nearly all the crowns, had passed less than twenty-four hours before the picture was taken. |

|

| Plate XLV. ROAD AND PATH ACTING AS FIRE LINES. NEW JERSEY. This picture shows how a road or a fire path may check a surface fire. The limit of fire is shown by the unburned grass. Even the small path in the foreground was sufficient to check this fire. |

|

| Fig. 80.—The effect of repeated fires. Not only the old trees are dead, but the seedlings which succeeded them have perished also. Western Yellow Pine in the Black Hills Forest Reserve, South Dakota. |

In dense forests with a heavy forest floor, fires are often hot enough not only to kill the standing timber, but to consume the trunks and branches altogether, and even to follow the roots far down into the ground. In forests of this kind fire spreads easily, creeping along on the surface or through the duff or under the bark of rotting fallen trees. (See Pl. XLIII.) In the same way it climbs dead standing trees, and breaks out in bursts of flame high in the air. Dead trees help powerfully to spread a fire, for in high winds loose pieces of their burning bark are carried to almost incredible distances, and drop in to the dry forest far ahead, while in calm weather they scatter burning fragments all about them when they fall. (See fig. 80.)

GROUND FIRES.

When the duff is very deep or the soil peaty, a fire may burn beneath the surface of the ground for weeks or even months sometimes showing its presence by a little smoke, sometimes without giving any sign of life. Even a heavy rain may fail to quench afire of this kind, which often breaks out again long after it is believed to be entirely extinct. Fires which thus burn into the ground can sometimes be checked only by digging a trench through the layer of decaying wood and other vegetable matter to the mineral soil beneath. Ground fires usually burn much more slowly than surface fires, but they are exceptionally long lived, and very hard to put out, it is of the first importance to attack such fires quickly, before they have had time to burrow far beneath the surface of the ground. Surface fires are usually far less troublesome but in either case fires which kill the trees are generally repeated again and again until the dead timber is consumed. (See fig. 81 and Pls. XLIV, XLV, XLVI, XLVII.)

|

| Plate XLVI. FALLEN AND STANDING FIRE-KILLED TIMBER READY FOR THE NEXT FIRE. PRIEST RIVER FOREST RESERVE, IDAHO. |

|

| Fig. 81.—The result of recurring fires. The forest floor has disappeared and the pure white sand, which looks like snow in the picture, is left without protection. Southern New Jersey. |

BACK-FIRING.

|

| Fig. 82.—Setting a back-fire on the windward side of a read. Southern New Jersey. Drawn from a photograph. |

The most dangerous and destructive forest fires are those which run both along the ground and in the tops of the trees. When a fire becomes intensely hot on the ground it may run up the bark, especially if the trees are conifers, and burn in the crowns. Such fires are the fiercest and most destructive of all. Traveling sometimes faster than a man can run, they consume enormous quantities of valuable timber, burn fences, buildings, and endanger domestic animals and or even destroy human lives. They can be checked only by rain or change of wind, or by meeting some barrier which they can not pass. A barrier of this kind is often made by starting another fire some distance ahead of the principal one. This back-fire, as it is called, must be allowed to burn only against the wind and toward the main fire, so that when the two fires meet both must go out for lack of fuel. To prevent it from moving with the wind, a back-fire should always be started on the windward side of a road or a raked or sanded strip, or some other line which it can be kept from crossing. (See fig. 82.) If it is allowed to escape it may become as dangerous as the main fire itself. Back-fires are sometimes driven beyond control by a change of wind, but the chief danger from their use is caused by persons who, in excitement or fright, light them at the wrong time or in the wrong place. Still there is no other means of fighting fires so powerful, and none so effective when rightly used.

|

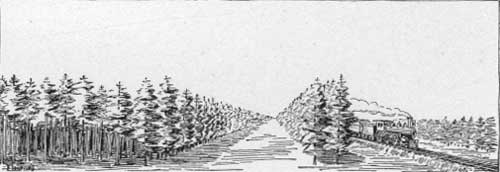

| Fig. 83.—A fire line along a railroad with two cleared spaces separated by a double row of trees intended to catch the sparks. |

|

| Plate XLVII. A CEDAR SWAMP AFTER A FIRE. SOUTHERN NEW JERSEY. |

FIRE LINES.

Fire lines—strips kept free from all inflammable material by burning or otherwise—are very useful in checking small fires and of great value as lines of defense in fighting large ones. (See fig. 83.) They are also very effective in keeping fires out of the woods, as, for example, along railroad tracks. But without men to do the fighting they are of as little use against really dangerous fires as forts without soldiers against invading armies.

END OF PART I.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Part II >>> |

|

primer/chap4-1.htm Last Updated: 06-Jul-2009 |