|

The Clearwater Story: A History of the Clearwater National Forest |

|

Chapter 12

Working & Living Conditions

During the history of the Forest Service nothing has changed more than work hours, pay and working conditions. Of course, this isn't true of just the Forest Service. It is true, perhaps to a lesser degree, in almost every industry. When the forests were created, men worked six days a week from sun up until sundown. Pay for Rangers was $50 a month and they were laid off during the winter months without pay. A Ranger could not exist unless he had other work during the off season. Trappers fit into the work well, but others worked at anything they could find. The prospectors liked the job since they could do a lot of looking around and get pay while doing it. In addition to the low pay, Rangers were required to furnish their own stock, personal equipment and food. They even had to furnish their own snowshoes. The Forest Service did winter the Ranger's stock which gave rise to the comment that the Forest Service took better care of the horses than they did of their men. The requirement that a Ranger furnish his own stock was discontinued in 1924.

So far as houses were concerned there were none. Tents were used except at No. 1 and the Musselshell where small cabins were built. The other stations had tents, but the Rangers did not live there in the winter. Marriage for Rangers was frowned on, but if they were married, they usually left their wives in town. In 1908 and 1909 a special Act of Congress authorized the Forest Service to use the National Forest receipts to build improvements. The Forest Service came up with a standard cabin. It was made of hewed logs with two rooms downstairs and an attic type upstairs which also served as either one or two rooms. There was no basement. There was an outdoor toilet. The cabin was usually built near a spring or creek for household water. There are a few of these old buildings still in existence in the Region, but none on the Clearwater. Into this two-room house a Ranger had to crowd his family, if married, and his office. His wife answered the telephone and often cooked for visiting officers and firefighters without pay. Then the Forest Service had the audacity to charge him rent. Conditions were far from satisfactory. Many men quit as soon as they could find steady work or improve the lot of their families.

During World War I, there was a mild inflation and prices and wages in general rose a little. Congress raised the salary of Rangers to $100 per month and recognized the need of giving them yearlong employment. The eight hour law was passed but it applied to the unclassified workers. It wasn't until 1948 that positions below the rank of Ranger had Civil Service appointments. An attempt was made to hold work hours to eight except for lookouts and firemen.

In 1924 the Employee Classification Act was passed. This was one of the major steps in personnel management by the U.S.A. Under the provisions of this Act the beginning salary for Forest Rangers was $1800 per year, Assistant Supervisors $3000 and Forest Supervisors $4500. This compared very favorably with private industry. This law contained the first provisions for retirement and annual leave. If the Supervisor wished he could grant up to 14 days annual leave and 10 days sick leave. The law also declared if the employee was required to furnish anything more than personal items he was to be paid for it. The requirement that a Ranger must furnish a horse came to a quick end. The housing situation was still very bad.

The great depression started in 1929. I doubt that anyone who is too young to have lived at that time has any conception of the suffering and mental anguish this catastrophe created. I was a Ranger at that time and I could hire the top woodsmen in my community for $70 per month and board. In fact some offered to work for less, but $70 was the least paid. During this time government employees with their "fat" salaries became quite unpopular. Congress responded by requiring each employee to take three days a month off without pay. It was cabled the "Stagger System". Employees were supposed to take these three days off at different times so that someone else could do the work when they were off duty. This sort of an arrangement may have been possible if everyone was in the same office but it was an absurd idea as far as the Forest Service was concerned. Forest people took it for what it was meant to be, a cut, and went right on working. Another provision of this law was that there were to be no promotions in salary. With the expansion to take care of the emergency programs many people were advanced to higher positions at the same old pay. To make it worse, appointees in the emergency programs were not subject to the cut. Nothing ever hurt the morale of the Forest Service like this part of the New Deal. Fortunately, it lasted only a few years.

In the early twenties Forest Officers began using their private cars to do official business. For the use of such cars they were reimbursed at the rate of 5¢ per mile. But along with the officer's mileage statement which showed places he went and mileages, he had to submit a justification statement showing that a savings was made to the government through the reduction in time over any other means of travel. Of course, on the forest the only other means of travel was by horse so it was easy to do. This was just so much red tape. Nevertheless, these reports were required until 1927 when they were discontinued except for trips between cities. Forest officers continued to use their cars until 1935 when the Forest Service began furnishing pickups and cars for official travel.

In 1932 the work week was reduced to five and half days. The idea was to put more men to work. But so far as the Forest Service was concerned there was no increase in allotments so it did not accomplish this objective. However, it kept Federal employees' hours of work in line with private industry.

In 1935 leave was extended to cover temporary employees and it became a right.

In 1933 the first Emergency Employment programs were started, and the Forest Service took advantage of these funds to provide some badly needed housing at the Ranger Stations.

|

| A cabin near the site of the present Powell Ranger Station. The cabin was built by trapper Franz Kube and was used later by the Forest Service. The photo was taken in 1909. |

|

| Oxford Ranger Station on Elk Creek, a branch of Orogrande Creek. The structures are similar to others built in the early days of the Forest Service. Photo taken in 1921 or 1922. |

In 1945 the first Overtime Act was passed. Congress had considered this action a few years earlier but the Chief's and the Regional Offices opposed it. It was forced onto the Forest Service by the unions and other departments of the government. There was a conference of fire control officers in Washington when it became law. As Assistant Chief of Fire Control for Region One, I was present. We were called into a meeting with the Chief's Staff to discuss the new law and its impact on fire control. Chris Granger, Associate Chief started the discussion by stating, "It is inconceivable that any forest officer holding the rank of Ranger or higher would ask payment for overtime." The discussion which followed was mostly concerned with schemes to evade the law. Of course, they were not called that but that is what they were.

The eight hour law that had been in effect for about 20 years had been generally disregarded by the Forest Service except for seasonal laborers. There were many abuses. Forest employees had great pride in their work and in their ability to get things done. They voluntarily worked more than eight hours even though there was no emergency. There was great pressure to get more than eight hours work. As an example, in the personnel rating form it was asked if the employee being rated was sufficiently interested in his work to put in more than eight hours per day. There were other abuses. Conferences were often scheduled to start at 8 A.M. Monday, forcing travel on Sunday. I remember my first detail to the Regional Office. I was to report a 8 A.M. January 2. It took me all day of January 1, a holiday, to get there. Travel was slow in 1929. Another example of how business was conducted was an annual meeting of the Chief of Operation and a few others with each forest for allotment purposes. They were called allotment meetings. These men met with the Supervisors, their staff and the Rangers and to save time traveled from one forest to another. To save them laying over Sunday at some Forest Headquarters they would schedule meetings. These were the obvious violations. They were less common than scheduling work loads and deadlines that could only be met by working nights and Sundays.

Gradually overtime was accepted as a law that had to be followed. It corrected a lot of abuses and regardless of its advantages and disadvantages it is here to stay. It is the way of life over a large part of the world today.

Since 1945 there have been a number of changes in the laws that govern Forest Officer's rates of pay and fringe benefits. Pay is by two week pay periods instead of by the month. Leave has been changed and made accumulative; there is a 40 hour week; retirement age has gradually been reduced from age 65 to 55; costs of moving added and others.

PROPERTY RECORDS

The bane of early day Rangers was property records. In those days a complete annual inventory was taken of everything classed as property which included knives, forks, spoons, cups, axes, saws, keys, blankets, etc. This annual inventory was taken in the fall and all shortages had to be reported and explained on a form numbered 858. If the Ranger could not give a satisfactory reason for the shortage, he had to pay for it.

During the summer each Ranger had a bin where anything that was broken or worn out was thrown. Then when the Forest Supervisor or his assistant came around he would examine it and condemn that which was useless. The difficulty was that a lot of worn out or broken items never got into the bin. If a cook found a broken spoon or if a kettle got a hole in it they likely went into the garbage pit. If a packer found a worn out army blanket he was apt to convert it into a saddle blanket.

So the Ranger was sure to wind up paying for some items if he wasn't pretty careful with his property and clever in telling how articles were lost. A lot of time was wasted in accounting for property. I once saw a Ranger ride back to a fire camp to get three tin cups and two wash basins that the packers had missed because they were left at the spring where the camp got its water.

The submission of the 858 reports of lost property also resulted in some of the most ingenious lies ever written. If a packstring rolled (they apparently often did) or a mule drowned you could bet that they were laden with property that had disappeared. If a cabin or a fire camp burned, a lot of property went up in smoke. A boat once sank on Priest Lake and after the forest clerk had reviewed the 858 reports, he remarked that with such heavy load, it was small wonder the boat had sunk.

There was another way to get out of paying for lost property. It was a matter of a little advanced preparation. The Ranger would snitch a few items from the fire outfits and build up a surplus above what he was charged for. This was called packratting. Of course, these items had to be hidden someplace where it would not be picked up in the annual inventory. Then if the inventory showed a shortage, he would suddenly find the missing property.

This was red tape to the nth degree and everyone hated it, but it took years to get a change. Finally, in 1924 property was reclassified. It didn't do away with property accounting but it did grant a great measure of relief by making inexpensive items expendable.

This didn't mean that troubles with property were all solved. One time Procurement and Supply (P&S) bought some saws. These saws were marked "Sanvig-made in Sweden". P & S claimed they got them at bargain prices and likely they did. But even if they got them free, they got beat. They were the thickest and heaviest saws I ever saw. No one would use them, not even the Swedes. This may be the reason they were exported to America.

Since no one used these saws, they never wore out and the Ranger couldn't get them condemned because they were in good condition. But where there is a will, there is a way. The 25 man outfits had good saws, so every time a fire outfit came on the district from the Spokane Warehouse, the Ranger would trade saws before he sent it back. P&S set up a howl and the result was an agreement to condemn the Sanvig saws.

COMMUNICATIONS

One of the greatest handicaps to the early day Forest Ranger was lack of an adequate communication system. Up to 1910 there was no means of transmitting messages faster than by saddle horse. The need for better communications was so emphasized during the severe 1910 fire season that the Forest Service embarked on a telephone line construction program. It also equipped lookouts with heliographs.

The heliograph was an instrument for conveying messages by code using mirrors and a shutter to flash rays of light from the sun. It was not very effective for Forest Service work because of its limitations. It could not be used at night; cloudy weather made it inoperable; many men were not patient enough to learn the code; it took a lot of time to send a message; the instrument had to be reoriented almost continuously due to the earth's rotation; it could not penetrate smoke or haze. It was a little better than nothing for some messages did get through.

The Forest Service recognized these handicaps and set out to establish a telephone system that would link every lookout to a Ranger Station and every Ranger Station to the Supervisor's office. The first of these lines were made of No. 12 galvanized wire hung on solid insulators spiked to trees. The maintenence on these lines was slow and expensive because every time a tree fell across the line it broke and frequently it tore off the insulator.

In about 1911 Ranger William Daughs invented the split tree insulator. He whittled the first model out of a piece of Douglas fir bark. It was in two parts that were wired together so that the telephone line rode in an oval hole in the center. The ends of the wire that bound the insulator together were then bent into hooks that hung on a staple driven into a tree at the proper height.

This insulator let the telephone line ride free so that when a tree fell across it the line seldom broke. Slack wire would be pulled from both directions and let the line go to the ground with the falling tree. If more than one tree fell across the line then the insulator unhooked from the staple and came to the ground. The maintenance men cut the windfall off the line and replaced the insulator to the staple. This insulator was immediately adopted and at this same time No. 9 galvanized wire, which was much stronger than No. 12, became the standard. These innovations made telephone line maintenance much easier and cheaper but it still required a lot of tree climbing.

By 1915 there was a telephone line to each Ranger Station except the Fish Lake District on the Lochsa. A few lookouts also had lines. Chamberlain Meadows, Elk Summit, and the North Fork Fish Lake Districts were connected by lines to Montana.

By 1917 almost all lookouts and Ranger Stations in use at that time had telephones.

|

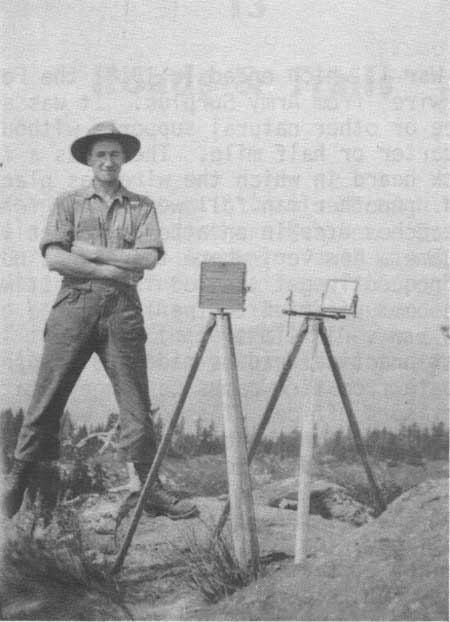

| James C. Urquhart atop a peak in 1917 with a Forest Service heliograph. |

|

| Omer Snyder and Ralph Teed constructing telephone line near Cook Mountain in 1916. |

Following World War I, which ended in 1918, the Forest Service was abbe to get "outpost wire" from Army Surplus. It was an insulated wire which was hung on tree or other natural supports without insulators. It came in rolls of a quarter or half mile. There was a frame that went on a man's back like a pack board in which the wire was placed so that it reeled out as the man walked. Another man followed with a forked stick and placed the wire over tree branches etc. in an attempt to get it off the ground and above wandering big game. However, where there were not tree branches to hang it on game did frequently get tangled in it. It was a big help especially in providing communication to trail and fire camps.

In 1933 the first practical radios made their appearance. These sets were used to communicate from fire camps to Ranger Stations and from Ranger Stations to the Supervisors Office. These sets were very temperamental. Special training in their use was necessary to keep them in operation. On fires "ham" operators were hired to keep them in operation.

The conversion of the communication system from telephone lines to radios was very gradual covering the 40 year period from 1934 to 1975. Starting in 1934 a number of forests and Ranger Districts were combined which cut down the need for telephone lines. Then when smokejumping became practical a number of fireman and lookout stations primarily used in fire suppression became out of date. The largest change came when air detection replaced lookout detection. This started on the Bob Marshall Wilderness area as an experiment in 1944 and spread to all forests. The transition was so slow that telephone lines gradually fell into disuse without being removed from the ground. The wire was a hazard to game which often became entangled in it. It took a special effort to get the wire picked up and out of the woods but sections of old telephone lines can still be found.

After World War II, radios were much improved and the Forest Service moved rapidly to the use of radios. At the present time the Clearwater has none of its own telephone lines. The last one was taken down in 1975.

For communication the Clearwater Forest now has an extensive radio system and uses the modern commercial telephone system.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

clearwater/story/chap12.htm Last Updated: 29-Feb-2012 |