|

The Clearwater Story: A History of the Clearwater National Forest |

|

Chapter 13

Roads & Trails

The Nez Perce Indians had two main trails through the Bitterroot Mountains. One was the Lolo Trail or Northern Nez Perce Trail and the other was the Southern Nez Perce Trail. The Lolo Trail was discussed in some detail earlier. The Southern Nez Perce Trail went through the Nez Perce Forest. The Indians also had two other trails which bordered the Forest and went through a part of it. From these trails they had branch and connecting trails, making it difficult now to say which were Indian trails or the work of early prospectors.

One of the Indian trails went up the Middle Fork of the Clearwater to Lowell, then up Coolwater Ridge past Old Man Lake, Shasta Lake, End Butte, Fish Lake, Lost Knife Meadows, Army Mule Pass, Saturday Ridge, Friday Pass, Elk Summit, Big Sand Lake, Blodgett Pass and down Blodgett Creek.

Another Indian trail started near Clarkia and followed the St. Joe-North Fork Divide. It took a small short cut by crossing the Little North Fork at the mouth of Rocky Run. I am not sure what course it took when it reached the vicinity of Chamberlain Meadows, but it did go to the Clarks Fork in Montana.

There was an Indian trail from Orofino to Quartz Creek that the road today follows fairly closely. At Quartz Creek it was joined by a trail from Weippe. From Quartz Creek it crossed to Reeds Creek in the vicinity of the mouth of Deer Creek. From Deer Creek it crossed to the meadows of Washington Creek. At one time I understood that it went up the ridge between Beaver and Scofield Creeks, but I find that this trail was built by miners. From the lower part of Washington Creek Meadows it went to Deadhorse, Sheep Mountain, Eagle Point and crossed the North Fork near the mouth of Skull Creek, then up Indian Henry Ridge to Chamberlain Meadows.

Up the Lochsa there was an Indian trail that took off from the Lolo Trail about two miles east of Indian Post Office and came to the Lochsa River near the mouth of Warm Springs Creek. This is the trail the Carlin Party took in 1893.

Another old trail, followed by Shattuck in 1910, went from Hoo Doo Lake to Tom Beall Park and down the ridge the road follows today. It crossed the Lochsa River about a mile below Powell Ranger Station.

The Indians had a trail from Cayuse Junction to the Blacklead country and on north up the main Bitterroot divide as far as Kid Lake and likely to Fish Lake.

There is another old trail which may have been an Indian Trail. However, it could be that it was built by the Northern Pacific engineers who surveyed a railroad location in 1870 from Superior, Montana over the summit at Goose Lake and down the North Fork to Ahsahka. This trail ran from Pierce over Elk Mountain to the Bungalow and went over Pot Mountain and Fly Hill where it joined the Indian trail at Birch Ridge. This old trail was also used by Moose City miners.

No doubt there were many branch trails leading off from these old Indian trails, but their location is unknown.

In 1860 gold was discovered at Pierce. A gold rush followed and prospectors followed established travel routes where practical, but they hacked their way through the country and established many more trails and improved some of the older routes. For example, a trail called the Moscow Bar Trail was built following from what is now Headquarters east along the divide between Beaver and Washington Creeks to Deadhorse. From there it went to Moscow Bar, reaching the river at the mouth of Deadhorse Creek.

A trail was built into the Blacklead country from Montana connecting with the Indian trail to Cayuse Junction.

Following the Indians and the miners, the Forest Service took over. For a number of years Forest Service trail construction was very slow. From 1902 to 1907 the Land Office surveyors sectionized several townships within the Forest and opened up a few routes. One went into the Cook Mountain country going in from Beaver Saddle over Leanto Ridge.

In 1904 Howard B. Carpenter surveyed the State line between Idaho and Montana. To move his survey party through the mountains and to keep them supplied, he cut out a trail that in a rough way followed the Bitterroot Divide. This old trail, with only minor changes, is in use today.

In 1908 and 1909 the railroad surveyors opened a trail through the Lochsa with some branches to the Lolo and Coolwater Divide trails. The railroad survey did not build a trail through Black Canyon. This section of trail was built by the Forest Service in 1927.

Following the fires of 1910, the Forest Service received appropriations for trail construction. Trails were badly needed. A table of mileage on the Forest, prepared in 1916, shows that the Clearwater had a total of 160 miles of trail. This did not include trails on the Lochsa which was not part of the Clearwater at that time.

The job of constructing an adequate trail system was tremendous and the Forest Service set to work with vigor. Every Ranger had at least two and some had more crews building trails. By 1927 trails were completed up almost every major drainage and up every ridge of any importance. In fact, the Forest Service had developed a mania for building trails. Even though a good network of trails was completed by 1927, it was decided to build even more and cheaper trails by building what was called "way trails"; any trail a loaded mule string could get over. As early as 1925 some Forest officers suggested diverting the money to road construction, but such ideas were quickly suppressed. Trail construction was pursued with vigor up to 1933, but a few road jobs that were easy to construct were started in 1929.

With road construction in full swing in 1933, all trail construction stopped. Many "way trails" were never maintained.

|

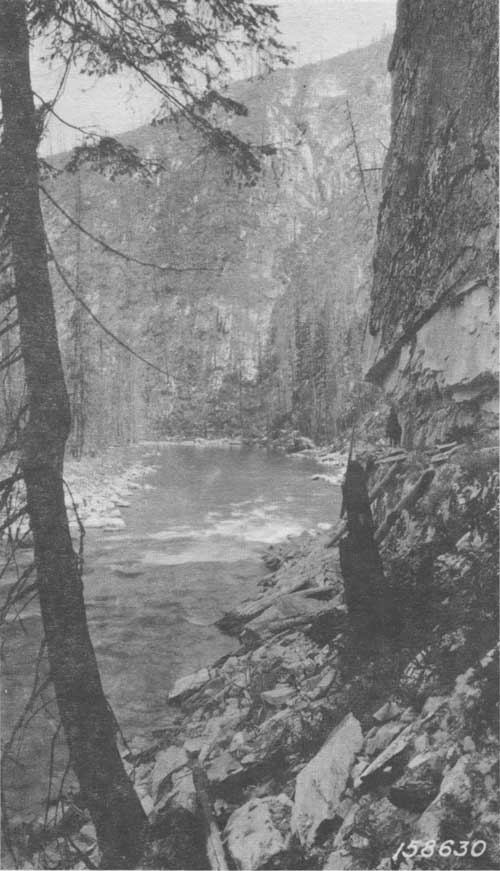

| 1921 photo of the trail along the North Fork of the Clearwater at Castle Rock. |

|

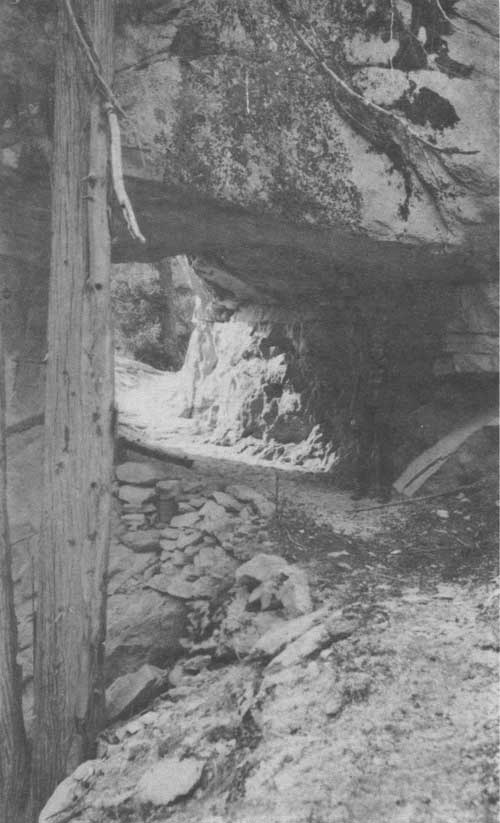

| A tunnel along the North Fork trail below Bungalow. Construction of the North Fork Road in 1955 wiped out the tunnel. |

In 1939 the Forest Service developed aerial delivery of supplies by parachute and in 1940 men were being parachuted to fires. This made many miles of trail unnecessary. Way trails were almost entirely abandoned and many more miles of trail became useless except for hunting.

The helicopter next came into use, making still more miles of trail of no practical value except for harvest of game.

THE LOLO TRAIL

The Lolo Trail, strictly speaking, is the travel route from Lolo, Montana to Weippe, Idaho. However, the route has had a number of names and its termini have been changed from time to time.

The Indians traveled the Lolo Trail before the coming of white men. The Nez Perce name for this route is Khusahna Ishkit or buffalo trail. It was one of the two main routes of travel for the Nez Perces to the buffalo herds in Montana and Wyoming. The other route was further south and first became known as the Southern Nez Perce Trail and later as the Nez Perce Trail.

Some writers state that this trail is thousands of years old. However, the studies I have made indicate that, while part of it is very old, a large part of it has been used only a few hundred years, probably after the Indians of this locality acquired horses (about 1700 A.D.). One of the old sections of the trail is from Lolo, Montana to Wendover Creek. Lewis and Clark found this part of the trail much deeper than the mountain section. It was used by the Salish Indians in reaching the salmon fishing areas around Powell Ranger Station, there being no salmon in the waters of the Clarks Fork River. Another feature of the Lolo Trail that supports my theory is that, at the time of Lewis and Clark, the trail ran from meadow to meadow. Apparently this was to insure horsefeed, when a much shorter route with fewer changes in grade could have been developed.

The Lolo Trail was a formidable obstacle to the early explorers, trappers, hunters and soldiers. It is often described as precipitous, boulder strewn and over high rugged mountains. It is none of these. The highest point on the trail is 7035 feet at Indian Post Office, which is not high as mountains go. Boulders are rare and there isn't a single cliff to be seen in the entire route.

What then, made this trail so difficult to cross? There are a number of reasons.

First, the area is densely timbered. Each year dead trees rot off and fall, others are blown over by the wind or broken off by snow. Even one year's crop of down trees would make travel difficult, and the accumulation of several years made travel slow and dangerous to horses.

Second, snow comes early and melts late. Snow may fall any month, but winter snow may come as early as October and leave sometime between July 1 and August 1.

Third, there is little game along the Lolo Trail. Game animals do cross this divide, but prefer the basins at the heads of streams for their feeding grounds.

Fourth, the ridge this trail follows is not a hogback but a series of mountains and deep saddles. The divide is cut by six major saddles and many more small ones so that the traveler is continually dropping into deep saddles and then climbing out the other side. For example, the elevation at Sherman Saddle is about 4800 feet and Sherman Peak 6500, a climb of about 1700 feet in three miles.

General Howard's description of the Lolo Trail illustrates this point. "It does not appear far to the next peak. It is not so in a straight course, but such a course is impossible. 'Keep to the Hogback'. That means that there usually is a crooked connecting ridge between two neighboring heights and you must keep on it. The necessity of doing so often made the distance three times greater than by straight lines; but the ground was so stoney, too steep, the canyon too deep to attempt the shorter course. Conceive this climbing ridge after ridge, in the wildest wilderness, with the only possible pathway filled with timber, small and large, crossed and criss-crossed; and now, while the horses and mules are feeding on unnutritious wire grass, you will not wonder at only sixteen miles a day".

Fifth, the Clearwater mud. The country is blessed with a deep fertile soil that becomes slick and deep mud when wet.

In 1897 President Cleveland proclaimed the Bitter Root Reserve. It included territory in both Idaho and Montana. The Lolo Trail was within its boundaries. After a number of changes, the Lolo Trail fell within the boundaries of the Lolo and Clearwater National Forests in 1907, and it has been there since that time.

Ever since the forest was created, the Lolo Trail was one of the main travel routes for the Forest Service people. It had been in continuous use since the days of General Howard, when it was last cleared of windfalls, but travelers had gone over or around windfalls where possible. In 1907, the Clearwater and Lolo Forests received allotments for opening the Lolo Trail. They started from both ends. The Lolo started at Lolo Hot Springs which was the end of the road in Montana. The work on the Lolo was under Dwight L. Beatty. I am not sure, but I believe he was the Ranger.

The work on the Clearwater was under Ranger John Durant. He spent considerable time on the job himself, but he hired Ralph Castle as foreman, Walter Sewell as cook, and Charley Adams as packer. There were a number of axemen and sawyers in the crew. They started in May and set up their first camp at a small creek on the old road my father, C.W. Space, built in 1897 or 1898 to take machinery to the old Pioneer mine. They were almost immediately subjected to a snow storm. They named the creek Siberia Creek and so it is today.

From Siberia Creek they built an almost level trail to the forks of Lolo and Yoosa Creeks, thereby eliminating a very muddy section of the old trail that went down Lolo Creek and over a low hill to Musselshell Meadows.

From the forks of Lolo and Yoosa Creeks they were on the trail built by Bird and all they needed to do was remove the windfalls and brush that had accumulated in the thirty years since General Howard went over it. Of course, there was plenty to do, but it was much faster after they did not have to dig a tread. The crews met near Indian Post Office. Thereafter, the Forest Service maintained the Lolo Trail annually and there was little or no change until road construction started at Lolo Hot Springs in 1925 and reached Powell in 1928.

To replace the Lolo Trail, a single-lane road with turnouts was started in 1930 and sections built from both ends each summer, the crews meeting in 1934. A celebration was held at Indian Grave to commemorate the event. This was, and much of it still is, a rough, steep and crooked road. For the benefit of the numerous parties I have taken over the Lolo Motorway, I wrote a little jingle. It goes like this:

"This road is winding, crooked and rough,

But you can make it, if you are tough.

God help your tires, God help your load,

God bless the men who built this road."

In addition to building a motorway along the Lolo Trail, the Forest Service had located and signed many points of historical interest. Elers Koch, at one time Supervisor of the Lolo National Forest and later Assistant Regional Forester in charge of Timber Management, did much to locate the campgrounds of Lewis and Clark. He worded the first signs that were installed in 1939 and took part in seeing that they were properly placed.

When I became Supervisor of the Clearwater in 1954, I revived the effort to locate the camp sites of Lewis and Clark and other points of interest along the Lolo Trail. Practically all camps are now located and many are noted with historical markers.

I first crossed the Lolo Trail in 1924. I have no idea how many times I have been over it in the past 50 years. I have walked it, ridden on horseback and traveled by car. I have slogged over it in the rain and mud, fought fires along it in summer heat, dust and drought and been caught in some of its early snowstorms. I have seen it change from a trail to a road and highway, and a large part of the area that it traverses from a sea of snags, following the disastrous fire of 1919, to a beautiful forest.

The Lolo Trail has exacted its measure of toil, pain suffering and death. Yet it is a beautiful country with a lot of history. In fact so much history that in 1965, it was designated a National Historical Landmark.

ROAD CONSTRUCTION

Up to 1920 the Clearwater Forest had practically no roads. There was a rough road to the Oxford Mine on Elk Creek built by the mining company in 1902. There was also a road to the Pioneer Mine from Musselshell built about 1897. This road soon became almost impassable beyond the Musselshell Ranger Station. Another road of sorts ran up Swede Creek across a hill to the mouth of Greer Gulch. There were also some miners roads around French Mountain. The road up the Middle Fork ended at the Middle Fork (No. 1) Ranger Station. All these roads ended at or near the Forest Boundary. They were exceedingly rough, muddy and steep. They were passible only during the summer months.

Following the fire season of 1919, which ranks second to 1910 in area burned, the Forest Service appealed to Congress for money to build some roads. This request was granted, but since the Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) was the road building agency of the United States, the money was alloted to them. The BPR let contracts to Morrison-Knudson (this was a small outfit then) to build roads to Pete King in 1920 and to the Bungalow in 1921. These roads were typical of that day. They were nine feet wide and followed the contour of the hills. They were "crooked as a snake" and if you met some other vehicle it was a problem to pass, but you didn't meet many people. The Forest Service soon found that it was necessary to widen these roads.

The Forest Service wanted to get into road building and something of a hassle arose between them and the BPR over who should have the authority. The BPR was dominant until about 1928 when the Forest Service assured the BPR and Congress that it was interested in building low standard roads which were termed "Motor Ways" or "Truck Trails". It agreed that the BPR was to be the agency in building highways. The Forest Service then began building roads. These roads were not designed. All that was used was a center line location. The roads under the CCC Program were all truck trails. The primary purpose of these roads was for fire protection and they were well worth the cost. The Forest Service did not anticipate that these roads would be used much by the public. In this, they were greatly mistaken. Traffic built up on some of these roads far beyond what they could carry without rutting them deeply. This was especially true in the fall when the hunters took to the woods when they were wet and easily damaged. Waterbars and open top culverts came into use but they were never very satisfactory.

The CCC ended in 1942. Since then the only road built by Forest Service crews was the road from Pierce to Musselshell. It was a war emergency project to open up timber needed for the war.

Following the war all roads, except those in campgrounds, have been built either under contract or as part of a timber sale agreement. Some of these roads were designed by the BPR but most were by Forest Service Engineers.

The Clearwater Forest now has a total of 2,320 miles of roads. A list of all the roads and the date of construction would be too long to include here. I will list only those of major interest.

| ROAD | DATE COMPLETED |

| Pete King Ranger Station | 1920 |

| Bungalow Ranger Station | 1921 |

| Weitas Guard Station | 1933 |

| Road to Elk Summit | 1933 |

| Lolo Trail | 1934 |

| Road up the North Fork through to Superior, Montana was built from both ends and finished | 1935 |

| Tom Beall | 1935 |

| Smith Creek-Pete King Creek | 1953 |

| Glenwood-Eldorado | 1953 |

| Diamond Match Road (Superior-Cedars) | 1954 |

| Cold Springs | 1955 |

| Eldorado Musselshell | 1955 |

| Eldorado | 1960 |

| Down River | 1967 |

| Beaver Creek | 1967 |

THE WASHINGTON CREEK BRIDGE

At the mouth of Washington Creek there is a fine, heavy duty bridge across the North Fork of the Clearwater River. The peculiar thing about this bridge is obviously a more elaborate structure than is needed for the traffic it carries, the question arises as to why it was built.

In 1953, Assistant Regional Forester, R.U. Harmon, made an inspection of the Clearwater National Forest. One of the points covered in his memorandum of inspection was the road situation in the area tributary to the North Fork downriver from Orogrande Creek.

At the time the situation was as follows. The Forest Service had a road on a good grade from Pierce to the mouth of Orogrande Creek (The Bungalow), but most of it was too narrow for log hauling. This road ran down river to Pack Creek. Potlatch Forests, Inc. had two logging railroads extending out of Headquarters. One ran down Washington Creek to a log landing at the mouth of Lodge Creek. The other ran up Alder Creek and down Beaver Creek to the mouth of the South Fork of Beaver Creek. The Forest Service had roads to Canyon Ranger Station and Washington Creek with connecting links, but these were one lane roads or motorways that went over Elk Mountain or Bertha Hill. They were narrow, crooked, steep and were passable only during the summer months. There were some good logging roads on National Forest lands around Sheep Mountain and Deadhorse but these ended at the P.F.I. railroad landings.

Of course, this situation was very much to the advantage of P.F.I. since no other company could bid on National Forest timber in that area. It was greatly to the disadvantage of the Forest Service, not only because it limited bidding for timber, but also because if repeated timber sales were made as in the past, the forest would eventually have some very good roads on the forest that could be reached only by going over some low classed roads. Mr. Harmon pointed out this situation in his memorandum of inspection and urged that a better system of roads be planned.

In the spring of 1954, I came to the Clearwater as Supervisor just in time to sit in on the review of Harmon's inspection report by the Regional Forester and his staff. There was a lively discussion. No one disagreed with the idea of a better road system, but there were a lot of different ideas on what to do about it. It was a difficult problem involving a large expenditure of money.

Finally, I proposed that Forest personnel make a thorough investigation of the problem and come up with a report and recommendations on what the best transportation system should be. I promised a study of all their proposals and any others we could think of and a comparison of the costs, advantages and disadvantages of each. The Regional Forester, Percy (Pete) Hanson, agreed to this proposal and gave me a year to make the study and report.

I returned to the Forest and immediately organized my staff to get going on this difficult but interesting problem. The organization set up was for my Timber Staff Assistant, Sam Evans, and his helpers, but mainly Robert Spencer, to compile the information on timber volumes by logging units. The Forest Engineer, Bernie Glaus, and his assistants, particularly Norman Allison, were to study the possible road routes and estimate the costs of the construction and hauling. I was to coordinate the work, assist with difficult situations and pull the data together for the final report.

We started out by listing every route for investigation that had the least promise of being feasible, but it soon boiled down to three routes with possible combinations and variations. These were the Orogrande, Washington, and Beaver Creek routes.

One variation of the Orogrande route we studied was the possibility of staying on the south side of the river from the Bungalow down to Washington Creek and then bridging the river. This would have permitted use of the old bridge at the Bungalow for administrative travel since it was inadequate for log haul and thus saved the construction of one bridge. This route proved to be more costly than the north side because a one lane road had previously been built to Pack Creek.

During the summer of 1954, I rode the trail from the Bungalow to Canyon Ranger Station. I examined all the blocks of timber and checked the road possibilities and satisfied myself that the estimated timber volumes were there. I made my last trip in October to Wallow Mountain (I took annual leave because I shot an elk).

During the fall of 1954 we assembled and analyzed our data. We found that the Washington Creek route was the least acceptable. One thing against this route was the steep grade from the river to Lodge Creek.

This left the Beaver and Orogrande Creek routes. We found that it would be cheaper to haul out by way of Beaver Creek, but the P.F.I. logging railroad occupied the only practical location. To take this route would also omit any road from the mouth of Orogrande Creek down river to the vicinity of Quartz Creek. We had no way of placing a value on this section of the road for administrative purposes, but after considering the small difference in the cost of the two routes, the difficulty of acquiring a suitable right-of-way for the Beaver Creek route and the administrative advantages of having a road downriver we recommended the Orogrande route.

|

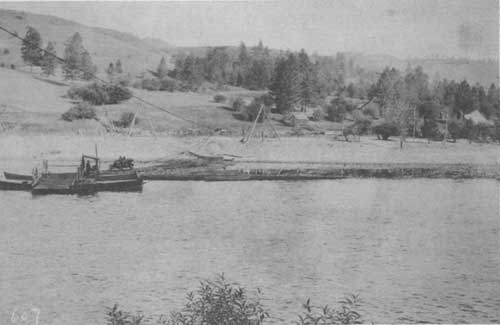

| Constructing Washington Creek Bridge across the North Fork in 1962. |

I presented the forest's report to the Regional Forester and his staff. I received many compliments on the work we did, and the decision was made to follow the forest's recommendation. The first contract on the downriver road was let that spring.

The road work progressed as fast as finances became available. The road to the Bungalow was being rebuilt and a bridge was constructed across the North Fork at the mouth of Washington Creek in preparation for a connecting link between the roads in lower Washington Creek and the main road along the river.

Times changed and so do logging methods. The P.F.I. had operated a system of private logging railroads for years but they found that it would be cheaper to do away with their railroads and use logging roads instead. They, therefore, decided to do away with their Beaver Creek railroad and replace it with a logging road. Since the Forest Service was interested in a road on this location it was proposed to build the road on a cost sharing basis. An agreement was soon signed to that effect. This then became the main road to the Canyon area. It also made the proposed connecting road from Lower Washington Creek to the river unnecessary. The bridge across the river was then left without filling its original intent.

THE LEWIS AND CLARK HIGHWAY

During the mining days of the 1860's the people of Lewiston clamored for a road to Montana by way of the Lolo Trail. This route was impractical and the proposal was dropped.

A railroad was surveyed from Kooskia to Lolo in 1908 and 1909 and, although it was never built, out of this survey came the idea for a road following the same route. Anyone who would think of such a thing in 1908 had to be a dreamer. Who the dreamer was is unknown. The idea caught on around Kooskia and Kamiah but gained little headway until 1915 when the Forest Service investigated the proposal. I am unable to find a copy of the report and recommendations on this project, but they must have been favorable because in 1916 this road was designated a state highway and given the name of "The Lewis and Clark Highway".

Before 1919 there was a ferry crossing the Middle Fork just above Kooskia. It was replaced by a bridge in 1919. This was the first work done on the Lewis and Clark Highway. However, prior to 1919 there was a wagon road built by settlers up the Middle Fork as far as Smith Creek.

In 1920 a narrow road was built to Pete King Ranger Station. It was nine feet wide and was reconstructed twice before the highway was finally completed.

Up to this time, interest in the highway was pretty much confined to the people of the Kooskia and Kamiah localities and the Forest Service. But the use of cars and trucks was expanding rapidly and increased the need for through highways. Wider interest in a road from Lewiston east soon developed and that city got into the act in 1921. In December of that year the Lewis and Clark Highway Association was organized with headquarters at Lewiston.

|

| Building the road up the Lochsa to Pete King in 1919. This road was later upgraded and eventually extended across the Bitterroots into Montana. It is the Lewis & Clark Highway (U.S. 12). |

|

| Ferry across the Middle Fork of the Clearwater just east of Kooskia in 1918. A bridge was started at the site the following year. |

Mr. Seaburg was its head man, but Mark Means also took a very active part. The first meeting of this association was at Lewiston in January 1922 and was attended by representatives of Chambers of Commerce and other organizations from as far away as Missoula.

The Lewiston meeting was followed by another Chamber of Commerce meeting in Missoula. At this meeting Governor Dixon was the speaker. His talk was a big boost to the highway; he covered the need for the highway and announced Montana's approval and support of the project.

With all the support and enthusiasm that had been generated it appeared that the highway could soon be built. In 1923 the survey was extended beyond Boulder Ranger Station. A river crossing was planned near Old Man Creek and another near the present Lochsa Ranger Station. The decision to move the Ranger Station from Boulder Creek to the present site of the Lochsa Work Center was partly based on the assumption that there would be a bridge across the Lochsa at this point. The highway was extended to Deadman Creek in 1923; it was a narrow road that was later reconstructed.

In 1924 Grangeville and the Northwest Mining Association opposed further expenditures on the Lewis and Clark Highway until a water grade road was built to Elk City. However, the road was extended to Bimerick Creek. This section was also reconstructed later.

In 1925 it was decided to build a road from the east to Powell Ranger Station before doing any more work on the western end. The road reached Powell in 1928. It was a low quality road that was later rebuilt, although parts of the old road were used.

In 1929 the State Highway Department yielded to pressure to place money on other roads ahead of the Lewis and Clark Highway. At this time the attitude of the Forest Service changed. With the antagonistic attitude of the Forest Service and only local support in Idaho, money for this project was not forthcoming. The ends of the road stayed at Bimerick Creek and Powell Ranger Station from 1928 to 1941.

There was some work accomplished during this period, but compared with the total job it seemed small indeed. An aerial road survey was made of the route in 1931. It was the first such survey in the U.S.A. The state did the best it could by using convict labor starting in 1935. A camp was built at the mouth of Canyon Creek and prisoners were employed in widening the road that had previously been constructed. A narrow road was built to Wild Horse Creek. This camp was later used to house Japanese internees who also worked on the road. But prisoner work was not very effective, mainly because not enough heavy equipment was available.

Times changed. The Forest Service again became favorable to the project, partly due to pressure from the public, but mainly because the road was needed for National Forest Administration. In 1941 the Regional Forester stated that he favored the road. That summer the Bureau of Public Roads surveyed the entire project. The Forest Service furnished the packers and pack stock.

Considerable pressure was continually exerted by the Lewis and Clark Highway Association to get the highway through. At one time it was proposed to punch a low-grade road through with a bulldozer under the theory that the traveling public would demand that the road be brought up to standard. The Forest Service strenuously opposed such a move. Regional Forester P.D. Hanson publicly went on record against such a proposal at a meeting in Lewiston in 1945. He contended that such a road would be unsafe and a waste of money. The Idaho State Highway Board agreed.

By 1948 funds were available and construction was resumed at the rate of two or three miles per year. This was not fast enough to satisfy interested parties, so all sorts of publicity stunts were used to call attention to the need for a speeded-up program. As an example, in 1952 a party headed by Harold Coe of Clarkston hiked through the unfinished section through the Lochsa Canyon. They were not woodsmen and in some places lost the old trail and had to beach it over the rocks along the river. It took them four days and some members of the party were exhausted.

In 1955 the Idaho Legislature passed a law which made a toll road legally permissible. Thereafter, a group known as the Turnpike Association was organized to study the possibility of completing the remaining section as a toll road. A study was made but was reported unfavorable.

In 1957, a trek through the canyon was organized, culminating with a meeting at Boulder Flat. The old trail along the river had not been repaired after the heavy damage caused by the 1948 flood. It was not practical to ride through all the canyon. The party went down the river to the cable bridge, then over Mocus Point and down Boulder Creek. It was an enthusiastic meeting attended by about two thousand people.

In the fall of 1957, a U.S. Senate investigation was held at Lewiston by Senator Gore from Tennessee. The Lewis and Clark Highway received such support that the legislature appropriated four million dollars to complete the road. There really was no need for further publicity but another trek through the Lochsa was conducted in 1958. It was a lot of fun, but the goal had been reached and the trek and meeting were pointless. There were proposals to have another trek in 1959, but I told them that I would not accompany them. I had walked and rode over the route several times and from then on I was going to ride in a car.

In October 1959, U.S. Senator Dworshak of Idaho was escorted through the uncompleted section of the road in a four-wheel drive vehicle supplied by the Triangle Construction Company which opened up the last section of the highway. I rode through with the Senator. Similar vehicles had gone through as early as July 1959.

In 1960 the section from Powell to Lolo Pass was widened, straightened and oiled and some minor improvements were made in 1961 and 1962.

In 1962 the road was completed and a big dedication ceremony held at Packer Meadows. About ten thousand people were present including such dignitaries as Forest Supervisor Ralph Space, Regional Forester Boyd Rassmussen, Chief Forester Edward Cliff, Governor Babcock of Montana, Governor Smylie of Idaho, Senator Church of Idaho and Senator Gore from Tennessee who was the main speaker. Ray McNichols of Orofino served as master of ceremonies and the two governors sawed a log in two instead of cutting the usual ribbon.

Construction of Lewis and Clark Highway by Years.

| 1919 | Bridge built across the Middle Fork of the Clearwater River. |

| 1920 | Road built from Kooskia to Lowell. |

| 1923 | Road built from Lowell to Deadman Creek. |

| 1924 | Road built from Deadman to Bimerick. |

| 1925 | Eastern end built to Crooked Creek. |

| 1926 | Crooked Creek to four miles east of Powell Ranger Station. |

| 1927 | Crooked Creek bridge built. |

| 1928 | Road completed to Powell Ranger Station. |

| 1930 | Preliminary survey of entire route. |

| 1931 | Aerial survey made of proposed route. |

| 1935 | Middle Fork of Clearwater Bridge built. |

| 1941 | Complete survey of entire route. |

| 1941 | Western end extended from Bimerick to Wildhorse Creek. |

| 1948 | Road built from Powell Ranger Station to Papoose Creek. |

| 1950 | West end extended from Wildhorse to Beaver Flat. |

| 1951 | West end extended to Fish Creek. |

| 1951 | East end extended to Wendover Creek. |

| 1953 | East end built to Squaw Creek. |

| 1954 | West end constructed to Five Islands. |

| 1955 | West end built from Five Islands to Bald Mt. Creek. |

| 1956 | West end extended from Bald Mt. Creek to Stanley Creek. |

| 1956 | East end built from Squaw Creek to Warm Springs Creek. |

| 1957 | Road oiled from Kooskia to Syringa. |

| 1958 | Section built from Stanley Creek to Eagle Mt. Creek. The section near Old Man Creek widened. |

| 1958-59 | From Syringa to Pete King widened and oiled. |

| 1958-60 | From Colgate to Eagle Mt. Creek constructed. Closed the gap. |

| 1959-60 | The section from Powell to Lolo Pass widened and straightened. |

| 1962 | In August Highway officially opened and dedicated. |

|

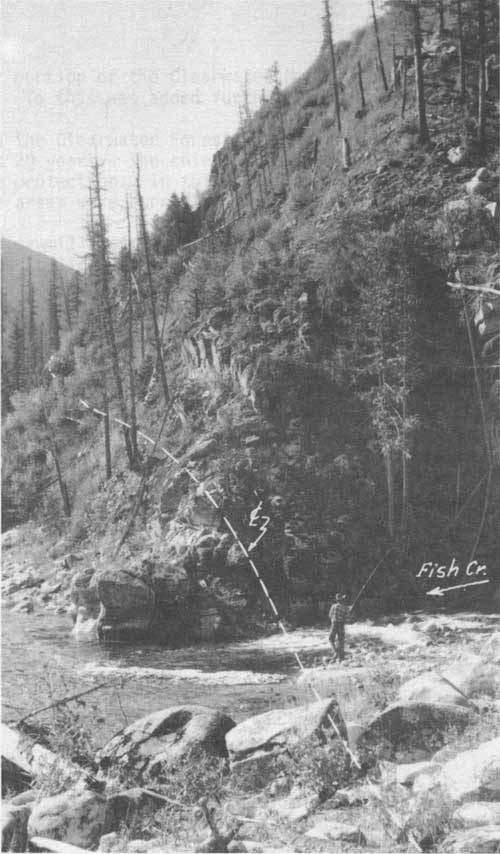

| Where the Lewis and Clark Highway crosses Fish Creek. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

clearwater/story/chap13.htm Last Updated: 29-Feb-2012 |