|

The Clearwater Story: A History of the Clearwater National Forest |

|

Chapter 14

Timber Management

The major portion of the Clearwater National Forest lands was withdrawn in 1897. To this was added further withdrawals up to 1908.

So far as the Clearwater Forest was concerned, no timber sales were made for about 20 years. The chief concern of the Forest Service for many years was fire protection. In this activity the Forest was not very successful. Huge areas were burned in 1910, 1919, 1929 and 1934.

In 1912 a sawmill was established at Weippe and an inquiry made concerning the possibility of a timber sale in the Musselshell country. There was talk that a railroad might be built to Weippe. The Northern Pacific Railroad Co. had surveyed a possible route up Fords Creek in 1909.

Following this inquiry the Forest Service organized a cruising party early in 1913 and set out to cruise what was known as the Musselshell country, which was actually all of the Lolo Creek drainage within the forest. So great was the rush to get the job done that it was started in March with five feet of snow on the ground.

According to K.D. Swan this party, in addition to himself, consisted of the following men:

| Fred R. Mason | Chief of party |

| R.V. Buckner | Traverseman |

| Shaw | Cruiser |

| Miller | Cruiser |

| Eldon Myrick | Cruiser |

| Lloyd Fenn | Cruiser |

| Alfred Hastings | Cruiser |

| Clark Miles | Cruiser |

| James Yule | Draftsman |

| Charlie Farmer | Checked work from the Regional Office |

| Robert Gaffney | Cook |

Many of these men later had long careers in the Forest Service. This crew not only cruised the timber, but made a contour map, which proved very accurate.

The timber sale was advertised in July 1914 for 602 million board feet and 300,000 cedar poles. This would have been an enormous sale. I doubt Region One has ever made one so large.

The advertised prices were as follows: white pine, $3.50; Ponderosa Pine, $2.00; Lodgepole pine, $1.50; spruce, $1.50; grand fir, $.75; and others at $.50 per thousand board feet. The average price was $2.05 per thousand board feet.

The logging plan contemplated the construction of a railroad up Fords Creek to Weippe with branch lines to the Lolo-Musselshell sale. Cutting was to be clear cut and plant.

No bids were received. The mill at Weippe was discontinued in 1918.

In 1921, U.S. Swartz cruised the Orofino Creek drainage. This survey was made upon the application of Messrs. Baily and Watters, miners in that locality. They planned to establish a sawmill at Pierce. The sale was never made. The cruise showed 48 million board feet of timber, 21 million of it white pine, in the Orofino Creek drainage. It cost three and one eighth cents per acre to make the cruise.

An extensive reconnaissance of the forest was conducted in 1921 and 1922. The primary object of this survey was for fire control. However, it did produce a good map of the timbered and burned areas. It also showed that there were large areas of burn that were not reproducing.

In 1923 and 1924 there was further reconnaissance of the merchantable areas to determine what volumes they supported. The total volume of timber on the Clearwater Forest at that time was estimated to be 4,200 million board feet. That did not include the Palouse District or any of the Lochsa and Middle Fork drainages which were not then a part of the Clearwater. Today's cruises show that those estimates were conservative. So the Clearwater, even with its large burns, had a sizable volume of timber.

The first timber sale on the Clearwater, so far as I can determine, was for cedar poles on Smith Creek. These poles were cut in 1916 to 1924 and driven down the Middle Fork to Kooskia.

The next sale was also for cedar poles. It was to Chapin on Rat and Yakus Creeks in 1929.

Sales then dribbled along on an intermittent basis up until 1939. Since 1939 sales have been made each year. At first sales were either to the Musselshell Lumber Co. which had a mill at Musselshell Meadows or to the Potlatch Forest Inc. in lower Beaver Creek. Cut remained small until lumber prices were spurred by a war time economy. The largest cut in one year before 1946 was 18 million board feet, but the average for the 10 years prior to that had been 8.4 million.

With the increased demand for timber the Forest Service moved to open up large blocks of timber by a road construction program. A good logging road was built from Musselshell to Pierce, another from Kamiah to Lolo Creek, a third into the head of Pete King Creek then on the Nezperce Forest, and a fourth into the Sheep Mountain area.

In 1951 the Diamond Match Co. bought the privately-owned lands in the Deception-Moose Creek area and a sale was made to them for the National Forest timber there. They completed the road about 1953. From these main haul roads extensions were built under timber sale contracts by the purchaser.

|

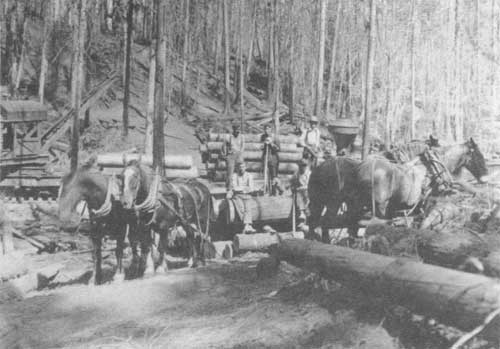

| When logging was started in the Clearwater country logs were moved by horses. |

|

| Even the railroad didn't do away with the need for real horsepower! Horses still assisted in the skidding of logs to rail loading points like this one near Headquarters in 1935. |

|

| A portion of the old Beaver Creek flume which was used to float logs down the slopes to the North Fork. It was used from 1933 to 1944 until the advent of a more extensive road system ended its usefulness. |

|

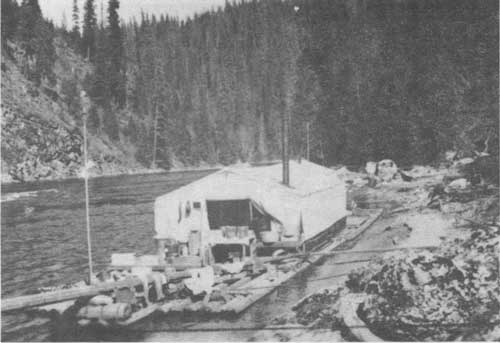

| The "wanigan," cookhouse and bunkhouse for crews on the annual log drive down the North Fork of the Clearwater. Originating from decks at Isabella Landing, the logs were floated down the river to Lewiston every year for 43 years. The last drive was in 1971. |

The annual cut climbed to 116.3 thousand board feet in 1959 and has been below 100 million only one year since that time. The average cut in the past fifteen years has been 143 million board feet. The largest cut in any one year was 206 million in 1966. They are still below the allowable annual cut of 205 million board feet, but expanding the cut goes hand in hand with extending the road system which many people oppose.

There were discussions of management plans on the Clearwater forest as far back as in the early thirties, but the timber cut was so low and fire control so uncertain that nothing was done. With the increased cut in the 1940's, cutting budgets and management plans became more practical and necessary.

The first set of timber management plans were prepared in 1950 but they were not approved. In 1953 the forest set out to prepare a new set of Management plans. Under the leadership of Robert Spencer, plans were prepared for both the North Fork and the Pierce-Lochsa Working Circles. These plans were approved in 1960 and revised in 1967.

The huge fires before the forest were established and those of 1910, 1919, 1929 and 1934 laid waste a large area. Attempts were made to plant some of the areas of double burn but finances to make more than a token showing were not available. Under the CCC program about 6500 acres were planted in the Bimerick Creek and Boundary Mountain areas. Some of these plantations were very successful but, unfortunately, in some parts of this area ponderosa pine was planted on sites where it would not do well.

Some areas around Cook Mountain and on Hemlock Creek were also planted from about 1955 to 1960 and these plantations are doing well.

In 1955 one of those freaks of nature happened that foresters dream about but seldom see. That year the forest produced a tremendous seed crop. Normally any species of tree has a good seed crop about every four years, but ordinarily the seed year of one species does not match that of another. For example, white pine may have a good seed crop in 1976 and white fir in 1977. However, in 1955 every species, for some unknown reason, had a bumper crop of seed. Even trees not over 20 feet tall were loaded with seed.

At the time this happened the Clearwater Forest had an area of about 200,000 acres that was not reproducing. A reexamination of areas needing planting was made in 1973 which showed that this had been reduced to about 50,000 acres. The forest is reducing this by planting each year. The Forest now has an enormous stand of young trees.

The cumulative cut of timber on the Clearwater Forest reached one billion feet in 1961, the two billion mark in 1969 and in 1976 went over three billion. So the Clearwater has contributed a sizable cut of timber to the nation's economy and is continuing at an average rate of 160 million feet per year for the past ten years.

There have been some large sales of timber. The largest was the Quartz Creek sale which cut out about 151 million. The Diamond Match Sale ran for 19 years, 1949 to 1968, cut 149 million. The Canyon Face sale threatens to produce more than either of these. It has a cut of 135 million and is still in operation.

A portion of the old Beaver Creek flume which was used to float logs down the slopes to the North Fork. It was used from 1933 to 1944 until the advent of a more extensive road system ended its usefulness.

The "wanigan," cookhouse and bunkhouse for crews on the annual log drive down the North Fork of the Clearwater. Originating from decks at Isabella Landing, the logs were floated down the river to Lewiston every year for 43 years. The last drive was in 1971.

The forest is endeavoring to salvage the large volumes of white pine being killed by the blister rust. Mature white pine dies rather slowly when attacked by the rust. This has given the Forest an opportunity to salvage a major portion of it. However, there are some inaccessible areas in the upper reaches of Isabella and Collins Creeks that probably will not be reached in time.

Helicopter logging came to the Clearwater in 1974. It had been developed on the coast about 10 years before coming to the Clearwater. It is past the experimental stage and holds great promise for logging steep areas which would be subject to heavy erosion by other methods.

TUSSOCK MOTH SPRAY JOB

The Bureau of Entomology, with Jim Evenden in charge at Couer d'Alene, reported in 1946 that a tussock moth infestation on the Palouse District which had been under observation for several years had reached an epidemic stage. The infestation then covered about 350,000 acres, and it was recommended that the area be sprayed with DDT in the spring of 1947 when the moth was in the larva stage.

This was one of the first and largest aerial spraying jobs the Forest Service had conducted. To spray 350,000 acres is a sizable project by any yardstick and the job was complicated by several factors. The land ownership was complicated since the National Forest, state and number of private owners were involved. The permission and cooperation of each owner had to be obtained before the project could start. Then the whole project had to be completed during the time the moth was in the larva stage, which is about a month. Another complication was that the spraying could not be done in rainy weather.

To get ready for such a large project was like planning for a battle. Everything had to be foreseen and an organization set up to take care of every detail. Headquarters were set up at Moscow with Jack Jost in charge. The newspaper clipping in the "History of the Palouse Ranger District" erroneously gives his name as "Jack Frost". Under him were a number of assistants that handled various parts of the program. Eldon Myrick was in charge of public relations. He talked to the press, answered calls from the public, and attended meetings concerned with the project. Many reporters, since they rarely if ever contacted Jack Jost, got the idea that Myrick was in charge of the project. James Evenden and his crew directed the planes, kept records of the areas covered, and tested to see that there were no misses. George Duvendack had crews transporting the DDT from the tank cars and loading the planes. The army airforce furnished the tank trucks. Norm Henry and Don Chamberlain made purchases and paid bills. Wilber Crumm and Charles Syverson of the Weather Bureau made the weather forecasts. B.F. Wilkerson established and operated a radio system that provided communication through out the area. The 14 planes were furnished by Johnson Flying Service of Missoula and Central Aircraft Company of Yakima. Landing fields were at Moscow-Pullman for the larger aircraft and at Princeton, Laird Park and Burnt Ridge for small planes.

The weather was good and the operation was completed well ahead of schedule. There were two slight accidents. One plane flipped over at Laird Park but it was not serious and the plane was soon back in action. Another plane made a forced landing, but no one was was injured.

The project was a success. The tussock moth epidemic ended and there were no complaints. No side effects were reported.

BLISTER RUST CONTROL (BRC)

I first learned that such a thing as white pine blister rust existed in early 1920 when two men came to the University of Idaho Forestry School to solicit recruits to combat it. They explained that the disease came from Europe and had been established in British Columbia and the Lake States. It was not as yet in Idaho. It was a very destructive disease and if it was not kept out could destroy the stands of Idaho white pine. They wanted to hire men to go to all the farms in North Idaho and destroy all currant and gooseberry bushes to prevent it from becoming established from such a possible source. The currants and gooseberries are the alternate host for the disease.

Early blister rust control efforts were confined to the destruction of domesticated currant and gooseberry bushes which are scientifically called ribes, and to scouting to see if there were any infested areas.

I did not go into this work, but I explained the disease and its potential to my father who introduced the first bill in the Idaho Legislature in 1923 appropriating money to combat it.

In 1923, Mrs. Ted Peterson, a school teacher, discovered and reported a blister rust infection on white pine near her husband's ranch on Browns Creek. This infection was so far from any known source at that time that her finding was doubted.

In 1925, a reconnaissance covering 3500 acres, was conducted on Orofino, Orogrande and Browns Creeks to get information on the numbers of ribes plants involved. This reconnaissance also confirmed Mrs. Peterson's report that the rust was established on Browns Creek in 1922 from an unknown source.

In 1929 the first treatment of ribes was started. It consisted of hand pulling ribes on 373 acres and spraying of 370 acres. Indications were that the disease was spreading rapidly.

In 1930 BRC started on a large scale. H.E. Swanson was in charge on the Clearwater. Working under him were Virgil Moss, Frank Walters, Jim Thaanum, B.A. Anderson, F.H. Heinrich, Lee White and others. Many of these men later became well-known in BRC and other Forest Service work.

In 1932 there were 20 BRC camps of 25 men each. About 53,000 acres were worked.

In 1933 CCC and NIRA work started. B.A. Anderson was in charge on the Clearwater. There were 4 CCC camps of 200 men each and five NIRA camps of 50 men each. In addition to their regular BRC work they were a powerful fire fighting force.

The number of men employed on BRC work continued on about the same basis as 1933 and 1942. World War II started in 1942; in 1943 BRC manpower was much reduced. In 1943 it was necessary to employ 17-year-old laborers. This continued through the war.

In 1946 2-4DT was used for the first time in spraying ribes. That year there were 12 camps employing 480 men. They worked a total of about 10,500 acres.

In 1947 employees were again 18 years or older in age. There were 435 men in 10 camps.

In 1954 the Forest Service assumed the responsibility of all BRC work on State and private as well as on National Forest lands. Up to this time the work on State and private lands was under the Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine. The BRC personnel became a part of the Forest Service. During this year the organizations were welded together as one organization under the leadership of Marvin C. Riley, who became a staffman on the Clearwater Forest.

In 1958 the Clearwater Forest experimented in the use of actidione, an antibiotic. This was first applied to trees in the Beaver Creek plantation. Test areas were also set up elsewhere in North Idaho.

Spraying trees with actidione to prevent blister rust appeared to be successful and everyone became very optimistic. Here at last, they thought, was a quick and easy method. It got away from the slow and laborious process of going over the area foot by foot and pulling the ribes. A helicopter could spray thousands of acres in one day. In 1959 the Clearwater Forest set out to spray all plantations and other areas of white pine where the disease had not advanced too far.

High hopes continued for three years when a study showed that the spray was nowhere near as effective as it was first believed to be. In 1962 a study of the white pine blister rust disease and the possibilities of growing white pine seedlings was initiated. In 1966 the results of this study were summed up in these words; "... until blister rust-resistant stock be comes available or a reliable toxicant for the rust is developed, it appears physically impossible to grow the species in reasonable quantities." This brought the BRC program to an end.

The only hope for white pine now lies in developing a rust-resistant species. This work was started in 1940. Foresters traveling through the white pine areas noticed that once in a long while they would come upon a white pine that was immune to the disease. From this came the idea of developing a rust-resistant species by crossing these trees. This idea was put into operation, but it is much more time consuming than developing a rust-resistant species for a plant that matures in one year. A white pine does not bear seed until it is from 15 to 20 years old. To get a resistant species requires crossing two resistant trees then testing and discarding the offspring that are not resistant and then crossing again and again. It requires a number of generations before a rust-resistant species is produced and a period of about 60 years before any large amount of stock is ready for planting.

The forest has planted some rust-resistant pine and the program will expand as stock becomes available. In the meantime the salvage of the mature, diseased white pine of the forest is the order of the day.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

clearwater/story/chap14.htm Last Updated: 29-Feb-2012 |