|

Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960 |

|

RECREATION AND WILDERNESS AREAS

Introduction

Pioneers in America, with few exceptions, regarded wilderness with "defiant hatred," and they battled the wilderness in the name of their nation, race, and God. Early Americans defined "progress" as the conquering of wilderness, the disappearance of wild country. By the late 19th century, in contrast, many Americans appreciated the aesthetic and recreational aspects of nature (Nash 1982:24, 40; Tweed 1980:1).

Some early outdoor clubs were established in the 1800s, such as the Sierra Club in 1873 and the Mazama Club in 1894. Even so, the possibility of forest recreation remained remote to the general population in the 1880s. At the turn of the century, the outdoor movement appealed primarily to city people. Wealthy people, intellectuals, and those with the leisure time and the money to travel were the only Americans able to visit natural wonders like Yosemite or Yellowstone or to hunt big game in the West. In general, nineteenth-century resorts developed around mineral springs, scenic curiosities, mountains, or seashores. Resort hotels were generally built for the upper class by railroad and steamship interests (Nash 1982:153; Ellison 1942:630; Jakle:53, 60).

The center of recreation in the Flathead Valley in the 1890s was Lake McDonald, which between 1897 and 1910 was administered by the GLO and then the Forest Service. Recreationists soon discovered the attractions of the South Fork, although that area required time (and usually pack animals) for a successful visit. The sport of downhill skiing had captivated some local enthusiasts by the late 1930s, and Big Mountain was developed in the 1940s on Flathead National Forest land. As the popular demand for recreation boomed after World War II, so did the recreational use of the national forests, and road construction improved access within the Forests.

General Recreation

Early outdoor recreation in the Flathead Valley focussed on resource-oriented activities such as hunting, fishing, huckleberrying, and some mountain climbing. As the transportation system improved, more remote areas became popular. For example, in 1900 a local newspaper commented that Tally Lake, which had been almost unknown until then, "is this year coming in to favor as a fishing and pleasure resort" (Flathead Monitor 11 May 1900). Some early settlers, particularly those with property on lakeshores, built tourist accommodations and thus supplemented their income seasonally. Charles Ramsey, for example, constructed a rooming house near his cabin on Whitefish Lake by 1891 to attract hunters and fishermen (this eventually also housed railroad workers, surveyors, and construction workers). In 1892 Ramsey's "fine summer resort" featured housekeeping apartments, a dining room and kitchen, and row boats (Schafer 1973:11; Inter Lake 4 March 1892).

Car camping was cheaper than using motels and restaurants, and it offered freedom of action and ways to get close to nature relatively easily. As the popularity of car camping increased after World War I, campgrounds were established to control and direct the crowds (see Figure 135). Campgrounds became more and more luxurious. In the 1920s many towns provided free municipal campgrounds, but by 1930 private campgrounds had taken over and fees were charged at city campgrounds to keep out poor people. Cabin camps, the forerunner of motels, became more and more popular and were built throughout the country (Jakle: 152, 160, 163).

|

| Figure 135. Auto camping in western Montana, ca. 1920 (courtesy of the Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula). |

Tourist camps catered to Flathead Valley residents and out-of-town visitors. Camp Tuffit and Babcock's, for example, had cabins for rent by the day, week or month on Lake Mary Ronan (see Figure 136). The camps offered meals, rowboats, and free camping (Tuffit even had rough bunks filled with hay for beds). Their patrons came from not only Missoula and Kalispell but also from various eastern states. In 1924, the Forest Service considered giving slide programs to guests at the camps (14 August 1924 memo, Flathead Inspection Reports Region One, RG 95, FRC).

|

| Figure 136. Camp Tuffit, Lake Mary Ronan (courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Region One, Missoula). |

Dude ranching in the United States expanded briefly after World War II but has declined since. The concept originated with Howard Eaton and his brothers, who began charging eastern visitors to stay at their ranch in North Dakota. Outfitter and guide Dick Randall established the industry in Montana. He began taking paying customers at his ranch near Gardiner in 1905. When the Dude Ranchers Association was formed in 1925, about 50 people attended from Montana and Wyoming. The industry boomed through the 1930s (there were 38 Montana members in 1937). In many cases, the dude business kept cattle operations from going under during the Depression (Sullivan 1971:4, 11, 13-15, 17).

Some forest homesteaders had well-established businesses guiding and outfitting and serving as dude ranches for visitors. Matt Brill and his wife started a guest ranch at their place in the North Fork in approximately 1920, taking guests on pack trips. By 1931 the Brills had created a complex there that included guest cabins, a lodge, a garage, a cookhouse, a chicken coop, a washroom/laundry facility, a barn, and so on. The site served as a guest ranch until approximately 1950. The clientele here, as at most other dude ranches, was mostly out-of-state wealthy families that returned year after year. They fished, hunted, picked berries, and relaxed (24FH105, FNF CR; L. Wilson 1988).

Other guest ranches and lodges located in the Flathead National Forest area included the Holland Lake Lodge (the original one was built in the early 1920s), a lodge built in 1927 at the foot of Lindbergh Lake, and the Diamond R Ranch at Spotted Bear (see Figure 137). The Ridenours established tourist cabins in the early 1920s on Lake Five, along the Belton Stage Road. By 1928 Flathead County had at least 16 dude ranches offering their facilities to tourists (Wolff 1980:55; Sztaray-Kountz Planning 1994:12; McKay 1993:15).

|

| Figure 137. Boaters on Holland Lake, 1936 (photo by K. D. Swan, courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Region One, Missoula). |

In 1917 well-known author Mary Roberts Rinehart and her family traveled with a large group up the east side of the North Fork, floating back down in a boat. This was a trip in the grand old style. As Rinehart herself put it, a Camas Creek homesteader watched them go by, staring "at our thirty-one horses, sixteen of them packed with things he had learned to live without." Although she wrote about being in the "wilderness," some of her party stopped at the Polebridge Mercantile and bought eggs, cheese, and a wooden pail containing 19 pounds of chocolate chips (Rinehart 1918:29, 77).

In the 1910s outfitters began taking "dudes" into the South Fork. Joe Murphy of Ovando started an outfitting business into the South Fork in approximately 1919, generally guiding wealthy hunters from the East. He built log cabins and a lodge in the area now known as Murphy Flats. There were no restrictions then; on some trips he had nearly 100 horses and mules. His permit ended in 1937 (Shaw 1967:28; Merriam 1966:23).

The very wealthy sometimes created their own private resorts at desirable locations, some of them under Forest Service special-use permits. A Denver attorney had a permit on Morrison Creek, where he built a summer home in the early 1920s. Cornelius (Con) Kelley, president and then chairman of the board of the ACM from 1918-55, and Lewis Orvis Evans (also an ACM man) were partners in an estate located on Swan Lake. Evans discovered the area while on a fishing trip and bought a small cabin there in 1908. Eventually they owned as much as 7,000 acres. Most of the building at their estate was done in the 1920s; the complex grew to include 31 buildings. Visitors were usually ACM officials and business associates from Butte and New York City. They hosted huge formal parties and often employed over 20 servants at one time (Shaw 1967:27; Pepe 1971:24-25; 24LA18, FNF CR).

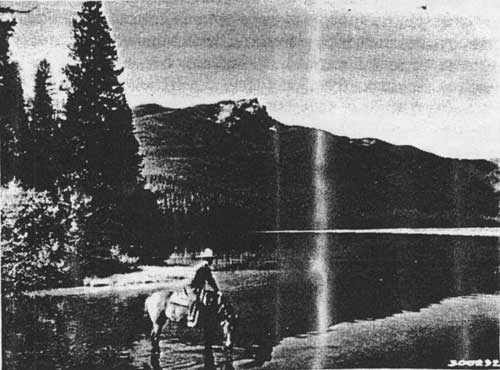

Some guided trips in the Flathead were arranged by private organizations. For example, for a number of years the Trail Riders of the Wilderness offered annual trips in the South Fork of the Flathead and the Sun River, sponsored by the American Forestry Association (see Figure 138) (R1 PR 797, 27 May 1937). Visitors on these and other trips helped publicize the Flathead National Forest.

|

| Figure 138. Trail Riders on meadow below Danaher Ranger Station, 1946 (photo by K. D. Swan, courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Region One, Missoula). |

Recreation in the Lake McDonald Area

The main area of attraction for recreational visitors within the Flathead Valley for many years was Lake McDonald (earlier called Terry Lake), located within the Flathead Forest Reserve/Blackfeet National Forest from 1897 until 1910 and since then within Glacier National Park. The lake area was well-publicized in the 1890s, although visitation was quite low at first (Buchholtz 1976a:46).

Homesteaders were filing claims to the land around Lake McDonald by 1892. The first hotel in Belton was built in 1892-93 near the railroad depot. In 1895 George Snyder built a hotel near the head of the lake, and Frank Geduhn began building summer cabins at the head of the lake. Until 1910 local residents provided most of the visitor housing, mostly cabins to rent to summer tourists or friends from the Flathead. Many of the names of natural features in the area were named after these early settlers or summer visitors, such as Snyder Ridge, Howe Ridge, and Mount Vaught. Stanton Mountain was named for Lottie Stanton, the wife of a livery stable keeper at Demersville (Ober 1973:13, 16-19; Vaught Papers 1/R).

Hunting and fishing expeditions were being guided on the east side of what is now Glacier National Park by the 1880s. The early tourists were wealthy people, including scientists such as George Bird Grinnell. In 1894 professor Lyman Sperry came to Lake McDonald looking for glaciers, encouraged by the general passenger agent of the Great Northern Railway, who saw glaciers as an attraction to rail passengers. The GNRR appropriated money to help Sperry have some horse trails built in the Lake McDonald area.

By the late 1890s Lake McDonald had places to stay, guided horse and mountain-climbing trips, and a steamer that plied the lake. The hotel proprietors there favored small-scale service and remained stubbornly independent from the railroad (Buchholtz 1976a:31, 39; Ober 1973:13).

Some of the early visitors to the Lake McDonald area climbed mountains or walked on glaciers with the help of local guides. Others had unusual adventures. For example, Frank Miles of Kalispell led a group of people in three boats on the Middle Fork. They reportedly "sometimes shot like a fish" through canyons and over rapids, fished at Lake McDonald, and eventually floated on to Demersville (Johns 1943:VII, 127).

Although publicly promoted as early as the 1880s, the designation of Glacier National Park had to wait until mining interests in the area proved a failure. The Great Northern Railway, chambers of commerce, and various outdoorsmen and scientists promoted the creation of the Park. The first bill to create the Park was introduced in 1907. The final bill of 1910 contained numerous provisions protecting special users; in reality, it was more like a modified national forest. Nevertheless, the creation of Glacier National Park fulfilled the ideals of wilderness preservation, recreational land, scientific laboratory, and nationalistic symbol (Buchholtz 1976a:47, 49).

When Lake McDonald was under GLO and then Forest Service jurisdiction, potential settlers had to obtain a permit from the government to build cabins. For example, in 1900 L. O. Vaught, an Illinois attorney, obtained permission to build a cabin on the lake for private use by himself and friends during the summer months. A Forest officer had to supervise the location and designate where the timber, stone, and other building materials were to be obtained (see Figure 139) (Vaught papers 2/F).

|

| Figure 139. Belton (West Glacier) seen from the south, ca. 1914 (R. E. Marble Collection, courtesy of Glacier National Park, West Glacier). |

In 1899 Flathead Forest Reserve ranger L. C. Hoffius wrote a series of letters to Lyman Sperry informing him of the situation in the Lake McDonald area. He built a trail that year from the foot of the lake to Hotel Glacier, worked on other trails, and patrolled for fire. He commented, "Will do all I can to keep the trails in good order for tourists. Also will endeavor to open up new country for tourists" (Vaught Papers 3/C).

The first superintendent of the Park, William Logan, planned for the new Park to be opened and used. He insured the protection of private landowners' rights, encouraged the investigation of existing mining claims to determine their validity, established a sawmill, and encouraged major construction projects. Logan and many others managing national parks at that time saw national parks as playgrounds meant for the enjoyment of the public. As Stephen Mather, head of the National Park Service, later put it, "Scenery is a hollow enjoyment if the tourist starts out after an indigestible breakfast and a fitful sleep on an impossible bed" (Buchholtz 1976a:53).

From June-October 1911, approximately 4,000 visitors entered Glacier National Park, most coming through Belton. The road from Belton to the lake was greatly improved in 1910, encouraging more tourists to visit the area. By the end of 1911 there were 199 miles of trail in fair condition in the new Park, 50 miles of which were completely new. The railroad soon built the chalet complex at Belton and planned hotels, tent camps, roads, trails, and chalets for the east side (Logan 1911:8-9; Buchholtz 1976a:56). In 1914 John Lewis' hotel on Lake McDonald (now known as the Lake McDonald Lodge) opened for visitors, and visitation to the Park gradually rose (see Figure 140).

|

| Figure 140. Glacier National Park visitation, 1911-1957 (from Bolle 1959:178ff). |

The efforts of the Forest Service and then of the National Park Service to develop Lake McDonald were slow indeed compared to those of the Great Northern, largely because of extremely low budgets. As ranger/homesteader/outfitter Frank Geduhn commented in 1912, "The Gov'ts doing here seem in comparison [with the railroad] like the efforts of a tenderfoot, I should say an imbecile" (Vaught Papers 2/E).

Flathead National Forest Recreation up to World War II

GLO regulations issued in 1902 permitted recreational use of the forest reserves in the form of building and maintaining sanitariums and hotels, camping, and travel for pleasure. In 1905, summer residences were added to the list. The 1907 Forest Service Use Book referred to national forests as "great playgrounds for the people" (Tweed: 1-2; Pinchot 1907:24). Even so, early recreation management was largely incidental to the other work of the forest rangers and guards.

Forest Service recreation policy grew out of its desire to prevent the creation of a separate parks bureau in the Department of the Interior. In 1909, according to agency figures, over 400,000 people recreated on national forests. After the National Park Service was created in 1916, the Forest Service went on the defensive (Robbins 1976:110; Kalispell Bee, 26 August 1910).

Recreational use of the national forests gave political support for Forest development and helped keep the National Park Service from being the only agency managing land for recreation. Early Forest Service recreation plans aimed at preserving scenery. In 1917, Forest Service Chief Henry S. Graves wrote that the Forest Service did not intend to protect the national forests "for a few wealthy persons who can afford to take long trips on the railroad, buy expensive pack outfits, and so on. We have a very practical problem of opening up and making available the public properties for as wide a use as possible by people of little means as well as by those better-to-do" (Graves 1917:134).

The National Park Service was created in 1916 over Forest Service protest. The next year, the Forest Service began an intensive study of its recreation facilities, commissioning a landscape architect to survey the Forests for their recreation potential. The landscape architect recommended continuing national forest recreation development separate from the national parks and hiring professional landscape architects. As soon as World War I ended the Forest Service hired its first landscape architect, Arthur Carhart, to work in the Rocky Mountain District. This was followed in 1924 by the start of the National Conference on Outdoor Recreation, which initiated recreation planning on all federal lands. In the 1920s and 1930s the Forest Service shifted to wilderness concerns, due to pressures from the public and industry and agency employees and to competition with the National Park Service for recreational budgets and land (Steen 1976:12; Tweed 1980:6-7; Baker et al. 1993:202; Roth 1984:113).

In the 1920s, the Forest Service sought to prevent the loss of large areas to the National Park Service, which was trying to preserve areas of outstanding beauty, many of them within the nation's national forests. The Forest Service moved towards a policy of wilderness preservation as a result. When Forest Service chief Ferdinand A. Silcox proclaimed in 1935 that the national forests must be managed by the principle of multiple use, he was not stating a new policy; he was presenting an argument that would prevent recreational lands from being transferred to the National Park Service. Although the Forest Service said it could manage timber and recreation together, the first purpose of the national forests was still to harvest timber. Sustained yield was the management prescription wherever there was timber, and multiple use wherever there was no timber (Swain 1963:21; Clary 1986:100-101).

Federal funding for recreation on the national forests remained very low in the 1920s. The first appropriation for Forest Service recreation was in 1923 ($10,000 earmarked for sanitation). Money was provided to build toilets, fireplaces, and so on, based on fire prevention and sanitation rather than recreational needs. In 1925 the national forests around the country had about 1,500 campgrounds, 1/3 with facilities of some sort. The Depression slowed funding even further (G. Robinson 1975:121; Tweed 1980:11-13, 15).

In the 1910s the Forest Service generally looked upon campers and picnickers with disfavor - they increased the fire hazard - but favored summer home permittees, who helped with fire control and brought in needed revenue. Beginning in 1920, the agency shifted to giving camping and picnicking priority over cottages. Designated camping and picnic areas were first established to minimize fire hazard and stream pollution rather than to serve the public (Ellison 1942:635-636).

The first Forest Service developed campground was built in 1916 on the Oregon National Forest. It offered camp tables, toilets, a check-in station, a ranger station, and a scenic trail. One of the benefits of issuing camping permits, as had been discussed even in the early 1900s, was that it provided a way to alert campers to the possibility of their starting fires by being careless with their campfires (Tweed:4; letter to District Forester, 16 February 1911, 1300 Management - Historical, Material Relating to District One Activities, RO).

The first Forest Service campground on land that is now in the Flathead National Forest was approved in 1922. The campground covered 33 acres and was located about 2 miles north of Coal Creek in the North Fork. The 1922 justification commented that more and more people were using the North Fork for recreation every year, and that the Forest Service needed to reserve tracts just for that use. In 1922, a regional official suggested a survey of the recreational possibilities and requirements in the area, noting that other sites might be desirable to reserve as well. In 1925, however, approval of that campground was cancelled because of high water in the area (FNF Lands).

From the CCC era until the building of access roads for the spruce salvage program, the main use of the North Fork was recreational. The CCC built three campgrounds there: Big Creek 1, Big Creek 2, and Tuchuck (Bolle 1959:200).

In 1932, public campgrounds were located at Fielding and Elbow (Lindbergh) Lake. The Elbow Lake camp had tables, stoves, latrines and garbage pits built that year. In 1939 the Flathead National Forest had a developed campground at Beardance on Flathead Lake that featured stoves, tables, and spring water. By the late 1930s there were also campgrounds at Hungry Horse Creek with stoves, tables, and outhouses, and at Felix Creek and Elk Park (3 August 1932 memo, Flathead Inspection Reports Region One, RO; Work Projects Administration 1939:241-42).

In 1925 the Flathead National Forest withdrew land in the Nyack area for a public campground for travellers on the highway being built through the area. Mentioned in the request was a rumor that Nyack would some day become an entrance to Glacier National Park. In 1930, a report on the Essex area commented that there were about 300 man-days of recreational use in the Marion Lake area (a good fishing lake). The report called the area "unattractive" (because of large fires in the area) but commented that the new highway was bringing an end to its seclusion (FNF Lands; 28 January 1930, "Report on Municipal Watershed," in 2510 Surveys, Watershed Analyses, 1927-29, RO).

Another 1920s campground tied to new road construction was located north of Elk Park on the east side of the South Fork. According to the Flathead National Forest, the area had "always been used by campers. New road will make it very popular. Is a beautiful spot and only one desirable along river on road for 14 miles north and 15 miles south. It is planned to set aside a Public Service site here." By 1927, the South Fork was being used more and more by tourists as a side trip from Glacier National Park (FNF Lands; 17 August 1927 memo, Flathead Inspection Reports Region One, 1920-1923 Inspection Reports, RO). Almost all of the recreationists on the Flathead National Forest arrived by car (see Figure 141).

| Type of Use | Flathead National Forest | Blackfeet National Forest |

| total number visitors | 25,000 | 9,600 |

| special-use permittees and guests | 100 | 50 |

| hotel and resort guests | 1,300 | 450 |

| campers | 2,200 | 900 |

| picnickers | 6,700 | 4,200 |

| transient tourists | 14,700 | 4,000 |

| Mode of Travel | ||

| automobile | 23,500 | 9,200 |

| railroad | 100 | 100 |

| hikers | 200 | 200 |

| Figure 141. Recreational use on Flathead and Blackfeet National Forests, 1930 (Northern Region News (10 March 1931):14). |

Beginning in 1933, funding for recreation on the national forests increased tremendously through various New Deal programs. Under the CCC, the recreation program broadened to include bathhouses, shelters, amphitheaters, and playgrounds. Recreation facilities built by the CCC for the Forest Service had to be inexpensive and simple. In 1934, each Region was authorized to hire technical personnel to oversee recreation improvements. In the late 1930s Bob Marshall, as Chief of the Division of Recreation and Lands, helped bring stronger central guidance and review, but facilities were not standardized until the late 1950s (Tweed 1980: 16-18, 20-21, 24).

According to a 1938 handbook, Forest Service managers felt that their job was to make outdoors recreation more accessible to the public with the least possible evidence of disturbance. It recommended that camps be well screened from the highway and that man-made improvements be screened by trees or shrubbery, that they be located at or near a natural attraction, make provisions for trailer use, and provide a small supply of tent poles (USDA FS, "Campground Improvement" 1935:1, 3-4, 30).

Approximately 65,000 visitors a year were using the national forests of the four northwestern Montana counties for recreation in the late 1930s. Most of the national forest visitors during the Depression lived in towns adjacent to the Forests; they had free time but little money to travel far. Campgrounds reached by roads were heavily used on weekends by townspeople and area farmers. In 1935 30% of the visitors fished, 25% enjoyed rest and relaxation, and 9% hunted. Eighty-one per cent preferred developed campsites with tables and stoves. At that time, 62% of the Region One visitors used tents, 1.3% house trailers, and 17% auto trailers. Most people expressed a desire not to have organized camps like those in the national parks (Sundborg 1945:64; Clark 1936:840-843; Wiles 1936:16).

By 1936 the national forests of Region One recognized the damage to meadows near campgrounds due to overgrazing. In the 1930s, 50 head of stock in one dude outfit was not unusual, some of them staying as long as a week in one place. Because of the damage, commercial packers and dude ranchers were required to tell rangers of their plans and routes and to limit stock use at any one feeding area to five days. By the 1930s the Flathead National Forest was collecting damages from campers who left their camps in poor condition. For instance, in 1932 the Forest Service billed a hunter for the cost of cleaning up his camp (3 August 1932 memo, Flathead Inspection Reports Region One, RO; Inspection Reports, Region One, 1937-, RG 95, FRC; R1 PR 703, 31 March 1936).

Downhill Skiing

The new sport of downhill skiing caught on in the United States in the mid-1930s, and most of the country's early ski areas were established on Forest Service land. The first winter sport area on a national forest was built in 1936 at Sun Valley, Idaho. The Forest Service generally relied on private initiative for developing ski areas (Guth 1991:181; G. Robinson 1975:126).

In the Flathead, ski parties first used Big Mountain slopes in 1935. The members of the Whitefish Hell-Roaring Ski Club built a cabin to house skiers. In 1938 members of the club persuaded J. C. Urquhart, supervisor of the Flathead National Forest, to build a two-mile road to the cabin. The Forest Service road officially opened in November 1939, with a 600' tow, and the Great Northern Railway began advertising the mountain. After World War II, veterans trained in skiing returned to the United States and skied recreationally. In 1947 Winter Sports, Inc., was incorporated and the clearing of slopes and lifts and lodge sites began. The new chalet was built in 1949, and the old cabins were burned in 1950 as fire hazards. The Big Mountain chairlift began serving summer visitors as well as winter visitors in 1951. In that first season of 1947-48, Big Mountain had 6,900 visitors. Twenty-four years later, visitation had grown to 218,400 (Shaw 1967:30; Schafer 1973:159-166; Sundborg 1945:65).

Nearly all the early ski trails and about 3/4 of the lifts at Big Mountain were located on national forest land. The runways were cleared by timber sales. The Forest Service worked together with Winter Sports, Inc., to select trail locations and to establish rules for use of the area, safety precautions, and lift charges (Montana Conservation Council 1954:54).

A small ski area was operated on national forest land just outside of Belton. It had opened by 1941. In 1959, Ed Nordtome was operating the Silver Buckle Ski course about three miles south of Kalispell with a small ski tow. A family near Creston had a commercial ski slope with a tow rope for a few years in the 1950s (Guth 1991:181; 5340 Exchange, FNF Lands file; Elwood 1994).

Flathead National Forest Recreation After World War II

When World War II began in 1941, public works recreation allotments ended, but half the Regions retained a professional recreation planner through the war period. After World War II, pent-up buying power and increased leisure time led to the flooding of United States highways with vacationers. Many resorts had been closed during the war because gas and tire rationing had limited traveling for pleasure. After the war, workers had shorter work weeks and longer vacations (Tweed 1980:26; Jakle 1985:185).

Between 1944 and 1956, recreational use of Forest Service lands in Region One increased tenfold, largely due to out-of-state vacationers. The Forest Service was largely unprepared for this enormous public demand for recreation; recreation planning and plans for the repair or expansion of facilities had been eliminated during the war. Visitation to Glacier National Park also increased dramatically, reaching half a million by 1951 (3 October 1956, 1380 Reports - Historical - Reports to the Chief, RO; Buchholtz 1976a:72; Baker et al. 1993:164, 214).

On the Flathead National Forest, recreational use climbed dramatically in the 1940s and 1950s. In 1947 the Forest recorded 40,078 recreational visitor-days. This had reached 258,000 by 1958. In 1952, for example, the Tally Lake ranger district was reporting "constant use" of the Big Mountain ski area, the Tally Lake campground, and Martin Creek Falls (Merriam 1966:77; Ibenthal 1952).

In 1949 the Forest Service was authorized to establish fee camping areas operated by private people or by the agency. Soon, larger and more luxurious accommodations appeared. Private operations generally featured motor inns instead of tourist courts (Baker et al. 1993:207; Jalde 1985:198).

The flooding of Hungry Horse Reservoir in the early 1950s replaced a high-quality trout stream with a reservoir with fluctuating levels "and dubious recreational shoreline values," according to a Flathead National Forest report. Nevertheless, the Forest Service felt that the reservoir would lead to greatly increased use of the area. At that time, annual use was approximately 7,400 (most fishermen, hunters, and campers in that order). In 1948 there were six partially developed campgrounds in the area. Forest Service officials projected needing 15-20 campgrounds to accommodate 75 family units total, plus several picnic grounds and public boat landings and swimming areas. The first summer homesites were leased in the Hungry Horse Reservoir area in 1956. By 1958, Hungry Horse had two campgrounds, Lost Johnny and Lakeview, each with four units. In 1959, there were 14 summer homesites under special-use permit on the ranger district (USDA FS "A Study" 1948:31-32; Great Falls Tribune 20 November 1955:9; Arvidson 1967; "Comparison of the Major Volume of Business," HHRD).

In the late 1950s, the Forest Service and the National Park Service began major competitive planning efforts, recognizing the greatly increasing demand for outdoor recreation. In 1957 the Forest Service established Operation Outdoors, a national program to provide recreation opportunities throughout the national forests. Each Forest developed recreation plans for the next 5 years under the program. In 1959 the Forest Service also initiated a recreation survey designed to examine the needs expected by the year 2000 (G. Robinson 1975:15, 121; Baker et al. 1993:214-215). This planning movement was similar to the National Park Service's Mission 66, a 10-year program to develop recreational facilities.

As transportation facilities improved in the area, recreational use increased. The completion of the Swan Valley Forest Highway in the late 1950s, for example, created a "boom in recreation use" in the Swan Valley (FNF "Timber Management, Swan" 1960:16).

Recreational use also increased greatly in the Coram area after the completion of the Hungry Horse dam. Between 1952 and 1960 recreation visits increased nearly 5 times in the Coram Working Circle. On other working circles it was less: from 1955-60 recreation on the Kalispell Working Circle went up 9% yearly. Recreational visits to the Glacier View Ranger District in 1958 were estimated at 56,500 (FNF "Timber Management, Coram" 1961:15; FNF "Timber Management, Kalispell" 1961:22; FNF "Timber Management, Glacier View" 1959:21).

Forest Service campgrounds were typically less developed and had fewer campsites than those in the national parks. In 1958 the Flathead National Forest had 70 campsites available, whereas Glacier National Park had the same number of campgrounds but 581 sites. In 1961, the Flathead National Forest maintained 16 developed campgrounds (the largest had 23 tables), 6 boat launching sites, and 5 commercial public service recreation resorts under special use permits (Peters 1958:95; "Areas" 1961:E5).

Creation of Primitive and Wilderness Areas

Yellowstone National Park was created in 1872, the first example in the United States of large scale wilderness preservation in the public interest. Automobiles and the building of a national highway system, the "See America First" campaign, the conservation movement, and the advertisement of national parks as the people's playground all led to increasing outdoor recreation in America. By about 1920 many people felt that the country was being criss-crossed by a network of roads; the first wilderness areas were created at this time (Nash 1982:108; Ellison 1942:632, 634).

As recreation became more and more a recognized forest product, the national forests began surveying their recreational potential. The first deliberate commitment of national forest land to wilderness was in 1919, when Trappers Lake in Colorado was protected from development. In 1924 the Forest Service designated 574,000 acres of the Gila National Forest as roadless area devoted to wilderness recreation. This was policy, not law, and few commercial activities were actually prohibited (Nash 1984:6-8).

In the 1920s the Forest Service lacked a definite policy for the undeveloped areas that it managed. The agency was unwilling to make irreversible decisions that would prevent future generations from using needed resources. In 1929 the agency defined primitive areas as places that would provide the "nature lover and student of history a representation of conditions typical of the pioneer period" (Steen 1976:156).

The 1929 "L-20 Regulations" covered national forest primitive areas. The regulations suggested limitations on unplanned development in untouched areas, but they allowed regulated use of timber, forage, or water resources. These regulations served to discourage field personnel from initiating unnecessary development and to slow the transfer of more land to the National Park Service (most national parks since 1916 had been carved out of Forest Service land) (Roth 1984:115; Merriam 1989:82).

The U Regulations supplanted the L-20 Regulations and were implemented in 1939. These regulations gave much greater protection to wilderness areas. They prohibited logging, road construction, and special-use permits for hotels, stores, resorts, summer homes, organization camps, and hunting and fishing camps. Most motorboat and aircraft use was prohibited. Livestock grazing, however, was permitted because of political pressure, as were improvements necessary for fire protection. The areas were also still subject to existing mining and leasing laws and to the possibility of reservoir and dam construction, again in response to the protests of commercial users of national forest lands. The wilderness areas created by the Forest Service such as the Bob Marshall Wilderness appealed to a new clientele, out-of-state visitors, not the usual national forest users (Roth 1984:116; Merriam 1966:113).

The rising importance placed on amenity values in the American conservation movement after World War II increased the importance of aesthetic considerations associated with quality of life. The federal wilderness bill was debated and rewritten for a number of years until its passage in 1964 (Nash 1984:8-10).

Bob Marshall Wilderness

In 1917, the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad was considering promoting the Swan and the head of the South Fork of the Flathead as a potential national park. Regional forester Silcox met with railroad officials to persuade them that recreational development under national forest regulations had distinct advantages and included such activities as pack trips, camping, and boating (10 May 1917, 1380 Reports - Historical - District 1, RO). The two areas remained under Forest Service jurisdiction.

Much of the South Fork had not been explored much by recreationists by 1920. That year, K. D. Swan and a companion traveled from Holland Lake over Gordon Pass to Big Prairie, to Big Salmon Lake (which they called "far off the main lines of travel") and out by the Monture trail to Ovando (see Figure 142). The only recreationists they saw on the trip was a honeymooning couple camping at the mouth of Salmon Creek (Swan 1921:245, 247).

|

| Figure 142. View southwest across Big Salmon Lake from the outlet, 1934 (photo by K. D. Swan, courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Missoula). |

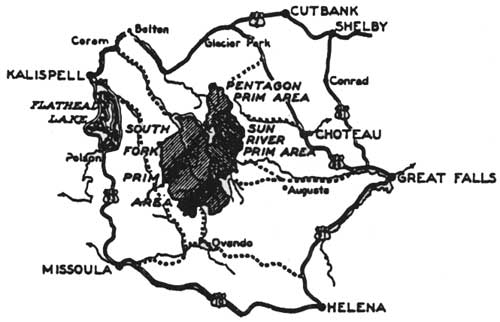

The Flathead National Forest did designate "primitive areas," however. The Forest Service established the South Fork Primitive Area in 1931 (see Figure 143). It included about 584,000 acres in the South Fork, White River, and tributaries of the Spotted Bear drainages. Citing considerable public support for the designation, the Forest Service commented that the timber in the area was commercially inaccessible for at least 30 years, that the area was not important as a water source for power or irrigation, and that there were no permanent mining claims inside the boundaries. Administrative issues included private lands within the wilderness: 69,000 acres owned by the Northern Pacific Railroad and tracts owned by two individuals. The Forest Service acquired the railroad land between 1950 and 1955 and the private tracts in 1935 and 1940. Missoula attorney Howard Toole and others outside the agency actively pushed for the land exchange through political channels in order to save the South Fork for recreational purposes (Merriam 1966:26-27; FNF Lands).

|

| Figure 143. Primitive areas on the Flathead and Lewis and Clark National Forests, 1936 (from 1936 base map, HHRD). |

Two years later, in 1933, the Forest Service designated the Pentagon Primitive Area. At first this 95,000-acre region did not include a strip along the headwaters of the Spotted Bear River because of the possibility of water power or road construction from Spotted Bear across the Divide to Bench Mark on the Sun River. In 1939 this 31,000-acre strip was added to the primitive area. The Forest Service designated the Sun River Primitive Area in 1934. The block of 240,000 acres was located east of the Divide (on the Lewis & Clark National Forest) (Merriam 1966:28).

The first designated wilderness in Region One was the Bob Marshall Wilderness, created on August 16, 1940, by combining and reclassifying the South Fork, Pentagon, and Sun River Primitive Areas. Most of the new wilderness lay within the boundaries of the Flathead National Forest, and approximately 8% of the acreage was still alienated in the southwest portion (it was owned by the NPRR). The 950,000-acre area was named to honor Bob Marshall, a forester who had passed away at the age of 38 the previous year. Originally it was planned to name the Selway-Bitterroot Primitive Area for Marshall, but Regional Forester Evan Kelley argued that Marshall's personal interest in the South Fork and its attractiveness made it the more appropriate honor. He felt that Marshall "was largely instrumental in its continuance in primitive condition" (USDA FS "Bob Marshall" 1940; Merriam 1966:32; Graetz 1985:74).

Bob Marshall was a conservationist, a forester, one of the founders of the Wilderness Society, and a Forest Service employee who devoted much of his considerable energy and talent to the development of the national forest wilderness system. He worked for the Forest Service in Idaho and Montana from 1925-28, and in 1937 he became the Chief of Recreation and Lands in the Washington Office. In 1927 or 1928 Marshall trekked through the area that later carried his name. Marshall was possibly the first high-level Forest Service official to protest discrimination in recreational policies. He argued that summer-home development, "elaborate" resorts, and high fees for ski lifts were exclusionary and should not be allowed on public lands. In the 1950s, when Communist-baiting was fashionable, the American Legion of Montana proposed renaming the Bob Marshall Wilderness for a Montana colonel who had served in World War I. The Forest Service rejected the proposal (Glover 1986:84, 253; Merriam 1989:83, 85).

As recreational and timber use in the Flathead Valley grew, frictions between the two began to be felt. One of the earliest controversies in Region One between advocates of resource use and environmentalists occurred in 1954 when the Flathead National Forest announced plans to offer for sale 23 million board feet of timber (primarily Engelmann spruce damaged by spruce bark beetle) on the upper Bunker Creek drainage just outside the Bob Marshall Wilderness. Harvesting the insect-infested timber would have required building a road parallel to the wilderness boundary for about 5 miles, plus another 30 miles to connect with the road at Spotted Bear. A local outfitter sparked opposition to the plan. The Forest Service dropped the plans for the sale, largely because an analysis showed the sale would be economical only if there were additional timber or road monies. Meanwhile, the Flathead Lake Wildlife Association petitioned for an extension of the wilderness boundary to the north and other groups for an extension to the south as well. Eventually the road was built up Bunker Creek, and the wilderness boundary was not extended in that area. But, the debate strengthened support for the 1964 Wilderness Act and the creation of additional wilderness areas in vicinity of the Bob Marshall Wilderness. The Scapegoat Wilderness was designated in 1972, the Great Bear in 1978 (Bolle 1959:8; Merriam 1989:84-85, 87; Shaw 1967:74-76).

By the time the Wilderness Act was passed in 1964, the Forest Service had already set aside 9 million acres that it managed as wilderness on its own administrative authority. Almost two million of those acres were in Montana (950,000 acres in the Bob Marshall Wilderness at that time) (Steen 1976:156; Baker et al. 1993:269). Forest Service management of the Bob Marshall Wilderness in the early 1960s was essentially pragmatic. In other words, three airfields were regularly used for supply, fire control, and emergencies, 6 lookouts were manned, and 14 administrative cabins were used within the wilderness.

Outfitter camps often "looked like tent cities"; in 1960 there was not yet a limit on the number of animals per party. The use of the Bob Marshall by commercial and private packers was still unregulated other than requiring the payment of grazing fees. Heavy over-use had developed. A Forest Service inspector recommended requiring permits for commercial packers, encouraging voluntary regulation, installing garbage pits and latrines at the main campgrounds, and developing more natural openings (Merriam 1989:85; 24PW1003, FNF CR).

Visitation to the Bob Marshall Wilderness increased about ten-fold between 1943 and 1959, going from approximately 500 to 5,000 visitors. More than 90% of the visitors continued to come on horses. The Bob Marshall was often called the "crown jewel" of the country's wilderness system (Merriam 1966:35; "Historical Look" ca. 1982:2-3; Gaffney 1941:429).

Mission Mountains

The first organized trip into the Mission Mountains was made in 1922 by a Northern Pacific Railroad and Forest Service group (see Figure 144). The railroad wanted to obtain photographs, films, and articles about the area so they could advertise it better. Forest Service employees Theodore Shoemaker and Jack Clack accompanied the group. They traveled from Holland Lake across the valley and up Glacier Creek into the high country. In 1923 and 1924 Shoemaker led groups of the Montana Mountaineers into the area. Soon he made the first map of much of the high country in the Missions. Northern Pacific officials and members of the Mountaineers named many of the lakes and mountains in the area (Theodore Shoemaker, 28 January 1955 memo, Classification of Mission Mountains Wilderness Area, RO; Shoemaker 1923:222).

|

| Figure 144. Mission Mountains, ca. 1922 (photo by K. D. Swan, courtesy of the Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula). |

In 1931 the Forest Service classified some 67,000 acres on the east slopes of the Missions as the Mission Mountains Primitive Area, adding 8,500 acres in 1939 (the high country from Piper Lake to just north of Fatty Lake). In more recent years the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes have designated the west slopes of the Missions as a tribal wilderness area. The Mission Mountain Primitive Area was changed to a Wilderness Area in 1975 (FNF "Guide" 1980; "Historical Look" ca. 1980:3).

When the primitive area was classified, the NPRR owned 30% of the land. In the late 1940s and early 1950s the railroad exchanged much of the land in the higher elevations of the area for land elsewhere in the Swan Valley. Then, in November of 1949, a windstorm blew down the trees on over 1,000 acres in the drainages intersecting the southeast boundary of the area. By 1952 spruce bark beetles had become epidemic and were spreading to adjoining stands. The Forest Service and the Northern Pacific decided to log the infested stands adjacent to the primitive area to prevent the spread of the insects. Roads were constructed into the primitive area and then were blocked once the logging of about 2,000 acres within the boundary had been completed. In 1967, the NPRR still owned approximately 2,860 acres within the wilderness, but it has since exchanged this land (FNF "Guide" 1980; Shaw 1967:80).

Jewel Basin

For many years Cliff Merritt and other Flathead Valley residents had urged that the area now known as the Jewel Basin be designated as wilderness. The public had conflicting interests in the area, ranging from trail-only recreational use to more roads for recreational use to logging of spruce in the lower basins. The Flathead National Forest arranged a trip to the area for lumbermen, ranchers, sportsmen, and others, and as a result the group recommended that the best use of the area was for wilderness-type recreation. In 1970 the Forest Service classified the Jewel Basin as a Special Roadless Area (Cooney 1964:7-8; FNF "Forest Plan":S-15).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/flathead/history/chap15.htm Last Updated: 18-Jan-2010 |