|

Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960 |

|

CIVILIAN CONSERVATION CORPS (CCC)

Introduction

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) had lasting effects both on the national forests and on the enrollees who worked in the program between 1933 and 1942. The forests obtained large numbers of workers and were able to accomplish many projects, such as road building and snag removal, that required a ready pool of labor. The men within the program gained a job and, often, skills that led to subsequent employement. The Flathead National Forest benefitted from several permanent and "spike" CCC camps located on the forest. Another New Deal-era program was the blister rust control program. Although western white pine, limber pine, and whitebark pine were killed on the Flathead by blister rust, the Flathead National Forest was not included within the official control program's boundaries.

Physical remains of the CCC camps on the Flathead National Forest are limited because the camps themselves were systematically dismantled after their period of use ended. Foundations can be seen at several sites, however. The CCC program involved building many roads, trails, recreation facilities, buildings, and so on, and some of these stand today as lasting testimony to the efforts of those young men of the 1930s.

CCC

Soon after Franklin D. Roosevelt became President, he established the Transient Service, a forerunner of the CCC program that was intended to get homeless men off the streets and out of the railroad jungles. One such camp was located on Forest Service land near the Blankenship Bridge and the junction of the North and Middle Forks of the Flathead. It opened in July 1932 and soon had about 150 men working there. They salvaged logs and sawed timber to build the camp and then worked on clearing snags from the 1929 fire. The men received $1-$3 per week wages, plus food, clothes, and shelter. The camp ran for two summers and then was shut down. In 1937 ranger Thol started construction of a mess hall and cook's quarters, using ERA labor and salvaging lumber from the old Coram "transient camp" (Green 1972:IV, 21, 23, 25; 24 November 1937 memo, Inspection Reports, Region One, 1937-, RG 95, FRC; "Coram Camp" 1933).

The act creating the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was passed by Congress on March 31, 1933. Over the next 9 years the CCC employed almost 3 million young men, local experienced men, veterans, Native Americans, and territorials in conservation work around the nation. CCC enrollees were typically between 17 and 23 years old, single, came from families on relief, and were unemployed. World War I veterans could also enroll but were housed separately. The Army ran the national forest camps, but the Forest Service developed the operating plans and work schedules. The program peaked in 1935 with more than 1/2 million men in over 2,500 camps in every state and several territories. After 1936 the number of men wanting CCC jobs dropped, and by the end of 1940 there were more positions available than men to fill them. Congress voted to end the CCC program in June of 1942 (Throop:2, 11; Salmond 1967:36, 216; Cohen 1980:18; Otis 1986:17).

CCC enrollees received a minimum of $30 a month in pay, and $22-25 of the wages were sent directly to the enrollee's family. Many of these men were away from home for the first time and working at their first steady jobs. Camp life was quite regimented. The men wore Army khaki and blue denim clothes provided from military supplies. They were allowed to leave camp on weekends, although the camps were really self-contained cities; they offered dances, cultural events, sports activities, arts and crafts, and so on. More than 25,600 men from Montana were enrolled in the CCC, and over 40,800 men served in the state. The officers from the military sometimes were frustrated with their civilian charges. One officer was overheard exclaiming to a group of enrollees at Coram, "I know you guys are not in the Army - but I wish to God you were" (Cohen 1980:25, 46-47, 151).

According to long-time Forest Service employee Elers Koch, a critic of the CCC program, it cost about $1200 a year to keep a CCC boy in camp but the work he accomplished equaled only about $300-400 in regular appropriations. He felt that the CCC, because of the low results for the money, lowered the morale and principles of regular Forest Service employees. He claimed that many foremen were "permanently ruined," and that "After these years of plenty, the organization has never gone back to its stem principles of economy and frugality" (Koch ca. 1940:169, 172).

The food provided at CCC camps was reportedly terrible (it never was as good as at logging camps, according to one participant). The Forest Service argued for months with the Army about supplying the enrollees with adequate footwear. The Army supplied regular Army leather-soled shoes, but the work required caulks (spikes in the soles) or at least hobnails to provide traction in the woods. This reduced the efficiency of the crews by 20-25% and led to some accidents (Koch ca. 1940:166-167).

During the first year of operation, the Army set up camps without standard plans. The CCC had three basic types of camp: tent camps, rigid camps, and portable camps. All had a flagpole, with an office or administration building directly behind it. A 200-man camp usually required 36 tents with board floors and wood-burning stoves. In 1937, a standard CCC camp contained four barracks, a mess hall and kitchen, forestry agents' quarters, officers' quarters, headquarters, storehouse, welfare building, dispensary, school, lavatory, bathhouse, and latrine (Otis 1986:72, 78-80).

In 1934 the CCC adopted portable camp buildings, and two years later the buildings became standardized and available pre-cut. Spike camps were limited to 20 or 25 people who were usually absent from the main camp on weekdays only. They were supervised by Forest Service rather than Army personnel and had a generally high level of production (Otis 1986:8-9, 73, 77; Cohen 1980:26). When a Forest Service CCC camp was relocated, the materials were salvaged or the buildings moved, and the Forest Service was given the first chance to obtain them.

The first CCC camp in Montana was built in 1933 for the Stillwater State Forest. At that time there were no roads on the state forest except Highway 93; CCC crews built a road from Olney to Upper Whitefish Lake and built the first state lookout (on Dog Mountain). They also felled snags left from a late-1920s fire. The state also later had a camp on the Swan River State Forest. Both state forest camps worked mainly on road construction, bridges, phone lines, horse trails, buildings, lookouts, recreational campgrounds, hazard reduction, and fire suppression. In 1939 the Stillwater State Forest got its second CCC camp, near Stryker, which was active until 1942. The men at this camp removed snags and opened roads (Cusick 1986:5-6, 9; Moon 1991:94; Sharp 1988:59).

During the years of the Depression, when logging was slow in the Flathead, many local men experienced in woods work or in carpentry were hired to serve as CCC camp foremen and logging superintendents. The Forest Service was also authorized under the Emergency Relief Act to recruit men as supervisory personnel. Many of these were graduates of forestry schools, which helped to professionalize the Forest Service. "Local experienced men" furnished their own clothing but lived with the employees. Many served as truck and tractor operators, as drillers and dynamite handlers, or directed construction work (Koch ca. 1940:169; Caywood et al. 1991:52; Sharp 1988:3).

Flathead residents, like people in other parts of the country where CCC camps were located, were not initially welcoming to the enrollees. Small-town residents were concerned about local job displacement, family safety, and other issues. Before the first New Yorkers arrived in the Flathead, the Daily Inter Lake mentioned that residents were skeptical about the "street-slum foreigners" being sent to the Flathead (11 April 1933). Generally, after the CCC camps were established the locals recognized that they helped the local economy and became much more supportive of the program (Otis 1986:2).

African-American CCC enrollees were segregated from Euroamerican enrollees as a matter of policy. Glacier National Park and the Kootenai National Forest each had at least one African-American camp, but the Flathead National Forest apparently did not (Otis 1986:7; Renk 1994).

CCC camps offered educational programs to enrollees, featuring both vocational and academic courses. For some, working in a CCC camp opened the way to a career. Carl Wetterstrom, for example, was a CCC enrollee in Washington state. He later worked as an assistant ranger, then as a CCC foreman on the Flathead National Forest, and later as a district ranger on the Forest (Salmond 1967:53; Baker et al. 1993:128).

By the end of 1940, nearly 105,000 men had served in Region One national forest CCC camps, providing approximately one million worker-days of labor. All CCC men who worked in the Flathead Valley were within the Ninth Corps area (this included eight western states), which in general sent about half the enrollees to other areas during the winter. The Missoula District included western Montana, Glacier National Park, and Yellowstone, and Fort Missoula was the training, supply, and dispersal point. When the CCC program peaked in Montana, there were 32 camps in the state (see Figure 132) (Otis 1986:17; Ober 1976:32; Caywood et al. 1991:50).

| Camp name and designation | Camp location |

| Red Meadow (F-6) | North Fork |

| Flathead (F-77) | north of Columbia Falls |

| Citadel (F-15) | Coram |

| Elk Park/Bridgehead (F-48) | Coram |

| Tally Lake (F-5) | Logan Creek |

| Olney (SF-207) | Olney |

| Goat Creek (SF-206) | Swan Lake |

| Figure 132. CCC camps on Flathead National Forest and Stillwater and Swan River State Forests, 1933-1942. Glacier National Park had 16 CCC camps during this period, including several in the Belton (West Glacier) area ("CCC Information," Intaglio Collection, UMA). |

CCC enrollees on the Flathead National Forest worked on a great variety of projects. Their jobs included removing snags left by the 1929 fires, widening and maintaining roads and building campgrounds, picnic tables, roads, fences, phone lines, bridges, and lookouts. Many of the CCC projects completed on the Flathead National Forest might not have been done otherwise for years to come (Otis 1986:19; Taylor 1981; McDonnell 1937:36). The men also served as a readily available labor pool in case of forest fires.

CCC enrollees on the Flathead National Forest, like elsewhere, were required to live up to Army expectations. After an inspection of detached crews working on trail construction and maintenance that were run by Forest Service district employees, the inspector commented:

The enrollees generally like these detachments because the forests generally feed better than the Army. They are not under as strict army rule such as standing retreat...keeping neat and clean, and making their beds, polishing their shoes etc. The camps that the detach crews maintain are not up to any army standard (CCC: Inspection: General: Flathead: Camp F-77, 19/3, RG 95, FRC).

Some Forest Service officials evidently did not maintain Army standards satisfactorily either, as evidenced by the following quote from a 1938 inspection of the Flathead Camp: "The Forestry employees are neat at the evening meal, but they should wear ties in consideration of the Army responsibility in requiring the enrollees to do so" (CCC: Inspection: General: Flathead: Camp F-77, 19/3, RG 95, FRC).

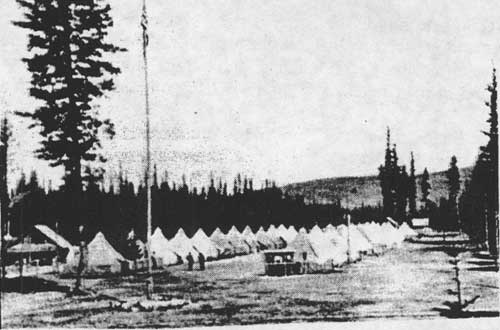

The first CCC camp on the Flathead National Forest was set up on the Desert Mountain Road in 1933 and was the only one in the Region occupied by a Montana CCC company. Ranger Tom Wiles of Coram Ranger District was the first superintendent of the "Citadel" camp. The 200-man camp worked on building a 12-mile road to Desert Mountain Lookout. Crews (often in spike camps) did trail maintenance, constructed buildings, and set up water systems, fences, and phone lines. In 1934 or 1935 the camp was moved to Elk Park on the South Fork (see Figure 133). From this camp, named Bridgehead for the pack bridge they built, enrollees constructed the first west-side road on the South Fork, the Spotted Bear landing field, and other projects. The men wintered at Nine Mile and returned to the camp several summers (Shaw 1967: 135; Sharp 1988:25-26).

|

| Figure 133. Elk Park (Bridgehead) CCC Camp (F-48), 1935 (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

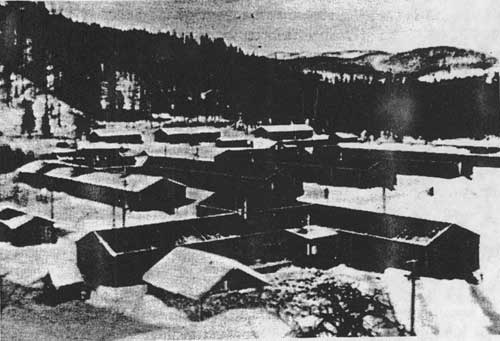

The large CCC camp northeast of Columbia Falls was built by CCC labor in the summer of 1938 on land obtained through an exchange with the Somers Lumber Company (see Figure 134). Company 952 moved into it from Elk Park in the fall of 1938. From then until it closed in April of 1942, it was the only year-round CCC work center on the Flathead National Forest. It generally had between 150 and 200 enrollees. They worked mostly in hazard reduction, felling and removing the large snags and windfalls on 127,000 acres left by the Half Moon fire of 1929. They also worked on a cooperative project with the Montana Fish and Game Department building a dam for a fish-rearing pond, and on development of the ski area on Big Mountain. In the summer, a few worked on road and phone line construction and maintenance and on other projects as needed. The camp was located so as to be in a good location to clean up the snags from the 1929 fire (the government had recently acquired about half the land burned by the fire through a land exchange with the J. Neils Company). The CCC crews felled the timber, built fire lines, and then burned the area and planted trees on it. Although New Yorkers originally lived at the camp, by the early 1940s a company from Pennsylvania had moved in (FNF, "Informational Report" 1939; 29 June 1933 memo, Flathead Inspection Reports Region One, RG 95, FRC; Sharp 1988:27; CCC: Supply: Camp Property: Buildings: Flathead, 9/6, RG 95, FRC; CCC: Plans: Camp Programs/Work Projects: Flathead, 40/4, RG 95, CCC).

|

| Figure 134. Flathead CCC camp (F-77), located north of Columbia Falls, ca. 1944) (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

In 1939, according to an inspection report, Flathead National Forest CCC enrollees worked mostly on hazard reduction and running a shingle mill operation. About 25 enrollees worked on phone maintenance in small crews. At Big Prairie men worked on the water system and the bunkhouse and maintained a fence; at Spotted Bear on the phone line and fencing; at Big Creek Ranger Station on various improvements; at Coram on farming at Tally Lake on road maintenance, and so on (29 November 1939 memo, Flathead Inspection Reports Region One, RG 95, FRC).

On the Tally Lake Ranger District, a 200-man seasonal CCC camp was located during the summers of 1933 and 1934 on a bench above Logan Creek. The men there, mostly from New York and New Jersey, built sections of the Logan Creek and Shepard Creek Roads, including several bridges. There was also a tent camp at Star Meadow that had a New York CCC company (F-5). A tent camp (F-6) was located at Red Meadow in the North Fork, also with enrollees from New York City. In 1933 Camp F-15 was a tent camp located at Coram Ranger Station (24FH64, FNF CR; Sharp 1988:5).

The men at the CCC camp at Big Creek Ranger Station built many of the improvements there in 1936, including the barn, fence, mangers, water trough and pipe line, shop/garage, dwelling and administration building, and general grounds improvement including the lawn and flagstone walks. They also worked on hazard reduction and fuelwood cutting. The "rustic architecture" of the Depression-era Forest Service buildings and structures represent a design philosophy aimed at non-intrusive expression, the use of natural and native materials, and labor-intensive building methods. The rustic style grew out of the 19th century romanticism about nature and the western frontier. Textural richness was achieved by juxtaposing materials and shapes (Throop:3, 31; Foltz 1937:25-26).

The CCC program allowed engineering in the Forest Service to take on a greater role. Because of the Depression, many engineers were available to help with CCC projects. The Forest Service developed a system for designing and building "truck trails" for fire protection, including the contour method of road staking (USDA FS "History of Engineering" 1990:5).

Some CCC enrollees on the Flathead National Forest were injured or killed while in the CCC. One Columbia Falls enrollee was killed when struck by a falling snag on a fire, and one drowned in the South Fork and another in the North Fork (Shaw 1967:98).

Glacier National Park had almost 1,300 CCC enrollees assigned to it between 1933 and 1941. In the Apgar area they worked on removing snags from the 1929 fire, graded roads, built trails, fought fires, and cleared campsites. A sawmill in Apgar produced lumber, fence posts, and phone poles (Ober 1976:30, 34-35).

When the CCC program ended in 1941, the various CCC camp buildings on the Flathead National Forest were either salvaged for rough lumber or declared surplus. Red Meadow (F-6), for example, was salvaged and the material given to the Forest Service in 1934. It consisted of a log recreation hall, a frame mess hall, a frame officers' bath and latrine, a frame latrine, and a frame shower and wash building. With the start of World War II, Camp F-77, Flathead Camp, was considered for the use of conscientious objectors or student fire crews but was rejected because of the cost of snow removal (CCC: Supply: Camp Property: Buildings: Flathead, 9/6, RG 95, FRC).

Blister Rust

The fungus known as blister rust came to America from Europe in 1909 in a shipment of nursery stock. It requires two hosts for survival: gooseberries or currants (Ribes plants), and white or sugar pine, and it almost always kills the latter. By 1923 blister rust was infecting trees in northern Idaho. The first blister rust camp was established there in 1924, and soon many more were set up to remove Ribes plants. Between 1933 and 1941 as many as 12,000 people worked on blister rust crews in the national forests (Guth 1991:32-33).

In northwestern Montana, western white pine, limber pine, and whitebark pine are affected by blister rust (Benedict 1981:23). The Flathead National Forest, however, lay on the eastern edge of the area included in the blister rust control program, so CCC and other crews on the Forest were not used to pull Ribes plants.

During World War II, emergency programs did not operate and the blister rust infection spread. Only the highest priority areas were treated. In 1948 a Forest Service study determined that the rust could be controlled, and the attempt to eradicate host Ribes plants continued. Fungicides were used beginning in 1957, but by the mid-1960s these sprayings were shown to be ineffective; control was being achieved by natural factors. In 1967, the blister rust control program in the northern Rockies officially ended (Benedict 1981:40-42).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/flathead/history/chap14.htm Last Updated: 18-Jan-2010 |