|

Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960 |

|

HUNTING, FISHING, TRAPPING, AND WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT

Introduction

The Flathead has long been renowned for its abundant wildlife; it is still a favorite area of hunters, fishermen, trappers, and admirers of wildlife. Before game laws, many early settlers killed great numbers of animals and fish for personal use or for sale. The Flathead National Forest has been involved in big-game management since the 1920s, when it began trying to regulate the population of the South Fork elk herd. The agency was also involved early on in fish plantings and in monitoring fur trapping.

Trappers have left reminders of their activities in the form of cabins and other shelters in remote drainages of the Forest. These have been affected by time and severe weather and are often almost melted into the ground. Notches cut into trees for holding a sloping log and marten bait can still be found on many of the high ridges of the Forest.

Hunting

The first significant effort to protect wildlife in the United States was aimed at game species. After 1850, legislation to protect game against uncontrolled hunting was enacted in all the states and territories. The Lacey Act of 1900 prohibited shipment across state lines of game and non-game species contrary to the laws of the state where taken, and migratory birds were given extra protection by the 1913 Weeks-McLean Law. The early years of wildlife conservation focussed largely on protection rather than active management of wildlife and their habitat (G. Robinson 1975:225-226).

Many well-born hunters and fishermen in the 1870s and 1880s supported the "code of the sportsman" and were concerned over dwindling game and habitat. Their concern helped fuel the conservation movement. The dramatic decline of passenger pigeons, of nongame birds, and of buffalo led many people to question whether the country's resources were truly inexhaustible (Reiger 1975:31-32, 50, 64).

Before the State Fish & Game Commission began regulating hunting, many people travelling through the northern Rockies hunted with great abandon. Professional hunters were hired to provide game to railroad construction crews working their way across the state. By the early 1890s hunting and fishing parties were moving to the Flathead Valley to take advantage of the area's wildlife resources. In 1890 the editor of a local newspaper commented on the industry of two Demersville residents who killed 1,500 deer in three months between the mouths of the Swan and Flathead rivers for 30 cents a skin. One upper Flathead Valley resident reported that "the early setler [sic] here in the Flathead made a regular practice of waiting until real cold winter weather set in and then killing as many deer as they thought they could use" (Vose 1964:12). (Elk was not then hunted very often because it was located in more remote areas, such as the South Fork.) (Frohlicher 1986:12; "Old-Time Flathead Tales" 1938).

Native Americans also hunted in the area until they were forcibly driven out. Forest ranger Frank Liebig reported that Cree came down every summer from Canada along the east side of the North Fork to hunt, bringing dogs trained to run down moose. They generally went as far south as Big Prairie, sometimes a little farther. The last group of Cree he saw, in 1905, reported dragging out 15 to 20 moose every year. Liebig "chased the last band out" in approximately 1905, continuing:

Settler[s] began to take up Homesteads in the Valley, and were complaining, that all the game was being killed off. So we had orders to take them [the Cree] back across the line. The[y] didn't wanted [sic] to go at first, but after we killed about 7 or 8 dogs, and the[y] saw we meant business, the[y] packed up and went back across the line, and never came back, except 2 years later 2 tepees came 4-5 miles across the line, but the[y] were there only a few days, when we heard about it, and we got them speedily back across the line again (Liebig, ca. 1940, in Vaught Papers 1/LO).

Louis Sommers recalled that the Stonies came down from Canada along the North Fork hunting in the falls of 1891, 1892, and 1893. "The latter year the ranchers organized and drove them out," he stated (Vaught papers 1/UV).

In 1895 the first Board of Fish and Game Commissioners was established in Montana. The 1895 game law limited each hunter to 8 deer per season and established seasons for various wildlife, including birds and fur-bearers. The use of dogs to chase wildlife or of dams or poison explosives to kill fish were prohibited ("The New Game Law," Inter Lake, 24 May 1895). Over time, the hunting seasons and bag limits were restricted further.

The heavily timbered forests of western Montana were traditionally relatively poor in game compared to the plains and open valleys. When David Thompson traveled through northern Idaho and western Montana between 1808 and 1812, he found game scarce (although this was partly due to the game not using the river bottoms at the time of year he traveled there). Big game populations dropped to a historic low in the 1890s and early 1900s. Numbers began to rise again due to the creation of the forest reserves, the enforcement of game laws, and later the establishment of numerous game refuges. In the days before many settlers had arrived in Montana, deer and elk were found mainly on the prairies and in the mountain valleys. In approximately 1875 they began moving into the mountains and forests, due to heavy hunting pressure, agricultural expansion, heavy logging, and fires (Koch 1941:359-360, 368-369; Carter 1951: 1).

The Whitefish Divide was at one time considered the best bear country in the state. Hunters killed many black and grizzly bear there each year (see Figure 125). The population of elk in the Flathead Valley area in the 1890s was apparently quite low. Most accounts mention seeing elk only rarely. Forest Service employee and North Fork homesteader Ralph Thayer mentioned a planting of elk in the North Fork in 1910 and said that trappers reported seeing them only rarely before that (Butler 1934:233; "Ralph Thayer" 1972).

|

| Figure 125. North Fork homesteader Mae Sullivan posing with dead grizzly bear, ca. 1930 (courtesy of Glacier National Park, West Glacier). |

GLO forest rangers acted as game wardens within the forest reserves. Lucius Hoffius, stationed at the head of Lake McDonald, in 1899 wrote to L. O. Vaught, summer resident of Lake McDonald, that locals were accusing Vaught of killing 10 deer under Hoffius' nose:

Now my policy has been not to pry into the doings of visitors too closely, and while your party may have violated the game laws, I do not believe it.

Hoffius asked Vaught for a statement denying the charge "that I may use it if necessary in closing their mouths" (Vaught Papers 2/O).

In 1900, Native Americans were still setting fires in some areas to aid in hunting. Forest ranger Benjamin Holland in the Swan Valley reported catching three different Native Americans setting fires (and he counted 64 deer and elk in their camps). As a forest ranger, he could only report the incident to the Supervisor. By 1905, however, all forest reserve employees had the authority to arrest people violating laws and regulations relating to the reserves. In 1908 Forest Service officials were asked to aid in the enforcement of state laws regarding stock, fish, game, and forest fires (31 July 1900, entry 13, box 4, RG 95, FRC; Kinney 1917:248).

The enforcement of game laws always presented a problem, and apparently some forest rangers even violated the game laws themselves. As Forest Service inspector Elers Koch commented in 1906 after visiting the Lewis & Clark Forest Reserve:

There seems little doubt that some of the rangers in the interior districts sometimes kill game out of season...It is undoubtedly a great temptation to a man to live on bacon, bread and beans for two months at a stretch with fat deer and elk practically in his door yard, and fool hens sitting beside the trail, to be had for throwing a stone, but if the rangers are to do anything toward enforcing the game laws they will have to comply with them absolutely themselves (28 November 1906, "Reports of the Section of Inspection," entry 7, box 4, RG 95, FRC).

This suspicion is confirmed by an account of a 1907 rangers' meeting along the White River. Forest Supervisor Bunker "nearly brought on a riot" when he told his men that they would be fired if caught violating the game laws. In fact, said one participant, they had venison at the meeting and would have had venison even if the game season had not been open. The rangers were used to living in the mountains and killing game when they needed it (Clack 1923a:7).

In later years, however, Flathead National Forest officials handled a number of game-law violation cases, and in almost all cases brought to trial the defendants were found guilty. For example, between 1921 and 1927 the Flathead handled 26 cases, the second highest number after the Kootenai ("Game Law" 1929:26).

Fishing

As with big game, early fishing practices were often wasteful. Many fish were caught in nets and then sold, and in 1929 the legal catch for trout was still high (40 fish per day). In 1889, for example, three Flathead residents returned to town from a fishing trip on the Middle Fork with over 600 pounds of mountain and salmon trout (Inter Lake, 1 January 1889). According to a 1900 report, all the streams in the area were "remarkably full of trout," with the most abundant about 12" long and weighing 1-2 pounds (Ayres "Lewis & Clarke" 1900:55). In 1901 Gust Moser opposed an application to establish a fish hatchery at Crystal Lake, saying that people used hatcheries as "clear subterfuge" to get around state fish and game laws, taking trout by the net to get spawn but not returning trout to the lakes (Shaw 1967:131; 20 March 1901 letter, Lewis & Clark pressbook, FNF CR).

Recreational fishing has a long tradition in Flathead National Forest waters (see Figure 126). The three principal natural species of game fish in the 1890s in the Flathead were Rocky Mountain spotted trout (cutthroat), Dolly Varden (bull trout), and native whitefish. Since then, other species have been introduced, including grayling, rainbow trout, German brown, various species of whitefish, and salmon. Kokanee salmon were introduced into Flathead Lake in 1916 (Shaw 1967: 131; Baker et al. 1993:99).

|

| Figure 126. North Fork homesteaders holding up a long string of fish, prior to 1910 (courtesy of Glacier National Park, West Glacier). |

Stocking of the streams was done by the Forest Service, the state, sportsmen 's associations, and others. For example, in 1939 Flathead National Forest officials, in cooperation with the State Fish and Game Commission, planted several hundred eggs and fingerling trout. By the terms of a cooperative agreement, Forest Service pack and saddle stock were used for planting whenever possible. The eggs' average hatch was about 75%. The area's fish population had declined because of inadequate fish ladders on the Bigfork power dam and on two Stillwater River dams; the presence of large numbers of cull fish detrimental to trout; the introduction of exotic species; unscreened irrigation ditches; silting from erosion in the agricultural areas of the valley; and inadequate fishing regulations and enforcement. The cooperating agencies planned to plant every "stream of importance" every two years and to stock as many lakes as possible by packing eggs to them (FNF, "Informational Report" 1939; R. West 1938:4-6).

By 1936 Region One of the Forest Service was doing water surveys, determining available fish food supplies, improving the streams for fish, and extending its fish stocking program. In 1938, of the 28 species of fish in the upper Flathead Valley drainage, only 10 were native. The streams and lakes were fished in direct proportion to their access by road. In 1938, the Forest Service prepared a plan to improve the fishing opportunities in the Flathead by stocking streams with the entire output of the Somers and Station Creek State Fish hatcheries (ca. 5 million fry) and to improve habitat, to construct rearing ponds, to regulate the annual catch, and to restore natural conditions (R1 PR 767, 30 November 1936; R. West 1938:2-3).

Trapping

Independent and often illiterate fur trappers leave few records, so it is difficult to know how heavily trappers were exploiting the resources of the Flathead Valley in the late 1800s. Some men stayed in the area after the fur trade era of the early to mid-1800s had ended. One fur trapper, a man named Upton, reportedly worked in the Swan Valley in 1866. A Douglas-fir tree at the site of today's Spotted Bear Ranger Station (at the confluence of the South Fork and the Spotted Bear Rivers) was found with two bullets that had been shot into it in approximately 1862, presumably by a trapper (Conrad 1964:26; Mendenhall 1925:15).

Early Flathead settler George Stannard reported on the Flathead fur trade of the late 1800s. He came to the Flathead Valley in 1888 and worked as a bookkeeper for storekeeper T. J. Demers. He reported that 30-50 other men, independent American trappers, came from the north each year to sell their furs, bringing them in on pack horses. They traded mink, marten, beaver, fisher, coyote, fox, and some bear, wolverine, and otter at Demers' store. New York fur buyers would come out and ship the furs to New York by the Northern Pacific Railroad (Vaught Papers 1/IL).

A winter's collection of furs could be large. For example, six French Canadians spent the winter of 1896-97 trapping the Big Salmon Lake area in the South Fork. They brought out 2,700 marten pelts and other furs in the spring (Shaw 1967:129).

Trappers' cabins of the late 1800s and early 1900s were typically built of logs chinked with quarter-rounds and had a dirt floor and a low ceiling. Usually the door was low, and there was only one window or none at all. The cabins were small, averaging about 10' x 12' in size. They generally were located near a source of water. According to long-time Forest Service ranger Charlie Shaw, at one time the remains of trapper's cabins could be found in nearly every drainage of the interior of the Forest (site files, FNF CR; Shaw 1967:129).

These small cabins could be far from comfortable, even in the summertime. One Forest Service worker described his despair while spending a night alone in a trapper's cabin on the Middle Fork in 1908:

as I write this I am sitting on the floor of this shack and have my book on the door sill the cabin is about twelve by nine with out any window the door is twenty inches wide and four feet high I can just stand straight up under ridgepole. I am going to hang up my shoes tonight I am afraid the rats will eat the patch off of the one they cut a hole in last night. I have killed one darned old rat allready [sic] and am looking for more with Blood in my eye good night (8/28/1908, diary in FNF CR).

Author and politician Frank Linderman described how he trapped beaver along the Swan River in the 1880s. He used "Beaver medicine" to attract the beaver to his traps. This was a mixture of castor oil, cinnamon, allspice, and cloves in equal parts, mixed with beaver oil from the glands. He used a special blaze to mark where he had set his traps. Before winter set in, he killed meat, saving the heads, necks, and offal for bait (these and other bait meat were often dragged along the traplines to attract fur-bearing animals). After trapping beaver, he would skin the hides out and then flesh them. The hides were then stretched and sewed into round willow hoops and hung up to dry. To attract martens, trappers mostly used fish entrails and heads for bait, plus anise oil (Linderman 1968:12-13; Downes 1994).

Japanese immigrant Ichinojo Sakurai trapped the Whitefish Divide after coming to the Flathead with a Great Northern construction crew. One of his cabins was an abandoned Forest Service cabin in China Basin (inappropriately named for him). He died near his cabin in the China Basin in 1918 during the Spanish influenza epidemic, and his body was cremated the next summer next to the cabin. According to at least one person, Sakurai was mapping the Whitefish Divide for Japanese intelligence. Sakurai also used a cabin now located close to the Danny On trail on Big Mountain; two other trappers trapped intermittently from that cabin until 1931 (24FH50 in FNF CR; Cusick 1986:23).

Some of the area's trappers were quite well known. For example, "Soup Creek Harry" Johnson, an early trapper and Forest Service ranger in the South Fork, was reputed to be the "Mad Trapper of Rat River" of Canadian legend, who had led the Royal Canadian Mounted Police on a long and bloody manhunt. Scotty McDougall was another trapper who achieved more than local renown. He had a cabin near Mountain Meadow on Grave Creek up the North Fork. McDougall was killed in his cabin by an avalanche in 1897. Writer Ernest Thompson Seton wrote a story about this event, and Krag Peak and Krinklehorn Peak are named for a large ram that McDougall killed and had mounted in his cabin (24FH28 in FNF CR; O. Johnson 1950:260-61).

Joe Bush, a German immigrant, trapped in the Upper Whitefish Lake area. He had two cabins along his trapline, plus a ranch on Whitefish Lake. Bush's real name was Rudolph J. Werner (Werner Peak was named for him), but he reportedly obtained his name by telling people "I am Joe and live in the bush." Bush came to the Flathead Valley after working for the Northern Pacific Railroad from 1881-83. Besides trapping, he also worked as a packer for the Forest Service, and he reportedly burned the cabins of rival trappers when he came upon them. Trapper Charles H. "Dad" Lewis also lived at the head of Whitefish Lake. Lewis had been a buffalo hunter, had participated in the Oklahoma land rush, and was a Spanish-American War veteran (24FH109 in FNF CR; Schafer 1973:7, 9).

Another trapper whose name was adopted as a place name was "Old Man Tally," the man for whom Tally Lake was named. According to various people who knew him, he was a HBC trapper who stayed in the area and "discovered" Tally Lake in 1892 while prospecting for valuable minerals. Tally lived in various camps near the lake, such as a cabin at the inlet that had only a canvas blanket for a door. He was a short man with poor eyesight. As he aged, he could not see well enough to kill game, so he used a set gun to kill deer. He came out to town twice a year to buy supplies, mainly salt and snuff. An 1896 newspaper description of Tally is as follows: "The old man is 67 years of age and notwithstanding this he plunges in to the mountain fastnesses and lives alone for months at a time. He can't walk as far as he used to but still manages by the seductive display of alluring baits to catch all the coyotes, lynx, etc., that come his way" (Vose 1952; "The Very Interesting Story of How Tally Lake Got It's Name" [sic], 1896, in TLRD).

A number of Flathead Valley trappers died violent deaths, some deliberately killing themselves in their cabins. One, a man named Slim Link, did so accidentally. He trapped in the North Fork on both sides of the international boundary and was reportedly a deserter from the Canadian Navy. In 1907 he attempted to kill a grizzly bear that had been bothering his cabin on Kishenehin Creek. Link arranged a set gun to kill the bear, but somehow he tripped it and was shot and killed by his own gun (Green 1969:I, 88; USDA FS "Early Days" 1962:209; Gregg 1991).

Trappers sometimes earned cash in the woods by unusual methods. For example, a trapper in the Tally Lake area raised a small garden of monkshood and rhubarb in a clearing by his cabin, both of which could be sold at that time on the drug market (Hutchens 1968:878-88).

A minor industry in the Flathead related to furs was the raising of fur-bearing animals on ranches. Several companies in the 1920s raised muskrats and blue foxes on natural sloughs, such as one near the Swan River that stocked 2,400 muskrats. In the mid-1920s the value of the annual muskrat catch was 1/3 that of the entire annual fur trade in the Flathead Valley (City of Kalispell 1926:44, 48).

Pelt prices for wild furs rose to high levels in the late 1920s, and then they dropped with the Depression beginning in 1929. Trapping in the Flathead Valley gradually tapered off after the 1930s. One trapper, Glenn Johnston, reported that his best year trapping was in 1915, when he caught 800 muskrats, five otter, coyotes, mink, and weasel. He felt that "trappers caught then more for the pleasure and challenge rather than strictly commercial as it is now" (in 1950) (Hash n.d.; "Glenn Johnston" 1950:3)

During the Depression of the 1930s, many Flathead residents earned cash by trapping in the winters (see Figure 127). They trapped high in the mountains for marten and weasel and in lower areas for mink and otter. In 1941 the Forest Service estimated that there were about 200 trappers operating on the national forests of Flathead, Lake, Lincoln, and Sanders counties. Fur values rose in the 1940s and have been fairly stable from the 1950s to the present (Craney 1978: Sundborg 1945:67; Hash n.d.).

|

| Figure 127. Charlie Wise and Levi Ashman with beaver, squirrel, marten, mink, coyote, and weasel pelts, Akamina Valley, British Columbia, 1934 (courtesy of Glacier National Park, West Glacier). |

Forest Service Wildlife Management

Teddy Roosevelt, responding to the slaughter of game he saw in the West, founded the Boone and Crockett Club in 1887. This organization worked to preserve big-game habitat and animals. By 1900 there was a growing sentiment for wildlife restoration. By 1905, when the Bureau of Biological Survey was established, the policy of control or repression of undesirable wildlife was being emphasized. Wildlife conservation laws and enforcement led to increasing populations of big game. Gradually heavier winter kills and damage to the forage were noted, and in some areas elk were reported to be replacing deer (T. West 1992:11; Winters 1950:139-141; Carter 1951:1).

The Forest Service's wildlife department emphasized predator control. Beginning in 1915, Congress began appropriating money for destroying wolves, coyotes, and other animals considered injurious to grazing and agriculture. The government agency responsible for wildlife, the Biological Survey, was directed more by economic pressures than by scientific research. In 1939 Congress consolidated the Bureau of Fisheries and the Biological Survey into the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Steen 1976:87; Swain 1963:44-45, 49).

Wildlife was first protected against hunting in a national park in 1894 in Yellowstone. In the early years in the national parks, the primary concern was for deer, antelope, and bighorn sheep, so they were protected by killing their predators. By 1939 this method was used only to prevent the extermination of vanishing prey species. The control methods included poison (strychnine was used in Glacier National Park), steel traps, shooting, and trailing with dogs for cougars (G. Robinson 1975:226; Cahalane 1939:229, 232-233).

The states first tried the bounty system for controlling predators. In 1914, the Biological Survey began to experiment with other control methods. By the 1930s, selected men worked as salaried hunters for the Survey (see Figure 128). In the 1930s control of porcupines was instituted because they ate the terminal buds of young trees being planted in national forests (Connery 1935:85, 98; Baker et al. 1993:96).

|

| Figure 128. Chaunce Beebe, Biological Survey trapper and hunter (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

The movement of settlers into mountain valleys of the Flathead resulted in the near extinction of the mountain lions in the area. One winter Charlie Ordish, said to be the best lion hunter in the United States, killed 97 lions on the Swan Range near Echo Lake (Flint 1957: 18).

Besides predator control, the state also tried transplanting desirable species to areas in which they had once lived or that had suitable habitat. One game transplant manager trapped about 75 mountain goats on the South Fork in approximately 1949 and then floated them downriver in a rubber boat about 9 miles to Black Bear Ranger Station. Many of these goats were relocated in the Gates of the Mountains area near Helena (Gildart 1985:101-102).

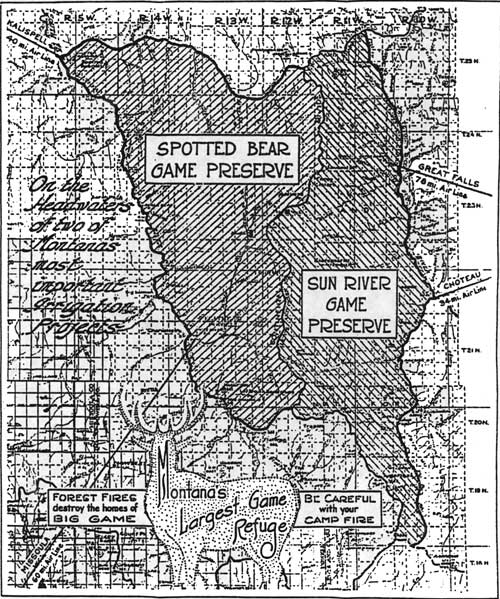

Until the World War I era, Montana depended on law enforcement to manage the game in the state, not on science. Soon after the war, game preserves were seen as the solution. Many game preserves were established on national forests to protect deer, elk, and other game. The Sun River Game Preserve, covering about 200,000 acres east of the Continental Divide, was established by the state legislature in 1912 because of concern about the elk population. This game preserve, however, did not provide critical winter range for the elk and deer. In time, game preserves proved to be less successful in game management than were bag limits and other hunting regulations (Burlingame 1957:11, 23-24; Cox 1985:230; Graetz 1985:60; Shaw 1967:72).

In 1936 the Division of Wildlife Management was established in the Forest Service. The National Wildlife Federation was founded that same year. By 1950, Forest Service policy was concerned more with game management than with preservation. Planes were first used to help in estimating wildlife populations in 1931. In 1936 Region One had 240 men carrying out a big-game study to use in a scientific approach to the management of big game, enabling them to regulate hunting on a sustained-yield basis. In 1932, the Forest Service dropped hay to starving deer for the first time (Winters 1950:144; R1 PR 675, 11 January 1936; Clepper 1971:184).

The 1937 federal Wildlife Restoration Act imposed excise taxes on guns and ammunition for the restoration of native wildlife. This had a significant effect in Montana. The funds raised were used to finance the restoration of game animals and birds (Burlingame 1957:11, 24; Rowley 1985:166).

During the Depression, big-game herds increased. Although there was more poaching during those years, the pressure of sportsmen on big game was reduced. Populations of other animals in 1967 were as follows: 250 grizzly bear, 1,200 black bear, and 450-500 moose. Some areas of the Flathead National Forest may have at one time been open grassland with buffalo herds in the summers. A buffalo horn was found beneath four feet of gravel up spotted Bear Creek while digging a root cellar at Limestone Station (Rowley 1985:166; Shaw 1967:114-116; Thol 1936:12).

The number of mule deer in the Flathead National Forest has not fluctuated as much as whitetail deer and elk populations. Whitetail deer wintered in large herds and in some years great numbers died of malnutrition. In general in Region One, deer populations rose significantly after World War II because of new state hunting regulations and predator control (Shaw 1967:113; Baker et al. 1993:90).

Deer herds on the Flathead National Forest have varied greatly in population (see Figure 129). Extensive fires on the Forest prior to 1930 created a great deal of favorable browse growth and resulted in large deer herds. Since then the transition to timber led to the starvation of large numbers of deer (for example, approximately 1,000 died in the Swan Valley during the winter of 1956-57). The Flathead National Forest began clear-cutting in small blocks to provide varied habitat to deer and help with browse growth within winter range areas (FNF "Timber Management, Swan" 1960:17-18; FNF "Timber Management, Coram" 1961:16).

| Year | Black Bear | Grizzly Bear | Deer | Elk | Moose | Mt Goat | Mt Sheep |

| 1919 | 5,385 | 1,500 | 1,100 | 515 | |||

| 1920 | 5,420 | 1,450 | 520 | 1,015 | 20 | ||

| 1921 | 640 | 235 | 5,114 | 1,200 | 480 | 1,075 | 30 |

| 1922 | 474 | 140 | 4,229 | 757 | 242 | 416 | |

| 1923 | 567 | 155 | 8,380 | 905 | 175 | 610 | |

| 1924 | 685 | 179 | 6,918 | 1,262 | 180 | 537 | |

| 1925 | 625 | 148 | 5,746 | 1,349 | 151 | 560 | |

| 1926 | 850 | 167 | 6,077 | 1,522 | 159 | 600 | |

| 1927 | 870 | 164 | 4,800 | 1,407 | 97 | 662 | |

| 1928 | 705 | 194 | 5,080 | 1,517 | 100 | 642 | |

| 1929 | 740 | 214 | 5,260 | 1.547 | 110 | 650 | |

| 1930 | 725 | 232 | 4,900 | 1,637 | 120 | 695 | |

| 1931 | 625 | 173 | 4,400 | 1,590 | 103 | 705 | |

| 1932 | 575 | 120 | 3,970 | 2,900 | 115 | 685 | |

| 1933 | 505 | 144 | 4,340 | 2,800 | 120 | 685 | |

| 1934 | 480 | 130 | 4,500 | 2,900 | 110 | 700 | |

| 1935 | 450 | 160 | 4,500 | 3,000 | 125 | 800 | 4 |

| 1936 | 478 | 160 | 4,175 | 4,266 | 145 | 835 | 4 |

| 1937 | 500 | 150 | 3,800 | 4,500 | 200 | 850 | 5 |

| 1938 | 550 | 150 | 4,200 | 4,900 | 170 | 1,200 | |

| 1939 | 600 | 160 | 4,200 | 4,500 | 200 | 1,200 | |

| 1940 | 640 | 150 | 4,800 | 4,700 | 240 | 1,250 | 15 |

| 1941 | 700 | 170 | 5,000 | 4,800 | 240 | 1,300 | 20 |

| 1942 | 760 | 170 | 5,500 | 4,800 | 260 | 1,300 | 20 |

| Figure 129. Estimates of big-game animals, Flathead National Forest, 1919-1941 (includes estimates of the portion of the Blackfeet National Forest consolidated with the Flathead in 1935) ("Cumulative Grazing Statistics" 1921, HHRD:21; "Estimates of Big Game Animals, 1942; 2270 Range Management - Records and Reports, RO). |

The South Fork of the Flathead was long used by Native Americans for hunting. They established summer camps and remained for weeks hunting elk and deer and drying the meat, which they then carried out by pack train. Unlike other parts of the Forest, the South Fork reportedly had considerable numbers of elk for many decades. The first record of elk wintering in the South Fork was the winter of 1899-1900, when forest ranger Frank Haun reported that approximately 80 head had wintered in the Big Prairie area, about 20 of them dying of starvation (Gaffney 1941:436-37; "Report on South Fork Game Studies" 1936:2).

The state legislature created the Spotted Bear Game Preserve in 1923 because of widespread fear that the new road to Spotted Bear would greatly reduce the South Fork elk herd (see Figure 131). In 1923, at the request of the Forest Service, a Biological Survey hunter was sent to hunt mountain lions in the Big Prairie Ranger District. The elk herd in the entire South Fork was then estimated at 1,200. In 1928 salting of elk in the Game Preserve began. During the 1930s there was much discussion of opening the landing fields in the South Fork to increase access for elk hunters. Bob Marshall wrote in opposition to the proposal because it would set an undesirable precedent, and the project was dropped the next day. In 1936 the Spotted Bear Game Preserve was eliminated, which helped the excess elk problem somewhat. Since 1936, hunters had been killing more elk because of the re-opening of the Spotted Bear Game Preserve, the presence of large numbers of elk, and a longer hunting season. Even so, ranger Gaffney felt the kill was still lower than the number that should have been removed (Gaffney 1941:437-438; FNF "Report on South Fork Game Studies" 1936:4; Merriam 1989:83; Merriam 1966:29).

|

| Figure 131. Sun River and Spotted Bear Game Preserves ("Montana's Largest" ca. 1923). (click on image for a PDF version) |

Factors that played a role in the increasing population of elk in the Big Prairie area included the inaccessibility of the area to hunters, the establishment of the Spotted Bear Game Preserve, the almost complete extermination of the mountain lion, and the decreasing numbers of Native Americans hunting in the area since hunting regulations were instituted. The winter range was first recognized as overbrowsed in the South Fork in 1935, and since then the damage spread from the hillsides and upper benches to the flats and stream bottoms. In 1936 the elk population in the South Fork was estimated at 4,100 but the carrying capacity of the winter range was only 2,600 (and decreasing). Predator and natural losses in the herd were about 250 per year. By 1941 the Flathead National Forest elk population had reached approximately 4,500 head, the largest in Region One, and most were concentrated in the South and Middle Fork drainages of the Flathead River (Gaffney 1941:427, 439, 451).

Beginning in 1923 Forest Service employees took annual winter trips through the elk winter range in the South Fork (see Figure 130). They counted the game in the areas they passed through and recorded the condition of the wildlife and the winter range, also checking for poaching or illegal trapping. An intensive game program began in the fall of 1933, and within a few years studies included the Swan and Middle Fork drainages. The intensive winter studies lasted four winters and determined the amount of big game wintering in the South Fork, the forage used, the influence of snow depth and temperature, the carrying capacity, game losses, migrations, and so on. These studies were followed by annual winter game patrol trips until the winter of 1941-42. After that, Montana Fish and Game put crews into the area for winter studies (Space 1936:6-7; Shaw 1967:106, 108; FNF, "Report on South Fork" 1936:1).

|

| Figure 130. Rangers Mendenhall, Thol, and Hutchinson on winter elk survey in the South Fork, having lunch at Meadow Creek, February 1927 (photo by Henry Thol, courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

For some people, winter game surveys were very serious; for others, the job had its light moments. Pat Taylor of the Flathead National Forest recalled:

With Henry [Thol], when we were snow shoeing, we were snow shoeing, while Bill [Gaffney] and I, if we were snow shoeing and jumped a coyote we'd take after it a hollering and yelling and having a lot of fun (Taylor 1981).

Pat Taylor noted that game patrol was considered a "romantic" job at that time. The public thought the rangers were making sure the game was not being poached, which was not actually their main job. Instead, they were performing such necessary tasks as dissecting all dead animals they found, washing a sample of the stomach content, cooking it in their camp stove, and identifying the contents and parasites. Taylor noted that when the Forest Service began calling the winter work game study instead of game patrol, "then the people thought all I was doing was sitting in the office writing memos or something" (Taylor 1981).

In 1952, Flathead National Forest officials commented that they foresaw no conflicts between wildlife and timber management objectives. Although construction of new roads might lead to more hunting of big game, logging on a sustained-yield basis would improve habitat for game animals and birds by creating fringe conditions. In addition, winter logging provided coniferous foliage and moss for wintering deer herds. The report also mentioned the need to control or prohibit logging along stream bottoms because it damaged the streambed conditions favorable for fish growth and propagation (Ibenthal 1952:18).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/flathead/history/chap13.htm Last Updated: 18-Jan-2010 |