|

Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960 |

|

GRAZING AND OTHER COMMODITIES

Introduction

On many national forests in the United States, grazing permits provided the largest source of revenue. The Flathead National Forest, however, had relatively few areas suitable for grazing cattle or sheep, although conditions varied as fires and timber sales changed the vegetation.

Another commodity on the Flathead that has long been popular is the summer huckleberry crop. The Flathead National Forest did not issue permits to commercial huckleberry pickers during the historic period, but the agency did attempt to monitor and manage the harvests.

The physical evidence of past grazing is found in the vegetation of grazed areas and in the occasional presence of old drift fences.

Grazing in the Flathead Valley

The first sheep were brought to western Montana, probably by Jesuit missionaries, in the late 1850s. The discovery of gold in Montana and the rise of mining camps provided an immediate market for cattle. Stockmen established themselves along the Mullan Road. The railroad construction crews and new settlements also created new markets. Cattle were trailed to Montana from Texas, Oregon, Washington, and California. The severe winter of 1886-87 eliminated many of the speculators from the northern plains cattle industry (Burlingame 1942:264, 271, 284, 286).

As rangeland to the south of the upper Flathead Valley became inadequate for the demand, cattlemen came north to Pleasant Valley and Lost Prairie from the Flathead Indian Reservation in the early 1880s. Stockmen drove their herds to winter in these areas after the fall round-ups, but there were no permanent camps there until Charles Lynch settled in the area in 1882. The Thomas Lynch ranch in Pleasant Valley grew to cover about 1,200 acres, with 1,300-1,500 cattle and 300 horses. He sold his stock to markets in Canada and later contracted with the Great Northern Railway to supply beef to their construction camps. Lynch sold the ranch in 1900 (Williams 1940:1-2).

Another cattle rancher in the Pleasant Valley was A. W. Merrifield, who had worked on Teddy Roosevelt's North Dakota ranch. He raised about 2,000 head of stock at peak. During the winter of 1889-1890 Lynch and others lost many cattle. Lost Prairie was settled later by ranchers, in the early 1900s. Two other large stockowners in the general area were Tom and Maurice Quirk, who raised cattle in the Tobacco Plains Valley beginning in 1878. Their operation grew to about 1,500 acres, with 2,000 cattle and many horses, and their markets were western mining camps in the United States and Canada (Williams 1940:1-3).

The first cattle in the lower Flathead were brought in by fur traders in 1850 to trade for horses with Native Americans in the Jocko Valley. In 1855 the Jesuits imported cattle. In the 1870s the nearest major cattle market was in Ogden, Utah, but some ranchers took their stock to Cheyenne to prime fatten the cattle and get them closer to the Chicago market (Bergman 1962:41, 43).

In the late 1880s, cattle and horses were the best cash crop the settlers in the upper Flathead could raise. The stock ran on the open range. There were four large cow outfits at that time, in the Pleasant Valley, the Smith Valley, and in the north valley. The stock lived on slough grass in the winter. Early Flathead Valley settlers had to fence to keep the range cattle out. A severe winter in 1892-1893 killed many cattle in the Flathead. Local cattlemen then realized they had to supplement natural forage during the winter with hay they raised during the summer (Vose 1964:5-6, 12; O. Johnson 1950:73-74).

General Forest Service Grazing

Before the creation of the Forest Reserves, grazing on the public range operated on a first come, first-served basis, with overgrazing common due to unrestricted numbers of cattle. Cattlemen did very well on the western ranges from the years after the Civil War until the disastrous winter of 1886-1887. Sheepmen typically owned 160 acres with water and good hay land, and in the summer they grazed in more remote ranges. By 1900, sheep were outnumbering cattle in the western mountain states (Baker et al. 1993:70; Rowley 1985:16-17).

In 1894, a federal act prohibited all driving, feeding, grazing, pasturing, or herding of livestock on the forest reserves. Public reaction against this act was strong. Western livestock interests pushed for a way to use forage in the Forests, and there was blatant violation of the act because the GLO could not enforce it (Rowley 1985:24; Winters 1950:116).

The 1897 Forest Reserve Act did not mention grazing, but an 1897 order allowed grazing on forest reserves if there was no injury to the forest. In 1899 a permit system was introduced. In 1902 the first manual on administrative procedures for the reserves allowed cattlemen to apply for grazing permits, and sheepmen could receive their allotment from a woolgrowers' association. Sheep had to be kept together in flocks, but cattle were allowed to roam at large (Rowley 1985:5, 31-32; Steen 1976:58-59, 67).

Typically one herder would be assigned to each flock of sheep, who stayed with the flock at all times. Sheepmen were assigned specific allotments (the area permitted), as were some large cattle outfits that dominated certain ranges. Many cattle allotments, however, were assigned in common, and sheep and cattle were not segregated in the early years (Roberts 1963:57, 67, 93).

The Forest Service grazing permit system gave preference first to nearby landowners, then to longtime users, then to "itinerants." Its stated purposes were to protect and use all national forest land adapted to grazing, to protect the settler and home builder against unfair competition in the use of the range, and to help the livestock industry through proper care and improvement of the grazing lands. Under the GLO, maximum numbers of stock to be grazed in each forest reserve were established. These numbers changed over the years on the national forests based on range surveys. Beginning in 1906 a small charge was made for grazing on the national forests, but the charge was less than 1/3 the actual value (Rowley 1985:54, 60; Winters 1950:119).

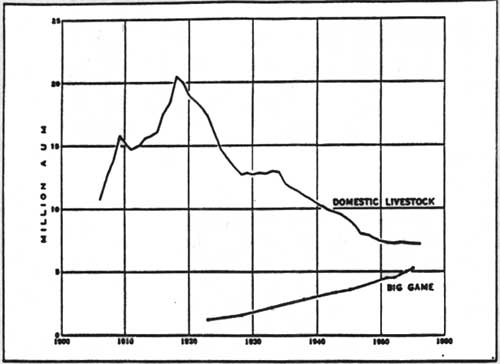

In the early years of the Forest Service, grazing use was the major activity of most western forests. Even though the grazing fees were low, they exceeded timber fees collected by the national forests until 1910 and then periodically for 10 more years (see Figure 122). Until 1917, range management on the national forests continued to improve through measures such as reductions in the numbers of livestock allowed to graze and redistributions to alleviate overgrazing (Rowley 1985:64; Roberts 1963:35, 111).

|

| Figure 122. Domestic livestock and big-game animals grazing on the national forests, 1905-1956 (Clawson & Held 1957:59). |

The entry of the United States into World War I led to higher wartime stock prices and higher allowable numbers of stock in the national forests. The demand for meat, wool, and leather rose, and many fully stocked ranges were increased by 1/3. The Forest Service was directed to make every acre of grazing lands available, and the War Finance Board extended money to banks to make loans to stockmen to increase their herds. This resulted in damaged resources and did not lead to the anticipated increase in livestock output because the feed was not sufficient to support the increased numbers of animals (Rowley 1985:95, 115; Clawson and Held 1957:58-59).

In 1919 Congress began to press for grazing permit rates to be increased to market rental value; fees on many forests were still barely half of the amount private and state owners asked. Many stock owners outside the national forests felt that those operating inside were getting a subsidy. Low fees decreased the revenue not just of the Forest Service but also of local school and road funds, which were given a percentage of Forest Service revenues. In 1924 the Forest Service completed a range appraisal and evaluation of national forest grazing fees, and the fees were increased. In 1932, however, because of the Depression, the Forest Service reduced fees by half and deferred payment until the end of the season (Rowley 1985:120, 149-150; Roberts 1963:130-132).

Stability in the livestock industry was helped some by long-term permits introduced in the mid-1920s, but the main cause of instability was the possibility of growing demands for national forest permits. In 1936 the Forest Service offered stockmen some protection from competition, including protection from arbitrary reduction of allotments and the establishment of 10-year permits. These concessions were made in response to the threat of the transfer of the Forest Service range to the Department of Interior or to a new department (Rowley 1985:129, 154-155).

Stockmen approved of predator control but saw game such as deer and elk as competing with their forage (animals that fell into neither category were ignored). During the Depression, pressures for grazing rose, but at the same time the carrying capacities were declining because of the regeneration of forests in old burn areas and an increase in wildlife populations (Rowley 1985:77, 79; Baker et al. 1993:147).

During World War II the Forest Service generally did not allow greatly increased grazing allocations as it had during World War I. Region One was an exception: during the 1930s it had continued to reduce its allotments, so in the mid-1940s the Region announced increases in permitted stock (Rowley 1985:198).

The vast public lands outside the forest reserves did not come under government supervision until the passage of the Taylor Grazing Act in 1934. That act provided for millions of acres of the public grasslands to be organized into grazing districts under the control of the Department of Interior. In 1935 the entire 166 million acres of remaining public domain was withdrawn in preparation for a nation-wide conservation program (Rowley 1985:21; R. Robbins 1976:421-422).

Drift fences were built to prevent the natural drift of unpermitted cattle and horses onto the Forest. The fences kept cattle within assigned allotments and others out and divided winter and summer range, protected winter forage, etc. By the end of 1912 the Forest Service had built 650 miles of drift fences and granted many permits for the maintenance of existing fences built in cooperation with the stockmen. The Forest Service granted free use of posts and poles and furnished wire and staples for drift fences and general-use pastures, and the stockmen bore the remaining costs. Because cattle concentrated in accessible areas and watering places, salt grounds and salt blocks were used to move them around (Roberts 1963:101, 103-104).

Grazing on the Flathead National Forest

The Flathead National Forest generally had the lowest numbers of permitted livestock grazing on its land of any national forest in Montana (the other forests with relatively low use were the Gallatin, Cabinet, and Kootenai National Forests) (see Figure 123). About 1929, a Flathead National Forest publication stated that "the demand for grazing privileges...is very light. Then, too, the density of the timber growth renders most of the land unsuited to the handling of domestic stock." On large parts of the Forest, including all of the Primitive Areas, no grazing other than pack stock was allowed, partly to protect the winter range of deer and elk. Local settlers were allowed to graze up to 10 head of animals free. Fees had to be paid on all others, including stock owned by dude ranchers ("Cumulative Grazing and Wildlife Statistics" 1954, 2200 Range Management, RO; USDA FS, "Flathead National Forest" ca. 1929; FNF, "Informational Report" 1939).

| National Forest | Cattle & Horses (#) | Cattle & Horses (AMGU) | Sheep & Goats (#) | Sheep & Goats (AMGU) |

| Absaroka | 5,174 | 18,688 | 34,742 | 64,764 |

| Beaverhead | 28,227 | 116,875 | 150,860 | 350,617 |

| Bitterroot | 2,938 | 16,703 | 8,607 | 30,607 |

| Cabinet | 1,034 | 3,950 | 7,285 | 19,890 |

| Custer | 24,014 | 157,511 | 23,668 | 48,695 |

| Deerlodge | 12,330 | 46,589 | 19,892 | 36,715 |

| Flathead | 955 | 1,542 | 4,350 | 13,050 |

| Gallatin | 4,371 | 16,998 | 26,656 | 58,323 |

| Helena | 9,021 | 37,390 | 44,737 | 79,381 |

| Kootenai | 1,712 | 8,480 | 1,300 | 5,850 |

| Lewis & Clark | 12,864 | 48,800 | 66,223 | 136,722 |

| Lolo | 1,708 | 7,929 | 10,390 | 34,210 |

| Figure 123. Livestock permitted to graze on Montana national forests, 1942 ("Cumulative Grazing Statistics, National Forests of Montana, 1919 to 1941" (1942), 2270 - Range Management - Records & Reports, RO). |

Although the land considered suitable for grazing changed over time as vegetation changed due to fires, logging, and so on, the Flathead National Forest has never been primarily suited to grazing (see Figure 124). In 1933, the Flathead National Forest listed 158,378 acres as usable grazing land, the Blackfeet National Forest 206,166 acres ("Net Usable" 1933:10).

| Year | Cattle & Horses (#) | Cattle & Horses (AMGU) | Sheep & Goats (#) | Sheep & goats (AMGU) |

| 1901 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1902 | 323 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1909 | 88 | 250 | ||

| 1910 | 61 | 250 | ||

| 1911 | 79 | |||

| 1912 | 47 | |||

| 1913 | 366 | |||

| 1914 | 82 | |||

| 1915 | 93 | |||

| 1916 | 116 | |||

| 1917 | 527 | |||

| 1918 | 901 | 18,588 | ||

| 1919 | 487 | 9,825 | ||

| 1920 | 581 | 6,650 | ||

| 1921 | 316 | 585 | ||

| 1922 | 249 | 244 | ||

| 1923 | 209 | 972 | ||

| 1924 | 163 | 1,385 | 1,292 | 3,875 |

| 1925 | 174 | 1,677 | 2,527 | 5,631 |

| 1926 | 564 | 2,162 | 3,320 | 10,253 |

| 1927 | 579 | 2,370 | 2,064 | 4,840 |

| 1928 | 324 | 1,905 | 986 | 2,582 |

| 1929 | 580 | 2,215 | 5,131 | 13,779 |

| 1930 | 1,347 | 2,272 | 5,143 | 12,954 |

| 1931 | 1,280 | 3,422 | 9,375 | 24,795 |

| 1932 | 1,413 | 3,488 | 10,933 | 28,518 |

| 1933 | 1,353 | 3,359 | 7,244 | 16,999 |

| 1934 | 1,456 | 3,536 | 14,605 | 36,636 |

| 1935 | 1,290 | 2,338 | 14,000 | 45,175 |

| 1936 | 1,431 | 2,876 | 8,900 | 20,519 |

| 1937 | 1,546 | 2,924 | 6,950 | 19,975 |

| 1938 | 1,867 | 2,108 | 4,615 | 9,238 |

| 1939 | 1,069 | 1,439 | 3,250 | 9,875 |

| 1940 | 1,423 | 2,750 | 4,650 | 13,950 |

| 1941 | 1,467 | 2,262 | 4,650 | 13,908 |

| 1942 | 955 | 6,542 | 4,350 | 13,050 |

| 1943 | 936 | 1,622 | 3,750 | 8,125 |

| 1944 | 1,415 | 2,244 | 0 | 0 |

| 1945 | 1,999 | 2,654 | 0 | 0 |

| 1946 | 1,968 | 2,577 | 0 | 0 |

| 1947 | 1,980 | 3,057 | 0 | 0 |

| 1948 | 2,430 | 3,092 | 0 | 0 |

| 1949 | 2,080 | 2,163 | 0 | 0 |

| 1950 | 1,800 | 2,614 | 0 | 0 |

| 1951 | 1,968 | 2,515 | 0 | 0 |

| 1952 | 1,985 | 2,910 | 0 | 0 |

| 1953 | 2,011 | 3,096 | 0 | 0 |

| 1954 | 1,990 | 3,084 | 0 | 0 |

| 1955 | 2,122 | 2,426 | 0 | 0 |

| 1956 | 1,220 | 2,742 | 0 | 0 |

| Figure 124. Livestock permitted to graze on the Flathead National Forest, 1901-1956 (includes statistics for the portion of the Blackfeet National Forest consolidated with the Flathead in 1935) (Bolle 1959:254; "Cumulative Grazing Statistics, National Forests of Montana, 1919 to 1941" (1942), 2270 - Range Management - Records & Reports, RO; Rowley 1985:51; Shaw 1967:128). |

One of the areas favored for grazing in the Flathead was the Swan Valley, where grazing was closely tied to homesteading. In the late 1880s a stockman from the Flathead wintered his cattle at the head of Swan Lake, and another at the head of the Swan River. The Flathead National Forest later designated this area (after logging by Somers Lumber Company) and adjacent timbered slopes as a sheep allotment, but in 1922 there was no local demand. Local settlers grazed cattle and horses in the Swan Valley in a strip 6-10 miles wide in the valley, only using about 25% of the carrying capacity of the land. The alienated land in the valley complicated grazing administration, so that permits were issued based on the proportion of grazing done on government lands. In 1930, the stock grazing in the Swan River watershed was 221 cattle and horses. The estimated capacity would provide for 800 cattle and horses for a 5-1/2 month season. A report commented that "Withdrawal of the grazing privilege would probably result in about a 50% evacuation of the valley by its present inhabitants and deter any further settlement" (Johns 1943:111, 82; 11 September 1922 memo, Flathead 1920-23 Inspection Reports, RG 95, FRC; "Report on Big Fork Watershed," 28 January 1930, in 2510 Surveys, Watershed Analyses - Analyses of Municipal Watersheds, RO).

Sheep allotments in the Flathead National Forest included areas of the Whitefish Range, the Swan Range east of Swan Lake (including Quintonkon Creek on the South Fork), Bruce Mountain, the Mission Range, the Echo-Coram area, the area between the Middle Fork and Bear Creek, and a few others. Sheep use peaked in 1917 with a total of 18,000 head, and in 1939 it was down to 8,830 head of sheep (Shaw 1967:128; FNF "Informational Report" 1939; 15 September 1927, 2230 - Permits - Historical, RO).

Permits for grazing sheep on the Flathead were never in high demand, largely because of windfalls and the absence of desirable plants. In 1934 a Forest Service inspector commented that local residents were "very bitter against the sheep on account of the fact that the winter deer range is depleted by the sheep, although they do not report any unusual losses in deer from starvation." The ranger in the Swan and the forest supervisor recommended no sheep permits in the Swan, although at that time there were allotments on the Swan/South Fork divide (Baker et al. 1993:71; 8 March 1934 memo, Flathead Inspection Reports Region One, RG 95, FRC).

One of the allotments in the North Fork was on Shorty Creek below Nasukoin in the 1930s. Paths of snow slides there provided good forage. The head of Red Meadow Creek also supported one band of sheep. In the Tally Lake area in the 1930s, Island Meadows issued a small grazing permit, and cattle grazed Star Meadow beginning in 1935. Several bands of sheep were driven over what is now the Big Mountain Ski Area to summer range in the early 1930s (Yenne 1983:52; 19 September 1930 memo, Flathead Inspection Reports Region One, RG 95, FRC; 24FH41, FNF CR).

In 1952, a Flathead National Forest report recommended grazing cattle in ponderosa pine woods to trample the soil and encourage ponderosa reproduction. Until then grazing in the Tally Lake area had been confined to small herds of locally owned cattle using natural meadows during a short summer period (Ibenthal 1952).

The Flathead National Forest has traditionally received much use by pack animals, and the Forest Service regulated their grazing. For example, in 1941 about 200 horse-months of forage were required on the Big Prairie Ranger District for the use of visitors' stock, and another 200 for government stock. By 1958 Big Prairie was supporting an average of about 500 animal months of grazing of commercial pack stock (and private stock was about equal in use) (Gaffney 1941:429; 24PW1003, FNF CR).

After World War I ended in 1920, many stockmen in Montana, especially cattlemen, faced a sudden and sharp decline in livestock prices and went bankrupt. During the early 1920s prices climbed, but then the drought and the Depression beginning in 1929 led to forced liquidations of both cattle and sheep herds. By 1927 Montana had organized state grazing districts that combined private, state, and federal lands into a grazing commons, with grazing rights allocated to district members. The 1940s were good years for stock in Montana, and the range recovered. During World War II beef cattle were raised at record levels, but the production of sheep declined due to a shortage of experienced labor and high cattle prices (Winters 1950:120; Burlingame 1957:I, 329-330).

The grazing allotments on the Flathead National Forest have changed over the years as conditions and market demand have changed. For example, an allotment in the Nyack area along the Middle Fork and a small area north of Essex were not grazed under permit until 1959, when 24 animal months were permitted. Grazing was prohibited when the South Fork Primitive Area was created, and commercial grazing was also not allowed in the Mission Mountains Primitive Area because of the lack of forage and the rough terrain. Generally the grazing allotments were not overstocked (grazing files, HHRD; 24LC923, FNF CR; Wright 1966:54).

The charges for grazing permits were generally quite low on the Flathead National Forest, as on other Forests. In 1927, Supervisor Hornby recommended that rates for grazing on the Flathead range from 1 to 10 cents per head per month for sheep (it varied depending on the quality of the range and difficulty of access). He recommended that the commercial packers' rates for horses be 12-1/2 cents per horse month, a reduction from 14 cents (15 September 1927, in 2230 - Permits - Historical, RO).

Other Commodities

One of the early-recognized commodities of the Flathead National Forest was the summer huckleberry crop. Many early settlers of the Flathead Valley traditionally picnicked or camped in the mountains during huckleberry season, picking large quantities and then canning them for home use or selling them for income (Flathead County Superintendent 1956:25).

Forest Service employees were involved in huckleberry management early on. For example, in the 1930s the lookout on Desert Mountain spent considerable time with huckleberry pickers in that area to aid in fire prevention and to distribute them so as to better use the crop (his wife manned the lookout while he was on other jobs) (18 December 1938 memo, Inspection Reports, Region One, 1937-, RG 95, FRC).

During the Depression, picking huckleberries provided needed cash for many Flathead Valley residents, and Forest Service campgrounds such as the one near Echo Ranger Station filled with berry pickers. In 1932, the Flathead National Forest (not including the Blackfeet) estimated that 20,000 gallons of huckleberries were picked on the Forest. At that time there was a debate over whether or not huckleberries in some areas of the Forest might be a more profitable use of the land than timber. By the early 1930s labor-saving devices for commercial huckleberry picking had been developed, such as a beater that gathered 50 gallons a day versus 5 by hand or 12-15 by scooper, and a new cleaner that used wire-bottom troughs, replacing the blanket (Swan River Homemakers Club 1993:339; Hammatt 1933:6-7).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/flathead/history/chap12.htm Last Updated: 18-Jan-2010 |