|

Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960 |

|

FOREST HOMESTEADS

Introduction

One of the principal reasons for opposition to the creation of forest reserves was the inclusion of agricultural lands within forest boundaries (Kerlee 1962:6). The "closing of the frontier," announced in 1892, led settlers to look for unoccupied land in areas such as deserts, cancelled railroad grants, Indian reservations, state and school grants, reclamation projects, and agricultural lands inside the national forests. The Forest Homestead Act of 1906 was passed in order to make this agricultural land available for settlement.

The original Homestead Act of 1862 allowed a settler 160 western acres free if he or she lived on it for at least five years, cultivated a certain number of acres, paid a small filing fee, and built improvements on it. The law allowed the settler to commute his entry and purchase the land at $1.25 an acre (in 1891 Congress changed the minimum period before commutation from 6 to 14 months) (Dunham 1970:6, 155).

Land for homesteads had to be surveyed first by the General Land Office (GLO). Once the land had officially been surveyed, "squaters" had the first right to file a claim on the land they occupied. The Flathead guide meridian was run by the GLO in 1892. Almost all squatters filed a declaration of occupancy, and in the summer of 1893 a complete survey was made. The settlers then could file on the claims if they had located before March 3, 1891, when the pre-emption law was repealed. Most proved up in the fall of 1893 for $1.25 an acre, with an additional cost of about $50.00 (Robbin 1985:19: Schafer 1973:10).

The Forest Homestead Act of 1906 allowed U. S. citizens to file for homesteads within national forest borders. This law resulted in some settlement in the Flathead and Blackfeet National Forests, but many of the homesteads eventually reverted back to the Forest Service. Administering the provisions of the act took much of the forest ranger's time in the early 1900s.

Forest homesteads are represented on the ground by homesteaders' cabins, barns, outhouses, etc., some in good condition and still in use by private owners (mostly for recreation) and others standing only a few logs high.

Forest Homestead Act of 1906

The Forest Homestead Act of June 11, 1906, allowed people to settle on land primarily suited for agriculture located within the national forests. The act was intended to quiet the protests of those unhappy with the inclusion of non-forest lands within the forest reserves and also to attract "a superior type of homesteader" to the Forest who would help protect its resources. Many settlers within the Forests had not yet filed homestead claims because the areas had not been surveyed by the GLO, so they had no way to secure title. They received preference in establishing a claim, if they had not located on land containing valuable timber or mineral resources. The government was required to survey and list for settlement all agricultural lands within the national forests. Once surveyed and approved, these "June 11th claims" could be homesteaded. The claimant had to pay a per-acre filing fee, occupy the claim for several years, cultivate the land, construct a house and outbuildings, and within five years file the required proof of residence and cultivation. As with non-forest homesteads, settlers could sell their land once they had "proved up" on their claim (Hudson et al. ca. 1981:216-217; Gates 1968:512; Kerlee 1962:115, 158).

This act significantly lessened the opposition to the forest reserves. As a 1910 Daily Inter Lake editorial commented, the "almost universal opinion" about forest reserves in the Flathead in 1897 was that they would retard the development of the country. The inclusion of good agricultural and fruit land was especially objectionable, but since then the Forest Service was "constantly becoming more liberal in its dealings with prospective settlers." Local people felt land should be classified according to its soil, not the standing timber, and believed that "a family engaged in raising foodstuffs contributes more to the general good, than would come from the tract of timber in its natural state." The opposition to the forest reserves themselves, the article continued, "has largely disappeared" (Daily Inter Lake 1910:3).

Until 1905, the owners of patented land inside forest reserves could exchange their land for land outside the reserves. The chief beneficiaries of this lieu-land provision were the railroads and the states, however, not individual homesteaders as had been intended (Peffer 1951:47).

The Three-Year Homestead Act was passed in 1912 to encourage claimants to complete their residency requirements on forest homesteads rather than commuting their claim and moving off. The act reduced the residency requirements; claimants could obtain patent if they lived on their claim at least 7 months a year and met the minimum cultivation requirements (Hudson et al. ca. 1981:218; Dana 1980:22).

Beginning in 1912, in an effort to systematize the approach to evaluating potential forest homesteads, the Forest Service was required to open all lands classified as agricultural to settlement. This resulted in the opening of many small tracts that otherwise would have been retained by the Forests. These later homesteads were generally smaller (the national average was 70 acres), of poorer quality, and more isolated than the earlier ones. One example of this was an 11.58-acre homestead on Swan Lake that today would be a summer home site (Kerlee 1962:75-77).

The Forest Service soon realized that it needed to make its own withdrawals in order to keep suitable sites available for administrative and other needs. Rangers recommended and surveyed these withdrawals (which on many national forests covered more than were ever used). By 1912, the Forest Service had established one ranger station for each 60,000 acres of Forest. The government also withdrew sites for recreation areas, sawmills, log banking, water power sites, rights of way, etc. (Kerlee 1962:52, 56).

Some Forest Service officers were occasionally overzealous in rejecting homestead applications. If rejected, the claimant had to pay for a hearing. Much land judged agricultural by would-be settlers was rejected as such by the Forest Service; the rangers were trying to ensure "prosperous homes." Another reason the Forest Service may have been slow in granting homestead claims was that no extra funds were appropriated to administer the Act. Much potential homestead land had not yet been officially surveyed and classified (Cameron 1928:282; Peffer 1951:65; FNF Class; Kerlee 1962:51, 54).

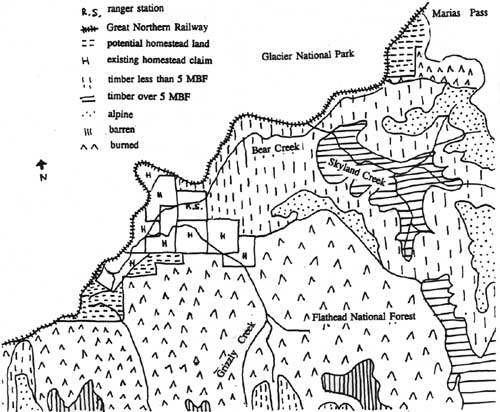

By 1917 the Flathead and Blackfeet National Forests had conducted extensive land classifications to define the areas that were chiefly valuable for agriculture. The potentially agricultural lands were then intensively classified, and appropriate lands were listed for opening to settlement. On the Flathead National Forest, most of the agricultural land was confined to stream terraces and gently sloping glacier upland. Some land initially rejected was later reexamined and listed, but many requests were turned down. Rangers frequently denied such requests on the Flathead and Blackfeet National Forests because the applicant had selected land that the Forest Service considered chiefly valuable for timber, although it was not yet marketable due to access problems. Rather than defer action on a request for years, while waiting for the timber to be harvested, the Forest decided to reject such requests (see Figure 115) (M. H. Wolff 1925:67, 99; FNF Class).

|

| Figure 115. Map era homestead in the upper Swan Valley applied for by Rudie Kaser, showing irregular boundaries following a streambed. In this case, the applicant requested the larger outline but the Forest Service rejected the majority of the land because it had timber estimated at 2-5 MBF per acre and thus was not primarily valuable for agriculture. The 32.5 acres were opened to settlement in 1922 (FNF Class). |

Applicants accompanied examiners whenever possible. The report on a proposed homestead addressed markets, transportation, topography, soil cover, and economic possibilities. The homestead boundaries were typically quite irregular in shape because the survey lines followed the contour of the mountains and took in natural clearings, springs, and creeks and avoided timber as much as possible. Most were surveyed by metes and bounds based on a common corner. By the end of 1924, approximately 465,000 acres in Montana and northern Idaho national forests had been listed for settlement (Kerlee 1962:77-78; M. H. Wolff 1925:110).

The isolation of forest homesteads was a barrier to social and economic activity. Many homesteaders raised cattle and horses that could be driven to market in good weather. Many if not most men worked in the logging industry, for the Great Northern Railway or for the Forest Service (or the National Park Service in the Middle and North Forks). Working for the Forest Service was considered partial fulfillment of the residency requirements even though the person might be absent, and the employment was at a busy time of year for a farmer. Homesteaders were required to report trespass of any kind on the reserves (grazing, timber cutting, and so on). Typical crops raised included hay, oats, and other grains for stock feed, plus vegetables for home use, fruit, and berries (Kerlee 1962:80-83). Typical outbuildings on a forest homestead included a log barn, an outhouse, a chicken house, sheds, and corrals.

From 1906 until 1912, approximately 60% of forest homestead applications were disallowed or voluntarily withdrawn. Government officials never believed that much of the land in the Flathead and Blackfeet National Forests was truly agricultural (see Figure 116). The first inspector sent through the newly created Lewis and Clarke Forest Reserve in 1899 stated clearly that the reserve had no "strictly agricultural land" except for some in the Birch Creek area (on the east side of the Divide). He continued, "In each of the main valleys some vegetables and hay could be grown, but the product could not compete successfully with that produced under more favorable conditions." He mentioned several favorable locations for small ranches but noted that they were isolated (Kerlee 1962:55; Ayres "Lewis & Clarke" 1900:3940).

The Forest Service could protest the issuance of a patent if the amount of land cultivated did not meet the requirements. Many homesteaders filed for a reduction of these requirements, and some were granted. In 1917 Frank Fisher of the North Fork applied for a reduction, stating:

I have worked with a desperation the last three years to accomplish these results but with little progress more than to open up the claim and establish a place to live. I have built a road of 3-1/2 or 4 miles cutting it through the thick timber... [but] without means and [with] the necessity of earning my living as I go along as well as improve my claim, my progress must of necessity be slow and unless I can get relief will surely fail in meeting the requirements of the law though I may exhaust my life in my efforts (FNF Adj)

The Blackfeet National Forest rejected Fisher's request, saying that he had "not been very diligent in clearing and cultivating the land." In 1918 the GLO overturned this decision, both because Fisher had built a long road and because he was so poor (FNF Adj).

The Forest Service rejected another claim because the applicant, Thomas Arneson, did not meet the residency requirement; the family lived in Missoula 9 months of the year so their children could attend school there. The case was heard before the register of the U. S. Land Office in Kalispell, and in 1923 the applicant was issued final proof (FNF Adj).

In 1912 Henry Graves defended the Forest Service policy on homesteads in a Saturday Evening Post article. In explaining the reasons for refusing to open for entry all lands requested by claimants, he talked about the Swan Valley as a case in point:

The Swan River Valley contains upward of 30,000 acres of amble lands bearing a virgin forest of yellow pine of 15,000 to 40,000 board feet to the acre. Its value under present conditions is $2.50 a thousand, averaging $50 per acre. The timber on an average claim would be worth $80,000 (quoted in Kerlee 1962:68).

In 1913, the Regional Office reported that "the general sentiment around the Flathead Forest is not as a whole very favorable. There has been a general feeling that there has been considerably too much delay on the part of the Forest Service in opening up agricultural lands in the Swan River Valley estimated to be approximately 34,000 acres, and the South Fork of the Flathead, estimated to be approximately 82,000 acres, to entry" ("Public Sentiment in District 1," 18 November 1913, 1380 Reports - Historical, RO:26). (The delay in the Swan was due to waiting for the GLO survey of the area to be completed.)

On the Blackfeet National Forest in 1913, opposition to the Forest Service focussed on the issue of agricultural land that was to be opened to entry as soon as the timber was removed. Some timber owners who were "genuine speculators trying to pose as persecuted homesteaders," according to a Forest Service report, wanted the Forest Service to keep its stumpage prices high Historical, RO:19).

Some homesteaders took their appeals of Forest Service decisions directly to politicians. James Wiltse Walker, for example, a successful Kalispell businessman, supported a proposed bill reducing the requirements for proving up on a forest homestead. He appealed to Secretary Lane, who had defeated this bill, and Lane sent a personal representative to visit Walker's homestead. The representative was reportedly "amazed" at the amount of clearing that had to be done and told Walker he had done enough work for his patent (FNF Class).

Some cases brought out a great deal of personal information. Ora Rainwater of Spokane filed for proof of claim on a homestead on the Flathead National Forest and was rejected. The forest ranger reported that he had heard Rainwater was married and said, "I have seen several strange women going to and coming from his place. It got to be so notorious one time that I dubbed the place 'The Happy Hollow Harem.'" Nevertheless, Rainwater was issued patent on his claim just a mile southeast of Belton in 1922 (FNF Adj).

The greatest abandonment of patented and unpatented homesteads on the national level happened between 1912 and 1930. Many lands that were filed on were too small to succeed as farms or ranches. In the Blackfeet National Forest, 198 homesteads had been listed and entered on by 1930. In 1930, 121 (60.6%) of these were abandoned or not in use. According to the rangers in the area, the reasons were as follows:

5 too far from market 50 greater economic advantages elsewhere 58 poor soil 5 sold to adjoining ranches 2 disappearance of local markets 1 old age

On the Flathead National Forest, only 148 of 267 claims were still in the hands of the original claimants or their heirs in 1930. In 1930, 94 of the 267 claims were unoccupied or not being farmed. Of the 119 on the Forest that were not under their original ownership, rangers gave the following explanations:

48 sold after patented 6 muskrat farmers 7 bought for hotels, resorts, or summer homes 4 cancelled after entry, found to be on NPRR land, settler refused re-entry 3 reverted to county for taxes 5 leased to tenant farmers but not by original patentee 1 occupied by logger 4 owned by bank or loan company 26 entered, abandoned, succeeding entrymen 2 occupied by laborers 1 reverted, rented by Forest for fox farm (Kerlee 1962:92-93)

As described above, many of the forest homesteads filed on in the Flathead Valley were submarginal, and the residents sooner or later drifted away (see Figure 117). In the 1930s, following the drought in eastern Montana and the Dakotas, many of the old homesteads "were again occupied by people who were delighted to see something green." Between 1929 and 1941, about 500 farm families moved into the Flathead Valley from east of the mountains. In a program that lasted from the 1930s until 1952, many homesteads and tax-delinquent properties were consolidated into the national forests. Other homesteads were again abandoned during World War II. The Flathead National Forest estimated that by 1962, 50% of its homesteads had been returned to the Forest (see Figure 118) (FNF "Timber Management, Kalispell" 1960:48; Kerlee 1962:94-95; Skeels 1941:4-5).

|

| Figure 117. Homestead of Ralph and Esther Day in the North Fork. Among the challenges faced by homesteaders in the Flathead National Forest were long, severe winters (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

| Year | Alienated Land (Acres) | Total Flathead National Forest Land (Acres) | Percent of Total that is Alienated |

| 1924 | 484,723 | 3,043,171 | 15.9% |

| 1939 | 394,997 | 2,600,000 | 15.1% |

| 1985 | 278,740 | 2,628,674 | 10.67% |

| Figure 118. Chart showing the declining percentage of alienated land within the boundaries of the Flathead National Forest (the alienated land represents homesteads, railroad land grants, State land, etc.). The 1924 figure includes the Blackfeet National Forest (USDA FS "National Forest Areas" 1962; FNF "Informational Report" 1939; FNF "Forest Plan" 1985:III-38). |

The classification of the lands in the Forest was difficult; sometimes it was even difficult to find the claim based on the applicant's description. Local rangers tended to give adverse reports on the classification of particular tracts, only to have their decision reversed by the regional officials. But the large number of abandoned homesteads may show that many of these lands really were unsuited for agriculture, and that many homesteads were taken up as speculation. Regional officers were more lenient in granting homesteads than local officers, perhaps because they wanted to foster good public relations, because they believed the local officers were not competent in their decisions, or because they found it politically expedient to release the tracts (Kerlee 1962:103-04).

In the 1930s the Forest Service ordered rangers to burn abandoned cabins and outbuildings on the homesteads that had reverted to the Forests in order to restore the Forests to their natural settings (Kerlee 1962:83). In fact, many of the homestead lands now have greater value for recreation than for agriculture or timber.

Stillwater Area Homesteads

Early settlements in the Stillwater area concentrated along the Fort Steele-Kalispell road (also known as the Tobacco Plains Road or Trail). Along this road within the forest reserve in 1899, forest inspector Ayres found five occupied houses, four with gardens and fields. David Stryker had about 80 acres under cultivation. Some of these ranchers supplemented their farm income by boarding travelers (Ayres "Flathead" 1900:254).

A 1924 Forest Service inspection report claimed that the homesteads along Good Creek were "an economic blunder" that should never have been listed for agricultural use. The inspector continued, "Grazing cattle, venison, moonshine, and possible summer work with the Forest Service or on the County road constitute the only evident immediate resources of Good Creek. There is little doubt that the settlers have made some use of all of these resources, although there are but few cattle in the locality." At least one Good Creek homesteader found a creative way to make a living; he did the laundry for the logging camps in the area. As if to verify the above comment about moonshining as a source of income, long-time Stillwater State Forest employee Maurice Cusick commented, "When the bootlegging days were on, that Olney was a regular depot!" (7 February 1924, Flathead 1920-23 Inspection Reports, RG 95, FRC: Cusick 1986:31: Cusick 1981).

Some homesteaders were colorful characters who claimed to have exciting pasts. According to one account, the Gergen brothers, who homesteaded up Good Creek, appeared to fear for their lives. They wore guns strapped to their waists and walked 20-30' apart. By another account, however, the Gergens were simply farmers from North Dakota who wintered in Olney and ran cattle on their homestead in the summers, returning to their home in North Dakota in the 1930s ("Tally Lake RD List of Names," TLRD; Cusick 1986:31).

Other homesteaders lived in self-imposed exile. Two bachelors who lived separately on Qettiker Creek, Albert Jones and Charles Oettiker, were each university graduates and "meticulous housekeepers." Jones had reportedly been released from a government job for gambling, and Oettiker had left Austria to escape military service. Both trapped for the money they needed and lived on their garden produce, game, and fish (Hutchens 1968:65-66).

Some homesteaders were well-to-do professionals who either wanted a second home or simply liked living in the woods. An example of this is provided by Alba Tobie and Frances Jurgens Kleinschmidt, who had adjacent claims in the Tally Lake area and soon were married. Tobie was an assistant cashier at Conrad National Bank in Kalispell, and after he and Kleinschmidt were married in 1910, he visited the claim every Saturday night while she lived there continuously. In 1912, according to a Blackfeet National Forest employee, their furnishings were those "found only in a modern home" and included carpets, bedding, fixtures, porcelain bath tub, wood shed, tools, gasoline engine, a "patent wood saw," and 200 jars of fruit and jellies. There was also a spring house, fences, and a one-acre garden. The Tobies "are people who would rather live in the country than in town, not because of any financial difficulties, but because they like the claim" (FNF Adj).

Claim jumpers appeared in the Flathead Valley as elsewhere. One documented case was on a Stillwater River homestead claim of Kalispell businessman McClellan Wininger. He found several men building a house on his homestead. Following a fight that resulted in gun and ax wounds, the defendant (Wininger) was acquitted (Johns 1943:IX, 23).

Schools were established in the more remote valleys to serve the children of forest homesteaders. For example, a school was built at Tally Lake in 1910. A school at Patrick Creek in the early 1920s had 10-12 students (Kalispell Bee, 11 October 1910:3; Cusick 1981).

North Fork Homesteads

After the initial coal mining boom in the early 1890s, settlement in the North Fork was abandoned for a time. Some of the miners cleared homesteads on the Home Ranch Bottoms to raise cattle, but the poor range and severe winters drove them out of the North Fork. One who did live in the North Fork in the late 1890s was Aaron Long, who worked as a packer in 1901 for geologist Bailey Willis. Willis said Long had lived five years on Logging Lake, that he had a dugout canoe made from a cottonwood log, and was "almost the last of the race of woodsmen, trappers, and hunters, whose occupation is nearly gone in this region" (FNF "Timber Management, Glacier View" 1949:40; Willis 1938).

In 1899 H. B. Ayres noted about 30 unoccupied cabins in the North Fork Valley, many in "tumble-down condition," plus two occupied cabins at Bowman Creek and at the Coal Banks. He felt that the North Fork could support agriculture, but only if there were a road and if the reserve were protected from fire, for it "would furnish good locations for forest rangers who by some farming on such lands could occupy their time when not employed on the reserve" (Ayres "Flathead" 1900:253-254, 284).

Homesteaders in the North Fork were attracted by the timber, wildlife, hopes of coal, oil, and railroad development, and natural meadows. The first permanent settlement was in Sullivan Meadow on the east side of the river, about a day's trip north of Belton by wagon. Early settlement concentrated on the east side of the river because the road was located there (at that time, both sides of the river were part of the Blackfeet National Forest). By 1910, only 14 homestead claims had been filed on the west side, whereas 44 had been filed on the east side. Following the designation of Glacier National Park in May of 1910, however, the concentration of settlement abruptly shifted to the west side of the river, and about 100 more homestead claims were taken up on that side in following years (Bick 1986:1, 3-4).

In 1908 Charlie Wise, Chaunce Beebe, and Fletcher Stein established the first three homesteads on the west side of the North Fork. According to Eva Beebe, wife of Chaunce, "They homesteaded because it was a hunter's and trapper's paradise. And they felt they were in heaven there. No rangers...nobody to bother them, you know. They made their own laws. That's what they wanted" (Beebe 1975).

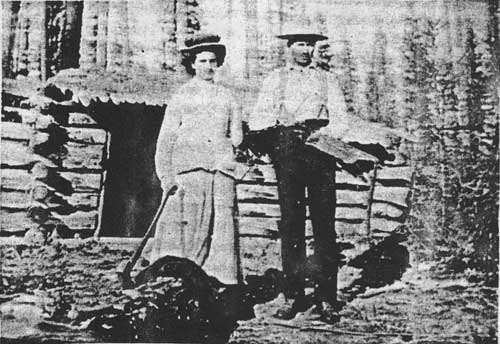

Construction on the west side road began in 1912, and in 1914 Bill Adair moved his business out of Sullivan Meadow on the east side of the river, where he had built a store in 1904 and opened a hotel in 1907, to the west side of the river near Hay Creek. The store is now known as the Polebridge Mercantile (see Figure 119). Adair built a log house in 1912 on his homestead claim near Hay Creek (this is currently the Northern Lights Saloon next to the Polebridge Mercantile). Improvements by May 1917 included a house, log barn, log chicken house, and the mercantile, plus a well and fence and 20 acres of crops (Bick 1986:14; FNF Adj).

|

| Figure 119. Bill and Emma Adair standing in front of their cabin next to the Polebridge Mercantile, ca. 1940 (the cabin is now the Northern Lights Saloon) (courtesy of Glacier National Park, West Glacier). |

A 1917 Forest Service examination of the homesteads on the upper west side of the North Fork concluded that the land was best suited to forage crops in conjunction with livestock raising because of the severity of the climate. Most of the homesteaders by then were devoting most of their time to outside work and had only a few acres prepared for cultivation (Lewis 1917:14-15).

By 1910 there were 30 year-round residences on the upper west side of the North Fork. More than 40 properties were proved up and became private inholdings within Glacier National Park after it was created in 1910. By 1922, more than 150 homesteads were located in the valley, and there were twice as many families as single men. In 1920 homesteader Ben Hensen opened a store, gas station, and new post office near Adair's store. He gave the post office the name Polebridge after a nearby bridge, and the community in that area has been called Polebridge since (Burnell 1980:2; Bick 1986:1; Walter 1985:11; "New Store" 1920:1).

Besides the bridge near the mercantiles, settlers built two "flying dutchmen," or hand-pulled cable cars, to cross the North Fork, and there was a bridge just north of the Canadian border until the flood of 1964. Other amenities included a phone system; most of the settlers were connected to one of the single-strand phone lines put in by the Forest Service or the National Park Service. A weekly stage served the North Fork, plus several post offices (three at one time in 1922). Settlers could send in their orders on credit to Adair's store via the mailman (and after 1920 to Hensen's store also). Adair made a weekly trip to Kalispell, and then the mailman delivered the orders to the customers. Homesteaders could order anything from "horsedrawn hay rakes to upholstery tacks to baby shoes to English teas." Prohibition (1918-34) did not stop all from indulging in alcohol; during this period some settlers regularly ordered 100-pound sacks of sugar (Hamor 1975:9; Walter 1985:12, 14-15).

Blackfeet National Forest officials seemed to interpret the forest homestead regulations rather liberally at times. In 1906 Edward R. Gay of Kalispell applied for land in the Camas Creek Valley. He owned the Kalispell Malting & Brewing Company, and the Forest Service employee reporting on the application noted that "as he is a brewer by trade and profession and has a very comfortable home in Kalispell - a more comfortable one than he can make of the tract - it would seem that speculation was his reason for applying." Nevertheless, Gay was offered 115 acres on which to file (the other 45 were considered chiefly valuable for timber) (FNF Class).

The growing season in the North Fork was 70-75 days. Homesteaders generally built a root cellar and raised a garden; because of the long winters, root vegetables were an important part of the diet. Most had a dairy cow and a few chickens, plus some horses. As was true elsewhere, hay was the main cash crop, which homesteaders sold to government agencies, tourists, or neighboring ranchers. There was no machinery for harvesting wheat until the 1920s, when a thresher was brought in. Many grazed stock at Home Ranch Bottoms south of Polebridge, but venison remained the primary source of meat. A higher percentage of married couples chose home sites with scenic views than did bachelors (Bick 1986:18, 31-34, 36; Walter 1985: 13).

The early North Fork homestead residences, outhouses, hay sheds, barns, root cellars, and even fences were all built of logs with some purchased items such as doors and windows. The earliest log residences were generally one- or two-room cabins with steeply pitched gable roofs covered with cedar shakes. As they had more time and money, many built new residences that were larger, 1-1/2 or 2 stories, with bigger windows and more milled lumber. The outhouses often had dovetail corner notching, more difficult to construct, which allowed them to be relocated as needed. The barns were generally used for horses in the winter; most of the cattle was sold in the fall or wintered elsewhere (Bick 1986:50, 53-56).

The off-the-farm occupations of North Fork homesteaders varied greatly. Many worked for the Forest Service or Glacier National Park for years, usually doing seasonal work such as trail location and construction, packing, or serving as fire lookouts (see Figure 120). Some helped build the Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park in the 1920s. Some lived on military pensions, worked for the CCC in the 1930s, ran traplines in the winter, worked on the construction of the west side road, constructed log buildings for other settlers, worked in the summer tourist trade at Lake McDonald, or were employed at the oil fields in Canada. Others spent the winters in town. For example, Orville Cody worked in a bakery and George Steppler as a barber in Kalispell. Raising rabbits and knitting angora socks was tried, as was raising elk and training them for racing at fairs (the latter project ended abruptly when the state legislature passed a law prohibiting the fencing in of wild animals) (Bick 1986:36; Walter 1985:12; 24FH470, FNF CR; Vaught ca. 1943:394).

|

| Figure 120. Theodore Christensen and Anna Neitzling (later his wife). Theo Christensen worked for the Forest Service in the early years (courtesy of Glacier National Park, West Glacier). |

Some of the North Fork homesteaders, according to historian Jerry DeSanto, were "silent residents who were often very colorful, often very handy on the trail and in the mountains, and very reticent about their past." One of these was "Uncle Jeff" (Thomas Jefferson), who lived at Sullivan Meadow until 1915. He had been a gold miner in California, a Pony Express rider, and a scout for General Nelson A. Miles. Once in the North Fork, he made money by selling his coal claim, and he worked as a guide for scientists and tourists. His home served as the welcome stopover place for non-paying guests traveling up the North Fork (DeSanto 1982:16-19).

Andy Vance was another of these intriguing settlers. He had hunted buffalo, sold elk meat in Livingston, been a guide for big-game hunters through the Rockies from Colorado to Canada, and participated in the Klondike gold rush before coming to the North Fork. Others found homesteading in the North Fork too tame and even too crowded to remain; Paul Abbot left his homestead on Trail Creek to seek more solitude in Alaska. Another notable North Forker was Jack Reuter, an early squatter on the east side of the river. He had worked on Teddy Roosevelt's ranch in North Dakota and was reportedly the Wannigan of Roosevelt stories (USDA FS "History of Engineering" 1990:48; Hamor 1975:16; Vaught Papers 1/UV).

The North Fork is a good example of the power of word-of-mouth in attracting settlers to an area. Many of the homesteaders were related; one member of a family would settle and then others would visit and later file on a homestead claim themselves. Some experienced family tragedy while living in this remote area. For example, Charlie Wise's daughter died after swallowing a button, and then his wife passed away during the 1918 Spanish influenza epidemic (Bick 1986:17; "Ralph Thayer" 1972).

Providing an education for one's children presented a challenge in the North Fork. There were several schools in the valley over the years; the locations changed somewhat as the concentration of settlers shifted. The schools included a tent on Indian (Akokala) Creek and facilities at various times on Big Prairie, Red Meadow, Trail Creek, and just north of Polebridge (see Figure 121). Some children rode horses to school, crossed the river in a rowboat, or boarded with neighbors or at the Adair store (Hamor 1975:4-6).

|

| Figure 121. School near Polebridge, ca. 1921 (courtesy of Glacier National Park, West Glacier). |

In 1911 and 1912, soon after the creation of Glacier National Park, residents of the east side of the North Fork signed a petition asking that it be excluded from the Park. They asserted that it contained at least 50,000 acres of agricultural land and that the rest was valuable timber land "with no particular scenic value." In 1915 they again appealed, claiming that "it is more important to furnish homes to a land-hungry people than to lock the land up as a rich man's playground which no one will use." They claimed that the area had not been and never would be visited by tourists. The homesteader's petition was not granted, and after 1954 there were no year-round residents on the east side of the river (Kauffman 1954:4, 7; Bick 1986:49).

[text missing in printed edition] cultivated land, "not even a garden." He did note three or four trappers' cabins and the home of Daniel Dooty, one of the forest rangers for the new forest reserve (Ayres "Flathead" 1900:253, 316).

Relations among homesteaders were sometimes strained. According to Middle Fork homesteader Louise Giefer, she was induced to come west by Philip Giefer to file on a homestead; he promised to make his own home on a mining claim. In several lengthy letters to the Forest Service, she stated her case for obtaining the title to the homestead, located near Fielding at the mouth of Bear Creek. She said that she had done all the work on it since settling there in 1906. In July 1912, she reported, her husband "shot at me and put me in fear of my life." She had been unable to live on the land because he had refused to leave. As the Forest Supervisor commented, "the domestic relations of the Giefer family are decidedly complicated." In the summer of 1915, 39 people sent a petition to the U. S. Land Office requesting an investigation of Philip Giefer who, they claimed, was a "habitual trouble-maker" and was responsible for at least six homesteaders deserting their land (FNF Class).

The hopes of the neighboring homesteaders and of Louise Giefer were apparently not realized, however, for in 1923 Philip Giefer was still living on the homestead he had first claimed in 1900. He was doing relatively well, too, for at that time he had a two-story log cabin, a barn, a tool shed, four small outhouses, two miles of fencing, 51.25 acres under cultivation (40 acres of which were irrigated), 22 sheep, two work horses, and harvesting machinery and agricultural tools (FNF Class).

Some homesteaders in the Middle Fork (and possibly other areas as well) turned their anti German sentiment during World War I on their neighbors, and the Forest Service had to mediate their disputes and evaluate the "patriotism" of certain homesteaders as a result. Immediately after the United States entered World War I in the spring of 1917, the regional forester wrote all forest supervisors asking them to report alien sympathizers to law enforcement officers and to list points that might need protection (bridges, tunnels, and so on) (Baker et al. 1993:113).

The National Espionage Act was being used to suppress sedition at this time. In February 1918 a bill intended to suppress free speech became law in Montana, making it a crime to utter, print, or write any disloyal language about the government, Constitution, or U. S. Armies. A person could be fined or jailed for showing disrespect or contempt toward the military, the flag, or the government. The federal Sedition Act, closely modeled on the Montana act, was passed in 1918 and repealed in 1921. According to historian K. Ross Toole, "Montana raised the level of general hysteria higher than any other state." Anyone with a foreign accent or German ancestry was suspect (Toole 1972:139-40; Gutfeld 1979:39, 43).

For example, Nick Badanjak's request for a homestead in the Middle Fork was rejected because the land was more valuable for timber. He protested this ruling, but then neighbors wrote the Forest Service accusing Badanjak of being disloyal. In 1918 assistant district forester F. A. Fenn asked the forest supervisor for more information on why Badanjak did not buy liberty bonds from Mrs. Kruse, the wife of the ranger at Nyack. Badanjak had reportedly told her that he did not have the money and would not "give one cent to help this Government, it's just a bunch of crooks," and that he planned to return to Austria when the war was over. In 1918 the Department of Justice investigated the case, concluding after the war ended that he was indeed disloyal, but that the land could be listed for homesteading without a preferred applicant (FNF Class).

Nyack homesteader Harry F. Davis caused a great deal of trouble for the Forest Service between 1911 and 1914. According to a thick file, Davis wanted to file a homestead claim on land that had been withdrawn for the Deer Lick Ranger Station. He eventually was given some of the land so he could have access to water and a building site. Davis took his case to prominent Flathead Valley citizens and to a lawyer named Thomas. Some light is shed on his motives, perhaps, by a letter from the Kootenai National Forest supervisor, written in 1912 and included in the Davis file:

Mr. Thomas is a shyster lawyer who has made it a point for several years to stir up a feeling of discontent against the Forest Service and especially to encourage litigation between the Government and homesteaders. He makes it his especial business to solicit cases of this kind usually making the prospective client any kind of a wild promise in order to get his small retaining fee. He has been a continual thorn in the flesh to the administrative officers of this Forest as well as to those of the Flathead and Blackfeet (FNF Class)

Harry Davis was also involved in trying to prevent a neighbor, John Edward Warner, from obtaining final proof on his claim in Nyack. Davis wrote the Forest Service claiming that Warner was a fugitive from Colorado and that "his conduct during the war was of a very unAmerican type...He is somewhat of a leader of a community of unAmerican Swedes and is a very undesirable class of citizen." The office of the solicitor decided that there was no basis for these allegations, and Warner obtained the patent (FNF Class).

Other homesteaders took the time to write the Forest Service appreciative letters, such as Essex homesteader Thomas E. Dickey. In 1914 he wrote, "I am very thankful to you for the kindly interest you have taken in assisting me to secure a title to my Homestead here. I have received only the most uniform kindness from all connected with Forestry Department in all the years I have been here, and I am thankful to all" (FNF Class).

South Fork Homesteads

Thomas Danaher and A. McCrea established 160-acre homesteads in the upper basin of the South Fork (Danaher Meadows) in 1897 or 1898. They seeded 60 acres to timothy hay for their 160 or so head of cattle and 20 head of horses. They also harvested about 70 tons a year of wild hay. The distance to market and low crop yields led McCrea to abandon his land and Danaher to sell out to the Missoula Hunt Club in 1907. The latter attempted to raise horses on the land, but that endeavor also failed. In 1913 four claims in the Danaher Basin were filed, but none were ever occupied. As with much of the South Fork, long winters and distance to market over a rough trail made farming and stock raising uneconomical (Merriam 1966:20; 2 March 1901 letter, 1901 Lewis & Clarke pressbook, FNF CR; Shaw 1967:5, 74; FNF, "Extensive" 1914:6-7).

Another well-known homesteader of the South Fork was Mickey Wagner (real name Skubinznck), who was living on his land at the start of the trail up the South Fork near Coram by 1910. Like other homesteaders, he earned cash and met his residency requirements by working seasonally for the Forest Service. He worked as a cook at Big Prairie, and he helped locate and build many trails in the Coram area (Opalka 1983; "S. Fork" 1967).

Swan Valley Homesteads

Homesteading in the Swan Valley was relatively late; most claims there were established between 1916 and 1920. One reason for the delay was that the Forest Service had to wait until the survey was completed within the primary limits of the land grant to the Northern Pacific Railroad. This created a "perplexing administrative difficulty," especially concerning a 24-mile block of unsurveyed land in the Swan Valley. Until the GLO completed the surveys, homesteaders had to pay the high cost of surveying when applying for patent (W. B. Greeley to The Forester, 31 March 1910, 2300 Rec and Lands - General Corr 1910, RO).

In 1924 T. M. Wiles analyzed the homesteading situation in the Upper Swan Ranger District. He said, "many of the claimants wanted a homestead but it is doubtful if they really intended to make homes of them," and reported that many had returned to their railroad jobs that they held while performing their "so-called homestead duties." Of a total of 112 claims on the district, there had already been 247 filings. He classified the claims as follows: 61 abandoned or deserted after issue of patent; 8 actual homes of owners, from which livelihood was principally derived; 10 temporary stopping places of owners while unemployed; 11 homes of families whose owners worked elsewhere; 15 apparently abandoned prior to final proof; and 7 unperfected entries on which families resided but the livelihood came mainly from outside work. Obstacles included much more work clearing than the settlers realized, poor crops, and no available market. Willis reported that most of the claimants did as little work on their claim as possible, got a reduction in the area required to be cultivated, made final proof, and moved elsewhere, "thus defeating the intent and purpose of the homestead law in at least eight-five percent of the cases" (Wiles 1924: 5).

A number of Swan Valley homesteaders worked during the 1910s for the Somers Lumber Company on the large timber sale in the valley while living on their claims. After that sale, several small sawmills in the Swan in the 1920s and 1930s provided a number of jobs. Some people had taken up homesteads in order to get away from mill work, but they had to return to it in order to survive. By 1919, at least 70 homesteads had been located. Social events included Saturday night dances and fourth of July parties at the guard station at Holland Lake (24LA202, FNF CR; Beck 1981; Wolff 1980:54).

One of the well-known homesteaders in the Swan was Ernest Bond, who came to the Upper Swan Valley in 1894 to improve his health. He was an early forest ranger in the area, and he and his wife lived in the Swan Lake community for many years. Many of the early settlers of the Flathead Valley were Civil War veterans. "Old Man" Morley was a Union soldier who homesteaded at Morley Point on Swan Lake. Up the Swan River six or eight miles there lived a Confederate soldier named Gildart. When the two veterans met, they never spoke (Flint 1957:30; Craney 1978).

A good example of a proposed homestead that the Forest Service rejected because it was nonagricultural was the application of Joseph Ducett. The land was located in the lower Swan and was under water most of the time. Ducett, a taxidermist and trapper, owned adjacent land on which he raised muskrats, and the forest supervisor felt that the land was well-adapted to muskrat farming and that Ducett planned to sell it to a company that was developing the area's fur industry (FNF Class).

One woman's claim to a Swan Valley homestead was rejected because the Forest Service was able to show that she did not reside on the homestead. The woman, Anna Lambert, owned an abstract company in Missoula, and the government obtained abstracts she had signed as proof that she lived in Missoula. In 1919 she relinquished her claim in the Swan (FNF Adj).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/flathead/history/chap11.htm Last Updated: 18-Jan-2010 |