|

Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960 |

|

TRANSPORTATION

Introduction

Travel along the western slopes of the northern Rockies was quite difficult and time-consuming until recent years. Dense forests, steep slopes, and extreme weather conditions prevented easy travel. The earliest travel routes through northwestern Montana were trails developed by Native Americans. By the 1880s, a handful of wagon roads had been built in the Flathead, and soon a few ferries and bridges, plus steamboats on Flathead Lake, improved the transportation network. The coming of the Great Northern Railway to the valley in 1891 offered greatly improved access to points along the line. By the 1920s, there was political pressure and funding available for improved roads for automobile use.

The Flathead National Forest continued to rely heavily on the use of pack animals and trails after the introduction of automobiles in the early 1900s because so much of its land was otherwise inaccessible. The Forest was one of the earliest to use airplanes regularly, because of its unusually large backcountry. Many Forest Service workers helped with trail construction and maintenance, and each ranger district employed packers to move supplies by horses or mules where needed. After World War II, however, the Forest Service began receiving funding to build roads, many of them designed for accessing timber-sale areas and some designed also with recreational use in mind. As the mileage of roads on the Flathead National Forest grew, the mileage of maintained trails dropped significantly.

Early Flathead National Forest trails that are no longer maintained can often still be followed through the woods, with the help of the worn tread and occasional blazes. Some of the early roads have been blocked off, but these can still be easily followed on the ground.

Early Trails

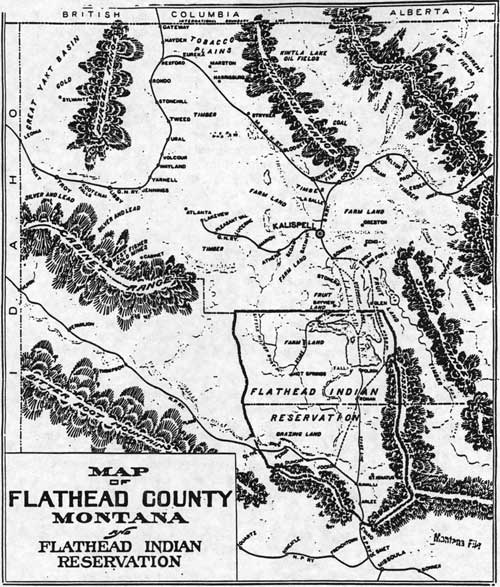

Native Americans traveled through the mountains by conforming to the natural routes of travel. If time, distance, and elevation changes were not determining factors, they followed high, open ridges, the edges of high river terraces, or game trails. Many trails regularly used by the Kootenai in the Flathead Valley originated near the mouth of Ashley Creek (a few miles southeast of today's Kalispell). Native American trails in the area did not receive a great deal of use in the 1800s because their population was not very high. The number of Kootenai in both divisions and all bands was probably about 1,000 in 1800, just before Euroamericans came into the area (Fredlund 1971:43: Braunberger & White 1964:57: Smith 1984:55).

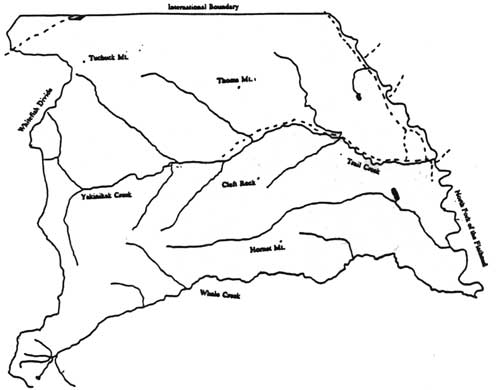

In the 1800s the Salish and Kootenai traversed the Flathead area on their semi-annual bison-hunting expeditions, until the buffalo were nearly exterminated. They traveled both on horses and unmounted, and in the winter they traveled on snowshoes. Plains groups, particularly the Blackfeet, crossed from east to west to raid for horses. All groups also made trips into the mountains for hunting, fishing, and gathering (Fredlund 1971:43; Malouf 1952:46). They favored camping areas such as Schafer Meadow and Gooseberry Park that provided both horse feed and game to hunt (see Figure 37).

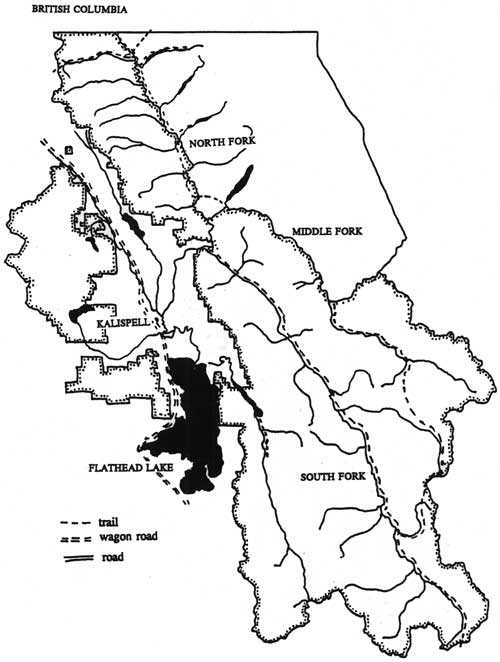

|

| Figure 37. Map of reported Native American trails in Flathead Valley area (Vaught Papers 1/L; Braunberger & White 1964:plate 19; Graetz 1985:83). (click on image for a PDF version) |

The length of time the verified Native American trails were in use is unknown. A 1900 description of trails existing in the area's mountains before 1898 is as follows:

There are old blazes in the mountains indicating old trails that must be 40 years old and while they are all blown over, still are a certain guide in going through the country. The South Fork country about 40 or 50 years ago, was the through route of the Hudson Bay Company from the North-west to the South-east. The Indians have also been through this country for years and while their trails are not open and very hard to follow yet in a pinch a man can work his way through (J. B. Collins to GLO Commissioner, 24 August 1900, entry 44, box 4, RG 95, NA).

The routes of various trails changed along with variations in the timber and wildlife conditions. According to a Blackfeet tribal leader in 1853, Marias Pass had not been used for many years, but formerly it was almost the only thoroughfare used by Native Americans in crossing the Continental Divide. Frank Liebig reported that Marias Pass was used very little by Native Americans because the area from the pass west to Fielding and Java was a "poor country for game" for a long time. Nyack Creek, on the other hand, had "all kinds of elk and sheep." He said, "I think the abundance of game lured the Indians across these passes." From Java down to Belton, before the railroad tote road was built in 1891, "it was a hard Canyon to get through, no game no horse feed, no trail, and a trail hard to maintain in a rough and cliffy country." The route was also practically obliterated with downed timber (Sheire 1970:75-76; Vaught papers 1/L).

Wagon Roads

For many years the main routes for people and supplies into what is now Montana were from the south through Salt Lake City, from the east by wagon trains, or by pack trains from Walla Walla, Fort Colville, or even San Francisco. In the early 1860s travelers began to use the Missouri River seasonally. The first steamboat had navigated the river from St. Louis to Fort Benton by 1859. The arrival of the Great Northern Railway in Montana heralded the end of steamboat travel on the Missouri River (Paul 1963:54). Travel within the state for many years centered on pack horses. As roads were carved through the woods of western Montana, travel by team and wagon began to be possible, although often still challenging.

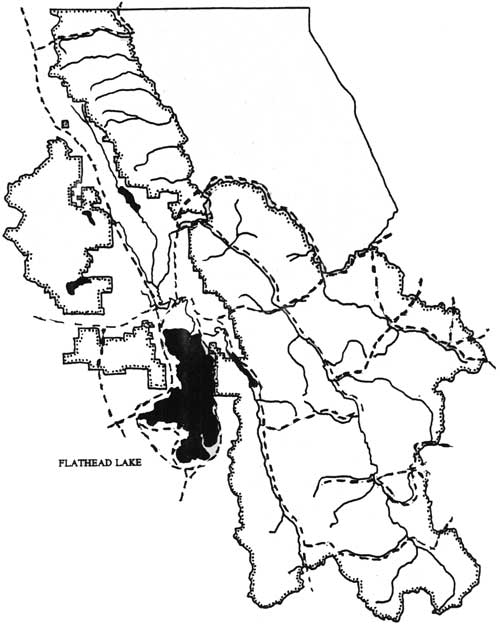

The Mullan Road was built as a wagon road from Fort Benton to Fort Walla Walla. The road was finished in 1862, just as the gold rush got under way; miners and a few settlers travelling to Oregon Territory kept it busy. Soon, roads were built from the south. The northern offshoot of the Oregon Trail was the Bozeman Trail, which extended from a fort in Wyoming to Virginia City, Montana, and was popular beginning in 1864. The Fisk wagon road was the northern overland route, used first in 1862 (see Figure 38) (Athearn 1960:87-88, 91; Toole 1959:85, 88-89).

|

| Figure 38. Major roads and trails in Montana after 1850. Steamboats traveled up the Missouri River from St. Louis, Missouri, to Fort Benton (from Toole 1959). |

In 1865 Governor Edgerton signed an act incorporating the Fort Benton and Kootenai Wagon Road Company, which planned to build a wagon road from Fort Benton to Marias Pass and on to the intersection with the Fort Steele-Kalispell Trail. Blackfeet hostility, however, led to the toll road project being dropped, and the charter was later cancelled (Elwood 1980:22).

A number of the early wagon roads were built over Native American trails, as they were already somewhat cleared and were often the best route to take through an area. One of these was the Fort Steele-Kalispell Trail (also called the Tobacco Plains Trail or Road), used by miners going from the Missoula area to mines in British Columbia (see Figure 39). That route had been used for a long time by Native Americans traveling between the Bitterroot Valley and the Tobacco Plains area (O. Johnson 1950:16).

|

| Figure 39. Freighter on Fort Steele-Kalispell trail (courtesy of Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula). |

In 1891 early settler Henry Bierman traveled this route with a team and wagons from Spring Prairie, near today's Kalispell, to Tobacco Plains in 1891. "By going ahead with an ax and cutting timber and brush and then following up with the teams, we made Ant Flats in 13 days. Some places we had to let the wagons down with ropes." In 1893 he was hired to be the supervisor of a road improvement crew on this rough road (Bierman ca. 1939:41-43).

During the construction of the Great Northern Railway, vast amounts of freight were brought to the Flathead Valley via the Northern Pacific Railroad to Ravalli, by wagon to the foot of Flathead Lake, and then by steamboat to Demersville. Supplies for Canadian Pacific Railroad workers in British Columbia were also brought by freighters along this route and then taken by wagon to Canada. This freighting to Fort Steele continued long after the railroad reached Kalispell (Elwood 1980:107).

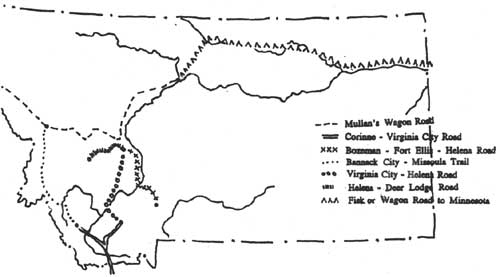

Until the late 1880s and the rise of Demersville, Flathead Valley residents bought many of their supplies at trading posts south of Flathead Lake or in Missoula. Until steamboat travel on the lake, all travelers followed a rough trail along the west side of Flathead Lake. By 1885, steamboats connected the foot of the lake with the upper Flathead Valley and points between (see Figure 40). The first boat, the Swan, sometimes took as long as a week to travel the length of the lake. Steamboat activity on the lake peaked in 1915, when more than 20 boats were operating. The steamboats on Flathead Lake were used as a connecting link between the Northern Pacific Railroad on the south and the Great Northern Railway on the north (see Figure 41) (Biggar 1950:115; Elwood 1976:60-61).

|

| Figure 40. Mary Ann and State of Montana at Demersville, 1891 (courtesy of Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula). |

The completion of the Northern Pacific line into Polson in 1917, and the increased use of automobiles, greatly reduced the demand for lake transportation, and passenger steamboat travel on Flathead Lake ended about 1925. Lumber company tugboats continued operating on the lake into the 1940s, however (Bergman 1962:78-79; Elwood 1976:61).

By 1888 a mail and passenger stage line connected Ravalli with Demersville. The trip took four days round trip and was popular during cold weather when the steamboats could not make their runs. The road along the east shore of Flathead Lake was built by convict and settler labor in the 1910s, although a rough wagon road had existed before then (Bergman 1962:64; Robbin 1985:28).

Travel in the Flathead Valley in the 1880s is described vividly by Margaret Rising, who had a ranch near Bad Rock Canyon in 1887. "There were no fences or roads at all and we just went the best way we could find across the bunch grass and through the heavy timber. We had a blazed trail through the timber so that we could get a team through and not hit too many trees and stumps" (Johns 1943:III, 41).

Gradually, settlers built bridges or operated ferries at river crossings. The Holt ferry was the first on the Flathead River, and it was not replaced by a bridge until 1942. A number of important bridges were built in the 1890s, including the Old Steel Bridge near Kalispell (1893), the Red Bridge near Columbia Falls (1896), and the Middle Fork bridge at Belton (1897) (Flint 1957:7; Robinson & Bowers 1960:62; Blake 1936:2).

The Flathead Valley was not directly accessible from the east until 1890, when Great Northern Railway contractors began building a wagon road known as the "tote road" from Bad Rock Canyon to the summit at Marias Pass for hauling their supplies. By the spring of 1891 a stage line was running between McCarthysville, near the summit, and Demersville. This was probably short-lived because the railroad came through later that year and the town of McCarthysville soon faded away. Henry Bierman reported that it took him 10 days to travel from McCarthysville to Columbia Falls with his team in 1891. During the summer of 1891 John Kennedy furnished the beef for the construction camps. Cattle were driven from Two Medicine and herded in corrals along the route. The cattle were slaughtered near the regular camps and the remains left there. Grizzly bears would be attracted to these piles of hides and offal, so people would hunt bear at these locations (Inter Lake, 14 November 1890 and 27 March 1891; Bierman ca. 1939:40-42).

The men at railroad construction camps denuded the surrounding hillsides of timber, consumed vast quantities of wild game, and started numerous forest fires. They also attracted all kinds of entrepreneurs and dealers to the area, including smugglers. For example, when the railroad was being built through the Flathead, the North Fork provided a route for horse thieves, smugglers, and for Chinese and opium to cross the border (DeSanto 1985:26).

Some of the valleys in the Flathead had difficult access for many decades. To travel to the Swan Valley in 1918, for example, one followed a 7-mile wagon road from Bigfork to the foot of Swan Lake and then took a boat up the lake (in the summer) or a 13-mile pack trail along the east shore (in the winter). From the south, a road/trail led from Ovando to Swan Lake. Early trips from the Swan Valley to Missoula generally took five days by wagon (Flathead National Forest "General Report" 1918; Wolff 1980:54).

Railroads

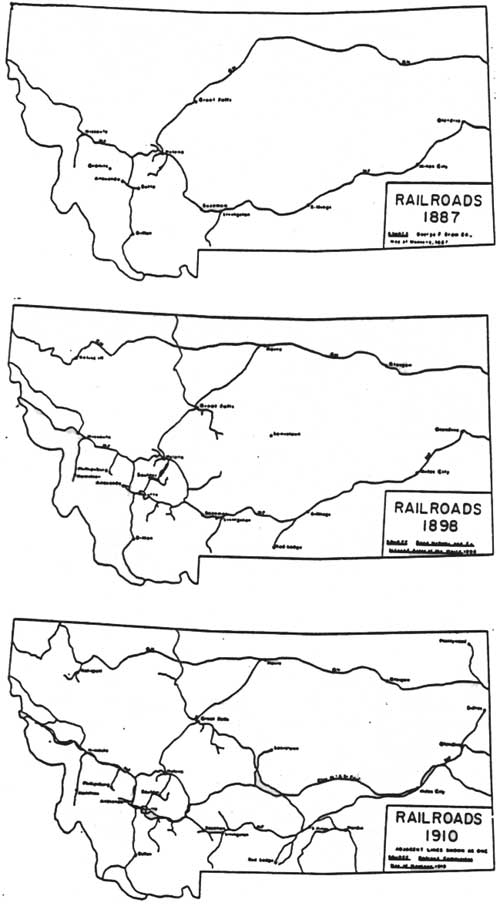

The transcontinental railroads had a tremendous influence on the development of the West (see Figure 42). With the coming of the Great Northern Railway to the Flathead Valley in 1891, residents enjoyed national rather than local markets for their products. During the Klondike gold rush of the late 1890s, business boomed throughout the Pacific Northwest as supplies for stampeders were shipped by railroad to jumping-off points like Seattle.

|

| Figure 42. Railroad routes in Montana, 1887, 1898, 1910. The new Great Northern Railway route built 1903-1904 and still in use is shown on the 1910 map. The main line of the Canadian Pacific Railway passed through Calgary and over Kicking Horse Pass far to the north (from Alwin 1972). |

By 1889 the Great Northern Railway had reached Havre, east of the Rockies, but the company still did not know exactly what route it would take across the Continental Divide. James J. Hill asked location engineer John F. Stevens to find out whether Marias Pass existed and could be used as a railroad route, as it was the most direct of all proposed (it was shown on an 1887 GLO map of Montana). Besides the Marias Pass route, railroad officials considered three other possible paths across the Rockies: along the North Fork of the Sun River; west from Butte across the Bitterroots; and along the South Fork of the Sun River over Rogers Pass to Missoula. Stevens traveled to the top of Marias Pass with a Kalispel (Native American) guide and reported favorably on the pass's potential. Meanwhile, Charles F. B. Haskell examined the western approaches, including the route west of Kalispell across what is now known as Haskill [sic] Pass into Pleasant Valley. In 1925 the Great Northern erected a bronze statue of Stevens at Marias Pass, commemorating his 1889 winter trip to the summit (he did not himself claim to have been the first Euroamerican to have crossed the pass) (Hidy 1988:74; J. Stevens 1935:672, 674; Haskell 1948:3).

For a variety of terrain and economic considerations, the Great Northern Railway chose the route across Marias Pass for crossing the Divide. On January 6, 1893, the last spike was driven on the Great Northern transcontinental line between Minnesota and the Pacific Ocean (Hidy 1988:74, 83).

In 1904 the Great Northern Railway relocated its main line between Columbia Falls and Jennings (near Libby). The division point was moved from Kalispell to the new town of Whitefish, creating a shift in population and to some extent in economic activity in the valley. At least one Flathead Valley old-timer grumbled that guides and trappers had recommended that route back in 1891 to James Hill, but "the wise boys in St. Paul said it was too far north." Some people with businesses along the abandoned main line sued the railroad. Stock raisers west of Kalispell and a Pleasant Valley lumber mill owner settled for damages to their businesses with the railroad company (City of Kalispell 1921:42-43; O'Neil 1955:151; "Old-Time Flathead Tales" 1939).

Between 1910 and 1916 several different schemes to connect the upper and lower valleys by railroad were seriously considered. The Northern Pacific did build tracks to Polson in 1917, but a line along Flathead Lake never materialized. In the early 1890s A. B. Hammond of Missoula promoted the idea of a railroad line that would compete with the Great Northern Railway. He hoped for a branch line of the Northern Pacific that would extend to the northern end of Flathead Lake, and the company agreed to build it if private interests could raise $100,000. The money was not raised, and the line was never built (Biggar 1950:122; Coon 1926:129).

Other railroad routes that did not materialize included one connecting the North Fork of the Sun River with Bowl Creek, the Middle Fork, and Coram; the Flathead Interurban Railway which would have connected the major communities in the Flathead Valley (ground was broken for this in 1911); a line from Bonner through the Swan Valley and up the North Fork to Fernie, B. C. (two routes were actually surveyed in the North Fork in 1909); and a line to run from Ravalli to Demersville to the coal fields in the North Fork (Elwood 1980:147; Graetz 1985:90; Ingalls ca. 1945:5). These projects were generally aimed at reaching particular natural resources that might offer the chance of bringing in great revenue.

The Canadian Pacific Railroad reached Calgary in 1885. Before the main line was built, most of the mail addressed to the Kootenay area of British Columbia went through the United States with American postage. A spur line from Fernie to Coal Creek was built in 1898 and ran until the mines closed in 1958. The railroad proposed building all the way south to the international boundary but never did so (Beals 1935:19; Fernie Historical Association 1967:39, 41).

Automobiles

The first cars were delivered to the Flathead Valley ca. 1905. In 1910, 60 Kalispell residents owned autos, and in 1919 the Flathead Valley could boast of about 2,000 automobile owners. Through the 1920s automobile driving in the Flathead Valley was still primarily a recreational activity, although doctors and other businesspeople used cars and trucks for their work. Building good roads was rationalized initially for the economic benefits and for the contributions to national defense, but recreational benefits underlay much of the early demand for highway improvement. In fact, the Good Roads Movement had been established in 1888 by the League of American Wheelmen (bicyclists) (McKay 1993:14; Jakle 1985:120).

Early county road construction mostly involved short-haul dirt roads built without the advice of engineers. Most of these roads were impassable during periods of heavy snow or spring thaws. Taxpayers could either pay cash to support the roads, or they could work on the roads themselves in lieu of payments (Wyss 1992:13).

The State Highway Commission first met in 1913, and until 1917 it was restricted from cooperating financially with the counties in a road construction program because of a lack of funds. The Commission did allow a limited amount of money to counties for road construction, and it purchased and equipped eight teams for use by prison forces on road construction (Montana State Highway Commission 1943:11, 12).

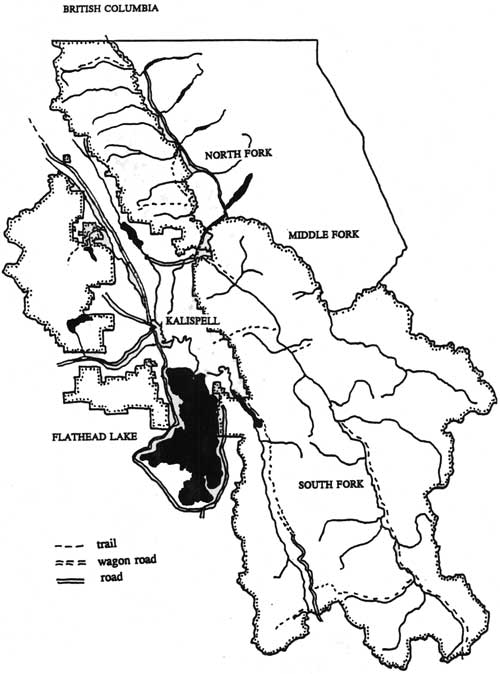

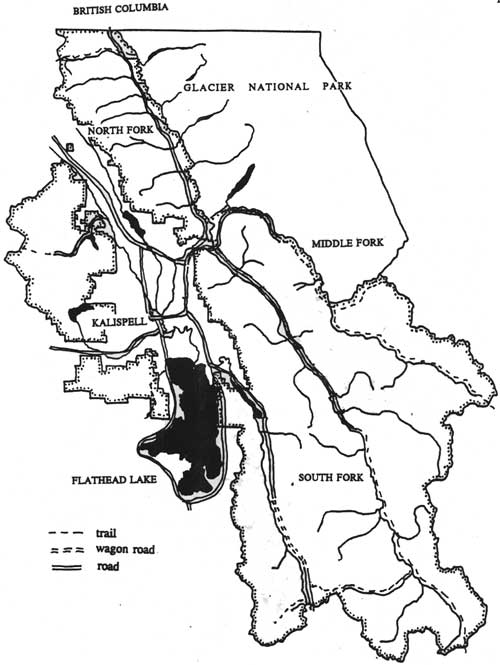

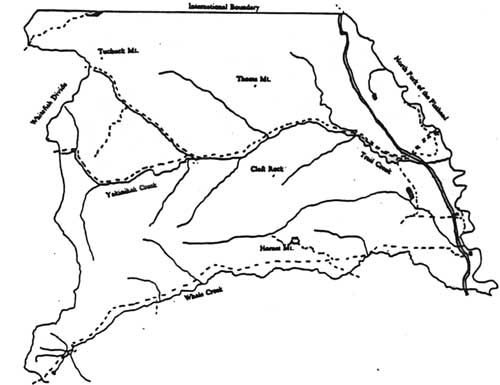

In 1917 the Montana legislature initiated a uniform system for construction and improvement of the main highways of the state. Early State Highway Commission contracts required a 22' roadway. In 1927 the state assumed the responsibility for snow removal (Wyss 1992:25, 31, 35). In the 1920s the federal government spent unprecedented amounts on road and highway development. The completion of several automobile roads greatly affected transportation patterns in the Flathead Valley. These included the highway over Marias Pass (1930), the Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park (1932), and the Swan Valley highway (1958) (see Figures 43-48).

|

| Figure 43. Primary roads and trails in area of present Flathead National Forest, 1898. (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Figure 44. Primary roads and trails in area of present Flathead National Forest, 1908 (Blackfeet National Forest) and 1912 (Flathad National Forest). (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Figure 45. Primary roads and trails in area of present Flathead National Forest, 1928 (Blackfeet National Forest) and 1927 (Flathead National Forest). (click on image for a PDF version) |

Forest Service Trails

An early, overriding job of forest rangers and guards on the Flathead National Forest was the creation of an effective transportation system. Because of budget constraints and the steep, rugged terrain, they generally built trails rather than roads. Until 1905, while the forest reserves were still administered by the GLO, supervisors did not bother to develop plans for road and trail systems; instead, rangers constructed trails to meet immediate needs. Some of the early "trails" were just blazes hacked through the woods. As ranger Jack Clack commented about traveling in the South Fork in 1907, "Trails... were considered a luxury anyhow, something very nice to have if you could afford it but not an absolute necessity." H. B. Ayres reported in 1900 that on the Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve (south of the Middle Fork) the underbrush was generally not dense and that one could ride horses anywhere except in damp ravines with abundant yew (Caywood et al. 1991:20; Clack 1923a:6; Ayres "Lewis & Clarke" 1900:45).

Forest Service trails generally were designed to follow the shortest route between two points with a minimum of elevation change (usually along river bottoms through thick lodgepole and undergrowth). The best location for trails was debated over the years. In 1929 a Flathead National Forest employee argued that trails should not be built along creek bottoms but should be located on ridges because ridge trails would give a smokechaser more chance of spotting and then finding fires. Ridge trails also cost less to construct than river trails, although spur trails to water were required (Fredlund 1971:43; Wiles 1929: 5-6).

The purposes of Forest Service trails were fire control, administration, grazing, and recreation. According to a 1935 manual, "Well-balanced work, not polish, is wanted." The manual recommended locating trails on southern exposures, ridges, benches, natural openings, open timber, and in light stands of brush whenever possible (USDA FS "Forest Trail Handbook" 1935:5, 7-8, 11, 14). Crews built bridges to eliminate difficult stream crossings (see Figure 46).

|

| Figure 46. Fitting the abutment timbers on the Big Prairie bridge over the South Fork, 1922 (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

Although most trails were originally built for fire protection purposes, some - especially in the Lake McDonald area - were built specifically to open up the backcountry for tourist use. Trails were constructed to different standards depending on their anticipated use. Glacier View Ranger District packer Bill Yenne described a "way trail," the lowest level of construction, as "scarcely passable for a jackrabbit" (Liebig 1936:15; Yenne 1983:32).

In 1900 there were about 200 miles of old but passable trails on the South Fork and its tributaries. The regional supervisor reported that "Our forest force have taken a great many of these old trails and changed them, making shorter cuts, or avoiding swamps and steep hills. In making this estimate I cannot call them open trails, but trails that can be followed through the country" (J. B. Collins to GLO commissioner, 24 August 1900, entry 44, box 4, RG 95, NA). Travel remained slow at best, even in areas no longer considered remote.

One of the early official trails in the Flathead National Forest went 21 miles from Ovando to the Danaher Basin. It was completed in 1903. In 1906, rangers were stationed for the first time at the head of the Spotted Bear and White Rivers, creating a need to build trails up those streams. In that year, rangers "pushed a trail of sorts up river as far as Spotted Bear, and from the head of the river down to Black Bear," but there was no trail between the two. This South Fork trail was the main route through the early forest reserve south of the Middle Fork. In 1900 there were about 135 miles of trail on the Swan River, plus about 12 shorter trails ranging from 10 to 30 miles in length (Flathead National Forest, "Informational Report" 1939; "Reports of the Section of Inspection," Elers Koch, 28 November 1906, RG 95, NA; USDA FS "Early Days" 1944:101; J. B. Collins to GLO commissioner, 24 August 1900, entry 44, box 4, RG 95, NA).

In 1920 a forest inspector felt that the trail mileage on the Flathead National Forest was still "surprisingly low" and that vast areas still had no trails. He said much of the trail money was spent on the main river trails instead of on lateral trails and criticized the rangers for building two and even three trails along the South Fork in an unplanned "process of evolution." He mentioned that although 1,000 trail signs had been painted they were not yet posted, leaving some major intersections unmarked (Elers Koch, 19 July 1920, Flathead 1920-23 Inspection Reports, RG 95, FRC).

By 1936, the Flathead National Forest had constructed 4,500 miles of trail. At that time there were only 360 miles of highway and Forest Service development roads on the Forest. In the 1930s, according to Pat Taylor, "Everything was walking. Men walked on these trails. The assistant ranger and the ranger rode and the packer rode but the rest walked" (Blake 1936:2; Taylor 1981).

For years after 1918, a large portion of road and trail funds were used in Region 1 to build trails into the backcountry (USDA FS "History of Engineering" 1990:20; R. West 1938:1). Trail mileage on the Flathead National Forest was declining by the 1950s, however. In 1955, trail mileages were as follows:

Big Prairie: 485 miles

Condon: 278 miles

Coram: 402 miles

North Fork: 421 miles

Schafer: 405 miles

Spotted Bear: 543 miles

Swan Lake: 263 miles

Tally Lake: 261 miles plus 92 more on Northern Montana Forestry Association protection area on Tally Lake RD

(FNF "Transportation System Inventory" 1955).

The total mileage was 3,150 miles. Thirty years later the trail mileage on the Flathead National Forest had dropped to 2,146 miles (FNF "Forest Plan" 1985:S-15).

The Middle Fork trail (along the railroad tracks) was also an early priority; by 1906 Forest Service workers had cut it out except for three miles just below Java, but its completion was delayed by the deaths of rangers McElroy and Harbin in a railway accident. Professor Morton Elrod of the University of Montana filed a complaint about the condition of this trail, but the inspector commented that "no one but a very nervous man or one unaccustomed to the mountains would give the trail a second thought in going over it with a pack outfit" ("Reports of the Section of Inspection," Elers Koch, 28 November 1906, RG 95, NA).

By far the easiest transportation route for early forest rangers was the Great Northern Railway tracks, and rangers used gas speeders along the tracks to cover the area from Summit all the way to Eureka. In the Middle Fork, fire crews were ordered by wire from Kalispell and sent in by train to the closest point (USDA FS "Early Days" 1955:73-74).

In the early years, some Forest Service workers attempted to use rivers for transportation corridors, as some of the early trappers had done. In 1915, for example, several timber cruisers decided to return to Coram from the Riverside Ranger Station on the South Fork by raft. One went over a waterfall and ended up snowshoeing the rest of the way out (USDA FS "Early Days" 1955:81-82).

An attempt at alternative transportation methods was made in 1923, when rangers Henry Thol and Ray Trueman tested sled dog teams in the backcountry. On their first trip, they traveled from Coram up the South Fork with 250 pounds of supplies, including two blankets for each man, coming out six weeks later at Holland Lake. The dogs proved unsatisfactory on sidehill trails in rough terrain (USDA FS "Early Days" 1962:209; Thol 1936: 13).

Because of its remote districts, the Flathead National Forest used airplanes regularly by the 1930s. In 1932, one hundred thousand pounds of freight was delivered to a Flathead National Forest landing field at less cost than using a combination of railroad, trucks and pack trains. By 1939, the Flathead National Forest had 10 airplane landing fields. Helicopters came into local use in 1954. They were practical both in regular forest duties and in bringing sick or injured people out of the backcountry (Headley 1932:183; Flathead National Forest, "Informational Report" 1939; Shaw 1967:99).

Forest Service Trail Construction and Maintenance

Early Forest Service trail crews consisted of 10-12 men, including a cook, while later crews generally consisted of 3-5 men who did their own cooking. Trail crews typically lived in tent camps, which they moved every 7-10 days (see Figure 47). The men were trained and kept available for fighting fires (Swan River Homemakers Club 1993:339; Taylor 1986).

|

4 axes 1 5—gallon man-pack bag 2 2-1/2—gallon water bags 1 crow bar (where needed) 12' log chains (where needed) medicine chest cap crimpers (where needed) 4 8" files 4 10" files 1 U.S. flag Beatty trail grader (where needed) claw hammer 4-lb falling hammer axe handle 2 mattock handles 2 saw handles 1 brush hook 1 timekeeper's kit 1 mattock 1 cobbler outfit 1 saw-filing outfit 2 complete smokechaser's outfits 1 peavy 2 mattock picks 1 trail plow (where needed) 1 pack frame 5 1/2' crosscut saws 2 LHRP shovels 3 pocket carborundum stones 2 falling wedges 2 wash basins 1 wash board 1 2—gallon boiler 4 granite soup bowls 1 10—quart canvas water bucket 1 can opener 1 alarm clock 2 medium bread pans 1 bread dish |

7 nested cups 1 8' canvas table top 8 table forks 1 pancake griddle 2 2—quart kettles 2 4—quart kettles 1 6—quart kettle 1 butcher knife 1 paring knife 8 table knives 6 lbs assorted nails 3 yards 46"-wide white oilcloth 6 dessert spoons 1 mixing spoon 8 table spoons 1 complete telephone 3 pie tins 8 50-lb flour sacks dish toweling wash tub 1 cake turner 1 10x12' fly 2 10x12' tents 30 wool blankets extra bed (for forest officer) 5 tarps 1 Lang or sheep cook stove 5 stovepipe joints 1 3—quart dish-up pan 3 2—quart dish-up pans 1 medium fry pan 2 large fry pans 8 enamel plates 1 coffeepot 12 cloth lunch sacks 1 meat saw 4 yards cheesecloth screen 1 salt shaker |

| Figure 47. Equipment considered necessary for a five-man Forest Service trail crew in 1935 (Fickes 1935:T-13-15) |

In the 1930s, the main job of trail crews was logging out trails. One man would go in front with an ax and cut out the trees up to 6-8" in diameter, and two more would follow with a cross-cut saw. They would cut standing and down "pack bumpers" (trees that mules carrying loaded packs might bump into), clear brush, remove snags left by fires, do minor drainage work, kick rocks out of the trail, and freshen up trail blazes (Taylor 1981).

Some trail crew workers did get injured on the job. One compensation case report submitted by a trail foreman featured poor grammar but was succinct: "Please fix this man up with comp. Has fell and hurt his knee. Slick shod. Bad stuff" (Fremming 1931:8).

By 1930 the Blackfeet National Forest was using "gyppo" (contract) trail crews as well as day crews, and they found that the gyppo system cost 1/3 less with no difference in quality. Pat Taylor remembered a trail crew of five German immigrants working on the Tally Lake Ranger District in the 1930s. This crew was unusual because the men furnished their own saws (bow saws, or Swede fiddles) ("Gyppo Work" 1930:7; Taylor 1986).

Way trails, built to the lowest standard, were designed for extreme fire emergencies, not for everyday use. Way trails were cleared to the minimum width required to allow a pack string to pass through, and the maximum grade was 15% (which trail crews checked with a level). Tread work was held to a minimum because pack animals would establish it, and few bridges were built because the stock could ford most waterways. In 1928 the Flathead National Forest built 10 miles of primary trails, 81 miles of secondary trails, and 312 miles of way trails, for a cost of $522, $178, and $113 respectively. Way trails were clearly the cheapest and easiest to construct but certainly not the best for traveling (Taylor 1986; USDA FS "Forest Trail Handbook" 1935:15; Wiles 1929: 6-7).

The Forest Service blaze in the 1930s had a 4"-high mark on top, and then 4" below it was a lower blaze 8" in height. Workers cut the blazes 30' apart at eye level facing both directions on the trail. Early trail signs were made of enamel and had black letters on white backgrounds. By the 1950s the Forest Service was using imprinted aluminum or routed wood signs. The Forest Service used to post mile boards on the trails (Taylor 1986; 1956 inspection report in 24PW1003, FNF CR; Howard 1984).

The Forest Service experimented with a number of mechanized tools for trail building and maintenance and even helped sponsor some industrial development work for particular machinery. For example, in 1923 the Flathead and Blackfeet National Forests performed field tests of the Wolf power saw (a forerunner of the chain saw). They concluded that the saw had "very real possibilities for use in areas where heavy sawing jobs exist," but that it was not suitable for light work. In 1950 chain saws were not being used extensively for trail work because they were only needed intermittently; they were more practical in heavy blowdowns. The cutter bars at that time ranged in size from 14" to 6' in length (Frank J. Jefferson, 3 August 1932, Flathead Inspection Reports, RG 95, FRC; USDA FS "Trail Handbook" 1950).

In 1925 the Blackfeet National Forest bought six of the "new model" Beatty trail graders, which they used for trail and road construction, and they also tested horse-drawn plows (see Figure 48). They determined that the horse-drawn plow-and-grader system could be used in all terrain except solid rock, even in heavy beargrass. The cost of construction of over 75 miles of trail built with these plows and graders was 1/5 to 1/4 the cost of hand labor. The Flathead National Forest reached similar conclusions despite "considerable opposition" to the new tools. Popular for many years, the Beatty trail grader was last manufactured in 1952 (USDA FS "Trail Handbook" 1950:34-35; "Use Horses" 1925:14-16; Mendenhall 1926:4).

|

| Figure 48. The Beatty trail grader (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

Eventually trail maintenance within the Forest Service became the responsibility of the Recreation department, reflecting the shift away from the original purpose of improved transportation networks for Forest protection (Caywood et al. 1991:66).

Forest Service Use of Pack Animals

Since most of the Flathead National Forest was accessible only by trails for many years, the Forest Service relied heavily on pack animals. At first, rangers were required to furnish their own saddle and pack horses.

The first pack animals purchased by the Forest Service for use in the Northwest were reportedly eight head of horses that Jack Clack brought to Big Prairie on the South Fork in 1907 or 1908. The experiment in breeding these horses failed, and the government subsequently purchased all of its stock. In those early years, according to one Flathead National Forest employee, the pack animal was generally a cayuse that "could be had for a song - even an off-tune song" (Frohlicher 1930:456-457; Caywood et al. 1991:25).

Jack Clack probably brought the horses to Big Prairie because of an inspection report in which Elers Koch commented that rangers on the South Fork spent 6-10 days on every trip out of their district for supplies. Koch recommended hiring one man to constantly deliver supplies with a government pack train from Columbia Falls to Ovando via the South Fork. This basic concept is still being followed in the Bob Marshall Wilderness between Spotted Bear and the Big Prairie and Schafer Work Centers (Elers Koch, 28 November 1906, "Report of the Section of Inspection," entry 7, box 4, RG 95, NA).

In many ways, packers and their stock were the lifeblood of the Forest Service. As Flathead National Forest employee John Frohlicher commented in 1930, "If a lookout, ranger, or firefighter is without tobacco, coffee, or even his mail, he is a discontented human being. The mule packs in whatever is necessary for his peace of mind and body" (Frohlicher 1930:456-457).

Horses were initially the pack animal of preference. In the early years, two men with 15-20 head of horses would work together on long pack trips. They usually herded them down the trail instead of stringing them together (Shaw 1967:23). During the 1910s, almost all Forest Service employees learned to pack a horse; horses were more tolerant of poor packers than mules. According to one Flathead National Forest employee:

mule packers are born, not made...The old heads couldn't stand the mules. They are now found somewhere out in civilization, cursing the animals that chased them from their jobs...The new packers [who used mules]...were better than smokechasers and rangers and lookouts. They admitted it, even though the lesser lights frequently rounded the mules up. Packers' heels are too high to allow much walking. Anyway, a smokechaser should have practice looking for mean things, like fires and mules, the packers reasoned (Frohlicher 1930:457).

According to long-time Flathead National Forest employee Charlie Shaw, packers generally preferred mules to horses for packing because they were more sure-footed, required less feed, could carry heavier loads, had a smoother gait, stayed with the bell mare at night, and would not try to rub their packs off against trees along the trail. On the other hand, mules tended to hide out when wanted, to bog down in muddy trails, and to do poor work logging and trailmaking (Benson 1980:22; Frohlicher 1930:458).

In the spring, pack animals destined for the Flathead National Forest were driven from their winter range near Flathead Lake. The Holt Ferry brought them across the Flathead River, with their destination the Echo Ranger Station corral. There the South Fork and Echo stock were cut from the herd, and the rest of the stock headed up the Swan the next morning. During the winter, employees at the station did all the tack and saddle repair for the Forest (Swan River Homemakers Club 1993:339).

"Main line" packers supplied workers in isolated districts so that they did not have to travel out of their area themselves. Each district also had its own packer, and all employees learned to pack short strings (up to five head). Backcountry ranger districts relied on the packers for food. The cook at Big Prairie in 1926, for example, recalled running low on food; he served ham with the mold washed off until the packer arrived. Most ranger districts had a large number of stock. Tally Lake, for example, had 32 head of horses and mules in 1930. At that time the Flathead National Forest (south of the Middle Fork) owned approximately 200 head of pack horses and mules (Montgomery 1982; Taylor 1986; USDA FS, "Flathead National Forest" ca. 1929).

The Coram Ranger Station, located at the north end of the Coram-Ovando supply line, served as the primary distribution point for the entire South Fork. By 1914, 20 tons of hay were harvested from a 10-acre field at Coram. The hay was used by government pack strings in the summer and for district rangers' horses in the winter. Coram served as district headquarters until it was consolidated with Hungry Horse in the late 1960s or early 1970s. Until at least 1956, the Big Prairie Ranger District cut enough hay for its own use, storing it loose. At that time the district did not have a hay baler, but in the 1920s it used a handmade baler. Spotted Bear also had a handmade baler in 1924, which it used in haying at Bruce Meadows (24FH443, FNF CR; 1956 inspection report in 24PW1003, FNF CR; 3 November 1924, Flathead Inspection Reports Region One, RG 95, FRC).

In the 1920s the Flathead National Forest had 10 main-line packers, each with a string of nine mules and a horse. The main-line route went from Coram Ranger Station up the South Fork to Spotted Bear, then on to Schafer and Big Prairie. The work centers and cabins along the route provided stopover spots for the packers. According to packer Toad Paullin, "There was no such thing as an eight hour day or coffee breaks. When you got one load there, you just turned around and went after another one." During the 1926 fire season, Paullin hauled supplies day and night for 55 straight days, sometimes reaching a fire camp only to find it had been burned out. One of Paullin's memorable packing feats was in 1955, when he hauled a 16' x 4' aluminum boat from Spotted Bear to Big Salmon Lake (see Figure 49) ("With 'Toad' Packing" 1982:20).

|

| Figure 49. Fire control officer Theodore W. (Toad) Paullin and a "short string" in Bob Marshall Wilderness, 1967, on ridge along trail to the old Picture Lookout point (photo by George R. Wolstad, courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Region One, Missoula). |

The packer would generally start out about 4 a.m. to locate his stock; he had to be a good tracker. The saddle horse would be picketed or hobbled, and the bell mare was usually hobbled, belled, and turned loose with the rest. Once he had wrangled the horses and mules, the packer would halter and curry the animals and put on feed bags. He would then take off the nose bags and saddle the mules. If he had not done so the night before, he would "manty up" the load, dividing the articles into side packs and tying them into packs with cargo ropes (see Figure 50) (Taylor 1988; Taylor 1986).

|

| Figure 50. Toussaint Jones packing a hot-water heater to a Flathead National Forest administrative site (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

By 1924, the Flathead National Forest was putting into effect the "Idaho plan" of replacing horses with mules and adopting the Decker saddle. The Decker packsaddle replaced the sawbuck and the diamond hitch (the last diamond hitch in the Forest Service was thrown in 1928). As Pat Taylor commented, "The 'Diamond Hitch' was being forgotten as fast as possible." The Decker saddle originated in Idaho during the turn-of-the-century mining boom there and was popular because a load that hit an obstacle would shift back into position. With the new system, eight mules to a string with a bell mare and the packer's saddle horse became the norm. The sawbuck saddle and diamond hitch continued to be used in Glacier National Park for a while longer (3 November 1924 memo, Flathead Inspection Reports Region One, RG 95, FRC; USDA FS "Early Days" 1976:43; Taylor 1988; Taylor 1986; Yenne 1983:6, 54; Shaw 1967:23).

During the 1929 fire season, an unusually bad year, Region One did not have enough mules to supply the need. The Forest Service hired 2,000 extra horses and used them to pack tools, food, and bedding to fire crews, working a total of 45,000 horse days. Part of the reason for the shortage of pack animals was that the stock that was formerly available for hire in the region was being replaced by automobiles and trucks (Frohlicher 1930:457; USDA FS, "Flathead National Forest" ca. 1929).

After the fire season of 1929, Clyde Fickes proposed establishing a Remount Depot for the region. In 1930 the Forest Service leased a ranch 30 miles west of Missoula, and that summer hired stock was sent out to the various Forests as needed. Soon the Remount Depot purchased its own stock. In 1934 the Forest Service bought a ranch, and the CCC constructed buildings at the new Remount Depot. The Flathead, Blackfeet, and Kootenai National Forests had been wintering their stock in the Big Draw near Flathead Lake for several years; the Remount took over that contract. The Remount also trained and sent out plow units (teams of draft horses used to cut a fireline with a plow). Each 10-mule pack string sent out by the Remount Depot supplied a 25-man fire crew plus a cook and packer, and the supplies included cooking utensils, canned goods, sides of beef and other food, and firefighting tools. Some of the canned food had inspirational slogans on them such as "Less Food in the Refuse Pail - Fewer Pack Mules on the Trail" (USDA FS "Early Days" 1944:56-60, 62; Benson 1980:4-7, 21; Howard 1984).

The Remount Depot was phased out beginning in 1953. Some of the reasons for its discontinuation included the use of smokejumpers (resulting in fewer large, remote fires), the much more extensive road system on the national forests, airplane cargo delivery, and the reduced use of lookouts (Benson 1980:31).

While the Remount Depot operation was a success for many years, aiding in the fire and general work of the region, other ideas from the regional office were not so popular on the district level. For example, in 1926 Regional Forester Evan Kelley hired a couple of bronc riders to break the mules at Big Prairie for riding (Kelley was trying to save firefighters the 40-mile walk from Spotted Bear to Big Prairie). The bronc riders "plowed up sections of the Prairie with their faces" until they quit. Only two mules could be ridden, and the firefighters continued to walk in (Frohlicher 1986:98-99).

Another time-saving idea of Kelley's also ended in failure. He wanted to reduce the time it took for packers to balance, manty, and load mules. To this end, he had a loading dock built at Spotted Bear with a pole, pulley, and rope to joist the packs up over the mules and lower them to the packsaddles. But, the mules "had to see two legs under the pack when it was coming towards them"; otherwise they broke into frenzied bucking. Even so, an experienced packer with a helper could reportedly load tools, bedding, and two days' rations for 30 men in about 20 minutes without the use of a loading dock (Frohlicher 1986:99-101; R1 PR 798, 29 May 1937).

Forest Service Roads

The lack of roads significantly limited the Flathead National Forest's ability to develop an area (i.e., to use the natural resources such as timber). As early as 1906, forest inspector Elers Koch wrote, "There is an excellent opportunity on this reserve to open up to sale large bodies of timber by the construction of roads up the main valleys. The Swan River and the South Fork of the Flathead are the two best propositions for work of this sort." In the early years, Forest Service workers helped on county road construction. In 1908, for example, Jack Clack was in charge of road reconstruction through Bad Rock Canyon, which required blasting through 1/2 mile of solid rock. Rangers worked on the job on "contributed time" (Elers Koch to The Forester, 18 November 1906, "Reports of the Section of Inspection," entry 7, box 4, RG 95, NA; Bloom 1933:2).

Before automobiles came into common use, there was little demand for the development of mountain roads. The improvement of Forest recreation roads was initially promoted by the federal government. In Montana, the Bureau of Public Roads supervised all major forest construction projects. The 1910 fires led the Forest Service to push for funding for more roads and other improvements such as trails and telephone lines. The general consensus was that poor transportation and communication systems allowed the fires to get so big (Wyss 1992:43-44; Baker et al. 1993:224).

In the 1920s the Forest Service adopted motorized transport, resulting in the consolidation of many ranger districts and aiding in moving men and supplies for firefighting. Region One bought its first automobile in 1917 (for the Custer National Forest). By 1940 the Flathead National Forest had approximately 32 forest trucks, pickups and cars, 10 pieces of road machinery, and fire pumpers (Baker et al. 1993:73; CCC: Inspection: General: Montana State: Camp S-208, RG 95, FRC).

Before 1912 the Forest Service did not have the authority or the funds to construct, maintain, or manage roads. In 1913 Congress gave the Forest Service the authority to spend 10% of the national forest receipts on roads and trails; the money had to be spent in the state in which it originated. For three years before the Federal Road Act of 1916 was enacted, the federal government provided funds in small amounts for the improvement of roads within the national forests. The Public Roads Administration, the Forest Service, and the State Highway Department combined to develop the forest highway system. The Federal Highways Act of 1916 defined forest roads and provided additional financing. This was the first money available for Montana's Forest roads; it was spent on the Bitterroot Big Hole Road. Beginning in 1921, Forests also received money for roads from the Federal Highway fund (Montana State Highway Commission 1943:59; Burnell 1980:1; Bolle 1959:139).

As defined in 1924, forest highways are sections of state, county, and other important public roads in and adjacent to the national forests that provide primary access to the Forest. They receive federal funds authorized for Interstate Highways, plus funds authorized especially for forest highways. Forest roads, on the other hand, are needed primarily for the protection, development, and administration of national forest lands. Forest roads fall into one of three categories: arterial roads (paved, two-lane: 5% of Region One roads); collector roads (1- or 2-lane roads used for access to timber or recreation: 20% of Region One roads); and local roads (minimum standard, single-lane roads used for a specific purpose such as timber or fire control: 75% of Region One roads). Forest highways on the Flathead National Forest in 1943 included the roads from Fortine to Olney, from the Forest boundary east of Columbia Falls to Glacier Park Station, from the Forest boundary south of Bigfork to the south Forest boundary, and from the Forest boundary at Swan Lake to the Forest boundary at Seeley Lake (Bolle 1959:138; Burnell 1980:1; Baker et al. 1993:225; Montana State Highway Commission 1943:58F).

One of the early forest road projects in Montana was the west side North Fork road. In 1917, Hartley Calkins located the road for some 30 miles, surveying across private ownership almost the entire way. In 1919 the county finished the work on the road from Columbia Falls as far as a couple of miles north of Polebridge, with local settlers working on the road in lieu of paying road taxes. The lower part of the road was built with four two-horse teams, plows, scrapers, and dynamite, and men threw the rocks out of the roadway with pitchforks (this was typical of road construction at the time). Forest Service construction work on the upper stretch of the road took place in 1921, and a new post office was established at Trail Creek. The county used a steam shovel to side-cast material on road widening projects until about 1931, when the steam shovel went over the bank and into the river near the mouth of Canyon Creek. After World War II the Forest Service began to maintain the west-side North Fork road for logging purposes, and in 1949 an agreement was signed providing for the county to maintain the road to Deep Creek and the Forest Service from there north to the Canadian boundary (Glacier View Ranger District 1981; Peterson 1977:6; USDA FS "History of Engineering" 1990:24, 47-48; Burnell 1980:3).

The roads through the Swan Valley and along the Stillwater River were also located in the summer of 1917 using the newly available funding. Settlers in the Swan Valley had been pressing authorities for some time for a road through the valley linking Swan and Seeley Lakes. In 1917 the Regional Forester considered the project "one of the most important in the state." The Somers Lumber Company had built roads between Swan Lake and Cilly Creek, and in 1917 a road was built between Lion Creek and Swan Lake. In 1922 the Swan River road was described as "a wagon track winding through the timber... impassable for an automobile, although cars have with great difficulty reached Holland Creek from the south." From Holland Creek to Goat Creek it was a "circuitous wagon track cut through the timber by settlers," with grades exceeding 20% in many places and with creek crossings made by dropping logs across the streams and flooring them with poles. The road had been developed largely by donation work from the settlers, with a small amount of financial aid from the counties and the Forest Service (F. A. Silcox to the Forester, 10 May 1917, in 1380 Reports - Historical - District 1, RO:5; Conrad 1964:27-29).

Until the road from Coram to Spotted Bear was built in the mid-1920s, it was a 90-mile, 5-day pack trip from Coram to Big Prairie. The road was built with horses hauling the materials and supplies, and road construction camps were located every three miles. The road to Spotted Bear was designed to be 9' wide but, according to a 1927 inspection report, it was actually built to an average width of 15' (see Figure 51) (USDA FS "Early Days" 1962:289; Green 1971:III, 108; Flathead Inspection Reports, Region One, RG 95, FRC).

|

| Figure 51. South Fork road near Upper Twin Creek, 1926 (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

A general road-building boom hit Montana from 1921 until the start of World War II, stimulated by massive federal spending on roads and highway development. The new roads allowed more recreation on the Forests and increased the value of the timber and mineral resources by bringing them closer to market. After the Federal Highway Act of 1921, roads were a separate line item in the Forest Service annual budget, which allowed the road construction program to expand in the 1920s (Wyss 1992:64; Caywood et al. 1991:35-37).

The first transportation planning on the national forests occurred in the late 1920s. At that time the focus was on fire control, but the uses of roads soon expanded. The transportation plans contained detailed information with economic justifications, plus a key to priorities for construction. Because there were few Forest Service timber sales then, logging roads were almost always of low standard aimed at serving proposed small sales. The Washington Office favored low-cost roads that worked well for fire control but were reportedly "useless" for logging. Eight-foot widths and steep grades were the rule (USDA FS "History of Engineering" 1990:21, 321).

From 1920-27 roads were constructed by first building a horse trail with pick and shovel. A draft horse pulling a two-way plow followed, then a horse-drawn Martin ditcher, which provided the tread for a small tractor pulling a grader. After repeated passes, the roadbed was built (USDA FS "History of Engineering" 1990:24).

At the beginning of the 1930s, Forest Service policy changed to building fewer trails in favor of building a great number of low-class, low-cost fire control roads known as "truck trails." The invention of the bulldozer allowed roads to be built cheaper than hand-built trails. Winter work at many CCC camps consisted of building roads along drainages, and this allowed Forest Service engineering to take on a larger role within the organization. Major Evan Kelley, a strong opponent of better roads, retired from the Forest Service in 1944. His retirement, combined with the growing demand for national forest timber, led to more construction of improved forest roads (USDA FS "History of Engineering" 1990:23-24).

Still, it took a long time for roads to reach the more remote areas of the Forest. Tally Lake Ranger District, for example, did not have any motor vehicles in 1931, and the only passable road on the district went from Whitefish on Highway 93 and then via the old Tally Lake Road to Star Meadow. In 1933 the CCCs extended this road to about 1/4 mile beyond Taylor Creek (a few miles south of Star Meadow) (Pat Taylor, 1975 interview, in 24FH41, FNF CR).

The Red Meadow Road in the North Fork was built about 1937 by CCC enrollees. As justification for the road, J. C. Urquhart explained that it crossed the Whitefish Divide "at a point from which there are numerous radiating trails; also a considerable mileage of telephone line is maintained from this point. In the event of fires firemen, firefighters, equipment and supplies, etc. can be routed in either direction along the Whitefish Divide (from the top) and dropped onto fires in the heads of drainages much more readily than would be possible without the road" (Urquhart to Regional Forester, 13 April 1938, Inspection Reports, Region 1, 1937-, RG 95, FRC). Forest Service inspectors, however, criticized that particular road for not being wide enough for buses and truck trailers, for lacking spur roads every mile leading to fire campgrounds, and for lacking turn-arounds for about 9 miles above the former CCC camp. It was built on a steep sidehill rather than in the creek bottom, where they felt it would have had greater timber and recreation value (27 December 1937 memo, Inspection Reports, Region One, 1937-, RG 95, FRC).

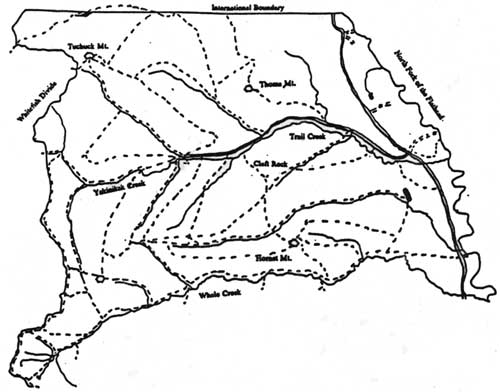

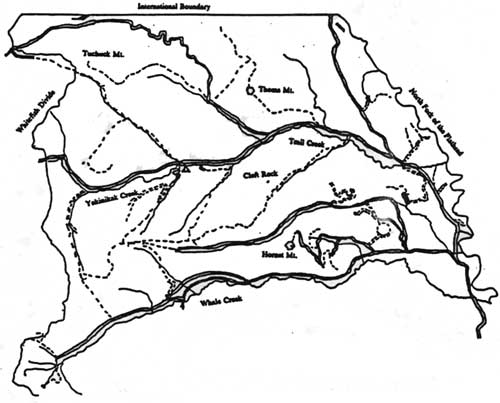

After World War II, the rising demand for timber, recreation, and more efficient fire control increased the demand for Forest roads in Region One, and as the road mileage increased, the mileage of maintained trails decreased (see Figures 52-55). Road and bridge construction became a major post-war effort, aided by new congressional appropriations and by an accumulation of county road funds. Regional Engineer Fred Thieme, described as a man who "always wanted bridges, roads, and buildings bigger and better than the design called for," was the regional engineer from 1936-1951. The new roads did help provide access to forest fires, but they also ironically increased the risk of human-caused fires (Baker et al. 1993:165; USDA FS "History of Engineering":77, 397).

|

| Figure 52. Trails and roads in the Trail Creek and part of the Whale Creek drainages in the North Fork, 1912. |

|

| Figure 53. Trails and roads in the Trail Creek and part of the Whale Creek drainages in the North Fork, 1928. |

|

| Figure 54. Trails and roads in the Trail Creek and part of the Whale Creek drainages in the North Fork, 1948. |

|

| Figure 55. Trails and roads in the Trail Creek and part of the Whale Creek drainages in the North Fork, 1963. |

The construction of the Hungry Horse Dam flooded the original road that followed the South Fork. Mountainside timber-hauling roads had to be substituted for the more easily maintained valley haul road. The Forest Service negotiated successfully with the U. S. Bureau of Reclamation for "replacement in kind" grades, width and curvature so that the new roads would better serve logging objectives. The main haul road on the east side of Hungry Horse reservoir was completed in 1952 and the west side road in 1954 (USDA FS "History of Engineering" 1990:86; FNF "Timber Management, Coram" 1961:39). These two roads were critical to the future development of the many miles of roads up the side drainages of the South Fork.

In 1952 Congress appropriated $4.25 million for road construction in Region One. Forest engineers subsequently upgraded many of the older roads and built new ones. In 1959, the Flathead National Forest road system claimed 1,139.5 miles. In 1985, the road mileage had risen dramatically to 3,941 (Baker et al. 1993:225; Charles Tebbe, Jan 1960, "Basic Facts, National Forests in Montana," 1380 reports - Historical - NF Facts, RO; FNF "Forest Plan" 1985:S-20).

Between 1952 and 1955, the North Fork road was rebuilt from Canyon Creek to Big Creek, and improvements were made to Whale Creek (see Figure 56). Roads into side drainages throughout the North Fork were also constructed during this period. This work was done to aid in the logging to control the spruce bark beetle epidemic in the area. As a result, in 1955 the southern terminus of the mail route was moved from Belton to Columbia Falls (where it still is). Much of the road system in the Swan Valley was also developed to salvage insect-infested timber. The location and construction standards were low (Burnell 1980:3; FNF "Timber Management, Swan' 1960:28).

|

| Figure 56. Fool Hen Bridge on North Fork Road (west side), 1953 (photo by W. E. Steuerwald, courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Region One, Missoula). |

Region One continued to push for timber access road construction funding through the 1950s. At congressional hearings in 1959, the agency projected reconstructing 987 miles of timber roads and constructing 7,021 miles of timber roads, plus reconstructing and constructing another 179 miles of roads for other purposes (Baker et al. 1993:247).

The National Park Service built the highway from Apgar down Camas Creek to the North Fork Road in Glacier National Park in 1964. A major bridge was built across the North Fork of the Flathead River just downstream from the mouth of Camas Creek. Prior to the construction of this road, and partly in response to the proposed Glacier View Dam, the National Park Service pushed for the construction of a "loop road" that would connect West Glacier with the road to Waterton Lake via the North Fork (Burnell 1980:3; Bolle 1959:210). The loop road to Waterton Lake was never constructed to highway standards.

The technological advance that permitted the wide-scale construction of roads on national forests was the development of crawler tractors with angled blades (now known as bulldozers). During the 1920s, Forest Service challenges provided much of the initial impetus for the development of the bulldozer. Forest Service engineers conceived the idea and worked in collaboration with industry to develop the first practical bulldozer to replace the horse-drawn plow, Martin ditcher, and grader. Region One helped with the design and financing, and the new "trail builders" were tested in the northern Rockies in 1929. Major manufacturers did not produce bulldozer blades until after World War II; before then they were supplied by independent companies as separate attachments for the major brands of tractors (see Figure 57) (Young 1987:122; USDA FS "History of Engineering":25, 322, 324; Pyne 1982:43).

|

| Figure 57. Bulldozer clearing brush and pushing dirt and boulder, Martin Creek access road, 1946 (photo by K. D. Swan, courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Region One, Missoula). |

Important features of bulldozers were the hydraulic-powered raising and lowering of the dozer blade (replacing the cable lift) and the setting of the blade at an angle for side casting of excavated material. The Forest Service contracted for 11 of these trail builders in 1930; the agency used them primarily for building trails. The impact of the bulldozer-equipped tractor on the logging industry was profound in the 1930s (Young 1987:129-131).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/flathead/history/chap7.htm Last Updated: 18-Jan-2010 |