|

Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960 |

|

FOREST SERVICE ADMINISTRATION, 1905-1960

Introduction

Soon after its establishment in 1905, the Forest Service achieved a reputation for bureaucratic efficiency and extraordinary esprit de corps. This was due to the relative youth of most of the field personnel, the personal dynamism of Gifford Pinchot, and the emphasis on decentralized authority (Caywood et al. 199 1:22). The daily work of pre-World War II forest rangers on the Flathead National Forest varied greatly, but almost all spent most of their time in the field. Besides managing timber sales, fighting forest fires, building trails, and issuing grazing permits, Flathead employees established administrative sites in the backcountry, issued special-use permits, sent foresters to join forest regiments in both World War I and World War II, negotiated complicated land exchanges, and participated in the planning of access roads and timber salvage related to the new Hungry Horse Dam.

As administrative needs changed, some of the land on the Flathead and Blackfeet National Forests was transferred to other Forests, primarily the Kootenai to the west and the Lewis & Clark to the east. In 1910 the designation of Glacier National Park removed a large amount of land from Forest Service jurisdiction.

The creation of the Bob Marshall Wilderness in 1940 has done much to preserve the administrative buildings - and way of life - of the Flathead National Forest of the 1930s era. The historic Big Prairie Ranger Station complex is an evocative, living reminder of a way of life that has vanished on most other national forests. Supplies are still brought in by pack strings, about 40 miles of the old telephone system is still in use, and workers still wield crosscut saws and other non-motorized tools within the Wilderness. The major change is the almost complete dismantling of the extensive fire lookout network that once had such an important role to play. The Spotted Bear Ranger Station, also in the South Fork but accessible by road, has several well-maintained historic buildings at its complex, plus a number of artifacts relating to the Forest's history on display for visitors.

Qualifications of Early Forest Service Workers

The Forest Service's 1907 Use Book described the requirements for being hired as forest rangers as follows:

[Forest rangers] must thoroughly know the country, its conditions, and its people...The Ranger must be able to take care of himself and his horses under very trying conditions; build trails and cabins; ride all day and all night; pack, shoot, and fight fire without losing his head. He must know a good deal about the timber of the country and how to estimate it; he must be familiar with lumbering and the sawmill business, the handling of live stock, mining, and the land laws. All this requires a very vigorous constitution...It is not a job for those seeking health or light outdoor work (Pinchot 1907:33).

In short, as Gifford Pinchot himself said, forest rangers needed to combine the skills of a naturalist with those of a business man (Steen 1976:83).

Because of western resistance to the new land use policies enforced by the Forest Service, the Transfer Act of 1905 (which changed the administration of the forest reserves from GLO control to the Forest Service) required administrators to hire local men whenever possible. In 1905 inspector Elers Koch conducted three ranger examinations in the region. These tests included two days of field events and a one-day written exam. The field exam covered rifle and pistol shooting at a target, riding a horse, putting on a pack, compass surveying and pacing, use of an axe, and cruising a block of timber. The last field exam in Missoula took place in the spring of 1910 (Caywood et al. 1991:18; USDA FS "Early Days" 1944:109-110).

The badge and uniform served as outward symbols of forest rangers' authority. When the Forest Service was created in 1905, Gifford Pinchot organized a contest among Washington Office employees to create a unique Forest Service badge to replace the nickel one worn during the GLO period of administration. The resulting tree emblem came from this contest, and the shield shape was thought to convey a sense of authority. The original solid-bronze badge was reduced to half its size in 1915. The Forest Service introduced a uniform for its workers in 1906; the style, color, and materials have varied greatly over the years, alternating between a quasi-military and a quasi-civilian appearance. For a long time, most field workers wore whatever they found most comfortable (generally blue jeans). No uniform allowance was provided until 1955. In 1934, according to new regulations, Region One permanent personnel had to wear the Forest Service dress uniform, even in the field (although forest guards could eliminate the standard coat). Permanent employees could wear work clothes (of similar color and design) only when the work would cause their clothes to become badly soiled within a short period or if they had no contact with the public. No "off-shape or off-color hats, shirts, or ties" were allowed (Harmon 1980:188, 190-191, 194; Silcox 1935:3-4).

Early Forest Service salaries were generally low compared to similar government work. in the early 1920s, according to inspectors, the Flathead National Forest was paying less than other Forests, with the result that:

less than half the guards are experienced, self-reliant woodsmen. Too great a number may be described as 'kids' - that is young fellows whose age and lack of experience has not fitted them for the pioneer work required of them. Some of them are absolutely useless; they can't chop, can't cook, can't start out alone and get to a fire (Flathead 1920-23 Inspection Reports, RG 95, FRC)

This problem apparently persisted on the Flathead. In 1937, an inspector reported that some of the young men working on a trail crew were "pool-hall punks from Kalispell" (Inspection Reports, Region One, 1937-, RG 95, FRC). The inspectors recommended revising the salary schedule so that the Forest could hire two good men rather than three poor ones.

Daily Work of Early Forest Service Employees

The jobs of early rangers and forest guards were varied. Most personnel, especially those on the local level, helped in all aspects of forest management. When the forest reserves were transferred in 1905, Pinchot gave highest priority to boundary surveys (adjusting existing reserves and examining proposed reserves). Major programs involved protecting the forests from fire, insects, and disease; inventorying the timber; posting boundary and fire notices; reseeding or replanting timber already cut; and managing grazing resources. On the Flathead, those employees who were proficient surveyors worked all over the Forest surveying administrative and homestead sites. They also constructed buildings, corrals, trails, and roads as needed (Steen 1976:84; "Miscellaneous Work 1905" pressbook FNF CR).

As had been the case under the GLO, the early Forest Service expected much of its employees but gave little support in the field. The men were expected to be self-reliant and thoroughly capable. In November 1905, for example, Forest Supervisor A. M. Bliss wrote to deputy ranger John Sullivan:

Get your supplies in for the winter to some point to which you can most readily reach all points along the South Fork Valley. Will trust to your judgment. You will find a store at Bear Creek. / Burn all the brush you can. Go to Columbia Falls the last of December for mail and further instructions. / Prepare yourself for snowshoeing ("Misc Work 1905" pressbook, FNF CR).

Rangers also patrolled to prevent trespass of various sorts, from timber trespass to poaching to the illegal use of Forest Service buildings. For example, in 1915 forest guard Charles Emmons found that someone (probably trappers) had lived in the Lake Roger Ranger Station cabin for several weeks and had stolen cooking utensils and tin dishes. He reported, "The cabin was left in a condition of filth almost beyond description" (FNF Lands).

The tasks in the early years were primarily custodial, and much energy was put into developing the transportation network. Most of the field work was done in the name of "presuppression," including mapmaking and developing communication systems, roads, and trails. The ranger's year was divided into fire season and non-fire season. Rangers and summer guards were spread thin over the backcountry. For example, in 1907 each Lewis & Clark National Forest ranger district covered about 600,000 acres, and each ranger had about five guards working for him during the summer. More specialists' jobs were created in the 1920s (Clack 1923a:7).

The Forest Service hired relatively few office workers during the early years. In 1905 Supervisor Page S. Bunker asked for a clerk to remain in the office during his absence and noted that he would prefer a man who could use a typewriter. As the work load increased, so did the number of employees, both in the office and in the field. In 1905, each forest reserve averaged about 8 employees, including clerks and stenographers. By 1939, the Flathead National Forest employed 19 year-round and 200 seasonal employees. This had increased dramatically to 121 year-round employees by 1964 (Shaw 1967:2, 5; Winters 1950:9).

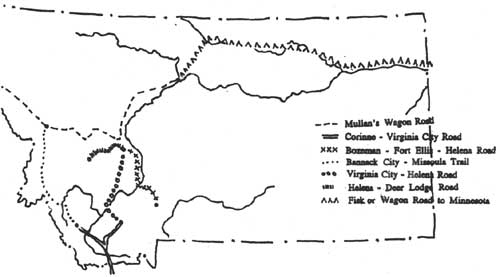

The ranger districts on the various forest reserves/national forests modified their boundaries frequently. For example, in 1898 the Flathead Forest Reserve was divided into two districts, but by 1900 it had been divided into 24 ranger districts. Soon after this the number of districts was greatly reduced. Beginning in the 1920s, the ranger districts in Region One were steadily enlarged due to improved transportation and communication facilities (see Figure 22) (J. B. Collins to GLO Commissioner, 10 May, 1900, entry 44, box 3, RG 95, NA; Caywood et al. 1991:42, 46, 49).

|

| Figure 22. Flathead and Blackfeet National Forest ranger districts ca. 1954. Earlier ranger districts were much smaller. (click on image for a PDF version) |

In 1908 Pinchot established field headquarters in six Districts (now called Regions), one of which was in Missoula. Previously, the nation's Forests had been divided into three Districts. The Forest Service used inspections by men from the Washington or regional offices to assist officers in their duties. These inspections were very detailed. For example, an inspector who visited Hemlock Lookout in 1937 "stressed the importance of having more system in the filing of his food supplies in the cupboards" (Steen 1976:77, 80; Inspection Reports, Region One, 1937-, RG 95, FRC).

In 1905 the Forest Service issued a pocket-sized Use Book, with a brief summary of Forest regulations, for field personnel and the general public. Not all employees read this manual promptly upon being hired. Jack Clack, hired to work on the Lewis & Clarke National Forest in 1907, met Gifford Pinchot there. Pinchot asked if he had read his book of instructions, and Clack replied honestly, "Hell, no. I haven't received any mail for three months" (Caywood et al. 1991:22; Bloom 1933:3).

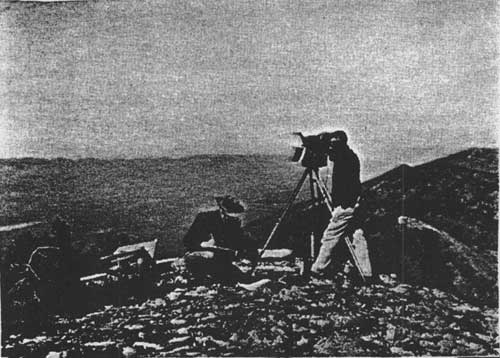

Time spent in the office was minimal in the early years. According to Flathead National Forest retiree Pat Taylor, "The Ranger would only get a thin manilla envelope a week from the S. O. He would usually stay in Saturday afternoons or perhaps all day to do his office work. The rest of the time he was in the field" (see Figure 23). Some of the work kept the ranger station operating smoothly. For example, in 1924 Ralph Thayer spent one day in September at Moran Ranger Station splitting wood, cleaning the barn and root house, picking up tools, and washing dishes (Taylor 1981; Thayer 1924).

|

| Figure 23. Cartoon drawn in 1930 by Viggo Christensen, a Montana Forest Service employee (from Randall 1967:28). |

In the early 1920s a number of Flathead National Forest employees undertook an inventory of three "activities" on the forest: silviculture, grazing, and fire. The men carried their supplies and tools on backpacks, making maps as they went. Frank Liebig described these as follows:

It is a man's job all right, and he has to have an eagle eye, climb like a billy goat, swim like a fish, and run over the windfalls like a squirrel, but, 'Oh, joy,' when you do hit the headwaters and climb the mountains peaks, what a wonderful scenery a man can get" (Liebig 1924:8).

Liebig and others covered 1,001 acres per man-day on the Middle Fork survey, and he casually mentioned that the work was done on contributed time, available because the fire season was easy (Liebig 1924:9).

Forest ranger Clyde Fickes described how he traveled on the Lewis & Clark National Forest in 1908. He rode a saddle horse followed by a packhorse on a lead rope with canvas pack bags. His load of 180 pounds included two frying pans, three tin plates, a coffee pot, table knives, forks, spoons, a hunting knife, an ax, a shovel, a cross-cut saw, a rifle, a camp bed, clothing, a rain slicker, and food. He spent about half his time traveling in this manner, cutting logs out of the trail as he went. When he arrived at his destination he would unsaddle the horses and turn them out to graze. He would then collect dry wood, get a fire started, pitch his 7'x 9' tent, and spread his bedroll over fir boughs. After eating, he would wash the dishes, smoke a pipe or cigarette, check the horses, and tie them up for the night (Fickes 1973:32-33).

Clyde Fickes started his Forest Service career on the Lewis & Clark National Forest. In 1907 he was appointed forest guard at a salary of $720 per year. His early work was to survey and plat administrative site withdrawals and homestead claims. Near Swan Lake he met ranger Jack Clack (see Figure 24) (Fickes 1973:3, 5, 7). He described Clack as follows:

He was a tall, well-built man, brown as an Indian, sitting on a long-legged bay horse and leading a packhorse. Bareheaded, his hat on the saddle horn, he ran his hand back over his bald head; it came away covered with mosquitos and blood, which he nonchalantly shook off as he greeted us" (Fickes 1973:7).

|

| Figure 24. Jack Clack wearing the packframe that he designed (from Swan 1968). |

Not all Forest Service workers enjoyed being alone in the field so much of the time, especially those who had girlfriends in town. One seasonal employee wrote in his diary of August 1908:

Gosh but I am lonesome wish I had someone to talk to have made up my mind that I don't want to be alone much in the mountains. I am going to Java tomorrow where I can talk to the miners and Japs. I am still thinking of Mary (28 August 1908, FNF employee log, FNF CR)

By the 1930s the Forest Service had developed three types of backcountry camps for employees: permanent, such as guard stations; tent camps; and the more temporary "gypsy camps." Tent camps were usually 6-10 miles apart and located at trail intersections with a good water supply.

Most of the field workers were in their 20s, and although whiskey was available (despite Prohibition), the low wages controlled the drinking. According to Pat Taylor, "Among the crews there was lots of joking, bantering and good natured practical jokes." Evening conversation, he recalled, generally revolved around the merits of various boots and guns (Taylor 1986; Taylor 1988).

At a typical trail crew camp, the person assigned to be cook would get up an hour early to build a fire in the wood stove and make the coffee. He would carry in buckets of water from the creek and whittle shavings if he had not done so the night before. Unless they were on a fire, men on backcountry crews worked six days and spent Sundays washing clothes. The men were on call 24 hours a day. No one went to town from June 15 until September unless there was an emergency (defined as a death in the family or a toothache). Pat Taylor commented, "I have known some fellows who got off to attend funerals of 6 or 8 grandmothers" (Taylor 1981).

Generally the members of a small backcountry crew would take turns cooking. "It was understood that no one would complain unless he wanted to take over the cooking job," remembered Pat Taylor. If a crew member was a terrible cook, he would haul wood and water and wash dishes instead. Employees were expected to sweep and mop the cabins in which they stayed, in addition to shaving once or twice a week. "It was said that to qualify for a Ranger's job, one must shave every day and be able to spell 'approximately.'" There was an unwritten law that firewood and kindling and a full gas lantern should be left in camps for the next occupant. Employees would work late to finish a job or leave early if done. On cruising or scaling jobs, evening work was done voluntarily to compile cruise notes or to add scale book volumes. No overtime was paid in the 1930s; wages remained the same even if one was on a fire more than 100 hours in one week. In the 1930s seasonal employees took home $77 a month for a standard work week of 44 hours (five 8-hour days plus Saturday mornings). As a small benefit, seasonal employees were usually allowed to use a Forest Service cabin as headquarters for winter trapping (USDA FS "Early Days" 1976:109; Taylor 1988; Taylor 1981; Owens 1989).

Backcountry crews were also hosts to the public. When anyone rode or walked into camp, the first rule was to inquire if they had eaten and to offer visitors a cup of coffee. The Forest Service employees stayed up until the visitors and their horses were settled (Worf 1989).

The commissary clerk (later known as the dispatcher) answered the phone, cooked for the station, kept employees' work records, and dispatched men to fires. He also ordered the weekly supplies, mowed lawns, took weather measurements, issued gasoline, and did the paper work on timber sales. In 1931 the cook at Tally Lake was required to prepare breakfast and supper for the workers and in between to hike up a steep 3-1/2—mile trail with a fire pack and look for fires until it was time to cook supper. "In a short time he quit and we 'batched' for several years," recalled Pat Taylor (Taylor 1981; Taylor 1986).

Forest Service Food

In the early years of the Forest Service, employees provided their own food (generally game supplemented with supplies they packed in for themselves). The Forest Service did not supply its employees with food and bedding until 1917. As packers were hired to supply remote ranger stations, employees had to rely on the food brought in by the government or fish and meat that they procured for themselves while in the field (USDA FS "Early Days" 1944:217).

As late as the 1930s some of the backcountry Forest Service food was left over from World War I military rations. These included 5-pound cans of lunch meat "stacked like cordwood" which no one would eat after their first try. Another was evaporated eggs, also unpopular. Other food regularly used in 1930 on the Blackfeet National Forest included smoked ham and slabs of bacon, canned roast beef and salmon, condensed evaporated milk, lard and butter in cans, canned apples and dried fruit, beans, rice, macaroni, corn meal, rolled oats, and tapioca ("To my knowledge no tapioca was ever cooked," commented Pat Taylor). There was no fresh bread, so biscuits known as "Dough Gods" took its place. Pancakes were made from sourdough; the starter was carefully maintained all summer and protected in the mule packs (Taylor 1986; Taylor 1981).

After the coming of the CCCs, Forest Service food improved greatly because the agency learned by observing how the Army supplied food. Fresh meat began to be supplied to permanent camps and fresh bread to all crews. Canned peaches, pears, apricots, pineapple, grapefruit, and even strawberry jam made their appearance (Taylor 1986).

In 1939, typical food for a trail crew included a breakfast of hotcakes with canned ham or bacon, a lunch of a small can of fruit and sandwiches made with baking powder biscuits (carried in a sugar sack tied to the back of the worker's belt), and a supper of baking powder biscuits, canned ham or tin willy (or canned stew), spuds, and a canned vegetable followed by canned fruit. Trail crew workers supplemented their diets with fish caught from nearby streams (USDA FS "Early Days" 1976:110; Montgomery 1982).

Winter Work

Timber cruisers inventorying the forest's timber resources routinely worked in the winters, sometimes in deep snow. R. L. Woesner worked on a timber sale in what is now Glacier National Park some time between 1905 and 1910: "When we left the cabin we always set up a pole in order to be sure to find it when we returned, as we often had to dig down in the snow to find the cabin" (USDA FS "Early Days" 1944:21).

During the winters of the 1920s through the 1940s, the rangers worked out of the Federal Building in Kalispell (247 1st Avenue East). When in the field, they marked timber sales, put up ice, and did game counts and snow surveys. Much of their work was accomplished on snowshoes (see Figure 25). When possible, crews of rangers and a few key men would be transported to the job site in cars; if not they used a toboggan and later snow cats (the first snow cat was introduced in 1951 (Taylor 1981; Baker et al. 1993:180).

|

| Figure 25. Winter camp near Calbick Creek, winter game studies, 1936. When cabins were unavailable, workers stayed in tents (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

Snow surveys were designed to measure winter snowpack and to forecast spring runoff. They were tried to a limited extent in Montana between 1918 and 1935, then expanded with federal assistance. In 1935 the Corps of Engineers installed 15 snow courses along the Continental Divide, and in the early 1940s more courses were added in the Columbia and Missouri River basins. The earliest snow courses reported in the Flathead National Forest area were established in 1937 on the Flathead River, Logan Creek, and Desert Mountain. Snow surveys were done by one man alone until 1943 or 1944, when two men were sent out together for added safety (Taylor 1981; Monson 1961:5-6, 26).

Pat Taylor described doing snow surveys on the Tally Lake Ranger District, which had three snow courses. He carried a light canvas bag with one shoulder strap that weighed about 10 lbs. It generally took him five days to travel slightly over 90 miles. He commented, "Under good traveling conditions the trips were not too tough. Otherwise they were man killers. I would hit the trail at 5 AM to take advantage of the best snow conditions. Sometimes it was after dark before returning to camp" (Taylor 1988).

The Forest Service cooperated with Glacier National Park on occasion. One example was a timber survey of the area burned on national park and forest lands by the 1929 Half Moon fire, done during the winter on snowshoes ("Another Emergency Job" 1930:4).

Families

Many rangers living in remote areas had their wives and children with them. For the children, this could be an idyllic life, as they often were allowed to accompany their father on his rounds. Tally Lake ranger Paul Redlingshafer, for example, took his children with him in the early 1920s on trail trips; each child had his own horse to ride (Redlingshafer 1988).

The wives of Forest Service rangers often assisted their husbands for no pay. They helped with a great variety of jobs, including dispatching, surveying, fire fighting, cooking for crews, meeting the public, taking care of office duties, tending the stock, and marking timber stands for sale.

For example, Mary and Ed Thompson were married in 1909 and were stationed at the Echo Ranger Station until he retired in the 1930s. At first they lived in a small cabin in the woods that had been built by a homesteader, but later they added a large log house, barn, blacksmith shop, bunkhouse, outhouse, and other outbuildings (see Figure 26). Mary, like many rangers' wives, raised a vegetable garden, chickens, and pigs and kept a Jersey cow for milk and cream. She served as ranger alternate without pay when her husband was absent. The family shopped in Kalispell, 26 miles away, but in the winter the only way out was by horse-drawn sled. They provided meals to anyone who came to work or visit, and their nearest neighbors (and their mail box) were six miles away (Glazebrook 1980:18-19; 24FH110, FNF CR; Hornby 1932:6-7).

|

| Figure 26. Echo Ranger Station, 1924 (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

Some forest rangers met their future wives as a result of their duties in the woods. For example, Ray Trueman, ranger at Big Prairie, eventually married a woman named Ruby Kirchbalm who operated a 30-horse pack string between Coram and Big Prairie after World War I (USDA FS "Early Days" 1962:17; Shaw 1967:27-28).

Injuries

Flathead National Forest rangers and forest guards and other employees have always done much of their work alone in the field in sometimes dangerous situations. Not surprisingly, some have died on the job. The causes of death have included railroad accidents, dynamite blasts, lightning, automobile accidents, heart attacks, falling trees and logs, plane crashes, and even exhaustion from running during a fire. In 1924 the daughter of a man looking after stock wintering at Big Prairie on the South Fork became ill. She died and was buried there before her father was able to snowshoe to Missoula and back for medicine (Shaw 1967:62, 98-99).

In 1930 a smokechaser on Nasukoin Mountain in the North Fork was mauled by a grizzly. In 1928 Ralph Thayer was mauled while locating a trail, also in the North Fork. Both lived to tell their stories (Shaw 1967:117; Yenne 1983:52).

Special-Use Permits

Special-use permits were issued on the Flathead National Forest for such diverse activities as cutting wild hay, growing a garden and flowers along the Middle Fork, building hunting cabins, establishing logging camps, running a commercial packing business, and building summer homes on various lakes (Holland Lake, Lake McDonald, Swan Lake, and others). Dude ranches were also operated under special-use permits. For example, the Diamond R Ranch at Spotted Bear was started in 1927 by Guy Clatterbuck, who had been located the previous year at Spotted Bear Lake. Private hotels were also under special-use permit, such as the Belton Chalet in West Glacier (the Glacier Park Hotel Company was issued a permit for this hotel in 1914) (Opalka 1983; FNF "General Report" 1918)

One spectacular summer home was the Rock House, built in 1930 through a special-use permit on the west shore of Swan Lake for the L. O. Evans family (Evans was president of the board of ACM for a time). In 1937, a forest inspector commented that the management situation at Swan Lake was different from many places because most of the land around the lake was privately owned. He added that wealthy people had moved in over 25 years ago seeking privacy and had "pretty much dominated Swan Lake for 25 years." The ranger tried to protect the public's interest in recreation in the area and at the same time avoid appearing "bureaucratic or spiteful and so retain the good will and cooperation of private owners" ("Rock House" 1984; 18 December 1937 memo, Inspection Reports, Region One, 1937-, RG 95, FRC).

In 1930 the Flathead National Forest maintained 13 residential permits in Essex, which had a population of 200 at the time, of which 90% were railroad employees. In Belton and Essex many of the homes, and the school, were built on federal land under permit (W. I. White, 1/28/30 "Report on Municipal Watershed," 2510 Surveys, Watershed Analyses, 1927-29, RO; Shaw 1967:28).

Forestry Research and Education

The Department of Agriculture offered technical aid and advice to private landowners since 1898. In 1924 Congress passed the Clarke-McNary Act, which among other things provided for federal funds to match state and private funds in supporting cooperative fire protection, distribution of seedlings for reforestation, and other programs. The act also broadened the authorization for the purchase of forest land to permit the government to acquire land for national forests regardless of whether or not it was located on watersheds of navigable rivers. Research in forestry greatly expanded after 1905. The first forest experiment station was established in 1908 in Arizona. The Forest Products Laboratory was established in Madison, Wisconsin, in 1910, and a research branch was created within the Forest Service in 1915 (Gates 1968:595, 597; Winters 1950:14; Randall 1967:62). Forestry education also was becoming more widely available; the Montana State University School of Forestry was established in 1913.

By the early 1920s the Forest Service was encouraging its employees to become involved in public relations and educational efforts. In 1921, for example, the Blackfeet National Forest publicized its work and philosophy through articles in local newspapers, talks to school groups and Boy Scouts, signs and posters in local businesses, and window displays. In 1926, Frank Liebig set up a large display in a big show window of the Kalispell Mercantile that featured all the different kinds of fungi that grow in the forest, plus a variety of fire signs. Another display showed a slice from a Douglas-fir tree that was almost 450 years old, with cards marking the years of historic events, including large fires in the area (Northern District Bulletin 5 (May 1921): 34; Liebig, "Flathead Fungi" and "An Historian" 1926: 13, 14).

World Wars

The Forest Service contributed to the World War I war effort in various fields, including those of national defense, military intelligence, and the wood products industry. The mobilization of the war industries led to larger timber harvests and increased road development in Region One, and the prices of labor and construction materials rose. The Forest Service organized and equipped a forestry regiment in the Army Corps of Engineers that was sent to France to log and mill behind the front. Many Flathead Valley residents joined this regiment. During World War I, because the wages in private industry were so high, many Forest Service employees left their jobs to earn more money elsewhere. A few women worked as lookouts during World War I because of labor shortages (Caywood et al. 1991:33-34; Cusick 1981; James 1990:8-9).

Key individuals in the Forest Service were removed to serve in the military during World War II. The total budget of the Forest Service was cut nearly in half in 1943 and 1944 because of the war and because so much money went into the rubber tree plantations in California, part of the Forest Service war effort. The Forest Service faced a manpower shortage as CCC camps were phased out in 1942 and as employees joined the armed forces. In Region One, all road and trail development was stopped except where the government wanted access to strategic metals such as chrome and tungsten. Quite a few lookouts were no longer manned, and the Forest Service hired women to be stationed at some of the others and high school students to work in firefighting, blister rust control, and slash disposal. Before World War II, only 13 women had been hired as professional foresters, and the CCC did not include women in its program (Gray 1982:187; Caywood et al. 1991:60; Baker et al. 1993:160; James 1990:8-9).

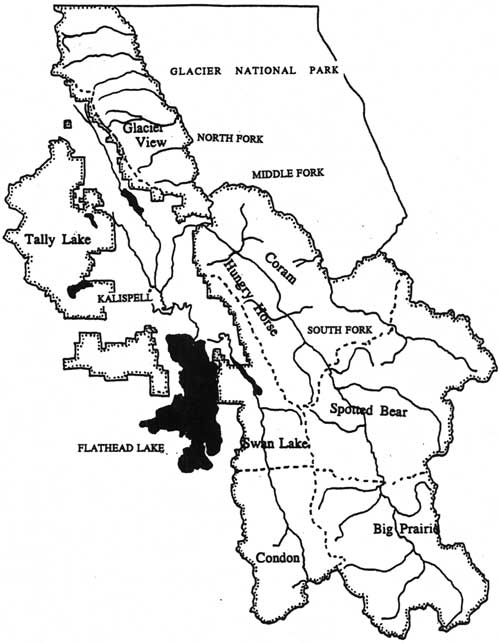

After World War II had focused attention on Forest Service mapping and surveying abilities, the Forest Service was designated one of the standard mapping agencies of the Government. The agency received increased funding and training to produce topographic maps for standard coverage of the United States (see Figure 27) (USDA FS "History of Engineering" 1990:7, 445).

|

| Figure 27. Flathead National Forest surveys, 1960. Fred Kyle, cartographic aid, calls out readings he has obtained from tellurometer. William Markham, cartographic aid, records in notebook (photo by Peyton Moncure, courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Region One, Missoula). |

Administrative Sites

Early forest rangers under the GLO either rented buildings or used their own homes as ranger stations. There was no funding in the early years for constructing any administrative buildings in the woods. Soon modest amounts of money were allocated for building and maintaining Forest Service "administrative sites." According to an inspection report, in the year 1906 more cabins and pastures were built and fenced on the Lewis & Clark forest reserve than in all previous years combined (1898-1905). The cabins built then averaged 17' x 26' and generally cost $200-350 for labor and $50-75 for materials. All were supplied with a light-weight sheet steel stove (Ise 1920:261; 28 November 1906, "Reports of the Section of Inspection," entry 7, box 4, RG 95, NA).

In 1912 an amendment was passed forbidding the use of homesteaders' cabins as ranger stations. After funds became available, the number of buildings constructed for various purposes on the national forests grew rapidly. In 1939, there were 147 lookout buildings and 247 other buildings on the Flathead National Forest (Figure 28) (Ise 1920:261; FNF, "Informational Report" 1939).

The Forest Service began to "withdraw" plots of land for actual or potential administrative sites soon after the Forest Homestead Act was passed in 1906. The men selecting the sites tried to choose locations that were generally spaced about a one-day's horse ride apart. These withdrawals protected the land from being claimed by a homesteader, a real consideration since the qualities that made a site attractive to a homesteader - water, available pasture, relatively flat land - were also necessary for guard and ranger stations. The sites could not conflict with prior mineral or homesteading claims. Many withdrawals were made before the land had been formally classified; later some of these were once again made available to homesteaders.

Between 1898 and 1918, forest rangers and guards designed and built most of the permanent improvements in the national forests. Because the ranger drew up the plans, these buildings often resembled homestead cabins of the same period. Sometimes their building or re-building attempts were not very successful. In 1922, for example, the regional forest inspector commented that "Buildings on the Blackfeet are surely a worthless lot of shacks." A 1914 act limited the cost of any building for Forest Service use to $650 without special congressional authority. Flathead National Forest supervisor Page Bunker recommended as early as 1910 that standard types of buildings be adopted for each Forest, but a Region-wide standardized planning effort was not to come until the 1930s (Caywood et al. 1991:67, 69; Flathead 1920-23 Inspection Reports, RG 95, FRC; Kinney 1917:251; "Report of Supervisors' meeting, 3/21-26/1910, 1360 Meetings - Historical - Early Supervisor Meetings, RO:47).

Some of the early ranger stations, and the year of construction of the first building on the site, are listed below. A number were originally the residences of rangers; others were the cabins of homesteaders, prospectors, etc., that the rangers used for a time as headquarters. Most of these early ranger stations were later abandoned or demolished in favor of better locations as the needs of the Forest Service changed (see Figure 29). Some are no longer within the boundaries of the Flathead National Forest since the sites are now in Glacier National Park or the Kootenai National Forest.

1899 head of Swan Lake 1902 Cedar Creek near foot of Lake McDonald 1902 Coram 1904 Big Prairie 1905 Hahn Creek 1905 Riverside (South Fork) 1906 Black Bear (burned in 1910) 1906 Spotted Bear Lake 1906 Danaher 1908 Star Meadow 1908 Swan Lake 1908 Tally Lake 1909 Bear Dance 1909 Holland Lake 1909 Hungry Horse 1910 Belton 1910 Three Forks (Shaw 1967:7, 49; FNF "General Report" 1918; Wolff 1980:53; site files, FNF CR; Blake 1936:1; Mitchell 1973).

|

| Figure 29. Big Prairie Banger Station, 1913. This cabin was located closer to the South Fork of the Flathead than the current administrative complex (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

Many administrative sites that were withdrawn were never actually used for anything more permanent than as summer camping and pasture grounds for forest employees passing through the area. These were strategically located at trail junctions with sources of water and good pasture. Some were withheld specifically to prevent speculation by private parties, such as the River Side Administrative Site selected in 1912, located about 10-12 miles above Henshaw Ford at "the most natural crossing on the North Fork" (FNF "General Report" 1918).

An administrative site was withdrawn in the Belton (West Glacier) area partly in order to "bring the greatest competition against the monopoly of the Belton Mercantile Company," which owned all the land within 1/4 mile of the railroad depot except for the Forest Service site. A seasonal employee lived in a house hidden behind a steep hill because the Forest Service felt the agency did not have enough funding to build a station along the road "that would conform in architecture to the Great Northern Chalets" and that the traffic on the road (which did not yet go over Marias Pass) did not warrant such an expense (FNF "General Report" 1918).

The Coram Bridge Station, located at the village of Coram along the railroad tracks, was withdrawn as a banking ground for timber. In 1913 a cabin and storehouse were built to store government supplies loaded at that site. The Forest Service also administered special-use permits at this location in the 1910s for three stores, a barber shop, and a residence (FNF "General Report" 1918). South of Coram, along the South Fork, was the Elk Park administrative site, also known as the "Elk Park packers' camp" (see Figure 30).

|

| Figure 30. Elk Park packers' camp on the South Fork, 1924 (the site was flooded by the creation of the Hungry Horse Reservoir). The log building, wall tents, pack stock, and location near water are typical of Flathead National Forest administrative sites (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

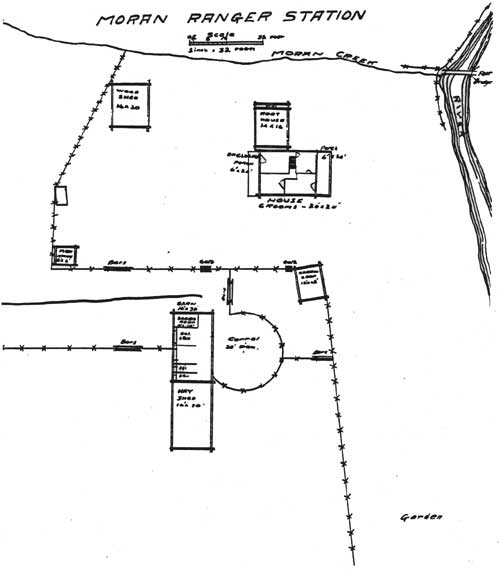

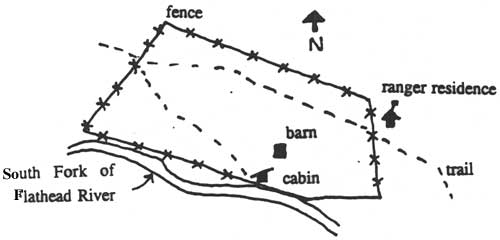

Initially, the Use Books required that Forest Service cabins be built of logs whenever possible, with shingle or shake roofs. In the early 1900s the authority for planning construction on the Forests shifted from the inspectors to the Forest, with the Regional Office playing an oversight and technical advisory role. Clyde Fickes of the Regional Office recommended that in choosing a location for a building site, the following factors should be considered: sunlight, drainage, background, fuel, pasture, and water supply (see Figure 31) (Caywood et al. 1991:26-27; Fickes 1935).

|

| Figure 31. Drawing of Moran Ranger Station, ca. 1918. Notes accompanying the map indicate that the house and barn were built of logs. The log chicken coop was originally a trapper's cabin built in 1890. The compound was enclosed with 1-3/4 miles of buck and rail fence. The river shown to the east of the compound is the North Fork of the Flathead. This ranger station was discontinued and the buildings subsequently destroyed (from FNF "General Report" 1918). |

From 1918 until 1928 the Forest Supervisor usually reviewed the building's design and placement. The architectural style continued to be similar to that of local vernacular buildings. In the 1920s and 1930s, buildings that were near supply points generally were built in the bungalow style with Craftsman features such as exposed rafter tails, dormers, and roof brackets. These were of Forest Service design or followed a generally available pattern-book plan. In general, Forest Service buildings were utilitarian, "rustic" in appearance, and reflected local designs and materials (Caywood et al. 1991:73, 95).

Clyde Fickes of the Regional Office prepared a handbook in 1935 giving plans and instructions for standard Forest Service buildings and structures. He personally preferred "chopper cut" (irregular) log ends; he felt this end finish imitated early log construction techniques. This style is not present on earlier Forest Service log buildings but is found often on buildings dating from the 1930s and later (Caywood et al. 1991:99).

The Forest Service took great pride in its buildings, even in details such as paint trim. In the 1930s the agency increasingly encouraged uniformity in its buildings, and by the mid-1930s standardized plans were provided for virtually every building project in the region. Natural settings and native materials were preferred, such as log, wood shakes, and native stone (Caywood et al. 1991:55-56, 66).

Log construction of Forest Service administrative buildings was typical in the more remote areas. The "Rocky Mountain" style log cabin is the style common to many Flathead National Forest backcountry pre-World War II buildings, and it was predominant throughout Region One. This style of log cabin features an off-center door in the front wall, an extended porch gable that forms a sleeping loft, and compound dovetail notches. Flathead National Forest buildings with this standardized Region One plan include Basin, Gooseberry Park, Pentagon, Shaw Station, Hahn, Challenge, and Ninko Cabins. Most of the buildings of this style in Region One date from 1928-34, but some on the Flathead are later (Wilson, Mary 1984:1, 34; Caywood et al. 1991:74, 77-79).

Some of the early Flathead National Forest employees were extremely skilled in log construction. One of these was Vic Holmlund, who immigrated to the United States from Sweden in 1875. He came to the Flathead Valley with a Great Northern Railway construction crew as a "tie hack" (hewer of railroad ties). "Big Vie" (he was almost 6' 6" tall) was a master at hand hewing logs and creating compound dovetail notched corners. He worked the summers of 1924-27 and 1929-34 for the Flathead National Forest building fire lookouts and ranger stations. Another skilled hewer of compound dovetail notching was Everett M. Hart, who worked for the Forest Service from 1913-26, sometimes with Big Vic (see Figure 32). The log construction technique of "scribing" was introduced in the late 1920s. This technique could be taught relatively easily to inexperienced builders and produced tight-fitting ventral saddle notches. Earlier buildings generally had square, V, double saddle, or dovetail notches (Green 1969:1, 15-17; personnel files, FNF CR; 24FH20, 24FH428, FNF CR; Caywood et al. 1991:78, 82).

|

| Figure 32. Garage/blacksmith shop under construction at Spotted Bear Ranger Station, 1925. Master log carpenters Vic Holmlund and Everett Hart probably helped build these buildings, which are currently known as the fire cache and the old office (photo by Everett Hart, courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Kalispell). |

An excellent example of a typical backcountry Forest Service administrative complex is the Big Prairie Work Center (formerly the Big Prairie Ranger Station), located along the South Fork (now within the Bob Marshall Wilderness). In 1937 a forest inspector described Big Prairie as "delightful - so delightful that it cannot be forgotten." At that time the buildings at the complex included a "nice log cabin" ranger dwelling, a combination office/kitchen/dining room and warehouse, a bunkhouse, and a blacksmith shop (see Figures 33 and 34). The Big Prairie airfield was completed in 1931 (27 December 1937 memo, Inspection Reports, Region One, 1937-, RG 95, FRC; "History of the Use of Aircrafts," n.d., FNF CR).

|

| Figure 33. Big Prairie Ranger Station complex, ca. 1917 (FNF "General Report" 1918). |

|

| Figure 34. Big Prairie Ranger Station complex, 1990. This shows the variety of buildings needed at a typical backcountry ranger station (24PW1003, FNF CR). |

In 1918 the Flathead National Forest (south half) had ten ranger districts: Echo, Lower Swan, Upper Swan, Upper South Fork, Spotted Bear, Lower South Fork, Coram, Belton, Essex, and Big River (now called Middle Fork). These varied in size from 46,200 acres (Coram) to 547,800 acres (Upper South Fork). In 1918, Echo, Lower Swan, Coram, Belton, and Essex were year-round ranger stations. The other stations were "chiefly protective" in purpose and so were not manned during the winters. All but two of the stations were connected to the Forest Service phone system; from Belton and Essex the rangers had to use the Western Union telegraph system to get messages in and out. The latter two stations were the only ones at which the ranger and the government did not have horses; the railroad was the main means of transportation instead (FNF "General Report" 1918).

By 1923 Flathead National Forest supplies were coming in from Central Purchase and being checked out to camps. Beginning in approximately 1928, supplies, materials, and equipment were shipped direct from the Spokane Warehouse to the site where they were to be used. The Flathead National Forest in 1938 was one of the few forests that still ordered in bulk, shipped to Kalispell, and then distributed on order to the field rather than having orders shipped directly from Spokane (7 April 1924 memo, Flathead 1920-23 Inspection Reports. RG 95, FRC; 13 September 1938, Flathead Inspection Reports Region On, RG 95, FRC).

The abandonment of isolated sites close to the field and their replacement by centrally located district headquarters is typical of Forest Service development during the 1930s. This centralizing trend depended on the expansion of the Forest Service road system, which improved access to work areas. The administrative sites that are still in use today in the backcountry were generally established after World War I.

In 1905 Flathead National Forest headquarters were moved from Ovando to a room in the Conrad Bank building in Kalispell. When the Federal Building was constructed in Kalispell in 1917, both the Flathead and the Blackfeet National Forests had their supervisor's offices on the second floor (the first floor was devoted to the post office). This building now houses the Flathead County Library and School District 5 offices. Some years additional space was rented in Kalispell. For example, for two winters in the 1930s the engineering crew was located in offices over Jack's Tavern and in the Eagles Hall on 1st Avenue West in Kalispell (Shaw 1967:5; Helseth 1981).

Boundaries

The boundaries of what is now the Flathead National Forest have changed greatly over the years since 1898. When the forest reserve was originally mapped, its boundaries were drawn roughly, tending to follow section lines, because there was not enough funding for ground surveys. The 1898 boundaries were quite different than those of today, extending east of the Rockies but not including much of the area now part of the Tally Lake Ranger District. A few years after the forest reserves were proclaimed in 1897, foresters began surveying and reviewing the lands. As a result, some lands were excluded from the forest reserves because they turned out to be submarginal in timber growth potential or else agricultural in nature (Pinchot 1907:8).

On June 9, 1903, the area bordering the Great Northern Railway along the Middle Fork was added to the Flathead National Forest by presidential proclamation. In 1903 the Flathead and the Lewis & Clarke forest reserves were consolidated into one reserve, the Lewis & Clark, but they were separated again in 1908 and re-named the Blackfeet and the Flathead National Forests (see chart of all the names of the Forest at the end of the Introduction). The Kootenai National Forest was designated in 1906. Four years later, the land in the eastern part of the Blackfeet National Forest was transferred to establish Glacier National Park. The Blackfeet National Forest was then consolidated with the Flathead and the Kootenai National Forests in 1933 (62% of its land was subsequently administered by the Flathead). When the Blackfeet National Forest was combined with the Flathead, making it almost 2.6 million acres, a Forest Service publication commented, "If there is a National Forest area of similar size in the United States, under one Supervisor's jurisdiction, with more deep-downs and higher-ups and more units of inaccessibility, it has never yet been discovered" ("Establishment and Modification" 1973: passim; "Blackfeet Forest Reports" 1934:8).

For several years prior to 1923 the Spotted Bear and White River areas were administered by the Lewis & Clark National Forest, but in 1924 they were turned back to the Flathead. The Island Unit (formerly referred to as the "Floater") was managed by either the Blackfeet National Forest or the Flathead National Forest until 1918, when it was transferred to the Flathead National Forest (15 December 1923, Flathead 1920-23 Inspection Reports, RG 95, FRC; 1918 Presidential Proclamation, 3 June 1918; FNF Lands). All forest reserves around the country were called national forests beginning in 1907, and in that year the spelling of "Clarke" was changed to "Clark."

The General Exchange Act of 1922 gave the Forest Service authority to exchange nonmineral national forest land or timber for private or state-owned lands of equal value within the forest. This act was critical for the consolidation of Forest Service ownership. The basis of the exchange was equal value, not equal area. During the Depression, many companies such as the ACM had large holdings of cutover lands on which they were paying taxes but earning no income. Some donated these lands to the Forest Service, adding to the Forests or to primitive areas. This federal acquisition of cutover timber land was thought to help the lumber industry by stabilizing land ownership and promoting reforestation (Steen 1976:147; W. Robbins 1982:208).

Private landowners within the national forests could essentially sell their land to the Forest Service; under the 1922 act they obtained cash for their land by collecting the revenue earned from Forest Service timber sales elsewhere. The timber sale and the land to be exchanged did not have to be on the same Forest. For example, in 1927 the receipts from a timber sale on the Blackfeet National Forest were used to pay for land that the Kootenai National Forest obtained under the land exchange act (Baker et al. 1993:123; FNF Lands).

Companies based in the Flathead Valley that donated land to the Flathead National Forest via land exchanges included the Empire Lumber Company of Kila and the Brooks-Scanlon Lumber Company of Eureka. In 1939 the F. H. Stoltze Land and Lumber Company donated about 10 acres of land to the Flathead National Forest for the site of the Whitefish Lookout. In 1935 the J. Neils Lumber Company of Libby exchanged over 8,000 acres for timber (cash) (1928 report, Flathead Inspection Reports Region One, 1928 report, RG 95, FRC; FNF Lands).

When Montana became a state in 1889, the Constitution granted it approximately 5,100,000 acres, consisting of sections 16 and 36 in each township. Those sections with timber on them provided the base for the state forest system. By 1916 Montana had a permanent official board of forestry. Since much of the land granted to the State was within national forest boundaries, a trade was arranged whereby the state would receive blocks of commercially valuable national forest land, or public grasslands in eastern Montana, in exchange for state-owned timber lands within national forests (Kinney 1917:217; Burnett 1982:11, 13; Cusick 1986:10).

In 1918 President Wilson conveyed the land for the Stillwater and Swan River state forests to Montana. The land was selected in lieu of unsurveyed school land sections within national forests. In 1925 the Stillwater, Swan River, and Coal Creek state forests were designated and mapped. Reportedly, the state forester had planned a second land exchange to include the Sunday Creek, LaBeau Creek, and Good Creek drainages to increase the acreage of the Stillwater State Forest to approximately 200,000 acres, but after he left office the land exchange was no longer considered (Moon 1991:66; Conrad 1964:29; Cusick 1986: 10).

The large block of private land that still exists within the Stillwater State Forest was reportedly created as a result of a "land steal," revealing the power at the turn of the century of the major lumber companies in the area. Some time before 1907 the State Land Board authorized the sale of nearly 50,000 acres of timberland (averaging 10,000 board feet per acre) that the state had selected in that area. The sale required a large deposit (eliminating small operators), and it went to three large lumber companies for $14 an acre. The deal was reportedly engineered by the Northwestern Lumber Company of Kalispell, and the state lost millions of dollars in the sale (Moon 1991:22-23).

Only rarely did the threat of lawsuits or violence occur in relation to land exchanges, but such an event did take place in Belton in 1909. Section 36, bordering Belton on the south, was claimed by both the state and the Forest Service, the latter because the land had not been surveyed for the state when the forest reserve was created in 1897. In 1909 the state sold 40 acres of the section to the Great Northern Railway as a chalet site. Flathead National Forest supervisor Page Bunker sent ranger Jack Clack and a crew to Belton to fence the area and station a fire guard there as evidence of the federal government's claim to ownership. For one day Clack hastily prepared to defend the 40 acres against the state militia expected to arrive on the Great Northern. The anticipated troops did not arrive, and later a federal court decided in favor of the Forest Service (USDA FS "Early Days" 1944:3-4).

Northern Pacific Railroad

When the territory of Montana was created in 1864, the federal government granted the Northern Pacific Railroad approximately 13 million acres of land in Montana. This vast amount of land included every other section in a strip 80 miles wide along its line, plus lieu selection privileges within 10 miles of the outer limit of the original grant. This huge land grant led to the checkerboard ownership pattern still evident in the Swan Valley and other areas. Some 69,000 acres of NPRR sections lay within what is now known as the Bob Marshall Wilderness. The NPRR made lieu selections within the adjacent indemnity limits to make up for land already claimed for homesteads, mining, Native American reservations, and so on (later Congress authorized the railroad to acquire lands beyond even those boundaries). By 1927 the NPRR had sold over 35 million of the 39 million acres it had been granted, but it had not yet sold or traded the land within the Flathead National Forest (Conrad 1964:26; Merriam 1966:18; Schwinden 1950:90, 121; Cotroneo 1966:147).

In 1922, a party of NPRR and Forest Service representatives traveled together into the previously unexplored eastern slopes of the Mission Mountains. When the Mission Mountains Primitive Area was established in 1931, 30% of the land was still owned by the railroad. In the late 1940s and early 1950s the NPRR traded most of its land holdings at higher elevations inside the primitive area boundaries for Forest Service lands elsewhere in the Swan Valley. By 1963, all but 2,800 acres of NPRR lands in the Missions had been traded, and by the early 1970s all of the NPRR lands in the Missions had been exchanged (Wright 1966:16-17; FNF "Guide" 1980).

In general, the NPRR managed its lands to maximize profits for company stockholders. Some of the land was managed for recreation, however, including the leasing of summer home sites on Holland Creek (this program was started in the early 1960s) (Wright 1966:59-60).

Glacier National Park

By the early 1900s a schism had developed within the American conservation movement. Conservationists such as Gifford Pinchot favored the utilization of natural resources on forest reserves and the opening of national parks to grazing, timber harvest, and general development. Preservationists such as John Muir and George Bird Grinnell, on the other hand, favored maintaining national parks in a natural state, preserved for their beauty, recreation possibilities, and scientific potential (Buchholtz 1969:3).

On the local level, as early as 1906 the Inter Lake of Kalispell was warning its readers to keep an eye on the movement to create a national park out of a portion of the forest reserve and to "be ready to get in an emphatic protest" (Daily Inter Lake 7 September 1906). Some Kalispell residents and a few politicians did oppose the creation of Glacier National Park. Kalispell attorney Sidney Logan objected to the park proposal because of the anticipated regulations. He wrote Senator Carter:

While the name "National Park" may have an alluring sound to the observation car tourist, the words "public domain" ring sweeter to the ears of the average Montanan... [who] loves to commune with nature unhampered and unwatched. The sight of cotton bed sheet nailed to a tree and covered with regulations telling him what will happen [to] him if he does not toe the mark, is exceedingly obnoxious and detracts from his enjoyment of the scenery ("Protests" 1907).

But many would have agreed with Senator Dixon of Montana, who approved of creating Glacier National Park because it was "an area of about 1,400 square miles of mountains piled on top of each other...Nothing is taken from anyone" (quoted in Oppedahl 1976:48).

The act creating Glacier National Park in 1910 reflected this division. Timber harvests for revenue, the hunting of predators, existing homesteads, one-acre plots for private summer homes, railroads, and existing reclamation projects - all were allowed in the newly designated Park. The first superintendent's job was to convert the forest reserve into a park that was more accessible to the public (Buchholtz 1969:4).

Fremont N. Haines, supervisor of the Blackfeet National Forest, remained as acting superintendent of Glacier National Park until August 5, 1910. He and the first Park superintendent William Logan spent almost all their time dealing with the 1910 fires that burned through the Forests and Park that summer. The next year the Forest Service moved its offices from the Indian (Akokala) Creek Ranger Station, located within the new Park, to the west side of the river, where Blackfeet National Forest employees and various homesteaders built a new ranger station on Moran Creek (Buchholtz 1969:5; USDA FS "Early Days" 1976:140).

Waterton Lakes National Park was created just across the border in Canada in 1911 out of the Kootenai Lakes Forest Reserve. In 1932 the Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park was dedicated.

Glacier View and Other Proposed Dams

Since 1899 Congress has had the right to authorize the damming of navigable streams, primarily for flood control. In approximately 1920 the Regional Forester proposed several power sites along the Flathead River as part of a Forest Service effort to attract the pulp and paper industry to the area. The proposed dam sites were on the Flathead River near the confluence of the South Fork, on the North Fork not far north of the Forest Service boundary, at the outlet of Swan Lake, and at the outlet of Flathead Lake (Winters 1950:13; USDA FS "Possibilities" ca. 1920:10-11).

In 1942 a proposal to raise Flathead Lake by several feet to increase the capacity of the Polson power plant led to a storm of public protest. Preliminary surveys were then made of various dam sites in the North Fork. In the mid-1940s test drilling was carried on at Fool Hen Hill and at Glacier View Mountain. As early as 1943 the Army Corps of Engineers began talking about a proposed dam called the Glacier View Dam to be used for both flood control and power generation. The dam would have been located just north of the Big Creek Ranger Station on the North Fork of the Flathead River. The reservoir would have flooded thousands of acres of Glacier National Park and of the Flathead National Forest (see Figure 35) (Robinson & Bowers 1960:100; Buchholtz 1976a:71).

|

| Figure 35. Location of proposed Glacier View dam and reservoir (courtesy of Flathead National Forest, Columbia Falls). |

In 1948 the proposed Glacier View Dam received national attention as a result of public hearings in Kalispell. Most of the testimony was against the dam, including that of the National Park Service and major conservation groups. North Fork residents opposed being "drowned out," many people did not want to see so much of the Park flooded, and others talked about the destruction of wildlife habitat. Some people argued that reforestation of cut-over and burned areas would be a better way to help with flood control and that the reservoir would increase the problems of fire protection. Some Kalispell groups, however, supported the dam because of anticipated economic benefits. It was agreed to set the project aside until studies indicated that it was needed by the nation and that there were no feasible substitutes (Glacier National Park, "The Glacier View Dam Project" 1955:1; Atwood 1949:15-16, 18; "Proposed Glacier View Dam" 1948).

In 1949, the North Fork Ranger District of the Flathead National Forest was renamed the Glacier View Ranger District. This was due to the confusion caused by the existence of the similarly named North Fork Ranger Station in Glacier National Park, and to the local and national recognition of the name Glacier View due to the proposed Glacier View Dam (Fred Neitzling to Forest officers, 11 March 1949, GVRD).

After the public debate in 1948, the Army Corps continued to advocate other North Fork sites that would flood less Park land. The National Park Service built Camas Creek Road through the area to show its recreational intentions in the disputed area. In 1949 Senator Mike Mansfield tried to revive the Glacier View dam project, saying it "would not affect the beauty of the park in any way but would make it more beautiful by creating a large lake over ground that...has no scenic attraction" (Buchholtz 1976a:71; Oppedahl 1976:120).

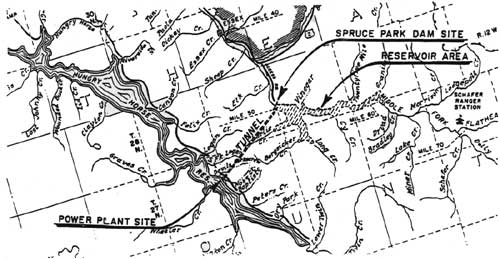

Two other proposed dam sites were the Smoky Range Dam, which would have been located five miles south of the Big Creek Ranger Station, and the Canyon Creek Dam, about 6 miles south of Big Creek, both on the North Fork of the Flathead River. The Spruce Park dam site was located about 6 miles upstream from the confluence of the Middle Fork and Bear Creek. Proposed in 1957, the Bureau of Reclamation planned to connect it via a transmountain tunnel to a generating plant on the bank of the Hungry Horse Reservoir near Hoke Creek (see Figure 36). The dam, if built, would have required the clearing of about 3,000 acres. By about 1960 the Spruce Park Dam was low priority, and it was never built (FNF, "Timber Management, Glacier View" 1959:23; Burk 1977:107; FNF "Timber Management, Coram" 1961:17).

|

| Figure 36. Location of proposed Spruce Park dam, reservoir, and tunnel (HHRD). (click on image for a PDF version) |

Hungry Horse Dam

The completion of the Hungry Horse Dam on the South Fork in 1953 - and the related completion of the Anaconda Aluminum Plant two years later - had significant impacts on the Flathead Valley. Proposals for a dam at that location had been discussed for several decades before it was actually built.

The power development possibilities in the South Fork were investigated as early as 1910, and the site for a dam on the South Fork 5 miles upstream from the mouth of the river had been selected by 1924. The final survey and report for the Hungry Horse Dam project was completed by the Army Corps of Engineers in approximately 1941. In 1944 Congress authorized the construction of the dam, and planning for the dam began at the end of 1945 under the direction of the Bureau of Reclamation. The stated purpose of the dam was stabilization of river flow for greater power development throughout the Columbia River Basin. The reservoir flooded approximately 22,500 acres of land, all of it on the Flathead National Forest (Jones 1924:96; USDA FS "A Study" 1948).

Logging the 37 square miles of reservoir yielded about 90 million board feet of saw timber, plus utility poles, pulp, railroad ties, and fuelwood in the flowage area. Contractors were required to remove all trees that were larger than 1" in diameter and 5' above the ground and to leave no stumps more than 2' high. To clear the flowage area, contractors experimented with five 8'-diameter steel balls supporting steel cables and pulled by pairs of diesel tractors. This "highball" clearing method, developed in 1949, snapped and uprooted trees as large as 4' in diameter. The method was not as successful as had been hoped, however, and eventually the logging contractors returned to standard methods. The trees that were felled during the clearing for the reservoir were skidded to a mill at the site, and some of the lumber was used in building houses for Bureau of Reclamation employees (USDA FS "A Study" 1948; Merriam 1966:67; Shaw 1967:136; "Contractors High-Ball" 1950:14-15; W. Elwood 1994; Kalispell News, 18 March 1948).

The Hungry Horse Dam, completed in November of 1953, is 564' high. It backs up water as far as 34 miles away, with a maximum depth of 500'. In addition to generating electricity, it regulates the flow of the South Fork and aids in flood control (Montana Conservation Council 1954:33-34). It also increases the production capacities of the Kerr and Thompson Falls power plants and others downstream on the Columbia River Basin system.

As mitigation for the flooding of Forest Service administrative sites, the Flathead National Forest requested that the Bureau of Reclamation replace the four work centers within the flowage area with two identical work centers (Betty Creek and Anna Creek), one on each side of the reservoir; reestablish pasture; relocate phone lines; replace Riverside Lookout and its communication facilities with a lookout on Firefighter Mountain; and replace the road along the South Fork River with a road on each side of the reservoir. After the dam was completed, the Forest Service obtained the Bureau of Reclamation buildings to use for administration and housing, including 13 dwellings, a dorm, a conference hail, a cement-testing lab, and the building that is now the Hungry Horse Ranger District office (USDA FS "A Study" 1948; Shaw 1967:137, 139).

The ACM decided to build an aluminum plant just outside of Columbia Fails in order to obtain favorable electric rates. The company obtained contracts for large blocks of power from the Bonneville Power Administration, and construction of the aluminum plant began in 1953. The plant converts alumina into primary aluminum by an electrolytic process in pot rooms (Springer 1976:51-52; Montana Conservation Council 1954:40). The aluminum plant employs hundreds of people and has had a major effect on settlement patterns and the economy of the upper Flathead Valley.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/flathead/history/chap6.htm Last Updated: 18-Jan-2010 |