|

Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960 |

|

FOREST RESERVES

Introduction

Public land policy in the United States can be divided into three periods: disposition (converting the land to private ownership and thus removing it from the public domain), reservation, and management. The disposition period lasted from approximately 1776 until 1891, when the Forest Reserve Act was passed. The public land was then reserved (withheld) until 1905, when the Forest Service took over the management of the forest reserves. From then until the present, national forest lands have been actively managed (Dana 1980:10).

The two forest reserves, portions of which later became the Flathead National Forest, were the Flathead Forest Reserve and the Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve. They were created in 1897 amidst much local protest. Forest rangers under the General Land Office worked in challenging conditions with little instructions and low financial rewards. Many of these rangers were men who already lived in the area and possessed the required skills needed for the varied outdoors work.

Forested Land on the Public Domain up to 1891

In the 1870s scientists were proclaiming dire warnings about a coming "timber famine "in America. The growing fear that the nation's white pine supply was being depleted raised public awareness of the dangers of passing public lands into private ownership as quickly as possible, which had been federal policy up to that time (Gates 1968:563).

Support for forest conservation arose in the late 1800s in response to the destruction of timber by fire and the wasteful timber harvesting practices of the day, combined with the growing belief that forests were important for the protection of watersheds and prevention of floods. Groups that supported the creation of forest reserves included preservationists seeking parks, sportsmen seeking game habitat protection, western farmers and urban dwellers seeking watershed protection, and professional foresters in the Department of Agriculture concerned about forest depletion from fire, insects, disease, and non-sustained-yield forestry practices (T. West 1992:3, 29). The views of Native Americans on the creation of forest reserves in northwestern Montana have not been identified, but their rights to use and occupy the land being considered for forest reserves were not discussed in the debates.

In 1875 the American Forestry Association was organized as a citizens' group to promote "forest conservation" and timber culture. The association supported the drive to obtain congressional authority to reserve as public forests those government-owned timberlands in the West that had not already passed into private ownership. The first technical forester in America was Dr. Bernhard E. Fernow, a Prussian who came to the United States in 1876. He served as chief of the Division of Forestry in the U. S. Department of Agriculture from 1886-1898. Fernow stressed principles of sustained-yield management that he had learned in Europe. Professional forestry education in the United Sates began with the opening of the College of Forestry at Cornell in 1898 and at Yale in 1900 (Winters 1950:2, 3, 7; Clepper 1971:21; Dana 1980:52-53). Until then, all professional foresters had been educated abroad.

Congress had forbidden the removal of timber from the public domain as early as 1831. By 1854 the GLO was given the responsibility of protecting the public domain but little funding to do so. Westerners who were determined to "tame the wilderness" considered the regulations unreasonable and foisted upon them by outsiders. In the 1800s many lumbermen bent and broke the timber trespass laws. Often they genuinely believed they were acting in the public interest, based on the prevalent doctrine of progress: they were, after all, turning resources into capital, opening new areas, and helping to found new communities (Steen 1976:6-7; Cox 1985:142).

The Timber and Stone Act of 1878 represented an attempt by the government to control wholesale timber cutting and quarrying on public lands while at the same time allowing people with particular needs, such as miners, access to timber. Each claimant could obtain up to 160 acres for $2.50 an acre. The land had to be unfit for cultivation and valuable chiefly for timber or stone. Miners, ranchers, and farmers could cut timber for improvements on their land but were not supposed to export or sell it. Before this act there had been no legal way for anyone to harvest timber. The act soon led to fraud, however. Corporations and wealthy individuals obtained timber fraudulently for large-scale logging operations or held land for speculation; some even hired gangs of men to make entries on behalf of others. It proved to be almost impossible to protect the public timber supply by this act because the few investigating agents faced hostile westerners, including the local press, politicians, and juries. In 1892 the act was amended to include Montana. Because of this act, 663,552 acres of Montana forest land passed into private ownership (mostly large lumber companies) (Dunham 1970:61; Hudson et al. ca. 1981:216; Gates 1968:550-551, 561; Toole 1968:357).

By 1891 the pineries of the upper midwestern states had largely disappeared, future exhaustion of the timber supply of the south was becoming apparent, and vast areas of land along the Pacific coast had been transferred to private individuals and corporations. At that time, according to forester (and later Forest Service Chief) Gifford Pinchot, the stealing of government resources was "a common and perfectly normal occupation, freely and openly pursued by the most respectable members of the community... The job was not to stop the ax, but to regulate its use" (Kinney 1917:244; Pinchot 1947:24, 29).

Creation of the Forest Reserves

The 1891 Forest Reserve Act authorized the President to establish forest reserves as part of a broader effort to revise the public land laws. President Harris created the first forest reserve, the Yellowstone, that year. The act had as its first purpose the protection of watersheds; it was only secondarily concerned with the maintenance of a permanent supply of timber (Pyne 1982:185). The 1891 legislation lacked provisions for the administration or protection of the forests from trespass and fire. Under the act, no timber could be cut, no forage grazed, no minerals mined, and no roads built in the forest reserves. The closing of the reserves to entry or utilization infuriated western stockmen, settlers, miners, and lumbermen.

As Gifford Pinchot stated in 1907, the forest reserves were created because forests of the West were being destroyed by fire and reckless cutting. The setting aside of the land was intended to "save the timber for the use of the people, and to hold the mountain forests as great sponges to give out steady flows of water for use in the fertile valleys below." Much of the early support for setting aside forest reserves came from western irrigators. Watershed protection would help them because forests absorbed rainfall, retarded stream run-off, increased ground-water levels, slowed snow melt, and lessened soil erosion (Pinchot 1907:7; Hays 1959:22-23).

When the forest reserves were first created, the boundaries were delineated without much on the-ground information, so agricultural land frequently was included and timbered land excluded. After 1900 money and manpower became available for field examinations, and many boundaries, including those in northwestern Montana, were subsequently adjusted (Pinchot 1907:8).

Since the 1870s it had been proposed to reserve lands at the headwaters of the Missouri and Columbia Rivers in order to control the quality and rate of flow of these rivers. In September of 1891, an Inter Lake article mentioned that the American Forestry Association had proposed a 6,106-square-mile forest reserve in the northern Rockies. General Land Office (GLO) special agent A. F. Leach examined the lands involved. The proposed boundary ran from midway between the 112th and 113th degrees of longitude in Choteau County, from there south to the head of Elk Creek in Lewis and Clark county, then northwest to the head of Flathead Lake, then directly north to the boundary line and back east to the starting point. The surveyor general of Montana, George Eaton, opposed the setting aside of this reserve, and the State Board of Land Commissioners also protested the request (Huffman 1977:253; Inter Lake, 27 September, 19 October, and 4 December 1891).

A. F. Leach himself commented to a reporter that "he has as yet to find a single man who is in sympathy with the scheme, and that every man with whom he has conversed is bitterly opposed to any such reserve," particularly because it would injure miners and prospectors (Inter Lake, 4 December 1891). The Surveyor General of Montana submitted a stronger comment in November of 1891:

As for the contingently suggested idea of extending this Reservation westerly to the Kootenai river, with the consequent annihilation of all prospects of material advancement of Northern Missoula county, I can only say that I regard such suggestions as emanating from the brain of a mad man" ("Montanans Oppose It!", Inter Lake 27 November 1891).

Plans for a forest reserve in the northern Rockies were temporarily shelved.

On February 22, 1897, just days before he left office, President Cleveland established 13 new forest reserves in the west, including the first four in Region One: Flathead, Lewis & Clarke, Bitterroot, and Priest River. The creation of these 21 million acres of "Washington's Birthday reserves" was based on the recommendations of the Forest Commission. (In 1896 the National Academy of Sciences had appointed a National Forest Commission, which included Gifford Pinchot as a member, to present a plan for forest management.) The Commission also recommended creating an administrative agency to oversee the reserves, to create fire prevention programs, and to regulate grazing, mining, and timber harvesting (Huffman 1977:262; Steen 1976:31; Robinson 1975:7).

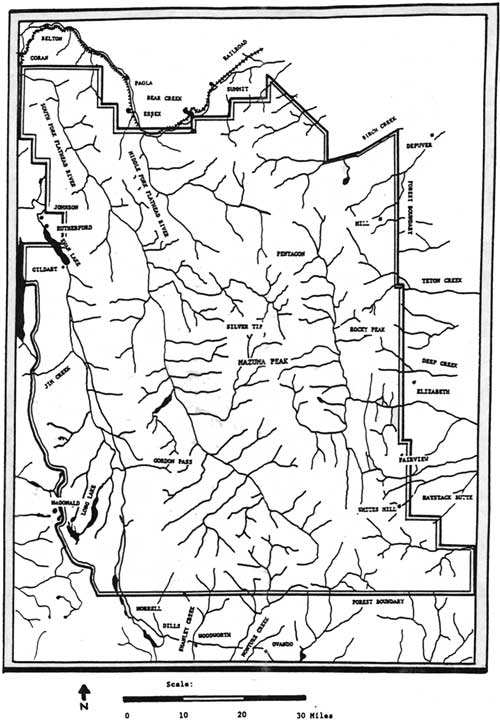

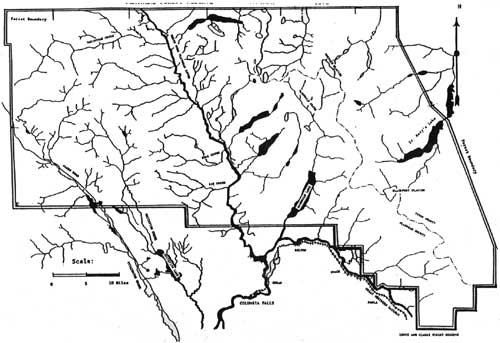

When established, the Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve covered 2,926,000 acres (see Figure 16). The Flathead Forest Reserve included 1,382,400 acres (see Figure 17) (Ayres "Lewis & Clarke" 1900:36; Pinchot 1947:108). Portions of the Flathead and the Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserves created in 1897 are now much of the land managed by the Flathead National Forest.

|

| Figure 16. Lewis & Clark Forest Reserve boundaries in 1898 (drawn by Todd Swan, based on map in Ayres "Lewis & Clarke" 1900). (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Figure 17. Flathead Forest Reserve boundaries in 1898 (drawn by Todd Swan, based on map in Ayres "Flathead" 1900). (click on image for a PDF version) |

The Flathead Forest Reserve included the land that is now Glacier National Park until the Park was created in 1910.

The Forest Reserve Act of 1897 (also called the Organic Act) directed the Secretary of the Interior to protect the forest reserves against fire and depredations (timber trespasses, for example) and authorized him to make regulations for the administration of the reserves. This act represented a compromise between western interests and conservationists. It suspended the actual withdrawal of the "Washington's Birthday reserves" until March 1, 1898. The Pettigrew Amendment, approved by the President in June 1897, allowed the exclusion of agricultural or mineral lands located within the reserves, permitted free timber and stone to settlers, authorized the sale of mature or dead timber at or above appraised value, and retained the clause for lieu land. By the latter provision the government lost millions of acres of its best lands as railroads, private concerns, and individuals exchanged their worthless land within the forest reserves for valuable land elsewhere. Individuals and corporations abused this act freely, even relinquishing land that they had already cut over in exchange for forested acreage (Clepper 1971:27; Robinson 1975:7; Kerlee 1962: 14-15; Steen 1976:35-36; Ise 1920:141-142, 176).

The 1897 Forest Reserve Act, or the Pettigrew Amendment, formed the basis of federal forest reserve management until it was supplemented in 1960 by the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act. The 1897 act defined the purposes of the forest reserves as follows: to "preserve and protect the forest within the reservation... for the purpose of securing favorable conditions of water flows... [and] to furnish a continuous supply of timber for the use and necessities of the people of the United States." This reflected a compromise between preservation (non-use) and conservation (use), and a number of the amendments listed above greatly reduced the local antagonism towards forest reserves. The GLO administered the reserves in a custodial manner through the regulation of use and occupancy (Dana 1980:62; Steen 1976:36).

One of the proponents of a forest reserve in the Flathead area was well-known preservationist John Muir. He accompanied Gifford Pinchot on his trip to the Flathead Valley area for the National Forest Commission in the late 1890s (Steen 1976:49). In 1898, shortly after the creation of the forest reserve, Muir wrote:

if you are business-tangled, and so burdened with duty that only weeks can be got out of the heavy-laden year, then go to the Flathead Reserve; for it is easily and quickly reached by the Great Northern Railway. Get off the track at Belton Station [West Glacier], and in a few minutes you will find yourself in the midst of what you are sure to say is the best care killing scenery on the continent...Give a month at least to this precious reserve... [it] will lengthen your life (Muir 1898:22-23).

Gifford Pinchot himself remembered the area as the place where he first learned how to throw the diamond hitch (a method of tying down loads on pack animals) and where he successfully hunted deer, bear, elk, goat, and mountain sheep. "This region holds some of the pleasantest memories of my life," he later maintained ("Memorial Dedicated" 1931:214-218). Commenting on an 1896 trip he and Jack Monroe and his bear dogs took up the Swan Valley, from which trip the Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve was created, Pinchot wrote:

To me it was a fairy land, in spite of the mosquitoes, which were so bad that I wore gloves, a flour sack across my shoulders, and a handkerchief over my ears and neck. The only chance we had to sleep was when the cold of the short July nights moderated their zeal. But the country more than made up for everything....It was a gorgeous trip - the best I ever made on foot (Pinchot 1947:98-99).

Soon after the Montana forest reserves were created in 1897, the state legislature passed a resolution requesting that the order be rescinded, declaring that the forest reserves "would seriously cripple and retard [Montana's] development." President Cleveland had established the reserves in 1897 without any notice to those affected. Many western congressmen became "permanent enemies of the reserves." Many county governments were also resistant to the reserves because they reduced future tax income (Schutza 1975:59; Kerlee 1962:14, 27). In 1897 Montana forestry professor George Ahern made the revealing comment that "Two companies dominate the state, and all opposition to the reserves is inspired by these companies...The milling companies know that their logging methods will receive some supervision, and they do not want any supervision" (Helena Independent, 3 May 1897, SC 1533, MHS).

In the late 1890s Ahern showed slides on the effects of deforestation throughout the state. He served as a local enthusiast for national forest reserve policy (Rakestraw 1959:40, 43). A few weeks after the Montana forest reserves were created in 1897, Ahern wrote a letter promoting this act and stated that "it would be wiser to give the timber away than to let this indiscriminate slaughter continue." He had outlined the Lewis & Clarke forest reserve three years earlier, mapping "a reserve that did away with every reasonable objection. No agricultural land was included; no mines (one exception); the timber land is not an immediate necessity; there are no settlers to be disturbed" (Helena Independent, 19 & 23 March 1897, SC 1533, MHS).

Another published supporter of the Montana forest reserves was Mrs. T. J. Walsh, although she was somewhat misinformed as to their purposes. In 1901 she wrote the following about her visit to Lake McDonald in the Flathead Forest Reserve:

It is a matter of sincere congratulation that this whole region...is included within the Flathead Forest Reserve, ensuring to this and future generations its preservation in native beauty and sublimity...the correlative duty devolves upon [the government] of constructing roads and trails to the many points of interest for the tourist and scientists, that are hidden in these solitudes. They could be constructed and maintained under the supervision of the forest rangers, at trifling cost" (Walsh 1901:330).

Before President Theodore Roosevelt left office in 1907, he had tripled the total area of forest reserves in the country. In 1907 the authority of the president to create new forest reserves in Montana and other states was revoked, not to be reinstated for Montana until 1939 (R. Robbins 1976:349; G. Robinson 1975:9).

GLO Administration of the Forest Reserves, 1898-1905

The GLO administered the forest reserves from 1897 until 1905, when the Forest Service was created. The GLO was staffed not with foresters but with politically oriented men who were influenced by lumbermen, timber speculators, railroad men, and stockmen. In 1897 the forest reserves in the country totalled only a little over 30 million acres (by 1905 the acreage had increased to almost 86 million). The reserved land was mostly mountainous areas in the Pacific Coast states and in the central and northern Rockies. The most prevalent use at that time was grazing, not timber harvest (Gates 1968:571, 573; Clary 1986:3).

Forest supervisors did not receive much financial reward for their labors. In these early years, they were paid $1,000 per year and had to furnish their own horses, subsistence, and camp equipment out of that amount. They apparently worked seasonally. On April 2, 1901, Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve supervisor Gust Moser wrote to his superior, J. B. Collins, "Have you heard anything about season's work - I am getting rather discouraged - With the most rigid economy I find myself going in debt each month from $25 to $35 and it will take about all summer on a Supervisor salary to get even with the world." In 1906, supervisor Page S. Bunker also reported that he was unable to pay his expenses out of his salary even "with utmost economy" (Shaw 1967:15; 2 April 1901, Lewis & Clarke pressbook, FNF CR; Elers Koch, 28 November 1906, "Report of the Section of Inspection," entry 7, box 4, RG 95, NA).

Forest supervisors in 1899 were required to be familiar with all the conditions in their forests, especially forest fires. They had to make sure that cloth notices of the forest fire act of 1897 were posted and that people within the reserves were warned about being careless with campfires. Supervisors also had to make sure the rangers did their assigned tasks. They had to fill out weekly and monthly work reports, plus detailed reports on any forest fires and associated expenses, including the probable market value of the timber burned and the effects on the forest cover and water supply. Rangers, the field men, were required to patrol their districts, extinguish fires, report all fires, and make monthly reports of their daily work (Hermann 1899:196, 199).

The early rangers were hampered by their lack of funding and authority and by the fact that the forest reserves were not adequately surveyed for several years. Although the rangers wore round nickel badges to show their authority, until 1905 they had no power of arrest without a court warrant (Pyne 1982:232).

In the early GLO days, very few rangers worked on the Forests. In mid-September, 1901, for example, there were 13 rangers on the Flathead Forest Reserve, 16 on the Lewis & Clarke, 6 on the Bitter Root, and 1 on the Gallatin. Even so, these rangers were a new and often unwelcome presence in the woods. Clarence B. Swim, a ranger on the Yellowstone Forest Reserve in Wyoming, recalled a westerner commenting in 1904, "Are you a forest ranger? God, rangers are getting thicker than fiddlers in hell!" (J. B. Collins to F. N. Haines, 17 September 1901, RG 95, NA; USDA FS "Early Days" 1944:185).

The bureaucracy - in the form of written reports - was fairly extensive even in the early years. In 1901 Supervisor Moser attempted to interpret GLO requirements to ranger Ernest Bond of Holt: "When you state in your report that it rains or storms, you must state the duration and extent of same, to say it 'rained' won't do, the Department wants to know how hard it rained etc." But on the same day Moser wrote another letter to his superior complaining: "I am astonished, at the same time it seems that the Department thinks we are so endowed, that in a period of 5 months in the year, we can become thoroughly acquainted with a wild and undeveloped country and sit at our desks and make reports." Rangers were also required to report where they were on Sundays, even though they were not expected to work for the government on that day (J. B. Collins to F. N. Haines, 17 September 1901, entry 13, box 5, RG 95, NA; 12 June 1901, Lewis & Clarke pressbook, FNF CR).

Adding to the difficulties, communications between rangers and the forest supervisor were often delayed (telephones and radios were not yet available). For example, on the Lewis & Clarke reserve in 1901 it often took 10-14 days for a letter to make a round trip to the rangers. It could be very complicated and time-consuming to obtain needed supplies, too. For example, when Gust Moser needed four cross-cut saws he had to request them from Superintendent J. B. Collins in Missoula, who received authorization for the purchase from the GLO Commissioner in Washington, D. C. Collins then purchased the saws and had them shipped to Ovando, and Moser had to advise Collins of their receipt (24 May 1901, Lewis & Clarke pressbook, FNF CR; J. B. Collins to Gust Moser, entry 13, box 2, RG 95, NA).

Early forest rangers were given little or no training or instructions. The first U. S. forest ranger, Bill Kreutzer, was hired in Denver in August of 1898. He was instructed to "take horses and ride as fast as the Almighty will let you and get control of the forest fire situation on as much of the mountain country as possible. And as to what you should do first, well, just get up there as soon as possible and put [the fires] out" ("Wiliam R. Kreutzer" 1947:765).

Gifford Pinchot worked hard for the transfer of responsibility from the Department of Interior under the GLO to the Department of Agriculture. In 1898 he became the Chief of the Division of Forestry, and after 1900 he served as the head of the new Bureau of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture (Hays 1959:29). Pinchot changed the name of the Bureau of Forestry to the Forest Service in 1905 to show that the administration was a service, and he changed the name of the forest reserves to national forests in 1907 to show that land was not actually withdrawn.

Yet in 1905 it was difficult for Pinchot to hire foresters to work for the Bureau of Forestry. In that year, only about 75 foresters had graduated from a college offering professional forestry training. When the forest reserves came under his supervision, Pinchot made the young foresters who had been doing boundary surveys in 1903 and 1904 into inspectors; their job was to weed out the "worst incompetents" among the political appointees and replace them with new men. According to Elers Koch, one of the inspectors in Region One, "It was like a fresh wind blowing through an old, corrupt, and hide-bound organization. We went to it with the enthusiasm of youth" (Randall 1967:28; Elers Koch, 11 June 1940 memo, 1680 History, "Region One History and History of the Forest Service," RO; Koch ca. 1940).

Gifford Pinchot helped shape the conservation movement of the late 1890s and early 1900s. Professionals set the tone, and the focus was on rational planning to promote the efficient development and use of all natural resources. The emphasis on saving trees from destruction shifted to sustained-yield forest management over the long term. Both private and public forest leaders promoted a stable and permanent lumber industry (Hays 1959:28-29, 35).

In 1903 Pinchot declared, "The object of our forest policy is not to preserve the forests because they are beautiful...or because they are refuges for the wild creatures of the wilderness...but...the making of prosperous homes" (Hays 1959:42). In 1905 Pinchot wrote a letter (signed by the Secretary of Agriculture) that stated the objectives of forest reserve administration as follows:

it must be clearly borne in mind that all land is to be devoted to its most productive use for the permanent good of the whole people and not for the temporary benefit of individuals or companies. All the resources of forest reserves are for use, and this use must be brought about in a thoroughly prompt and businesslike manner...where conflicting interests must be reconciled, the question will always be decided from the standpoint of the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run (1 February 1905 letter, 1680 "Region One History and History of the Forest Service," RO).

In 1910 Gifford Pinchot was replaced by Henry Graves because of a political controversy at the national level, but Pinchot's ideas continued to guide Forest Service management of the national forests for decades to come.

Forest Supervisors and Rangers on the Flathead and Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserves, 1898-1905

The director of the GLO appointed J. B. Collins as the superintendent (with headquarters in Missoula) of the new forest reserves in Montana and Idaho. Major F. A. Fenn replaced him in 1903. Gust Moser was the first supervisor of the Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve (out of Ovando), and William J. Brennen the first supervisor of the Flathead Forest Reserve (out of Kalispell) (see Figure 18). In June of 1899, 9 rangers were assigned to the latter and 6 to the former. In July, 9 additional rangers were assigned for the state (Baker et al. 1993:46-47; Hermann 1899:199).

| Flathead National Forest | Blackfeet National Forest | |||

| 1898-1903 | Gust Moser | 1898-1903 | William J. Brennen | |

| 1904-1905 | Adelbert M. Bliss | 1904-1910 | Fremont N. Haines | |

| 1905-1913 | Page S. Bunker | 1911 | John F. Preston | |

| 1913-1914 | F. A. Fenin, Acting | 1911-1919 | Robert P. McLaughlin | |

| 1914-1915 | Donald Bruce | 1920-1921 | E. H. Myrick | |

| 1916-1919 | Joseph D. Warner | 1922-1924 | Leslie F. Vinal | |

| 1920-1922 | Kenneth Wolfe | 1925-1927 | James E. Ryan | |

| 1923-1930 | Lloyd G. Hornby | 1928-1932 | William Nagel | |

| 1931-1934 | Kenneth Wolfe | 1933 | Ralph Space, Acting | |

| 1935-1945 | James C. Urquhart | |||

| 1945-1962 | Fred J. Neitzling | |||

| 1962-1971 | Joseph M. Pomajevich | |||

| 1971-1977 | Edsel L. Corpe | |||

| 1977-1984 | John L. Emerson | |||

| 1984-1990 | Edgar B. Brannon, Jr. | |||

| 1990- | Joel Holtrop | |||

| Figure 18. Supervisors of Flathead and Blackfeet National Forests, 1898 to present. The two Forests were combined under the name of the former in 1933 (17 April 1958 memo, FNF - FS Personnel, RO; Shaw 1967:31; FNF records). |

Binger Hermann served as Chief of the GLO in the late 1890s, and he saddled the Division of Forestry with many inefficient political appointees. During this period (1898-1905), "Politicians considered the position of forest supervisor as a patronage plum...and bitterly criticized the General Land Office when it selected trained men for the post" (Kerlee 1962:16; Hays 1959:38).

Not a man to mince words, Pinchot described the GLO's field force on the forest reserves as "enough to make angels weep," noting that the political appointees were full of "human rubbish" (Pinchot 1947:167). In defense of the GLO, however, at the time the reserves were created a pool of men technically and administratively trained to manage the public forest reserves did not yet exist.

Gust Moser, the first supervisor of the Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve, had close political ties to Montana lumber company interests. He had previously served as secretary for the Montana Improvement Company, a large early lumber company in Montana associated with the Anaconda Mining Company (ACM). In 1895 powerful lumberman A. B. Hammond, with the help of Northern Pacific Railroad officials, tried to have Moser appointed the federal Mineral Land Selector so he could serve their interests (Butcher 1967:76-77). It is likely that Moser's appointment as supervisor of the Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve had political implications.

Gust Moser was one of the GLO appointees who was replaced because of incompetence. According to inspector Koch:

It is alleged that he [Moser] and his wife used to meet the rangers coming in for their monthly paychecks and mail, and that her wiles and other attractions, together with Gus' superior skill at poker, usually resulted in separating the rangers from most of their pay (USDA FS "Early Days" 1944:101)

In 1904 the GLO commissioner agreed with Koch's negative evaluation of Moser, recommending that he be dismissed. The Commissioner stated that Moser was "an habitual drunkard; that he indulges in prolonged seasons of drunken and disreputable conduct and refuses to satisfy his honest financial obligations, and that he had accepted compensation to which he was not entitled to for official favors; that he has shown favoritism to some of the forest rangers serving under him, to the detriment of the service, and knowingly approved false service reports submitted" (W.A. Richards to Secretary of Interior, 16 April 1904, entry 17, box 1, RG 95, NA).

Adelbert M. Bliss, Moser's successor, according to Koch, was "a nice old man, but quite incompetent, and his only excursions to the forest were drives in a buckboard over the only road in the reserve, to Holland Lake." Bliss had attended law school, served as a clerk in various government agencies, and had been a miner. His appointment was recommended by Senators Joseph Dixon, Thomas Carter, and others. His political connections were not strong enough for him to keep his job when the Forest Service took over, however; Bliss was removed in 1905 and his head ranger, Page Bunker, was made supervisor (31 May 1904, entry 17, box 1, RG 95, NA; Koch ca. 1940).

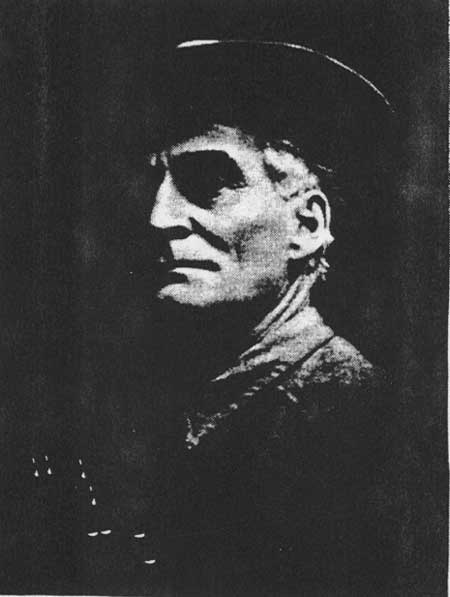

The first supervisor of the Flathead Forest Reserve, William J. Brennen, was considered "one of the most picturesque and best known men in public life in the state," and he also reportedly had close ties to the ACM (see Figure 19). A native of Watertown, New York, he worked for the Northern Pacific Railroad, coming to Montana in the early 1880s. In 1889 he opened a law office in Helena, but he moved to Kalispell in 1891. He was nicknamed "Tin Plate Bill" in 1896 because of his support of the McKinley tariff measure. President McKinley appointed him supervisor of the Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve (North) in 1898, to receive $5 per day and $1.50 for subsistence. Brennen had useful political connections; he counted as friends Theodore Roosevelt, President McKinley, and Senator Thomas H. Carter of Montana. Brennen resigned as supervisor in the early 1900s, although he later served as a state forester from Flathead County. From 1904 until 1908 he was a state senator from the Flathead, and in 1913 he returned to law practice in Kalispell (Stout 1921: III, 822-23; "Brennen's Plum," Flathead Herald-Journal, 21 July 1898; "W. J. Brennen Pioneer of State Dead," Flathead Monitor, March 15, 1928:1; "Senator W. J. Brennen Crosses Great Divide," Kalispell Times, 15 March, 1928; Ingalls ca. 1945).

|

| Figure 19. William J. Brennen, first supervisor of the Blackfeet National Forest (Stout 1921). |

Fremont N. Haines replaced Brennen in 1901, after a senator offered Haines the choice of working as a postmaster in the East or as a forest supervisor in Montana. Early ranger Joe Eastland commented that Haines at first "would have got lost in a big orchard." But, he worked hard and was well liked. Haines resigned in 1910 and settled with his family in Kila (O. Johnson 1954:12-14; Kalispell Bee 25 September 1901:3; Kalispell Journal 17 November 1910; Flathead Monitor 7 July 1938).

The early rangers were usually western men familiar with the outdoors. Often they had worked on ranches, been miners, worked in a lumber camp, or served in a war (particularly the recent Spanish-American War). Rangers under the GLO did not have to undergo a field test before being hired, as they did after 1905. The multitude of difficulties facing early rangers, no matter their experience, are described eloquently in this letter Belton (West Glacier) ranger George R. Rhodes wrote to supervisor A. M. Bliss in Ovando in 1904:

I have no Manual of Instructions for Rangers neither have I a Badge and I would be very thankful to you to Forward them to me as it will save a good lot of dispute that may arise from various sources in the Line of duty which I have to Perform (17 July 1904, FNF Class).

One Region One employee described his job in 1899 as follows. He said, "No equipment was furnished in the early days except a small amount of letterheads and a few franked envelopes...As we did not receive any, or but few, instructions, we did about as we pleased." He was told to patrol his district and familiarize himself with the topography of the country. In 1900 he and his coworkers began to retrace and cut out the down timber blocking the old Native American trails, then locate and mark the forest boundaries. They also started administering the free use of timber and grazing and prosecuting timber and grazing trespassers. Distinguishing the valid timber claims, established before the forest reserves were designated, from the invalid claims "made much unpleasant work" (Than Wilkerson, "Some of the Things Done and Conditions Under Which They Were Accomplished," 1680 History - Region One History and History of the FS, RO).

The rangers often met with local hostility since they had to sell the forest reserve idea to a suspicious public. The first ranger in the North Fork had a rough start, according to homesteader Eva Beebe. "They didn't want rangers up there," she said, so some of the homesteaders challenged him while hiding behind trees and forced him to drop his gun. Ironically, one of those men may have been Chaunce Beebe, who by 1917 was working as a ranger in the National Park Service (Beebe 1974).

One ranger, Jasper B. Seeley, was considered "a hard and tough man with a good sense of justice, but inclined to enforce regulations up to the hilt." One time he caught a man in the act of setting a forest fire. He arrested him and brought him to Ovando. When Supervisor Moser proved unwilling to bring the case to trial, Seeley started back with his prisoner. On the way he decided that "if the law would not act he would see that justice was done himself, stopped the horses, jerked the man off his saddle, and proceeded to half flay him with a black snake whip he carried" (Koch ca. 1940).

Some of these original Flathead rangers were personal friends of Teddy Roosevelt's. In 1900 President Roosevelt appointed Fred Herrig to patrol the country drained by the North Fork; he was stationed in the Indian (Akokala) Creek area. Herrig served as ranger of the Fortine District from 1901 until 1919. When he retired from the Forest Service in 1925, he had served at one station longer than any other man in the Forest Service up to that time. Herrig was originally from Europe; he came to the United States in 1875 when 15. For about five years, Herrig worked for Teddy Roosevelt at his ranch near Medora, North Dakota, and he served as Roosevelt's orderly in the Spanish-American War (Robinson & Bowers 1960:51; M. J. White ca. 1990; O. Johnson 1950:262).

According to the state forester in the area, Herrig "would do what he pleased, when he pleased, as he pleased, but there had to be plenty of Schnapps around to keep him going." Many stories are told about this colorful ranger. Herrig patrolled his domain on a black saddle horse accompanied by a Russian wolf hound. He wore silver spurs, his horse sported a silver-studded bridle and martingale, he carried a rifle in his saddle scabbard, and he wore a .38 revolver given him by Roosevelt (Cusick 1986:41; Yenne 1983:13).

In 1900, according to ranger Joe Eastland, rangers would do most of their work on foot, carrying their food and tools. Their tools included their badge, a marking axe, a notebook, a pencil, and a book of regulations. "And there was no use to lay off during bad weather, as the grub would play out." Also on the subject of food, ranger Frank Liebig in 1900 commented that while in the Lake McDonald area, "Bear meat was my main diet, as I had to declare war on these animals as they broke into my camps very often and destroyed my grub" (O. Johnson 1950:260; L. Wilson 1986).

According to the 1899 log books of Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve rangers, their time was primarily occupied with travelling, cutting timber from trails and roads, patrolling, posting fire warnings, clearing and piling brush and tree tops, and other similar activities. They generally worked from 8 a.m. to 6 or 7 p.m., did not take Sundays off, and came "out" once a month to report to the forest supervisor. For example, on June 12, 1899, Thomas Danahar [sic] wrote, "went to White River 12 miles down the South Fork of Flathead worked on trails." The next day he recorded, "Came back, met Indians they were camped opposite Gordon Cr. six of them, came up to the mouth of N. Fork of S. Fork distance 12 miles." Danaher had a ranch in the area now known as Danaher Basin. In 1904 Forest Superintendent F. A. Fenn recommended that Danaher be dismissed because he "occupied his time attending to personal affairs when he should have been performing the duties connected with his position as forest ranger." Perhaps ranch work kept him from his ranger duties (1899 log book, FNF CR; 19 May 1904, entry 17, box 1, RG 95, NA).

Some of the jobs assigned to early rangers were unusual, such as when the forest supervisor instructed Belton ranger George Rhodes in 1905 to monitor the amount of liquor sold by E. E. Dow in his Belton business. Two weeks later Rhodes was told to walk 8 miles to and from work each day in order to work on making the old railroad tote road passable, "even though snow will hinder the work" (14 January 1905, "Rangers 1-1-05 to 6-30-05" pressbook, FNF CR; 24 January 1905, "Rangers 1-1-05 to 6-30-05" pressbook, FNF CR).

Two of the early rangers on the Flathead Forest Reserve told the same amusing (and probably exaggerated) story about their supervisors' lack of comprehension of their daily work. Frank Liebig and W. H. Daugs each claimed that the Washington Office sent him a leaf rake to clean the forest floor and a leather bucket for carrying water to put out fires (Myrick 1929:2).

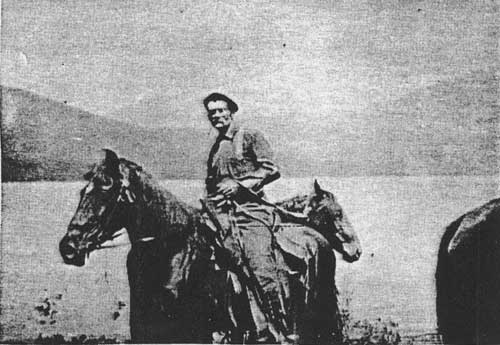

Frank Liebig moved to the Flathead area after working as a foreman on a cattle ranch in eastern Montana (see Figure 20). Educated in forestry in Germany, he left Europe to escape military service. In 1900 he was hired to survey oil claims in the Kintla Lake area for a Butte company. He then took up oil claims on his own in the Belly River drainage. In early spring of 1902, F. N. Haines offered him a job as forest ranger for $60 a month, if he furnished his own horses and boarded himself. Liebig took the job because he was offered the chance of a promotion. He was assigned a half a million acres on which to build trails and to patrol for fires, timber thieves, fraudulent miners, poachers, squatters, and game violators. That first year he had only two men to help him during the fire season. Haines gave him a double-bitted axe, a one-man crosscut saw, and a box of ammunition, and told him, "go to it, and good luck." Liebig covered the area from Belton north to Canada, including the land east of Lake McDonald all the way to the Blackfeet Indian Reservation. He worked in that area until the Park was designated in 1910, then continued to work for the Flathead National Forest until he retired in 1935. Liebig was also well-known for his skill as a taxidermist (many of his specimens are now in the Glacier National Park collection) (USDA FS "Early Days" 1944:129-130; Flathead County Superintendent 1956:14; "Winston and Liebig Retire" 1935:1; Vaught Papers 1/L).

|

| Figure 20. Frank Liebig standing on rock cairn at Swiftcurrent Pass, Lewis & Clarke Forest Reserve (North), 1906 (now part of Glacier National Park) (courtesy of Glacier National Park, West Glacier). |

Many of the early rangers were homesteaders or squatters on land within the reserve. One example was Frank Geduhn, who lived at the head of Lake McDonald (see Figure 21). In 1896 he wrote," I have been here six years, working up trade with summer tourists, when there were any; trapping for marten and other furs in the winter. It has been a continual fight for a bare existence; but loving these romantic surroundings and hoping for better times, I keep battling on." Geduhn's "battle" was aided by an appointment as ranger of the North Fork and Camas Creek areas in 1899 (Buchholtz 1976a:40-41; L. C. Hoffius to Vaught, 126 June 1899, Vaught Papers 4/C).

|

| Figure 21. Frank Geduhn at foot of Logging Lake, ca. 1907 (courtesy of Glacier National Park, West Glacier). |

Geduhn was originally from Germany and had been trained in forestry there. He lived approximately five years in British Guinea before coming to the Flathead Valley in 1894. He developed a "cabin camp" for tourists at the head of Lake McDonald, and he worked off and on for the Forest Service in that area. His supervisor described him as "deeply interested in his work" and mentioned that he had been experimenting with transplanting different trees at the head of Lake McDonald (J. B. Collins to GLO Commissioner, 20 August 1901, entry 13, box 5, RG 95, NA; Harrington, ca. 1957:38). According to a woman whose family bought land from Geduhn:

I cannot speak too enthusiastically of the utter devotion and loving care with which these early Forest Rangers, first Frank Geduhn, then Frank Liebig, guarded their territory...Each morning at daybreak Mr. Geduhn would start forth on his old black horse, his little dog trotting beside, with an axe and a saw, a little package of food and a blanket roll if, on the longer trips he would have to stay out overnight...he kept the trails in perfect condition with never a downed tree to interfere with the visitor's progress. Yet, in spite of his strenuous days, he was always ready to join the guests of his camp at the campfire where he would keep everyone entertained for hours with his tales of adventure. Or on rainy nights he would get out his old fiddle and play and call for square dances in which even the children joined (Harrington ca. 1957:27).

Other early Flathead rangers were perhaps not the best representatives of the federal government available. One of these was "Slippery Bill" Morrison, who had come west as a brakeman on a GNRR construction train, quoted Shakespeare freely, and had a "tongue like a two-edged sword." Morrison was appointed forest ranger in the early 1900s, and at the same time he ran a saloon at Summit that catered to railroad passengers and featured "gambling and other accessories on the side" (Johns 1943:V, 6; Atkinson 1985:15). According to forest ranger E. A. Woods:

Slippery Bill told me how he would stand in the door of the saloon, gaze at the distant landscape, return to the shelf where he kept the Government records, and write in his official diary, 'Looking over the Forest.' One of his contentions was that a good healthy porcupine could destroy more timber than a Forest ranger could save (USDA FS "Early Days" 1944:213).

In 1906 inspector Elers Koch discussed the pros and cons of John Sullivan, assistant ranger at Spotted Bear. Koch described John Sullivan, or 'The Bull of the Woods,' as an:

ex-prizefighter, ex-lumberjack, [who] is an ignorant, illiterate, ill-tempered native of the state of Maine. On account of his temper he is a difficult man for some of the rangers to get along with, and is somewhat addicted to going on a spree occasionally, though he has been much better in that respect in the past year. In spite of all these bad qualities he is an excellent man for a certain class of work on this reserve. He possesses almost a genius for laying out trails, and a bad grade or a poorly cut out piece of trail will never let him rest easy. He is an excellent axeman, and a good man at cabin construction. He is an experienced woodsman, and will make his way alone with his pack horses into the roughest kind of a country... While his illiteracy will prevent his ever rising above the grade of assistant ranger, he is decidedly a man worth keeping for work on this particular reserve, though he would be worse than useless on a reserve like the Big Belt (Elers Koch, 28 November 1906," Report of the Section of Inspection," entry 7, box 4, RG 95, NA).

Another early ranger was Albert Reynolds, appointed in 1901 at the age of 53. He was stationed near the foot of Lake McDonald; he had retired from supervising the Butte & Montana lumber mill operations near Kalispell to escape the "nervous strain" of that work. Like many woodsmen of the time, he seldom wore a coat in the woods; for warmth, he relied on physical exertion. If caught out overnight in the woods without shelter, he would build a fire and sleep beside it (Buchholtz 1985:50; O'Neil 1955:71).

Joe Eastland started work in 1900 for $60 a month. He checked mining claims, helped cut a boundary line along the west edge of the reserve, and constructed trails (including a 46-mile trail across the Whitefish Divide at Grave Creek). Eastland reminisced:

Well, in those days we worked out in all kinds of weather, winter and summer, long hours and short pay, and almost no equipment. But the country was fresh and unspoiled, and resting by the campfire was good enough after a hard day. We weren't served any fancy store food - but what else could equal the blue grouse and dumplings we used to have so often, or a frying pan of fresh trout, or a venison steak broiled over the open coals. We lived pretty high at that (O. Johnson 1954:12-14).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/flathead/history/chap5.htm Last Updated: 18-Jan-2010 |